* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Birds of Manitoba

Date of first publication: 1891

Author: Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946)

Date first posted: Sep. 1, 2017

Date last updated: Sep. 1, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170903

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION.

UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM.

THE BIRDS OF MANITOBA.

BY

ERNEST E. THOMPSON, of Toronto, Canada,

Associate Member American Ornithologists’ Union, etc.

From the Proceedings of the United States National Museum, Vol. XIII, pages 457-643, with plate XXXVIII.

[No. 841.]

WASHINGTON:

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE.

1891.

BY

Ernest E. Thompson, of Toronto, Canada,

Associate Member American Ornithologists’ Union, etc.

(With plate xxxviii.)

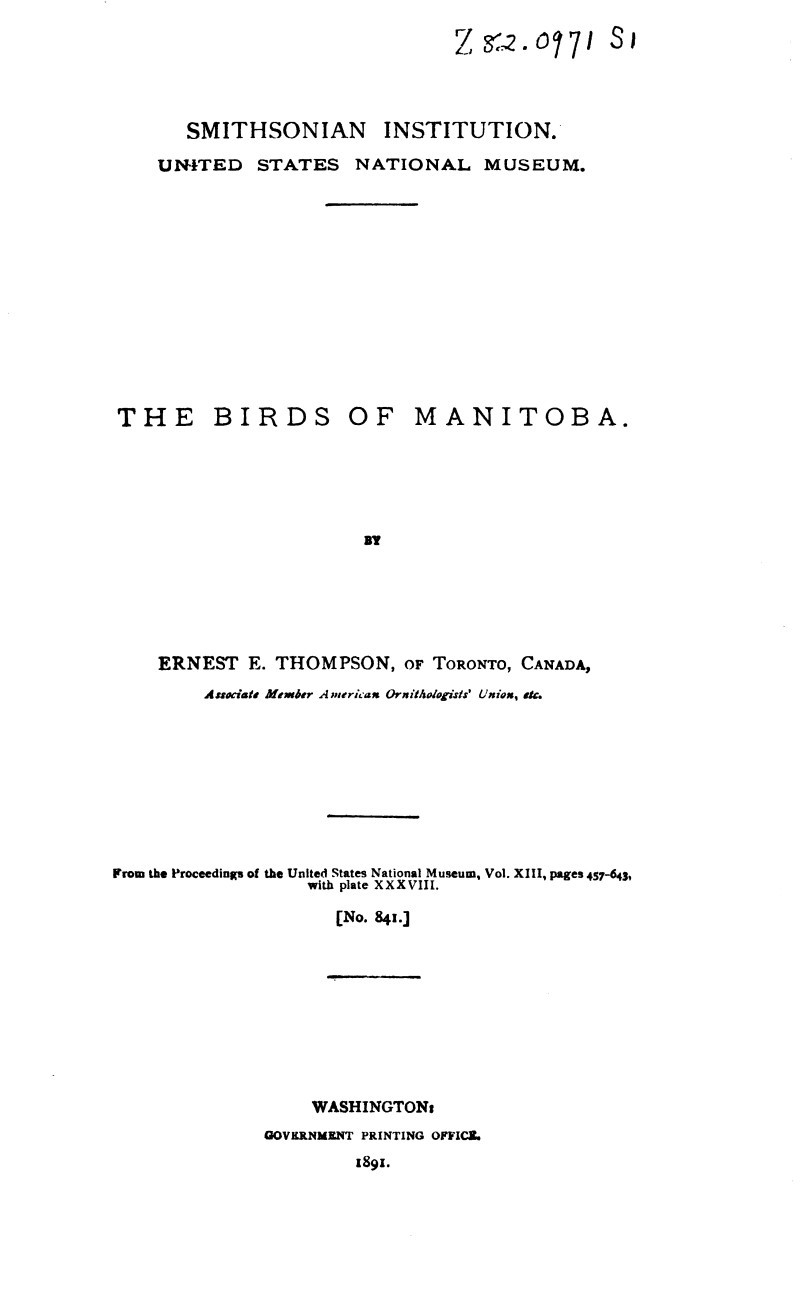

In treating of the birds of this region it seemed most convenient to make the political boundaries of the province, those also of the district included, though this is scarcely defensible from the scientific standpoint. According to the Revised Statutes of Canada, 1886, chapter 47, the boundaries of the province of Manitoba were fixed briefly as follows: On the south, at the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude, which is the international boundary line; on the west by a line along the middle of the road allowance between the twenty-ninth and thirtieth ranges of townships west of the first principal meridian, which line falls between 101° and 102° longitude west of Greenwich; on the north by the middle of the road allowance of the twelfth base line, which is north latitude 52° 50'; on the east by the meridian of the northwest angle of the Lake of the Woods which, according to Professor Hind is 95° 50’ longitude west of Greenwich.

In preparing my own map full use has been made of the maps published: by Professor Hind in 1860, by the Dominion Government in 1874, and by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company at various times between 1880 and 1890, also those drawn by Mr. Shawe for Phillip’s Imperial Atlas, and those issued by the Tenth Census Report of the United States. I have also supplemented these by information gained in my own travels, as well as that supplied me by Messrs. Tyrrell, Nash, Macoun, Christy, and other observers.

|

In offering the following observations in their present shape, i. e., as they were made on the spot, without material condensation or generalization, I believe that I have taken not merely the best but the only right course under the circumstances. My original plan, as may be seen by the “notes” throughout, was to prepare something after a very old-fashioned model, but widening experience caused a considerable change of view. No one regrets more than myself their imperfectness, and, in some cases which I have pointed out, their unreliability. If I could see my way clear to revisit Manitoba in the near future I would gladly defer publication in the hope that I might first remove numerous doubts and fill many unfortunate blanks, but under existing circumstances there seems to be no course but to carefully revise my old journal and let it go forth for judgment. My own observations are supplemented by those of numerous observers in various parts of the province, and I have also endeavored to include all available records relating to distribution and all valuable published matter relating to the ornithology of Manitoba that has not appeared in a special work on birds. This excludes only Dr. Coues’s field notes * * * forty-ninth parallel, which, however, is constantly cited. In all the records I have given the exact words of the writer are quoted. Altogether I spent about 3 years in the province, my first visit extending from March 28, 1882, to November 16, 1883; my second from April 25, 1884, to January 27, 1885; my third from October 25, 1886, to January 12, 1887, broken only by occasional expeditions outside of our boundaries. Carberry was my headquarters, and except where otherwise stated all observations were made at that place. My companions, whose names appear, were Mr. Wm. G. A. Brodie, whose untimely death by drowning in the Assiniboine, May, 1883, robbed Canada of one of her most promising young naturalists; my brother, Dr. A. S. Thompson, with whom I lived, and Mr. Miller Christy. The last was with me during the latter part of the summer of 1883 and again for a few days in the July of 1884. He was the first ornithologist of experience that I had ever met, and I have to thank him for correcting in me many wrong methods of study that naturally were born of my isolation. My thanks are due to Dr. J. A. Allen, of the American Museum of Natural History; Prof. Robert Ridgway, of the Smithsonian Institution; and Dr. C. Hart Merriam, ornithologist to the U. S. Department of Agriculture, for the identification of numerous specimens, and other assistance, and especially to the last for placing at my disposal the manuscripts of Miss Yoemans, Messrs. Calcutt, Criddle, Nash, Plunkett, Small, and Wagner; to Prof. John Macoun, of the Canadian Geological Survey; Messrs. Christy, Nash, Hine, Hunter, and Guernsey, for numerous manuscripts, notes, and much valuable assistance; to Dr. R. Bell and Mr. James M. Macoun, both of the Canadian Geological Survey; Dr. William Brodie, of Toronto; Dr. Charles Carpmael, of the Canada Meteorological Department, and Mr. Ernest D. Wentle, of Montreal, for help in various ways; and to the Hudson’s Bay Company for access to the Hutchins manuscripts. Indispensable assistance in preparing the manuscript has been rendered also by my father, Mr. Joseph L. Thompson, and my cousin, Miss M. A. Burfield. The measurements throughout are in English inches. Ernest E. Thompson, 86 Howard street, Toronto, Ontario. July, 1890. |

The general features of the country have been ably and concisely described by Dr. Dawson in the report of the boundary commission (1875), as follows:

The first or lowest prairie level, is that of which the southern part lies along the Red River, and which, northward, embraces Lake Winnipeg and associated lakes, and the flat land surrounding them. A great part of its eastern border is conterminous with that of Lake Winnipeg, and formed by the rocky front of the Laurentian; but east of the Red River it is bounded by the high lying drift terraces surrounding the Lake of the Woods, and forming a part of the drift plateau of northern Minnesota. To the west it is limited by the more or less abrupt edge of the second prairie level, forming an escarpment, which, though very regular in some places, has been broken through by the broad valleys of the Assiniboine and other rivers. The escarpment, where it crosses the line, is known as Pembina Mountain, and is continued northward by the Riding, Duck, Porcupine, and Basquia Hills. The average height above the sea of this lowest level of the interior continental region is about 800 feet; the lowest part being that surrounding the Winnipeg group of lakes, which have an elevation of about 700 feet. From this it slopes up southward, and attains its greatest elevation—960 feet—at its termination far south in Minnesota. The edges of this prairie level are also, notwithstanding its apparent horizontality, considerably more elevated than its central line, which is followed by the Red River. Its width on the forty-ninth parallel is only 52 miles; its area, north of that line, may be estimated at 55,600 square miles, of which the great system of lakes in its northern part—including Lakes Winnipeg, Manitoba, Winnipegosis, Cedar, and St. Martin’s—occupy 13,900 miles. A great part of this prairie level is wooded more or less densely, and much of the low-lying land near the great lakes appears to be swampy and liable to flood. The southern part, extending from the boundary line nearly to the south end of Lake Winnipeg, includes the prairie of the Red River valley, with an area of about 6,900 square miles; one of the most fertile regions, and, at the same time, the most accessible portion of the Northwest.

The superficial deposits of this stage are chiefly those of a great lake which occupied its area after the glacial submergence. This part of the interior of the continent being the last to emerge from the Arctic waters and having been covered for a long time afterward by a sea of fresh water, held back either by drift deposits or by rocky barriers, which have subsequently been cut through, and which must have united all the lakes now found in the region into one sheet of water, which extended with narrower dimensions about 200 miles south of the boundary line.

The Red and the Assiniboine Rivers and their tributaries have not yet cut very deeply into its alluvial deposits and its surface is level and little furrowed by denudation.

The second steppe of the plains is bounded to the east, as already indicated, and to the west by the Missouri coteau, or edge of the third prairie level. It has a width at the forty-ninth parallel of, probably, 200 miles, though it can not there be strictly defined. Its total area is about 105,000 square miles, and includes the whole eastern portion of the great plains, properly so called, with an approximate area of 71,300 square miles. These occupy its southern and western portions, and are continuous westward with those of the third prairie steppe. To the south, the boundaries of this region appear to become more indefinite, and in the southern part of Dakota, the three primary levels of the country, so well marked north of the line, are probably scarcely separable. The rivers have acted on this region for a much longer time than on the last-mentioned, and are now found flowing with uniform currents in wide ditch-like valleys, excavated in the soft material of the plains, and often depressed from 100 to 300 feet below the general surface. In these the comparatively insignificant streams wander from side to side, in tortuous channels, which they only leave in time of flood. The surface of this prairie steppe is also more diversified than the last, being broken into gentle swells and undulations, partly, no doubt, by the action of denudation, and partly, also, as will appear, from the original unequal deposition, by currents and ice, of the drift material which here constitutes the superficial formation. The average altitude of this region may be taken at 1,600 feet, and the character of its soil and its adaptability for agriculture differ much in its different portions.

The third or highest prairie steppe may be said to have a general normal altitude of about 3,000 feet, though its eastern edge is sometimes little over 2,000 feet and it attains an elevation of 4,200 feet at the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

Obviously none of the third steppe would fall within our limits were it not for a curious exception that is presented by the Turtle Mountain, which, though belonging to the third steppe, stands like an island upon the open sea of the second. Of this Dr. Dawson says:

Turtle Mountain, an outline of the third prairie steppe, is a broken, hilly, wooded region, with an area of perhaps about 20 miles square (400 square miles), and slopes gradually upward from the plain around it, above which it is elevated, at its highest points, about 500 feet. It appears to be the culmination westward of the hilly drift region previously described, and forms a prominent object when viewed across the eastern prairie, from the contrasting somber tint of the foliage of its woods. From the west it can be seen from a distance of 45 miles, and when thus viewed has really much the general outline of a turtle shell. It is bisected by the forty-ninth parallel.

According to Mr. Tyrrell’s map, the altitudes of the large lakes, etc., to the west have hitherto been given fully 60 feet too low; as, however, I am without corrected figures for other points whose altitudes are given, I have elected to let older computations stand, and they may be taken as relatively correct.

“The sandhills” so often referred to, are certain low sand dunes that cover a considerable extent of country in the vicinity of Carberry. They are in most cases low undulations rather than hills, are sparsely covered with grass and dotted over with beautiful clumps of trees, while the hollows and flats are diversified with lakelets that swarm with waterfowl and lower forms of life. The general appearance of the sandhills country is quite park-like, and notwithstanding its unattractive name this region as a whole is the most pleasing to the eye and fuller of interest and varied pleasure for the naturalist than any other that I have seen in Manitoba. “The Big Plain” is an unusually level prairie extending from Carberry northward about 30 miles.

“The White Horse Plains” form a similar region between Shoal Lake and the Assiniboine.

“The Souris Plains” include the southwestern corner of Manitoba that is drained by the Souris River. This is a remarkably level region, entirely cleared of trees excepting in the river gorges, and diversified by numerous marshes and alkaline flats.

“Bluff” is, in Manitoban parlance, the name applied to any isolated grove of trees on the prairie. The term is never used here, as in the Western States, to mean an abrupt bank or escarpment.

Distribution of forest and prairie.—All that portion of Manitoba that lies to the eastward of the lowest prairie steppe, as above defined, is a rocky Laurentian region full of rivers and lakes of fresh water, and thickly wooded, being within the limits of the great coniferous forest. A wide strip of the flat country lying to the westward of Lake Winnipeg, likewise the elevated plateaus of Riding, Duck, and Porcupine Mountains, are also to be classed as parts of the northern forest. There is good reason for believing that at one time, not very remote, the rest of Manitoba was covered with a forest of aspens or poplars (Populus tremuloides), slightly varied by oak (Quercus macrocarpa), spruce (Abies alba et nigra), birch (Betula papyracea), etc., which has been removed by fire, so that trees are now found growing only in such places as are protected from the fires by streams, lakes, marshes, or sandy tracts where so little grass grows that the fire can not travel; consequently, notwithstanding the prevalent idea of Manitoba as a purely prairie region, there is more or less timber in nearly all parts of the country as indicated on the map. Thus I have endeavored to make a record of the distribution of forests in 1885, for evidently no natural feature is more likely to change in a few years than the extent of woodlands. The line limiting the coniferous forest on the south is copied from the forestry map issued with the Tenth Census report of the United States. It is suspiciously straight and even, but is doubtless correct when understood merely as a broad generalization. I regret that I am without the material necessary to define this limit more accurately. To the southward of Carberry is a small isolated forest of spruce that is known as the Spruce Bush or the Carberry Swamp, by which names it is herein referred to.

Water.—The province is plentifully, almost too plentifully, supplied with water. In addition to the numerous extensive lakes indicated on the map are thousands more of smaller extent, while the region of the Red River Valley in particular is diversified by vast stretches of marsh and lagoon. The various lakes are of two kinds, first the sweet water or live water lakes, fed and drained by living streams, teeming with fish and varying in size from that of a mere pond to that of Lake Winnepeg; second, the alkaline lakes, which are mere drainage basins and depend solely on evaporation for the removal of their accumulated waters.

They owe their alkaline impregnation not to anything of the nature of salt-bearing strata, but to the continual influx and evaporation of surface water very slightly impregnated with alkali through running over the prairies strewn with the ashes of the annual fires. These “dead waters” never, so far as I know, contain fish, but they are usually swarming with a species of amblystoma and numerous kinds of leeches and aquatic insects. These lakes abound on the prairies and in the sand hills, but are usually of very small extent. They have, I believe, several peculiar species of sedge, and are especially frequented by certain kinds of birds that seem to avoid the fresher waters, e. g., Baird’s Sparrow, Avocet, etc.

Salt springs, etc.—The following extract from Professor Macoun’s well-known work on “Manitoba and the great Northwest, 1883,” will prove an interesting item of physiography:

Lying farther south [than the Silurian], and possibly underlying the greater part or the western side of the Manitoba Plain, is the Devonian Series. These rocks are known to be largely developed on both sides of Lakes Manitoba and Winnepegosis. Numerous salt springs are found in connection with them, and during the last summer the writer saw salt springs and brooks of strong brine flowing from them in various localities at the head of Lake Winnepegosis. The subjoined list of salt springs known to occur on Lakes Manitoba and Winnepegosis may tend to excite interest in these extensive deposits:

1. Crane River, Lake Manitoba.

2. Waterhen River, Dickson’s Landing.

3. Salt Point, east side of Lake Winnepegosis.

4. Salt Springs, Winnepegosis.

5. Pine River, Winnepegosis.

6. Rivers near Duck Bay.

7. Turtle River, Lake Dauphin.

8. Swan or Shoal, two localities.

9. Salt River, flowing into Dawson’s Bay.

10. Numerous salt springs and bare, saturated tracts of many acres in extent on Red Deer River, which flows into the head of Dawson’s Bay, Lake Winnepegosis. For 10 miles up this river salt springs are quite frequent, and excellent salt was collected in three places, where it formed a crust on the surface of the ground. Some springs were examined where a respectable rivulet of strong brine issued from them, as clear as crystal, and evidently quite pure. All the springs and marshes seen were bordered with seaside plants, and one of them, which has never been found from the seacoast before in America, was found in abundance. The plant referred to is Sea-Side Plantain (Plantago maritima).

The following extract from Professor Hind’s report (1858) shows that this line of saliferous strata goes right across our province:

Near and west of Stony Mountain many small barren areas occur, covered with saline efflorescence; they may be traced to the Assiniboine, and beyond that river in a direction nearly due south to La Riviére Sale and the forty-ninth parallel. These saline deposits are important, as they in all probability serve, as will be shown hereafter, to denote the presence of salt-bearing rocks beneath them, similar to those from which the salt springs of Swan River, Manitoba Lake, and La Riviére Sale issue.

Meteorology.—I have not been able to obtain the material necessary for a general chapter on the meteorology of Manitoba, and must content myself with a few statistics taken from Professor Bryce’s article on Canada in the Encyclopædia Britannica.

The mean annual temperature for 11 years, (1871-1881, inclusive), taken near Winnipeg, was 33.06°, the maximum 95.34°, the minimum -10.51°; the mean amount of rain, 16.977 inches; the mean amount of snow, 52.72 inches; the mean total precipitation of rain and snow, 23.304 inches; the mean height of the barometer, 29.153. The mean average temperature for the years 1880 and 1881 was as follows: January, 2°.9; February, 3°; March, 9°; April, 30°.2; May, 51°.2; June, 63°.6; July, 65°.9; August, 64°.8; September, 51°.3; October, 40°; November, 14°.6; December, 0°.6; the year, 32°.6.

The isotherms indicated on the map were taken from the map prepared to Professor Macouns’ work.

Topography.—The topography of Manitoba is somewhat perplexing through the duplication of names. Many, such as Pelican Lake, Swan Lake, Shoal Lake, Rat Creek, etc., appear several times over. None of these duplications have been entered on the map, with the exceptions of Shoal Lake and Boggy Creek. In the first case I have added the word “West” to the name of the lake which is of secondary importance and probably of later naming. In the second the three creeks are distinguished as Boggy Creek, Big Boggy Creek, and Little Boggy Creek. Every name referred to in the notes, with exceptions noted herein later, will be found on the map, with many additional ones that are of importance. Frequent allusion is made to Professor Macouns’ journeys and the region observed by him in making them. These expeditions were as follows: 1879, from Winnipeg to Fort Ellice by water and thence up the Qu’Appelle River; 1880, from Winnipeg to Grand Valley, now Brandon, by water and thence overland to Moose Mountain; 1881, from Winnipeg to Portage la Prairie by rail, thence overland to Totogon down Lake Manitoba by boat into Waterhen River and into Waterhen Lake, and back by the western channel into Lake Winnepegosis, and along the western shore of this lake into the larger bays, up Swan River to Swan Lake, then back to Winnepegosis and up Red Deer River to Red Deer Lake, up its southern affluent across country to Livingstone and down the Assiniboine to the railroad at Brandon.

Humphrey’s or McGee’s Lake, Hope’s Lake, Smith’s Lake, and Markle’s Lake are small drainage lakes near Carberry. White Horse Hill, Kennedy’s Plain, and De Winton Slough are also close to Carberry. These have been omitted from the map, as they are too small for the scale on which it is drawn.

The following places outside of the province have been mentioned to extend or explain the distribution of certain species:

Carleton House: On the north branch of the Saskatchewan.

Cumberland House: On the Lower Saskatchewan.

Fort Pelly: On Assiniboine River, 10 miles west of Duck Mountain.

Fort Qu’Appelle: On Qu’Appelle River, 100 miles up from its junction with the Assiniboine.

Moose Mountain: Assiniboia, 35 miles westward of Manitoba, about latitude 49° 40´ north.

Nelson River: The outlet of Lake Winnipeg, situated at its north end.

Norway House: North end of Lake Winnipeg.

Rat Portage: On the Lake of the Woods, where it is touched by the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Red Deer River: Flowing into Red Deer Lake, at the northwest corner of the province.

Severn House: On Severn Lake, at 54° 5´ north latitude and 92° 30´ west longitude, about 150 miles northeastward of the province.

Selkirk: Lake Winnipeg, about 40 miles north of the northern boundary.

Touchwood Hills: 30 miles north-northwest of Fort Qu’Appelle.

Trout Lake House: On Trout Lake, at 53° 50´ north latitude and 91° west longitude, about 200 miles northeast by east of the province.

White Sand River: A tributary of the Upper Assiniboine, near the northwest corner of the province.

Tolerably common summer resident in Red River Valley, chiefly towards the northward, as follows: Quite common at Shoal Lake, near Lake Manitoba, and less so at Redburn (Hine). A rare summer resident along Red River (Hunter). Breeding in vast numbers at Shoal Lake and Lake Manitoba, not elsewhere (D. Gunn). “Clark’s Grebe,” Shoal Lake (Brewer). Breeding on Lake Manitoba and very abundantly in the marshes of Waterhen River, between it and Lake Winnepegosis. I took great numbers of eggs on Waterhen River and the south end of Waterhen Lake (Macoun).

I did not meet with this bird in any part of western or southern Manitoba, but at Winnipeg I was shown several specimens taken near Redburn, where it is somewhat common, and others from Shoal Lake, where it is quite plentiful. These facts, together with the following statement by Professor Macoun, are the more interesting when we consider that for a long time this grebe has been considered a bird of the Pacific region.

In his work on the Northwest, Professor Macoun writes:

On Waterhen River and Lake the Western and Red-necked Grebes breed in great numbers. Their nests are built on the old sedges and rise and fall with the water. Here the Indians collect large numbers of eggs in the proper season, and one old fellow, last season, astonished me by the remark that he could have fresh eggs all summer. On inquiry I learned that he went regularly to the same nests and never took all the eggs so that he kept the poor bird laying all summer.

Mr. D. Gunn makes the following remarks on this species at the lake in question:

The annual resort of the Podiceps occidentalis to Shoal Lake is, as has been observed, “remarkable.” From the most reliable information that I could obtain from the Indians at this place it has never been seen on the Red River nor on Lake Winnipeg, and I have never heard of its having been seen anywhere in what is commonly known as Rupert’s Land, except at Shoal Lake and Manitoba, and I may add that it is also remarkable that there are very few grebes to be found in any other of the bays connected with the lake, although all these bays abound in reeds and rushes. Possibly these birds prefer the bay on the north point on account of its being sheltered from the wind, and probably a greater facility for obtaining food in that locality may influence them in the choice they make. I am inclined to think that the large grebes feed on aquatic plants; I opened several of their gizzards and found nothing in them but grass. The Western Grebes, when seen in groups on the smooth, unruffled waters of the lake, make a splendid appearance, sometimes raising themselves out of the water, and flapping their wings, their white breasts glistening in the sun like silver. They are not timorous, but when alarmed they sink their bodies in the water, and if the object of their fear still presents itself they plunge head foremost and dive and continue a long time under the water, often disappointing the expectations of their pursuers by reappearing in a different direction from that anticipated. They make their nests among the reeds on the bent bulrushes of the last season; the frame or outer work is of reeds and lined with grass from the bottom and reed leaves. The nest is nearly on a level with the surrounding water and may be said to float at its “moorings,” held there by the reeds. We found hundreds of these nests containing two, three, and four eggs each; I believe six to be the highest number we found in any one. We took thirteen grebes, of which the males were larger than the females; the largest male measured, before skinning, 27¼ by 36¼ inches and 14 inches round the body at the head of the wings. The largest female measured 24½ by 32½ inches. We shot not a few of them in the act of leaving their nests, and most of them on being skinned proved to be males, which fact inclines me to believe that the male bird takes his turn in sitting on the eggs.

Summer resident chiefly of the shallow, fish-frequented lakes to the northward. Winnipeg: Summer resident; very rare; only 4 specimens taken up to 1885 (Hine). Breeding in considerable numbers at Shoal Lake; comparatively rare in Red River region (D. Gunn). Specimen from Red River settlement in Smithsonian Institution (Blakiston). Breeds abundantly in the marshes of Waterhen River and south end of Waterhen Lake, where I took great numbers of its eggs (Macoun). Duck Mountain; breeding (Thompson).

On June 18, 1884, while hunting at Duck Mountain, above Boggy Greek, with my brother, we came to a small lake and parted to go around it in different directions. When we met, he showed me a nest which he had found among the reeds in 2 feet of water. It was a mere floating mass of wet rushes, and had been moored by a few growing rushes whose tops had been incorporated with the structure. It contained 3 eggs, which the bird was hastily covering with more rushes when he first saw her. From his description, and from what I could see at 200 yards distance, it was apparently an adult Red-necked Grebe, but the bird was too shy to admit of the identification being completed in the only perfectly reliable way.

As there are no fish in these isolated mountain lakes, these birds probably live largely on amblystomæ, crawfish, and insects.

Abundant summer resident of general distribution; very abundant; breeding at Pembina and the base of the Turtle Mountain (Coues). Lake Winnipeg (Murray). Red River (Kennicott). Common summer resident in Red River Valley (Hunter). Common about Winnipeg (Hine). Very common on Red River, and breed in the marshes near Shoal Lake (Gunn). Portage la Prairie; common summer resident (Nash). Observed in the ponds from Turtle Mountain to Brandon, in May, 1882; commonly breeding in all the ponds about the Big Plain, being the most abundant Grebe of the region; common also from Carberry to Rapid City and thence west to Fort Ellice, and in the whole region on both sides of the Assiniboine, northward to Duck Mountain (Thompson). Abundant on Waterhen River; breeding; they give the name to the river; the common Grebe of the prairie ponds (Macoun). Shell River; 1885, first seen, two on May 3; afterwards seen every day; it is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Trout Lake (Murray).

On July 20, 1883, in a lake near “The Gore,” shot a Horned Grebe. It had saved itself once or twice by diving at the puff of smoke, so I sought the cover of the bushes and fired through an opening, and as no smoke was visible I got the bird. It was an adult male; length, 14 inches, extent 24 inches; moulting; iris blood red, with an inner circle of white around it; basal region and part of lower mandible adjoining covered with bare red skin; in examining the eye, I squeezed out a leech, that was sometimes like a No. 4 shot or again like a small needle.

On June 3, 1884, while traveling on the Birtle trail from Rapid City I noticed a pair of Horned Grebes in a small pond. I fired and disabled one. On wading in I found it was shot in the eye and was perfectly blind, though otherwise unhurt. Having heard sundry curious theories about the way in which these birds move their feet, I kept it alive for observation. When ordinarily swimming the feet strike out alternately, and the progression is steady, but sometimes both feet struck together, and then the movement was by great bounds and was evidently much better calculated to force the bird over an expanse of very weedy water or through any tangle of weeds or rushes in which it might have found itself. When lifted out of the water the feet worked so fast as to be lost to the eye in a mere haze of many shadowy feet with one attachment. When placed on the ground it was perfectly helpless. At nights I laid it by my side on the grass, and each morning I found it still in the same place. During the day I carried it in a bucket swung under the wagon. It often tried to leap out of this, but never succeeded. On the second day of its captivity it laid an egg, which was like a duck’s egg with a heavy coat of whitewash. On the third day, after the wagon had crossed some rough ground, which had set the pail violently swinging, I found the grebe was gone. All the specimens of cornutus that I have examined have the eye all blood-red except a thin ring of white which immediately surrounds the pupil.

On August 21, 1884, shot a Horned (?) Grebe in the lake southwest of here. Several young ones were seen. No doubt the species breeds there as in all the small drainage ponds in this region, although they are totally devoid of fish. The only animal food available for the grebes in there is amblystomæ, frogs, leeches, and insects.

Dishishet Seekeep or Little Diver. This bird differs but little from Mr. Pennant’s small grebe. It weighs 5½ ounces, harbors in our fresh waters, where it builds a floating nest of grass, laying from three to five eggs of a white color; the heat of the bird causing a fermentation in the grass, which is a foot thick, makes a kind of hotbed, for (please to observe) the water penetrates through the grass to the eggs. (Hutchins’s Observations on Hudson Bay. MSS. 1782.)

Common summer resident, breeding abundantly on Turtle Mountain and at points along Mouse River, near the boundary (Coues). Common summer resident in Red River Valley (Hunter). Winnipeg: Summer resident tolerably common (Hine). Breeding in great numbers at Shoal Lake and on Red River (D. Gunn). Quite common on pools in prairie regions (Macoun). Very numerous in this bay (Grebe Bay, Shoal Lake). They make their nests on the bulrushes, composed of the same material. We found as many as six eggs in some nests, but in the greater number of nests only four. They are very shy and expert divers, are very common on the Red River, and breed in the marshes near the lake (D. Gunn).

Common summer resident in all waters, living and dead; breeding at Pembina and on ponds at the base of the Turtle Mountain (Coues). Winnipeg: Summer resident; tolerably common (Hine). Red River Valley: Summer resident; common; breeds at Shoal Lake (Hunter). Portage la Prairie; very abundant; summer resident on every lake, slough, or pond large enough to give them sufficient “water privilege;” arriving as soon as the ice is out and departing when their haunts are frozen over. First seen, May 6, 1884, April 24, 1885, April 19, 1886 (Nash). Frequently observed in the ponds from Turtle Mountain to Brandon; in May, 1882, common and breeding in the ponds about Carberry, also at Rapid City (Thompson). In immense numbers (killed four at a shot) in August and early part of September on the headwaters and marshes of Swan River; abundant on all pools south of Touchwood Hills; apparently more northern than the preceding (Macoun). Shell River, May 4 (Calcutt).

On June 30, 1882, at Rapid City, found a Pied-billed Grebe lying dead on the road. This species seems to be very abundant throughout the country from here to Carberry, and from Carberry to Turtle Mountain, for the peculiar call note “pr-r-r-r-r tow tow tow tow” (that I ascribe to this species) is heard in nearly every marsh throughout the region indicated.

On August 12, 1883, I came on a pair of Pied-billed Grebes in McGee’s Lake, Carberry. Instead of diving they commenced flapping over the surface and excited my curiosity so that I shot them both. They were both Dabchicks, and I found they would not dive because the water was very weedy at that place. Their gizzards were full of water insects and feathers. These last are commonly found in gizzards of Grebes. I know of no explanation of this fact, unless it be to muffle the movements of newly swallowed living prey.

On September 13, 1884, at Portage la Prairie, found Dabchicks here yet. They seem more numerous here than at Carberry.

Summer resident on the larger fish frequented lakes. Summer resident; abundant, and breeding on Lake Winnipeg and the larger rivers (Hine). Swampy Island: 1885, first seen, four, on May 30; next seen May 31; rare around this island; not breeding here; common at northern end of lake in fall; last seen September 27; in 1886, first seen, twenty, on May 14 (Plunkett). Oak Point: 1884, arrived May 1 (Small). Portage la Prairie: Tolerably common on Lake Manitoba throughout the summer, arriving with the first general thaw in spring and retiring when driven out by the frost (Nash). Common only on the northern lakes in the forest country; saw some on Red Deer Lake; never more than a pair together; never saw it in the prairie region (Macoun). Riding Mountain: June, 1884 (Thompson). Shell River: 1885, first seen, a pair on May 4; afterwards, seen every day; is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident, breeds; arrives April 28 (Guernsey). Severn House (Murray).

Athinne moqua, or Great Northern Diver. This elegant bird is seldom seen on the seacoasts, but resides among the lakes above 100 miles to the southward of York Fort, for which reason they are called the inland loons. (Hutchins’s MSS. Observations on Hudson’s Bay, 1782.)

Recorded by Andrew Murray, from Severn House, and therefore probably Manitoban.

Winnipeg: Rare (Hine). Norway House (Bell).

Assee moqua, or Red-throated Diver. * * * It appears in these parts when the rivers are open and retires about the end of September. Its note is harsh and disagreeable, like squalling. They make no nest, only lining the place with a little down from the breast, on which they deposit their eggs towards the end of June; they are of a stone color and only two in number. The young ones fly before the end of August. They live chiefly on fish and are excellent divers, and so very troublesome to the nets that I have this summer taken out fourteen of them that were caught in one tide at a single net. (Hutchins’s Observations on Hudson’s Bay, 1782.)

Severn House (Murray). This species may be named as probably Manitoban on the above grounds.

Summer resident about the larger bodies of water; breeding in great numbers at Lake Winnipeg (D. Gunn). Specimen from Nelson River, in Smithsonian Institution (Blakiston). Oak Point: 1884, arrived April 21; 1885, first seen, two, on April 18; next seen, two, on 19th; is common, and breeds here (Small). Breeding in all the large prairie lakes (Macoun). Portage la Prairie: Occurs during the spring and autumn migrations (Nash). Severn House (Murray).

The island on which we were detained by a storm, is one of the Gull-egg group, which, with a point of land protruding from the main land, forms a pretty good harbor on the south side of the neck of the great promontory. The Indians were nearly destitute of provisions and followed us to the island, where they fortunately got a plentiful supply of eggs and young gulls; but having little ammunition, they brought down only a few old ones, although they hovered in countless numbers over the island, screaming at the wholesale destruction of their young brood. (Hurd, August 24, 1858.)

Summer resident, near Mouse River, on the boundary, in September (Coues). Winnipeg: Summer resident, tolerably common, and at Lake Winnipeg (Hine). North, in summer, to Lake Winnipeg (Brewer). Breeding in all the lakes of any size (Macoun).

Summer resident about the large lakes. Winnipeg: Summer resident; abundant; breeding in the prairie marshes of the neighborhood (Hine). Swamp Island: 1885, first seen, two, on May 28; next seen, May 29, after which it was common; it breeds here, and is an abundant summer resident; in fall, last seen September 25; 1886, first seen, six, on May 18; bulk arrived May 20 (Plunkett). Breeding at Selkirk Settlement, Red River Settlement, and in numbers at Swan Creek, Oak Point, Lake Manitoba (D. Gunn). Shoal Lake: May 15, 1887; common (Christy). Portage la Prairie: Common in spring migration; in 1884, first seen April 21 (Nash). Breeding abundantly on Lake Winnepegosis, 1881 (Macoun). Carberry: A common spring migrant (Thompson). Turtle Mountain: Young (Coues). Shell River: 1885, “Black-Headed Gull,” first seen, two, on April 24; next seen, nine, on May 2; a transient visitant passing north and not remaining any time or breeding (Calcutt).

Summer resident about the larger lakes. Winnipeg: Tolerably common here in fall (Hine). A few breeding in the marsh of Swan Creek, not far from Shoal Lake (D. Gunn). Breeding in great abundance on all the large lakes of the prairie region, chiefly west of Manitoba (Macoun). One in Smithsonian Institution from Nelson River (Blakiston). Portage la Prairie: Abundant during the spring migration, and some probably stay to breed, as I have occasionally seen single birds about the prairie sloughs during the summer (Nash). Severn House; fortunately several specimens of this gull have been received; it is rare in collections, but would appear not to be so in Hudson’s Bay (Murray).

Summer resident about the large lakes; breeding in large numbers on the borders of Lake Winnipeg in the latter part of May; at Shoal Lake, saw Forster’s terns in considerable numbers; they nest among the reeds; Selkirk Settlement (D. Gunn). Shoal Lake, May 15; common (Christy). Breeding abundantly in Lake Manitoba, Waterhen River, and Lake Winnepegosis (Macoun). Portage la Prairie: Abundant during the spring and autumn migrations; probably breeds, as I have seen a few in summer (Nash).

Common summer resident on the large lakes; feeding largely on small fish. Winnipeg: Summer resident; tolerably common (Hine). One taken on Lake Winnipeg, June 16 (Humicalt). Breeding on Lake Manitoba, Waterhen River, and Lake Winnipegosis (Macoun). Portage la Prairie: Tolerably common during spring and autumn migrations; a few remain about Lake Manitoba during the summer (Nash).

There are numbers of terns breeding annually at Shoal Lake; some of them on small, gravelly islands. These form their nests by removing the gravel, making hollows in which they lay their eggs; others of them take up their abode among the reeds and rushes. Here, with great industry and ingenuity, they make their nests of reeds and grass, fixing them in their place to keep them from floating away. When in Lake Winnipeg, in 1862, I observed that the terns which occupied sandy and gravelly islands made their nests as those do on the gravelly islands in Shoal Lake; and the terns found on the rocky island on the east side of the lake chose for their nests depressions and clefts in the surface of the rocks. These they line carefully with moss; three or four eggs being laid in each nest; thus exhibiting a remarkable example of instinct, which teaches these little creatures that their eggs laid in soft sand and in loose gravel are safe without any lining to protect them, but that when laid in hollows and clefts of rocks, lining to protect their eggs and young from injury by these hard, and at night cold, materials would be indispensable. (D. Gunn.)

Abundant summer resident; chiefly about the prairie ponds, dead waters; breeding at Pembina; Mouse River at the boundary (Coues). Winnipeg: Summer resident; abundant (Hine). Abundant in Red River and Selkirk Settlements (Brewer). Prairie Portage; plains of the Souris (Hind). Portage la Prairie: Abundant summer resident on all the large prairie sloughs, in which they breed; first seen, May 11, 1884, May 25, 1885; last seen, September 9, 1884 (Nash). Breeding very abundantly in all marshes from Portage la Prairie westward, 1879, and in less numbers in the wooded region, but generally distributed (Macoun). Carberry: Abundant; summer resident; breeding also in all ponds along the trail from Carberry to Port Ellice (Thompson). Brandon: Breeds in great numbers (Wood). Shell River: 1885, first seen, eleven, on May 18; seen every day afterwards; is common all summer, and breeds here; Indian name, “K’ask” (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; arrives May 18 (Guernsey). Severn House (Murray).

On June 11, 1882, went in the morning with two brothers to the lake in the sand hills east of old Dewinton; saw there large numbers of marsh terns. They appeared to be nesting in a weedy expanse far out in the lake, but it was surrounded by deep water, so that I could not come near it to seek for eggs. The birds came flying over my head, in company with numbers of blackbirds, and resented my intrusion by continually crying in their characteristic manner.

August 4. The black terns are beginning to gather in flocks; leave the ponds and skim about over the open prairie.

On July 8, 1883, went southwest to Smith’s Lake; found a number of tern’s nests, just finished, apparently, as they were clean, but empty, and the old birds continued flying above us and screaming their resentment.

On July 5, 1884, at McGee’s Lake, Carberry, I found the terns just beginning to lay. Each nest is a mere handful of floating reeds, slightly moored to others growing in the deep water, where they are found. The whole structure is just on a level with the surface of the water and entirely wet; on this are the eggs, much the same color as the reeds, and as wet as eggs can be.

It is a remarkable fact that, although this species is abundant in all parts of southwestern Manitoba, and I have often searched in various lakes with a flock of terns screaming about my ears, yet I have never before found either nest or eggs. On this occasion I found three eggs in one nest; several nests with two eggs; one or two with one, and one or two empty nests just completed.

On July 9 the terns were numerous everywhere on the prairie. Timed and counted the wing beats of several as a basis for calculating their rate of flight; one made 54 beats in 9 seconds; another, 28 beats in 9 seconds, a third 30 in 10 seconds. July 6, observed one make 27 beats in 10 seconds. July 12, saw another make 15 beats in 5 seconds, showing that about 3 is the average number of beats to the second. July 5 I had an opportunity of measuring the distance a tern covers with 8 beats; it was 24 yards.

August 14: Terns are abundant now on the open prairie; it is a common sight to see this bird zigzagging about in pursuit of the large dragon flies, until, at length, having secured as many as it could conveniently carry, it suddenly ceased the fantastic maneuvering for the swifter beeline, and made straight for its twin nestlings in the reedy expanse of some lake far away.

To-day, I made a calculation of the speed; one bird covered 70 yards with 14 beats, i. e., 5 yards per beat; I find they usually give 3 beats per second; this, therefore, is 15 yards per second or 31 miles per hour; much less than I expected. This black inland member of a white marine family is abundant about all the weedy sloughs and lakes of the Manitoban prairie regions. It seems not to subsist on fish at all, but chiefly on dragon flies and various aquatic insects. It finds both its home and its food in the marshes usually, but its powers of flight are so great that it may also be seen far out on the dry open plains scouring the country for food at a distance of miles from its nesting ground.

The voice of the species is a short, oft-repeated scream, and when any known enemy, be it man or beast, is found intruding on the privacy of their nesting ground the whole flock comes hovering and dashing about his head, screaming and threatening in a most vociferous manner. Under such circumstances it is the easiest thing imaginable to procure as many specimens as may be desired. When one of the flock falls wounded in the water, its fellows will repeatedly dart down and hover low over it, but I have never seen any attempts made to assist it in escaping, after the manner ascribed to some of the family.

Besides aquatic insects the Black Tern feeds largely on dragon flies which it adroitly captures on the wing. The bird may frequently be seen dashing about in a zigzag manner so swiftly the eye can offer no explanation of its motive until, on the resumption of its ordinary flight, a large dragon fly is seen hanging from its bill and sufficiently accounts for the erratic movements of the bird. After having captured its prey in this way I have frequently seen a tern apparently playing with its victim, letting it go and catching it again, or if it is unable to fly, dropping it, and darting under it to seize it again and again before it touches the water. After the young are hatched, a small flock of the old ones may be seen together leaving the pond and winging their way across country to some favorite dragon-fly ground. Their flight at first is uncertain and vacillating, but as soon as one has secured its load it returns with steady flight and in a straight line to its nest.

Under ordinary circumstances I was always impressed with the idea that the tern was very swift and entered into a series of elaborate calculations to ascertain the rate of its flight. A large number of observations resulted in an average of three wing-beats per second, with the greatest of regularity; another series of observations, not so satisfactory, allowed a distance of 5 yards to be traversed at each beat. This gave only the disappointing rate of something over 30 miles per hour, but this was at the uncertain foraging flight. Once the mother tern has secured her load of provender, a great change takes place, as already mentioned; she rises high in air, and I am sure she doubles her former rate of speed, and straight as a ray of light makes for home. It is said that many birds can not fly with the wind; not so the tern; for now, if there be a gale blowing her way, she mounts it like a steed and adds its swiftness to her own, till she seems to glance across the sky, and vanishes in the distance with a speed that would leave far behind even the eagle, so long the symbol of all that was dashing and swift.

Summer resident about the large lakes of the westward region when there is plenty of fish; once observed on Red River near Pembina (Coues), Winnipeg: Summer resident; not rare, and found breeding at Lake Winnipeg; occasional on Red River (Hine). Breeding at Shoal Lake and Selkirk Settlement (D. Gunn). Shoal Lake: Plentiful; breeding; May 16, 1887 (Christy). Ossowa: Breeding (Wagner). Portage la Prairie: Tolerably common during the spring migration, on the Assiniboine and Red Rivers, and the wooded sloughs adjacent to them, but very seldom seen in the autumn; first seen April 24, 1885, April 20, 1886; on October 8, 1886; I saw one flying up the Red River southward; these birds are very wild and difficult of approach when on the water, rising with a great flapping before one can get within 200 yards of them (Nash). Very abundant; breeding on Lake Winnepegosis in 1881 (Macoun). Shell River: 1885, first seen, four, on May 13; next seen, two, on May 14; a transient visitor only; not breeding, (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Rather common summer resident; April 25, breeding north of the Touchwood Hills; nesting on the trees growing on islands in the lakes (Guernsey).

Fort Qu’Appelle, May 19, 1885. The Cormorant comes here in large flocks towards the end of April; it is called by half-breeds the Crow Duck; in its flight it flaps for three or four strokes and then sails; it is an expert diver. The half-breeds say that it builds on islands in the lakes north of here, building its nests on trees. They say that when a man lands on one of their breeding places the birds fly over him and drop their excrement on him. I have been told this by several. They do not breed here that I know of, but there are always several knocking about during the summer; they sit on the bars with the pelicans. (Geo. F. Guernsey).

Common summer resident about the large lakes; one taken at Pembina in May; observed at Mouse River on the boundary in September (Coues). Winnipeg: Summer resident; common about the large lakes; breeding at Shoal Lake (Hine). Red River Valley: Summer resident; common; breeds at Shoal Lake (Hunter). Shoal Lake (Christy). Breeds in the smaller lakes near Lake Winnipeg, and northwestward; several specimens shot in Lake Winnipeg in October, 1880 (Bell). Swamp Island: 1885, first saw two on May 24; next seen May 31, after which it was common; it breeds here; in fall, last seen September 12, 1886, first saw, two, on April 29; bulk arrived May 27 (Plunkett). September 1, 1884, saw a flock of five on Lake Manitoba; the only ones I ever saw (Nash). Waterhen River: October 3, 1858, a large flock of pelicans, wheeling in circles far above, suddenly formed into an arrow-headed figure, and struck straight south; Oak Lake, some Pelicans (Hind). In great numbers at the head of Lake Winnepegosis or about half way up, and evidently breeding, 1881 (Macoun). Carberry: November 5, 1886, found remains of a dead pelican in the hills near Smith’s Lake; only record (Thompson). Dalton: 1889, first saw one on May 4; next seen, May 5; rare (Yoemans). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; very plentiful on the lakes last year (1884); towards the migratory season I saw flocks of upwards of 500 birds (Guernsey). Pelican observed in numbers at the Grand Rapids, where the Saskatchewan enters Lake Winnepeg, on the 25th of September, and a few days after a scattered one or two; I believe they do not range east of Lake Winnipeg (Blakiston).

These birds until the last few years were in the habit of breeding in large numbers at Shoal Lake, 50 miles from Winnipeg. In the summer of 1878, on the 1st of June, I counted six hundred of their eggs (?) in nests on a small island of about half an acre in extent. The nests consist only of a slight depression in the sand. These birds and the cormorants are great friends; the nests of the latter were intermixed everywhere with those of the pelicans. I counted seven hundred eggs of the cormorant on this spot. Although the pelican’s home and nesting place is an abode of filth, they keep themselves exceedingly clean. Their flight I consider more beautiful and graceful even than that of the swan. (Richard H. Hunter in MSS.)

Fort Qu’Appelle, May 19, 1885. Some years the pelicans are more numerous than others. Last year they were very thick all summer, and towards the end of summer it was no unusual thing to see forty or fifty in a flock sitting on the water. They are reported to breed in large numbers on Long Lake, 40 miles west of here. (George F. Guernsey in MSS.)

Summer resident, frequenting only living water. Winnipeg: Summer resident; rare; Lake Winnipeg (Hine). Red River Valley: Summer resident; common; breeds at Shoal Lake (Hunter). Breeds abundantly on the rivers emptying into Lake Winnepegosis, and on all the rivers visited by me in Manitoba; I never observed this bird on still water during the breeding season; they feed only on fish, and are found only on clear running streams where fry are abundant (Macoun). Qu’Appelle: Tolerably common summer resident; May 5 (Guernsey).

Summer resident, chiefly on living waters. Winnipeg: Summer resident; rare; Lake Winnepeg (Hine). Red River Valley: Summer resident; tolerably common; breeds at Shoal Lake (Hunter). Breeds in all the northern streams and ponds; feed largely on vegetable matter and are quite edible (Macoun). Carberry: August 21, 1884, at Hope’s Lake, shot a merganser; rare here (Thompson). Qu’Appelle: Tolerably common; summer resident; May 1 (Guernsey). Trout Lake, Severn House (Murray).

Summer resident, chiefly inhabiting drainage, that is, dead water; breeds; Turtle Mountain and Mouse River along the boundary (Coues). Dufferin: Arrived between April 20 and 25 (Dawson). Winnipeg: Summer resident; common; breeding at Lake Winnipeg (Hine). Portage la Prairie: Tolerably common; summer resident; first seen April 27, 1885, April 23, 1886; abundant on La Salle River and on Horse Creek near Westbourne (Nash). Found in all the smaller ponds and lakes; very common in streams around the Porcupine Mountain; feeding on vegetable substances and quite edible, unlike M. americanus (Macoun). Carberry: Tolerably common summer resident; breeding (Thompson). Shell River: 1885, first seen, eight, on May 11; is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; arrives April 20 (Guernsey). Trout Lake (Murray).

Very abundant; summer resident; general distribution in grassy freshwater marshes, etc.; breeds abundantly throughout the region in suitable places, from Pembina along the boundary to the Rockies (Coues). Dufferin: Arrived between April 15 and 20 (Dawson). Winnipeg: Summer resident; abundant (Hine). Ossowa: Common; breeding; 1885, first seen, two, on April 6; next seen, April 13 (Wagner). Swampy Island: 1885, first seen, two, on April 16; next seen, April 20; became common April 26; breeds here in fall; last seen October 1; 1886, first seen, two on April 16; next seen, April 17; (Plunkett). Oak Point: 1885, first seen, two, on April 7; next seen, April 8; became common on April 11; breeds here (Small). Portage la Prairie: 1884, very common; summer resident; first seen, March 30; a few sometimes remain till after the snow covers the ground (Nash). The most abundant duck of the Northwest, breeding in nearly all the marshes north of the boundary (Macoun). Carberry: Abundant in migration; a few breed; Souris Plain; Turtle Mountain; Long River; Fingerboard; near Rapid City; near Two Rivers; Pine River; Portage la Prairie (Thompson). Brandon: April 13, 1882 (Wood). Dalton: 1889, first seen, four, on March 21; next seen on March 23; became common on March 26; breeds here (Youmans). Shell River: Common summer resident; breeds; in 1885, first seen, twelve, on April 6; afterwards seen every day (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds April 5 to 15 (Guernsey). Trout Lake Station and Severn House (Murray). Near Cumberland House are found in vast multitudes (Hearne, 1773).

June 11: While roaming in Spruce Bush, to-day, I came suddenly across a wild duck (Mallard) with her newly hatched brood. She was leading them to the water, which was a considerable distance away, perhaps a quarter of a mile, and in this locality the forest was high and dry. The old duck ran to meet me and then put in practice all the usual stratagems to cover the retreat of her brood; meanwhile the little ones scattered and ran, “peeping” in all directions, and soon all had hidden themselves from view, except five, which I caught. The remaining four or five I did not try to get, but left them for the mother to gather together again. My little captives I took home with me, fondly believing I could rear them.

On October 30, 1886, saw three Mallard at Smith’s Lake. I have often lain in the long grass on the bank of some pond and watched the whole family as they played about on the glassy surface, now splashing the water over the backs, apparently to show how they mean to do it when they are big rather than for any present benefit, and now rushing pattering over the surface in pursuit of some passing fly and generally with success crowning the effort, for when young they feed almost exclusively on insect food. I touched one of the tall stems so that the top shook; the watchful mother failed not to observe that there was something in the rushes, and slowly led her brood in another direction; or if I stood up in full view, she gave to her startled brood the watchword of alarm, which to judge from her actions may be translated “scatter and run for your lives into the rushes while I divert the brute’s attention.”

There have been times when it was the necessity for food that led me where I have observed such scenes as that described, but I can say truly that each time the brave mother was allowed to go in peace and the hunt was prolonged until another though perhaps a less palatable victim was found and sacrificed.

They arrive early in April, frequently before the lakes or large sloughs are free from ice, resorting to the wet prairies and stubble-fields; the great bulk are paired when they reach here and they soon commence nesting, their nests being made in all sorts of places. I have found them in the marshy sloughs on the open prairie, near water usually, and once in the bush at least a half a mile from a very small stream that always dried up during the summer, but which was the only water for a long distance.

About the middle of May the females commence to set; the drakes then molt, losing their brilliant plumage; whilst undergoing this change they gather together into small flocks of about five or six and hide themselves in the rushes, from which it is very hard to dislodge them even with good dogs.

In September they gather into flocks, young and old together, and visit the wheat and barley stubbles, rapidly becoming fat; the drakes at this time begin to show the green feathers on their heads, and by the time they leave they have acquired their perfect plumage.

A few frequently remain for some little time after the snow has covered the ground; these I have seen feeding around the base of the stacks and resorting to Lake Manitoba for water; in 1885 they were abundant up to November 9, but left on the day, after, for on the 11th I saw the last of the season, a single bird only.

On the 15th of September, 1892, I shot a large drake, which had pure white pinion feathers and a broad band of white from the usual ring around the neck to the breast; this bird was with seven others, all of the usual color and size. (Nash, in MSS.)

Very rare summer resident. Winnipeg: Summer resident; rare; only two specimens in 10 years, one at Long Lake, one at Lake Winnipeg (Hine). Red River Valley: Very rare; Manitoba is their most western limit (Hunter). I have received a specimen and seen others from York Factory (Blakiston).

Rare summer resident; abundant throughout the region along the Boundary from Pembina to the Rockies; breeds (Coues). Winnipeg: Summer resident; tolerably common (Hine). Red River Valley: Summer resident; tolerably common at Lake Manitoba (Hunter). Breeding on Shoal Lake (D. Gunn). Only one specimen shot on the Assiniboine, September, 1881 (Macoun). Portage la Prairie: Rare; have shot a few in the autumn near Lake Manitoba (Nash). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; April 20 (Guernsey).

Tolerably common summer resident; abundant throughout the region along the boundary from Pembina to the Rockies; breeds (Coues). Dufferin: Arrived between April 20 and 25 (Dawson). Winnipeg: Summer resident; tolerably common (Hine). Selkirk Settlements: Breeding; Lake Winnipeg in the breeding season in considerable numbers (D. Gunn). Swampy Island: 1885, first seen, four, on May 10; next seen, May 11; bulk arrived May 12; is common, and breeds here; in fall, last seen, October 2; 1886, first four on May 10; bulk arrived on May 13 (Plunkett). A specimen from between Lake Winnipeg and Hudson Bay in Smithsonian Institution (Blakiston). Portage la Prairie: Abundant summer resident; breeding at Lake Manitoba and in all the sloughs in this vicinity; this is the last duck to arrive in the spring and the first to leave in the fall; in 1884, first seen, April 16 (Nash). Silver Creek: July 5, 1882, shot a Widgeon, female; apparently breeding; length, 18; extension, 33; gizzard full of shell-fish (Thompson). Shell River: 1885, first seen, a pair on May 12; next seen, four, on May 23; is common all summer, and breeds here (Calcutt). Frequent on the Assiniboine; 1881 (Macoun). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; April 20 (Guernsey).

Abundant migrant; many breeding; extremely abundant throughout the region along the boundary from Pembina to the Rockies in August; doubtless some breed (Coues). Dufferin: Arrived between 15th and 20th (Dawson). Winnipeg: Summer resident; abundant; breeding (Hine). Swampy Island: 1885, first seen, two, on May 3; next seen, the bulk, May 6; is tolerably common, and breeds here; in fall, last seen September 1; 1886, first seen five on May 8; bulk arrived May 10 (Plunkett). Very common near Norway House; scarce northward (Bell, 1880). Portage la Prairie: 1884, abundant migrant and common summer resident, arriving at about the same time as the Mallard, but leaving as soon as the sloughs are frozen over; I have found flappers as late as the 15th of August (Nash). Rarely found breeding on the plains; apparently goes further north; in immense flocks on the Assiniboine in the fall of 1881 (Macoun). Carberry: common; breeding; Silver Creek, Rapid City (Thompson). Dalton: 1889, first seen, two, on April 15; next seen on April 16, when it became common; does not breed here (Youmans). Brandon: April 20, 1882 (Wood). Shell River: 1885, first seen, a pair on May 2; afterward seen every day; is common all summer, and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds April 5 to 15 (Guernsey).

On June 29, 1882, at Rapid City, Dr. A. S. Thompson shot a Green-winged Teal with his rifle. Although shot through the belly it was not killed, but flew with its entrails trailing, and it required a charge of dust shot to finish it. It was a male; length, 15; extension, 23; gizzard full of shell fish. This species is very abundant throughout the whole of the pondy prairie region from here to Carberry. It is usually met with in pairs and is of a very affectionate disposition, for if one be shot the other either remains to share its fate, or if it does fly at first, usually returns almost immediately to the side of its mate. I found it an expert diver, for often one of them would disappear at the approach of the gunner and be seen no more; doubtless it had swam under water to the nearest reed-bed, in whose friendly shelter it was securely hiding.

On July 5, at Silver Creek, came across a female Green-winged Teal traveling with her brood of ten young ones across the prairie towards a large pool. The mother bird was in great grief on finding that she was discovered, but she would not fly away; she threw herself on the ground at my feet and beat with her wings as though quite unable to escape and tried her utmost to lead me away. But I was familiar with the trick and would not be beguiled. I caught most of the tiny yellow downlings before they could hide and carried them carefully to the pool, where soon afterward the trembling mother rejoined them in safety.

This species, I think, unlike the blue-wing, usually nests quite close to the water, so that it was probably owing to the drying up of the pond that this newly hatched brood found themselves forced to take an overland journey of considerable extent before they could find a sufficiency of water.

Very abundant; summer resident; general distribution in the prairie regions; along the boundary, Mouse River, in fore part of August becomes very abundant; doubtless breeds (Coues). Winnipeg: Summer resident; abundant; breeding (Hine). Sparingly at Shoal Lake and Lake Winnipeg (Brewer). Swamp Island: 1885; breeds here; last seen August 26 (Plunkett). Shoal Lake, May 19, 1887 (Christy). Portage la Prairie: Very abundant; summer resident, and like the mallard nesting wherever it takes a fancy to do so; in 1884 first seen April 16 (Nash). Breeds abundantly around marshy ponds in the prairie country; exceedingly abundant in fall of 1880; rare in Assiniboine in September, 1881 (Macoun). Carberry: Common; breeding; Souris Plains, Turtle Mountain, Long River, Rapid City, and the whole south slope of Riding Mountain (Thompson). Dalton: 1889, first seen, one on April 18; next seen, May 15, when it became common; breeds here (Youmans). Shell River; 1885, first seen, a pair on May 2, afterwards every day; is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds May 10 (Guernsey).

I have frequently remarked that during the breeding season this species may be seen coursing over and around the ponds in threes, and these when shot usually prove a male and two females. After dark they may be identified during these maneuvers by their swift flight and the peculiar chirping, almost a twittering, that they indulge in as they fly.

On August 19, 1882, at Markle’s Lake, shot a Blue-winged Teal. This sheet of water is not more than 3 acres; it has hard banks, almost entirely without rushes or other cover, and is a mile or more from the nearest pond. This duck is very abundant in the country, and I think it usually nests much farther from the water than any of its near congeners. Like the Green-wing it is a good diver, but it is less wary and more easily shot; it seems to prefer the smaller ponds and leaves the large sheets to the Mallard and other large ducks.

Very rare; straggler; I have taken the Cinnamon Teal at Oak Lake, and I think also at Lake Manitoba, but during fifteen years’ residence in Manitoba I have only seen five or six specimens (R. H. Hunter).

Abundant summer resident, of general distribution; abundant throughout the region along the boundary from Pembina to the Rockies; breeding on Mouse River (Coues). Dufferin: Arrived between April 20 and 25 (Dawson). Winnipeg: Summer resident; abundant (Hine). Breeding at Red River, Shoal Lake, and Lake Winnipeg (Brewer). Swampy Island: 1886, first seen, six, on May 28; abundant summer resident (Plunkett). On Lake Winnipeg, the young were nearly full grown in the beginning of July (Bell, 1880). Shoal Lake: Breeding May 17, 1887 (Christy). Portage la Prairie: 1884, common summer resident; breeds in most of the sloughs near here; I have only once seen anything like a flock of these birds, and then there were not more than a dozen of them; they arrive late and depart as soon as the shallow waters they frequent are frozen; in 1884, first seen April 16 (Nash). Observed great numbers in August on the prairie ponds about Pleasant Hills; breeding on ponds throughout the prairie, but more abundantly throughout the copsewood region (Macoun). Brandon, Pembina, and Rapid City: Breeding (Thompson). Dalton: 1889, first seen, one on April 16; is common, and breeds here (Youmans). Shell River: 1885, first seen, a pair on May 8; next seen, four on May 22; is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; May 1 (Guernsey). Trout Lake (Murray).

Common summer resident of general distribution; abundant throughout the region along the boundary westward from Pembina, in summer as well as in fall (Coues). Dufferin: Arrived between April 15 and 20 (Dawson). Winnipeg: Summer resident; abundant (Hine). Red River to Hudson’s Bay (Blakiston). Breeds near Norway House (Bell, 1880). Osowa: Common; breeding; 1885, first seen, one on April 7, next seen April 16; became common April 20; last seen, thirteen, on November 1 (Wagner). Portage la Prairie: Abundant; summer resident; first seen in 1884, April 16; arriving early, generally with the Mallard, but leaving much earlier, the first frost driving them out (Nash). Carberry: Tolerably common summer resident; breeding; Souris Plain, Turtle Mountain, Fingerboard, near Rapid City (Thompson). Dalton: 1889, first seen, about ten, on March 21; seen every day afterwards; became common on March 23; breeds here (Youmans). Brandon: April 9, 1882 (Wood). Breeding on the prairies south of Pipestone Creek (Macoun). Shell River: 1885, first seen, four, on April 20, afterwards seen every day, male and female; is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds April 5 to 15 (Guernsey). Trout Lake Station and Severn House (Murray).

Rare summer resident; several small flocks in latter part of September, north of Red River, in Minnesota, feeding on wild rice (Kennicott). Rat Portage: October 10, 1886, found the head of a male Wood Duck lying on the shore (Thompson). Winnipeg: Summer resident; rare (Hine). I have seen the Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) at Westbourne, and it is always to be found along Cook’s Creek, east of Winnipeg (Hunter). Portage la Prairie: A rare and local summer resident, but I think increasing; previous to September 21, 1884, I never saw any in this neighborhood, though I had heard that a few pairs always bred on the White Mud River, near Westbourne, on that day; I saw two on the Assiniboine the following year; two or three broods were raised here, out of which, in September, I shot several, and on the 9th of October I killed one of the handsomest drakes I have ever seen; its plumage was simply perfect (Nash). Observed on Lake Winnepegosis by Mr. Tyrrell (Macoun). Carberry: A single pair taken in 1883 (Thompson). Qu’Appelle: I know of one being shot here in five years (Guernsey). A male killed at Cumberland House, June, 1827 (Richardson). Mr. Hine, of Winnipeg, showed me some fine specimens taken at Lake Winnipeg; he described it as regular, though not common, in the mouths of such creeks as flow through the heavy timber into Lake Winnipeg; Devils’ Creek is a favorite place, and here they are found feeding largely on the wild potato which grows on the overhanging banks, so that the bird may gather it without leaving the water; Hudson’s Bay; Moose Factory; Trout Lake Station (Murray).

Common summer resident; breeding abundantly throughout the region along the boundary from Pembina to the Rockies (Coues). Swamp Island: Breeds here; last seen September 11 (Plunkett). Winnepeg; summer resident; abundant (Hine). Breeding at Oak Point Lake, Manitoba, Shoal Lake, and Selkirk Settlement (D. Gunn). Portage la Prairie: Abundant; summer resident; breeding in all the lakes and large sloughs; I have frequently shot flappers on the 15th of August; they arrive as soon as the rivers are open and stay until no open water is left; in 1884, first seen April 16 (Nash). Breeds abundantly on the marshes of Waterhen River (Macoun). Carberry: Tolerably common; summer resident; breeding (Thompson). Shell River: 1885, first seen, a pair on May 3, afterwards seen every day; is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; April 23 (Guernsey).

Oak Point. We procured some duck nests and among them were two Aythya americana, (Red-head ducks’ nests), one containing eight eggs, the other nineteen. When I was there in 1865 we found one belonging to the same kind of duck containing nineteen or twenty eggs. The Indians accuse this duck of dishonesty, stating it to have very little respect for the rights of property, being inclined to rob other ducks of their eggs and place them in its own nest. This species and the canvas-back are both found at Shoal Lake and at Manitoba, but nowhere in great numbers. (D. Gunn.)

Uncommon; a few breed; at Turtle Mountain in July (at the boundary) I saw several broods of partly grown young; in most of the region, however, the bird is less numerous than the Red-head (Coues). Winnipeg: Fairly common on Lake Manitoba, but not generally breeding (Hine). Red River Valley: Transient visitant; rare (Hunter). Oak Point and Shoal Lake: breeding (Gunn). Swampy Islands: 1885, first seen, sixty, on May 19; next seen, May 20; last seen May 25; does not breed here; is very abundant in fall and spring amongst open places in ice on lake (Plunkett). Portage la Prairie: 1884, first seen April 16; common in spring, particularly if the lowlands should be flooded; in 1882, during the spring freshet they were abundant, in the autumn; they are less frequently seen; some, however, breed on Lake Manitoba, for on the 18th of September, 1886, I saw four young birds in a game dealer’s shop in Winnipeg, the proprietor of which told me he had just received them from there, and a friend who knows the birds well also informed me that he had shot them on the same lake when they could scarcely fly (Nash). Qu’Appelle: Common migrant; April 23 (Guernsey).

I am positive that the canvas-back never breeds in Manitoba. I have shot in the spring every year for the past fifteen years, and have not seen ten canvas-back ducks during that time. I have occasionally shot them in the autumn, in the proportion of one canvas-back to two hundred other ducks. (Rich H. Hunter, in MSS., May, 1885.)

Common migrant; a few breed. Dufferin: Arrived between April 25 and 30 (Dawson). Specimen in Smithsonian Institution, from Red River Settlement (Blakiston). Winnepeg: Abundant (Hine). Red River Valley: Abundant migrants, but I can not concur that it commonly breeds in Manitoba (Hunter). Breeding at Lake Winnipeg (D. Gunn). A few breeding in Lake Winnipegosis, June, 1881 (Macoun). Portage la Prairie: Fall migrant; common in spring, arriving as soon as the rivers are open; not so frequently obtained in the autumn, principally, I think, because it confines itself to the large lakes, seldom visiting the creeks or sloughs at that season; it remains until it is frozen out; in 1884, first seen April 16 (Nash, in MSS.).

Carberry: Abundant; migrant (Thompson). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; arrives April 20 in flocks, with lesser Blue-bills and Ring-neck (Guernsey).

Abundant summer resident, of general distribution. Winnipeg: Abundant; breeding (Hine). Red River Valley: Abundant, chiefly in autumn; not commonly breeding (Hunter). Swamp Island: 1885, first seen, four, on May 12; next seen May 13, when it becomes common; is abundant and breeds here; 1886, first seen, two, on May 5; bulk arrived on May 11 (Plunkett). Shoal Lake: May 19, 1887 (Christy). Portage la Prairie: Abundant summer resident; breeding on all the prairie sloughs of any size; it arrives as soon as there is any open water, and remains so long as there is a hole in the ice big enough to hold it; in 1884, first seen April 16 (Nash). Breeding more commonly than the preceding (1881) (Macoun). Carberry: Abundant summer resident; breeding; Brandon, Souris Plain, south slope of Riding Mountain (Thompson). Shell River: 1885, first seen, two pair, on May 1; afterwards seen every day; it is common all summer and breeds here (Calcutt). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; arrives April 20 (Guernsey). Severn House (Murray).

Tolerably common summer resident. Winnipeg: Summer resident; common (Hine). Swamp Island: 1885, first seen, six, on May 9; next seen, the bulk, on May 10; tolerably common; breeds here (Plunkett). Breeding in the marshes of Waterhen River, 1881 (Macoun). Portage la Prairie: Common summer resident; frequently confounded with the last, and they are both frequently more than confounded by persons who shoot them, for if there is only one kick left in them when they drop they will utilize that to such good purpose that they will get under cover beneath the water, where they conceal themselves so well that it is almost useless to try to retrieve them (Nash). Qu’Appelle: Common summer resident; breeds; arrives April 20 (Guernsey).