* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10 (Oct 1946-Apr 1949) (Vol. 1)

Date of first publication: 1949

Author: anonymous

Date first posted: June 4, 2017

Date last updated: June 4, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170609

This ebook was produced by: Larry Harrison, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

TRIALS

OF

WAR CRIMINALS

BEFORE THE

NUERNBERG MILITARY TRIBUNALS

UNDER

CONTROL COUNCIL LAW No. 10

VOLUME I

NUERNBERG

OCTOBER 1946-APRIL 1949

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington 25, D. C. — Price $2.75 (Buckram)

In April 1949, judgment was rendered in the last of the series of 12 Nuernberg war crimes trials which had begun in October 1946 and were held pursuant to Allied Control Council Law No. 10. Far from being of concern solely to lawyers, these trials are of especial interest to soldiers, historians, students of international affairs, and others. The defendants in these proceedings, charged with war crimes and other offenses against international penal law, were prominent figures in Hitler’s Germany and included such outstanding diplomats and politicians as the State Secretary of the Foreign Office, von Weizsaecker, and cabinet ministers von Krosigk and Lammers; military leaders such as Field Marshals von Leeb, List, and von Kuechler; SS leaders such as Ohlendorf, Pohl, and Hildebrandt; industrialists such as Flick, Alfried Krupp, and the directors of I. G. Farben; and leading professional men such as the famous physician Gerhard Rose, and the jurist and Acting Minister of Justice, Schlegelberger.

In view of the weight of the accusations and the far-flung activities of the defendants, and the extraordinary amount of official contemporaneous German documents introduced in evidence, the records of these trials constitute a major source of historical material covering many events of the fateful years 1933 (and even earlier) to 1945, in Germany and elsewhere in Europe.

The Nuernberg trials under Law No. 10 were carried out under the direct authority of the Allied Control Council, as manifested in that law, which authorized the establishment of the Tribunals. The judicial machinery for the trials, including the Military Tribunals and the Office, Chief of Counsel for War Crimes, was prescribed by Military Government Ordinance No. 7 and was part of the occupation administration for the American zone, the Office of Military Government (OMGUS). Law No. 10, Ordinance No. 7, and other basic jurisdictional or administrative documents are printed in full hereinafter.

The proceedings in these trials were conducted throughout in the German and English languages, and were recorded in full by stenographic notes, and by electrical sound recording of all oral proceedings. The 12 cases required over 1,200 days of court proceedings and the transcript of these proceedings exceeds 330,000 pages, exclusive of hundreds of document books, briefs, etc. Publication of all of this material, accordingly, was quite unfeasible. This series, however, contains the indictments, judgments, and other important portions of the record of the 12 cases, and it is believed that these materials give a fair picture of the trials, and as full and illuminating a picture as is possible within the space available. Copies of the entire record of the trials are available in the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and elsewhere.

In some cases, due to time limitations, errors of one sort or another have crept into the translations which were available to the Tribunal. In other cases the same document appears in different trials, or even at different parts of the same trial, with variations in translation. For the most part these inconsistencies have been allowed to remain and only such errors as might cause misunderstanding have been corrected.

Volume I and part of Volume II of this series are dedicated to the first of the twelve cases, United States vs. Karl Brandt, et al. (Case No. 1). This trial has become known as the Medical Case, because 20 of the 23 defendants were doctors, and the charges related principally to medical experimentation on human beings. The remainder of Volume II is devoted to the trial of former Field Marshal Erhard Milch, who was also charged with criminal responsibilities for medical experimentation on human beings (of which charge he was acquitted), and with responsibility for the deportation to forced labor of numerous civilians, in violation of the laws of war (of which charge he was convicted).

| Preface | iii | |||

| Trials of War Criminals before Nuernberg Military Tribunals | vii | |||

| Declaration on German Atrocities | viii | |||

| Executive Order 9547 | ix | |||

| London Agreement of 8 August 1945 | ix | |||

| Charter of The International Military Tribunal | xi | |||

| Control Council Law No. 10 | xvi | |||

| Executive Order 9679 | xx | |||

| General Orders Number 301, Hq. USFET, 24 October 1946 | xx | |||

| Military Government—Germany, United States Zone, Ordinance No. 7 | xxi | |||

| Military Government—Germany, Ordinance No. 11 | xxvi | |||

| Officials of the Office of the Secretary General | xxviii | |||

| “The Medical Case” | ||||

| Introduction | 3 | |||

| Order Constituting Tribunal I | 5 | |||

| Members of the Tribunal | 6 | |||

| Prosecution Counsel | 7 | |||

| Defense Counsel | 7 | |||

| I. Indictment | 8 | |||

| II. Arraignment | 18 | |||

| III. Statement of the Tribunal on the Order of Trial and Rules of Procedure, 9 December 1946 | 24 | |||

| IV. Opening Statement of the Prosecution by Brigadier General Telford Taylor, 9 December 1946 | 27 | |||

| V. Introductory Statement on the Presentation of Evidence Made by the Prosecution, 10 December 1946 | 75 | |||

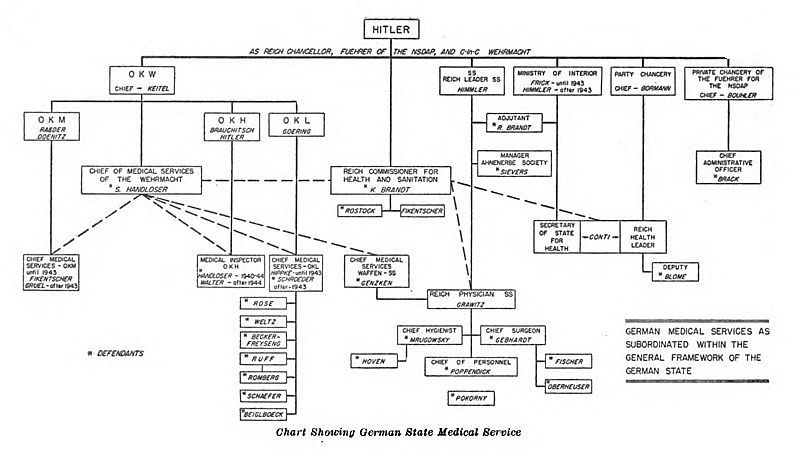

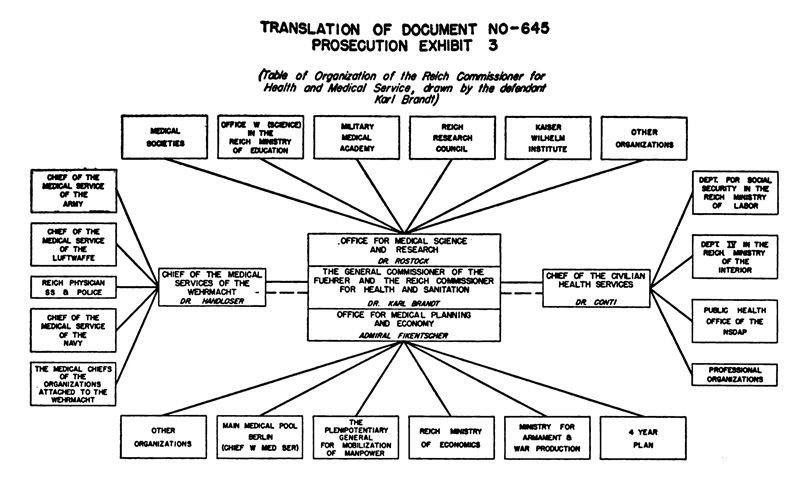

| VI. Organization of the German Medical Services | 81 | |||

| VII. Extracts from Argumentation and Evidence of Prosecution and Defense | 92 | |||

| A. Medical Experiments | 92 | |||

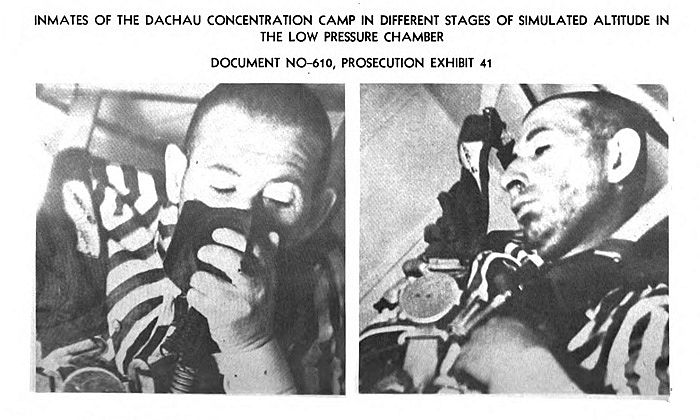

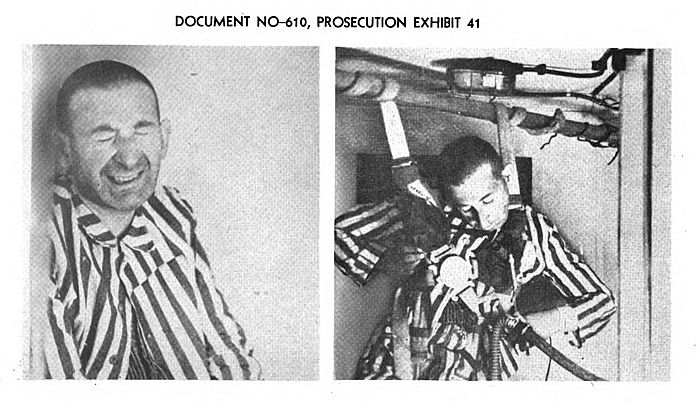

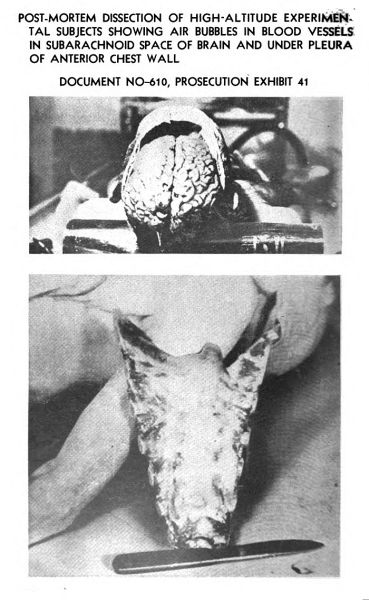

| 1. | High-altitude Experiments | 92 | ||

| 2. | Freezing Experiments | 198 | ||

| 3. | Malaria Experiments | 278 | ||

| 4. | Lost (Mustard) Gas Experiments | 314 | ||

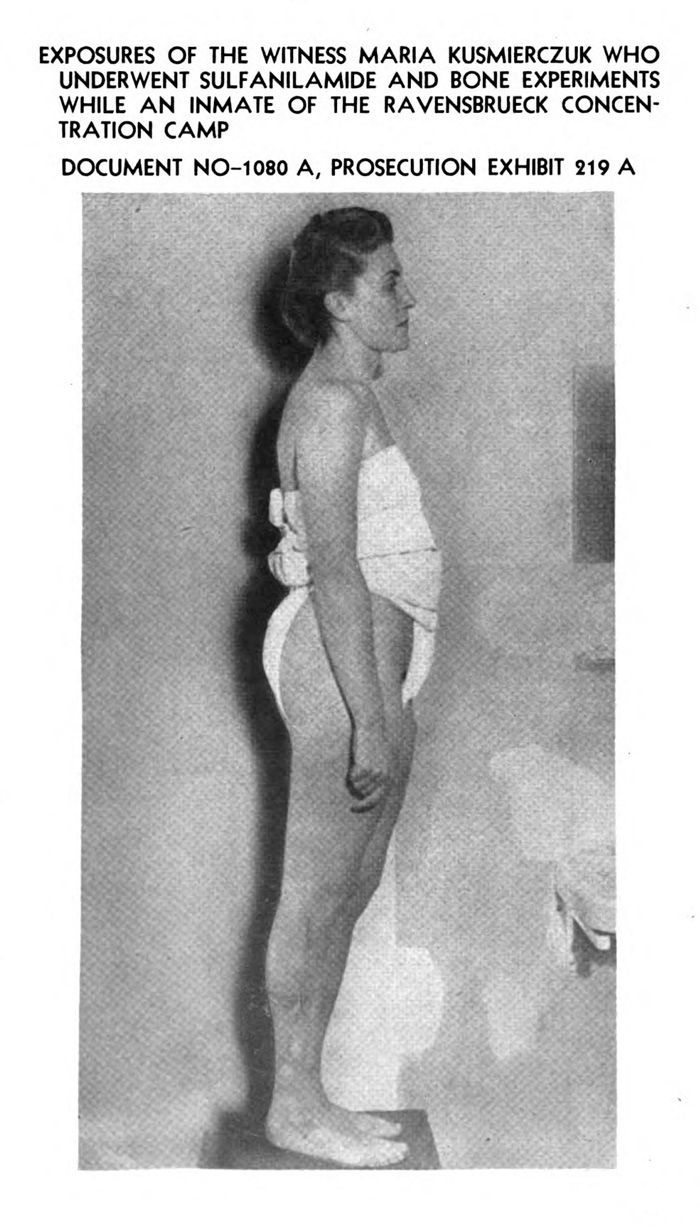

| 5. | Sulfanilamide Experiments | 354 | ||

| 6. | Bone, Muscle and Nerve Regeneration, and Bone Transplantation Experiments | 391 | ||

| 7. | Sea-water Experiments | 418 | ||

| 8. | Epidemic Jaundice Experiments | 494 | ||

| 9. | Typhus and Other Vaccine Experiments | 508 | ||

| 10. | Experiments with Poison | 631 | ||

| 11. | Incendiary Bomb Experiments | 639 | ||

| 12. | Phlegmon Experiments | 653 | ||

| 13. | Polygal Experiments | 669 | ||

| 14. | Gas Oedema (Phenol) Experiments | 684 | ||

| 15. | Experiments for Mass Sterilization | 694 | ||

| B. Jewish Skeleton Collection | 738 | |||

| C. Project to kill Tubercular Polish Nationals | 759 | |||

| D. Euthanasia | 794 | |||

| E. Selections from Photographic Evidence of the Prosecution | 897 | |||

| VIII. Evidence and Arguments on Important Aspects of the Case | 909 | |||

| A. Applicability of Control Council Law No. 10, to offenses against Germans During the War | 909 | |||

| B. Responsibility of Superiors for Acts of Subordinates | 925 | |||

| C. Responsibility of Subordinates for Acts Carried Out under Superior Orders | 957 | |||

| D. Status of Occupied Poland under International Law | 974 | |||

| E. Voluntary Participation of Experimental Subjects | 980 | |||

| (Sec. VIII continued in Vol. II) | ||||

| Volume II | ||||

| VIII. Evidence and Arguments on Important Aspects of the Case | ||||

| F. Necessity | ||||

| G. Subjection to Medical Experimentation as Substitute for Penalties | ||||

| H. Usefulness of the Experiments | ||||

| I. Medical Ethics | ||||

| 1. | General | |||

| 2. | German Medical Profession | |||

| 3. | Medical Experiments in other Countries | |||

| IX. Ruling of the Tribunal on Count One of the Indictment | ||||

| X. Final Plea for Defendant Karl Brandt by Dr. Servatius | ||||

| XI. Final Statements of the Defendants, 19 July 1947 | ||||

| XII. Judgment | ||||

| Sentences | ||||

| XIII. Petitions | ||||

| XIV. Affirmation of Sentences by the Commander of the U. S. Zone of Occupation | ||||

| XV. Supreme Court of the United States Denial of Writs of Habeas Corpus | ||||

| Appendix | ||||

| Table of Comparative Ranks | ||||

| List of Witnesses in Case I | ||||

| Index | ||||

| Case | |||

| No. | United States against | Popular Name | Volume No. |

| 1 | Karl Brandt, et al. | Medical Case | I and II |

| 2 | Erhard Milch | Milch Case | II |

| 3 | Josef Altstoetter, et al. | Justice Case | III |

| 4 | Oswald Pohl, et al. | Pohl Case | V |

| 5 | Friedrich Flick, et al. | Flick Case | VI |

| 6 | Carl Krauch, et al. | I. G. Farben Case | VII and VIII |

| 7 | Wilhelm List, et al. | Hostage Case | XI |

| 8 | Ulrich Greifelt, et al. | RuSHA Case | IV and V |

| 9 | Otto Ohlendorf, et al. | Einsatzgruppen Case | IV |

| 10 | Alfred Krupp, et al. | Krupp Case | IX |

| 11 | Ernst von Weizsaecker, et al. | Ministries Case | XII, XIII, and XIV |

| 12 | Wilhelm von Leeb, et al. | High Command Case | X and XI |

| Procedure | XV | ||

[Moscow Declaration]

Released November 1, 1943

THE UNITED KINGDOM, the United States and the Soviet Union have received from many quarters evidence of atrocities, massacres and cold-blooded mass executions which are being perpetrated by the Hitlerite forces in the many countries they have overrun and from which they are now being steadily expelled. The brutalities of Hitlerite domination are no new thing and all the peoples or territories in their grip have suffered from the worst form of government by terror. What is new is that many of these territories are now being redeemed by the advancing armies of the liberating Powers and that in their desperation, the recoiling Hitlerite Huns are redoubling their ruthless cruelties. This is now evidenced with particular clearness by monstrous crimes of the Hitlerites on the territory of the Soviet Union which is being liberated from the Hitlerites, and on French and Italian territory.

Accordingly, the aforesaid three allied Powers, speaking in the interests of the thirty-two [thirty-three] United Nations, hereby solemnly declare and give full warning of their declaration as follows:

At the time of the granting of any armistice to any government which may be set up in Germany, those German officers and men and members of the Nazi party who have been responsible for, or have taken a consenting part in the above atrocities, massacres, and executions, will be sent back to the countries in which their abominable deeds were done in order that they may be judged and punished according to the laws of these liberated countries and of the free governments which will be created therein. Lists will be compiled in all possible detail from all these countries having regard especially to the invaded parts of the Soviet Union, to Poland and Czechoslovakia, to Yugoslavia and Greece, including Crete and other islands, to Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, France and Italy.

Thus, the Germans who take part in wholesale shootings of Italian officers or in the execution of French, Dutch, Belgian, or Norwegian hostages or of Cretan peasants, or who have shared in the slaughters inflicted on the people of Poland or in territories of the Soviet Union which are now being swept clear of the enemy, will know that they will be brought back to the scene of their crimes and judged on the spot by the peoples whom they have outraged. Let those who have hitherto not imbrued their hands with innocent blood beware lest they join the ranks of the guilty, for most assuredly the three allied Powers will pursue them to the uttermost ends of the earth and will deliver them to their accusers in order that justice may be done.

The above declaration is without prejudice to the case of the major criminals, whose offences have no particular geographical localisation and who will be punished by the joint decision of the Governments of the Allies.

| [Signed] | ||

| Roosevelt | ||

| Churchill | ||

| Stalin |

Providing for Representation of the United States in Preparing and Prosecuting Charges of Atrocities and War Crimes Against the Leaders of the European Axis Powers and Their Principal Agents and Accessories

By virtue of the authority vested in me as President and as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, under the Constitution and statutes of the United States, it is ordered as follows:

1. Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson is hereby designated to act as the Representative of the United States and as its Chief of Counsel in preparing and prosecuting charges of atrocities and war crimes against such of the leaders of the European Axis powers and their principal agents and accessories as the United States may agree with any of the United Nations to bring to trial before an international military tribunal. He shall serve without additional compensation but shall receive such allowance for expenses as may be authorized by the President.

2. The Representative named herein is authorized to select and recommend to the President or to the head of any executive department, independent establishment, or other federal agency necessary personnel to assist in the performance of his duties hereunder. The head of each executive department, independent establishment, and other federal agency is hereby authorized to assist the Representative named herein in the performance of his duties hereunder and to employ such personnel and make such expenditures, within the limits of appropriations now or hereafter available for the purpose, as the Representative named herein may deem necessary to accomplish the purposes of this order, and may make available, assign, or detail for duty with the Representative named herein such members of the armed forces and other personnel as may be requested for such purposes.

3. The Representative named herein is authorized to cooperate with, and receive the assistance of, any foreign Government to the extent deemed necessary by him to accomplish the purposes of this order.

Harry S. Truman

The White House,

May 2, 1945.

(F. R. Doc. 45-7256; Filed, May 3, 1945; 10:57 a. m.)

AGREEMENT by the Government of the United States of America, the Provisional Government of the French Republic, the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis

Whereas the United Nations have from time to time made declarations of their intention that War Criminals shall be brought to justice;

And whereas the Moscow Declaration of the 30th October 1943 on German atrocities in Occupied Europe stated that those German Officers and men and members of the Nazi Party who have been responsible for or have taken a consenting part in atrocities and crimes will be sent back to the countries in which their abominable deeds were done in order that they may be judged and punished according to the laws of these liberated countries and of the free Governments that will be created therein;

And whereas this Declaration was stated to be without prejudice to the case of major criminals whose offenses have no particular geographical location and who will be punished by the Joint decision of the Governments of the Allies;

Now therefore the Government of the United States of America, the Provisional Government of the French Republic, the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (hereinafter called “the Signatories”) acting in the interests of all the United Nations and by their representatives duly authorized thereto have concluded this Agreement.

Article 1. There shall be established after consultation with the Control Council for Germany an International Military Tribunal for the trial of war criminals whose offenses have no particular geographical location whether they be accused individually or in their capacity as members of organizations or groups or in both capacities.

Article 2. The constitution, jurisdiction and functions of the International Military Tribunal shall be those set out in the Charter annexed to this Agreement, which Charter shall form an integral part of this Agreement.

Article 3. Each of the Signatories shall take the necessary steps to make available for the investigation of the charges and trial the major war criminals detained by them who are to be tried by the International Military Tribunal. The Signatories shall also use their best endeavors to make available for investigation of the charges against and the trial before the International Military Tribunal such of the major war criminals as are not in the territories of any of the Signatories.

Article 4. Nothing in this Agreement shall prejudice the provisions established by the Moscow Declaration concerning the return of war criminals to the countries where they committed their crimes.

Article 5. Any Government of the United Nations may adhere to this Agreement by notice given through the diplomatic channel to the Government of the United Kingdom, who shall inform the other signatory and adhering Governments of each such adherence.

Article 6. Nothing in this Agreement shall prejudice the jurisdiction or the powers of any national or occupation court established or to be established in any allied territory or in Germany for the trial of war criminals.

Article 7. This agreement shall come into force on the day of signature and shall remain in force for the period of one year and shall continue thereafter, subject to the right of any Signatory to give, through the diplomatic channel, one month’s notice of intention to terminate it. Such termination shall not prejudice any proceedings already taken or any findings already made in pursuance of this Agreement.

In witness whereof the Undersigned have signed the present Agreement.

Done in quadruplicate in London this 8th day of August 1945 each in English, French and Russian, and each text to have equal authenticity.

For the Government of the United States of America

Robert H. Jackson

For the Provisional Government of the French Republic

Robert Falco

For the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Jowitt, C.

For the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

I. Nikitchenko

A. Trainin

Article 1. In pursuance of the Agreement signed on the 8th day of August 1945 by the Government of the United States of America, the Provisional Government of the French Republic, the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, there shall be established an International Military Tribunal (hereinafter called “the Tribunal”) for the just and prompt trial and punishment of the major war criminals of the European Axis.

Article 2. The Tribunal shall consist of four members, each with an alternate. One member and one alternate shall be appointed by each of the Signatories. The alternates shall, so far as they are able, be present at all sessions of the Tribunal. In case of illness of any member of the Tribunal or his incapacity for some other reason to fulfill his functions, his alternate shall take his place.

Article 3. Neither the Tribunal, its members nor their alternates can be challenged by the prosecution, or by the Defendants or their Counsel. Each Signatory may replace its member of the Tribunal or his alternate for reasons of health or for other good reasons, except that no replacement may take place during a Trial, other than by an alternate.

Article 4.

(a) The presence of all four members of the Tribunal or the alternate for any absent member shall be necessary to constitute the quorum.

(b) The members of the Tribunal shall, before any trial begins, agree among themselves upon the selection from their number of a President, and the President shall hold office during that trial, or as may otherwise be agreed by a vote of not less than three members. The principle of rotation of presidency for successive trials is agreed. If, however, a session of the Tribunal takes place on the territory of one of the four Signatories, the representative of that Signatory on the Tribunal shall preside.

(c) Save as aforesaid the Tribunal shall take decisions by a majority vote and in case the votes are evenly divided, the vote of the President shall be decisive: provided always that convictions and sentences shall only be imposed by affirmative votes of at least three members of the Tribunal.

Article 5. In case of need and depending on the number of the matters to be tried, other Tribunals may be set up; and the establishment, functions, and procedure of each Tribunal shall be identical, and shall be governed by this Charter.

Article 6. The Tribunal established by the Agreement referred to in Article 1 hereof for the trial and punishment of the major war criminals of the European Axis countries shall have the power to try and punish persons who, acting in the interests of the European Axis countries, whether as individuals or as members of organizations, committed any of the following crimes.

The following acts, or any of them, are crimes coming within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal for which there shall be individual responsibility:

(a) CRIMES AGAINST PEACE: namely, planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression, or a war in violation of International treaties, agreements or assurances, or participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of any of the foregoing;

(b) WAR CRIMES: namely, violations of the laws or customs of war. Such violations shall include, but not be limited to, murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave labor or for any other purpose of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war or persons on the seas, killing of hostages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity;

(c) CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY: namely, murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war; or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated.[1]

Leaders, organizers, instigators and accomplices participating in the formulation or execution of a common plan or conspiracy to commit any of the foregoing crimes are responsible for all acts performed by any persons in execution of such plan.

Article 7. The official position of defendants, whether as Heads of State or responsible officials in Government Departments, shall not be considered as freeing them from responsibility or mitigating punishment.

Article 8. The fact that the Defendant acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior shall not free him from responsibility, but may be considered in mitigation of punishment if the Tribunal determines that justice so requires.

Article 9. At the trial of any individual member of any group or organization the Tribunal may declare (in connection with any act of which the individual may be convicted) that the group or organization of which the individual was a member was a criminal organization.

After receipt of the Indictment the Tribunal shall give such notice as it thinks fit that the prosecution intends to ask the Tribunal to make such declaration and any member of the organization will be entitled to apply to the Tribunal for leave to be heard by the Tribunal upon the question of the criminal character of the organization. The Tribunal shall have power to allow or reject the application. If the application is allowed, the Tribunal may direct in what manner the applicants shall be represented and heard.

Article 10. In cases where a group or organization is declared criminal by the Tribunal, the competent national authority of any Signatory shall have the right to bring individuals to trial for membership therein before national, military or occupation courts. In any such case the criminal nature of the group or organization is considered proved and shall not be questioned.

Article 11. Any person convicted by the Tribunal may be charged before a national, military or occupation court, referred to in Article 10 of this Charter, with a crime other than of membership in a criminal group or organization and such court may, after convicting him, impose upon him punishment independent of and additional to the punishment imposed by the Tribunal for participation in the criminal activities of such group or organization.

Article 12. The Tribunal shall have the right to take proceedings against a person charged with crimes set out in Article 6 of this Charter in his absence, if he has not been found or if the Tribunal, for any reason, finds it necessary, in the interests of justice, to conduct the hearing in his absence.

Article 13. The Tribunal shall draw up rules for its procedure. These rules shall not be inconsistent with the provisions of this Charter.

Article 14. Each Signatory shall appoint a Chief Prosecutor for the investigation of the charges against and the prosecution of major war criminals.

The Chief Prosecutors shall act as a committee for the following purposes:

(a) to agree upon a plan of the individual work of each of the Chief Prosecutors and his staff,

(b) to settle the final designation of major war criminals to be tried by the Tribunal,

(c) to improve the Indictment and the documents to be submitted therewith,

(d) to lodge the Indictment and the accompanying documents with the Tribunal,

(e) to draw up and recommend to the Tribunal for its approval draft rules of procedure, contemplated by Article 13 of this Charter. The Tribunal shall have power to accept, with or without amendments, or to reject, the rules so recommended.

The Committee shall act in all the above matters by a majority vote and shall appoint a Chairman as may be convenient and in accordance with the principle of rotation: provided that if there is an equal division of vote concerning the designation of a Defendant to be tried by the Tribunal, or the crimes with which he shall be charged, that proposal will be adopted which was made by the party which proposed that the particular Defendant be tried, or the particular charges be preferred against him.

Article 15. The Chief Prosecutors shall individually, and acting in collaboration with one another, also undertake the following duties:

(a) investigation, collection, and production before or at the Trial of all necessary evidence,

(b) the preparation of the Indictment for approval by the Committee in accordance with paragraph (c) of Article 14 hereof,

(c) the preliminary examination of all necessary witnesses and of the Defendants,

(d) to act as prosecutor at the Trial,

(e) to appoint representatives to carry out such duties as may be assigned to them,

(f) to undertake such other matters as may appear necessary to them for the purposes of the preparation for and conduct of the Trial.

It is understood that no witness or Defendant detained by any Signatory shall be taken out of the possession of that Signatory without its assent.

Article 16. In order to ensure fair trial for the Defendants, the following procedure shall be followed:

(a) The Indictment shall include full particulars specifying in detail the charges against the Defendants. A copy of the Indictment and of all the documents lodged with the Indictment, translated into a language which he understands, shall be furnished to the Defendant at a reasonable time before the Trial.

(b) During any preliminary examination or trial of a Defendant he shall have the right to give any explanation relevant to the charges made against him.

(c) A preliminary examination of a Defendant and his Trial shall be conducted in, or translated into, a language which the Defendant understands.

(d) A defendant shall have the right to conduct his own defense before the Tribunal or to have the assistance of Counsel.

(e) A defendant shall have the right through himself or through his Counsel to present evidence at the Trial in support of his defense, and to cross-examine any witness called by the Prosecution.

Article 17. The Tribunal shall have the power

(a) to summon witnesses to the Trial and to require their attendance and testimony and to put questions to them,

(b) to interrogate any Defendant,

(c) to require the production of documents and other evidentiary material,

(d) to administer oaths to witnesses,

(e) to appoint officers for the carrying out of any task designated by the Tribunal including the power to have evidence taken on commission.

Article 18. The Tribunal shall

(a) confine the Trial strictly to an expeditious hearing of the issues raised by the charges,

(b) take strict measures to prevent any action which will cause unreasonable delay, and rule out irrelevant issues and statements of any kind whatsoever,

(c) deal summarily with any contumacy, imposing appropriate punishment, including exclusion of any Defendant or his Counsel from some or all further proceedings, but without prejudice to the determination of the charges.

Article 19. The Tribunal shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence. It shall adopt and apply to the greatest possible extent expeditious and non-technical procedure, and shall admit any evidence which it deems to have probative value.

Article 20. The Tribunal may require to be informed of the nature of any evidence before it is offered so that it may rule upon the relevance thereof.

Article 21. The Tribunal shall not require proof of facts of common knowledge but shall take Judicial notice thereof. It shall also take judicial notice of official governmental documents and reports of the United Nations, including the acts and documents of the committees set up in the various allied countries for the investigation of war crimes, and the records and findings of military or other Tribunals of any of the United Nations.

Article 22. The permanent seat of the Tribunal shall be in Berlin. The first meetings of the members of the Tribunal and of the Chief Prosecutors shall be held at Berlin in a place to be designated by the Control Council for Germany. The first trial shall be held at Nuremberg, and any subsequent trials shall be held at such places as the Tribunal may decide.

Article 23. One or more of the Chief Prosecutors may take part in the prosecution at each Trial. The function of any Chief Prosecutor may be discharged by him personally, or by any person or persons authorized by him.

The function of Counsel for a Defendant may be discharged at the Defendant’s request by any Counsel professionally qualified to conduct cases before the Courts of his own country, or by any other person who may be specially authorized thereto by the Tribunal.

Article 24. The proceedings at the Trial shall take the following course:

(a) The Indictment shall be read in court.

(b) The Tribunal shall ask each Defendant whether he pleads “guilty” or “not guilty”.

(c) The Prosecution shall make an opening statement.

(d) The Tribunal shall ask the Prosecution and the Defense what evidence (if any) they wish to submit to the Tribunal, and the Tribunal shall rule upon the admissibility of any such evidence.

(e) The witnesses for the Prosecution shall be examined and after that the witnesses for the Defense. Thereafter such rebutting evidence as may be held by the Tribunal to be admissible shall be called by either the Prosecution or the Defense.

(f) The Tribunal may put any question to any witness and to any Defendant, at any time.

(g) The Prosecution and the Defense shall interrogate and may cross-examine any witnesses and any Defendant who gives testimony.

(h) The Defense shall address the court.

(i) The Prosecution shall address the court.

(j) Each Defendant may make a statement to the Tribunal.

(k) The Tribunal shall deliver judgment and pronounce sentence.

Article 25. All official documents shall be produced, and all court proceedings conducted, in English, French and Russian, and in the language of the Defendant. So much of the record and of the proceedings may also be translated into the language of any country in which the Tribunal is sitting, as the Tribunal considers desirable in the interests of justice and public opinion.

Article 26. The judgment of the Tribunal as to the guilt or the innocence of any Defendant shall give the reasons on which it is based, and shall be final and not subject to review.

Article 27. The Tribunal shall have the right to impose upon a Defendant, on conviction, death or such other punishment as shall be determined by it to be just.

Article 28. In addition to any punishment imposed by it, the Tribunal shall have the right to deprive the convicted person of any stolen property and order its delivery to the Control Council for Germany.

Article 29. In case of guilt, sentences shall be carried out in accordance with the orders of the Control Council for Germany, which may at any time reduce or otherwise alter the sentences, but may not increase the severity thereof. If the Control Council for Germany, after any Defendant has been convicted and sentenced, discovers fresh evidence which, in its opinion, would found a fresh charge against him, the Council shall report accordingly to the Committee established under Article 14 hereof, for such action as they may consider proper, having regard to the interests of justice.

Article 30. The expenses of the Tribunal and of the Trials, shall be charged by the Signatories against the funds allotted for maintenance of the Control Council for Germany.

Whereas an Agreement and Charter regarding the Prosecution of War Criminals was signed in London on the 8th August 1945, in the English, French, and Russian languages.

And whereas a discrepancy has been found to exist between the originals of Article 6, paragraph (c), of the Charter in the Russian language, on the one hand, and the originals in the English and French languages, on the other, to wit, the semi-colon in Article 6, paragraph (c), of the Charter between the words “war” and “or”, as carried in the English and French texts, is a comma in the Russian text.

and whereas it is desired to rectify this discrepancy:

Now, therefore, the undersigned, signatories of the said Agreement on behalf of their respective Governments, duly authorized thereto, have agreed that Article 6, paragraph (c), of the Charter in the Russian text is correct, and that the meaning and intention of the Agreement and Charter require that the said semi-colon in the English text should be changed to a comma, and that the French text should be amended to read as follows:

(c) Les Crimes Contre L’Humanite: c’est à dire l’assassinat, l’extermination, la réduction en esclavage, la déportation, et tout autre acte inhumain commis contre toutes populations civiles, avant ou pendant la guerre, ou bien les persécutions pour des motifs politiques, raciaux, ou réligieux, lorsque ces actes ou persécutions, qu’ils aient constitué ou non une violation du droit interne du pays où ils ont été perpétrés, ont été commis à la suite de tout crime rentrant dans la compétence du Tribunal, ou en liaison avec ce crime.

In witness whereof the Undersigned have signed the present Protocol.

Done in quadruplicate in Berlin this 6th day of October, 1945, each in English, French, and Russian, and each text to have equal authenticity.

For the Government of the United States of America

Robert H. Jackson

For the Provisional Government of the French Republic

François de Menthon

For the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Hartley Shawcross

For the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

R. Rudenko

[1] See proctocol p. XV for correction of this paragraph.

In order to give effect to the terms of the Moscow Declaration of 30 October 1943 and the London Agreement of 8 August 1945, and the Charter issued pursuant thereto and in order to establish a uniform legal basis in Germany for the prosecution of war criminals and other similar offenders, other than those dealt with by the International Military Tribunal, the Control Council enacts as follows:

The Moscow Declaration of 30 October 1943 “Concerning Responsibility of Hitlerites for Committed Atrocities” and the London Agreement of 8 August 1945 “Concerning Prosecution and Punishment of Major War Criminals of the European Axis” are made integral parts of this Law. Adherence to the provisions of the London Agreement by any of the United Nations, as provided for in Article V of that Agreement, shall not entitle such Nation to participate or interfere in the operation of this Law within the Control Council area of authority in Germany.

1. Each of the following acts is recognized as a crime:

(a) Crimes against Peace. Initiation of invasions of other countries and wars of aggression in violation of international laws and treaties, including but not limited to planning, preparation, initiation or waging a war of aggression, or a war of violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances, or participation in a common plan or conspiracy for the accomplishment of any of the foregoing.

(b) War Crimes. Atrocities or offences against persons or property constituting violations of the laws or customs of war, including but not limited to, murder, ill treatment or deportation to slave labour or for any other purpose, of civilian population from occupied territory, murder or ill treatment of prisoners of war or persons on the seas, killing of hostages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity.

(c) Crimes against Humanity. Atrocities and offences, including but not limited to murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, imprisonment, torture, rape, or other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds whether or not in violation of the domestic laws of the country where perpetrated.

(d) Membership in categories of a criminal group or organization declared criminal by the International Military Tribunal.

2. Any person without regard to nationality or the capacity in which he acted, is deemed to have committed a crime as defined in paragraph 1 of this Article, if he was (a) a principal or (b) was an accessory to the commission of any such crime or ordered or abetted the same or (c) took a consenting part therein or (d) was connected with plans or enterprises involving its commission or (e) was a member of any organization or group connected with the commission of any such crime or (f) with reference to paragraph 1 (a), if he held a high political, civil or military (including General Staff) position in Germany or in one of its Allies, co-belligerents or satellites or held high position in the financial, industrial or economic life of any such country.

3. Any person found guilty of any of the Crimes above mentioned may upon conviction be punished as shall be determined by the tribunal to be just. Such punishment may consist of one or more of the following:

(a) Death.

(b) Imprisonment for life or a term of years, with or without hard labour.

(c) Fine, and imprisonment with or without hard labour, in lieu, thereof.

(d) Forfeiture of property.

(e) Restitution of property wrongfully acquired.

(f) Deprivation of some or all civil rights.

Any property declared to be forfeited or the restitution of which is ordered by the Tribunal shall be delivered to the Control Council for Germany, which shall decide on its disposal.

4. (a) The official position of any person, whether as Head of State or as a responsible official in a Government Department, does not free him from responsibility for a crime or entitle him to mitigation of punishment.

(b) The fact that any person acted pursuant to the order of his Government or of a superior does not free him from responsibility for a crime, but may be considered in mitigation.

5. In any trial or prosecution for a crime herein referred to, the accused shall not be entitled to the benefits of any statute of limitation in respect of the period from 30 January 1933 to 1 July 1945, nor shall any immunity, pardon or amnesty granted under the Nazi regime be admitted as a bar to trial or punishment.

1. Each occupying authority, within its Zone of occupation,

(a) shall have the right to cause persons within such Zone suspected of having committed a crime, including those charged with crime by one of the United Nations, to be arrested and shall take under control the property, real and personal, owned or controlled by the said persons, pending decisions as to its eventual disposition.

(b) shall report to the Legal Directorate the names of all suspected criminals, the reasons for and the places of their detention, if they are detained, and the names and location of witnesses.

(c) shall take appropriate measures to see that witnesses and evidence will be available when required.

(d) shall have the right to cause all persons so arrested and charged, and not delivered to another authority as herein provided, or released, to be brought to trial before an appropriate tribunal. Such tribunal may, in the case of crimes committed by persons of German citizenship or nationality against other persons of German citizenship or nationality, or stateless persons, be a German Court, if authorized by the occupying authorities.

2. The tribunal by which persons charged with offenses hereunder shall be tried and the rules and procedure thereof shall be determined or designated by each Zone Commander for his respective Zone. Nothing herein is intended to, or shall impair or limit the jurisdiction or power of any court or tribunal now or hereafter established in any Zone by the Commander thereof, or of the International Military Tribunal established by the London Agreement of 8 August 1945.

3. Persons wanted for trial by an International Military Tribunal will not be tried without the consent of the Committee of Chief Prosecutors. Each Zone Commander will deliver such persons who are within his Zone to that committee upon request and will make witnesses and evidence available to it.

4. Persons known to be wanted for trial in another Zone or outside Germany will not be tried prior to decision under Article IV unless the fact of their apprehension has been reported in accordance with Section 1 (b) of this Article, three months have elapsed thereafter, and no request for delivery of the type contemplated by Article IV has been received by the Zone Commander concerned.

5. The execution of death sentences may be deferred by not to exceed one month after the sentence has become final when the Zone Commander concerned has reason to believe that the testimony of those under sentence would be of value in the investigation and trial of crimes within or without his Zone.

6. Each Zone Commander will cause such effect to be given to the judgments of courts of competent jurisdiction, with respect to the property taken under his control pursuant hereto, as he may deem proper in the interest of justice.

1. When any person in a Zone in Germany is alleged to have committed a crime, as defined in Article II, in a country other than Germany or in another Zone, the government of that nation or the Commander of the latter Zone, as the case may be, may request the Commander of the Zone in which the person is located for his arrest and delivery for trial to the country or Zone in which the crime was committed. Such request for delivery shall be granted by the Commander receiving it unless he believes such person is wanted for trial or as a witness by an International Military Tribunal, or in Germany, or in a nation other than the one making the request, or the Commander is not satisfied that delivery should be made, in any of which cases he shall have the right to forward the said request to the Legal Directorate of the Allied Control Authority. A similar procedure shall apply to witnesses, material exhibits and other forms of evidence.

2. The Legal Directorate shall consider all requests referred to it, and shall determine the same in accordance with the following principles, its determination to be communicated to the Zone Commander.

(a) A person wanted for trial or as a witness by an International Military Tribunal shall not be delivered for trial or required to give evidence outside Germany, as the case may be, except upon approval of the Committee of Chief Prosecutors acting under the London Agreement of 8 August 1945.

(b) A person wanted for trial by several authorities (other than an International Military Tribunal) shall be disposed of in accordance with the following priorities:

(1) If wanted for trial in the Zone in which he is, he should not be delivered unless arrangements are made for his return after trial elsewhere;

(2) If wanted for trial in a Zone other than that in which he is, he should be delivered to that Zone in preference to delivery outside Germany unless arrangements are made for his return to that Zone after trial elsewhere;

(3) If wanted for trial outside Germany by two or more of the United Nations, of one of which he is a citizen, that one should have priority;

(4) If wanted for trial outside Germany by several countries, not all of which are United Nations, United Nations should have priority;

(5) If wanted for trial outside Germany by two or more of the United Nations, then, subject to Article IV 2 (b) (3) above, that which has the most serious charges against him, which are moreover supported by evidence, should have priority.

The delivery, under Article IV of this Law, of persons for trial shall be made on demands of the Governments or Zone Commanders in such a manner that the delivery of criminals to one jurisdiction will not become the means of defeating or unnecessarily delaying the carrying out of justice in another place. If within six months the delivered person has not been convicted by the Court of the zone or country to which he has been delivered, then such person shall be returned upon demand of the Commander of the Zone where the person was located prior to delivery.

Done at Berlin, 20 December 1945.

Joseph T. McNarney

General

B. L. Montgomery

Field Marshal

L. Koeltz

General de Corps d’Armée

for P. Koenig

General d’Armée

G. Zhukov

Marshal of the Soviet Union

Amendment of Executive Order No. 9547 of May 2, 1945, Entitled “Providing for Representation of the United States in Preparing and Prosecuting Charges of Atrocities and War Crimes Against the Leaders of the European Axis Powers and Their Principal Agents and Accessories”

By virtue of the authority vested in me as President and Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, under the Constitution and statutes of the United States, it is ordered as follows:

1. In addition to the authority vested in the Representative of the United States and its Chief of Counsel by Paragraph 1 of Executive Order No. 9547 of May 2, 1945, to prepare and prosecute charges of atrocities and war crimes against such of the leaders of the European Axis powers and their accessories as the United States may agree with any of the United Nations to bring to trial before an international military tribunal, such Representative and Chief of Counsel shall have the authority to proceed before United States military or occupation tribunals, in proper cases, against other Axis adherents, including but not limited to cases against members of groups and organizations declared criminal by the said international military tribunal.

2. The present Representative and Chief of Counsel is authorized to designate a Deputy Chief of Counsel, to whom he may assign responsibility for organizing and planning the prosecution of charges of atrocities and war crimes, other than those now being prosecuted as Case No. 1 in the international military tribunal, and, as he may be directed by the Chief of Counsel, for conducting the prosecution of such charges of atrocities and war crimes.

3. Upon vacation of office by the present Representative and Chief of Counsel, the functions, duties, and powers of the Representative of the United States and its Chief of Counsel, as specified in the said Executive Order No. 9547 of May 2, 1945, as amended by this order, shall be vested in a Chief of Counsel for War Crimes to be appointed by the United States Military Governor for Germany or by his successor.

4. The said Executive Order No. 9547 of May 2, 1945, is amended accordingly.

Harry S. Truman

The White House,

January 16, 1946.

(F. R. Doc. 46-893; Filed, Jan. 17, 1946; 11:08 a. m.)

US FORCES, EUROPEAN THEATER

| General Orders | } | 24 October 1946 |

| No. 301 | } | |

| Office of Chief of Counsel for War Crimes | I | |

| Chief Prosecutor | II | |

| Announcement of Assignments | III | |

I——OFFICE OF CHIEF OF COUNSEL FOR WAR CRIMES. Effective this date, the Office of Chief of Counsel for War Crimes is transferred to the Office of Military Government for Germany (US). The Chief of Counsel for War Crimes will report directly to the Deputy Military Governor and will work in close liaison with the Legal Adviser of the Office of Military Government for Germany and with the Theater Judge Advocate.

II——CHIEF PROSECUTOR. Effective this date, the Chief of Counsel for War Crimes will also serve as Chief Prosecutor under the Charter of the International Military Tribunal, established by the Agreement of 8 August 1945.

III——ANNOUNCEMENT OF ASSIGNMENTS. Effective this date, Brigadier General Telford Taylor, USA, is announced as Chief of Counsel for War Crimes, in which capacity he will also serve as Chief Prosecutor for the United States under the Charter of the International Military Tribunal, established by the Agreement of 8 August 1945.

By command of GENERAL McNARNEY:

C. R. HUEBNER

Major General, GSC,

Chief of Staff

Official:

GEORGE F. HERBERT

Colonel, AGD

Adjutant General

Distribution: D

ORGANIZATION AND POWERS OF CERTAIN MILITARY TRIBUNALS

The purpose of this Ordinance is to provide for the establishment of military tribunals which shall have power to try and punish persons charged with offenses recognized as crimes in Article II of Control Council Law No. 10, including conspiracies to commit any such crimes. Nothing herein shall prejudice the jurisdiction or the powers of other courts established or which may be established for the trial of any such offenses.

(a) Pursuant to the powers of the Military Governor for the United States Zone of Occupation within Germany and further pursuant to the powers conferred upon the Zone Commander by Control Council Law No. 10 and Articles 10 and 11 of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal annexed to the London Agreement of 8 August 1945 certain tribunals to be known as “Military Tribunals” shall be established hereunder.

(b) Each such tribunal shall consist of three or more members to be designated by the Military Governor. One alternate member may be designated to any tribunal if deemed advisable by the Military Governor. Except as provided in subsection (c) of this Article, all members and alternates shall be lawyers who have been admitted to practice, for at least five years, in the highest courts of one of the United States or its territories or of the District of Columbia, or who have been admitted to practice in the United States Supreme Court.

(c) The Military Governor may in his discretion enter into an agreement with one or more other zone commanders of the member nations of the Allied Control Authority providing for the joint trial of any case or cases. In such cases the tribunals shall consist of three or more members as may be provided in the agreement. In such cases the tribunals may include properly qualified lawyers designated by the other member nations.

(d) The Military Governor shall designate one of the members of the tribunal to serve as the presiding judge.

(e) Neither the tribunals nor the members of the tribunals or the alternates may be challenged by the prosecution or by the defendants or their counsel.

(f) In case of illness of any member of a tribunal or his incapacity for some other reason, the alternate, if one has been designated, shall take his place as a member in the pending trial. Members may be replaced for reasons of health or for other good reasons, except that no replacement of a member may take place, during a trial, other than by the alternate. If no alternate has been designated, the trial shall be continued to conclusion by the remaining members.

(g) The presence of three members of the tribunal or of two members when authorized pursuant to subsection (f) supra shall be necessary to constitute a quorum. In the case of tribunals designated under (c) above the agreement shall determine the requirements for a quorum.

(h) Decisions and judgments, including convictions and sentences, shall be by majority vote of the members. If the votes of the members are equally divided, the presiding member shall declare a mistrial.

(a) Charges against persons to be tried in the tribunals established hereunder shall originate in the Office of the Chief of Counsel for War Crimes, appointed by the Military Governor pursuant to paragraph 3 of the Executive Order Numbered 9679 of the President of the United States dated 16 January 1946. The Chief of Counsel for War Crimes shall determine the persons to be tried by the tribunals and he or his designated representative shall file the indictments with the Secretary General of the tribunals (see Article XIV, infra) and shall conduct the prosecution.

(b) The Chief of Counsel for War Crimes, when in his judgment it is advisable, may invite one or more United Nations to designate representatives to participate in the prosecution of any case.

In order to ensure fair trial for the defendants, the following procedure shall be followed:

(a) A defendant shall be furnished, at a reasonable time before his trial, a copy of the indictment and of all documents lodged with the indictment, translated into a language which he understands. The indictment shall state the charges plainly, concisely and with sufficient particulars to inform defendant of the offenses charged.

(b) The trial shall be conducted in, or translated into, a language which the defendant understands.

(c) A defendant shall have the right to be represented by counsel of his own selection, provided such counsel shall be a person qualified under existing regulations to conduct cases before the courts of defendant’s country, or any other person who may be specially authorized by the tribunal. The tribunal shall appoint qualified counsel to represent a defendant who is not represented by counsel of his own selection.

(d) Every defendant shall be entitled to be present at his trial except that a defendant may be proceeded against during temporary absences if in the opinion of the tribunal defendant’s interests will not thereby be impaired, and except further as provided in Article VI (c). The tribunal may also proceed in the absence of any defendant who has applied for and has been granted permission to be absent.

(e) A defendant shall have the right through his counsel to present evidence at the trial in support of his defense, and to cross examine any witness called by the prosecution.

(f) A defendant may apply in writing to the tribunal for the production of witnesses or of documents. The application shall state where the witness or document is thought to be located and shall also state the facts to be proved by the witness or the document and the relevancy of such facts to the defense. If the tribunal grants the application, the defendant shall be given such aid in obtaining production of evidence as the tribunal may order.

The tribunals shall have the power

(a) to summon witnesses to the trial, to require their attendance and testimony and to put questions to them;

(b) to interrogate any defendant who takes the stand to testify in his own behalf, or who is called to testify regarding another defendant;

(c) to require the production of documents and other evidentiary material;

(d) to administer oaths;

(e) to appoint officers for the carrying out of any task designated by the tribunals including the taking of evidence on commission;

(f) to adopt rules of procedure not inconsistent with this Ordinance. Such rules shall be adopted, and from time to time as necessary, revised by the members of the tribunal or by the committee of presiding judges as provided in Article XIII.

The tribunals shall

(a) confine the trial strictly to an expeditious hearing of the issues raised by the charges;

(b) take strict measures to prevent any action which will cause unreasonable delay, and rule out irrelevant issues and statements of any kind whatsoever;

(c) deal summarily with any contumacy, imposing appropriate punishment, including the exclusion of any defendant or his counsel from some or all further proceedings, but without prejudice to the determination of the charges.

The tribunals shall not be bound by technical rules of evidence. They shall adopt and apply to the greatest possible extent expeditious and non-technical procedure, and shall admit any evidence which they deem to have probative value. Without limiting the foregoing general rules, the following shall be deemed admissible if they appear to the tribunal to contain information of probative value relating to the charges: affidavits, depositions, interrogations, and other statements, diaries, letters, the records, findings, statements and judgments of the military tribunals and the reviewing and confirming authorities of any of the United Nations, and copies of any document or other secondary evidence of the contents of any document, if the original is not readily available or cannot be produced without delay. The tribunal shall afford the opposing party such opportunity to question the authenticity or probative value of such evidence as in the opinion of the tribunal the ends of justice require.

The tribunals may require that they be informed of the nature of any evidence before it is offered so that they may rule upon the relevance thereof.

The tribunals shall not require proof of facts of common knowledge but shall take judicial notice thereof. They shall also take judicial notice of official governmental documents and reports of any of the United Nations, including the acts and documents of the committees set up in the various Allied countries for the investigation of war crimes, and the records and findings of military or other tribunals of any of the United Nations.

The determinations of the International Military Tribunal in the judgments in Case No. 1 that invasions, aggressive acts, aggressive wars, crimes, atrocities or inhumane acts were planned or occurred, shall be binding on the tribunals established hereunder and shall not be questioned except insofar as the participation therein or knowledge thereof by any particular person may be concerned. Statements of the International Military Tribunal in the judgment in Case No. 1 constitute proof of the facts stated, in the absence of substantial new evidence to the contrary.

The proceedings at the trial shall take the following course:

(a) The tribunal shall inquire of each defendant whether he has received and had an opportunity to read the indictment against him and whether he pleads “guilty” or “not guilty.”

(b) The prosecution may make an opening statement.

(c) The prosecution shall produce its evidence subject to the cross examination of its witnesses.

(d) The defense may make an opening statement.

(e) The defense shall produce its evidence subject to the cross examination of its witnesses.

(f) Such rebutting evidence as may be held by the tribunal to be material may be produced by either the prosecution or the defense.

(g) The defense shall address the court.

(h) The prosecution shall address the court.

(i) Each defendant may make a statement to the tribunal.

(j) The tribunal shall deliver judgment and pronounce sentence.

A Central Secretariat to assist the tribunals to be appointed hereunder shall be established as soon as practicable. The main office of the Secretariat shall be located in Nuernberg. The Secretariat shall consist of a Secretary General and such assistant secretaries, military officers, clerks, interpreters and other personnel as may be necessary.

The Secretary General shall be appointed by the Military Governor and shall organize and direct the work of the Secretariat. He shall be subject to the supervision of the members of the tribunals, except that when at least three tribunals shall be functioning, the presiding judges of the several tribunals may form the supervisory committee.

The Secretariat shall:

(a) Be responsible for the administrative and supply needs of the Secretariat and of the several tribunals.

(b) Receive all documents addressed to tribunals.

(c) Prepare and recommend uniform rules of procedure, not inconsistent with the provisions of this Ordinance.

(d) Secure such information for the tribunals as may be needed for the approval or appointment of defense counsel.

(e) Serve as liaison between the prosecution and defense counsel.

(f) Arrange for aid to be given defendants and the prosecution in obtaining production of witnesses or evidence as authorized by the tribunals.

(g) Be responsible for the preparation of the records of the proceedings before the tribunals.

(h) Provide the necessary clerical, reporting and interpretative services to the tribunals and its members, and perform such other duties as may be required for the efficient conduct of the proceedings before the tribunals, or as may be requested by any of the tribunals.

The judgments of the tribunals as to the guilt or the innocence of any defendant shall give the reasons on which they are based and shall be final and not subject to review. The sentences imposed may be subject to review as provided in Article XVII, infra.

The tribunal shall have the right to impose upon the defendant, upon conviction, such punishment as shall be determined by the tribunal to be just, which may consist of one or more of the penalties provided in Article II, Section 3 of Control Council Law No. 10.

(a) Except as provided in (b) infra, the record of each case shall be forwarded to the Military Governor who shall have the power to mitigate, reduce or otherwise alter the sentence imposed by the tribunal, but may not increase the severity thereof.

(b) In cases tried before tribunals authorized by Article II (c), the sentence shall be reviewed jointly by the zone commanders of the nations involved, who mitigate, reduce or otherwise alter the sentence by majority vote, but may not increase the severity thereof. If only two nations are represented, the sentence may be altered only by the consent of both zone commanders.

No sentence of death shall be carried into execution unless and until confirmed in writing by the Military Governor. In accordance with Article III, Section 5 of Law No. 10, execution of the death sentence may be deferred by not to exceed one month after such confirmation if there is reason to believe that the testimony of the convicted person may be of value in the investigation and trial of other crimes.

Upon the pronouncement of a death sentence by a tribunal established thereunder and pending confirmation thereof, the condemned will be remanded to the prison or place where he was confined and there be segregated from the other inmates, or be transferred to a more appropriate place of confinement.

Upon the confirmation of a sentence of death the Military Governor will issue the necessary orders for carrying out the execution.

Where sentence of confinement for a term of years has been imposed the condemned shall be confined in the manner directed by the tribunal imposing sentence. The place of confinement may be changed from time to time by the Military Governor.

Any property declared to be forfeited or the restitution of which is ordered by a tribunal shall be delivered to the Military Governor, for disposal in accordance with Control Council Law No. 10, Article II (3).

Any of the duties and functions of the Military Governor provided for herein may be delegated to the Deputy Military Governor. Any of the duties and functions of the Zone Commander provided for herein may be exercised by and in the name of the Military Governor and may be delegated to the Deputy Military Governor.

This Ordinance becomes effective 18 October 1946.

By order of Military Government.

AMENDING MILITARY GOVERNMENT ORDINANCE NO. 7 OF 18 OCTOBER 1946, ENTITLED “ORGANIZATION AND POWERS OF CERTAIN MILITARY TRIBUNALS”

Article V of Ordinance No. 7 is amended by adding thereto a new subdivision to be designated “(g)”, reading as follows:

“(g) The presiding judges, and, when established, the supervisory committee of presiding judges provided in Article XIII shall assign the cases brought by the Chief of Counsel for War Crimes to the various Military Tribunals for trial.”

Ordinance No. 7 is amended by adding thereto a new article following Article V to be designated Article V-B, reading as follows:

“(a) A joint session of the Military Tribunals may be called by any of the presiding judges thereof or upon motion, addressed to each of the Tribunals, of the Chief of Counsel for War Crimes or of counsel for any defendant whose interests are affected, to hear argument upon and to review any interlocutory ruling by any of the Military Tribunals on a fundamental or important legal question either substantive or procedural, which ruling is in conflict with or is inconsistent with a prior ruling of another of the Military Tribunals.

“(b) A joint session of the Military Tribunals may be called in the same manner as provided in subsection (a) of this Article to hear argument upon and to review conflicting or inconsistent final rulings contained in the decisions or judgments of any of the Military Tribunals on a fundamental or important legal question, either substantive or procedural. Any motion with respect to such final ruling shall be filed within ten (10) days following the issuance of decision or judgment.

“(c) Decisions by joint sessions of the Military Tribunals, unless thereafter altered in another joint session, shall be binding upon all the Military Tribunals. In the case of the review of final rulings by joint sessions, the judgments reviewed may be confirmed or remanded for action consistent with the joint decision.

“(d) The presence of a majority of the members of each Military Tribunal then constituted is required to constitute a quorum.

“(e) The members of the Military Tribunals shall, before any joint session begins, agree among themselves upon the selection from their number of a member to preside over the joint session.

“(f) Decisions shall be by majority vote of the members. If the votes of the members are equally divided, the vote of the member presiding over the session shall be decisive.”

Subdivisions (g) and (h) of Article XI of Ordinance No. 7 are deleted; subdivision (i) is re-lettered “(h)”; subdivision (j) is relettered “(i)”; and a new subdivision, to be designated “(g)”, is added, reading as follows:

“(g) The prosecution and defense shall address the court in such order as the Tribunal may determine.”

This Ordinance becomes effective 17 February 1947.

By order of the Military Government.

Secretaries General

| Mr. Charles E. Sands | From 25 October 1946 to 17 November 1946. |

| Mr. George M. Read | From 18 November 1946 to 19 January 1947. |

| Mr. Charles E. Sands | From 20 January 1947 to 18 April 1947. |

| Colonel John E. Ray | From 19 April 1947 to 9 May 1948. |

| Dr. Howard H. Russell | From 10 May 1948 to 1 December 1949. |

Deputy and Executive Secretaries General

| Mr. Charles E. Sands | Deputy from 18 November 1946 to 10 January 1947. |

| Judge Richard D. Dixon | Acting Deputy from 25 November 1946 to 5 March 1947. |

| Mr. Henry A. Hendry | Deputy from 6 March 1947 to 9 May 1947. |

| Mr. Homer B. Millard | Executive Secretary General from 3 March 1947 to 5 October 1947. |

| Lieutenant Colonel Herbert N. Holsten | Executive Secretary General from 6 October 1947 to 30 April 1949. |

Assistant Secretaries General

[Since many trials were being held simultaneously, an Assistant Secretary General was designated by the Secretary General for each case. Assistant Secretaries General are listed with the members of each tribunal.]

Marshals of Military Tribunals

| Colonel Charles W. Mays | From 4 November 1946 to 5 September 1947. |

| Colonel Samuel L. Metcalfe | From 7 September 1947 to 29 August 1948. |

| Captain Kenyon S. Jenckes | From 30 August 1948 to 30 April 1949. |

Court Archives

| Mrs. Barbara S. Mandellaur | Chief from 21 February 1947 to 30 April 1949. |

Defense Information Center

| Mr. Lambertus Wartena | Defense Administrator from 3 March 1947 to 16 September 1947. |

| Lieutenant Colonel Herbert N. Holsten | Defense Administrator from 17 September 1947 to 19 October 1947. |

| Major Robert G. Schaefer | Defense Administrator from 20 October 1947 to 30 April 1949. |

“The Medical Case”

MILITARY TRIBUNAL NO. 1

CASE 1

The United States of America

—against—

Karl Brandt, Siegfried Handloser, Paul Rostock, Oskar Schroeder, Karl Genzken, Karl Gebhardt, Kurt Blome, Rudolf Brandt, Joachim Mrugowsky, Helmut Poppendick, Wolfram Sievers, Gerhard Rose, Siegfried Ruff, Hans Wolfgang Romberg, Viktor Brack, Hermann Becker-Freyseng, Georg August Weltz, Konrad Schaefer, Waldemar Hoven, Wilhelm Beiglboeck, Adolf Pokorny, Herta Oberheuser, and Fritz Fischer, Defendants

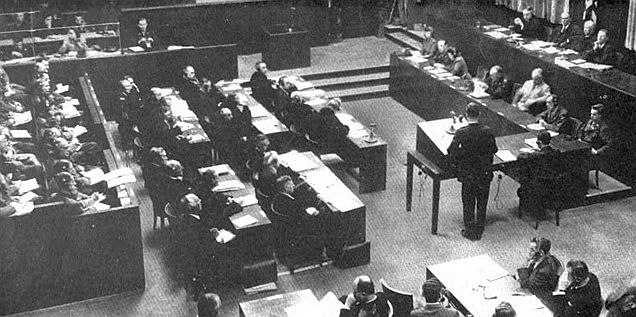

The “Doctors Trial” or “Medical Case”—officially designated United States of America vs. Karl Brandt, et al. (Case No. 1)—was tried at the Palace of Justice in Nuernberg before Military Tribunal I. The Tribunal convened 139 times, and the duration of the trial is shown by the following schedule:

| Indictment filed | 25 | October 1946 |

| Indictment served | 5 | November 1946 |

| Arraignment | 21 | November 1946 |

| Prosecution opening statement | 9 | December 1946 |

| Defense opening statement | 29 | January 1947 |

| Prosecution closing statement | 14 | July 1947 |

| Defense closing statements | 14-18 | July 1947 |

| Judgment | 19 | August 1947 |

| Sentences | 20 | August 1947 |

| Affirmation of sentences by Military Commander of the United States Zone of Occupation | 25 | November 1947 |

| Order of the United States Supreme Court denying writ of habeas corpus | 16 | February 1948 |

The death sentences imposed on Karl Brandt, Rudolf Brandt, Karl Gebhardt, Joachim Mrugowsky, Viktor Brack, Wolfram Sievers, and Waldemar Hoven were put into execution on 2 June 1948.

The English transcript of the Court proceedings runs to 11,538 mimeographed pages. The prosecution introduced into evidence 570 written exhibits (some of which contained several documents), and the defense 901 written exhibits. The Tribunal heard oral testimony of 32 witnesses called by the prosecution and of 30 witnesses, excluding the defendants, called by the defense. Each of the 23 defendants testified in his own behalf, and each was subject to examination on behalf of other defendants. The exhibits offered by both the prosecution and defense contained documents, photographs, affidavits, interrogatories, letters, maps, charts, and other written evidence. The prosecution introduced 49 affidavits; the defense introduced 535 affidavits. The prosecution called 3 defense affiants for cross-examination; the defense called 13 prosecution affiants for cross-examination. The case-in-chief of the prosecution took 25 court days and the case for the 23 defendants took 107 court days. The Tribunal was in recess between 18 and 27 January 1947 to give the defense additional time to prepare its case. A further recess was taken from 3 to 14 July 1947 to allow both prosecution and defense time for the preparation of their closing arguments.

The members of the Tribunal and prosecution and defense counsel are listed on the ensuing pages. Prosecution counsel were assisted in preparing the case by Walter Rapp (Chief of the Evidence Division), Fred Rodell, Norbert Barr, and Herbert Meyer, interrogators, and Henry Sachs, Eleanor Anspacher, Nancy Fenstermacher, and Olga Lang, research and documentary analysts.

Selection and arrangement of the “Medical Case” material published herein was accomplished principally by Arnost Horlik-Hochwald, working under the general supervision of Drexel A. Sprecher, Deputy Chief Counsel and Director of Publications, Office U. S. Chief of Counsel for War Crimes. Catherine W. Bedford, Henry Buxbaum, Emilie Evand, Gertrude Ferencz, Paul H. Gantt, Constance Gavares, Olga Lang, Helga Lund, Gwendoline Niebergall, Johanna K. Reischer, Hans Sachs, and Enid M. Standring assisted in selecting, compiling, editing, and indexing the numerous papers.

John H. E. Fried, Special Legal Consultant to the Tribunals, reviewed and approved the selection and arrangement of the material as the designated representative of the Nuernberg Tribunals.

Final compilation and editing of the manuscript for printing was administered by the War Crimes Division, Office of the Judge Advocate General, under the direct supervision of Richard A. Olbeter, Chief, Special Projects Branch, with Alma Soller as editor and John W. Mosenthal as research analyst.

OFFICE OF MILITARY GOVERNMENT FOR GERMANY (U. S.)

APO 742

| General Orders | } | |

| No. 68 | } | 26 October 1946 |

Pursuant to Military Government Ordinance No. 7

1. Pursuant to Military Government Ordinance No. 7, 24 October 1946, entitled “Organization and Powers of Certain Military Tribunals”, there is hereby constituted, Military Tribunal I.

2. The following are designated as members of Military Tribunal I:

| Walter B. Beals | Presiding Judge |

| Harold L. Sebring | Judge |

| Johnson Tal Crawford | Judge |

| Victor C. Swearingen | Alternate Judge |

3. The Tribunal shall convene at Nuernberg, Germany, to hear such cases as may be filed by the Chief of Counsel for War Crimes or by his duly designated representative.

4. This order is effective as of 25 October 1946.

By command of LIEUTENANT GENERAL CLAY:

C. K. Gailey

Brigadier General, USA

Chief of Staff

Official:

G. H. Garde

Lieutenant Colonel, AGD

Adjutant General

Distribution: “B” plus

2-NRU USFET

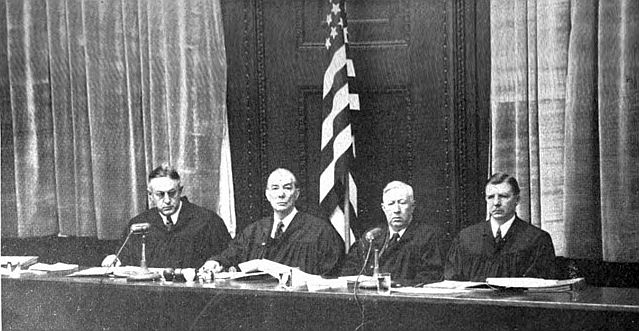

Judge Walter B. Beals, Presiding Judge.

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of Washington.

Judge Harold L. Sebring, Member.

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Florida.

Judge Johnson T. Crawford, Member.

Formerly Judge of a District Court of the State of Oklahoma.

Judge Victor C. Swearingen, Alternate Member.

Formerly Special Assistant to the Attorney General of the United States.

ASSISTANT SECRETARIES GENERAL

| Mr. Dehull N. Travis | From 21 November 1946 to 6 June 1947 |

| Major Mills C. Hatfield | From 17 June 1947 to 14 July 1947 |

| Miss M. A. Royce | From 15 July 1947 to 20 August 1947 |

TRIBUNAL I—CASE ONE.

Left to Right: Harold L. Sebring; Walter B. Beals, Presiding;

Johnson Tal Crawford; Victor C. Swearingen, Alternate.

General view of courtroom on opening day of trial. Upper left: Court reporter and translators. Left: Defendants and defense counsel. At rostrum: Brigadier General Telford Taylor, Chief of Counsel for War Crimes Right: Judges and court clerks of Tribunal I. Foreground: Members of the prosecution staff with Mr. James McHaney, Chief Prosecutor, and Mr. Alexander Hardy, Associate Prosecutor, seated at table directly behind Brigadier General Taylor.