* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Scarlet Woman

Date of first publication: 1901

Author: Joseph Hocking

Date first posted: May 29, 2017

Date last updated: May 29, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170559

This ebook was produced by: Al Haines, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

GREATER LOVE.

LEST WE FORGET.

THE PURPLE ROBE.

FIELDS OF FAIR RENOWN.

ISHMAEL PENGELLY.

THE STORY OF ANDREW FAIRFAX.

JABEZ EASTERBROOK.

THE MONK OF MAR SABA.

ZILLAH.

MISTRESS NANCY MOLESWORTH.

THE BIRTHRIGHT.

AND SHALL TRELAWNY DIE?

ESAU.

ALL MEN ARE LIARS.

THE COMING OF THE KING.

ROGER TREWINION.

WEAPONS OF MYSTERY.

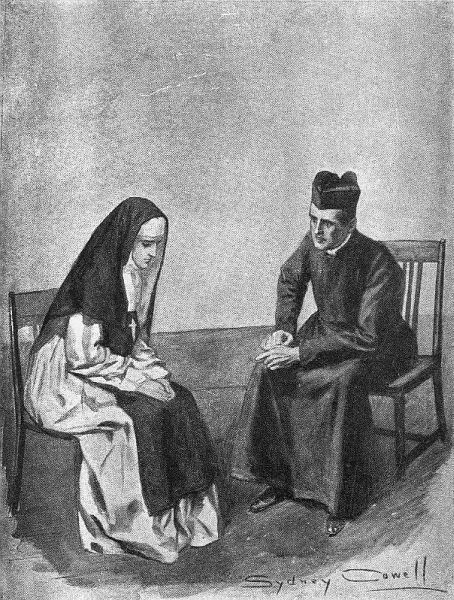

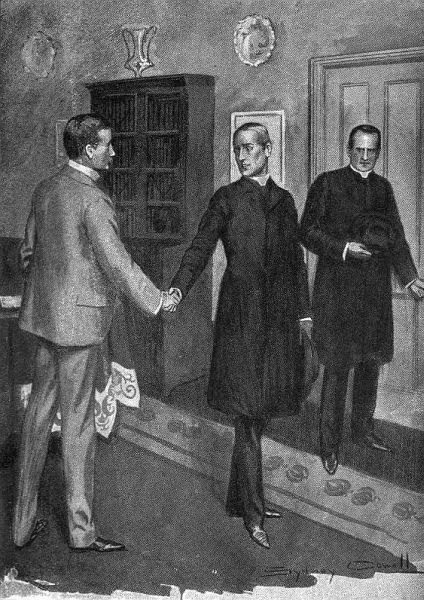

“ ‘Better break his heart than that we should both be untrue

to our faith?’ ” (Page 131.)

THE

SCARLET WOMAN

A Novel

BY

JOSEPH HOCKING

Author of “Mistress Nancy Molesworth,” “The Birthright,” “All Men are Liars,”

“The Story of Andrew Fairfax,” &c., &c.

ILLUSTRATED BY SYDNEY COWELL

WARD, LOCK & CO., LIMITED

LONDON AND MELBOURNE

THE SCARLET WOMAN

The three great working forces of life are ambition, necessity, and love. Lacking any one of these, man is wanting in motive power; lacking all of them, he generally becomes drift, swept hither and thither by the waves of life. Norman Lancaster possessed none of them. Certainly he was not ambitious, as the word is usually understood. He desired neither fame nor position. He had no need to put forth effort in order to obtain life’s necessities. Fortunately, or unfortunately for him, he possessed more money than he needed. As for love, his friends declared that he was a stranger to this the greatest passion of which the human heart is capable, and which makes or mars the life of the world. This may explain why, when he returned to London, after some months’ absence, he seemed so bored.

“I think I have tried everything now,” he said, as, with a sigh, he threw himself into an armchair and cut the end of a cigar. He smoked silently a few minutes, then went on thinking.

“The world’s a pretty weary business,” he continued presently, “and that old cynic was right when he said that life was ‘short and dirty.’ All places are alike, and people are uniformly dull. I did think that African trip would have interested me, but it proved as tame as everything else. I wish I could hit upon something that would really interest me—something new—something that would yield freshness and sweetness. But Solomon was right: ‘There is nothing new under the sun.’ ”

There was nothing in Lancaster’s appearance suggestive of pessimism. He was rather a good-looking fellow, who had barely reached the prime of life. True, there was a lack of earnestness in his eyes, but otherwise he appeared healthy and vigorous. His surroundings, moreover, were not those of a man unable to command the world’s good things. The room was replete with all the comforts, not only of a man of wealth, but of culture and taste. For a bachelor’s snuggery it was more than usually elegant. Pictures, statuary, books, all revealed the educated, refined man.

The truth was, Lancaster was suffering from surfeit. At twenty-one he had become possessed of an ample fortune, and almost ever since his main object had been to obtain happiness, which, as a consequence, had fled from him. Unlike many others in his position, his tastes led him away from the ordinary pursuits of a gay young man about town. Coarseness and vulgarity he detested; society, as it is usually understood, was to him poor and tame, and work for work’s sake he did not enjoy.

He had tried most things, but had extracted very little pleasure from them. He had painted pictures, written a book, gone into Parliament, travelled, and dabbled both in science and philosophy, but at the age of thirty-three he had come to the conclusion that life was a weary business, and he earnestly longed for a new sensation. Presently he heard a knock at the door, and a servant entered bringing a card.

“Tom Carelton,” he said aloud, as he read it. “All right; show him in. Tom is a good fellow,” he continued, when the girl had gone, “and he may have some news worth communicating.”

“Ah, Lancaster!” cried the young man who entered, “I’m glad to see you. I heard you had come home, and took my chance of finding you in.”

“I am glad you have come,” replied Lancaster. “I think I have a fit of the blues, and cheerful fellows like you are always welcome. Say, old chap, how do you manage to keep such a smiling face?”

“Haven’t time to get low-spirited,” replied the other. “There’s nothing like work to make the world bright. Providence seems to have a grudge against those who have nothing to do.”

“I think you are right,” replied Lancaster grimly.

“You see,” went on Carelton gaily, although a close observer might have seen an anxious look in his eyes, “I am obliged to keep my nose to the grindstone. I have a wife and youngsters.”

“How many youngsters have you?”

“Three.”

“And still keep happy?”

“Yes; that is——”

“What?”

“Oh, nothing! I pay my way, and find life a jolly business.”

“I wonder,” said Lancaster, “had I been obliged to grind hard for a bit of bread and cheese, and had a wife and children to keep, if I should find the world a bit more cheerful?”

“Still on those lines, Lancaster? Why, you ought to be ashamed of yourself.”

“I know I ought; in fact, I think I am. There is something wrong in my make-up, I expect.”

“And yet when we were students together you were as gay as a lark.”

“Yes, I was; we all were, in fact. But now I come to look at you more closely, you don’t appear quite so gay as usual.”

“No?”

“Are you bothered, old man?” And there was a look of kindness in Lancaster’s eyes.

“Yes; a bit.”

“But you said just now that nothing was wrong at home.”

“Oh, no! nothing of that nature.”

“Then I suppose you are troubling about the welfare of other people, as usual.”

Carelton did not reply for some seconds; then he burst out suddenly—

“Do you remember Jack Gray, Lancaster?”

“Yes; a little. I knew his eldest brother Horace well, but Jack belonged to a younger generation. Still, I used to know him; a bookish, sensitive fellow, rather given to brooding.”

“That is so; but as good a fellow as ever breathed.”

“He’s all right, I hope?”

“No; he’s all wrong.”

“Not gone to the dogs, surely? Why, I thought him of a religious turn of mind.”

“He’s not gone to the bad in the usual way; as you say, he’s of a different nature.”

“Who’s the woman?”

“How do you know there’s a woman?”

“Oh, there always is,” replied Lancaster. “Do I know her?”

“Only a little, but you have seen her—Gertrude Winthrop. You met her at Brighton once.”

“Oh, yes; I remember. A poetical creature. Awfully religious, too. I used to think she was in love with a Roman Catholic priest. She tried very hard one night to prove to me that all who remained outside the Roman fold would provide fuel for the bottomless pit.”

“Yes; there’s the crux of the whole mischief.”

“How?”

“Well, Jack Gray fell in love with her, and they were engaged.”

“The girl has turned out a jilt, I suppose?”

“No—at least, not in the orthodox way. They quarrelled about something, and Jack believed that she had thrown him over for some other fellow. Well, he was awfully cut up. You know what an intense nature he has. He can never do anything by halves. As you may be aware, he is a Roman Catholic, and in his despair he determined to enter the Roman priesthood.”

“A good idea,” laughed Lancaster. “Do you know, I’ve often thought of trying to find out the secret of Romanism. After all, there is something fascinating in the thought of submitting yourself to an infallible authority. Once that is done, there is no more doubt, no more fear or worry. Confess, do penance, say prayers, receive absolution, and then take your ease.”

“The thing is to find the infallible authority,” replied Carelton.

“Yes; of course, I should kick over the traces in a week, but at the first blush it’s fascinating. I almost envy Jack Gray. He must be experiencing a new sensation.”

“He entered a monastery because he believed Gertrude Winthrop had jilted him. Well, she has done nothing of the sort. She’s as fond of him as he is of her. Indeed, she has taken a similar course, and will shortly take vows.”

“Well, let them.”

“They will both destroy their lives if they do. Jack is a brilliant fellow; he would make his mark anywhere. He has money, too, and is well connected. If he is allowed to take vows, he will lose his money, and his career will be ruined.”

“Well, what can be done?”

“It has just come to my knowledge that Gertrude is in reality breaking her heart for Jack, while I am sure that if Jack knew of it, he would immediately give up all idea of the priesthood, and come back to life.”

“You are sure the girl is really in love with him?” asked Lancaster drily.

“I am sure she is.”

“Then why does she not let him know?”

“For several reasons. First, she is in a Roman Catholic institution as a novice—whatever that may mean—and she believes that Jack has ceased to care for her. Moreover, she is closely guarded by her superiors, and, consequently, even if she desired to convey any news to her lover, it would be extremely difficult.”

“But why does not some one write to Jack and tell him the truth?” asked Lancaster quickly.

“The same objections are in force in his case,” was Carelton’s reply. “His father is dead, and his mother has been persuaded by the priests that it is Jack’s duty to take orders. As a consequence, she takes care not to tell him anything that might have a tendency to alter his purpose.”

“But you could write?”

“Useless, my boy; all the letters would be intercepted, read, and destroyed. The institution into which he has gone has very strict rules. I do not know much about these places myself, but I have discovered that no communication can reach him without his superior’s consent.”

“But Horace could visit his brother, surely?”

“Horace is a strict Catholic, and also believes it Jack’s duty to become a successor of the Apostles. Oh, I’ve pleaded with Horace, but I can make no headway with him—not a bit. As you know, the Romanists are desirous of converting England, and they believe that Jack would greatly help them. Most of the Catholic priests come from the people, and hosts of them have but little education. Jack is well connected; he has a number of influential friends among the Protestants; he is a scholarly fellow, too; and they believe he would have considerable influence in circles which at present the ordinary priest cannot enter. Indeed, I am told that Jack is intended as a missionary to the cultured classes in England. He has a good old name, has hosts of friends, besides being handsome and agreeable. There is no doubt about it, he would have tremendous influence, especially among women. As a consequence, every effort is being made to retain him.”

“Well, my boy, I can suggest a solution of the business.”

“What?” asked Carelton eagerly.

“Go to this monastery, wherever it is, get admission, and tell him.”

“Impossible again. The truth is, I have appealed to a priest who, I believe, is Horace Gray’s confessor. I have told him that Jack’s life will be wrecked by becoming a priest. I showed him how he would be far happier married, and would also attain to a high position, either in politics or literature, if he got rid of these foolish ideas and came back to the world again.”

“I see. Well, what success did you have?”

“Oh, I bungled the business. The fellow told me that no vocation was so high as that of the priest’s; that all careers paled into insignificance when compared with that of a missioner of the one true faith of the world. He would not hear of the claims of love; it was the snare of the devil, he said. Jack was called of God to enter the priesthood, and any one who tried to hinder him, or did anything to shake his decision, would be an enemy to truth.”

“And yet you say the fellow is breaking his heart for this girl?”

“Horace admitted it.”

“While she—Gertrude Winthrop—still loves him?”

“I am sure of it. I tell you it maddens me when I think of it. Jack is such a good fellow. Up to the time of his becoming engaged to Gertrude, although always religiously inclined, he paid but little attention to any of the churches. During the first months of his engagement he was as gay as a lark. He had marked out his career, too; indeed, he was the accepted candidate for a constituency in Devonshire, and there was every probability of his entering Parliament at the next election. He is a brilliant speaker, has an intimate knowledge of current questions, and I am perfectly certain that in a few years he would have been a Cabinet minister. Gertrude, too, would have been a help to him, and he might have been happy and useful, while as a Romish priest—God help him!”

“Oh, I don’t see that. Think of Newman, Manning, and others. Career!—from one standpoint the Catholic priesthood is unrivalled.”

“I don’t pretend to be a theologian, but a Catholic priest, if he be true to his vows, is a dead man. I know Jack, and love him—love him as a brother—and I tell you, while they may twist his conscience into believing that he will be doing the will of God by taking the course suggested, he will be wrecking his life, blotting out all happiness, and blighting not only his own existence, but that of Gertrude as well.”

“Well, personally,” yawned Lancaster, “I don’t care much about these things. All the same, the affair savours of romance. I wish something would happen to me like this. As far as I can see, nothing is worth being interested in.”

“Unless Jack is acquainted of Gertrude’s feelings towards him in a fortnight, it will be too late.”

“Too late! How?”

“He will have bound himself.”

“And taken life-long vows to celibacy and all the rest of the paraphernalia?”

“Yes.”

“It would be a pity, wouldn’t it?” said Lancaster, like one musing. “And yet I don’t know. After all, ’twill be a new sensation for him, and the life of the world offers precious little.”

“You say that because you are cold-blooded,” cried Carelton; “because you’ve never known what it is to love and be loved by a true woman. You don’t know what it is to have children climb on your knee. If you did you would talk differently.”

“Perhaps I should,” replied Lancaster, speaking slowly. “No, I don’t think I was ever in love. It’s a curious confession, I know, but I don’t think I ever was. I did have some flirtations once, but—no, I was never really in love. I wish I could feel what such fellows as you tell me a man ought to feel. I should find some pleasure in life, then. I daresay, too, that, like you, I should be maddened at the position of Jack Gray.”

“No man knows what it is to live until he has been really in love,” replied Carelton. “I tell you, Lancaster, that the greatest, purest joy in life, humanly speaking, is to feel a pure woman’s lips against yours—the lips of the one woman in the world to you, and to hear her confess her love for you.”

“Women tell that story to so many men,” remarked Lancaster drily.

“Not all women,” replied Carelton. “I know that love is abused, but it’s the joy of life still. Take it away and life is one-sided, poor, almost worthless, to millions. That is why I am so grieved about poor Jack.”

“Where is this monastery in which you say he is immured?” asked Lancaster presently.

“In Ireland.”

“In Ireland, eh? What part?”

Carelton told him.

For some time both men were silent. Carelton smoked steadily, but he noticed that Lancaster’s cigar had gone out.

“Would it really make you happy if Gray came back to life again?” asked Lancaster presently.

“It would indeed,” replied the other, “but I almost give up hope. It is not an affair that one can talk about, and I know of no one who would undertake the mission.”

“I’ll go, if you like,” said Lancaster.

“You?”

“Yes. Won’t I do?”

“Do? of course. But do you really mean it?”

“Yes.”

“But, mind you, it is a difficult business. I know that, because I’ve tried to find out the exact facts of the case.”

“So much the better. I’ll go, anyhow.”

“I say, Norman, old chap, you are a good fellow!”

“Not a bit of it. I’m going because it interests me; it promises a new sensation. I’ve nothing to keep me here in London; I’ve no ties. My housekeeper is a distant relative and a most trustworthy old lady. Besides, the idea of outwitting those priests, and seeing the look on Jack Gray’s face when I tell him that the girl loves him, will be worth going to Ireland for. I’ve never been to the Emerald Island, either—I never thought it worth while; but—yes, the affair is full of promise. I’ll go.”

“And—and you’ll do your best?”

Carelton seemed so surprised at Lancaster’s promise that he scarcely knew what he was saying.

“Of course I’ll do my best. I’ll carry the thing through, too, see if I don’t!” He started up and walked to and fro in the room with an eager look in his eyes. “By Jove! Carelton, I’m glad you came; you’ve given me something to do.”

“When can you start?”

“To-morrow morning. But I must not go blindfolded; I must ask you a few questions first.”

“What do you wish to know?” asked Carelton.

The two men lit fresh cigars, and Lancaster looked steadily into the fire for some time without speaking. Presently he put on more coals, for the time was early March and the weather was cold.

“Jack Gray is still a novice, you say?” he remarked at length.

“He has been a novice for two years,” was Carelton’s reply. “As I said, his novitiate expires in a fortnight.”

“Then he must be entering some order.”

“He is. Unless you are successful, he will have taken a Jesuit’s vows in a fortnight.”

“A Jesuit, eh? I suppose the Jesuits supply the brains of the Papacy. Of course, during these two years he will have become imbued with the sophisms of the order.”

“I expect so,” Carelton replied with a sigh.

“In that case he will require no little persuasion to give up the business, even if I am able to get hold of him?”

Carelton nodded.

“I see difficulties,” Lancaster went on. “Assume I am successful in getting an interview with him. Admit, too, that he’s breaking his heart for a girl who is doing ditto for him. I tell him this; I put my case in the strongest possible way. What happens? I have no doubt he’ll be overjoyed for a second; but his joy will be followed by the influences of his order. He will think of all he has been taught these last two years, and he will be enmeshed like a fly in a spider’s web.”

“Possibly, but what are you driving after?”

“This. Two forces will be at work within him. First, there will be the love for the girl, partly destroyed by two years of living death, but fanned into something like life by what I shall tell him. Striving against this will be influences under which he has been living for two years. His mind will have been subjected to the authority of his superiors, his conscience will have become so twisted that he will regard disobedience to them as sin. I say these forces will struggle one against the other.”

“And the first will be the stronger,” cried Carelton eagerly. “Love is the strongest power on earth.”

Lancaster shook his head. “I am not at all sure,” he said. “But here is my difficulty—supposing he doubts Gertrude Winthrop’s love? True, I have your statement that the girl is dying for him; but what proofs have I, if Gray does not believe?”

“Her mother told me.”

“How does she know?”

“Her daughter told her.”

“How? by letter?”

“No. She went to see her.”

“Where?”

“In Ireland.”

“Whew! Both in Ireland, eh?”

“Yes, I think the fact of Jack going there led the girl to go. Well, a few weeks ago, Mrs. Winthrop went to see her daughter. Of course Gertrude is also a novice, but I imagine she is not so closely immured as she will be if she takes vows. In the course of conversation the truth came out. She still loves Jack.”

“But there is nothing to prove this.”

“Prove! What do you mean?”

“This: suppose Jack says to me, ‘I don’t believe Gertrude loves me. Give me some tangible evidence that what you say is true,’ what will my reply be?”

Carelton shook his head, then added quickly, “I believe the fellow will be so overjoyed at the news that he’ll ask for no proofs.”

“Evidently you know nothing of the influences of a Jesuit institution,” replied Lancaster.

“No, I know but little,” was the reply; “do you?”

“Yes, a little; not in detail, but I have read the life of Ignatius Loyola, and I know something of his teachings.”

“But, surely, that is—I hope this will not keep you from going?” cried Carelton.

“Oh, no, I’ll go; but I wish to know how I stand. By the way, where is this convent?”

Carelton told him.

“That’s not far from the place where Jack is,” was Lancaster’s rejoinder.

“No, it’s close by, but they might as well be a thousand miles apart. They will know nothing of the existence of each other. They are ignorant of the fact that each is dying for love of the other.”

“Still, it’s important. Well, now let me be sure that I understand this affair,” and Lancaster laughed like a boy. “Let me set forth the whole business as it appears to me,” and then he repeated point by point all that Carelton had told him.

“You might be a lawyer,” laughed his friend when he had finished.

“I did study law for a while,” replied Lancaster. “I thought I’d be a barrister. Still, I understand the case, don’t I?”

“Perfectly.”

“Then you must be off.”

Carelton looked up questioningly.

“I mean it, my dear boy. Stay, though, I’ll walk to King’s Cross with you, and then I must come back and do a few hours’ work.”

“Work, Lancaster?”

“Yes, I must read up all I can about the Jesuits and their order. I must try and find something of the rules of convents, especially this order to which you say Gertrude Winthrop is attached.”

“I see, yes. What time will you start in the morning?”

Lancaster studied Bradshaw for a few minutes before he replied.

“There is a train from Euston in the morning, which will land me at Holyhead just after four to-morrow afternoon. It catches a boat by which I ought to get to Dublin by about half-past eight.”

“Good,” replied Carelton. “You evidently believe in despatch. You have nothing to hinder you.”

“One of the advantages of being a bachelor,” laughed Lancaster. “If I were a married man like you, I should be detained several days before starting. Oh, those Romanists are wise people; there’s a great deal to be said for the celibacy of the clergy.”

“Be careful you don’t get converted,” was Carelton’s rejoinder.

“Oh, nothing’s impossible,” was the reply; “and I don’t know but I might do worse. Anyhow, I thank you, Carelton. I suppose I’ve no right to be on this business, but I’ve not been so excited for many a day. I am actually eager to start; my pulses are stirred, man, and I would not have missed this opportunity for a great deal. There, I am ready to go with you, and the walk will do me good.”

The two men went away together, and in a few minutes left the square in which Lancaster lived, and found their way into Gower Street.

“How do your trains run, Carelton?” asked Lancaster presently.

“I’ve plenty of time to catch the next from the suburban platform,” was the reply.

When they reached Euston Road they again talked of the mission Lancaster had undertaken.

“You say you are sure the superior of the monastery where Gray is has been warned against you?” asked Lancaster.

“Certain,” was the reply. “This confessor of Horace’s is a very clever fellow, and from hints which Mrs. Gray has let fall, I am sure I am a marked man.”

“In that case it is lucky we have never been seen together.”

“It is, indeed. All the same I am sure you would never be suspected of aiding me in such a seemingly Quixotic work.”

“No; why?”

“Oh, you know you are regarded as cold-blooded and cynical. Mrs. Gray would never believe you capable of interesting yourself.”

“I am surprised at myself,” replied Lancaster—“by Jove! there is a priest of some sort walking ahead of us.”

They turned in at King’s Cross Station and made their way towards the suburban platform.

“Turn back!” cried Carelton presently. “That’s Father Ritzoom on the platform.”

“Father Ritzoom! who’s he?”

“The priest we saw. The prime mover of the whole business, or I’m much mistaken. Don’t let him see us together. His mind is like a corkscrew; he can thread his way into any scheme or plot.”

“But I should like to see his face.”

“Don’t try, old fellow. There, he’s turned round. Don’t let him recognise you. He knows I am trying to get Jack Gray away from Ireland, and he will suspect any one he sees with me.”

“Very well, I’ll go; but I should like to have a closer look at him. These mysterious fellows always interest me. There, I’ll respect your fears. Good-night.”

“Good-night, old chap. God bless you for taking this matter up. I am sure you will be glad some day. Be sure you write to me regularly and let me know how matters are going on.”

On leaving the station Lancaster turned to have another look at the priest, but he had disappeared. Either he had gone into a waiting-room, or had entered one of the trains.

“The affair is promising, very promising,” cried the young man gaily. “I can see a fortnight’s good fun.”

Arrived at his house, he ransacked his shelves for certain books he wanted, and then read closely until the small hours of the morning.

Presently he rose with a yawn, “I must go to bed,” he said, “I am never worth a straw when I don’t get my sleep. Upon my word, I believe I am excited.” Nevertheless, fifteen minutes later Norman Lancaster was fast asleep.

The next morning the wind blew cold and winterly. Although March had come, occasional showers of sleet and snow swept across the city. “It’ll be a cheerless journey,” thought the young man as he got into a hansom, and told the cabby to drive to Euston. “What a fool I am! I don’t know what possessed me to promise Carelton to undertake such a hare-brained business. But there, a fellow is bound to make an ass of himself sometimes.”

He saw no one that he knew at the station, and having provided himself with a generous stock of literature, he took his seat in the corner of an empty carriage, and wrapped himself up warmly.

“I wish this affair had come off in summer instead of now,” thought Norman as he lit a cigar; “I should have extracted a little more fun from it.”

By the time the train reached Holyhead the whole landscape was covered with snow, and the wind blew half a gale. This did not trouble Norman, who knew that the boats were good, and that a fire would be burning in the saloon. When he left the train, however, he found that many of the passengers were exceedingly anxious. They questioned the sailors concerning the sea outside, whether the passage would be rough, how long they would be on the way, and whether they would be in danger of being wrecked. The sailors’ replies were by no means reassuring.

“There’s a ’igh sea, ma’am,” was the unvarying reply, for with true politeness they gave their answer to the ladies; “it’ll be a dirty crossin’, for we shall ’ave a ’ead wind. Most likely we sh’ll be more’n an ’our late at North Wall.”

Norman could not help laughing as he saw the disconsolate look on the questioners’ faces. Evidently they dreaded a rough sea.

“Do you think it’ll be better in the morning?” they asked.

“Very likely it will,” replied the sailors encouragingly.

“Would you advise me to go across to-night?” asked a middle-aged lady, whose teeth rattled “like a loose casement in the wind.”

“Well, mum, if you are not a good sailor you’ll ’ave a baddish time to-night,” was the comforting response, whereupon she told a porter to take her luggage to the nearest and best hotel.

Her example was quickly followed, for the little knot of people around the gangway speedily dispersed, and many made their way towards the refreshment room, evidently glad to find a leader brave enough to confess herself a coward.

Norman heard some one laugh close behind him.

“These people evidently believe in your excellent English proverb,” said a voice.

Norman turned, and saw a somewhat uncommon looking man. He was tall and largely built, while his height and breadth were seemingly increased by the long, heavy ulster he wore. His hair was raven black, and his chin, which was closely shaven, presented a blue appearance far more common among Italians than Englishmen. His lips, which were also shaven, were rather thick and somewhat sensual. His eyes were deep set and as black as his hair; the protruding forehead and black eyebrows adding to the somewhat repellent expression of his face. His voice, however, was soft and musical, and was not at all suggestive of the man’s stern strength.

“What is the proverb to which you refer?” asked Lancaster.

“Oh, a well worn one, as most of your proverbs are: ‘Discretion is the better part of valour.’ Doubtless, however, it is a very convenient maxim,” and he laughed again as he saw how few intended boarding the boat.

“And you intend going across?” asked Norman.

“Oh, yes. And you?”

For answer the young man presented his ticket to the official and walked down the gangway. “I am influenced by another saying, whether English or no, I am not sure,” he said, as the other again stood by his side.

“Let’s hear it.”

“ ‘Needs must, when the devil drives.’ ”

“I think you can claim that as English, too,” replied the other; “but it strikes me that you are not troubled much by maxims.”

Evidently the man desired to be friendly, and, as Lancaster felt glad of company, he took no notice of the freedom of the remark, except to ask why he had formed such an opinion of him.

“I judge you to be a good sailor,” was the reply. “You are perfectly indifferent to a rough sea, and are not easily thwarted in your purposes.”

“Who is this fellow?” thought Lancaster, as he went down to the saloon. “Anyhow he desires to be friendly, and as I shall probably never see him after to-night, I may as well talk with him as another.”

“Dinner, sir?” asked the waiter.

“What do you say?” asked the stranger.

“Certainly,” replied Norman. “I imagine we shall not reach Dublin much before midnight, and I feel hungry.”

They accordingly sat down at the same table, the stranger divesting himself of his ulster and hat, thereby revealing more clearly the proportions of the man. Norman noticed that his head was large, and of that shape which is often designated as square. He wore a suit of blue-black cloth, rather rough in texture, the coat being short and double-breasted, thus accentuating his great breadth of chest and squareness of shoulder.

“He might be a naval captain but for his lack of moustache,” thought Norman, “or he might be a political refugee, or a foreign spy. I don’t think he’s English, although he speaks our language perfectly. Upon my word, I feel curious about him.”

“Apparently you do not feel troubled about a head wind nor a rough sea,” he said aloud, as his companion attacked the dinner with evident relish.

“No, a rough sea does not trouble me. I don’t know what illness of any sort means.”

“You are young yet,” ventured Norman.

“Yes; how old should you think?”

Lancaster looked at him closely and knew not what to answer. He might be only thirty-five, he might be fifty-five. Not a grey hair appeared among his black locks, and his face was free from wrinkles. The fact that he was clean-shaven, too, made him look younger than if he had allowed his beard to grow; nevertheless, his eyes, black and brilliant as they were, did not suggest youth, while the whole expression of the face spoke of years and experience.

“I’ll not venture a guess,” replied Lancaster.

The man laughed as though he were pleased.

“You English are cautious,” he said; “indeed, discretion is a characteristic of your race. That fact was revealed just now when so many decided to wait until to-morrow morning rather than face a choppy sea. I think, as a nation, you owe much of your success to the fact; all the same, you are——”

He stopped suddenly and looked straight at Lancaster’s eyes.

“What?” asked the young man, feeling that the other awaited the question.

“Cautious in the wrong place.”

“Yes; why?”

“Oh, the reasons are too numerous to mention,” and he went on with his dinner.

For a moment Lancaster felt like defending his nation, but he had an idea that his companion was trying to make him communicative, so he turned the conversation into a slightly different channel.

“And your race, your nation, what are their characteristics?” he asked.

“I have no race, no nation.”

“No?”

“I am cosmopolitan. When I am in Spain I am a Spaniard, in Italy I am an Italian, in France a Frenchman.”

“And in England?”

“Oh, in England I am nothing.”

“Why?”

“The English are so narrow, so insular. They believe in nothing outside their little foggy island”; and again he fixed his searching eyes on Lancaster’s face.

The young man laughed, but gave no other reply.

The man was evidently somewhat disappointed at the other’s reticence. “Don’t you think so?” he said presently.

“I have never paid much attention to the subject,” replied Lancaster.

“Wherever your countrymen go,” he went on, “they look at everything through their befogged glasses, and they think nothing any good which is not English.”

“Such a feeling is necessary to enthusiasm,” replied Norman, suppressing a yawn, “and enthusiasm seems an essential to progress.”

“Therefore you are no patriot.”

“No? why?”

“Because you have no enthusiasm.”

“It is dangerous to judge hastily.”

“Not a bit of it. Hasty judgments are in nine cases out of ten right. As I said, you English are cautious in the wrong place. Besides, your statement that the insular feeling is necessary to enthusiasm is wrong. It may be necessary to fanaticism, which is different from enthusiasm. Real enthusiasm is the outcome of being possessed by a great ideal.”

“Which may be a fad,” suggested Norman.

“A great ideal which is universal in its application, which is wider than nations or sects, which embraces all truth, moral as well as national,” he went on, without noticing the interruption.

“That’s as vague as a cloud,” replied Norman.

“No,” said the other; “not when the ideal becomes embodied in some system.”

“For example?” suggested Norman.

Again the man rested his piercing eyes on Lancaster’s face and hesitated. Evidently here was a man over whom he could exercise no great influence; one who knew when to be silent, and who did not easily lose his head.

“I do not think you quite understand me,” he replied at length; “but in proof of what I said about your race, take yourself as an example. Here are you, evidently a man of wealth and leisure. You have the means and the opportunity of going all over the world, but, like the rest of the English, you stick to these little Islands. I daresay you know your own country almost inch by inch, while I expect you have been to Ireland dozens of times. Meanwhile you have paid only a flying visit to the other countries of the world?” and he waited as if expecting an answer.

“I suppose this is his way of asking me if I’ve been to Ireland before,” thought Norman; “well, it will do no harm to tell him.”

“Is that not so?” he asked presently.

“You are wrong,” replied Norman, “I have never yet been to Ireland, and I’ve spent years in countries other than my own.”

“For pleasure?”

“Yes,” replied Norman, somewhat resenting his freedom in asking questions, although the pleasant smile and soft voice made anger almost impossible.

“But surely you are not going to Ireland for pleasure at this time of the year?” he suggested.

“Yes, I am, purely for pleasure. But the same question might be applicable to yourself. Do you go on the same errand?”

“I do nothing for pleasure,” was the reply, “that is, it is never my motive; yet all I do brings me pleasure.”

“I wish I knew your secret,” laughed Lancaster.

“My secret is easily revealed,” was the reply. “I have my ideal. It is universal, it embraces all truth, and it has become concrete.”

“That seems an impossibility. Pray tell me what it is.”

“You would not pretend to teach Euclid to the lad who had not mastered the elements of arithmetic,” was the reply.

This was evidently said with a purpose. “I am sure he does not mean to be rude,” mused Norman; “the fellow has some meaning in trying to draw me out. He wants to throw me off my guard. Why, I wonder?”

He looked into the stranger’s face. A smile played around the thick, strong lips, a look of eager questioning was in his eyes.

“I think even a cosmopolitan can be cautious in the wrong place,” said Lancaster quietly.

This reply evidently disappointed the other, while it heightened his feelings of respect for his companion. Before he could speak again, however, a young man came up to the table.

“Can I have a word with you, please, father?” he said in low tones. For the first time the stranger’s face flushed, he appeared angry at the interruption, and gave the questioner a look which was not at all pleasant. Nevertheless, he spoke quietly.

“Certainly, I’ll come with you.”

Lancaster looked at the newcomer’s face. It belonged to a young fellow apparently about eight-and-twenty. It was difficult to tell with any degree of certainty, however. He was much muffled, and the lower part of his face was hidden.

He called him “father,” thought the young man, as they walked away together, but if those two are father and son, all Nature is a liar. By Jove! I’ll find out before we get to Ireland; I feel more and more curious about my cosmopolitan friend.

“They questioned the sailors concerning the sea outside.”

Lancaster waited a few minutes longer in the saloon, but his companion did not return; he then went on deck, hoping to see him there. The boat was now out in the open sea, and was tossing like a cork upon the waves. The young man had a difficulty in standing. The day was not yet quite gone, but the dark clouds which hung in the sky increased the gloom of the evening. Presently he saw a sailor.

“You’d better go under, sir,” was his advice.

“Why?”

“It’s a dirty sea, and you might get drenched any minute.”

And as if in fulfilment of his words a huge wave swept over a part of the boat, and a heavy shower of spray fell upon the young man.

“Is no one on deck?” he asked.

“None of the passengers, sir. There was a couple of young chaps who said they was afraid to go below, ’cos it made ’em so ill; but I ’ad to make ’em go, ’cos very likely they’d ’a’ got washed overboard.”

“I’ll just take one turn around,” said Lancaster, “and then I’ll go down again.”

He promenaded the saloon passengers’ end of the boat, but not a soul was to be seen. Indeed, it was not the kind of weather to make people venture on deck. They were sailing in the teeth of the wind, which blew icily cold, and the waves constantly swept over parts of the boat.

“Evidently they are not up here, this father and son,” thought Lancaster; “neither are they in the saloon. I expect they have a private cabin. Well, I’ll go and lie down, and make myself comfortable.”

It was late at night when they reached North Wall, and just as the boat was slowing up to the landing-stage the stranger appeared in the saloon alone.

“My son was not very well,” he said to Lancaster, “so I stayed with him. To what hotel do you go?”

“I really don’t know. Are you acquainted with Dublin?”

“I know nearly every town of importance on the globe,” was the reply. “The most comfortable hotel in Dublin is the Cosmopolitan.”

“Then I’ll go there,” said Norman. “Thank you for mentioning it. Are you staying there?”

“No; my son and I go among friends. I am glad to have met you. Perhaps we may see each other again some time—the world is small.”

“I should be delighted,” replied Lancaster, and he busied himself with his luggage.

Norman Lancaster might fairly be called clever. Not a great man by any means. No pessimist ever is, ever can be. He possessed the possibilities even of greatness, but before those possibilities could ever be realised it was necessary that he should be awakened out of sleep. There is more embryo greatness in the world than we think. The good God has given far more to us than we dream of; but many men do not give Him a chance to work His will. Norman Lancaster was capable of intense feeling, passion; he possessed a nature which, had it been fully aroused a few years before, might have made him a power in the life of England. He might have been an orator, statesman, journalist—almost anything; but for years he had been a cut between an incarnate yawn and a cynic. Had he been aroused to love, to hate, to sympathise; had he possessed faith—faith in the possibilities of mankind, of Providence—he would have thought great thoughts, spoken daring words, done noble deeds. But a part of his nature had been asleep, with the result that he had remained simply a clever man.

Still, he was clever, and, in spite of his seeming indifference, he went around the world with his eyes open. As he drove to his hotel he made several shrewd guesses concerning his travelling companion. In spite of himself, he had been impressed by this large-limbed, strong man. He had a feeling, too, that he should meet him again; but this was only an impression, and impressions did not count for much with him.

As he sat down to a light supper before going into the smoke-room, a man came into the coffee-room and gave an order to a waiter.

“I have just come from Limerick,” he said, in tones loud enough for Lancaster to hear. “I am as cold as a starling and as hungry as a hunter. A good hot meal, if you please.”

The polite waiter helped him as he took off a heavy grey ulster, and took it to a stand outside the door. The stranger took his seat opposite to Lancaster, and then looked carelessly around the room. He was clothed in a tweed suit, of the same colour and material as his ulster, and might have been the son of a well-to-do yeoman, or even a member of the landed gentry of the country.

As Lancaster looked into his face he felt his heart beat faster than was its wont, but he made no motion of any sort.

“Cold for March.”

“Very,” replied Lancaster.

“The snow’s a foot deep down Limerick way. I was fool enough to come on by a slow train, too. I have just arrived from there.”

They remained together for a few minutes, the stranger chatting pleasantly, Norman listening quietly and taking mental notes concerning his companion. He was a good-natured looking fellow, light-haired, and somewhat freckled. He wore a fairly thick moustache, but otherwise was cleanly shaven. He appeared perfectly frank, and spoke with all the characteristic fervour of an Irishman; but he puzzled Lancaster greatly.

“You are going to the smoke-room?” he said, as Norman rose to his feet.

“It is rather late,” was the reply; “but I’ll have a whiff before I go to bed. Good-night.”

“Oh, I’ll see you there in ten minutes,” said the young man, and he attacked the leg of a chicken with much energy.

Lancaster went straight to the smoke-room, and without waiting a second began studying a time-table. Five minutes later he sat back in his chair with a curious smile upon his face. There was no train from Limerick corresponding with the one by which the stranger said he had come. “Why did the fellow tell me that lie?” he thought, as he lit a cigar.

A second later he left the room, and went to the hall door. It was snowing heavily. “A wintry night for March,” he said to the porter.

“Very, sir.”

“I expect I’m your latest visitor to-night?”

“No, sir. A gentleman came a few minutes after you in a cab. He came from Holy Cross way.”

“Oh, I think I saw him. He wore a grey ulster.”

“Yes, sir, the same.”

“Well, I think I’ll go to bed. By the way, I shall possibly go Limerick way to-morrow. In which direction does the station lie?”

“You go over the bridge, sir, in the direction of Trinity College, then——”

“Oh, never mind to-night,” said Lancaster sleepily; “I can find out to-morrow.”

He went back to the club-room again, and began studying a map of Dublin. Holy Cross lay in the opposite direction from Trinity College.

Norman Lancaster smoked quietly for some time, looking steadily into the fire all the while.

“I had my suspicions from the first,” he said presently.

In spite of the lateness of the hour there were several people in the smoke-room. Most of them were talking eagerly. Presently two burly Irishmen came to the fireplace by which Lancaster was sitting, and drew chairs close to the grate.

“It’s jolly cold,” one said, turning to Lancaster.

“Very.”

“I feel like having something hot to drink. Hot punch, a strong whisky cocktail or something, and a quiet game of solo whist.”

The man who spoke looked at Lancaster, but the young man made no response. At that moment his coffee-room acquaintance came up to him. He immediately made room for him beside the fire.

“I hope you feel warmer,” said Lancaster.

“Yes, a bit, but the night grows colder. Won’t you join me in something to drink?”

“I don’t mind,” said the young man; nevertheless, he made up his mind to take nothing.

“Join with us,” said the burly Irishmen. The young fellow looked at Lancaster, who nodded assent.

For a few minutes they talked on various questions, Lancaster joining but seldom. The waiter soon appeared with spirits and other condiments necessary to make the especial drink ordered. Norman noticed that the young fellow looked around rather anxiously, but made no demur when a large quantity of drink was poured out for him.

“You are a stranger to Ireland, I expect?” he said.

“Why?”

“English people seldom come to Ireland,” was the reply. “The general impression is that we are a nation of cut-throats, whereas we are quite the reverse. Personally I like English people.”

“This is very clumsy,” thought Lancaster, “but what next?”

“Does Ireland feel strange to you?”

“It does somewhat.”

“I was never out of Ireland,” said the other, “but I know my country well. If I can be of any service to you while you are here I shall be very glad.”

“That is very kind of you. I shall be glad to take advantage of your offer. I wish to visit several parts of the country. I also wish to get an entrée into some institutions; perhaps you can help me.”

“Easily, easily. Where would you like to go?”

“I’ve got the names in my notebook,” replied Lancaster aloud. To himself he said, “The fellow’s a fool.”

Half an hour later the smoke-room was empty save for the four men by the fire. Lancaster had not tasted the punch in his glass; the young man claiming to come from Limerick, however, had allowed his to be refilled more than once. The drink, moreover, was getting into his head.

The waiter stood by yawning, and occasionally looking at the clock.

“Is everybody gone to bed except ourselves, waiter?” said one of the Irishmen.

“Yes, sir,” replied the fellow eagerly. Evidently he longed for sleep.

“And nobody else will come here to-night?”

“No, sir.”

“What do you say to a game of cards, gentlemen?” he said, looking towards Lancaster; “we are four of us. We shall make a nice little party, and I don’t feel a bit sleepy.”

Lancaster nodded his head carelessly, and turned towards the man from Limerick.

“What do you say?” he asked of him.

“Oh, certainly—if you do,” replied the young man, smoothing his moustache.

“If that moustache is not false, put me down for an ass,” thought Lancaster. “The fellow has drunk more than is good for him, too. Well, I fancy I shall know a thing or two before the night is over.”

They commenced playing. Lancaster was no gambler, but he had a purpose to serve, therefore he made no objection when the Irishmen suggested that the counters should represent a certain amount of money. The man from Limerick looked frightened, but made no objection.

An hour later Lancaster rose with a yawn.

“I’ve lost enough,” he said.

“But not so much as I,” giggled the young man from Limerick. “I—I am stone broke, but who cares? who cares? There’ll be a jolly row, but who cares? Not I! not I! Let old Ritzoom say what he pleases. What do I care? Hip, hip hoor——” His voice died away in a drunken hiccup.

“But you had better pay up what you owe?” suggested one of the men who had seemed so eager to play.

“Certainly,” said the other; “that’s the proper thing to do.”

“All right, certainly,” he giggled; “but I—I don’t possess so much—I—I——” and he sat down like one in a stupor.

The burly Irishmen began to bluster, whereupon the young fellow muttered incoherently.

“He scarcely understands now how matters stand,” said Lancaster. “I suggest that he gives you an I.O.U. for the amount to-night, and to-morrow morning you can discuss the matter.”

“Yes, yes,” cried the other with evident relief. “I’ll give you I.O.U.—promising to pay you to-morrow. Old Ritzoom will make it right—that’s it, that’s it.”

Evidently he was trying to understand his position. He read the I.O.U. with great solemnity, and declared that one of the words was not spelt correctly. Presently he seized a pen and signed his name, “Father Relly.”

“Father Relly,” cried the man in whose name the I.O.U. had been made—“is that your name?”

“No, no, I’m drunk, that’s what I am. It’s James Relly. Make out another, and I’ll sign it—prop’ly.” This he said like one afraid.

When the affair was arranged, however, he sank back in the chair and seemed unable to move.

“By gosh, who is he?” asked one of the Irishmen.

“Dunno,” replied the other with a laugh; “but I think we’ll get our money.”

“Anyhow, he must be got to bed,” said Lancaster.

“Yes, but I’ll take jolly good care he does not get away in the morning until I’ve had this out with him,” replied the man, patting the piece of paper which the young fellow had signed.

When Lancaster got to bed he called to mind all that had happened through the day. He remembered many of the words which the young fellow, claiming to come from Limerick, had spoken.

“I think it’s pretty plain,” thought the young man. “If ever luck played into a fellow’s hands it has played into mine; but I haven’t quite cleared the ground yet. I have an idea that, to-morrow, matters will develop somewhat. The thing that puzzles me is that Father Ritzoom should have trusted that young chap to play the spy. He’s not at all fitted for the job. But to-morrow will tell.”

Next morning he was awakened by some one knocking at his door, and he heard the angry voices of men in the corridor outside.

Norman lancaster began to dress rapidly, and on looking at his watch he found that it was after ten o’clock.

“It is easy to understand what’s up,” he thought, as he listened to the angry voices. “Our friend from Limerick has realised his difficulties, and this pair of Irishmen are making it warm for him.”

“What can I do to serve you, gentlemen?” he said aloud as he opened the door.

The three men, who had been his companions the previous night, came in, two of them blustering and vehement, the third pale to the lips.

“This fellow states that an unfair advantage was taken of him last night,” said one of the burly Irishmen presently. “I appeal to you, you who lost a trifle, whether everything was not fair and above board.”

“I—I have no recollection of losing so—so much, or—or of signing that paper,” said the young fellow tremblingly.

Whereupon many angry words followed, the older men protesting and threatening, the young man feebly declaring that he was ignorant of the obligations under which he lay.

“I do not possess so much money,” he said at length. “I cannot get it. It would ruin me if I were to try.”

“You said that some one by the name of Ritzoom would help you,” said one. “Go to Ritzoom and get it, or we will.”

“Ritzoom! did I mention his name?” he cried, and his voice trembled with evident fear.

“That you did,” was the answer. “I have an idea that I can find out who Ritzoom is, and, by Gad! I will if this matter isn’t squared.”

“Look you,” said Lancaster at length, “you are all strangers to me. I never saw any one of you until yesterday, but I think the affair can be managed. Will you two kindly leave me with this young man for half an hour, and perhaps at the end of that time I shall be able to suggest some amicable arrangement?”

“But you will not leave the hotel?”

Lancaster gave the man a look which evidently made him feel uncomfortable. He stammered something about “not meaning to offend,” and the two walked hurriedly away.

A few moments later the two young men were alone together.

“Can you help me?” said the younger man eagerly. “Can you get me out of this scrape? If you can, I—I, God helping, there’s nothing I will not do for you!”

Lancaster went to the door and fastened it. “I wish to know first why you told me a lie yesterday?” he said.

“A lie!” stammered the other.

“A lie,” repeated Lancaster. “You came over with me yesterday from Holyhead, and yet you told me you came from Limerick. You spoke as though you owned property in that district, whereas you are a priest, and possess no property at all. Evidently you were instructed to dog my footsteps. I saw that by the way you acted. Now tell me the meaning of this? Your name is Father Relly, and, if I mistake not, you are a Jesuit.”

“How—how do you know this?” he stammered, the perspiration standing in thick drops on his forehead.

“I do know it,” replied Lancaster, “and the man who was with you on the boat yesterday is Father Ritzoom.”

Relly sat down on the bed like one stunned.

“Now, mind,” continued Lancaster, “I am no enemy of yours; rather, I am desirous of helping you out of the scrape into which you have got with these countrymen of yours. But before I do so I wish to know your design concerning me. Why did Ritzoom tell you to watch me?”

Relly placed his hand upon his moustache, as if in denial of Lancaster’s statement.

“That moustache is false,” said Lancaster. “Yesterday the lower part of your face was muffled, so I suppose you thought I should not recognise you again. Ritzoom thought so, too, or he would never have sent you to spy upon me. Now be frank with me.”

“I dare not. I dare not,” replied Relly.

“Why?”

“Because I promised, I promised—God help me, I promised!”

Lancaster pitied the young man, but he had a purpose in view. He believed that his acquaintance with Relly would assist him, provided he were careful. It was for this purpose he encouraged his advances the previous evening.

“You are in a sad mess, though,” he suggested.

“I know I am. I was mad. I—I—the breath of freedom, the feeling that I was a man among men for a few hours was too much for me. I was spoken to as a man, and not as a——”

He stopped suddenly, and his lips trembled like those of a boy, while the tears welled up in his eyes.

Lancaster looked at him steadily. Relly’s face was as free from guile as that of a young girl. That he was kind-hearted and true no one could doubt. He was warm-blooded and impulsive, too; strong in his likes and dislikes. Jesuit priest he might be, but no amount of training could make him one at heart. By what means he had been led to take the vows of his order Lancaster knew not, but he knew he was totally unfitted for such a calling.

“Look here, Father Relly,” he said at length, “is this squabble with these men serious? Can they harm you? Do you dread Ritzoom having any knowledge of the matter?”

“He seems to read me like a book,” replied the other, “but—oh, I would rather die than that he should know. Then I must have been drunk! Oh, the disgrace of it, the shame of it!”

Lancaster took his pocket-book from his coat, from which he extracted two Bank of England notes. “There,” he said quietly, “take these to those men, and they will give you that incriminating paper back. Or stay, I’ll go with you.”

Relly took the notes and read them eagerly. “Do you mean it, do you mean it?” he cried.

“Of course I do. There, I’ll be ready to go with you in two minutes.”

The young priest caught Lancaster’s hand with all the fervour of a lover. “Oh, bless you, bless you, my friend,” he cried; “if there is anything I can do to serve you, I——” He stopped confusedly. Perhaps he remembered that he had just refused to tell Lancaster why he had been spying upon him.

“That is all right,” said Lancaster; “now let us go to these men.”

They had not reached the end of the corridor before they came upon the worthy couple. Evidently they were determined not to let Relly leave the hotel before paying the gambling debt. Possibly they had suspicions as to his calling, and believed that their money was safe, even although they had no legal claim to it.

“The drawing-room is empty,” said Lancaster, leading the way to it. The men followed, evidently wondering what the upshot would be.

“Whether you are a pair of sharpers or no, I know not,” said Lancaster quietly, whereupon both began to protest with great vehemence, also to threaten to take proceedings for defamation of character. “Well, you may be honest men,” laughed the young man, “anyhow, here is your money. But remember, if a word concerning this matter goes beyond ourselves I shall take the trouble to find out who and what you are.”

“We are gentlemen,” they protested, “and as gentlemen we should not think of mentioning such a matter. We will take our solemn oath on that.”

“Very well,” replied Lancaster; “as for this I.O.U., it’s done with,” and he threw it in the fire. “I remember your names and your faces. I fancy I have seen you before, but I do not wish to see you again. Good morning.”

A few minutes later he saw them get into a cab and drive away.

“There,” said Lancaster with a yawn, “that’s done with. Now I’ll get some breakfast.”

He did not speak a word to Father Relly, but found his way into the coffee-room, and sat down to his morning meal with a good appetite. He saw the young priest take a seat at another table, but seemingly he took no notice. Presently Lancaster finished his meal and prepared to leave the room. Before he reached the door the young priest had caught his arm.

“I must speak to you alone,” he said earnestly; “I—I cannot allow——” then he stopped confusedly.

Lancaster had expected this. He had been summing up Relly’s character all the morning, and he reckoned upon the young fellow’s impulsive nature.

“Have you a private room which I could have for half an hour?” he said to the hotel manager, who happened to be near.

A few minutes later he was again closeted with the young priest.

“It’s no use, I must tell you,” said Relly. “Promise or no promise, I cannot go on acting a part against one who has been so kind. You have been so generous that you have actually befriended your enemy.”

“Nonsense,” said Lancaster with a smile. “You are not my enemy. You could be the enemy of no man.”

“You think I am a fool,” said the other; “I am, I know I am. All the same, you know I was trying to thwart your purposes.”

“No, you are not a fool. You are simply an honest young fellow. You are totally unfitted for the work imposed upon you. You are too sincere to be a spy or a diplomat, that is all. Therefore you bungled terribly.”

“Yes, yes—that is, do you think so?”

“I am sure of it; what puzzles me is that Ritzoom should have appointed you to an office for which you are entirely unfitted.”

“Let me tell you——” cried the young priest eagerly.

“Tell me nothing,” replied Lancaster. “You will be sorry afterwards. Besides, I think I know all you would say.”

“What do you know?”

“Well, Ritzoom thinks I am engaged in a work which may prove detrimental to the objects of his life. He is not certain, and he appointed you to find out. Ritzoom may be right or wrong in his conjectures concerning me, but I cannot understand how a fellow of his penetration commissioned such a simple, honest, transparent fellow as you as his agent.”

“It was by my desire. Oh, I wanted to show my earnestness for work! It is long years since I lived in the world. I—I have been preparing for my vocation, during which time I have not come into contact with human beings. They have simply been those of my order. I thought my training had fitted me for almost anything. So when Father Ritzoom told me he should like to know what your plans were, I begged to be allowed to find out.”

“And he?”

“He consented.”

Lancaster reflected a minute. He fancied he saw the working of Ritzoom’s brain. He believed that the older priest desired rather to test this young man than to discover anything concerning himself.

“Well, go on,” he said.

“Yes; well, I dressed myself as a man of the world. I recalled to mind the life I lived before—I—I ceased to be a man and became a Jesuit. I became intoxicated. It was glorious to feel as others might feel. For once I felt that watchful eyes no longer rested on me. It is true I was acting a part, but it was the part of a full-lived man. I lived in a new world. I could think, feel, act as others might. It was too much for me. In my desire to appear a man of the world I forgot myself. It is years since I drank spirits, and I forgot the effect it might have on me. I thought you would have no suspicions concerning me if I drank freely. And then—you know what followed.”

“You will have to give a report to Father Ritzoom,” said Lancaster presently.

“Yes.”

“Well?”

“I cannot tell him.”

Lancaster laughed. “There will be no need,” he said.

“Why?”

“Because he knows.”

“You have not told him?”

“There is no need. Do you think you have not been watched? Ritzoom’s desire to test you was as great as his wish to find out my purpose in coming to Ireland. Moreover, I venture to make a prophecy. You will never be entrusted with this kind of work again.”

“Then what do you think I ought to do?”

“Tell him exactly what has taken place.”

“But——”

“Oh, you need not fear. He will not be surprised. As you say, he reads you like a book, and will be prepared for all contingencies.”

“But—but are you what—what he thinks you are?” asked Relly eagerly.

Lancaster looked at him keenly. “I believe he is more a Jesuit than I imagined, after all,” he thought.

“What does he think I am?” he said aloud.

“I do not know. He told me nothing, except that you were an enemy to our faith. Are you?”

“I am a Protestant,” said Lancaster, “therefore I must be an enemy to your faith.”

The young priest crossed himself. “I will pray for you,” he said.

Lancaster laughed. “Thank you,” he replied.

“Yes, I will pray for you,” he said earnestly; “believing, as you do, you will doubtless think I need to pray for myself. Still, I will pray for you, pray that you may be snatched from the burning. One of your evident goodness and kindness of heart should be. Moreover, if I can help you at any time, I will—oh, so gladly!”

He seemed more calm now and spoke less vehemently.

“Thank you again,” said Lancaster; “but suppose I should desire to claim the fulfilment of your promise, where should I find you?”

He took a card from his pocket. “As far as I know at present, I shall be at that address during the next few weeks.”

Lancaster read the card. On it was printed the name of the college for novices where Jack Gray was immured. Not a muscle of his face moved, however, as he read the card.

“And Father Ritzoom,” he said, “where will he be?”

“I do not know,” said the young priest.

“And now,” said Lancaster, “will you continue to dog my footsteps?”

“No; I shall go back to Father Ritzoom,” was the reply.

Lancaster felt that the young man was changing. He was becoming a priest again. The older man rose to his feet. “You will want to go back to your superior at once, I expect,” he said, “and I will not detain you. Perhaps we shall meet again. I think we shall.”

“I shall be at the college.”

Lancaster laughed.

A few minutes later, the young priest left the hotel, while Lancaster pondered over the way matters had developed.

“Relly is more a Jesuit than I thought,” he said presently, “but he has a heart, and he’s an Irishman. No amount of training can destroy that fact and it may be that my money is not badly invested.”

Meanwhile, Relly found his way to a house which adjoined a Roman Catholic Church, and before long was ushered into a scantily-furnished room. No carpets covered the floors, and the only articles visible there were three chairs, a table, and a small kneeling-desk, over which hung a crucifix.

On one of the chairs, which was drawn close to the table, sat the man with whom Lancaster had travelled the previous day. He was utterly metamorphosed. Instead of the pilot coat, he wore a black soutane, a loose garment which hung around his body like a robe. On his head was the ordinary biretta of an ecclesiastic. He went on writing as Relly entered, although he was evidently aware of his presence.

“Sit down,” he said presently.

The young priest sat down.

A few minutes later he threw down his pen and looked up. “Well?” he said suddenly.

“I have failed, father, grievously failed.”

Ritzoom did not move a muscle of his face or evince any surprise.

“In what way?”

“In every way.”

“Explain.”

“He saw through my disguise. He associated me with you.”

“How do you know?”

“I sat at the same table with him. I said I had just come from Limerick, as suggested by you. When he left the room and had gone into the smoke-room, I asked a waiter to follow him and tell me what he was doing.”

“Yes; well?”

“He was studying an Irish time-table. The waiter said he was looking at the trains on the Limerick line. There is no train from Limerick so late at night.”

“I was at fault,” said Father Ritzoom, after hesitating a few seconds. “Consequently, he was on his guard?”

“Yes.”

The priest wrote a few lines in his notebook, then he fixed his black, piercing eyes on Relly’s face.

“The best of us are liable to failure, my brother,” he said; “but tell me the rest of your experiences.”

The young priest hesitated. He had begun his report by twisting the truth. It was Lancaster who had told him about the trains.

“I found him to be a very clever man,” he said presently. “He knew who you were. He had recognised you.”

“You are sure of that?”

“Quite sure of it.”

“Tell me how?”

“He said he had seen me speaking with Father Ritzoom on the boat.”

Ritzoom continued to look steadily at the younger man, and a smile, half sad, half cynical, played around his mouth. He did not know so much as Relly feared, but he knew a great deal. He seemed to be hesitating as to whether he should question him further, when a knock came at the door, and a boy, who acted as porter, mentioned a name.

“Ah!” he said, “our interview must end here, my brother. As you say, you have not been successful, and yet you have revealed more to me than you think. The fact of his recognising me tells everything. You must change your garments, and get back to your old work. This experience will have added to your education, and, I trust, to your usefulness. I am glad that you have been so frank; always remember that in dealing with me you will do well to be perfectly open.”

There was a curious intonation in his voice, as well as a warning look in his eyes, as he spoke.

“Good-day, my brother; I have an impression that you will meet Norman Lancaster again.” He said this as he walked out of the room. When he had closed the door, and had gone some distance along the corridor, he stopped, as though he would go back again. A second later, however, he went on his way.

“No, I have dealt wisely with the fellow,” he said. “He is not fit for any delicate work; he never will be. His mind is not cast in the necessary mould, and he’s an impulsive Irishman. But I had best let him be; I shall be able to make most use of him in that way. Had he confessed everything I should have had no hold upon him; now, by careful dealing and watching, I think I may——Oh, but he is utterly unfitted for the work of our order! How in the world can the bon Dieu make such fools?”

As for Father Relly, he heaved a deep sigh of relief when his superior had gone.

“After all, I spoke to him not as a confessor, but as a brother priest,” he said, as he went away to another room in order to change his garments.

The next day Norman Lancaster stood near the gates of an old building, seventy miles from Dublin. It was the Institution for Novitiates where Jack Gray had spent the last two years. The place was four miles distant from a railway station, and, but for another house about a mile away, no signs of human habitation were visible. Spring had only just begun to make its appearance, the trees were still bare, the hedgerows were only just beginning to show their bursting life, but the country side was very beautiful. In the valley near him a clear river sang its way towards the sea; on every hand the country was finely wooded. It would be difficult to conceive of a spot more charmingly situated; it would be just as difficult in a civilised country to find a neighbourhood more forsaken by living beings.

Norman Lancaster had tried to formulate plans for entering the old castellated building which stood on the wooded heights above him, had tried to devise means whereby he might be able to converse with Jack Gray. He had been utterly unsuccessful. He was sure that Father Ritzoom must have seen him with Carelton in London; he was just as sure that, by means of the numerous agencies at his command, he had discovered his mission, and would, therefore, use means for thwarting him in his purposes. But the young man had no idea of giving up. The love for adventure had been aroused within him, and that dogged perseverance which is peculiar to the English race, and which has helped to make our land what it is, was a strongly marked trait of his character.

I do not think he knew much about fear, and he appeared to be as careless and listless as usual as he stood near the gates which opened up the way to the house he desired to enter. He had adopted no disguise; he knew the futility of such devices where a man like Father Ritzoom was concerned. One thing he knew. The Jesuits did not like scandal. He was well aware, moreover, that the Roman Church desired to stand well with the English people, that it was the great desire of its adherents to win back the English race to the Roman fold. For that reason they would do much to keep any reports, which might harm their cause, from circulating in English newspapers.

“It is a funny business,” thought Lancaster; “and if ever a fellow was engaged in a wildgoose chase, I am that fellow. But, by Jove! I believe I enjoy it.”

Interested as he was in his mission, he took note of the rare beauty of the situation, and mentally congratulated the monks on their choice of a place of residence.

“After all, it must be rather a fine experience to become imbued with the rules and constitutions of Ignatius Loyola,” he thought. “I shall be mightily glad to have a talk with Jack—if I can,” and he laughed as he carefully relit his cigar.

He rang boldly at the door of the old house, and a few seconds later he heard steps along an uncarpeted hall. A young man in monk’s attire opened the door and asked him his business.

“I should like to see a young man named Gray, Jack Gray,” replied Norman quietly. “He came here about two years ago.”

“Have you a letter of recommendation?” asked the young man.

“No, but I am an old college chum of his brother.”

“Will you come in?”

Lancaster entered the building and followed his guide into a barely-furnished room. Arrived there, the young priest left him.

“Everything is orderly here,” thought Norman; “no noise, no disturbances. Ah, but this will be a beautiful spot in summer!”

He looked around the room and noted the extreme simplicity of all the arrangements. “No carpets, not a comfortable chair in the place, and not a couch of any sort. The pictures are hideous daubs, while that crucifix above the kneeling-desk is enough to make a nervous man shudder. The place is as cold as a tomb, too,” and the young man almost shivered as he buttoned his coat more tightly around him.

A minute later the door was opened and a priest of about fifty years of age entered. He was a quiet, inoffensive-looking man, with large, mild eyes and a somewhat ruddy face. All his actions were suggestive of indecision, as though he could never fully make up his mind what to do. In his hand he held a small black book.

“You have come for confession?” he said in a low tone.

“No,” said Norman, “I have come to have a talk with a fellow whom I used to know as Jack Gray. I do not know whether he has a new name now. He came here about two years ago.”

“He is a novice, and it is arranged for him to take vows in a fortnight from now—at least, I expect so.”

“Still, there is no reason why I should not see him, I suppose?”

“It is not our desire that the minds of our novices should be disturbed by worldly influences,” said the priest; “and we like, as far as possible, to allow the grace of God to be unhindered.”

He said this in a hesitating way and rubbed his hands nervously. Norman looked at his face keenly and tried to read the man. He saw that the hesitation was only seeming. Behind those mild, large eyes was a great deal of quiet strength.

“I will take your message to him,” he continued; “I will ask him any questions you may desire.”

“I should like to see him alone if I may,” persisted Lancaster. “There are some things in life which one does not care to speak about indiscriminately.”

He thought it best to be free of speech, for he felt sure that Father Ritzoom had been there and prepared the man for his visit. He was beginning to realise something of the unknown forces of the Jesuit order. By what means the purpose of his visit had been discovered he could not imagine, but he knew that the true Jesuit mind was of the most subtle nature.

“There is no secret between the superior and the novice,” replied the priest; “there should not be. Is not that your opinion?”

“And you are the superior?”

“Yes. The work is not of a kind that I care for. I like quiet, freedom from responsibility, solitary communion. But what of that? I am here, I have been here for thirty years.”

Norman began to be grave. There was something awesome in being shut off from the world for thirty years.

“Then you refuse to allow me to see Jack Gray?”

“I do not say that. I only wish to know that you do not desire to unhinge his mind. According to the ninth—one of the most important—of the rules in the Constitutions of St. Ignatius, it is incumbent that all novices shall beware of the devil’s attempts to unsettle them in their holy vocation, and to fill their souls with sadness and trouble.[A] I should miserably fail in my duties as superior if I were to allow one of my children to be tempted of the devil.”

“But Jack is still a novice and, I suppose, a free man?”

“In a degree, yes.”

“But surely your faith in your religion is very small if you are afraid of a man seven-and-twenty years of age hearing of any matter whatever?”

“Even our blessed Lord prayed, ‘Lead us not into temptation.’ ”

“He also prayed not that His disciples should be taken out of the world, but that they should be kept from the evil of the world.”

The superior looked at Lancaster wonderingly.

“ ‘Kept from the evil.’ Yes,” he repeated. “Do you desire to do the young man harm?”

“No, I desire to do him good.”

“Therefore there is no reason why you should not tell me the message you wish to give him?”

“We see things differently, perhaps,” replied Lancaster. “But I have been told that Jesuits desire to appeal to reason; that they wish to do everything openly—in the light of day; that there is nothing they wish to hide from the world.”

“Oh, that is true—quite true. We have no secrets, none at all.”

“So a Jesuit priest told me once before,” said Norman; “therefore it strikes me as peculiar, aye, and would appear very strange to the British public, if a University graduate who has become a novice was not allowed to see an old friend of his brother.”

The superior seemed to be in deep thought for a few minutes.

“You shall see him,” he said presently; “I will send him to you—that is, if I can arrange for——” He did not finish the sentence; it would seem as though the proviso he hinted at was intended as a kind of justification should he choose to alter his mind.

The superior left the room and found his way into one of the many rooms of the great house. As he entered he saw a young man kneeling before a crucifix. The priest waited a few seconds and then spoke.

“My brother.”

“Yes, father.”