* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Vol 1, Issue 4

Date of first publication: 1865

Author: John Townsend Trowbridge, Gail Hamilton and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Feb. 9, 2017

Date last updated: Feb. 9, 2017

Faded Page eBook #20170211

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. I. | APRIL, 1865. | No. IV. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1865, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

hilip went home alone from the party, out of

sorts with himself, angry with Azalia, and boiling

over with wrath toward Paul. He set his teeth together,

and clenched his fist. He would like to

blacken Paul’s eyes and flatten his nose. The

words of Azalia—“I know nothing against Paul’s

character”—rang in his ears and vexed him. He

thought upon them till his steps, falling upon the

frozen ground, seemed to say, “Character!—character!—character!”

as if Paul had something which he had

not.

hilip went home alone from the party, out of

sorts with himself, angry with Azalia, and boiling

over with wrath toward Paul. He set his teeth together,

and clenched his fist. He would like to

blacken Paul’s eyes and flatten his nose. The

words of Azalia—“I know nothing against Paul’s

character”—rang in his ears and vexed him. He

thought upon them till his steps, falling upon the

frozen ground, seemed to say, “Character!—character!—character!”

as if Paul had something which he had

not.

“So because he has character, and I haven’t, you give me the mitten, do you, Miss Azalia?” he said, as if he was addressing Azalia.

He knew that Paul had a good name. He was the best singer in the singing-school, and Mr. Rhythm often called upon him to sing in a duet with Azalia or Daphne. Sometimes he sang a solo so well, that the spectators whispered to one another, that, if Paul went on as he had begun, he would be ahead of Mr. Rhythm.

Philip had left the singing-school. It was dull music to him to sit through the evening, and say “Down, left, right, up,” and be drilled, hour after hour. It was vastly more agreeable to lounge in the bar-room of the tavern, with a half-dozen good fellows, smoking cigars, playing cards, taking a drink of whiskey, and, when it was time for the singing-school to break up, go home with the girls, then return to the tavern and carouse till midnight or later. To be cut out by Paul in his attentions to Azalia was intolerable.

“Character!—character!—character!” said his boots all the while as he walked. He stopped short, and ground his heels into the frozen earth. He was in front of Miss Dobb’s house.

Miss Dobb was a middle-aged lady, who wore spectacles, had a sharp nose, a peaked chin, a pinched-up mouth, thin cheeks, and long, bony fingers. She kept the village school when Paul and Philip were small boys, and Paul used to think that she wanted to pick him to pieces, her fingers were so long and bony. She knew pretty much all that was going on in the village, for she visited somewhere every afternoon to find out what had happened. Captain Binnacle called her the Daily Advertiser.

“You are the cause of my being jilted, you tattling old maid; you have told that I was a good-for-nothing scapegrace, and I’ll pay you for it,” said Philip, shaking his fist at the house; and walked on again, meditating how to do it, his boots at each successive step saying, “Character! character!”

He went home and tossed all night in his bed, not getting a wink of sleep, planning how to pay Miss Dobb, and upset Paul.

The next night Philip went to bed earlier than was usual, saying, with a yawn, as he took the light to go up stairs, “How sleepy I am!” But, instead of going to sleep, he never was more wide awake. He lay till all in the house were asleep, till he heard the clock strike twelve, then arose, went down stairs softly, carrying his boots, and, opening the door, put them on outside. He looked round to see if there was any one astir; but the village was still,—there was not a light to be seen. He went to Mr. Chrome’s shop, stopped, and looked round once more; but, seeing no one, raised a window and entered. The moon streamed through the windows, and fell upon the floor, making the shop so light that he had no difficulty in finding Mr. Chrome’s paint buckets and brushes. Then, with a bucket in his hand, he climbed out, closed the window, and went to Miss Dobb’s. He approached softly, listening and looking round to see if any one was about; but there were no footsteps except his own. He painted great letters on the side of the house, chuckling as he thought of what would happen in the morning.

“There, Miss Vinegar, you old liar, I won’t charge anything for that sign,” he said, when he had finished. He left the bucket on the step, and went home, chuckling all the way.

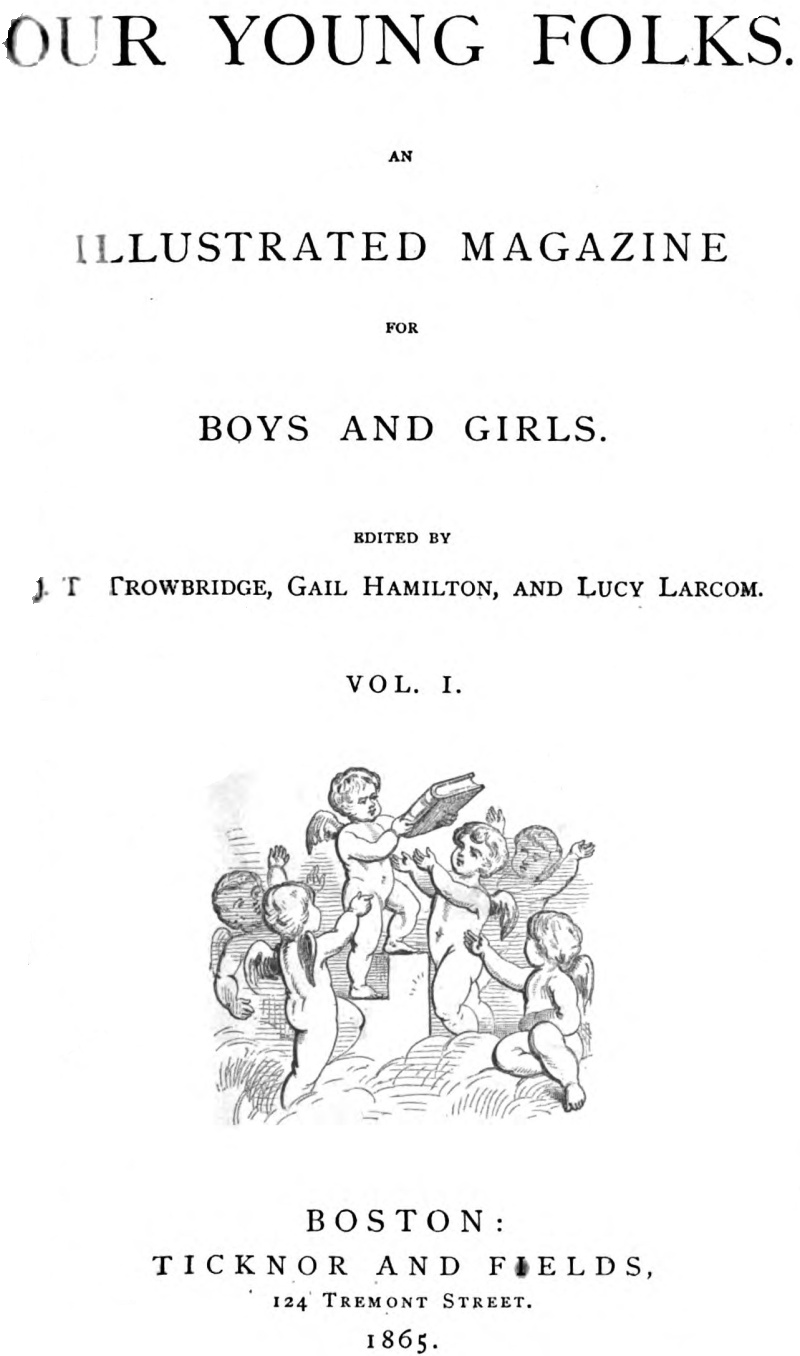

In the morning Miss Dobb saw a crowd of people in front of her house, looking towards it and laughing. Mr. Leatherby had come out from his shop; Mr. Noggin, the cooper, was there, smoking his pipe; also, Mrs. Shelbarke, who lived across the street. Philip was there. “That is a ’cute trick, I vow,” said he. Everybody was on a broad grin.

“What in the world is going on, I should like to know!” said Miss Dobb, greatly wondering. “There must be something funny. Why, they are looking at my house, as true as I am alive!”

Miss Dobb was not a woman to be kept in the dark about anything a great while. She stepped to the front door, opened it, and, with her pleasantest smile and softest tone of voice, said: “Good morning, neighbors; you seem to be very much pleased at something. May I ask what you see to laugh at?”

“Te-he-he-he!” snickered a little boy, who pointed to the side of the house, and the by-standers followed his lead, with a loud chorus of guffaws.

Miss Dobb looked upon the wall, and saw, in red letters, as if she had gone into business, opened a store, and put out a sign,—“MISS DOBB, Lies, Scandal, Gossip, Wholesale and Retail.”

She threw up her hands in horror. Her eyes flashed; she gasped for breath. There was a paint-bucket and brush on the door-step; on one side of the bucket she saw the word Chrome.

“The villain! I’ll make him smart for this,” she said, running in, snatching her bonnet, and out again, making all haste towards Squire Copias’s office, to have Mr. Chrome arrested.

The Squire heard her story. There was a merry twinkling of his eye, but he kept his countenance till she was through.

“I do not think that Mr. Chrome did it; he is not such a fool as to leave his bucket and brush there as evidence against him; you had better let it rest awhile,” said he.

Mr. Chrome laughed when he saw the sign. “I didn’t do it, I was abed and asleep, as my wife will testify. Somebody stole my bucket and brush; but it is a good joke on Dobb, I’ll be blamed if it isn’t,” said he.

Who did it? That was the question.

“I will give fifty dollars to know,” said Miss Dobb, her lips quivering with anger.

Philip heard her and said, “Isn’t there a fellow who sometimes helps Mr. Chrome paint wagons?”

“Yes, I didn’t think of him. It is just like him. There he comes now, I’ll make him confess it.” Miss Dobb’s eyes flashed, her lips trembled, she was so angry. She remembered that one of the pigs which Paul painted, when he was a boy, was hers; she also remembered how he sent Mr. Smith’s old white horse on a tramp after a bundle of hay.

Paul was on his way to Mr. Chrome’s shop, to begin work for the day. He wondered at the crowd. He saw the sign, and laughed with the rest.

“You did that, sir,” said Miss Dobb, coming up to him, reaching out her long hand and clutching at him with her bony fingers, as if she would like to tear him to pieces. “You did it, you villain. Now you needn’t deny it; you painted my pig once, and now you have done this. You are a mean, good-for-nothing scoundrel,” she said, working herself into a terrible passion.

“I did not do it,” said Paul, nettled at the charge, and growing red in the face.

“You are a liar; you show your guilt in your countenance,” said Miss Dobb.

Paul’s face was on fire. Never till then had he been called a liar. He was about to tell her loudly, that she was a meddler, tattler, and hypocrite, but he remembered that he had read somewhere, that “he who loses his temper loses his cause,” and did not speak the words. He looked her steadily in the face, and said calmly, “I did not do it,” and went on to his work.

Weeks went by. The singing-school was drawing to a close. Paul had made rapid progress. His voice was round, rich, full, and clear. He no longer appeared at school wearing his grandfather’s coat, for he had worked for Mr. Chrome, painting wagons, till he had earned enough to purchase a new suit of clothes. Besides, it was discovered that he could survey land, and several of the farmers employed him to run the lines between their farms. Mr. Rhythm took especial pains to help him on in singing, and before winter was through he could master the crookedest anthem in the book. Daphne Dare was the best alto, Hans Middlekauf the best bass, and Azalia the best treble. Sometimes Mr. Rhythm had the four sing a quartette, or Azalia and Paul sang a duet. At times, the school sang, while he listened. “I want you to learn to depend upon yourselves,” said he. Then it was that Paul’s voice was heard above all others, so clear and distinct, and each note so exact in time that they felt he was their leader.

One evening Mr. Rhythm called Paul into the floor, and gave him the ratan with which he beat time, saying, “I want you to be leader in this tune; I resign the command to you, and you are to do just as if I were not here.” The blood rushed to Paul’s face, his knees trembled; but he felt that it was better to try and fail, than be a coward. He sounded the key, but his voice was husky and trembling. Fanny Funk, who had turned up her nose at Mr. Rhythm’s proposition, giggled aloud, and there was laughing around the room. It nerved him in an instant. He opened his lips to shout, Silence! then he thought they would not respect his authority, and would only laugh louder, which would make him appear ridiculous. He stood quietly and said, not in a husky voice, but calmly, pleasantly, and deliberately, “When the ladies have finished their laughter we will commence.” The laughter ceased. He waited till the room was so still that they could hear the clock tick. “Now we will try it,” said he. They did not sing it right, and he made them go over it again and again, drilling them till they sang it so well that Mr. Rhythm and the spectators clapped their hands.

“You will have a competent leader after I leave you,” said Mr. Rhythm. Paul had gained this success by practice hour after hour, day after day, week after week, at home, till he was master of what he had undertaken.

The question came up in parish meeting, whether the school should join the choir? Mr. Quaver and the old members opposed it, but they were voted down. Nothing was said about having a new chorister, for no one wished to hurt Mr. Quaver’s feelings by appointing Paul in his place; but the school did not relish the idea of being led by Mr. Quaver, while, on the other hand, the old singers did not mean to be overshadowed by the young upstarts.

It was an eventful Sunday in New Hope when the singing-school joined the choir. The church was crowded. Fathers and mothers who seldom attended meeting were present to see their children in the singers’ seats. The girls were dressed in white, for it was a grand occasion. Mr. Quaver and the old choir were early in their places. Mr. Quaver’s red nose was redder than ever, and he had a stern look. He took no notice of the new singers, who stood in the background, not daring to take their seats, and not knowing what to do till Paul arrived.

“Where shall we sit, sir?” Paul asked, respectfully.

“Anywhere back there,” said Mr. Quaver.

“We would like to have you assign us seats,” said Paul.

“I have nothing to do about it; you may sit anywhere, and sing when you are a mind to, or hold your tongues,” said Mr. Quaver, sharply.

“Very well; we will do so,” said Paul, a little touched, telling the school to occupy the back seats. He was their acknowledged leader. He took his place behind Mr. Quaver, with Hans, Azalia, and Daphne near him. Mr. Quaver did not look round, neither did Miss Gamut, nor any of the old choir. They felt that the new-comers were intruders, who had no right there.

The bell ceased its tolling, and Rev. Mr. Surplice ascended the pulpit-stairs. He was a venerable man. He had preached many years, and his long, white hair, falling upon his shoulders, seemed to crown him with a saintly glory. The people, old and young, honored, respected, and loved him, for he had grave counsel for the old, kind words for the young, and pleasant stories for the little ones. Everybody said that he was ripening for heaven. He rejoiced when he looked up into the gallery and saw such a goodly array of youth, beauty, and loveliness. Then, bowing his head in prayer, and looking onward to the eternal years, he seemed to see them members of a heavenly choir, clothed in white, and singing, “Alleluia! salvation and glory and honor and power unto the Lord our God!”

After prayer, he read a hymn:—

“Now shall my head be lifted high

Above my foes around:

And songs of joy and victory

Within thy temple sound.”

There was a smile of satisfaction on Mr. Quaver’s countenance while selecting the tune, as if he had already won a victory. There was a clearing of throats; then Mr. Fiddleman gave the key on the bass-viol. As Mr. Quaver had told Paul that the school might sing when they pleased, or hold their tongues, he determined to act independently of Mr. Quaver.

“After one measure,” whispered Paul. He knew they would watch his hand, and commence in exact time. The old choir was accustomed to sing without regard to time.

Mr. Quaver commenced louder than usual,—twisting, turning, drawling, and flattening the first word as if it was spelled n-e-a-w. Miss Gamut and Mr. Cleff and the others dropped in one by one. Not a sound as yet from the school. All stood eagerly watching Paul. He cast a quick glance right and left. His hand moved,—down—left—right—up. They burst into the tune as if it was one voice instead of fifty. It was like the broadside of a fifty-gun frigate. The old choir was confounded. Miss Gamut stopped short. Captain Binnacle, who once was skipper of a schooner on the Lakes, and who owned a pew in front of the pulpit, said afterwards, that she was thrown on her beam-ends as if struck by a nor’wester and all her main-sail blown into ribbons in a jiffey. Mr. Quaver, though confused for a moment, recovered; Miss Gamut also righted herself. Though confounded, they were not yet defeated. Mr. Quaver stamped upon the floor, which brought Mr. Cleff to his senses. He looked as if he would say, “Put down the upstarts!” Mr. Fiddleman played with all his might; Miss Gamut screamed at the top of her voice, while Mr. Cleff puffed out his fat cheeks and became red in the face.

The people looked and listened in amazement. Mr. Surplice stood reverently in his place. Those who sat nearest the pulpit said that there was a smile on his countenance.

It was a strange fugue, but each held on to the end of the verse, the young folks getting out ahead of Mr. Quaver and his flock, and having a breathing spell before commencing the second stanza. So they went through the hymn. Then Mr. Surplice read from the Bible: “Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity! As the dew of Hermon, and as the dew that descended upon the mountains of Zion; for there the Lord commanded his blessing forevermore.”

Turning to the choir, he said, “My dear friends, I perceive that there is a want of unity in your services, as singers of the sanctuary; therefore, that the peace and harmony of the place may not be broken, I propose that, when the next psalm is given, the old members of the choir sing the first stanza, and the new members the second, and so through the hymn. By thus doing there will be no disagreement.”

Each one—old and young—resolved to do his best, for comparisons would be made. It would be the struggle for victory.

“I will give them a tune which will break them down,” Mr. Quaver whispered to Miss Gamut, as he selected one with a tenor and treble duet, which he and Miss Gamut had sung together a great many times. Louder and stronger sang Mr. Quaver. Miss Gamut cleared her throat, with the determination to sing as she never sang before, and to show the people what a great difference there was between her voice and Azalia Adams’s. But the excitement of the moment set her heart in a flutter when she came to the duet, which ran up out of the scale. She aimed at high G, but instead of striking it in a round full tone, as she intended and expected, she only made a faint squeak on F, which sounded so funny that the people down stairs smiled in spite of their efforts to keep sober. Her breath was gone. She sank upon her seat, covered her face with her hands, mortified and ashamed. Poor Miss Gamut! But there was a sweet girl behind her who pitied her very much, and who felt like crying, so quick was her sympathy for all in trouble and sorrow.

Paul pitied her; but Mr. Quaver was provoked. Never was his nose so red and fiery. Determined not to be broken down, he carried the verse through, ending with a roar, as if to say, “I am not defeated.”

The young folks now had their turn. There was a measure of time, the exact movement, the clear chord, swelling into full chorus, then becoming fainter, till it seemed like the murmuring of voices far away. How charming the duet! Where Mr. Quaver blared like a trumpet, Paul sang in clear, melodious notes; and where Miss Gamut broke down, Azalia glided so smoothly and sweetly that every heart was thrilled. Then, when all joined in the closing strain, the music rolled in majesty along the roof, encircled the pulpit, went down the winding stairs, swept along the aisles, entered the pews, and delighted the congregation. Miss Gamut still continued to sit with her hands over her face. Mr. Quaver nudged her to try another verse, but she shook her head. Paul waited for Mr. Quaver, who was very red in the face, and who felt that it was of no use to try again without Miss Gamut. He waved his hand to Paul as a signal to go on. The victory was won. Through the sermon Mr. Quaver thought the matter over. He felt very uncomfortable, but at noon he shook hands with Paul, and said, “I resign my place to you. I have been chorister for thirty years, and have had my day.” He made the best of his defeat, and in the afternoon, with all the old singers, sat down stairs.

Judge Adams bowed to Paul very cordially at the close of the service. Colonel Dare shook hands with him, and Rev. Mr. Surplice, with a pleasant smile, said, “May the Lord be with you.” It was spoken so kindly and heartily, and was so like a benediction, that the tears came to Paul’s eyes; for he felt that he was unworthy of such kindness.

There was one person in the congregation who looked savagely at him,—Miss Dobb. “It is a shame,” she said, when the people came out of church, speaking loud enough to be heard by all, “that such a young upstart and hypocrite should be allowed to worm himself into Mr. Quaver’s seat.” She hated Paul, and determined to put him down if possible.

Paul went home from church pleased that the school had done so well, and grateful for all the kind words he heard; but as he retired for the night, and thought over what had taken place,—when he realized that he was the leader of the choir, and that singing was a part of divine worship,—when he considered that he had fifty young folks to direct,—and that it would require a steady hand to keep them straight, he felt very sober. As these thoughts, one by one, came crowding upon him, he felt that he could not bear so great a responsibility. Then he reflected that life is made up of responsibilities, and that it was his duty to meet them manfully. If he cringed before, or shrank from them, and gave them the go-by, he would be a coward, and he never would accomplish anything. He would be nobody. No one would respect him, and he would not even have any respect for himself. “I won’t back out!” he said, resolving to do the best he could.

Very pleasant were the days. Spring had come with its sunshine and flowers. The birds were in their old haunts,—the larks in the meadows, the partridges in the woods, the quails in the fields. Paul was as happy as they, singing from morning till night the tunes he had learned; and when his day’s work was over, he was never too wearied to call upon Daphne with Azalia, and sing till the last glimmer of daylight faded from the west,—Azalia playing the piano, and their voices mingling in perfect harmony. How pleasant the still hours with Azalia beneath the old elms, which spread out their arms above them, as if to pronounce a benediction,—the moonlight smiling around them,—the dews perfuming the air with the sweet odors of roses and apple-blooms,—the cricket chirping his love-song to his mate,—the river forever flowing, and sweetly chanting its endless melody!

Sometimes they lingered by the way, and laughed to hear the grand chorus of bull-frogs croaking among the rushes of the river, and the echoes of their own voices dying away in the distant forest. And then, standing in the gravelled walk before the door of Azalia’s home, where the flowers bloomed around them, they looked up to the stars, shining so far away, and talked of choirs of angels, and of those who had gone from earth to heaven, and were singing the song of the Redeemed. How bright the days! how blissful the nights!

Carleton.

A neighbor, blessed with an extensive litter of Newfoundland pups, commenced one chapter in our family history by giving us a puppy, brisk, funny, and lively enough, who was received in our house with acclamations of joy, and christened “Rover.” An auspicious name we all thought, for his four or five human playfellows were all rovers,—rovers in the woods, rovers by the banks of a neighboring patch of water, where they dashed and splashed, made rafts, inaugurated boats, and lived among the cat-tails and sweet flags as familiarly as so many muskrats. Rovers also they were, every few days, down to the shores of the great sea, where they caught fish, rowed boats, dug clams,—both girls and boys,—and one sex quite as handily as the other. Rover came into such a lively circle quite as one of them, and from the very first seemed to regard himself as part and parcel of all that was going on, in doors or out. But his exuberant spirits at times brought him into sad scrapes. His vivacity was such as to amount to decided insanity,—and mamma and Miss Anna and papa had many grave looks over his capers. Once he actually tore off the leg of a new pair of trousers that Johnny had just donned, and came racing home with it in his mouth, with its bare-legged little owner behind, screaming threats and maledictions on the robber. What a commotion! The new trousers had just been painfully finished, in those days when sewing was sewing, and not a mere jig on a sewing-machine; but Rover, so far from being abashed or ashamed, displayed an impish glee in his performance, bounding and leaping hither and thither with his trophy in his mouth, now growling, and mangling it, and shaking it at us in elfish triumph as we chased him hither and thither,—over the wood-pile, into the wood-house, through the barn, out of the stable door,—vowing all sorts of dreadful punishments when we caught him. But we might well say that, for the little wretch would never be caught; after one of his tricks, he always managed to keep himself out of arm’s length till the thing was a little blown over, when in he would come, airy as ever, and wagging his little pudgy puppy tail with an air of the most perfect assurance in the world.

There is no saying what youthful errors were pardoned to him. Once he ate a hole in the bed-quilt as his night’s employment, when one of the boys had surreptitiously got him into bed with them; he nibbled and variously maltreated sundry sheets; and once actually tore up and chewed off a corner of the bedroom carpet, to stay his stomach during the night season. What he did it for, no mortal knows; certainly it could not be because he was hungry, for there were five little pair of hands incessantly feeding him from morning till night. Beside which, he had a boundless appetite for shoes, which he mumbled, and shook, and tore, and ruined, greatly to the vexation of their rightful owners,—rushing in and carrying them from the bedsides in the night watches, racing off with them to any out-of-the-way corner that hit his fancy, and leaving them when he was tired of the fun. So there is no telling of the disgrace into which he brought his little masters and mistresses, and the tears and threats and scoldings which were all wasted on him, as he would stand quite at his ease, lolling out his red, saucy tongue, and never deigning to tell what he had done with his spoils.

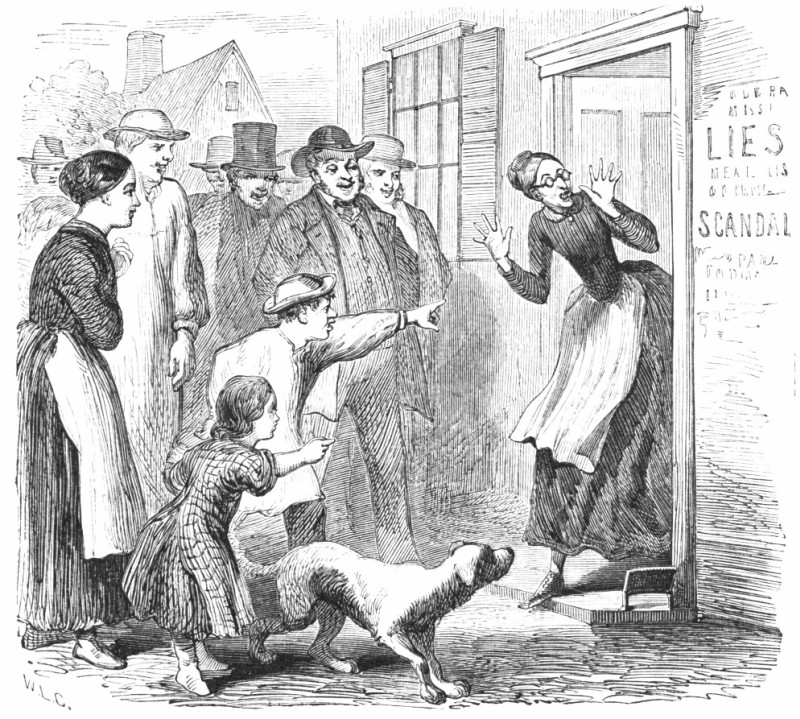

Notwithstanding all these sins, Rover grew up to doghood, the pride and pet of the family,—and in truth a very handsome dog he was.

It is quite evident from his looks that his Newfoundland blood had been mingled with that of some other races; for he never attained the full size of that race, and his points in some respects resembled those of a good setter. He was grizzled black and white, and spotted on the sides in little inky drops about the size of a three-cent piece; his hair was long and silky, his ears beautifully fringed, and his tail long and feathery. His eyes were bright, soft, and full of expression, and a jollier, livelier, more loving creature never wore dog-skin. To be sure, his hunting blood sometimes brought us and him into scrapes. A neighbor now and then would call with a bill for ducks, chickens, or young turkeys, which Rover had killed. The last time this occurred it was decided that something must be done; so Rover was shut up a whole day in a cold lumber-room, with the murdered duck tied round his neck. Poor fellow! how dejected and ashamed he looked, and how grateful he was when his little friends would steal in to sit with him, and “poor” him in his disgrace! The punishment so improved his principles that he let poultry alone from that time, except now and then, when he would snap up a young chick or turkey, in pure absence of mind, before he really knew what he was about. We had great dread lest he should take to killing sheep, of which there were many flocks in the neighborhood. A dog which once kills sheep is a doomed beast,—as much as a man who has committed murder; and if our Rover, through the hunting blood that was in him, should once mistake a sheep for a deer, and kill him, we should be obliged to give him up to justice,—all his good looks and good qualities could not save him.

What anxieties his training under this head cost us! When we were driving out along the clean sandy roads, among the piny groves of Maine, it was half our enjoyment to see Rover, with ears and tail wild and flying with excitement and enjoyment, bounding and barking, now on this side the carriage, now on that,—now darting through the woods straight as an arrow, in his leaps after birds or squirrels, and anon returning to trot obediently by the carriage, and, wagging his tail, to ask applause for his performances. But anon a flock of sheep appeared in a distant field, and away would go Rover in full bow-wow, plunging in among them, scattering them hither and thither in dire confusion. Then Johnny and Bill and all hands would spring from the carriage in full chase of the rogue; and all of us shouted vainly in the rear; and finally the rascal would be dragged back, panting and crestfallen, to be admonished, scolded, and cuffed with salutary discipline, heartily administered by his best friends for the sake of saving his life. “Rover, you naughty dog! Don’t you know you mustn’t chase the sheep? You’ll be killed, some of these days.” Admonitions of this kind, well shaken and thumped in, at last seemed to reform him thoroughly. He grew so conscientious, that, when a flock of sheep appeared on the side of the road, he would immediately go to the other side of the carriage, and turn away his head, rolling up his eyes meanwhile to us for praise at his extraordinary good conduct. “Good dog, Rove! nice dog! good fellow! he doesn’t touch the sheep,—no, he doesn’t.” Such were the rewards of virtue which sweetened his self-denial; hearing which, he would plume up his feathery tail, and loll out his tongue, with an air of virtuous assurance quite edifying to behold.

Another of Rover’s dangers was a habit he had of running races and cutting capers with the railroad engines as they passed near our dwelling.

We lived in plain sight of the track, and three or four times a day the old, puffing, smoky iron horse thundered by, dragging his trains of cars, and making the very ground shake under him. Rover never could resist the temptation to run and bark, and race with so lively an antagonist; and, to say the truth, John and Willy were somewhat of his mind,—so that, though they were directed to catch and hinder him, they entered so warmly into his own feelings that they never succeeded in breaking up the habit. Every day when the distant whistle was heard, away would go Rover, out of the door or through the window,—no matter which,—race down to meet the cars, couch down on the track in front of them, barking with all his might, as if it were only a fellow-dog, and when they came so near that escape seemed utterly impossible, he would lie flat down between the rails and suffer the whole train to pass over him, and then jump up and bark, full of glee, in the rear. Sometimes he varied this performance more dangerously by jumping out full tilt between two middle cars when the train had passed half-way over him. Everybody predicted, of course, that he would be killed or maimed, and the loss of a paw, or of his fine, saucy tail, was the least of the dreadful things which were prophesied about him. But Rover lived and throve in his imprudent courses notwithstanding.

The engineers and firemen, who began by throwing sticks of wood and bits of coal at him, at last were quite subdued by his successful impudence, and came to consider him as a regular institution of the railroad, and, if any family excursion took him off for a day, they would inquire with interest, “Where’s our dog?—what’s become of Rover?” As to the female part of our family, we had so often anticipated piteous scenes when poor Rover would be brought home with broken paws or without his pretty tail, that we quite used up our sensibilities, and concluded that some kind angel, such as is appointed to watch over little children’s pets, must take special care of our Rover.

Rover had very tender domestic affections. His attachment to his little playfellows was most intense; and one time, when all of them were taken off together on a week’s excursion, and Rover left alone at home, his low spirits were really pitiful. He refused entirely to eat for the first day, and finally could only be coaxed to take nourishment, with many strokings and caresses, by being fed out of Miss Anna’s own hand. What perfectly boisterous joy he showed when the children came back!—careering round and round, picking up chips and bits of sticks, and coming and offering them to one and another, in the fulness of his doggish heart, to show how much he wanted to give them something.

This mode of signifying his love by bringing something in his mouth was one of his most characteristic tricks. At one time he followed the carriage from Brunswick to Bath, and in the streets of the city somehow lost his way, so that he was gone all night. Many a little heart went to bed anxious and sorrowful for the loss of its shaggy playfellow that night, and Rover doubtless was remembered in many little prayers; what, therefore, was the joy of being awakened by a joyful barking under the window the next morning, when his little friends rushed in their night-gowns to behold Rover back again, fresh and frisky, bearing in his mouth a branch of a tree about six feet long, as his offering of joy.

When the family removed to Zion Hill, Rover went with them, the trusty and established family friend. Age had somewhat matured his early friskiness. Perhaps the grave neighborhood of a theological seminary and the responsibility of being a Professor’s dog might have something to do with it, but Rover gained an established character as a dog of respectable habits, and used to march to the post-office at the heels of his master twice a day, as regularly as any theological student.

Little Charley the second,—the youngest of the brood, who took the place of our lost little Prince Charley—was yet padding about in short robes, and seemed to regard Rover in the light of a discreet older brother, and Rover’s manners to him were of most protecting gentleness. Charley seemed to consider Rover in all things as such a model, that he overlooked the difference between a dog and a boy, and wearied himself with fruitless attempts to scratch his ear with his foot as Rover did, and one day was brought in dripping from a neighboring swamp, where he had been lying down in the water, because Rover did.

Once in a while a wild oat or two from Rover’s old sack would seem to entangle him. Sometimes, when we were driving out, he would, in his races after the carriage, make a flying leap into a farmer’s yard, and, if he lighted in a flock of chickens or turkeys, gobble one off-hand, and be off again and a mile ahead before the mother hen had recovered from her astonishment. Sometimes, too, he would have a race with the steam-engine just for old acquaintance’ sake. But these were comparatively transient follies; in general, no members of the grave institutions around him behaved with more dignity and decorum than Rover. He tried to listen to his master’s theological lectures, and to attend chapel on Sundays; but the prejudices of society were against him, and so he meekly submitted to be shut out, and wait outside the door on these occasions.

He formed a part of every domestic scene. At family prayers, stretched out beside his master, he looked up reflectively with his great soft eyes, and seemed to join in the serious feeling of the hour. When all were gay, when singing, or frolicking, or games were going on, Rover barked and frisked in higher glee than any. At night it was his joy to stretch his furry length by our bedside, where he slept with one ear on cock for any noise which it might be his business to watch and attend to. It was a comfort to hear the tinkle of his collar when he moved in the night, or to be wakened by his cold nose pushed against one’s hand if one slept late in the morning. And then he was always so glad when we woke; and when any member of the family circle was gone for a few days, Rover’s warm delight and welcome were not the least of the pleasures of return.

And what became of him? Alas! the fashion came up of poisoning dogs, and this poor, good, fond, faithful creature was enticed into swallowing poisoned meat. One day he came in suddenly, ill and frightened, and ran to the friends who always had protected him,—but in vain. In a few moments he was in convulsions, and all the tears and sobs of his playfellows could not help him; he closed his bright, loving eyes, and died in their arms.

If those who throw poison to dogs could only see the real grief it brings into a family to lose the friend and playfellow who has grown up with the children, and shared their plays, and been for years in every family scene,—if they could know how sorrowful it is to see the poor dumb friend suffer agonies which they cannot relieve,—if they could see all this, we have faith to believe they never would do so more.

Our poor Rover was buried with decent care near the house, and a mound of petunias over him kept his memory ever bright; but it will be long before his friends will get another as true.

Harriet Beecher Stowe.

As might be expected, the party thus invited to dinner had anything but a hospitable time of it. In a general way, the boys received pretty fair treatment from Mrs. Spangler; but on that particular occasion they saw that they were called in merely to be fed, and, the feeding over, that it would be most agreeable to her if they would thereupon clear out. Things had gone wrong with her on that unfortunate day, and they must bear the brunt of it. The good man of the house was absent at the neighboring tavern, it being one of his rainy days; hence the wife had all the remaining household at her mercy, and, being mostly an uncomplaining set, she could serve them with impunity just as the humor of the moment made it most convenient. The dinner was therefore nothing to speak of, and was quite unworthy of the great noise which the tin horn had made in calling them to it. There was a bit of boiled salt pork, almost too fat to eat, with potatoes and turnips, while the dessert consisted of pumpkin-sauce, which the dinner party might spread upon bread, if they thought proper.

Uncle Benny devoured his share of this rainy-day repast in silence, but inwardly concluded that it was next of kin to the meanest dinner he had ever eaten, for he was too well-bred to take open exception to it. As boys, especially farmers’ boys, are not epicures, and are generally born with appetites so hearty that nothing comes amiss, Joe and Tony managed to find enough, and were by no means critical,—quality was not so important a matter as quantity. It is true there was a sort of subdued mutiny against the unseasoned pumpkin-sauce, which was a new article on Farmer Spangler’s table, that showed itself in a general hesitancy even to taste it, and in a good long smell or two before a mouthful was ventured on; which being observed by Mrs. Spangler, she did unbend sufficiently to say that she had intended to give them pumpkin-pies, but an accident to her lard had interrupted her plans, so she gave them the best she had, and promised the pies for next day.

As Uncle Benny and the boys all knew that they had been called in merely to eat, and not to lounge about the stove, and were therefore expected to depart as soon as they had dined, when the scanty meal was over, they stepped out on the way to their wonted rendezvous, the barn. The rain had ceased, and there were signs of a clearing up. But the wide space between house and barn was wet and muddy, while in several places there were great puddles of water, around which they had to pick their way. These low places had always been an annoyance to Uncle Benny, as every rain converted them into ponds, which stood sometimes for weeks before drying up. They were so directly in the path to almost everything, that one had to navigate a long way round to avoid them; yet, though an admitted nuisance, no one undertook to fill them up.

When the party got fairly in among these puddles, the old man stopped, and told the boys he would teach them something worth knowing. Bidding Joe bring him a spade and hoe, he led the boys to a small puddle which lay lower on the sloping ground than any other, and in a few minutes opened a trench or gutter leading from it toward an adjoining lowland. The water immediately flowed away from the puddle through the gutter, until it fell to the level of the latter. He then deepened the gutter, and more water was discharged, and repeated the operation until the puddle was quite empty.

He then directed Joe to open a gutter between the puddle thus emptied and a larger one close by, then to connect a third with the second, until, by means of hoe and spade, he had the whole series of puddles communicating with each other, those on the higher ground of course discharging their contents into that first emptied, as it lay lower than the others. When the work was completed there was a lively rush of water down, through the gutter first cut, into the meadow.

“Now, boys,” said Uncle Benny, “this is what is called drainage,—surface drainage,—the making of water move off from a spot where it is a nuisance, thus converting a wet place into a dry one. You see how useful it is on this little piece of ground, because in a few days the bottom of these ponds will become so dry that you can walk over them, instead of having to go round them; and if Mr. Spangler would only have them filled up, and make the whole surface level, the water would run off of itself, and all these gutters could be filled up, leaving the yard dry and firm. These gutters are called open or surface drains, because they are open at the top; but when you make a channel deep enough to put in a wooden trunk, or brush, or stones, or a line of tiles, for the water to flow through, and then cover up the whole so that one can walk or drive over it, it is called an under-drain, because it is under the surface of the ground.”

“But does draining do any good?” inquired Joe.

“Why,” replied Uncle Benny, “it is impossible to farm profitably without drainage of some kind; and the more thoroughly the land is drained of its superfluous water, the surer and better will be the crops. I suppose that not one of you likes to have wet feet. Well, it is the same thing with the roots and grains and grasses that farmers cultivate,—they don’t like wet feet. You know the corn didn’t grow at all in that low place in our cornfield this season; that was because the water stood there from one rain to another,—the corn had too much of it. You also saw how few and small were the potatoes in that part of the patch that runs close down to the swamp. Water is indispensable to the growth of plants, but none will bear an excessive supply, except those that grow in swamps and low places only. Many of these even can be killed by keeping the swamp flooded for a few weeks; though they can bear a great deal, yet it is possible to give even them too much. Our farms, even on the uplands, abound in low places, which catch and hold too much of the heavy rains for the health of the plants we cultivate. The surplus must be got rid of, and there is no other way to do that than by ditching and draining. Under-draining is always best. Let a plant have as much water as it needs, and it will grow to profit; but give it too much, and it will grow up weak and spindling. You saw that in our cornfield. There are some plants, as I said before, that grow only in wet places; but you must know that such are seldom useful to us as food either for man or beast. Nobody goes harvesting after spatterdocks or cattail. This farm is full of low, wet places, which could be drained for a very little money, and the profits from one or two crops from the reclaimed land would pay back the whole expenses. Indeed, there is hardly one farm in a thousand that would not be greatly benefited by being thoroughly under-drained. But as these puddles are nearly empty, come over to the barn-yard,—they will be dry enough to-morrow.”

Uncle Benny led the way into a great enclosure that was quite full of manure. It lay on a piece of sloping ground adjoining the public road, in full view of every person who might happen to drive by. It was not an agreeable sight to look at, even on a bright summer day; and just now, when a heavy rain had fallen, it was particularly unpleasant. In addition to the rain, it had received a copious supply of water from the roofs of all the barns and sheds that surrounded it. Not one of them was furnished with a gutter to catch and carry off the water to some place outside the barn-yard, but all that fell upon them ran off into the manure. Of course the whole mass was saturated with water. Indeed, it was not much better than a great pond, a sort of floating bog, yet not great enough to retain the volume of water thus conducted into it from the overhanging roofs. There was not a dry spot for the cows to stand upon, and the place had been in this disagreeable condition so long, that both boys and men went into it as seldom as possible. If the cows and pigs had had the same liberty of choice, it is probable they too would have given it as wide a berth.

The old man took them to a spot just outside the fence, where a deep gutter leading from the barn-yard into the public road was pouring forth into the latter a large stream of black liquor. As he pointed down the road, the boys could not see the termination of this black fluid, it reached so far from where they stood. It had been thus flowing, night and day, as long as the water collected in the barn-yard. The boys had never noticed any but the disagreeable part of the thing, as no one had taken pains to point out to them its economic or wasteful features.

“Now, boys,” said Uncle Benny, “there are two kinds of drainage. The first kind, which I have just explained to you, will go far toward making a farmer rich; but this kind, which drains a barn-yard into the public road, will send him to the poor-house. Here is manure wasted as fast as it is made,—thrown away to get rid of it,—and no land is worth farming without plenty of manure.”

“But the manure stays in the barn-yard,” replied Tony. “It is only the water that runs off.”

“Did you ever suck an orange after somebody had squeezed out all the juice?” asked Uncle Benny. “If you did, you must have discovered that he had extracted all that there was in it of any value,—you had a dry pull, Tony. It is exactly so with this barn-yard. Liken it to an orange, though I must admit there is a wide difference in the flavor of the two. Here Mr. Spangler is extracting the juice, throwing it away, and keeping the dry shell and insides for himself. Farmers make manure for the purpose of feeding their plants,—that is, to make them grow. Now, plants don’t feed on those piles of straw and cornstalks, that you say remain in the yard, but on the liquor that you see running away from them. That liquor is manure,—it is the very life of the manure heap,—the only shape that the heap can take to make a plant grow. It must ferment and decay, and turn to powder, before it can give out its full strength, and will not do so even then, unless water comes down upon it to extract just such juices as you now see running to waste. The rain carries those juices all through the ground where the plant is growing, and its thousands of little rootlets suck up, not the powdered manure, but the liquor saturated with its juices, just as you would suck an orange. They are not able to drink up solid lumps of manure, but only the fluid extracts. Boys, such waste as this will be death to any farm, and your father must make an entire change in this barn-yard. Don’t you see how it slopes toward the road, no doubt on purpose to let this liquid manure run off? He must remove it to a piece of level ground, and make the centre of it lower than the sides, so as to save every drop. If he could line the bottom with clay, to prevent loss by soaking into the ground, so much the better. If he can’t change it, then he should raise a bank here where we stand, and keep the liquor in. Then every roof must have a gutter to catch the rain, and a conductor to carry it clear of the yard. The manure would be worth twice as much if he would pile it up under some kind of cover. Then, too, the yard has been scraped into deep holes, which keep it constantly so wet and miry that no one likes to go into it, and these must be filled up.”

“But wouldn’t that be a great deal of work?” inquired Tony.

“Now, Tony,” replied the old man, “don’t expect to get along in this world without work. If you work to advantage, as you would in doing such a job as this, the more you do the better. You have set up to be a farmer, and you should try to be a good one, as I consider a poor farmer no better than a walking scarecrow. No man can be a good one without having things just as I tell you all these about this barn-yard ought to be. Whatever you do, do well. I know it requires more work, but it is the kind of work that pays a profit, and profit is what most men are aiming at. If this were my farm, I would make things look very different, no matter how much work it cost me. I can always judge of a man’s crops by his barn-yard.”

“Then I’m afraid this is a poor place to learn farming,” said Joe. “Father don’t know near as much about doing things right as you do, and he never talks to us, and shows us about the farm like you.”

“He may know as much as I do, Joe,” replied Uncle Benny, “but if he does, he don’t put it into practice;—that is the difference between us.”

“I begin to think it’s a poor place for me, too,” added Tony. “I have no friends to teach me, or to help me.”

“To help you?” exclaimed the old man, with an emphasis that was quite unusual to him; “you must help yourself. You have the same set of faculties as those that have made great men out of boys as humbly born as you, and you will rise or sink in proportion to the energy you exert. We can all succeed if we choose,—there is no fence against fortune.”

“What does that mean?” demanded Tony.

“It means that fortune is as an open common, with no hedge, or fence, or obstruction to get over in our efforts to reach it, except such as may be set up by our own idleness, or laziness, or want of courage in striving to overcome the disadvantages of our particular position.”

While this conversation was going on, the boys had noticed some traveller winding his slow and muddy way up the road toward where they were standing. As he came nearer, they discovered him to be a small boy, not so large as either Joe or Tony; and just as Uncle Benny had finished his elucidation of the fence against fortune, the traveller reached the spot where the group were conversing, and with instinctive good sense stepped up out of the mud upon the pile of rails which had served as standing-ground for the others. He was a short, thick-set fellow, warmly clad, of quick movement, keen, intelligent look, and a piercing black eye, having in it all the business fire of a juvenile Shylock. Bidding good afternoon to the group, and scraping from his thick boots as much of the mud as he could, he proceeded to business without further loss of time. Lifting the cover from a basket on his arm, he displayed its flashing contents before the eyes of Joe and Tony, asking them if they didn’t want a knife, a comb, a tooth-brush, a burning-glass, a cake of pomatum, or something else of an almost endless list of articles, which he ran over with a volubility exceeding anything they had ever experienced.

The little fellow was a pedler. He plied his vocation with a glibness and pertinacity that confounded the two modest farmer’s boys he was addressing. Long intercourse with the great public had given him a perfect self-possession, from which the boys fairly shrunk back with girlish timidity. There was nothing impudent or obtrusive in his manner, but a quiet, persevering self-reliance that could not fail to command attention from any audience, and which, to the rustics he was addressing, was particularly imposing. To Uncle Benny the scene was quite a study. He looked and listened in silence. He was struck with the cool, independent manner of the young pedler, his excessive volubility, and the tact with which he held up to Joe and Tony the particular articles most likely to attract their attention. He seemed to know intuitively what each boy coveted the most. Tony’s great longing had been for a pocket-knife, and Joe’s for a jack-knife. The boy very soon discovered this, and, having both in his basket, crowded the articles on his customers with an urgency that nothing but the low condition of their funds could resist. After declining a dozen times to purchase, Tony was forced to exclaim, “But we have no money. I never had a shilling in my life.”

The pedler-boy seemed struck with conviction of the truth of Tony’s declaration, and that he was only wasting time in endeavoring to sell where there was no money to pay with. He accordingly replaced the articles in his basket, shut down the lid, and with unaltered civility was bidding the company good bye, when Uncle Benny broke silence for the first time.

“What is your name, my lad?” he inquired.

“John Hancock, sir,” was the reply.

“I have heard that name before,” rejoined Uncle Benny. “You were not at the signing of the Declaration of Independence?”

“No, sir,” replied the courageous little fellow, “I wish I had been,—but my name was there.”

This was succeeded by quite a colloquy between them, ending with Uncle Benny’s purchasing, at a dollar apiece, the coveted knives, and presenting them to the delighted boys. Then, again addressing the pedler, he inquired, “Why do you follow this business of peddling?”

“Because I make money by it,” he quickly replied.

“But have you no friends to help you, and give you employment at home?” continued the old man.

“Got no friends, sir,” he responded. “Father and mother both dead, and I had to help myself; so I turned newsboy in the city, and then made money enough to set up in peddling, and now I am making more.”

Uncle Benny was convinced that he was talking with a future millionnaire. But while admiring the boy’s bravery, his heart overflowed with pity for his loneliness and destitution, and with a yearning anxiety for his welfare. Laying his hand on his shoulder, he said: “God bless you and preserve you, my boy! Be industrious as you have been, be sober, honest, and truthful. Fear God above all things, keep his commandments, and, though you have no earthly parent, he will be to you a heavenly one.”

The friendless little fellow looked up into the old man’s benevolent face with an expression of surprise and sadness,—surprise at the winning kindness of his manner, as if he had seldom met with it from others, and sadness, as if the soft voices of parental love had been recalled to his yet living memory. Then, thanking him with great warmth, he bid the company good bye, and, with his basket under his arm, continued his tiresome journey over the muddy highway to the next farm-house.

“There!” said the old man, addressing Tony, “did you hear what he said? ‘Father and mother both dead, and I had to help myself!’ Why, it is yourself over again. Take a lesson from the story of that boy, Tony!”

Author of “Ten Acres Enough.”

The house to which the aged negress bore the wounded boy was a square, antiquated mansion, originally something in the fashion of the old farm-houses of New England. The hand of improvement, however, had been busy with it, until it had assumed the appearance of a country clown, who, above his own coarse brogans and homespun trousers, is wearing the stove-pipe hat, fancy waistcoat, and “long-tail blue” of some city gentleman. For a house, it had the oddest-looking face you ever saw. Its nose was a porch as ugly and prominent as the beak of President Tyler; and its eyes were wide, sleepy windows, which seemed to leer at you in a half-comic, half-wicked way. One of its ears was a round protuberance, something like the pole “sugar-loaves” the Indians live in; the other, a square box resembling the sentry-houses in which watchmen hive of stormy nights. Just above its nose, a narrow strip of weather-boarding answered for a forehead; and right over this, a huge pigeon-coop rose up in the air like the top-knot worn in pictures by that “old public functionary,” Mr. Buchanan. The rim of its hat was a huge beam, apparently the keel of some ship gone to roost, and its crown was a cupola, half carried away by a cannon-shot, and looking for all the world like a dilapidated beaver, which had been pelted by the storms of a dozen hard winters. The whole of its roof, in fact, looked like the hull of a vessel stove in amidships, and turned bottom upwards; and, with its truncated gables, reminded one of those down-east craft, which an old sea-captain used to tell me, when I was a boy, were built by the mile, and sawed off at the ends so as to suit any market.

But, notwithstanding these odd features, the old house had a most cosey and comfortable air about it. Before its door great trees were growing, and Virginia creepers and honeysuckles were clambering over its brown walls and wide windows, filling the yard with fragrance, and hiding with their blooming beauty at least one half of its grotesque ugliness.

Pausing to rest awhile on its door-step, old Katy entered its broad hall, and bore James into the “sugar-loaf” projection of which I have spoken. It was a little alcove built off from the library, and furnished with a few chairs, a wash-stand, and a low bed covered with a patch-work counterpane. On this bed the old woman laid the wounded boy; and then, sinking into a chair, and wiping the perspiration from her face, she said to him, “You’s little, honey, but you’s heaby,—right heaby fur sich a ole ’ooman ter tote as I is.”

“I know I am, Aunty,” said the little boy, to whom the long walk had brought great pain, and who now began to feel deathly sick and faint. “You might as well have let me die there.”

“Die, honey!” cried the old negress, springing to her feet as nimbly as if she had been a young girl; “you hain’t a gwine ter die,—ole Katy woan’t leff you do dat, nohow.”

James looked at her with a weary, but grateful look, while, undoing his jacket and waistcoat, she wet his shirt with a dampened cloth, and tried to remove it from his wound. The long walk—old Katy’s gait was a swaying movement, nearly as rough as a horse’s trot—had set the wound to bleeding again, so the shirt came away without any trouble, and then she saw the deep, wide gash in the little boy’s side. The bayonet had entered his body at the outer edge of the ribs, just above the hip, and, going clear through, had come out at his back, making a ghastly wound. It seemed all but impossible to keep the precious life from oozing away through such a frightful rent; but, covering it hastily with the cloth, the old woman said to James in a cheerful way: “Taint nuffin’, honey,—nuffin’ ter hurt. Ole Katy’s seed a heap ob wuss ones nur dat; and dey’s gwine ’bout, as well as eber dey was. You’ll be ober it right soon. But you muss keep quiet, honey, and not grebe nor worry after you mudder, nur nuffin’; fur ef you does, de feber mought git in dar, and ef dat ar fire onct got tur burnin’ right smart, dar’s no tellin’ but it might burn you right up, spite ob all de water in de worle.”

The pain of his wound did not prevent the little fellow from smiling at the idea of his being put out like a house on fire; but he made no reply, and the old negress, gently drawing off his pantaloons and shoes, said again, in a cheerful tone: “Now, honey, you muss keep bery quiet, while Aunty gwoes fur de ice. We’se plenty ob dat ’bout de house. She’ll bind it on ter de hurt, till it’m so cold you’ll tink you ’m layin’ out on de frosty ground right in the middle ob winter.”

She went away, but soon returned with the ice. Binding it about his wound, she brushed the long hair from the little boy’s face; and then, bending down, kissed his forehead.

“You won’t mind a pore ole brack ’ooman doin’ dat, honey. She can’t holp it; case you looks jest like her own little Robby, dat’s loss and gone,—loss and gone. Only he ’m a little more tanned nur you am,—a little more tanned,—dat’s all.”

“And you had a little boy!” said James, opening his eyes, and looking up pleasantly at the old woman; “I hope he isn’t dead.”

“No, he haint dead, honey,—not dead; but he ’m loss and gone now,—loss and gone from ole Katy—foreber. Oh! oh!” and the poor woman swayed her body back and forth on her chair, and moaned piteously.

“I’m sorry,—very sorry, Aunty,” said James, raising his hand to brush away his tears. “One so good as you ought not to have any trouble.”

“But I haint good, honey; and you mussn’t be sorry,—you mussn’t be nuffin’, only quiet, and gwo ter sleep. Ole Katy woan’t talk no more.” In a moment, however, she added: “Hab you a mudder, honey?”

“Yes, Aunty, and I’m all she has in the world.”

“And hab she eber teached you ter pray?”

“Yes. I pray every morning and night. You came to me because I prayed.”

“I done dat, honey! De good Lord send me case you ax him, you may be shore. And, maybe, ef we ax him now, he’ll make you well. I knows young massa say taint no use ter pray,—dat de Lord neber change, and do all his business arter fix’ laws; but I reckon one o’ dem laws am dat we muss pray. I s’pose it clars away de tick clouds dat am ’tween us and de angels, so dey kin see whar we am, and what we wants, and come close down and holp us. And, honey, we’ll pray now, and maybe de good Lord will send de angels, and make you well.”

Kneeling on the floor by the side of the bed, she then prayed to Him who is her Father and our Father,—her God and our God. It was a low, simple, humble prayer, but it reached the ear of Heaven, and brought the angels down.

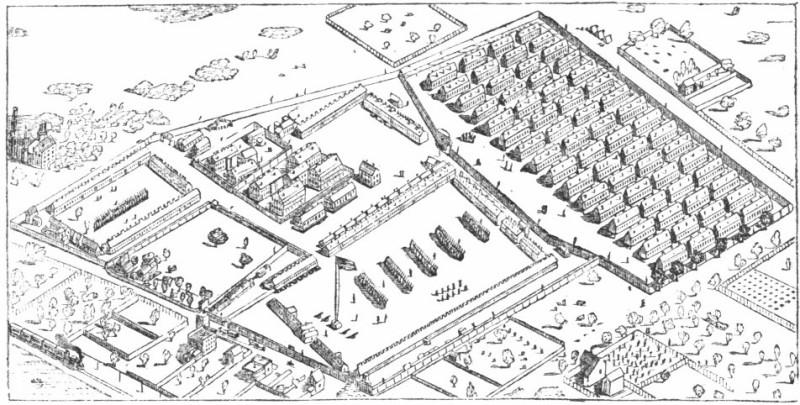

It was eight days before James could sit up, and day and night, during all of that time, Old Katy watched by him. Every few hours she changed the bandage, and bound fresh ice upon his wound; and that was all she did,—but it saved his life. The only danger was from inflammation,—the ice and a low diet kept that down, and his young and vigorous constitution did the rest. At the end of a fortnight, leaning on the arm of the old negress, he walked out into the garden and sat down in a little arbor, in full view of the recent battle-ground. It was a clear, mild morning in May, but a dark cloud overhung the little hill, as though the smoke of the great conflict had not yet cleared away, but, with all its tale of blood and horror, was still going up to heaven. And what a tale it was! Brothers butchered by brothers, fathers slaughtered by sons, and all to further the bad ambition of a few wicked men,—so few that one might count them on the fingers of his two hands!

“And what became of the wounded after the battle, Aunty?” asked the little boy, as the sight of the grassy field, trodden down by many feet, and still reddened, here and there, with the blood of the slain, brought the awful scene all freshly to his mind. “You haven’t told me that.” (She had forbidden him to talk, for she knew that his recovery depended almost entirely on his being kept free from excitement.)

“The dead ones war buried, and the wounded war toted off by de gray-backs, honey, de evenin’ and mornin’ arter I brung you away from dar. De Secesh had de field, ye sees, at lass; and dey tuck all de Nordern folks as was leff, pris’ners.”

“And what became of the poor soldier who wanted water for his son? Do you know, Aunty?”

“When I wus a gwine on de hill, arter you go asleep in de house, I seed dat pore man a wrappin’ up de little boy, and totin’ him off ter de woods. I ax him whar he wus gwine, and he look at me wid a strange, wild look, and say nuffin’, only, ‘Home—home.’ He look so bery wild, and so fierce loike, dat I reckon he wus crazed,—clean gone. De lass I seed o’ him, he wus gwine stret ter you kentry,—right up Norf,—wid de little chile in him arms.”

“Poor man!” cried the boy. “How many have fared worse than I have!”

“A heap, honey. I knows a heap o’ big folks wuss off nur ole Katy.”

“And you say that, Aunty,—you, who are a slave, and have lost your——” He checked himself, for he saw a look of pain passing across the face of the old negress. It was gone in a moment, and then, in a low, chanting tone,—broken and wild at times, but touching and sad, as the strange music of the far-off land she came from,—she told him something of what her life had been.

Her little Robby,—her last one,—she said, had been taken away to the hot fields, where the serpents sting, and the fevers breed, and the black man goes to die. All were gone,—all her children,—stolen, sold away, before they knew the Lord, or the good from the evil. Sold! because her master owed gambling debts, and her mistress loved the diamond things that adorn the hair and deck the fingers! But one she begged,—the mother of the boy,—and she grew up pure as the snow before it leaves the cloud. Pure as the snow, but “young massa” came, and the snow fell—down—down to the ground—soiled like the snow we tread on. She tired him then; and he sold her to be a trader’s thing. But the boy was left,—“young massa’s” child,—the boy he promised her forever. She brought him up, taught him to read, and set the whole world by him. Then the troubles came,—the dark hour before the morning. She felt them in the air, and knew why all the storm was brewing. It broke her heart, but she sent him away to the Union lines, to grow up there a freeman. The Northern general drove him back, and then—“young massa” sold him to work and starve and faint and die among the swamps of Georgia. And now—they all were gone! All were lost,—but the Lord was left. He had heard her cry,—was coming now, with vengeance in his great right hand, to lift the lowly from the earth, and bring the mighty down.

Her last words were spoken with an energy that startled James. In his cold Northern home he had learned little of the warm Southern race, in whose veins a fire is slumbering that, if justice be not done them, will yet again set this nation ablaze.

The plantation, and old Katy too, belonged to Major Lucy, a great man in that part of Virginia, who, at its outbreak, had joined the wicked Rebellion which is bringing so much misery on our country. He was away with Lee’s army when Grant crossed the Rapidan, but he no sooner heard of that event than he repaired to his home, and removed his slaves and more valuable property to the far South. Old Katy he left behind, partly because she refused to go, and partly because he thought she might somewhat protect his house from the Northern soldiers, who, he supposed, would soon be in that region. For this reason the old negress was alone in the great mansion, and to this fact James owed his preservation; for, though her white owners might have given him hospitable care, they would not have afforded him the devoted attention which she had, and that it was which saved his life.

While he was so very sick she had slept in his little room, but now that he was out of all danger, and rapidly recovering, she made her bed in the large library leading from it, leaving, however, the door ajar at night, so she could at once hear the lightest sound. Every evening she took the great Bible from a shelf in this library, and read to him, generally from the Psalms, or Isaiah,—that poem grander than the Iliad, or any which poet yet has written. One night, about a fortnight after they were first together in the garden, she read the fifteenth and sixteenth chapters of that book, and then said to him: “Moab, honey, am dis Southern land, dat am ‘laid waste, and brought ter silence,’ case it hab ‘oppressed His people and turned away from His testimonies.’ But de Lord say yere dat widin’ three yars it shill be brought low, and its glory be contemned; and de remnant shill be bery small and feeble; but den dey shill take counsel, execute judgment, and let de outcasts dwell widin’ dem.”

“I hope it won’t be three years, Aunty,” said James. “That’s an awful long while to wait.”

“It ’pears long ter you, honey, but ole Katy hab waited a’most all har life,—eber sence she come ober in de slave-ship; and now all she ask ob de Lord am ter leff her see dat day. And she know he will! ’case he hab took har eberyting else,—eberyting,—eben har little Robby.”

“No! He hain’t, Granny! Robby’s yere, jest so good as new.”

Engaged as they had been in conversation, the old woman and the little boy had not observed a comely lad, a trifle taller than James, in a torn hat and tattered trousers, who a moment before had entered the room. As he spoke, old Katy sprang to her feet, let the Bible fall to the floor, and, with a wild cry, threw her arms about him.

Edmund Kirke.

Nearly the whole school were sitting on the grass on the shady side of the rock, waiting for the school-house door to be unlocked, when Martha Ballston came running up from Rene’s with her sun-bonnet in her hand, her hair all flying, and only just breath enough left to cry out, “O, I can tell you what,—teacher’s beau’s come!”

“Teacher’s beau’s come!” mimicked Martial Mayland. “Did you come rushing in here like a steam fire-engine just to tell that?”

“Now,” thrust in Nathan, “I expected at least that Richmond was taken, and peace come, and Jeff Davis drinking hemlock like anything!”

“But does she have a beau?” inquired Cicely, to whom a beau seemed a far more solemn and august thing than to the boys.

“Yes, she’s coming down the hill with a spick-span clean dress, and a bran-new cape, and her best bonnet on, and the most elegantest parasol ever you saw, with fringe all round it, and a bow on top!”

“O, I know,” said Olive; “Aunt Jane’s going to have company this afternoon, and teacher’s going.”

“No,” replied Martha. “She’s going to the panorama, ’n’ he’s going to carry her—in Mr. Court’s chaise.”

“Perhaps it’s her brother,” suggested Cicely, who could not quite familiarize herself with the momentous fact of a “beau.”

“No,” persisted Martha, “it’s her beau; for Trip was in there, and says she seen him give her a whole handful of peppermints, didn’t he, Trip?”

“Yes, he did,” said little Trip decidedly, which seemed to settle the question; for the little people of Applethorpe could not conceive that one could ever voluntarily surrender anything so valuable as peppermints to one less important than a “girl.” “Girl” is the feminine for “beau” in Applethorpe.

Now I dare say that Miss Stanley enjoyed her “beau’s” visit, and her drive with him, and her panorama, very much, but I wonder if she ever knew that, after all, her little pupils had the best of it. For school was dismissed at two o’clock, and what then? “Why, of course,” said Olive, who was always coming to the surface, “we must go and do something. We don’t want to act just as if it was recess, or school was out, like always.”

“There’s blackberries down in the pasture,” spoke up Gerty; “we might go a blackberrying.”

“Yes,” said Nathan, “I know, sixteen vines and three blackberries to fill a dozen dinner-pails.”

“O,” cried Martha, with a sudden leap, “I do know. On the knoll over towards the factory they are as thick as spatters. The ground’s black.”

“But you can’t get across the meadow,” said Garnet.

“Yes you can. You can go through Grandsir’s cow-yard, and through ten-acres, and go up the lane, and then get over the bars, and then you’re right on the knoll, and no meadow to get over.”

“I’d like to see us all going through Grandsir Beck’s cow-yard!” cried Nathan.

Now you must know—I am sorry to be obliged to say it, but it is true—that Grandsir Beck was a very cross and disagreeable old man. I suppose the trouble was, that he had been a cross and disagreeable young man, and as he grew older he grew worse. To excuse him, we will suppose he had had a great many troubles of which the children knew nothing; and some few troubles he had, such as naughty boys under his apple and cherry trees, which I am afraid some of the children did know something about. Still, that was no reason why he should flourish his cane and growl so gruffly at quiet, innocent little girls, who not only never thought of entering his orchard, but were almost afraid even to go by his house. At least, if I ever live to be an old man, and am as cross and disagreeable as Grandsir Beck, I give you full leave to dislike me as heartily as the Applethorpe children did him, and I will not blame you for it at all.

But Martha assured them that Grandsir Beck had gone to market that day, and didn’t get home till four o’clock, no, never! So, after some deliberation, and some hesitation on the part of the little girls, and with much tremor in their hearts, the whole troop started. The boys let down the cow-yard bars on one side, and the girls flew through with visions of the dreadful cane whirling in air, and the dreadful voice shouting threats behind them, though both were a dozen miles away at the market town. But they could not wait to take down the bars that led into “ten-acres”; they scrambled through, they crept under, they climbed over, and did not for one moment feel safe till they had passed “ten-acres,” and were in the lane, beyond sight of Grandsir Beck’s house. Then they took time to pant and laugh, and every one declare that he ran because the others did, but wasn’t scared himself the least bit. O no!

Martha had hardly belied the blackberries. Olive declared they were even thicker than spatters,—though how thick spatters are I never could exactly find out,—and “O how fat they are!” cried Cicely, “and seem to wink up at you under the leaves.”

“Why, I don’t see one,” cried Trip, picking her way daintily and disconsolately among the vines.

“Course you don’t,” answered Olive; “she just tiptoes round, expecting the blackberries to say, ‘Hullo!’ Why don’t you dig down under the leaves and find ’em?”

“Come up here under the wall, Trip,” called Nathan; “they’re always better where it’s dark.”

Trip clambered up, for Nathan and she were fine friends. In fact, Trip was generally fine friends with everybody, and never had any suspicion that people might not like her.

“What you stopping for, Trip?” called Nathan, as she halted midway.

“Why, I’ve teared a piece of skin most off my new shoe,—but I don’t care, I can stick it on. O Nathan! you’ve got your pail covered,” and she crouched down by his side admiringly and confidingly.

“And you,—how many have you!” She tilted her pail so that he could see one red, one green, and one withered on one side,—a sorry show.

“You’ve been eating! Let’s see your tongue!” But the little red tongue was innocent of stain.

“Never mind,” said he comfortingly; “you come here. There, hold back the vines so,—keep your foot on them. I’ll find another place, and don’t you say a word,—when my pail’s full, I’ll turn to and fill yours. You keep still.”

And so they plucked and chatted, the sunshine burning into their young blood, and the blackberries reddening them even more than the sun; busy tongues, busy fingers, aprons sadly torn and stained,—but what matter, since the tin-pails were every moment weighing down more heavily. Even little Trip, by vigorous electioneering, pitiful complaints of poverty, and broad hints concerning generosity, had coaxed handfuls enough out of other pails to half fill her own, and “She’s done beautifully,” declared Olive; “she hasn’t tumbled down and spilt ’em all more’n forty times!”

“O now, I haven’t tumbled forty—” began Trip in indignant protest; but, “Eh! Eh! U-g-h! you young rogues! I’ll set the dogs on ye! U-g-h! I’ll cane ye! U-g-h! Eh! I’ll have your hides off, and make whip-stocks of ’em! Eh!”

O fright and terror! It was Grandsir Beck, there, coming over the hill, not a dozen rods off, shaking his cane and roaring dire threats with that dreadful, gruff voice. Then you may be sure there was a scampering. Blackberries were forgotten, and the whole meadow seemed full of Grandsir Becks. Olive, who for want of a pail, had been filling her sun-bonnet, skipped it along by one string as if there had been nothing in it. Cicely, besides filling her pail, had gathered up her apron for further deposits, and kept brave hold of one corner, but in her fright did not notice that the other was loose, and that all the berries had rolled out. Trip’s older sister, Gerty, seized her by the hand, and of course dragged her to the ground the first minute. Trip, unable to use her feet and fancying herself already in the grip of Grandsir Beck, gave herself up to despair, stood stock-still, and expressed her feelings in one long, steady scream, without any ups or downs in it. The boys heard her, and rushed back. “Get along with you, Gerty, quick!” and Nathan and Martial took Trip by the hand and ran. The poor child, recovering courage, went through all the motions of running; but, in their strong clutch, her little toes hardly touched the ground. Over the knoll, through the wet meadow, across the brook, helter-skelter, they poured, reached the walls singly and in groups, clambered over pell-mell, and fled along the highway. Aleck was the last out, an overgrown, ill-taught boy, capable of doing well or ill, according to the company he was in. He came rolling leisurely along, out of breath, holding his sides, dragging his feet behind him, calling on the others to stop, and threw himself on the ground when he came up with them, laughing immoderately. His mirth reassured them. “O, it’s too good! too good!” he gasped.

“What is it? What is it? O, where is he?” cried a dozen voices.

“Going to Chiney, last I see of him.”

“Has he stopped? Is he coming?” moaned little Trip.

“Give a fellow time to breathe, can’t you! Stopped! I guess he is pretty thoroughly. Look-a-here. Don’t you know the ditch down there where the flags are? Well, I run that way and he after me, and I gave a flying leap, and over went I, and, don’t you think, he after me, and dumped right down into the ditch! Oh! oh!”

“But Aleck!” cried Cicely, “didn’t it hurt him?”

“No, soft as a feather-bed. But you see he can’t get out!”

“Why, you haven’t left him there? He isn’t there now!”

“No, he was sinkin’ fast. Got to Chiney by this time. You see he called to me to help him out, and I went back, and I asked him if he wouldn’t hit me if I’d help him out, and he promised no, and I tugged him, and yanked him, and got him half out, and I went to give him his cane, and, I tell you, he glared at me so, I let him drop and run. He’d a hit me over the head, sir, the next minute, promise or no promise.” And Aleck’s own eyes flashed with the remembrance.

“Boys,” said Nathan, after a pause, “we must go and get him out.”