* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: The Story of the Mikado

Date of first publication: 1921

Author: Sir W.S. (William Schwenck) Gilbert (1836-1911)

Date first posted: Nov. 15, 2016

Date last updated: Nov. 15, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20161115

This ebook was produced by: Iona Vaughan, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

THE STORY OF THE MIKADO

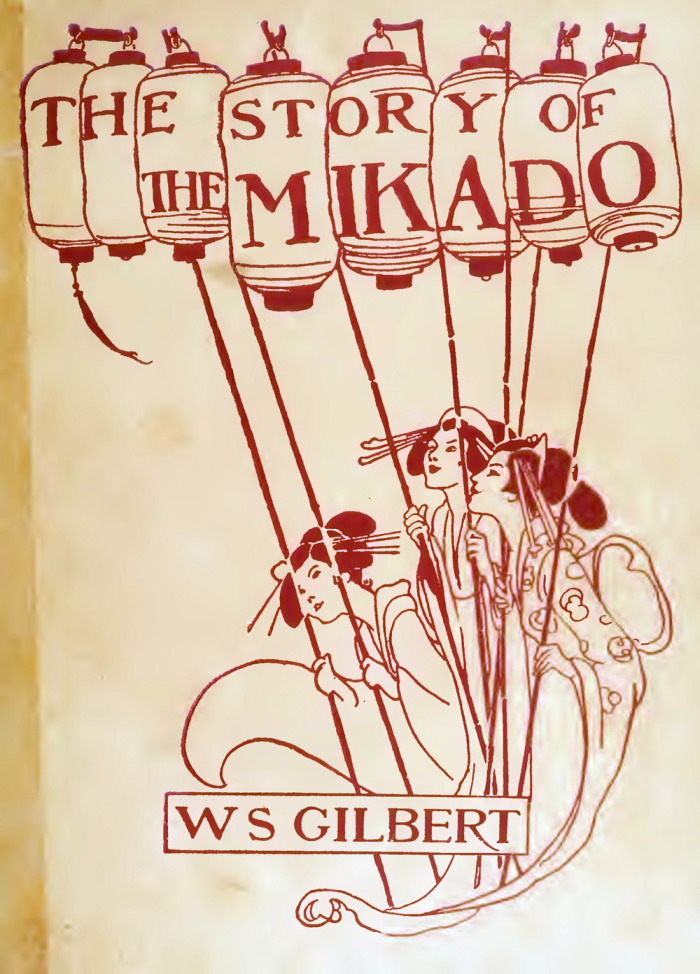

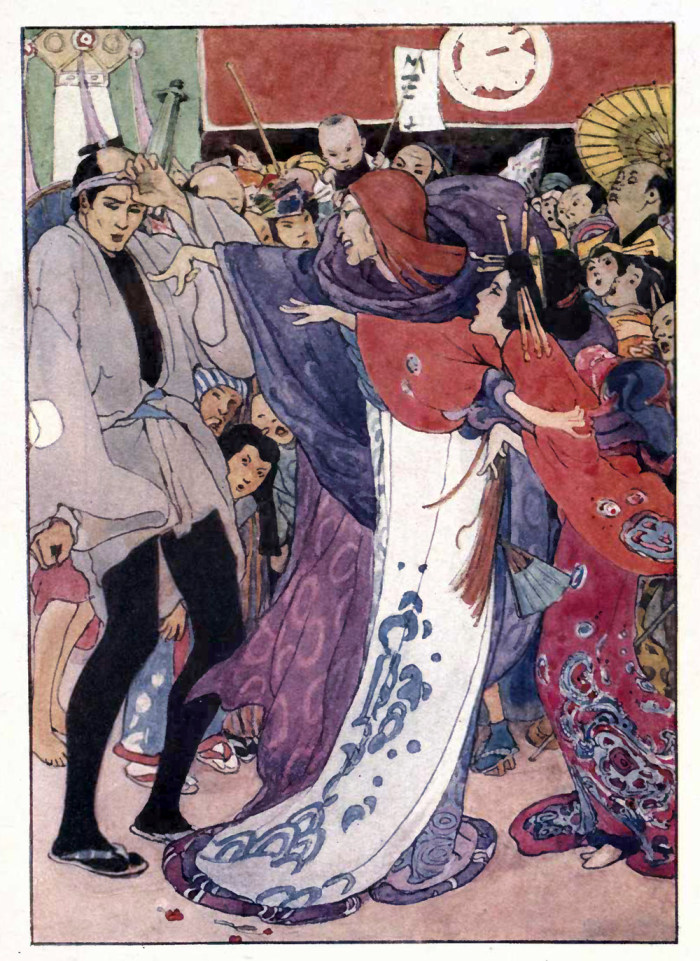

“ALAS, MY POOR LITTLE BRIDE THAT WAS TO BE” (p. 74)

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN.

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND GRIGGS (PRINTERS), LTD.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

Some of those who owe many a delightful hour to the genius of Sir William S. Gilbert may be interested in hearing how this book came to be written. In the pre-war days, that now seem so dim and distant, it occurred to his publisher that the story of “The Mikado,” told afresh by its author, would be welcomed by many of his admirers.

Sir William Gilbert accepted the project with even more than his usual geniality, and many talks about it with him will always be remembered by those who had the good fortune to be present.

That its publication has been so long delayed must be attributed mainly to the difficulties which have obstructed the production of books, especially those with coloured illustrations, during the last seven years.

But the evidence of never-failing popularity which recent revivals of the Savoy Operas have afforded, suggests that this last literary work of Sir W. S. Gilbert should be no longer withheld from the public, and it is now offered to his devotees, with fresh illustrations by Miss Alice B. Woodward, whose talented work and sympathetic rendering of all that is humorous and fanciful have made her known to a wide circle of admirers.

D. O’C.

| PAGE | ||

| Chapter | I | 1 |

| II | 33 | |

| III | 46 | |

| IV | 60 | |

| V | 74 | |

| VI | 90 |

| Coloured | |

| PAGE | |

| “Alas, my poor little bride that was to be” | Frontispiece |

| Their eyes met | 7 |

| “Pish-Tush, run him off” | 41 |

| He saw Yum-Yum enter the garden | 47 |

| “I claim my perjured lover, Nanki Poo” | 65 |

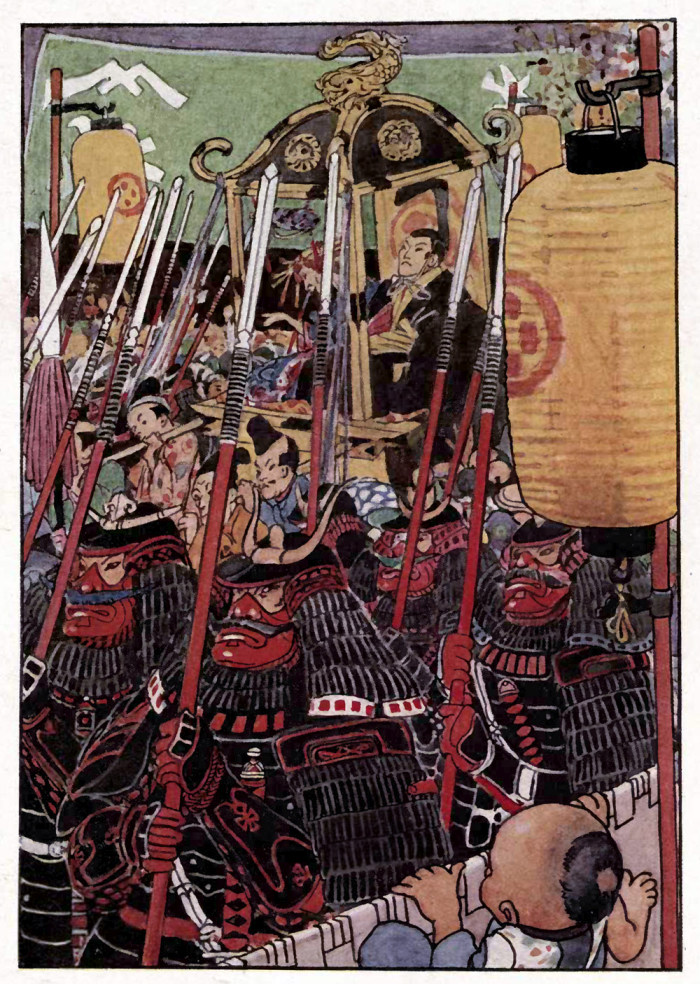

| A troupe of warriors in black and red armour | 93 |

| Black and White | |

| Pooh Bah and part of the family tree | 19 |

| Pooh Bah sobbed as he stooped to pick up a halfpenny | 26 |

| “Why that’s never you” | 38 |

| “That’s absurd,” said Koko | 53 |

| “Think you had better succumb-cumb-cumb” | 68 |

| “What do you mean?” asked Koko in great alarm | 86 |

| “I bared my big right arm” | 98 |

| “Then we’ll make it after lunch” | 106 |

| “Oh, I’m a silly little goose” | 112 |

| At all events he appeared to be satisfied | The End |

t has recently been discovered

that Japan is a great

and glorious country whose

people are brave beyond all

measure, wise beyond all telling,

amiable to excess, and

extraordinarily considerate to

each other and to strangers.

This is the greatest discovery

of the early years of the

twentieth century, and is

one of the results of the tremendous lesson the

Japanese inflicted on the Russians who attempted

to absorb a considerable portion of Manchuria a

few years ago. The Japanese, however, attained

their present condition of civilization very gradually,

and at the date of my story they had peculiar tastes,

ideas and fashions of their own, many of which they

discarded when they found that they did not coincide

with the ideas of the more enlightened countries of

Europe. So if my readers are of opinion (as they

very likely will be) that some of their customs, as

they are revealed in this story, are curious, odd or

ridiculous, they must bear in mind that the Japan

of that time was very unlike the Japan of to-day. It

is important to bear this in mind, because our

Government being (in their heart of hearts) a little

afraid of the Japanese, are extremely anxious not to

irritate or offend them in any way lest they should

come over here and give us just such a lesson as

they gave the Russians a few years ago. My readers

will understand that this fear is not entertained by

the generality of inhabitants of Great Britain and

Ireland who, as a body, are not much afraid of any

nation; it is confined mainly to the good and wise

gentlemen who rule us, just now, and whose wishes

should consequently be respected.

t has recently been discovered

that Japan is a great

and glorious country whose

people are brave beyond all

measure, wise beyond all telling,

amiable to excess, and

extraordinarily considerate to

each other and to strangers.

This is the greatest discovery

of the early years of the

twentieth century, and is

one of the results of the tremendous lesson the

Japanese inflicted on the Russians who attempted

to absorb a considerable portion of Manchuria a

few years ago. The Japanese, however, attained

their present condition of civilization very gradually,

and at the date of my story they had peculiar tastes,

ideas and fashions of their own, many of which they

discarded when they found that they did not coincide

with the ideas of the more enlightened countries of

Europe. So if my readers are of opinion (as they

very likely will be) that some of their customs, as

they are revealed in this story, are curious, odd or

ridiculous, they must bear in mind that the Japan

of that time was very unlike the Japan of to-day. It

is important to bear this in mind, because our

Government being (in their heart of hearts) a little

afraid of the Japanese, are extremely anxious not to

irritate or offend them in any way lest they should

come over here and give us just such a lesson as

they gave the Russians a few years ago. My readers

will understand that this fear is not entertained by

the generality of inhabitants of Great Britain and

Ireland who, as a body, are not much afraid of any

nation; it is confined mainly to the good and wise

gentlemen who rule us, just now, and whose wishes

should consequently be respected.

Many years ago (I won’t say how many because I don’t know) Japan was ruled by a great and powerful Mikado, and a Mikado in those days was regarded as four-fifths a King and one-fifth a god. It has recently been decided that there is less of the god in him than people originally supposed, and he is now regarded simply as an absolute monarch; but at the time of my story the mistake that his subjects made as to how he was put together had not been discovered.

If the existing Mikado had one fault (mind, I don’t say that he had), it was a habit of punishing every mistake, however insignificant, with death, and this caused him to be regarded with a kind of respectful horror by his subjects at large. But it must be remembered that he lived a long time ago, and no Mikado of the present day would ever think of doing anything of the kind.

Now, in those days there was a certain musician called Nanki Poo, who played the second trombone in the Purple Tartarian Band, and the Purple Tartarian Band was engaged for the season as the Town Band of a popular seaside resort called Titipu, and Titipu was the capital of an important province called Toki-Saki. The Town Band used to play every morning at the end of the pier, and it was customary for all the visitors at Titipu to stroll up and down the pier, after bathing, just as they do to-day at Brighton or Weymouth. One of his audience was a beautiful young girl called Yum-Yum, who was betrothed, quite against her will, to her guardian Koko, a cheap advertising tailor in a large way of business. “Yum-Yum” means, when translated, “The full moon of delight which sheds her remarkable beams over a sea of infinite loveliness, thus indicating a glittering path by which she may be approached by those who are willing to brave the perils which necessarily await the daring adventurers who seek to reach her by those means,” which shows what a compact language the Japanese is when all these long words can be crammed into two syllables—or rather, into one syllable repeated. Personally I should say that this description was a little high-flown for a school-girl home for the holidays, however pretty she might be, but like most first names, it was given to her when she was a baby and expressed nothing more than her fond parents’ hopes that she would eventually grow up to deserve it, and Yum-Yum was after all a very attractive young lady. Now Yum-Yum, who had a delicate ear for music, detected a quality in Nanki Poo’s performance on the second trombone which plainly distinguished him from the very inferior artist who played the first trombone, and who, from motives of professional jealousy, blew upon his instrument with all his might in order to divert attention from Nanki Poo to himself. But this ill-natured man defeated his own object, for though Nanki Poo, as second trombone, had nothing to do but to play

Amorosamente, ma non troppo

over and over again while his jealous superior played the air, Nanki’s “Too, too, too” was given with such tender delicacy and with such an exquisite appreciation of the precise shade of sentiment intended to be conveyed by the composer, that the crowd listened to him with tears in their eyes and simply regarded the first trombone, who only played the air, as an interfering and self-asserting busybody. This was especially the case when “Home, sweet Home” was played, for after he had blown at “Home, sweet Home” as loud as he could, everybody wished he would go there and leave them at liberty to concentrate their attention on Nanki Poo’s delightful “Too, too, too” without interruption.

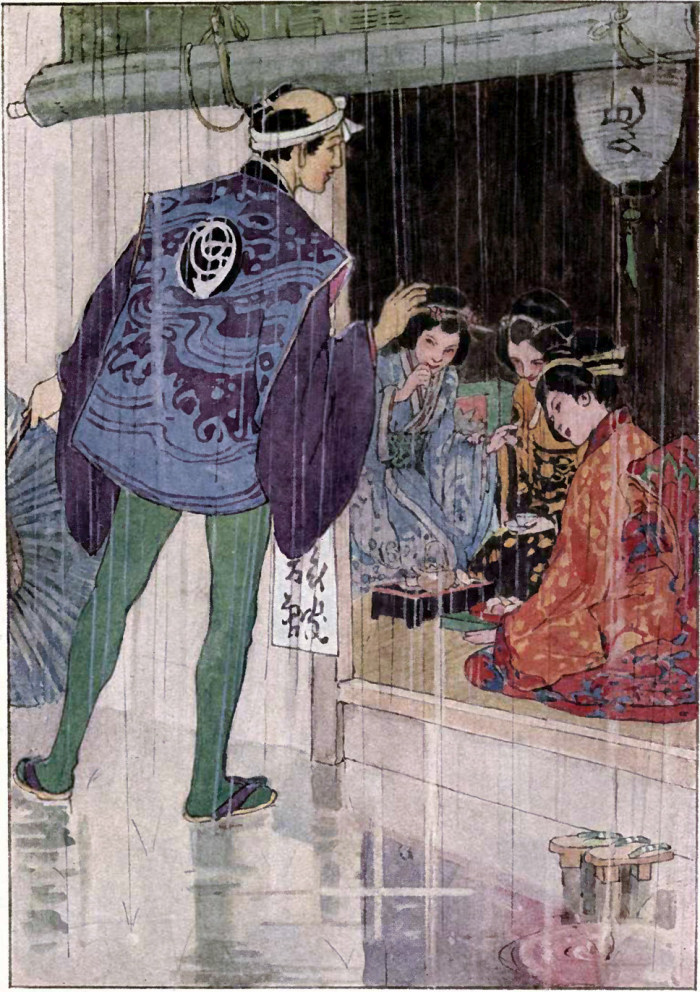

Notwithstanding the fact that she had been forcibly betrothed to her guardian, Yum-Yum, who at first was fascinated by Nanki Poo’s performance, ended by being fascinated by Nanki Poo himself; and this shows what a sensible girl Yum-Yum was. If a young lady is to yield to fascination at all, it is much wiser to begin by being fascinated by a gentleman’s beautiful work and then transfer her admiration to the gentleman who created it, than to begin by being fascinated by the gentleman before she knows whether he is able to create any beautiful work at all. Now Nanki Poo was such a conscientious musician that he devoted the whole of his attention to rendering expressively the simple but touching music he had to play, and never by any chance did he allow his beautiful purple eyes (which exactly matched his uniform) to wander from the music paper on which his notes were inscribed; so it came to pass that while Yum-Yum was engaged in the act of transferring her admiration from his work to himself, Nanki Poo was quite unconscious of the effect that he had created. But one happy day while the band was playing as usual at the end of the pier, a drenching shower of rain fell and Nanki Poo ran for shelter, with several others, under a refreshment pavilion in which such attractive delicacies as fried snails and scraped shark’s fin were sold at a reasonable rate; and there he saw Yum-Yum, who had also sought protection from the heavy downpour. Their eyes met, and Nanki Poo was quite as much fascinated by Yum-Yum as Yum-Yum had, for many weeks past, been fascinated by him. From that moment his performance on the second trombone perceptibly deteriorated. His “Too, too, too” was given carelessly and wandered into several keys, for he was always on the look-out for Yum-Yum, and when his eyes met hers the three beautiful notes with which he was entrusted were scarcely recognizable. The First Trombone came into favour with the crowd once more, and Nanki Poo’s performance ceased to be generally attractive to the audience at large. Eventually the Titipu season came to an end, but before the Purple Tartarians left for another part of the country, Nanki Poo, in the course of another obliging shower, contrived to tell Yum-Yum of the affection he entertained for her, and I need hardly describe her distress when she told him, with many sobs and endless tears, not only that she was betrothed, against her will, to be married to her undesirable guardian, but that their marriage was to take place in a year’s time, as soon as her education at her Finishing School was completed. As the whole band had to fulfil an engagement at a distant part of the country, Nanki Poo and Yum-Yum were necessarily separated. Yum-Yum returned to school, that she might continue her preparations for the Matriculation Examination at the University of Tokio, and, engaged as she was in these absorbing pursuits, she had little time to devote to memories of Nanki Poo, who eventually passed almost out of her mind. Nanki Poo, upon whose sensitive heart Yum-Yum had made an indelible impression, had no Matriculation Examination to distract his thoughts, and so it happened that when his engagement with the Purple Tartarians came to an end, he found himself without any settled means of gaining a livelihood. So he bought a kind of cheap Japanese banjo, as being easier to carry than a trombone, and earned a poor subsistence by playing and singing at tea houses and other places of rest and refreshment.

THEIR EYES MET

Now the Mikado (who after all was a sensible monarch in some respects) had issued a decree that any persons who were guilty of the vulgar and detestable offence of scribbling their obscure names upon Public Monuments should forthwith be beheaded, and Nanki Poo, in the course of his travels, learnt to his delight, that one of the first to incur this serious punishment was Yum-Yum’s guardian, Koko, the cheap tailor of Titipu, who had written “Try Koko’s fifteen shilling suits” on a highly venerated statue of Buddha, their favourite deity. So Nanki Poo packed up his banjo and without a moment’s delay set off on foot for Titipu in order to claim Yum-Yum’s hand in marriage, now that she was likely to be free to give it to him.

The inhabitants of Titipu were greatly agitated at the fate that had befallen Koko, not only because it brought forcibly to their minds the fact that any one of them might be subjected to a similar punishment for really insignificant little mistakes such as any of us might make in a moment of forgetfulness; but also because the town of Titipu was so entirely free from anything like crime that when the late Lord High Executioner retired on a pension at the respectable age of ninety-eight, it was not thought worth while to appoint a successor. It is true that office was the highest dignity that a citizen could attain, yet the salary attached to it was so enormous that, in the interests of public economy, it was thought better to leave it vacant until occasion arose for a decapitation, when it would be quite time to fill it up. Now, however, the occasion had arisen, and the question was, what was to be done? The Town Council of Titipu met several times to consider it, and eventually they came to a decision, which was that they could not do better than confer the post of Lord High Executioner on Koko himself, because, as they reasoned very ingeniously:

(1). All criminals sentenced to death must be executed in the order in which they are sentenced.

(2). Koko is the next in order to be executed.

(3). If we appoint him Lord High Executioner he cannot behead anybody else until he has beheaded himself.

(4). But a man cannot behead himself.

(5). Therefore he can never behead anybody else, and we are all quite safe and can do exactly as we please, which is an uncommonly jolly state of things.

So as soon as the Town Council had arrived at this sensible decision they commanded the inhabitants to assemble in the Market Place of Titipu in order that Koko, arrayed in his new robes of office, might be presented to them. I should state that he had already been appointed for several weeks, but his robes took a long time to embroider.

It was a great day for Titipu. Flags were hung out everywhere—a delicious kind of boiled seaweed was served out gratuitously to everyone (there were very few, however) who applied for it, an apple and a bun were presented to all the Board School children, and all the fountains in the city ran with weak tea. Little Japanese fireworks, such as you find in crackers at Christmas parties, were discharged in all directions, and thousands of halfpence were thrown among the crowd to be scrambled for. A great dignitary called Pooh Bah who, among many other things, was Chairman of the Town Council (and of whom you will read a good deal presently), formally introduced Koko (who was arrayed in magnificent robes of black and gold and carried an enormous sword, six feet long, which was his badge of office), and the people received him with shouts of “Banzai, Banzai!” which is Japanese for “Hip, hip, hurrah,” and sang, in chorus, the following beautiful lines:

Behold the Lord High Executioner

A personage of noble rank and title!

A dignified and potent Officer

Whose duties are particularly vital.

Defer—defer

To the Lord High Executioner!

To which Koko replied:

Taken from the county jail

By a set of curious chances,

Liberated then on bail

On my own recognizances,

Wafted by a favouring gale,

As one sometimes is in trances,

Surely never had a male

Under such like circumstances

So adventurous a tale

Which may rank with most romances!

Then he made a little speech, which was really an echo of one of his trade circulars.

“Gentlemen, I am much touched by this reception. I can only trust that by strict attention to business I shall ensure a continuance of those favours which it will ever be my study to deserve. In the highly improbable event of my ever being called upon to act professionally, I am happy to think that there will be no difficulty in finding plenty of people whose deaths will be a distinct gain to society at large.” And then he sang the following song, which he had composed that very morning:

KOKO’S SONG

As some day it may happen that a victim must be found,

I’ve made a little list—I’ve made a little list—

Of inconvenient people who might well be underground,

For they never would be missed—they never would be missed.

The donkey who of nine-times-six and eight-times-seven prates,

And stumps you with enquiries on geography and dates,

And asks for your ideas on spelling “parallelogram,”

All narrow-minded people who are stingy with their jam,

And the torture-dealing dentist, with the forceps in his fist—

They’d none of them be missed—they’d none of them be missed.

There’s the nursemaid who each evening in curlpapers does your hair

With an aggravating twist—she never would be missed—

And tells you that you mustn’t cough or sneeze or yawn or stare—

She never would be missed—I’m sure she’d not be missed.

All those who hold that children shouldn’t have too much to eat,

And think cold suet pudding a delicious birthday treat,

Who say that little girls to bed at seven should be sent,

And consider pocket money isn’t given to be spent,

And doctors who on giving you unpleasant draughts insist—

They never would be missed, they’d none of them be missed.

Then the teacher who for hours keeps you practising your scales

With an ever-aching wrist—she never would be missed—

And children, too, who out of school are fond of telling tales—

They never would be missed—I’m sure they’d not be missed.

All people who maintain (in solemn earnest—not in joke)

That quantities of sugar-plums are bad for little folk,

And those who hold the principle, unalterably fixed,

That instruction with amusement should most carefully be mixed;

All these (and many others) I have placed upon the list,

For they never would be missed—never, never would be missed!

Of course this song was only Koko’s fun (for he was naturally too delighted at his sudden promotion from the condition of a convict under sentence of death to the exalted position of Lord High Executioner to take anything seriously), and it was so regarded by his audience, who were not so unfeeling as to desire that a severe punishment should be inflicted upon people who, after all, were only doing a kind of duty in a rather injudicious manner. Well, when the people had enjoyed Koko’s little joke (the Japanese are a simple people who are very easily amused), Koko proceeded at once to the palace which had been assigned to him as an Official Residence, followed by the populace at large. The wealthy but thrifty Pooh Bah, however, remained in the Market Place in order to pick up any of the halfpence which had been thrown among the crowd and which might have escaped their observation. This he did partly with the view of humiliating his family pride, but principally because his maxim was that, as regards a halfpenny, you never could tell when it would come in handy.

Now this Pooh Bah may be described without any hesitation as one of the most remarkable characters in ancient or modern history. He was not a clever man—he was, in fact, an intolerably conceited donkey—but he was such a remarkable donkey that his very donkeydom entitled him to the affectionate respect of his fellow townsmen as being infinitely more remunerative than the very highest form of educated intelligence could possibly be. Personally I would rather be a very wise man than a stupid, but if I couldn’t be a very wise man (I have tried and I find I can’t) I would rather be so stupid as to excite wonder and admiration on account of the extraordinary and exceptional quality of my stupidity. I do not mean to suggest that I am right in holding this opinion, but if there is one character that I dislike more than another it is that particular kind of average person which I happen to be. Well, Pooh Bah was, as I have said, a remarkable character. He got it into his thick head that he was the last descendant of a family of extraordinary antiquity, and this was a matter of which he was so stupid as to be inordinately proud. Whenever he saw, or fancied he saw, the faintest possible resemblance to himself in the personal appearance of any eminent historical personage, he at once concluded that that historical personage must necessarily be one of his ancestors. So he collected all the portraits of dead celebrities that he could find, and managed to detect some resemblance to himself in all of the most illustrious of them. Thus he worked his way backwards through mankind until he had exhausted all the specimens he could find, and having done this he fell back upon the animal kingdom, and by means of fancied resemblances, traced his ancestry through Gorillas, Ourang-outangs, Barbary Apes, Capuchin Monkeys, Marmosets, Lemurs, Flying Squirrels, Bats, Canary Birds, Butterflies, Moths, Ladybirds, Black Beetles, Cheese-Mites, Jelly-fish, Coleoptera, Rotifera, Bacteria, Tollolleria, Twaddleria, Nonsenseria, Absurderia, Ridiculeria and thousands of other queer little creatures whose names I entirely forget (but could easily invent and no one but Sir Edwin Ray Lankester, K.C.B., would be the wiser) until he came at last to a Protoplasmal Primordial Atomic Globule (exactly like him) which he found reclining in great state and dignity at the business end of an amazingly powerful microscope; and as fifty million of these gentry can be comfortably accommodated on the point of a needle, he considered (and I think that in this he showed a glimmer of sense) that it would be pedantic to pursue his researches any further. His Family Tree was quite a curiosity in itself, and I wish I could reproduce it here, but as it was about fifteen miles long it would make this book too bulky, and it’s bulky enough already, goodness knows.

But this was only one phase of his complicated character. He was sufficiently intelligent to know that it was not only very illogical but extremely wrong to be inordinately proud of his long family descent (for he had done nothing towards it except to be the last of them all, which wasn’t much), so he virtuously resolved to mortify this family pride at every opportunity that presented itself. Consequently when all the High Officers of State (who were also very proud people) resigned in a body because they would not bring themselves to serve under a Lord High Executioner who had formerly been nothing more than an advertising tailor, Pooh Bah unhesitatingly accepted all their offices, to which extremely handsome salaries happened to be attached. Of course his income from these appointments was enormous, but that circumstance was in itself a dreadful indignity, because it constituted him a salaried minion, and for all salaried minions and other people who earned their own living he entertained an unbounded contempt. He was undoubtedly a silly, because what he did was open to misconstruction, but in doing it he meant well, and moreover it paid.

As Pooh Bah was busy mortifying his family pride by looking for overlooked halfpence, Nanki Poo, who had just arrived at Titipu in search of his beloved Yum-Yum, accosted him, and I ought to explain that it was the rule in Titipu that when you addressed a gentleman in prose he had to reply to you in prose, but when you addressed him in verse he had to reply in verse. So Nanki Poo sang:

Good nobleman, I pray you tell me

Where an enchanting maiden dwelleth

Who’s named Yum-Yum, the ward of Koko?

In pity speak—Oh, speak, I pray you!

To which Pooh Bah replied:

Why who are you who ask this question?

And Nanki Poo proceeded at once to sing a song descriptive of himself—a song which he had ready because he had often sung it at tea-houses and other places of entertainment:

A Wandering Minstrel I,

A thing of shreds and patches,

Of ballads, songs and snatches

And dreamy lullaby.

My catalogue is long,

Through every passion ranging,

And to your humours changing

I tune my supple song!

Are you in sentimental mood?

I’ll sigh with you.

Oh, willow! willow!

On maiden’s coldness do you brood?

I’ll do so too.

Oh, willow! willow!

I’ll charm your willing ears

With songs of lovers’ fears,

While sympathetic tears

My cheek bedew,

Oh, willow! willow!

(Then he changed the tune.)

But if patriotic sentiment is wanted,

I’ve patriotic ballads cut and dried,

For wher’er our country’s banner may be planted,

All other local banners are defied.

Our warriors, in serried ranks assembled,

Never quail—or they conceal it if they do;

And I shouldn’t be surprised if people trembled

Before the mighty troops of Titipu!

(He sang the verse that follows to a rollicking sea-tune.)

And if you call for a song of the sea,

We’ll heave the capstan round,

With a “yeo heave oh!” for the wind is free,

Her anchor’s a-trip and her helm’s a-lee,

Hurrah for the homeward bound!

To lay aloft when it blows and snows

May tickle a landsman’s taste,

But the happiest hour a sailor knows

Is when he’s down

At an inland town,

With his Nancy on his knee, yeo ho!

And his arm around her waist!

Then man the capstan—off we go,

As the fiddler swings us round.

With a “yeo heave ho!”

And a rumbelow,*

Hurrah for the homeward bound!

“That’s a very nice song,” said Pooh Bah, “but it’s too long. I was tired of it ever so long before it was finished.”

“I’ll sing it again with a verse left out, if you like,” said Nanki Poo, who was anxious to conciliate so important a person.

“Well, try,” said he, and Nanki Poo sang it again with the sentimental verse omitted.

“That’s much better,” said Pooh Bah; “I was not nearly so bored that time. Now try it without the patriotic verse.”

And Nanki Poo sang it without the patriotic verse.

“I quite enjoyed that,” said Pooh Bah; “now omit the nautical stanza.”

Nanki Poo did so, though he was getting rather tired.

“That’s delightful!” exclaimed Pooh Bah. “Now try it without the introductory verse.”

“But that would leave nothing to sing,” said Nanki Poo.

“Exactly my idea of a song!” said Pooh Bah, greatly tickled at the success of his little practical joke. “So much obliged to you. And now to business. What do you want with Yum-Yum?”

“I’ll tell you,” said Nanki Poo. “A year ago I loved her and I discovered that she loved me, although she was betrothed, entirely against her will, to her guardian Koko. As a man of honour, I gave up all hope of her and left the town broken-hearted. Judge of my delight when I heard, a short time ago, that Koko had been condemned to be beheaded for defacing a public monument. I hurried back at once in the hope of finding Yum-Yum at liberty to listen to my protestations.”

“It is quite true,” replied Pooh Bah, “that Koko was so condemned, but he was reprieved at the last moment and raised to the exalted rank of Lord High Executioner under the following remarkable circumstances:

Our great Mikado, virtuous man,

When he to rule our land began,

Resolved to try

A plan whereby

His people might be steadied,

So he proclaimed a statute new

That all misguided people who

Did anything they shouldn’t do

Should forthwith be beheaded.

His stern decree, you’ll understand,

Caused great dismay throughout the land,

For young and old

And shy and bold

Were equally affected:

The gentleman who snubbed his wife

Or ate green peas with blade of knife

Was straight condemned to lose his life—

He usually objected.

So we released on heavy bail

This Koko from the county jail

(Whose head was next

On good pretext

Condemned to be mown off),

And made him headsman, for we said

“Who’s next to be decapited

Cannot cut off another’s head

Until he’s cut his own off.”

And we are right, I think you’ll say,

To argue in this kind of way,

And I am right,

And he is right,

And all is right—too looral lay!

“Koko released and appointed Lord High Executioner!” exclaimed Nanki Poo in broken-hearted dismay. “Why, that’s the highest rank a citizen can attain!”

“It is,” replied Pooh Bah. “Our logical Mikado, seeing no moral difference between the dignified Judge who condemns a criminal to die and the industrious mechanic who carries out the sentence, has rolled the two offices into one, and every Judge is now his own Executioner.”

“But,” said Nanki Poo, who saw the brilliant Order of the Potted Geranium sparkling on Pooh Bah’s bosom, “how good of you, who are evidently a Nobleman of the highest rank, to condescend to tell all this to me, a mere strolling minstrel!”

“You’d think so indeed if you knew all,” replied Pooh Bah. “I am, in point of fact, a particularly haughty and exclusive person of pre-Adamite ancestral descent. My family pride is something inconceivable; I’m ashamed of this weakness, but I can’t help it. I was born sneering. Nevertheless, I struggle hard to overcome this defect. I mortify my pride on every possible occasion. When all the officers of State resigned in a body because they were too proud to serve under a retired tailor, did I not unhesitatingly accept all their posts at once? It is consequently my degrading duty to serve this contemptible upstart as First Lord of the Treasury, Lord Chief Justice, Commander-in-Chief, Lord High Admiral, Master of the Buckhounds, Lord of the Bedchamber, Gold Stick in Waiting, Archbishop of Titipu, and Lord Mayor, both acting and elect. And at a salary! In point of fact, at several salaries! A Pooh Bah paid for his services! I a salaried minion! But I do it! It revolts me, but I do it!”

A great sob rose to Pooh Bah’s throat as he stooped to pick up a halfpenny, which had hitherto escaped his observation.

“It does you credit,” said Nanki Poo, who was too simple to see that Pooh Bah was really a very contemptible character.

“But I don’t stop at that,” continued Pooh Bah; “I dine with middle-class people on reasonable terms. I dance at cheap suburban parties for a moderate fee. I accept refreshment at any hands, however lowly. I also retail State Secrets at a very low figure. For instance, any further information about Yum-Yum would come under the head of a State Secret.”

Nanki Poo took the hint and gave him the few coins in his possession. Pooh Bah (who had been leading up to this) flushed purple with shame and humiliation.

“Another insult!” said he, weighing the coins in his hand, “and, I think, a light one!” Nevertheless he proceeded to earn his tip by singing the following song:

Young man, despair,

Likewise go to,

Yum-Yum the fair

You may not woo.

It will not do,

I’m sorry for you,

You very imperfect ablutioner!†

This very day

From school Yum-Yum

Will wend her way

And homeward come,

With beat of drum

And a rum-tum-tum,

To wed the Lord High Executioner!

And the brass will crash,

And the trumpets bray,

And they’ll cut a dash

On their wedding day.

From what I say you may infer

It’s as good as a play to him and her;

She’ll toddle away as all aver,

With the Lord High Executioner

It’s a hopeless case

As you may see,

And, in your place,

Away I’d flee;

But don’t blame me,

I’m sorry to be

Of your pleasure a diminutioner.

They’ll vow their pact

Extremely soon,

In point of fact

This afternoon

Her honeymoon

With that buffoon

At seven commences, so you shun her!

Nanki Poo was terribly upset by Pooh Bah’s news about Yum-Yum, and he went away in the most disconsolate condition imaginable. Pooh Bah, who considered that he had fully earned his tip, resumed his search for overlooked halfpence with such intentness (he had found three) that he did not notice the approach of Koko who had to tap him on the shoulder to attract his attention.

“Pooh Bah,” said Koko, “I want to consult you on a matter of some importance.”

“I am all ears,” replied Pooh Bah, which in one sense was true enough.

“It seems that the festivities in connection with my approaching marriage with Yum-Yum (who will arrive to-day) must last a week. I should like to do the thing handsomely, and I want to consult you as to the amount I ought to spend upon it.”

“Certainly,” said Pooh Bah. “But in which of my capacities do you wish to consult me? As First Lord of the Treasury, Lord Chamberlain, Attorney General, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Privy Purse or Private Secretary?”

Koko considered for a moment.

“Suppose we say as Private Secretary.”

“Speaking as your Private Secretary I should say that, as the city will have to pay for it, don’t stint yourself—do it well.”

“Exactly,” said Koko. “As the city will have to pay for it. That is your advice?”

“As Private Secretary,” said Pooh Bah. “Of course you will understand that as Chancellor of the Exchequer I am bound to see that due economy is observed.”

“Oh,” said Koko, rather crestfallen. “But you said just now ‘don’t stint yourself, do it well.’ ”

“As Private Secretary,” replied Pooh Bah.

“And now you say that due economy must be observed.”

“As Chancellor of the Exchequer.”

“I see,” said Koko, “that’s awkward.” Then an idea occurred to him.

“Come over here, where the Chancellor can’t hear us,” said Koko, leading him round the corner of the square. “Now, as my Solicitor, how do you advise me to deal with this difficulty?”

“Oh, as your Solicitor,” replied Pooh Bah, “I should have no hesitation in saying ‘chance it.’ ”

“Thank you,” said Koko, shaking his hand. “That settles it—I will.”

“If it were not that as Lord Chief Justice I am bound to see that the law isn’t violated.”

“I see; that’s awkward again. Come over here where the Chief Justice cannot hear us,” leading him down the second turning to the left. “Now then, as First Lord of the Treasury?”

“Of course as First Lord of the Treasury,” said Pooh Bah, “I could propose a special vote that would cover all expenses if it were not that, as Leader of the Opposition, it would be my duty to resist it tooth and nail. Or as Paymaster-General I could so cook the accounts that as Lord High Auditor I should never discover the fraud. But then as Archbishop of Titipu it would be my duty to denounce my dishonesty and give myself into my own custody as First Commissioner of Police.”

“That’s more awkward still,” said Koko, quite depressed by the many difficulties that were presented to him.

Pooh Bah was not adamant. His gentle heart was touched by Koko’s embarrassment.

“I don’t say,” said Pooh Bah, “that all these important people could be squared; but it is right to tell you that they wouldn’t be sufficiently degraded in their own estimation unless they were insulted by a very considerable bribe.”

Koko was a little relieved.

“The matter shall have my careful consideration,” said he, giving him all the money he had about him. “But see—my beautiful Yum-Yum and her bridesmaids approach, and any little compliment on your part, such as an abject grovel in a characteristic Japanese attitude, would be esteemed a favour.”

“No, no,” said Pooh Bah, “grovels are extra. No money no grovel.” And as Koko had no more to give him, the grovel had to be dispensed with.

|

I have no idea what a “rumbelow” may be. No doubt it is some nautical article that is extremely useful on board-ship, for it is so often alluded to in sea-songs. It seems to hold the same place in a sea-song that the “old plantation” does in negro minstrelsy. |

|

The Japanese are an extremely clean people, and Pooh Bah was honestly shocked to find that Nanki Poo’s long march had left its traces on his person. |

um-Yum’s Finishing

School had broken up for

the holidays, and Yum-Yum

was to return at once to Titipu

to be married, very unwillingly,

to her guardian Koko, for

whom she had no affection

whatever. In Japan, as in England, a young lady who is

under age cannot be married without her guardian’s

consent, and as Koko would not consent to her

marrying anybody but himself, she had to marry him

if she wanted to be married to anyone at all.

um-Yum’s Finishing

School had broken up for

the holidays, and Yum-Yum

was to return at once to Titipu

to be married, very unwillingly,

to her guardian Koko, for

whom she had no affection

whatever. In Japan, as in England, a young lady who is

under age cannot be married without her guardian’s

consent, and as Koko would not consent to her

marrying anybody but himself, she had to marry him

if she wanted to be married to anyone at all.

Yum-Yum, as a bride-that-was-to-be, was naturally an object of intense interest to all her schoolfellows, and as she was extremely popular with them on account of her amiability and (properly restricted) sense of fun, they all begged to be allowed to be her bridesmaids. Yum-Yum, who was a most good-natured girl, readily assented to this suggestion, so the day after breaking-up they all travelled together to Titipu in three long omnibuses, with their luggage on the roof, because as she was to be married that evening there was necessarily no time to be lost.

Yum-Yum and her bridesmaids arrived safely at Titipu and at once proceeded on foot to the courtyard in front of Koko’s Official Residence, where he was waiting, dressed in his most magnificent clothes, to receive them. Moreover he was attended by his retinue of nobles, including Pooh Bah, who as Archbishop of Titipu was to read the marriage ceremony.

The young ladies entered the courtyard, walking two and two, and singing this pretty song:

Comes a train of little ladies

From scholastic trammels free,

Each a little bit afraid is,

Wondering what the world can be!

Is it but a world of trouble—

Sadness set to song?

Is its beauty but a bubble

Bound to break ere long?

Are its palaces and pleasures

Fantasies that fade?

And the glories of its treasures

Shadows of a shade?

As nobody could guess the answer to these riddles, Yum-Yum, with her two dearest and most confidential friends (who were called Peep Bo and Pitti-Sing), came to the front and sang the following trio, which had been composed by the school musicmaster for the occasion:

Three little maids from school are we,

Pert as a school-girl well can be,

Filled to the brim with girlish glee;

Three little maids from school!

Everything is a source of fun;

Nobody’s safe for we care for none;

Life is a joke that’s just begun;

Three little maids from school!

Three little maids who all unwary

Come from a ladies’ seminary,

Freed from its genius tutelary!

Three little maids from school!

One little maid is a bride—Yum-Yum—

Two little maids in attendance come,

Three little maids is the total sum—

Three little maids from school!

From three little maids take one away,

Two little maids remain, and they

Won’t have to wait very long, they say—

Three little maids from school!

Three little maids who all unwary

Come from a ladies’ seminary,

Freed from its genius tutelary—

Three little maids from school!

Koko was very pleased with their trio, and even the solemn and haughty Pooh Bah was seen to smile. But he recollected that a smile was quite inconsistent with the dignity of twenty-eight of his most important public appointments, and consistent only with about three of the humblest of them—Court Jester, Licenser of Plays, and Editor-in-Chief of the Japanese Punch. There was a heavy majority against the smile and therefore, being a conscientious man, he effaced it at once and resumed his customary expression of solemn stupidity.

Koko came down the steps, with open arms, to receive Yum-Yum, who was not a little alarmed at this threat of affection.

“You’re not going to kiss me before all these people?” said she.

“Well,” said Koko, “that was the idea.”

Yum-Yum didn’t know much about these things, for she only knew what was taught in the Finishing School, and the Finishing School did not finish them quite as far as that. She turned to Peep Bo.

“It seems odd, doesn’t it?” whispered Yum-Yum.

“It is rather peculiar,” assented Peep Bo.

“Oh, it’s all right,” said Pitti-Sing. “Everything must have a beginning, you know.”

“Well,” replied Yum-Yum, “of course I know nothing about these things, but I’ve no objection if it’s usual.”

“Oh, it’s quite usual, I think,” said Koko, who, to make quite sure, appealed to Pooh Bah. “What do you say, Lord Chamberlain?”

Now the Lord Chamberlain was the highest authority on all points of propriety, and his decision in such matters was final. Pooh Bah reflected for a moment:

“I have known it done,” said he at last.

That settled the matter, and Koko kissed Yum-Yum on both cheeks to the infinite amusement of all the bridesmaids, who chuckled to each other in a rather unladylike manner.

“Thank goodness that’s over!” said Yum-Yum.

At this moment the three young ladies caught sight of poor Nanki Poo, who had managed to get into the courtyard with the crowd in order to have one last look at Yum-Yum before losing her for ever.

Yum-Yum saw him and recognized him at once.

“Why,” said she, running up to him, “that’s never you!”

You see at a Finishing School they teach you a great many polite accomplishments, but you are not taught grammar because you are supposed to know it before you go there, otherwise, instead of exclaiming “that’s never you!” she would probably have said: “Am I mistaken, or do I behold you once more?”

The other two young ladies (who had heard all about him from Yum-Yum) rushed up to him and all three began to speak at once, without any stops:

| Yum-Yum said: | Oh I am so glad—I haven’t seen you for ever so long and I’m right at the |

| Peep Bo said: | And have you got an engagement? Yum-Yum’s got one but she doesn’t like |

| Pitti-Sing said: | Now tell us all about the news because you go about everywhere and we’ve been |

| (Yum-Yum): | top of the school and have got three prizes and I’ve come home for good and I’m |

| (Peep Bo): | it and she’d ever so much rather it was you and I’ve come home for good and I’m |

| (Pitti-Sing): | at school, but thank goodness that’s all over now and we’ve come home for good and we’re |

| (Yum-Yum): | not going back any more! |

| (Peep Bo): | not going back any more! |

| (Pitti-Sing): | not going back any more! |

You can try if you like to say these three speeches at once as the girls did. I should think it was difficult because I can’t do it myself, and I know that anything that is too difficult for me to do must be very difficult indeed. But there’s no reason why you shouldn’t try—especially on a wet day, when you can’t go out and find it rather dull at home. If you can’t do it, and I can’t do it, it shows that three little school-girls put together are cleverer than you and I, because they could and did.

Nanki Poo was deeply touched to find that Yum-Yum had borne him in remembrance during the year of their separation, and he determined to make a final appeal to Koko’s commiseration. But just as he was about to throw himself at Koko’s feet, that gentleman, who had been not a little astonished at the welcome accorded to Nanki Poo by the three young ladies, said to them, rather drily:

“I beg your pardon. Will you present me?”

“Oh,” said all three at once. “This is the gentleman who——”

“One at a time, if you please,” said Koko.

“This,” said Yum-Yum, “is the gentleman who used to play so beautifully on the—on the——”

“On the Marine Parade,” said Peep Bo.

“Oh, indeed,” said Koko, as he uttered a long whistle with his pursed-up lips. “I am not acquainted with the instrument.”

Nanki Poo could be silent no longer.

“Sir,” said he, “I have the misfortune to love your ward Yum-Yum; she returns my affection and is entirely indifferent to yours. Oh, I know I deserve your anger, but I——”

“Anger?” said Koko. “Not a bit, my boy. Why I love her myself! I’m not so unreasonable as to quarrel with a man for agreeing with me. Charming little girl, isn’t she? Pretty eyes—nice hair—taking little thing, altogether. Very glad to have my opinion backed by a competent authority. Thank you very much. Good-bye. Pish-Tush, run him off.”

And Pish-Tush took him by the back of the neck with one hand and by the waist with the other and ran him out of the courtyard in the most undignified manner.

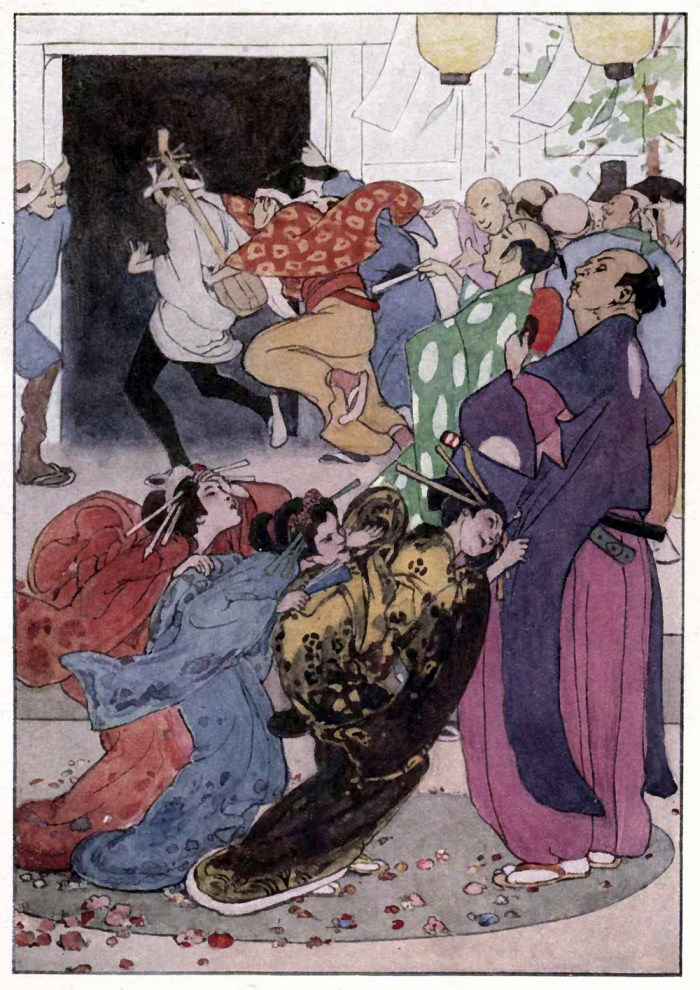

“PISH-TUSH, RUN HIM OFF”

In the meantime Yum-Yum, Peep Bo and Pitti-Sing had been devoting their attention to Pooh Bah, who stood absolutely motionless to express his contemptuous indifference to the impertinent curiosity of the young ladies. They had never seen anything like him before, and they were not quite sure that he wasn’t a piece of ingenious waxwork. One of them, to make sure, poked him in the ribs with her forefinger, which made him jump.

“It’s alive!” said she, starting back in alarm.

“Go away, little girls,” said Pooh Bah, whose dignity was terribly upset by this very unladylike action. “Can’t talk to little girls like you. Go away, there’s dears.”

Koko came to the rescue.

“Pooh Bah, allow me to present my bride-elect. It’s the one in the middle.”

“What do you want me to do to them?” said Pooh Bah, swelling with outraged importance. “Mind, I will not kiss them.”

“No, no,” replied Koko. “You shan’t kiss them. A little bow—a mere nothing. You needn’t mean it, you know.”

“It goes against the grain,” said Pooh Bah. “They are not young ladies, they are young persons.”

“Come, come,” said Koko, “make an effort, there’s a good nobleman.”

“Well I shan’t mean it,” replied Pooh Bah. And, comforting himself with this reflection, he made a tremendous effort as though he were trying to swallow a larger piece of Bath bun than he could conveniently manage.

“How de do, little girls—how de do?” And then he muttered to himself: “Oh, my Protoplasmal Ancestor!”

“That’s very good,” said Koko, encouragingly. “That’s really capital.”

The three young ladies were very much amused at Pooh Bah’s absurd pride. They were so ill-bred as to chuckle quite out loud, and I don’t think much of their Finishing School.

“I see nothing to laugh at,” said Pooh Bah, swelling with importance like an angry turkeycock. “It’s very painful to me to have to say ‘How de do, little girls’ to young persons. I’m not in the habit of saying ‘How de do, little girls’ to anybody under the rank of a stockbroker.”*

Koko was distressed at Pooh Bah’s evident annoyance.

“Don’t laugh at him,” whispered Koko to the girls. “He can’t help it—he’s under treatment for it.” Then, turning to Pooh Bah, he said: “Never mind them; they don’t understand the delicacy of your position.”

“We know how delicate it is, don’t we?” said Pooh Bah, who was very fierce by this time.

“I should think we did,” said Koko. “How a nobleman of your importance can do it at all is a thing I never could and never shall understand. Come with me and be rude to one of the servants. It will help to reconcile you to yourself.”

And off they went together, leaving Yum-Yum, Peep Bo and Pitti-Sing laughing heartily at their experience of a nobleman of the highest importance.

|

I don’t know why he drew the line at a stockbroker, unless it is that when a member of the aristocracy is ruined he generally goes on the Stock Exchange. |

oko and Yum-Yum were to be

married at sunset, and as the evening

approached Yum-Yum became very

sad indeed. Although she was not as

much interested in Nanki Poo as she

had been a year ago, nevertheless his

unexpected return to Titipu on the

very day of her intended marriage

with Koko seemed to make her still more unwilling

to unite herself to a man who was absolutely uninteresting

to her. She wandered forth into the shady

grounds of the Official Residence in order to think

it over and try to find some means of escaping the

unpleasant doom that Koko had prepared for her.

oko and Yum-Yum were to be

married at sunset, and as the evening

approached Yum-Yum became very

sad indeed. Although she was not as

much interested in Nanki Poo as she

had been a year ago, nevertheless his

unexpected return to Titipu on the

very day of her intended marriage

with Koko seemed to make her still more unwilling

to unite herself to a man who was absolutely uninteresting

to her. She wandered forth into the shady

grounds of the Official Residence in order to think

it over and try to find some means of escaping the

unpleasant doom that Koko had prepared for her.

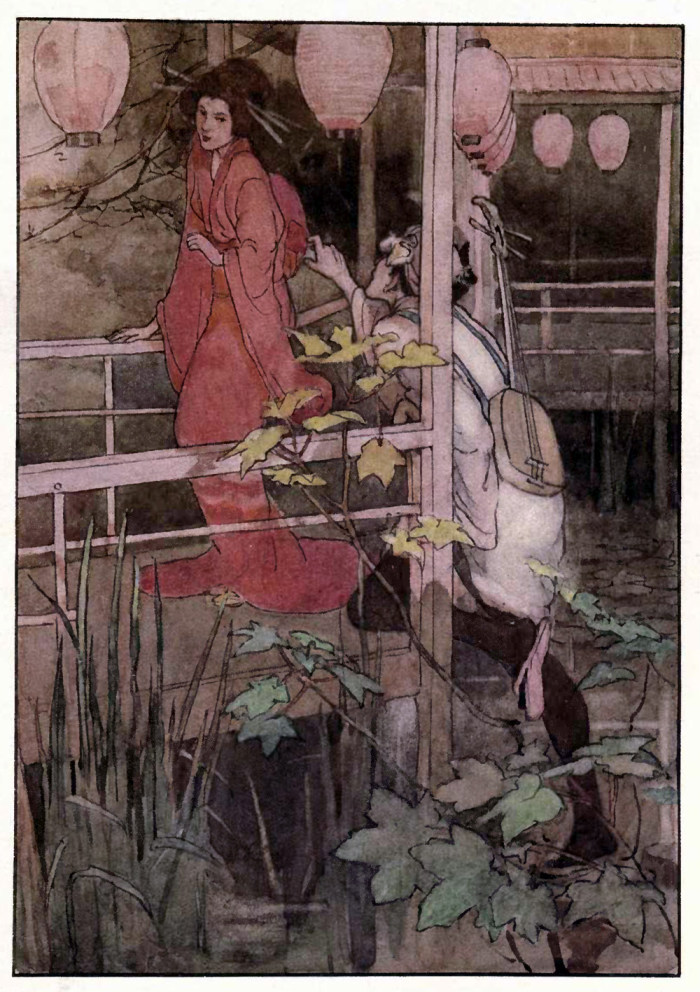

Now Nanki Poo was so absorbed by his distress at the prospect of Yum-Yum’s marriage that he kept hovering about the Residence all day long. He saw Yum-Yum enter the garden and he at once accosted her, for he had something to say that he thought might exercise a powerful influence over her movements.

HE SAW YUM-YUM ENTER THE GARDEN

“Yum-Yum,” said he, “I’m in a dreadful state of mind. I’ve travelled here night and day for three weeks in the belief that your guardian was to be beheaded, and now I find that he’s reprieved and that you are to be married to him this evening!”

“Alas, yes!” said Yum-Yum.

“But you do not love him?”

“Alas, no!”

“Then refuse to be married to him and be married to me instead.”

“Impossible,” said Yum-Yum. “It is true that I do not love Koko, but a wandering minstrel who sings and plays outside places of entertainment is hardly a fitting husband for the ward of a Lord High Executioner.”

Nanki Poo looked right and left to be quite sure that they were unobserved, while he made the important communication to which I have referred.

“What,” said he in an emphatic whisper, “if it should prove that, after all, I am no musician?”

“There!” said Yum-Yum, “I was certain of it directly I heard you play.”

This was sheer nonsense on Yum-Yum’s part, for she admired his playing beyond everything, but she never could resist an opportunity of being pert.

“Now do be serious for one moment,” said Nanki Poo. “What if it should prove that I am no other than the SON OF HIS MAJESTY THE MIKADO!”

“The son of the Mikado!” exclaimed Yum-Yum in great amazement. “The heir to the throne of Japan?”

“That is another way of putting it,” said Nanki Poo.

Yum-Yum fell on her knees and hit her forehead on the ground three times (but not too hard) to express her reverence for the exalted gentleman who had courted her.

“But why is your Highness disguised?” she exclaimed, “and what has your Highness done? And will your Highness promise never to do it again?”

“I’ll tell you,” said Nanki Poo. “Some years ago I had the misfortune to captivate Kati-sha, an elderly lady of my father’s Court. She, mistaking my customary politeness for an expression of affection, claimed me in marriage. My father, who is extremely strict in such matters, ordered me to marry her within a week or be beheaded that evening. That evening I fled, and, assuming the disguise of a Second Trombone, I joined the band in which you found me when I first had the happiness of seeing you.”

“I see,” said Yum-Yum, who was beginning to be much impressed by the exalted rank of her suitor. “I’ll think it over. Go away now and I’ll see what can be done. But to be quite candid, I don’t see how I am to get out of it.”

“Is there no hope?” said Nanki Poo.

“I’m afraid not,” said Yum-Yum. “But, nevertheless, hope up to a certain point, but don’t overdo it. Now go, for I hear Koko coming, and if he catches me talking to you it will vex him. Good-bye!”

And they rubbed their knees and bent their heads at each other, as was usual in Japan when two people parted. Nanki Poo leapt over the small boundary wall and vanished, while Yum-Yum went into the house just as Koko appeared.

“There she goes,” said Koko to himself. “To think how entirely my future happiness is wrapped up in that little parcel! Oh, Matrimony!”

He was going on to address a carefully prepared speech to Matrimony, when Pooh Bah and Pish-Tush entered hurriedly.

“Now then, what is it?” said Koko. “Can’t you see that I’m soliloquizing? You have interrupted an apostrophe, sir!”

“I beg your Highness’s pardon,” said Pish-Tush, “but we are the bearers of a letter from the Mikado.”

“A letter from the Mikado!” exclaimed Koko. “What can it be about?”

They all squatted on the ground, and Koko pressed the letter to his forehead in token of submission before he opened it.

“Ah, here it is at last,” said Koko as he read the letter with dismay. “The Mikado is struck by the fact that no executions have taken place in the province of Toki-Saki for many years, and he decrees that unless somebody is beheaded within a month, the city of Titipu shall be reduced to the rank of a village!”

“But that will involve us all in irretrievable ruin!” said Pish-Tush, who held a quantity of tramway shares.

“Absolute ruin!” exclaimed Pooh Bah, who as Lord High Architect had just accepted a valuable contract to build a cathedral.

“Yes,” said Koko, “there’s no help for it; I shall have to execute somebody. The only question is, who shall it be?”

“Well,” said Pooh Bah, “it seems unkind to say so, but as you’re already under sentence of death, everything points to you.”

“That’s absurd,” said Koko. “It has been already decided that a man cannot cut his own head off.”

“A man might try,” replied Pooh Bah.

“Even if you only succeeded in cutting it half off, that would be something,” said Pish-Tush.

“It would be taken as evidence of your desire to comply with the Imperial will,” observed Pooh Bah.

“No,” said Koko. “There I am adamant. As Lord High Executioner my reputation is at stake, and I can’t consent to embark on a professional operation unless I see my way to a successful result.”

“This professional conscientiousness is highly creditable to you,” remarked Pooh Bah, “but it places us in a very awkward position.”

“My good sir,” said Koko, a little nettled, “the awkwardness of your position is grace itself compared with that of a man engaged in the act of cutting off his own head.”

“I’m afraid,” said Pish-Tush, “that unless you can find a substitute——”

“A substitute!” exclaimed Koko. “The very thing! Thank you very much, Pish-Tush. Pooh Bah, I appoint you Lord High Substitute.”

Pooh Bah pondered thoughtfully for half a minute. He was strongly tempted to accept this new and distinguished office, but his better nature prevailed.

“I should like it above all things,” replied Pooh Bah. “Such an appointment would realize my fondest dreams. But no—at any sacrifice I must set bounds to my insatiable ambition!”

And he expressed his views in the following song:

I am so proud,

If I allowed

My family pride

To be my guide,

I’d volunteer

To quit this sphere

Instead of you

In a minute or two;

And so

Although,

As of course you know,

I greatly pine

To brightly shine*

And take the line

Of a hero fine,

With grief condign

I must decline

To sit in solemn silence in a dull dark dock

In a pestilential prison with a life-long lock,

Awaiting the sensation of a short sharp shock

From a cheap and chippy chopper on a big black block!

Having thus expressed his views, Pooh Bah hastily retired (lest, if he remained, he should allow himself to be over-persuaded), followed by his faithful subordinate.

Koko was in a terrible state of mind.

“Here,” said he, “am I who allowed myself to be respited at the last moment, simply in order to benefit my native town, and it is now suggested by a man whom I have laden with honours, that I should consent to die within a month! Is this public gratitude? Is this——”

At this moment Nanki Poo appeared, with a rope in which he was making a large noose.

“How dare you interrupt?” said Koko. “Am I never to be permitted to soliloquize?”

Koko was fond of soliloquizing because his medical attendant said that contradiction was bad for him as it flew to his head, and Koko could rely upon it that while he was speaking to himself, nobody could contradict him.

“Go on,” said Nanki Poo. “Don’t mind me.”

“What are you going to do with that rope?” asked Koko.

“I am about,” said Nanki Poo, “to terminate an unendurable existence.”

“No, no, don’t do that,” exclaimed Koko, who was really a humane man. “This is horrible! Why, you wicked, wicked man, are you aware that in taking your life you are committing a crime at which society revolts—a crime of the most disgraceful and inhuman character which—which——”

And Koko paused for a moment, for a most ingenious idea had just occurred to him.

“Well?” said Nanki Poo, “ ‘a crime of the most disgraceful and inhuman character.’ Go on.”

And Koko, trembling in every limb at the bare thought of the proposal that he was about to make, whispered:

“Is it absolutely certain that you are resolved to die?”

“Absolutely,” said Nanki Poo, attaching the rope to a bough of a tree.

“Will nothing shake your resolution?”

“Nothing!”

“Threats, entreaties, prayers—all useless?”

“Quite. My mind is made up.”

“Then,” said Koko, “if you really mean what you say, and if nothing whatever will shake your determination, don’t spoil yourself by committing suicide, but be beheaded handsomely at the hands of the Public Executioner.”

“I don’t see how that would help me,” said Nanki Poo.

“You don’t?” replied Koko. “Observe. You’ll have a month to live and you’ll live like a fighting-cock at my expense. When the day arrives there’ll be a grand public ceremonial—you’ll be the central figure—no one will even attempt to deprive you of that distinction. There’ll be a procession, bands, Dead March, bells tolling, all the girls in tears, Yum-Yum distracted—then, when it’s all over, general rejoicings and a display of fireworks in the evening! You won’t see them, but they’ll be there all the same.”

Nanki Poo was touched by the thought that Yum-Yum would mourn for him.

“Do you think,” said he, “that Yum-Yum would really be distracted?”

“I’m convinced of it. Bless you, she’s the most tender-hearted little creature alive.”

“I should be sorry to cause her pain,” replied Nanki Poo. “Perhaps after all, if I were to travel in Europe for a couple of years, I might contrive to forget her.”

“Oh, I don’t think you could do that,” said Koko hastily. “Life without Yum-Yum—why it seems absurd!”

“I’ll tell you how we’ll manage it,” replied Nanki Poo. “Let me marry Yum-Yum to-morrow and in a month you may behead me.”

“No, no,” said Koko, “I draw the line at Yum-Yum.”

“Very good,” said Nanki Poo. “If you can draw the line, so can I.”

And he proceeded to illustrate his meaning by slipping the noose over his head.

“Stop! Stop!” exclaimed Koko, terrified lest he should carry out his threat. “How can I consent to your marrying Yum-Yum when I’m engaged to marry her myself?”

“She’ll be a widow in a month,” replied Nanki Poo, “and you can marry her then.”

“That’s true, of course,” said Koko; “but, dear me—my position during the next month will be most unpleasant.”

“Not nearly so unpleasant as my position at the end of it,” replied Nanki Poo.

“Well,” said Koko, “I agree. I reluctantly agree. After all it’s only putting off my wedding for a few weeks.”

“That’s all!” said Nanki Poo.

“But you won’t prejudice her against me, will you? You see I’ve educated her to be my wife and I’ve taught her to believe that I am a good and wise man. Now I shouldn’t like her views on that point disturbed.”

“Trust me,” said Nanki Poo, “she shall never know the truth from me.”

“Treat her well,” continued Koko. “She likes a poached egg for breakfast, half a dozen oysters for lunch, and some warm barley water with a rusk at night. She has, also, a girlish fondness for hardbake.”

“She shall have them all,” said Nanki Poo.

“Then that’s settled,” replied Koko, who, nevertheless, was not at all pleased with his bargain. But some people are never satisfied.

|

“To brightly shine.” This is called a “split infinitive” and is never used by well-educated people. But some allowance should be made for a gentleman who is extemporizing beautiful poetry. |

ow this is a most important

chapter.

ow this is a most important

chapter.

Pooh Bah and his faithful attendant, Pish-Tush, lost no time in making known the serious news, that the Mikado had announced that someone must be beheaded within a month or Titipu would be reduced to the rank of a village. As nearly all the inhabitants possessed property in Titipu to a greater or less extent, they were all keenly interested in the prosperity of the city, which would be hopelessly ruined if it were deprived of its Municipal privileges. Moreover the province of Toki-Saki, of which it was the capital, would be forfeited to the Mikado as a district which had no seat of government from which it could be controlled. Altogether, it was a very serious state of things, and so, as soon as Koko had come to a more or less satisfactory understanding with Nanki Poo, he summoned all the principal inhabitants to meet him in the Market Place at ten o’clock the next day, that he might relieve their minds by telling them what he proposed to do.

At the appointed hour, when all the inhabitants had assembled except the newly-born babies and persons over ninety years of age who were left to take care of them, Koko mounted a kind of pulpit in which the auctioneer who sold cattle usually stood. He was received with the following chorus:

What are you going to do, good sir,

Come tell us quickly pray—

The programme rests with you, good sir,

And must be settled to-day.

Are you going to cut off your head, good sir,

Or does anyone, right away,

Consent to be killed in your stead, good sir?

Come tell us quickly, pray.

Then Pooh Bah exclaimed:

To ask you what you mean to do we punctually appear.

And Koko, unwilling to keep them for a moment in unnecessary suspense, replied:

Congratulate me, gentlemen, I’ve found a volunteer!

To which the crowd, greatly relieved, shouted with one voice the Japanese equivalent for

Hear, hear, hear!

Then Koko led Nanki Poo forward and introduced him to the populace, exclaiming:

’Tis Nanki Poo

I think will do?

He yields his life if I’ll Yum-Yum surrender;

Now I adore that girl with passion tender,

And could not yield her with a ready will

If I did not

Adore myself with passion tenderer still!

Then they all shouted:

How sad his lot,

He loves himself with passion tenderer still!

Thereupon Koko handed Yum-Yum to Nanki Poo. They embraced rapturously, and Pooh Bah, who among many other things was Lord High Toast Master, addressed Nanki Poo in the following tasteful lines:

As in a month you’ve got to die

If Koko tells us true,

’Twere empty compliment to cry

“Long life to Nanki Poo!”

But as till this day month you’ll live

As fellow citizen,

This toast with three times three we’ll give—

“Long life to you—till then!”

May all good fortune prosper you,

May you have health and riches too,

May you succeed in all you do—

Long life to you—till then!

The people took up the refrain of the toast (that is to say, the last four lines) and shouted them with all their might and main. To express the joy with which they heard the good news, they instantly broke into a wild dance, but as the figures had not been arranged and practised, each danced the dance he knew best, and consequently there was a good deal of bumping against each other and tumbling down, but they meant well.

Among the crowd was one mysteriously veiled lady who listened quietly to all that went on, but was conspicuous from the fact that she alone took no part in the rejoicings. She was a good deal knocked about during the wild dance that I have described, and when she had had enough (which was very soon) she threw off her veil and exclaimed:

Your revels cease—assist me all of you!

I claim my perjured lover, Nanki Poo!

The mysterious lady was no other than the plain and elderly Kati-sha, the lady to whom Nanki Poo (as we may still call him) had paid some innocent attentions and whom his arbitrary and dictatorial father, the Mikado, had ordered him to marry on pain of instant death if he declined to do so! With the assistance of a strong and capable band of private detectives she had traced him diligently through his complicated wanderings until she tracked him down to Titipu, where she arrived just as his marriage to Yum-Yum had been satisfactorily arranged. It was most awkward for everybody, and everybody wondered what would happen next. Nanki Poo looked particularly foolish.

Kati-sha prided herself, not without reason, upon her powers of unpleasant declamation. As soon as she had enjoyed the confusion and dismay that followed her startling announcement, she advanced to Nanki Poo and addressed him in these scornful terms:

Oh fool, that fleest

My hallowed joys!

Oh blind, that seest

No equipoise!*

Oh rash, that judgest

From half the whole!

Oh base, that judgest

Love’s lightest dole!

Thy heart unbind,

Oh fool, oh blind!

Give me my place,

Oh rash, oh base!

Having completely withered Nanki Poo with these pleasant little remarks, she next turned her attention to poor trembling little Yum-Yum, and proceeded to give her a bit of her mind

Pink cheek that rulest

Where Wisdom serves!

Bright eye that foolest

Steel-tempered nerves!

Rose-lip that scornest

Lore-laden years!

Sweet tongue that warnest

Who rightly hears.

Thy doom is nigh,

Pink cheek, bright eye!

Thy knell is rung,

Rose-lip, sweet tongue.

“I CLAIM MY PERJURED LOVER, NANKI POO”

This was too bad of Kati-sha. In the first place, she ought to have remembered that, after all, it was no fault of Yum-Yum’s, and, in the second, that in addressing an inexperienced girl, fresh from school, she ought to express herself in simple terms, if she wished her meaning to be understood.

Pink cheek that rulest

Where wisdom serves.

I suppose she meant that she, Kati-sha, was the embodiment of Wisdom, but I don’t see how she “served” except as an example to be avoided. But she was in a tearing rage at the time, and I suppose that this must be taken into consideration in criticising her remarks.

Now Pitti-Sing and her school-fellows had come all, the way to Titipu to act as bridesmaids at Yum-Yum’s wedding, and although Yum-Yum was not going to be married to Koko (just yet) still she was going to be married, and they did not intend to allow their fun to be stopped for any elderly lady, however important she might think herself. So, having plenty of assurance of a modest description, Pitti-Sing went up to Kati-sha (who was trying to remember whether she had said anything unladylike in her rage), and addressed her as follows:

Away, nor prosecute your quest.

From our intention well expressed

You cannot turn us.

The state of your connubial views

Towards the person you accuse

Does not concern us!

For he’s going to marry Yum-Yum—Yum-Yum!

Your anger pray bury

For all will be merry,

I think you had better succumb—cumb-cumb,

And join our expressions of glee.

On this subject I pray you be dumb—dumb—dumb;

You’ll find there are many

Who’d wed for a penny,†

The word for your guidance is “mum—mum—mum”;

There’s lots of good fish in the sea!

And all the other bridesmaids took up the chorus:

The word for your guidance is “mum—mum—mum”;

There’s lots of good fish in the sea!

All this was very bad taste on Pitti-Sing’s part, and I don’t see how her conduct is to be defended. It is most unbecoming for a mere school-girl to address an elderly lady, however plain, in words of ridicule and contempt. She might have expressed her meaning in becoming terms without in any way weakening its effect.

Kati-sha, who was too proud to take notice of the impertinence of a mere chit of a school-girl, directed her next remark to Nanki Poo, who looked as foolish as a young man could look at this public and unexpected claim upon his affections. He and Yum-Yum knelt at her feet to implore her forgiveness, but in vain. She exclaimed:

Oh, faithless one, this insult you shall rue!

In vain for mercy on your knees you sue—

I’ll tear the mask from your disguising,

Prepare yourselves for news surprising—

(addressing the crowd)

No minstrel he, despite bravado!

He is the son of your——

Now an ingenious idea had occurred to Yum-Yum. She had anticipated the probability that Kati-sha would endeavour to frustrate Koko’s intentions to let Yum-Yum marry Nanki Poo, by revealing the fact that he was the son of their monarch, and she had arranged with her school-fellows that if Kati-sha attempted anything of the kind they would drown her voice by making just such a clattering uproar as you might expect from three dozen school-girls all talking at once at the top of their voices. So when Kati-sha uttered the words:

No minstrel he, despite bravado!

He is the son of your——

they all shouted the last words of a humorous song that had been sung by them at their breaking-up.

O ni! bikkuri shakkuri to!

O sa, bikkuri shakkuri to!

Kati-sha, who detected their intention, replied:

In vain you interrupt with this tornado!

He is the only son of your——

and again the girls shouted:

O ni, bikkuri shakkuri to!

O sa, bikkuri shakkuri to!

But Kati-sha was not to be put down by clamour. She resumed:

You little jades, I’ll spoil——

By this time the crowd had entered into the fun of the thing, and two thousand voices shouted:

O ni! bikkuri shakkuri to!

Kati-sha continued:

——your gay gambado—

He is the eldest son——

Again the crowd shouted:

O ni! bikkuri shakkuri to!

Kati-sha again tried to get a word in:

——of your——

Once more the crowd yelled:

O ni! bikkuri shakkuri to!

and at the same time Koko’s brass band played the National Anthem in double time, and in all the keys from A to G.

Kati-sha was exhausted, and moreover she saw that there was not the remotest chance of making her meaning clear to them,‡ so she resolved that she would hasten at once to the Mikado and explain her wrongs to one who was so much more patient than his subjects that he never was known to interrupt a lady who had a grievance to lay before him, however elderly and plain she might be. But before going she fired this parting shot:

Ye torrents roar,

Ye tempests howl,

Your wrath outpour

With angry growl,

Do ye your worst—my vengeance-call

Shall rise triumphant over all!

Prepare for woe,

Ye haughty lords!

At once I go

Mikado-wards.

And when he learns his son is found

My wrongs with vengeance will be crowned!

But as she uttered the last lines the crowd again shouted:

O ni! bikkuri shakkuri to!

and poor Kati-sha had to give it up as a bad job and hurry off as fast as possible to explain the situation to her revered monarch.

|

I fancy that she meant by this that Nanki Poo was so short-sighted as not to perceive that her moral and social qualities were an adequate compensation for the drawbacks of advanced age and damaged personal appearance. But when people lapse into poetry you never can be quite sure what they mean. |

|

Cheap, considering all things. |

|

I should have thought that as it was quite clear that the “missing word” rhymed with “bravado,” “tornado,” and “gambado,” the crowd might have guessed that it was “Mikado.” But people who are quite intelligent as individuals are sometimes extraordinarily dense when they are acting in a mob. This is the only way in which I can explain it. |

he very next day Yum-Yum was to be

married to Nanki Poo. Their wedded

life was only to last a month (for at the

end of that time Nanki Poo was to be

beheaded), but it was going to be such

a happy month that the close of it

seemed to be an immensely long way off and consequently

hardly worth considering. That is the way

with young and foolish people who live only for the

present and think it is time enough to consider how

they will deal with a day of difficulty when that day

arrives.

he very next day Yum-Yum was to be

married to Nanki Poo. Their wedded

life was only to last a month (for at the

end of that time Nanki Poo was to be

beheaded), but it was going to be such

a happy month that the close of it

seemed to be an immensely long way off and consequently

hardly worth considering. That is the way

with young and foolish people who live only for the

present and think it is time enough to consider how

they will deal with a day of difficulty when that day

arrives.

That morning Yum-Yum was occupied a long time at her toilette. She naturally wanted to look to the best advantage, but as her three dozen bridesmaids had come to help her to do her hair, and as each bridesmaid had her own idea as to how hair should be done, and moreover as each in succession undid what her immediate predecessor had done and did it again in her own way, the process became rather tiresome. Eventually, however, Yum-Yum, whose policy it was to conciliate everyone, allowed each bridesmaid to do a little bit, so the result bore the same relation to an ordinary head of hair that a fruit salad does to each of the individual delicacies of which it is compounded. Then it became necessary to touch up Yum-Yum’s cheeks and lips with a little colour, for Japanese young ladies consider this to be quite correct, although English ladies would rather look as yellow as frogs than consent to do anything so shocking.

As the bridesmaids titivated Yum-Yum’s head and face they sang the following appropriate verses:

Braid the raven hair,

Weave the supple tress,

Deck the maiden fair

In her loveliness.

Paint the pretty face,

Dye the coral lip,

Emphasize the grace

Of her ladyship!

Art and nature thus allied

Go to make a pretty bride.

Then Pitti-Sing proceeded to give her a bit of advice, founded upon what would have been her experience if she had had any:

By the time they had finished their singing, Yum-Yum’s toilet was completed, and all the bridesmaids withdrew to their respective apartments with the view of putting a few finishing touches to their own impudent little faces, except Pitti-Sing and Peep Bo, who shared Yum-Yum’s rooms.