* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Jerry Todd--Caveman

Date of first publication: 1932

Author: Edward Edson Lee

Date first posted: Nov. 13, 2016

Date last updated: Nov. 13, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20161114

This eBook was produced by: Dave Morgan, Stephen Hutcheson & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

By

LEO EDWARDS

Author of

THE JERRY TODD BOOKS

THE POPPY OTT BOOKS

THE ANDY BLAKE BOOKS

ILLUSTRATED BY

BERT SALG

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1932, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP, Inc.

Made in the United States of America

He has big eyes, pleasing ways and three older sisters who inspect his ears each morning and in various ways take it upon themselves to see that he grows up in exactly the way that a neat younger brother should grow up. He’s a fine lad. And because he is my pal as well I’m going to include him in the somewhat select group to which various books of mine have been dedicated. So here you are,

BILL SCHAEFER

(old sock-in-the-wash)

of Madison, Wisconsin. May you live long and daily grow longer.

Whenever I complete a new book I like to feel that it is going out into the world to provide wholesome entertainment for boys and girls and also add materially to my wide circle of young friends.

I try to put that friendly something into my books that will make the young readers want to write to me. I’ve always done that. So it isn’t surprising that years ago, when I had but a few titles, boys and girls began writing to me, wanting me to know how dear my books were to them.

Now I receive thousands of letters yearly. And I have someone to help me handle these letters, as it would be impossible for me to answer each and every letter myself and write books at the same time.

All of the letters from old-timers, all of the important letters from new fans, all of the letters containing questions about the characters in my books, all of the letters asking personal advice, all of the letters containing poems, in fact, all of the letters of any importance whatsoever are turned over to me for attention. And I answer as many as I can. I’m sorry I can’t answer them all.

And then, when these letters have been answered, I put them aside for use in a later “Chatter-Box,” a department appearing in all of my books, in which I keep in personal touch with all of my young readers.

This is your department, boys and girls. To be represented, write me an outstanding letter; or send in a poem. If your poem is published you will receive a free autographed copy of the book in which the poem appears. We have sent out hundreds of autographed books and expect to send out hundreds more. The poems printed in this “Chatter-Box” will give you an idea of the kind we prefer.

And now let us dig into this big pile of letters and see what some of the Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott fans have to say.

“I have read all of your books, and ‘swell’ goes for every one—and how!” writes Chris Morley, Jr., Roslyn Heights, Long Island, N. Y., in applying for membership in our Freckled Goldfish club. “I am a Jerry and Poppy fan if there ever was one. I’m thirteen years old, which is the best age to be. When I read about Jerry in his Bob-Tailed Elephant book I thought of a plan. Being interested in marionettes I have given several small performances with some puppets. My plan is to make puppet copies of Jerry, Poppy and their friends and try out some of their dandy adventures. I think it’s a swell idea. Don’t you?”

Yes, sir, that is a grand and glorious idea. If I get time next summer I’m going to do it myself. If any of you fellows are interested, write to Chris at the address given.

And by the way, we’re publishing complete addresses of all contributors so that the boys and girls interested in this department can write to one another.

Freckled Goldfish Howard Conley of 3309 Lansmere Rd., Cleveland, Ohio, writes to tell me how well he likes the Trigger Berg books. Howard makes the suggestion that we give the Sally Ann (Jerry’s old boat) a new motor. Now that the boys have a new boat I hadn’t thought much about the old Sally Ann, which played such an important part in the “Oak Island Treasure” and “Whispering Cave” books. But we may resurrect the old scow some time. And who knows but what we may give it a new motor, exactly as Howard has suggested. He concludes with the following:

“You sure have a swell reputation among the women as I heard my mom and a lady friend say that you must be a swell man to know.”

Ahem! Maybe I hadn’t better tell my wife about that.

“I have read thirteen Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott books and still think they are the best books I ever read,” writes Freckled Goldfish Edward Mackey, 3421 So. Oakley Ave., Chicago, Ill. “The book, The Talking Frog, was read over by me more than five times. It was my first book I read of your series. I have at least ten boys interested in your books. Whenever I get a new title I let them read it. My hobby is sports. I particularly like baseball. Did the Strickers find the second cave in Whispering Cave? In the Tittering Totem did Jerry give Mr. Hoenoddle the engine that Mr. Corbin invented?”

Glad to hear from you, Ed. And hope that you’ll continue to find much pleasure in my books. The Strickers didn’t find the inner cave in the Whispering Cave book. But they did get into the cave in Jerry Todd, Pirate. Mr. Corbin invented a carburetor, which Poppy tried out on a borrowed motor. This motor belonged to Art Davidson; and naturally the motor was returned to Art.

Having read my Purring Egg book, Bernard R. Feick, 5947 Chester Ave., Philadelphia, Pa., played a somewhat similar joke (the joke was on Jerry in the Egg book) on a small neighborhood boy who had a collection of turtles.

“One day,” reports Bernard, “a small white egg was found in the turtle pen. But the egg was damaged before the young owner found it. This happened a second time. Then my chum and I concocted a scheme—we took a small wooden egg of the same size from a magic set and put it in with the turtles. Soon Junior glanced in the pen. Another egg! Whoopee! He proudly showed the wooden egg all over the neighborhood. And then, alas, he learned the truth about it.”

David Schulhen, 3112 Portis Ave., St. Louis, Mo., wants to know what would happen if a Freckled Goldfish got the measles. I’m wondering myself. Also Dave tells me about his new American Boy subscription.

“I used to read old cheap magazines,” writes Dave. “But now I read the American Boy. It sure is the horse’s heels.”

Did you know, Dave, that the American Boy serialized five of my books, Andy Blake, Whispering Mummy, Rose-Colored Cat, Waltzing Hen and Purring Egg?

“If the Jerry Todd books aren’t the best books I’ve read (and I’ve read quite a few) I’ll eat my Sunday pants. And why are these books so interesting? The way you write them, just as if you were a boy yourself, and the little sayings and everything. I’m not a member of the Freckled Goldfish club, but want to join. Also I’m sending stamps for a ritual so that I can organize a club in my own neighborhood.”

Donald Goldberg, 1623 East 15th, Tulsa, Okla., is the writer of that letter. And now no doubt he has a thriving Freckled Goldfish club of his own, like so many other boys of his age.

Julia Ann Ryan, 3805 Jackson Ave., El Paso, Texas, writes at length to inquire if girls may join the Freckled Goldfish club. And the answer is, sure thing. In fact girls are at the head of some of our most successful branch clubs.

“I started reading your books about three years ago,” writes Julia Ann. “I borrowed the first four books from a boy living near me. I sure did like the books, so bought more. Two years ago a girl friend of mine brought the Galloping Snail to school. I read it and thought I would die laughing when Jerry and Poppy were trying to start the old car. A friend of mine didn’t care much about reading. But I got her started on the Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott books. I thought she wouldn’t stop until her eyes fell out, but they’re still in. My friends and I all talk Jerry’s ‘lingo.’”

“Please send me a Freckled Goldfish card as fast as you can,” writes Robert Leibourtz, 2307 Ave. M, Brooklyn, N. Y. “One time I was reading the Oak Island Treasure in school and snickered so loud that the teacher told me to shut up.”

The next letter was written jointly by Marion Rand and Lyman Carter of Eagle River, Wis., who begin by asking for Freckled Goldfish cards and buttons.

“We have many adventures like Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott,” the boys report. “Today we went into a spooky barn. A man was walking around in the barn and heard us. He was so scared he ran away. We play that we are Juvenile Jupiter Detectives.”

“At our school,” writes Freckled Goldfish Robert Rolley, 2906 58th Ave., Oakland, California, “we have a small paper and I had a whole page last time. The page was for Jerry Todd and the Whispering Mummy. The next time I’m going to have a second page on which I’ll advertise your books. Please send me a description of the Andy Blake books.”

Many thanks, Bob, for your mention of the Mummy book in your school paper. I like to see boys interest their comrades in my books, for that spreads the fun.

Andy Blake is a young man. So naturally his adventures are more grown-up in character. Still, he comes in contact with a number of younger boys, particularly in Pot of Gold, which I think is one of my best books. I’m trying hard to make these stories of interest to small boys as well as older ones. Try the Pot of Gold, Bob, and see how you like it.

Roy Atkinson, 6323 N. Paulina St., Chicago, Ill., gives a very interesting account of a secret room that he and his brothers built in their home. Also a drawing accompanies the letter, giving the location of the secret chamber.

“We once had a big store room,” writes Roy. “But a carpenter changed this so that the store room became a small closet instead. This left a lot of space behind the closet. Then along comes clever little me with a saw. Presto! In no time at all we had a secret door in one of the closet walls. And didn’t we have fun after that! Oh, baby! We kept the secret for five months. Then, my brother having left the light on in there, the secret got out. What happened to Henny Bibbler in Editor-in-Grief? And why not have a Juvenile Jupiter Detective organization? My father is night editor of the Chicago Tribune.”

Henny’s all right, Roy. He and Jerry often get together, but I hardly felt it was necessary to include Henny in the Grief story. And some day we may have a nation-wide Juvenile Jupiter Detective organization, as you have suggested. Other fans have made the same suggestion.

“I am twelve years old and live in St. Petersburg, Florida, at 919 9th Ave. S.,” writes Henry Baynard, who further states that he met me when I read to the St. Petersburg children one Saturday morning in the public library. “I am very fond of your books. Won’t you please, in your next book, write about the gang having fun on motor cycles? I love motor cycles, and hope some day to have one of my own. Then maybe I’ll ride up to Wisconsin to see you!”

Henry further submits an outline for such a book as he suggests. He has called his story The Wonderful Gift. And I wish I could publish his outline complete, for it is very interesting; and you can bet your Sunday shirt that when I next go to St. Petersburg to spend the winter I’ll look him up, and add him to my big circle of boy pals down there. Briefly, the story starts with Jerry eating cookies in his home. The telephone rings; and Jerry learns that there is a big crate for him at the freight depot. Also Poppy has a similar crate. So Jerry and Poppy head for the freight depot, fighting the Strickers on the way with rotten eggs. The crates each contain a brand new motor cycle, the gift of Art Davidson, one of the chief characters in Tittering Totem. And so the tale runs on.

But let us drop the letters temporarily and read a few poems.

A few weeks ago I introduced a new series of books featuring dogs and other animals with Tuffy Bean, a skylarking “purp” in the leading rôle. Though written for smaller children, these books are proving very popular with the older fans. In fact, here’s a poem from a twelve-year-old Freckled Goldfish, Tom Mingey, 44 Fairview Ave., Lansdowne, Pa., in which special tribute is paid to Tuffy.

Tribute to Tuffy

Can’t anybody give Tuffy a break?

It’s time he got it, too.

What do you think of his books?

Be like me and say he’s “true-blue.”

You don’t hear much about Tuffy,

It’s all Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott.

Give the little dog his due

And write about him a lot.

Tuffy Bean certainly is swell,

The way he catches those crooks.

And believe me, fellows, more than me will say,

“Thar’s fun in them thar books.”

Thanks, Tom. For years I’ve been wanting to write a series of books about a dog. I’ve always had dogs around me, and having given them and their kind a great deal of study, I felt that I could create dog stories of considerable interest. And now the new series has been launched, with three initial titles, Tuffy Bean’s Puppy Days, Tuffy Bean’s One-Ring Circus and Tuffy Bean at Funny-Bone Farm. These will be followed shortly by Tuffy Bean and the Lost Fortune, and then Tuffy Bean’s Hunting Days. While Tuffy is the chief character, and tells the story himself, in the same manner that Jerry Todd tells his stories, the new books are full of interesting characters, including Tuffy’s masters, his friends and the boys and girls with whom he comes in contact. These are stories of children and adults, told from a dog’s viewpoint, and some splendid humor develops. I really feel that these new books are the best thing I have done. So, as I say, Tom, I’m very grateful to you for your tribute to Tuffy. He’s my “baby.” And I love him dearly.

Having mailed Tom an autographed copy of this book, another will be wrapped up for Freckled Goldfish Fred Haubold, 1816 N. Karlov, Chicago, Ill., who displays his poetical talents as follows:

Seven-League Stilts

Poppy Ott and Jerry Todd

Were good friends, though sort of odd.

Poppy was an advertiser;

Jerry was his chief adviser.

“Into the stilt business we will go,”

Said Poppy, with a kind of show.

“Our stilts will be a big surprise

For business men who advertise.”

Jerry said: “You must be crazy.”

But Poppy said: “Oh, don’t be lazy.

This afternoon we’ll get an order,

Even though we must go to the border.”

Then to Ashton they did go,

Their wonderful stilts to merchants to show.

They went to the store of Heckleberry,

Who had a nose as red as a cherry.

Poppy explained he had a trade booster,

But Heckleberry got red as a rooster.

He ordered them to get out quick,

Or else he’d chase ’em with a stick.

Then they went over to Mr. Kelly,

Who looked as though he liked jelly.

He greeted them with a kindly smile,

And listened to them all the while.

Poppy spilled his selling lingo,

And Jerry’s eyes almost went bingo.

Mr. Kelly said: “That’s fine!

Bring the stilts to-morrow at nine.”

Uncle Donner went to the cemetery,

His only will (they thought) to bury.

If you want to find out if Crook Donner wilts,

Read “Poppy Ott’s Seven-League Stilts.”

Well, well, well! And here’s another poem about Tuffy. Evidently the “gang” likes him as well as I do. And by the way, did you know that Bert Salg has drawn almost thirty pictures for each of these new books? Pictures in each chapter! And what pictures! But let’s get to this poem, written by Walter Frisbie, Jr., 188 Lawrence St., New Haven, Conn.

Tuffy’s Golden Dream

“Oh, goodness me,” said Tuffy Bean,

“What is this that I see?

It looks to me like robbers.

I wonder can it be.”

“I wish it looked like dinner,”

Said little Cobby Bean.

“For if it looked like dinner

I’d be just mighty keen.”

“But look!” said little Tuffy.

“They’ve gone up to the cave.

Now we must hide and watch them

And be very very brave.

“Now listen, Cobby, what they say,

’Tis ‘open sesame!’

And look! The door comes open wide!

They’ve put bags in there. See?

“Now off they go way down the hill,

We’ll go up quickly now.

We must get that door open,

But I don’t know just how.”

So then Tuffy and Cobby

Got up and went to see

If they could open up the door

By saying “sesame.”

But being little puppies,

Of course they couldn’t talk.

The only thing that they could do

Was just to growl and bark.

They found a rope and pulled it hard,

It opened up the door.

And there they saw big bags of gold,

All piled upon the floor.

“Let’s get it quick and take it home,

The mortgage it will pay.”

“Oh, yes, let’s go,” said Cobby.

“We must go right away.”

They carried all the nuggets home,

It was hard work, not fun.

They worked and worked and never stopped

Till all the work was done.

But Mrs. Bean was not so pleased,

She wasn’t pleased at all.

There was a trick about the gold.

’Twas very tragical!

So Tuffy Bean and Cobby

Gave up their quest for gold

And lived like other little dogs,

At least so I’ve been told.

Gee-miny crickets! And here’s still another one about Tuffy, written by Bob Allgeier, 203 Oakland Ave., Mountain Grove, Missouri.

Tuffy

There is a dog named Tuffy Bean,

A nicer dog I ne’er have seen.

Cobby Bean is his brother,

In the cave they nearly smother

When Bouncing Bella released her stink,

The dogs ran out as quick as a wink,

Found a swell bottle of liniment,

And with it made the skunk repent.

That’s Tuffy!

Tuffy and Cobby let out warbles

When they found the golden marbles,

Thinking they were solid gold

And for many dollars could be sold.

Old man Popover, the dirty thief!

In this book did come to grief.

Moonlit statues are in the scenery

Looking down upon the creamery

So’d Tuffy!

Our next poem was written by Bob McCaleb, Covington, Va. It’s his statement that he read one of my early books in the American Boy, and he has some very pleasing things to say about my books as a whole. He collects autographed books, he tells me, so the book that is on its way to him will come in handy. Here’s his poem:

I’ve read of a boy named Jerry Todd,

And did he make Bid Stricker hit the sod!

Oh, man!

Scoop, Red and Peg are his bosom chums,

And they don’t sit around and suck their thumbs.

Oh, no!

Jerry and his pals are always on the go.

Sometimes in the Tutter canal they’ll take a row,

And again when the weather is hot

With their bathing suits on in the water they’ll sot.

This next poem, written by Norman Salshutz, 70 Hill St., Brooklyn, N. Y., is of a different type.

Old King Cole

Old King Cole was a merry old soul,

He washed his face in a broken bowl,

He combed his hair with a rocking chair,

Then went into the street for some fresh air.

He came in for breakfast at half-past eight,

He washed his soup and he drank his plate,

He drank his bread and he ate his milk,

And then put on his woolen cloak of silk.

He went out again at half-past ten,

Taking his umbrella and his little pen.

It started to rain cows and hogs,

And old King Cole was left in the fogs.

At last he reached home as tired as could be,

As cold as a hot-dog, as wet as a sea.

He went to lay down on his nice clean bed,

But laid himself down on the umbrella instead.

John F. Sears, 69 Grant Ave., White Plains, N. Y., is the author of the next one.

Chums

Jerry Todd and Poppy Ott

Are good detectives when they get hot.

But they are not the only ones—

There’s Trigger Berg and all his chums.

I will mention them to you,

There’s Tail Light, Slats and Friday, too.

Here’s good advice for you and me,

Read Trigger Berg and the Treasure Tree.

Accompanying the next poem is a fine long letter from Bob Rubin, 5821 Larchwood Ave., Philadelphia, Pa. The letter would interest you, for Bob’s a clear-headed purposeful boy. But we have space for only the poem. Here it is:

The Battle of the Ages

This is the story of a battle of renown,

Which took place in the canal near Tutter town,

Between our heroes, the five pirates bold,

And the Strickers, the five’s enemy of old.

The Strickers had raised from the canal, we know not how,

Something that belonged to the pirates, namely their scow,

Which four of the five used in many cases

To do many deeds and to go many places.

The fight began because the Strickers haughtily laughed

When they saw the five pirates sailing their raft,

Which they constructed to aid in lowering the enemy’s conceit

By recapturing the scow and forcing a retreat.

Our friends, who were clad in pirate attire,

Had mounted on their raft the inner tube of a tire.

This they used for their cannon, and for balls wads of clay,

While the enemy used pebbles in a heartless way.

But soon, with the majestic help of “slightly used” eggs

The Strickers were sent home with their “tails between their legs.”

Our friends, together with the scow, came unharmed from the fray.

Thus ended an exciting and eventful summer day.

Wow! I just got through reading a six-page letter. And pasted on the last page is a picture of the writer, Freckled Goldfish Harry James, 307 Brown St., Union City, N. J. It certainly is a peachy letter. Harry has traveled from California to New York, and tells me (ahem!) that nowhere in his travels has he found (ahem again!) the equal to our Jerry Todd books. Now, after that I just had to publish his poem. Here it is:

In a little town in Illinois

There lives six happy dandy boys,

They are the kind you like to meet,

And never show off on the street.

The first is Jerry Todd,

A fellow as fine as can be,

And though it may seem odd,

He’s the one boy I’d dearly love to see.

The second is Howard Ellery,

Whose nickname is Scoop.

And when the Strickers get too fresh

He knocks them for a loop.

Then third comes Red Meyers,

Who of eating never tires.

Though he’s a freckled runt with red hair,

When it comes to being loyal he’s all there.

The fourth is Peg Shaw,

A boy as strong as an ox.

And it sure makes you hee-haw!

When the Strickers he does “box.”

Fifth in the gang comes Rory Ringer,

From Hengland across the sea.

And ’e sure is a little ’umdinger,

For ’e’s fine as ’e can be.

Now Jerry’s friend is Poppy Ott,

And I’ll say I sure like him a lot.

He’s a wonderful mind, and uses it, too.

In fact there’s hardly a thing he can’t do.

Robert Frisch, 2608 Humboldt Ave. So., Minneapolis, Minn., tells about a school friend who dramatized Jerry Todd and the Whispering Mummy. After that every boy in the room wanted to borrow the book. Here’s a short poem that Robert wrote:

Jerry Todd

Jerry Todd, it is he,

Who writes those books so full of glee.

I bought the series one by one,

A lot of mystery and full of fun.

I hope Jerry will write more,

As I say, fun and mystery galore.

Use all the paper that you can

And have a copy for each little fan.

From J. R. Ferguson, Box 22, Stephenville, Texas, comes this one:

Did you ever hear of a frog that could talk?—

Or a puzzle room where ghosts would walk?

Jerry Todd had an adventure like this.

It is a book you will not want to miss.

Jerry helps a boy save an invention

And tries to solve the inventor’s intention.

What is meant by ten and ten?

Why was the mill searched time and again?

Mystery, suspense, surprises and fun,

If you want it all get this one:

Jerry Todd and the Talking Frog.

And does that bring me to the bottom of my “poem” pile? Oh, no! But I’ll have to stop, going deeper into the pile next time. In the meantime, why don’t you get busy and write a poem. If you strike an original theme your poem will go on the top of the pile. And your reward will be an autographed copy of the book in which the poem appears.

First, before I tell you something about the many pictures that now come to hand, I want to tell you what Grosset & Dunlap told me. It was to promise boys and girls, who sent me pictures of themselves, that they’d get one of my pictures in return. This was handled in New York. Now we learn that in many cases we sent pictures to fans who already had pictures—that naturally would happen with me handling some of the mail here and the rest of it going out of New York. So I’ve been asked to withdraw my promise, to avoid added confusion. And that’s that. I hope it won’t mean that I’ll get any fewer pictures. For I’m making a mammoth collection of the snapshots sent to me. My own pictures, as mentioned, are of the professional type, very large and quite expensive to handle. They cost Grosset & Dunlap a great deal more than the price asked for them. If you want one, mail ten cents in stamps to Leo Edwards’ Secretary, Grosset & Dunlap, 1140 Broadway, New York, N. Y.

Right on the top of the pile (and believe me it is a pile!) is the picture of a boy in white ducks standing beside an airplane. This is Richard Steinlage, 2550 North Grand Blvd., St. Louis, Mo. Like so many other boys Dick aspires to become a pilot—and here’s hoping that is ambitions are realized. He’s much enthused over the new Tuffy Bean books—in fact he sent me a poem built around Tuffy. But I couldn’t possibly find room for it.

Oh, boy! Here’s another bird all lit up in white ducks. “Red” Claude Helwig is the name, and the address (write it down, girls, for he’s mighty good looking) is 121 Moneta Way, San Francisco, Calif.

Next comes Kenneth Dorman, shown with a big “A” on his sweater. Durham Road, Bronxville, N. Y., is the address. Thanks, Ken. I bet you had a swell time up in Nova Scotia.

And what’s going on here? Five boys, playing marbles; then, in another picture, two boys, and in a third picture a swarm of pigeons—or do pigeons come in herds? I see by the accompanying letter that the pictures were sent in by John McCaslin, 138 Payne St., Riverside, N. J. John thinks I ought to supply Jerry with a dog—which reminds me that I partly promised my young readers that there would be a dog in this story. But I couldn’t bring him in, having nothing for him to do. I’m hoping though that I can give Jerry a dog very soon. In the meantime I have the new Tuffy Bean books for young dog lovers. John has a Goldfish club. That, I take it, explains the group picture. And what a funny look John has on his face in the other picture. I bet he’s a swell little guy, all right.

John Tree of 61 Porterfield Place, Freemont, N. Y., sends two pictures of himself. And here again the white ducks have been brought out for the occasion. After that comes a beach picture of Victor C. Clark, 747 East Polk St., Phoenix, Arizona. In the background is Saltan Sea, Imperial Valley, Calif. And what’s this? Another poem! Well, I certainly can’t pass up this one.

A Boost for Jerry Todd

The books that Leo Edwards writes

Are best for girls and boys,

Be it Ott, Todd, Berg or Blake—

It’ll add much to your joys.

Of all the books I’ve ever read,

Old Jerry takes the cake.

All books, put side of his,

Should be dumped in the lake.

I liked the Whispering Mummy,

That was one spooky tale,

And if you want a real good book

You’ll find that it’s on sale.

And then there comes the Cat book

In which the felines rest.

To get the cats out of the way

The gang sure did its best.

The Treasure of Oak Island

Is equally as funny.

And once the old clay scow was fixed

The boys sure earned the money.

The spooky prowling peril

In the tale of the Waltzing Hen—

Another peachy story

From Leo Edwards’ pen.

I could tell of these swell stories

Forever and a day.

Just read one of the Jerry Todds—

It’s proof of what I say.

A way to spend your money

That’s really swell and nifty

Is, buy a book of Jerry Todd—

A very-well-spent fifty.

Getting back to the pictures, I have two here of Frank Thompson, 172 West St., New Haven, Conn. In the first picture Frank is shown with his father, sister Mary and dog Rex. With him in the second picture are his mother, older brother and little sister. Here too is a poem, but not quite good enough for publication. Better luck next time, Frank. The drawing of the storekeeper who sells you your books is good.

Next we have a picture of a small Goldfish club. The organizer. Bill Ward, is shown in the middle—he sure wrote a swell letter. With him are Peter Cody (R.F.) and Champ Landgren (L.F.). Then comes a picture of George Prestwich, Jr., 104 Strawbridge Ave., Westmont, N. J. And after that a picture of a boy with glasses—it’s George Sanford, 185 Hillside Ave., Hartford, Conn., who, like so many other fans, urges me to supply Jerry with a dog. Believe it or not there’s about 168,942 words in George’s letter—but I read it all and enjoyed every word of it. Here’s a real boy—plays tricks on Hallowe’en, has had several “scraps,” and, to cap the climax, has had an affair of the heart. “I used to speak to her every time I got a chance,” writes George, “but she would tell me to shut up. I didn’t mind that. She had blue eyes and was good looking.”

Poor Berner Kellough of 636 South 20th Ave., Maywood, Ill. His parents bought him a new suit, together with a new hat, and then made him pose for this picture. He tells me, in his letter, that, hating the hat, he threw it away. But it looks O.K. to me. With him in the picture is his pal Arthur.

I wish I had space to tell you about more of the pictures that I have here. But I’ve simply got to leave space for the usual club announcements. So the rest of the pictures will have to carry over till another Chatter-Box is in formation.

When you have read Jerry’s story about the odd floating island that he and Sinbad visited you’ll probably wonder what became of the musical bedbugs. I’m wondering myself! Did Sinbad grab a bottle of these marvelous bedbugs just before the island sank? If so, what became of the bedbugs? There’s a riddle for you. And I’m going to put up ten autographed books for the ten best answers. Mark your letter Bedbug Contest and specify the particular book that you want; otherwise you’ll receive a copy of the book in which your name appears as a prize winner.

Do you belong to this club? It’s easy to become a member. All you have to do is to take one of my books to school, induce he teacher to read it aloud or let you read it aloud, reporting the matter to me, after which your name will be included in the club file. This club has nothing to do with the big Freckled Goldfish club.

The names of all members were published in the “Chatter-Box” in Trigger Berg and the Sacred Pig. Also the names of the prize winners were published. Here’s the general plan: At the end of the first year the names of all club members were put “into the hat” and ten names drawn. Each of these ten boys and girls received an autographed copy of Sacred Pig. At the end of the second year twenty names will be drawn, omitting the names of the earlier prize winners, and at the end of the third year thirty names will be drawn. Here is a fine chance for you to secure a free autographed book. And not only that, but if you take one of your Todd, Ott, Berg, Blake or Bean books to school, and it is read aloud, you’ll provide fun for the whole room. That’s something to think about.

“I had my teacher read one of your books to the class,” reports Margaret Mary Howard, 601 S. Windsor Blvd., Los Angeles, Calif., “and the scholars liked the story so well that the teacher now reads your books entirely.”

“I am a boy twelve years old and have read many of your books,” reports Neal Schenet, 16 S. Chapel St., Elgin, Ill. “When I am gloomy I pick up one of your books and—presto!—there is no more gloom. I just got Poppy Ott and the Prancing Pancake yesterday. My teacher is going to read it to my grade.”

“My teacher read Editor-in-Grief to the class and, boy, did the kids laugh,” reports Billy Howard, 200 Prospect St., Westfield, N. J. “Now the kids all want to borrow my Oak Island Treasure book.”

“My teacher is now reading Trigger Berg and His 700 Mouse Traps,” reports Patrick Perry, 719 W. Hull St., Denison, Texas. “To-day she read the part where Charley Robin tells Trigger and his gang about the lumber camp.”

“I wish to enroll as a member in your School club,” writes George Sentman, 4125 5th Ave., Moline, Ill. “I had a book report on Jerry Todd, Editor-in-Grief. The kids liked it so well that they insisted on having the teacher read it. So I brought it to school. The kids got so crazy over the book that they asked the teacher to read it at recess. And she got so interested in the book herself that she actually did let them stay in at recess while she read to them! The kids bellowed so loud that the principal came tearing in to see what was going on. She too got interested in the book.”

This next letter isn’t from a club member, but it shows what happens when a good fan does take a book to school.

“I first found out about your interesting books,” writes M. Vincent Brockschmidt, Jr., 1039 Wells St., Cincinnati, Ohio, “when a friend of mine brought Poppy Ott and the Stuttering Parrot to school to read to the class. Now I have ten Ott and Todd books.”

“This is to inform you,” reports Burt Cherney, 1234 N. 16th St., Philadelphia, Pa., “that I have fulfilled the requirements of the School club so put my name down on that list of yours. Here’s hoping that I’m one of the lucky ones to get an autographed book.”

“My teacher has read two of your books to the class,” reports Carroll Metzner, 233 Frank Ave., Racine, Wis. “I have all of the Todd, Ott, Berg and Blake books and almost all of the boys in the neighborhood have read them.”

“A month ago,” reports John Dillon, 156 Broad St., San Francisco, Calif., “a boy lent me a book named Poppy Ott and the Freckled Goldfish. I enjoyed it very much and went to see if my favorite book store had it—they had, and now I have all the Ott and Todd books. As soon as another one comes out I will run and get it. I also enjoy your Andy Blake and Trigger Berg books. I read in the books of your Freckled Goldfish club, which I am joining, and also I have the neighborhood boys interested in starting a branch club. I asked my teacher if I could start a club in the class and she said it was all right. So I asked her to read a Poppy Ott book to us and she read Poppy Ott and the Stuttering Parrot.”

“I was tickled pink,” reports Nyman Tripp, Kibbie, Michigan, “when I received my Freckled Goldfish card and button. Our teacher read one of your books to us. It was the Stuttering Parrot book. Having read the Whispering Mummy book I wanted to organize a Juvenile Jupiter Detective club in Kibbie. But we didn’t have any mysteries to solve so we didn’t have any club. I’m going to organize a Freckled Goldfish club, having gotten two members already.”

“I took a Jerry Todd book to school and asked the teacher if she would read it aloud to the class. She said she would. The first book that she is going to read is Jerry Todd and the Talking Frog.” Thus reports Freckled Goldfish Charles Egner, 228 Main St., Emaus, Pa.

“After reading Editor-in-Grief,” reports Corinne Hayes, 306 Blackstone Ct., Sioux Falls, S. D., “I took the book to school and had my teacher read it to the class.”

So much for the School club. You see what the other fans are doing. So why don’t you take one of your favorite books to school and have it read aloud, thus entitling you to membership in this club?

It may surprise you to learn that we have upwards of 10,000 members in our Freckled Goldfish club. In fact, by the time this book is published we may have close to 12,000 members. Yes, sir, our Goldfish club is something to talk about! On top of the general membership we have several hundred branch clubs, all of which are providing boys and girls with added fun. I have attended meetings of such clubs, and I want to tell you that the young organizers of these clubs know their stuff. A boy or girl who can get up a club like that, and make a success of it, is a real leader. And if you want to be a leader, here’s your chance to show what you can do.

Poppy Ott started the club. He and Jerry had a similar club in their book, Poppy Ott and the Freckled Goldfish. Even before the book was published informed young letter pals of mine were asking me if they could get up branch clubs. That gave me an idea. Why not organize a national club, calling it the Secret and Mysterious Order of the Freckled Goldfish, taking in members from coast to coast? “Fine!” said my publisher, when I presented the idea. So membership cards designed by Bert Salg were prepared, and soon the requests for membership began to roll in. Members then wanted pins. Which we provided. Then we published a little booklet, called a ritual, to help boys and girls who want to organize branch clubs.

To join the club simply observe the following rules:

(1) Print your name plainly.

(2) Supply your complete printed address.

(3) Give your age.

(4) Enclose two two-cent United States Postage stamps.

(5) Address your letter to

Leo Edwards,

Cambridge,

Wisconsin.

Remember that each new member receives a unique membership card designed by Bert Salg, the popular illustrator of these books. Containing a comical picture of Poppy’s Freckled Goldfish, together with our secret rules (the picture and the rules are printed on the card), each card also bears my own personal autograph. Also each member receives a club pin, thus distinguishing him as a Freckled Goldfish.

As I say, many initial members wanted to organize branch clubs. Permission was granted in each case. And now we have a printed ritual which any boy who wants to start a Freckled Goldfish club in his own neighborhood can’t afford to be without. This booklet tells how to organize the club, how to conduct meetings, how to transact all club business, and, probably most important of all, how to initiate candidates.

The complete initiation is given, word for word. Naturally these booklets are more or less secret. So, if you send for one, please do not show it to anyone who isn’t a Freckled Goldfish. The initiation will fall flat if the candidate knows what is coming. Three chief officers will be required to put on the initiation, which can be given in any boy’s home, so, unless each officer is provided with a booklet, much memorizing will have to be done. The best plan is to have three booklets to a chapter. These may be secured (at cost) at six cents each (three two-cent stamps) or three for sixteen cents (eight two-cent stamps). Address all orders to Leo Edwards, Cambridge, Wisconsin.

“I’m glad you enjoyed attending the meeting of our club,” writes Betty Henszey, Oconomowoc, Wis. “The next morning at school a bunch of kids almost wrecked me for not telling them you were coming. They were at the high school for manual training, but would have come down in time to meet you if they had known about it.”

“Our club is coming fine,” reports Gold Fin Tom Lincoln, Bentonville, Arkansas. “We’ve had one regular meeting and one initiation. We don’t want a big club. Six or seven members will be enough.”

“As soon as I get my membership card,” reports Glen Whitaker, 4105 College Ave., Kansas City, Mo., “I am going to organize a branch club. I have three members including myself. The meetings, except initiations, will be held under our roomy back porch. The initiations will take place in the basement. I’m wild over your books.”

“I was recently made a member of the Freckled Goldfish club,” reports Edward Bennett, 12 McKinley St., Bronxville, N. Y. “It certainly is a dandy club. Now I’m sending stamps for a ritual so that I can organize a local club.”

“I’m writing to let you know how our chapter is getting along,” reports Charles Klein, 1931 East 29th St., Brooklyn, N. Y. “It’s working out swell. Instead of appointing myself Gold Fin I got the members together and then let them vote. In that way I was elected Gold Fin and Clem Carey Silver Fin. We have no Freckle Fin because we have only five members. However, we have a fine time. Seeing that we have no regular place like a barn or something like that for a club house each member gives a meeting at his home one night a week.”

“I am the ‘Red’ in our gang,” reports Ralph Combs, Jr., 6254 Magnolia Ave., St. Louis, Mo. “For our club headquarters we use an old chicken house that was nicely cleaned out. We have four members so far. I have a dog named Pat and would like to know if he can be the mascot of the club.”

Sure thing, Ralph. I think that Pat will make a swell mascot.

“It has been a long time since I wrote to you, and plenty has happened since then,” reports Gold Fin Bob Halligan, 9201 107th Ave., Ozone Park, L. I., N. Y. “The first thing of importance was our second Hallowe’en party, one of the tickets of which is enclosed. I did all the printing at school. Not bad, eh? We took in five dollars, one of which was spent for prizes. Arguments frequently arose at our club meetings regarding who had and had not paid dues. So I printed a ‘due’ slip, and now we have no more arguments, as the slip of each member shows his standing. We now have seventeen dollars in the treasury. Not bad, considering that we spend something every week for refreshments.”

“We have started our club and hold our meetings in my room,” reports Everett Maloney, 119 E. 78th St., New York, N. Y. “On meeting nights I move everything out of the room except my bed, then we hang sheets on the walls and pull down the blinds, turning on a few lights which are all inside white sheets.”

Which will conclude our “Chatter-Box” for this time. But others will be coming along shortly. So, if you want to be represented, the thing to do is to write to me right away.

Leo Edwards,

Cambridge,

Wisconsin.

Here is a complete list of Leo Edwards’ published books:

THE JERRY TODD SERIES

THE POPPY OTT SERIES

THE TRIGGER BERG SERIES

THE ANDY BLAKE SERIES

THE TUFFY BEAN SERIES

It was a sunny summer’s day. Just the right kind of a day for a swim. So I lit out for Red Meyers’ house, intending to go from there to our new swimming hole on the edge of town. Oddly though Red’s house was closed. And the same was true of little Rory Ringer’s house in the same block.

Red and Rory are members of my lively gang. I’ve known Red all my life. When we were smaller we used to pitch rotten apples at each other over the back-yard fence. And never will I forget the day that he socked me with a pumpkin. Sweet essence of sauerkraut! But he got the worst of it in the end. For his ma had bought the big pumpkin for a Hallowe’en party. And what she did to the freckled family nest-egg when she found the wreckage of her prized party decoration in the gutter was nobody’s business.

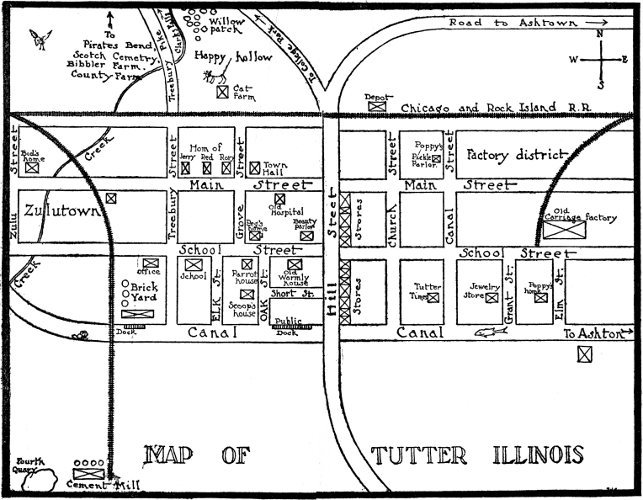

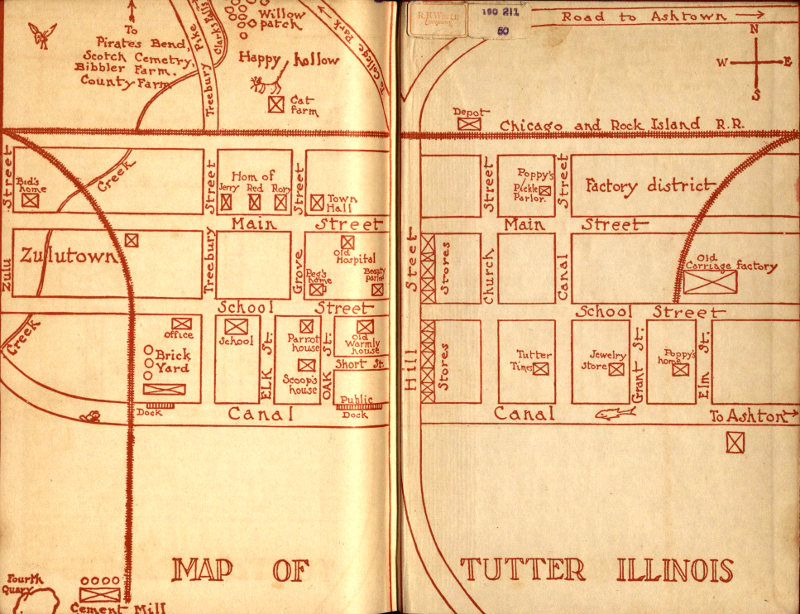

Like me, Red was born in Tutter, Illinois, which, I might add, is the swellest small town in the whole United States. My dad owns a brickyard while his dad, who has a glass eye and a Ford, runs a motion-picture theatre. The brickyard was started years ago by my Grandfather Todd, who, after the Civil War, came back to Tutter with a medal, a peg-leg and a big ambition to organize a business of his own. Some day, I suppose, I’ll be a brick maker like Dad, who learned the business from his father. But I’m too busy right now having a good time to think about future brick making. Still it will be fun when I do get to be a regular brick maker. For I have a swell dad. And I know that I’m going to enjoy working with him.

I might add, too, that I have a swell ma. And can she fry liver and onions! Um-yum-yum! The mere reference to it makes my mouth water. Loving her, I frequently wipe dishes for her. And often I make my own bed.

Red though, whose temper is as fiery as his hair, never made up a bed in his whole life. And if he were to offer his services with a dish towel I dare say his ma would faint. To hear her tell it he’s the laziest boy in town. All he does, she says, in her fat puffing way, is to eat and track in mud.

A warm friend of Mother’s, she often pops into our house to get the latest news. It’s fun to listen to her. For she wheezes and squeaks even worse than her fat widowed sister, Mrs. Pansy Biggle, who runs a beauty parlor on School Street.

If you have read my book about the “Stuttering Parrot” you’ll remember Aunt Pansy. Having lost her husband, who fell into the Illinois River and forgot to come up for air, she now lives at Red’s house where she divides her time (so he says) between her beautifying business and bossing him around. It was her goofy parrot that caused us so much grief. I thought of the simple-acting parrot as I cut across the lawn to Rory’s house. Little did I dream though, as I tripped over a croquet arch, that I was soon to be messed up with the parrot in another wild adventure involving a blind ghost, a silver skull and, most amazing of all, an animated wooden cow.

As a matter of fact the parrot had already disappeared, and with it Cap’n Tinkertop’s ring-tailed monkey, as I was to learn, with mounting surprise, later on.

Rory Ringer is the funniest kid that I ever listened to. Raised in England, he calls owls “howls” and hawks “’awks.” At school he keeps the reading class in an uproar. For you can readily imagine how such tangled-up pronunciations as “howls” and “’awks” would be received by a bunch of lively American schoolboys. “Rory Ringer, the ’ick from the hupper hend of Hengland where the blasted bloomin’ ’unters make ’atchet ’andles hout of bloody hoak.” That’s the kind of stuff we hung on him when he first came to town. But he didn’t mind it, jolly little wart that he was. And now, as I say, he’s one of my bosom pals.

Other members of my gang are Scoop Ellery, the leader, and big Peg Shaw. Also I have a chum by the name of Poppy Ott, around whom I have written a separate set of books. Good old Poppy! He and I have had piles of fun together. We’ve solved a number of odd mysteries, too, involving “Prancing Pancakes,” “Galloping Snails” and “Tittering Totems.” Yes, sir, Poppy is a swell guy. And as smart as a whip. With his help I dare say that we would have solved the new mystery of the silver skull and singing tree a whole lot quicker than we did. But he couldn’t help us, as I learned later on, for he was out of town.

Puzzled by my discoveries at Red’s and Rory’s homes, both of which had the outward appearance of having been temporarily abandoned, I lit out for Scoop’s house on Elm Street.

“Where’s the ’atchet-’andle guy from the hupper hend of Hengland and his big-mouthed confederate?” I inquired, as I tumbled into the wood shed.

The leader, I then observed, as I coughed up a bug, was fooling around with a pair of old football shoes to the soles of which he had glued felt pads.

“I’m going ghost hunting,” he explained, when I dismissed Red and Rory from my mind and started asking other natural questions.

“Ghost hunting!” Still, I told myself, as I curiously inspected one of the padded shoes, it was like Scoop, fun-loving, happy-go-lucky kid that he was, to think up a scheme like that.

He makes a swell leader. For he has a lot of peachy ideas. Which isn’t saying though that all of his schemes work. Suffering cats! If you must know the truth of the matter he’s gotten us into hot water more than once. But that’s all right. Even Napoleon, capable leader that he was, made a few mistakes, as history admits.

Scoop then brought out another pair of padded shoes.

“They’re for you, Jerry Todd,” he said, handing them to me.

“And what am I supposed to do?” I cheerfully fell in with his crazy notion. “Hang to the ghost by the seat of its pants while you carve your initials on its windpipe?”

“This is a blind ghost,” he spoke gravely.

I thought, of course, that he was putting on. For he’s full of truck like that. Anyway, as everybody knows, there’s no such thing as a real ghost, blind or otherwise. So a dickey-bird hunt would have been less nonsensical. Still, I told myself, as I studied his sober face, he had something up his sleeve.

I was curious now.

“Is there a new ghost in the neighborhood?” I began to quizz him.

He nodded.

“Where does it hang out?” I further inquired, with mounting curiosity.

“In the old Grendow place.”

“Br-r-r-r!” I shivered, as I balanced myself on a stick of stove wood. “Don’t tell me that it’s the ghost of old Adam Grendow himself.”

It takes a lot of queer people to make a world. And if what I have heard about old Adam Grendow is true he undoubtedly was one of the queerest men that ever lived. An Englishman, like Rory, he had built himself a big rambling house on the edge of town. And there he had lived for years. Strange men frequented his place. But it was noticeable that the unknown visitors came at night. The neighbors wondered at this. And they further wondered, with mounting uneasiness, at the roving lights in the big house. Why, they asked among themselves in awed whispers, did the odd master of the secluded place go nightly from the basement to the attic with a lamp in his hands? And what was the meaning of the eerie metallic sounds that occasionally reached the outside world through the open doors and windows?

Small wonder indeed that strange stories grew up about the stoop-shouldered, eagle-eyed master of Grendow Hall, as the place was called in true English custom. Some said he was an inventor of firearms, still in the employ of the English war department. His nightly callers were government agents. Other people in the neighborhood, of more imaginative turn of mind, declared that he was a wizard. His callers, they said, with frightened faces, were spirits from another world.

Not until he was killed in a motor-boat accident, following a wild midnight dash to Ashton, the county seat, was it learned that his only son was a notorious English counterfeiter. Caught in this country he was taken in hand by federal agents shortly after his father’s tragic death. Though still in his early twenties he was conceded to be one of the cleverest engravers in the world. And great indeed was the relief of the agents concerned when the federal prison doors closed behind him.

All this I had heard from Dad. And I had heard, too, that for years the federal agents had tried to round up the prisoner’s European accomplices. But no added arrests were made. Nor were any of the counterfeiting dies or coin presses ever confiscated.

The arrest that followed old Mr. Grendow’s tragic death started whispers that he, too, had been engaged in the manufacture and distribution of counterfeit money. This, the excited neighbors declared, fully explained the old man’s odd nightly activities. His secret visitors, much less than being government agents or spirits, were merely confederates. It was learned though that these men were jug buyers. Instead of being rich, as the neighbors suspected, old Adam Grendow had to make jugs, like his father before him, to earn a living.

People had wondered why the Englishman had built his house over a clay deposit. But now they knew the truth of the matter. A search of the house, following its owner’s accidental death, revealed a secret tunnel, through which the needed clay had been brought into the basement. Here, too, were many odd home-made pottery wheels. And a further search of the attic disclosed an immense stock of completed jugs.

Thus was the mystery of the roving lights cleared up.

The discovery of the machinery and completed jugs furnished material for much added excited talk among the neighbors. And it was known, too, that the federal agents had closed the place with definite disappointment. All efforts of theirs to connect the old jug maker’s activities with those of his misguided son had failed. Nor did the officials succeed in gaining any incriminating admissions from the prisoner himself, either before or after his hastened trial.

Considering the fact that Grendow Hall had been closed for years, it isn’t surprising that I stared at Scoop when I learned, as recorded, that he had been hanging around there on the sly. For it was still believed by the uneasy neighbors that the sinister unfrequented place, now sadly in need of repairs, still held strange brooding secrets. For instance, what had become of the jug buyers? Why had they never come back? And why had the old man worked secretly?

Was it pride? Did he want his neighbors to think that he was a landed gentleman, like others of his kind across the Atlantic? Many of the neighbors thought so. Yet others, confident that the mystery had been only partially cleared up, still awaited exciting developments.

Well, the humorous thought now shoved itself at me, as I further balanced myself on the stick of stove wood, if Scoop had taken the mystery in hand, capable leader that he was for the most part, there undoubtedly would be plenty of “developments.”

Nor was it improbable that another Juvenile Jupiter Detective by the name of Jerry Todd would find himself in hot water up to his neck.

But that was all right with me. Scoop, I saw now, wouldn’t have fixed up the padded shoes if he hadn’t gotten track of something. And regardless of what the consequences would be if we set forth on another mystery-solving adventure, I was ready, as the saying is, to follow in his padded footsteps to the last ditch.

I kind of hoped though that I wouldn’t land in the ditch on my snout.

Did you ever hear of the Juvenile Jupiter Detective association? We never did until an old shyster by the name of Mr. Anson Arnoldsmith came to town and sold us memberships in his organization at a dollar and a quarter a throw. He seemed like a nice old gentleman. So we believed every word he told us, even that crazy yarn of his about the mummy itch. It was learned later though that he was an old fraud. And so far as I know there is no real Juvenile Jupiter Detective association. But that doesn’t keep us from doing real detecting, as my various books prove.

So now you know why I called myself a Juvenile Jupiter Detective in the preceding chapter.

Our chief competitor in the local detecting business is Bill Hadley, the Tutter marshal. Bill almost laughed his homely head off when he learned about our new detective badges. Boy detectives! Haw! haw! haw! That, he said, in his rough way, was his idea of a big joke. But we soon proved to him that boys were just as capable of solving mysteries as men. In fact, if it hadn’t been for us I dare say that the mystery of the “Whispering Mummy,” in which Mr. Arnoldsmith was criminally involved, never would have been solved.

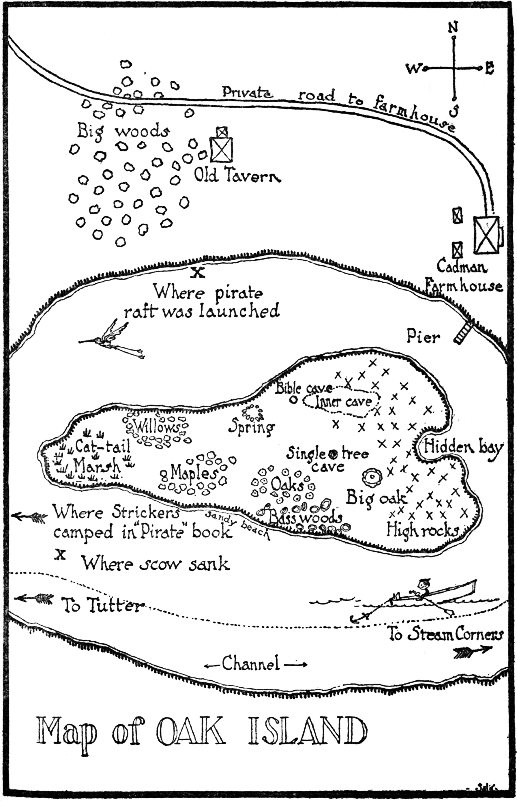

Next we got mixed up with a strange “Rose-Colored Cat.” Here we recovered some very valuable pearls. Then came that memorable trip to Oak Island, where we helped to bury and later recover what at that time we called the “Oak Island Treasure.”

This mystery solved, we tackled the weird case of the “Waltzing Hen.” Who was the strange yellow man who died so mysteriously in the Tutter hotel? A believer in transmigration, had he indeed turned into a yellow cat? And why did the odd brown hen waltz? We found out! Next we helped young Tom Ricks save his father’s invention, a “Talking Frog,” from thieving hands. Here is where we had our first experience with a “ghost.” Nor did any of us at the time, as we crouched breathlessly behind barred doors, suspect for a moment that the eerie gliding visitor on the outer porch wasn’t a sure-enough ghost. Gosh! From what we saw of it through the keyhole it sure looked ghostly enough to satisfy anybody. And even worse for me, it caught me outside of the house and ran me ragged.

Then came the more nonsensical mystery of the million-dollar “Purring Egg,” with its bewildering hilarious tangles and final astounding surprises, and after that the strange case of the man with the sleeping toe. We found him living in a “Whispering Cave.” This case took us back to Oak Island, where the treasure that I have mentioned had been earlier buried and recovered.

Having solved the “Sleeping Toe” mystery, it was time, Scoop said, for a vacation. So he and I, together with Red and Peg, set out on a camping trip. Stopping overnight at an old abandoned tavern called The King’s Silver we learned things from a strange persecuted boy that literally raised the hair on our heads. It was in this same old tavern, with its queer hidden secrets dating back to colonial days, that we found the pirate clothes used so effectively in our later sea battle with the enemy. To feel more like real pirates we gave ourselves pirate names such as Buzzard Bill the bloody butcher of the bounding billows (that was me), Wall-eyed Willy the wicked weasel of the wharves (that was Red), Hack-’em-up Hank the howling horror of the horizon (that was Scoop), and Cap’n Kidd (who was Peg). Talk about fun! Our “cannon” was a big sling-shot mounted in the middle of a raft. And for ammunition we used rotten eggs rolled in clay.

More recently we had solved the mystery of the “Bob-Tailed Elephant,” a case that had baffled detectives for months. Can you imagine a boy disappearing into thin air? Well, that’s what happened to Henny Bibbler. Even more astounding, the same thing happened to Red’s elephant.

MAP OF TUTTER ILLINOIS

Here again we proved our ability. But what a mess we got into when we tried publishing a newspaper. Suffering cats! Having survived this case, with its tangles and complications, I’ve made up my mind never to be a newspaper editor. Detecting is much safer. Still we had a lot of fun. And better still we were privileged to help an old man in distress, for which we had been promised a motor boat by his wealthy sister.

Peg, I might say here, is bigger than the rest of us. He eats more, I guess. Anyway he’s a head taller than Scoop and I. Of the same age, we’re all in the same grade at school, even Red and Rory, who share the distinction of being the smallest members of my gang.

But don’t get the idea that they’re any the less effective because of their abbreviated size. Red has gab enough for a giant. As for Rory, when once aroused he can fight wildcats. That’s why we’re considered the town’s chief gang, having licked Bid Stricker’s gang many times.

Bid lives in Zulutown, which is the name that the Tutter people have for the tough west-side section beyond Dad’s brickyard. Chief in the opposing gang are Jimmy Stricker, Bid’s cousin, and the two Milden brothers, Chet and Hib. The concluding member, all Zuluites, is Jim Prater, whose mouth is so big that he has to put clothespins on it to keep from turning inside-out when he yawns. A crummy outfit, if you were to ask me. Jealous of us, because we’re the smartest and have the best ideas, they like nothing better than to smash up our stuff. So don’t be surprised if they show up later on in my story.

Scoop told me then, as we further fooled around in the wood shed, about a native south-sea islander, who, though blind, could detect the approach of enemies a rod away. Nature, in depriving him of his eyesight, had given him this added hearing. It was all a part of a book, Scoop said.

“But what’s that got to do with padded shoes!” I inquired.

“As I told you,” the leader resumed, “the ghost that we’re going to hunt to-night is blind. Very probably it, too, has double hearing. So if we expect to creep up on it and capture it the less noise we make the better.”

“I can’t go,” I spoke quickly.

“And why not?” came the disappointed inquiry.

“I’ve got to stay at home,” I grinned, “and teach the cat how to purr.”

“Whose cat?”

“Mine, of course.”

Scoop gave a funny little laugh.

“Then you haven’t heard?” he inquired.

“Heard what?” I countered.

“About Red and Rory. They left town this afternoon in a big rowboat with your cat, Red’s aunt’s parrot, Cap’n Tinkertop’s monkey, Peg’s dog and Mrs. Maloney’s goat.”

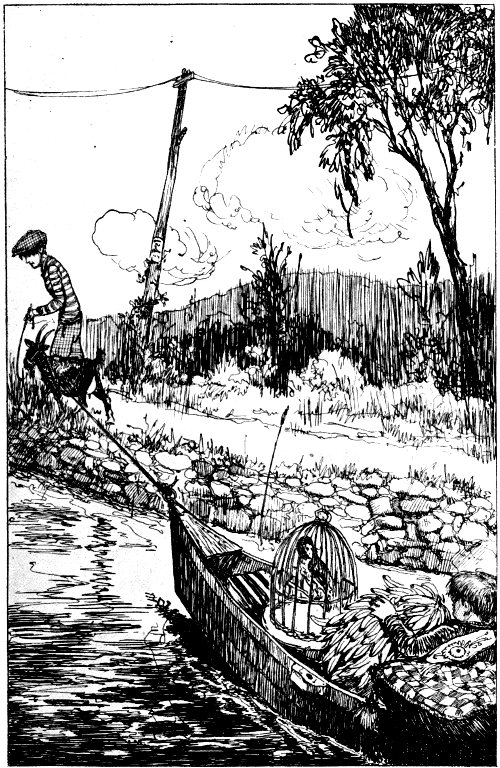

It was Scoop’s further story that Red and Rory were going to live in a cave, having gotten the idea from a book called The Flint Worker. And now undoubtedly they were halfway to Oak Island.

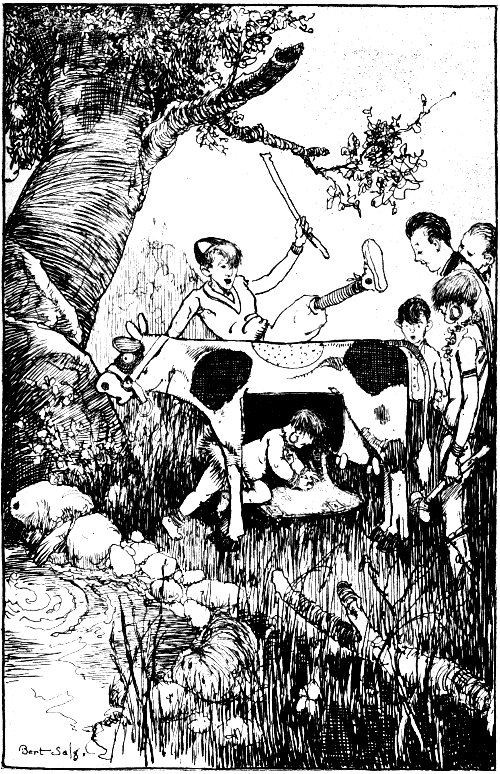

RED AND RORY WERE GOING TO LIVE IN A CAVE.

Gosh! This latest stunt of Red’s was about the craziest thing that I ever had heard tell of. And for the life of me I couldn’t comprehend why he had lugged along a boat load of dogs and cats, unless it was that he intended to roast them over an open fire in true caveman style. But the chances were, I saw, that he and Rory, who follows wherever Red leads, would have a peck of fun. And I suddenly wished that they had taken me along. For Oak Island, with its caves and hollows, is a darb of a place.

“If you must know the truth of the matter,” Scoop then told me, when I freely expressed my feelings to him, “I really think that Red expects us to follow him. And we may in a few days. But we can’t go now. For we’ve got a job on our hands.”

“Tell me the truth,” I sought his eyes. “Are you really going to hunt ghosts to-night?”

“Sure thing,” he grinned. “And you’re going with me.”

“How about Peg?” I further inquired.

“It’s only a small ghost,” I was told. “So I think that the two of us can handle it without difficulty.”

“How do you know it’s small?”

“Because I saw it last night.”

“In Grendow Hall?”

“Sure thing. It was sliding down the banister of the main staircase.”

Huh! As though I would believe that.

“And what were you doing?” I stiffened. “Playing leapfrog in the parlor?”

That brought a laugh.

“Didn’t you know Jerry, that the Strickers locked me in the old house yesterday afternoon?”

I shook my head.

“They caught me at the new swimming hole. Bid, it seems, had earlier seen lights in the old house. He thought it was ghosts prowling around. So to scare me he dumped me through a kitchen window. Worst of all he hid my clothes. So I had to stay there till dark. And it was then that I saw the blind kid.”

I heaved a sigh.

“Then it wasn’t a real ghost after all?” I spoke with relief.

“I thought it was a ghost at the start. But I changed my mind when it started sliding down the banister. No real ghost, I told myself sensibly, would do that. Besides I could tell from the slider’s actions that he was blind. Then, to my surprise, he disappeared in the twinkling of an eye. One minute he was standing at the head of the stairs, having suspected, I guess, that hidden eyes were watching him. And in the next minute he was gone. So I’m not so sure that he wasn’t a ghost after all.”

“Boloney!” I scoffed.

A reflective look crossed Scoop’s face.

“Was there ever a little boy in the family, Jerry?”

“Not that I know of.”

“I wonder who he is,” came the added reflective remark.

“Probably some tramp,” I suggested.

“But why is he hiding there? And where did he come from?”

“You should have questioned him before he disappeared.”

“That’s a queer house, Jerry,” Scoop went on. “It has a queer history. And while it’s possible, as you say, that the kid is an ordinary tramp, I can’t shake off the feeling that he in some way is connected with the place. In any event it strikes me that it’s our duty as Juvenile Jupiter Detectives to investigate the matter. If he is a tramp the owner of the place ought to be notified. And if he belongs there, through some family connection, it will be interesting to find out why he’s there. It may be a case of buried treasure, Jerry, put there in some out-of-the-way place by the original owner. Think of that! Oh, baby! I can hardly wait till to-night.”

“Let’s go now,” I suggested, with similar eagerness.

“No,” the leader shook his head. “It will be best to creep up on him in the dark. And with these shoes,” he indicated, “we can do it, too.”

It was on the tip of my tongue to tell him that he was goofy. For I could see no sense in wearing padded shoes. That was pure monkey-work. But he knew his stuff. So I decided to keep shut. Anyway it would be fun to pretend that the padded shoes were necessary.

We talked further about the old house, speculating on its probable secrets and wondering why the dead jug-maker’s relatives never had attempted to utilize or dispose of the property. And there were the jugs in the attic. They were worth considerable money, Scoop said. So the wonder was that tramps hadn’t appeared before this to steal them.

The more gab that we passed back and forth the more excited we became. Blind kids, we agreed, weren’t in the habit of running around the country alone. And least of all were they likely to be found in a place like this. The kid beyond all doubt had come here or had been brought here for a definite secret purpose. And it was our grim determination as Juvenile Jupiter Detectives to find out the facts of the case.

After which, very probably, if our services were no longer needed in Tutter, we would head for Oak Island to pay its new cave dwellers an extended visit. I could picture Red running around in a cat-skin breechcloth, or whatever you call it, with Aunt Pansy’s parrot perched on his bare shoulder. Regular Robinson Crusoe stuff. And there was the monkey and the goat.

Gee! I could hardly wait to join in the fun.

In separating, it was agreed between Scoop and I that we were to meet at his house at eight o’clock and then head directly for Grendow Hall on the edge of town. It was in this unfrequented locality that we had dammed a small creek, thus providing ourselves with a new swimming hole. And it was through here that Red and Rory had rowed that afternoon on their way to Oak Island.

Mother acted surprised when I came home that evening without Red.

“I thought you knew,” said she, as she bustled back and forth between the kitchen and the dining room, “that he’s going to get his meals here during his parents’ absence?”

“Where are they?” I quizzed, wondering how long it would be before she missed the cat.

“Oh, Mr. Meyers got the notion into his head that his glass eye was too small for its socket. It jiggled, he said. So he and Mrs. Meyers have gone to Peoria in their Ford to have the eye changed.”

This explained why the house was deserted. And in the further conversation I learned that Mr. and Mrs. Ringer were spending the week end in Springfield, where Mr. Ringer, a chemist, was planning to launch some kind of a new cockroach powder that he had invented. Rory had been told to stay at home and manage the house. But instead of obeying orders he had let Red coax him away, as recorded. And now, no doubt, they were twiddling the faucets of the goat’s milk supply in preparation for their first outdoor meal.

Still, I couldn’t quite picture Red guzzling goat’s milk. For he has pink spasms every time his ma makes him drink cow’s milk. And everybody knows what a goat smells like!

Mother was all upset when she learned that her red-headed charge had temporarily separated himself from civilization. Having promised to take care of him during his parents’ absence she was afraid that some dire calamity would befall him. I told her though that there was no cause for worry. Red, I said, was big enough to take care of himself. And if he found too many sand burs in the cave where he and Rory planned to set up housekeeping, they could easily put leather seats in their breechcloths.

I doubt though if Mother really knew what a breechcloth was. For she gave me a kind of dumb look. So to avoid possible complications I discreetly changed the subject.

Not until she went to supper that evening in a down-town restaurant did Aunt Pansy learn that both her red-headed nephew and her prized parrot had disappeared into the wilds of Oak Island. I heard afterwards that she fainted on top of a T-bone steak. In the confusion that followed someone turned in a fire alarm. Later they loaded her into a taxicab and brought her home, calling on Mother to take care of her. And wondering what the two would do when they learned that they both had lost pets, I lit out for Scoop’s house.

“Where was the fire?” he inquired, as I tumbled into the yard where he and his kid brother were playing mumbly-peg beside a potted rubber plant.

“It wasn’t a fire,” I told him. “It was Aunt Pansy. Someone told her in Mugger’s restaurant that Red had eloped with her parrot. And she fainted in the gravy bowl.”

“It must have been a big bowl,” grinned Scoop.

“Red’s having a swell time now,” I nodded. “But I’d hate to be in his shoes when his aunt gets hold of him. Or his ma either, for that matter.”

An advertisement in the local evening newspaper had attracted Scoop’s attention.

“Read that,” said he, handing me the newspaper.

I later made a copy of the advertisement. Here it is:

Lost, strayed or stolen—a small brindle donkey answering to the name of Shoe Polish. Last seen in canal tow-path between Haines Lock and Tutter. Reward. Address Mrs. Antonio Carmel, R.F.D. No. 6.

“It’s easy enough to figure out where the donkey disappeared to,” commented Scoop, when I put the newspaper aside.

“But how in Sam Hill did Red get it into the rowboat?” I puzzled.

“Don’t be silly. He probably rode it down the tow-path, or made it draw the loaded rowboat.”

“By the time we get there,” I laughed, “he’ll have a whole menagerie in his cave.”

“Maybe,” Scoop laughed in turn, “he’s planning to cross the donkey with his aunt’s parrot and raise flying horses.”

“I bet he took the pig, too,” little Jim Ellery then spoke up.

“What pig?” Scoop stared.

“Why, I heard my pa tell about somebody’s pig that came up missing between here and Ashton. And it was a mamma pig, too, with ten little pigs.”

Scoop got my eye.

“Suffering cats!” he squawked.

Slipping the padded shoes under our arms we then started down the darkening street. Pretty soon we came to the canal that threads its way through Tutter, Ashton and other near-by towns. It was by way of this canal that Red and Rory had reached Oak Island, itself a small body of land in one of the canal’s biggest wide-waters. And it was on the bank of this canal, on the edge of town, that Adam Grendow had built his odd home.

I dare say you all know what a canal is. This one, with its tow-path, winding narrow channel and over-hanging foliage, had the usual number of locks for maintaining the proper water level. Wide-waters were provided every few miles to accommodate passing barges. East of Ashton, which in itself is ten miles east of Tutter, there is a natural wide-waters. This small lake was a marsh before the canal was built. And what used to be an extensive wooded knoll in the middle of the marsh is now an island, high and rocky at one end and boggy at the other, with intervening hummocks and gullies.

Deriving its name from an outstanding tree, the island was recently purchased by a business associate of Dad’s, who plans some day to erect a swell summer home in the maple grove on the sandy south shore. Then, I suppose, we’ll have to find a new camping place. I’m hoping though that Mr. Cliffe, the new owner, delays the construction of his intended summer home for many years. For a sweller camping spot couldn’t be imagined. In the first place it’s wild and secluded. Few people ever go there. Now and then a passing tug stops to refill its water casks at the big spring on the rocky north shore. But that doesn’t happen very often. Added seclusion is provided by the densely wooded mainland, where, as recorded in my “Pirate” book, we met with such amazing adventures in the old tavern. This lonely, glowering building still stands, exactly as we left it. And in the surrounding forest is the usual thicket of berry bushes. Truly a boy’s paradise!

Years ago an odd old codger made his home on the island. People called him a hermit. He’s gone now. But the cave that he hewed into the soft sandstone east of the spring still stands. It was here that Red and Rory intended to make their home. And as I thought of them taking command of the pleasant island the longing again crept over me to join them.

But I quickly dismissed these thoughts from my mind, and got down to business in regular Sherlock Holmes style, when, after a brisk walk of ten minutes, we came within sight of a rambling, two-story gabled house at the opposite ends of which red-topped fireplace chimneys stood up above the roof peaks like odd furtive sentinels. For years these stony servants had stood there, unwarmed by either winter or summer fires, mindful of every human approach. They had seen us as we passed up and down the adjacent tow-path on our way to and from the new swimming hole. And often, no doubt, our natural boyish banter had disturbed their dignity. Now I could imagine that their stony eyes were filled with hatred as we guardedly turned in at the sagging gate. For they knew what was going on in our minds! And loyal to their departed master they were fearful, as they stood out against the diminishing light of the setting sun, that his long-hidden secrets would be revealed.

Stopping in the shadow of a scraggly lilac bush Scoop changed his shoes. I quietly did the same. And then, as the darkness further crowded in on us with a dank vapory touch, we guardedly circled to the back of the house and stopped before an open kitchen window.

“See anything?” I inquired, when the leader peeped inside.

“No,” was the curt reply.

The long-neglected yard was a tangle of trees and bushes, some of which had even shoved their leafy arms under the porch roof where we stood. And as I thought of the thousands of shadowy hiding places thus provided I couldn’t shake off the uneasy feeling that something beyond range of our eyes was covertly watching us. Was it indeed the fireplace chimneys? Still, my better sense triumphed, that was a crazy thought.

Then, as a twig cracked in the darkness, I almost jumped out of my skin.

“A rat,” Scoop spoke in an offhand way.

A rat! It sounded like an elephant to me; and I told him so.

“Don’t be silly,” he grunted, seemingly not the least bit afraid himself.

I wished then that we had brought Peg with us. For he is big and strong, as I say. And while I had no special fear of the blind kid himself, figuring that either Scoop or I could handle him alone, I still couldn’t shake off the increasingly uncomfortable feeling that something that wasn’t good for us was slowly but surely creeping in on us.

Then another twig cracked!

“If that’s a rat,” I told Scoop, ready to run whenever he gave the signal, “I’m a cross-eyed cockle bur.”

Even old strongheart looked kind of shaky at the thought.

“Let’s hide,” he suggested. And clutching my arm he drew me into the bushes.

But we didn’t stay there very long. For what do you know if a big tall thing with a vapory white body and burning eyeballs didn’t poke its hideous snout out of the bushes and “boo” at us.

Ghosts never did make a hit with me. And least of all did I care to get chummy with one that had the “booing” habit. So, instead of “booing” playfully in return, as might have been ethical under the circumstances, I lit out lickety-cut for home sweet home.

But that ghost was a sticker. Having taken a shine to me he had no intention of letting me get away from him. I could hear him zipping along behind me. And every moment or two he “booed” against the back of my neck.

Instead of padded soles, what I needed now, I told myself, as I further sliced the evening air with my nose, was a pair of winged shoes like the Mercury geezer, and nothing else but.

Having taken the lead as usual Scoop suddenly stopped beside the tow-path gate.

“Down!” he yelled at me, as I whizzed by him all of a sudden.

I hadn’t the slightest idea why he wanted me to stop. But he’s smart, as I say. And figuring that he had hit on some scheme to save me from the persistent ghost, who now was prodding me in the seat of the pants with a pronged stick, I dropped on all fours.

Had the ghost been real it would have floated over me in true supernatural style. Instead it stumbled over me like an old cow. And did I ever grunt as its big feet socked me in the ribs. Ouch!

“It’s Peg Shaw,” Scoop told me, when I staggered to my feet. “I recognized him the moment I got a peek at him. And I took this way of getting even with him.”

Having taken a header into the weeds, old hefty looked kind of sheepish when he limped into sight with a sprig of burdock draped on one ear.

The “vapory white body,” I then learned, was just a plain bed sheet. And what I had mistaken for “burning eyeballs” was merely painted holes.

Which shows you to what extent a fellow can be fooled by his imagination.

The upset didn’t half repay Peg for the mean trick that he had played on us. And we should have taken a poke at him. But it’s hard to be bitter with an old pal. So Scoop and I generously forgave him.

We had just uncovered another mystery, we said, as we crowded together in the path. There was a blind boy hiding in the big house. And confident that he could throw some light on the secrets that still hung over the old place, it was our intention as Juvenile Jupiter Detectives to corral and quizz him.

“But I was told,” said Peg, “that you came here to hunt ghosts.”