* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: A History of the United States

Date of first publication: 1909

Author: Charles Kendall Adams (January 24, 1835 – July 26, 1902); William P. (Peterfield) Trent (10 November 1862 – 1939)

Date first posted: Aug. 6, 2016

Date last updated: Aug. 6, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160804

This ebook was produced by: Larry Harrison, Cindy Beyer & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

GEORGE WASHINGTON

ALLYN AND BACON’S SERIES OF SCHOOL HISTORIES

A HISTORY OF

THE UNITED STATES

BY

CHARLES KENDALL ADAMS

LATE PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN

AND

WILLIAM P. TRENT

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE IN COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

REVISED EDITION

ALLYN AND BACON

Boston and Chicago

| ALLYN AND BACON’S SERIES OF |

| SCHOOL HISTORIES |

| 12mo, half leather, numerous maps, plans, and illustrations |

| ——————— |

| ANCIENT HISTORY. By Willis M. West of the University of Minnesota. |

| MODERN HISTORY. By Willis M. West. |

| HISTORY OF ENGLAND. By Charles M. Andrews of Bryn Mawr College. |

| HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES. By Charles K. Adams, and William P. Trent of Columbia University. |

| THE ANCIENT WORLD. By Willis M. West. |

| Also in two volumes: Part I: Greece and the East. Part II: Rome and the West. |

COPYRIGHT, 1903 AND 1909,

BY WILLIAM P. TRENT AND BY JOHN P. FISK,

L. S. HANKS, AND BURR W. JONES, EXECUTORS

OF THE ESTATE OF CHARLES KENDALL ADAMS.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

The lamented death of President Adams entails on me the duty of writing the preface to our joint work,—a duty which, had he lived, would naturally have fallen to him, since to his initiative and energy the volume owes its existence. Fortunately, the entire manuscript had the benefit of his wisdom and experience as teacher and investigator, and the proofs of about half the book passed under his watchful supervision.

Five years ago, in a letter to me proposing the book, Dr. Adams gave, among his reasons for wishing to add to the long list of school histories of the United States, three principal objects:—

First, to present fully and with fairness the Southern point of view in the great controversies that long threatened to divide the Union.

Second, to treat the Revolutionary War, and the causes that led to it, impartially and with more regard for British contentions than has been usual among American writers.

Third, to emphasize the importance of the West in the growth and development of the United States.

These objects have been kept constantly in view. We felt, moreover, that the development of institutions and government may justly be considered of great importance, although naturally lacking in picturesqueness, and we have endeavored to set in relief this evolutionary process. How far we have succeeded in accomplishing the objects sought remains for others to judge.

I cannot forbear to place on record here my appreciation of the fortitude with which Dr. Adams bore his protracted sufferings and did his work; of his conscientiousness in matters of minutest detail; of his fairness and sympathy toward those with whom he did not agree, and of the unfailing courtesy that marked every line of his correspondence.

Acknowledgment is due to the highly competent services of Miss May Langdon White of New York, whom Dr. Adams selected to assist in the revision of the work.

W. P. TRENT.

Columbia University,

New York, November, 1902.

| PAGE | ||

| List of Maps | xvi | |

| List of Illustrations | xvii | |

| Chronological Table | xx | |

| PART I.—PERIOD OF DISCOVERY AND | ||

| SETTLEMENT, 1492–1765. | ||

| CHAPTER I.—DISCOVERY. | ||

| SECTION | ||

| 1-3. | The American Indians | 1 |

| 4. | Pre-Columbian Discoverers | 4 |

| 5-13. | Columbus and the Spanish Discoverers | 7 |

| 14-16. | The French Explorers | 18 |

| 17-18. | The English Explorers | 20 |

| 19-20. | Summary of Results | 22 |

| References | 23 | |

| CHAPTER II.—THE FIRST PLANTATIONS AND COLONIES, 1607–1630. | ||

| 21-28. | The Settlement of Virginia | 24 |

| 29-30. | The Settlement of New York | 29 |

| 31-36. | The Pilgrims at Plymouth | 31 |

| 37-38. | The Settlement of Massachusetts | 34 |

| References | 36 | |

| CHAPTER III.—SPREAD OF PLANTATIONS, 1630–1689. | ||

| 39-41. | The Settlement and Growth of Maryland | 37 |

| 42-45. | Development of Virginia | 40 |

| 46-52. | Development of New England | 42 |

| 53-60. | The New England Confederacy | 46 |

| 61-71. | Development of the Middle Colonies | 51 |

| 72-76. | The Southern Colonies | 57 |

| References | 59 | |

| CHAPTER IV.—THE COUNTRY AT THE END OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY. | ||

| 77-78. | General Conditions | 60 |

| 79-84. | Characteristics of New England | 61 |

| 85-86. | Characteristics of the Middle Colonies | 65 |

| 87-90. | Characteristics of the Southern Colonies | 66 |

| References | 68 | |

| CHAPTER V.—DEVELOPMENT OF THE COLONIES, 1690–1765. | ||

| 91-94. | Colonial Disputes | 69 |

| 95-97. | Virginia and Georgia | 71 |

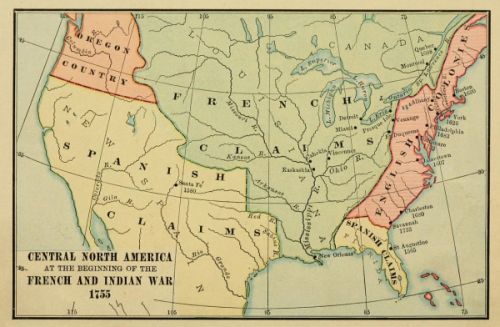

| 98-100. | French Discoveries and Claims | 73 |

| 101-116. | Wars with the French | 75 |

| References | 86 | |

| PART II.—PERIOD OF THE REVOLUTION, 1765–1789. | ||

| CHAPTER VI.—CAUSES OF THE REVOLUTION. | ||

| 117-120. | General Causes | 87 |

| 121-126. | The Question of Taxation | 91 |

| 127-132. | The Resistance of the Colonies | 93 |

| 133-135. | The Tax on Tea | 98 |

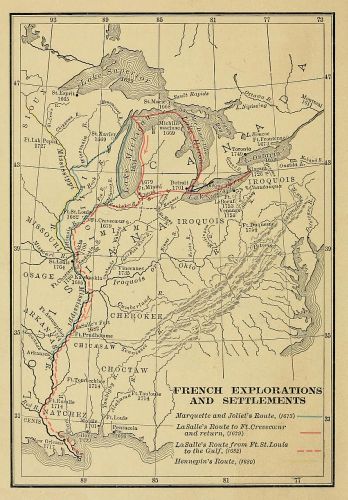

| 136-139. | New Legislation and Opposition | 100 |

| 140-143. | The Crisis | 103 |

| References | 106 | |

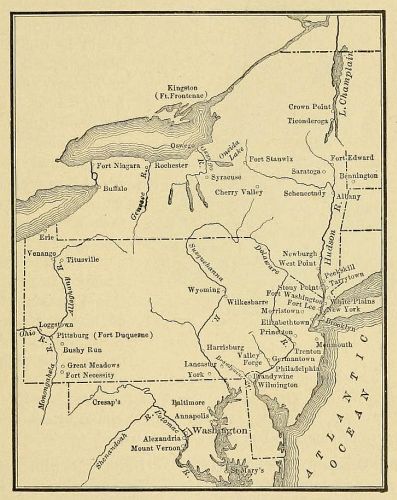

| CHAPTER VII.—THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1775 AND 1776. | ||

| 144-147. | Early Movements | 107 |

| 148-152. | Washington in Command | 110 |

| 153-158. | The War in New York | 114 |

| 159-160. | General Condition of the Country | 118 |

| 161-162. | Failure of British Expeditions | 119 |

| 163-165. | The Declaration of Independence | 121 |

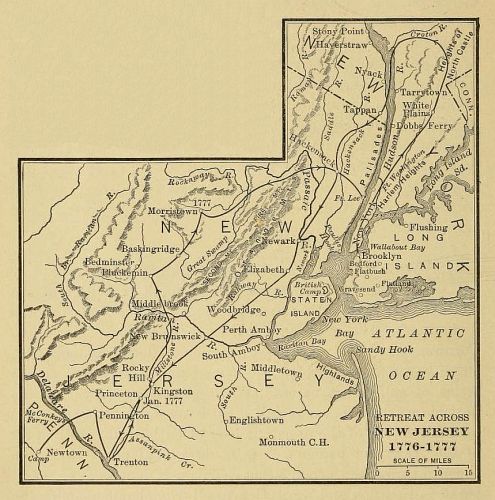

| 166-176. | The War in New Jersey | 126 |

| CHAPTER VIII.—THE CAMPAIGN OF 1777. | ||

| 177-187. | The Struggle for the Center | 135 |

| CHAPTER IX.—THE FRENCH ALLIANCE AND THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1778 AND 1779. | ||

| 188-193. | A Winter of Discouragement | 144 |

| 194-198. | Prospects Brighten | 149 |

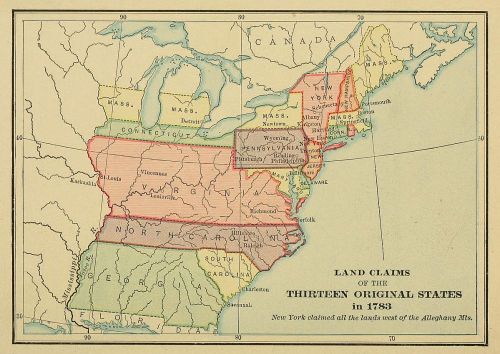

| 199-207. | Conditions West of the Alleghanies | 152 |

| 208-209. | The Conquest of the Northwest | 158 |

| 210-212. | The Victories of Paul Jones | 159 |

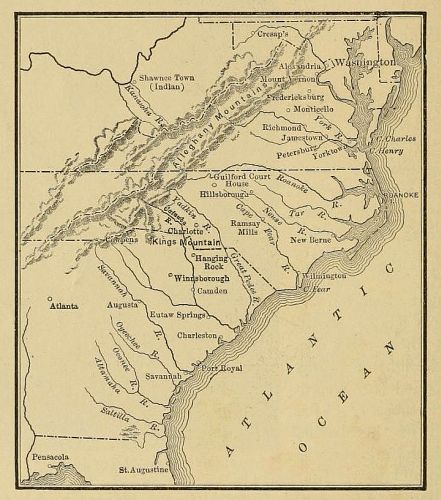

| CHAPTER X.—THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1780 AND 1781. | ||

| 213-214. | The War in the South | 162 |

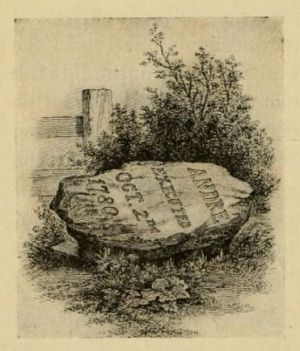

| 215-220. | The Treason of Benedict Arnold | 164 |

| 221-223. | Causes of Discouragement | 167 |

| 224-228. | American Successes in the South | 168 |

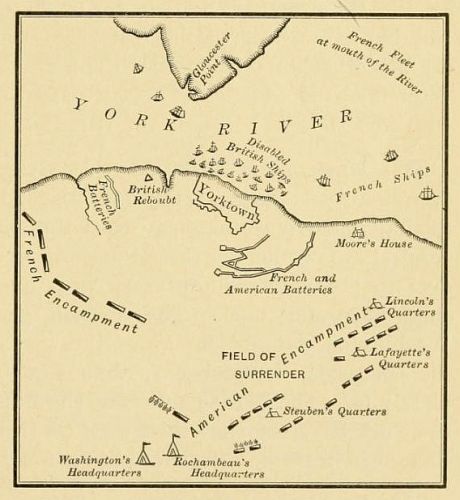

| 229-237. | The Close of the War | 172 |

| CHAPTER XI.—THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION AND THE CONSTITUTION. | ||

| 238-243. | Difficulties of Confederation | 178 |

| 244-256. | The Constitution | 181 |

| References | 190 | |

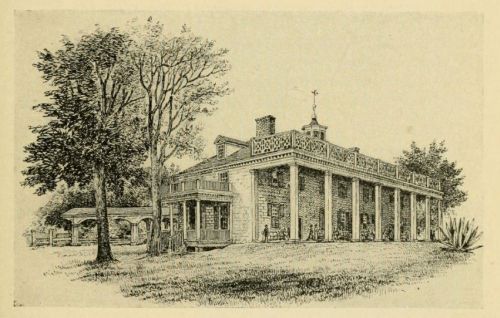

| PART III.—THE ORGANIZATION OF POLITICAL PARTIES, 1789–1825. | ||

| CHAPTER XII.—THE COUNTRY AT THE CLOSE OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY. | ||

| 257-262. | General Conditions | 191 |

| 263-264. | Spirit of the People | 194 |

| References | 195 | |

| CHAPTER XIII.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF WASHINGTON, 1789–1797. | ||

| 265-268. | Early Legislation and Parties | 196 |

| 269-274. | Difficulties of Administration | 200 |

| References | 204 | |

| CHAPTER XIV.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF JOHN ADAMS, 1797–1801. | ||

| 275-281. | A Period of Dissensions | 205 |

| References | 210 | |

| CHAPTER XV.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF JEFFERSON, 1801–1809. | ||

| 282-284. | Jeffersonian Policy | 211 |

| 285-295. | Measures and Events | 214 |

| 296-297. | Character of Jefferson’s Statesmanship | 222 |

| References | 224 | |

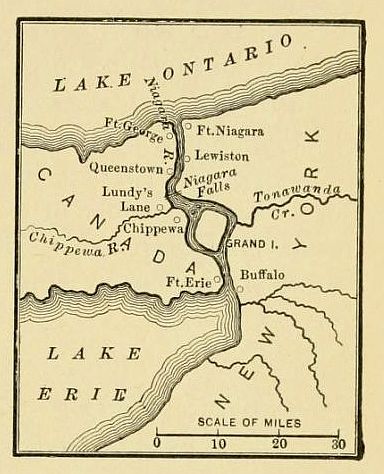

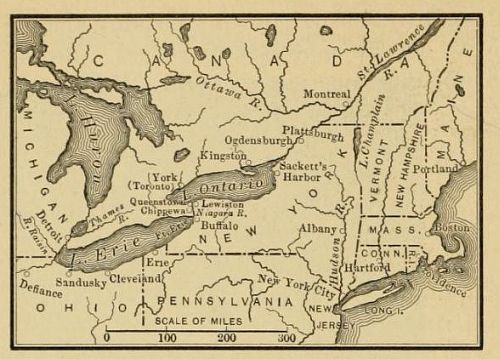

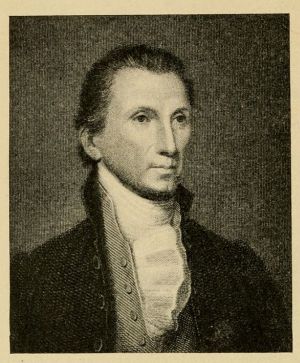

| CHAPTER XVI.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF MADISON, 1809–1817. | ||

| 298-303. | Outbreak of War | 225 |

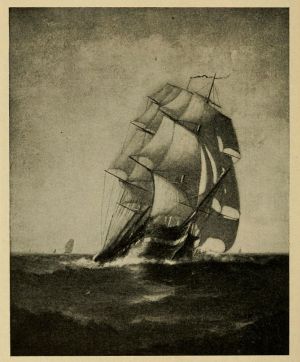

| 304-305. | Exploits of the Navy | 230 |

| 306-310. | Reverses and Successes | 234 |

| 311-312. | End of the War | 238 |

| 313-315. | The Disaffection of New England | 240 |

| 316-319. | Consequences of the War | 242 |

| References | 244 | |

| CHAPTER XVII.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF MONROE, 1817–1825. | ||

| 320-322. | Character of the Period | 245 |

| 323-326. | Diplomatic Achievements | 247 |

| 327-331. | Slavery comes to the Front | 250 |

| 332-334. | Factional Politics | 254 |

| References | 256 | |

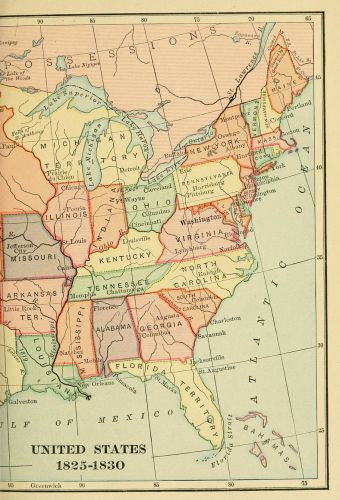

| PART IV.—SPREAD OF DEMOCRACY AND EXTENSION OF TERRITORY, 1825–1850. | ||

| CHAPTER XVIII.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF JOHN QUINCY ADAMS, 1825—1829. | ||

| 335-339. | Failures of the Administration | 257 |

| 340-342. | The Tariff Question | 260 |

| References | 262 | |

| CHAPTER XIX.—THE JACKSONIAN EPOCH, 1829–1837. | ||

| 343-345. | Political Conditions | 263 |

| 346-350. | Progress of the Nation | 265 |

| CHAPTER XX.—JACKSON’S FIRST ADMINISTRATION, 1829–1833. | ||

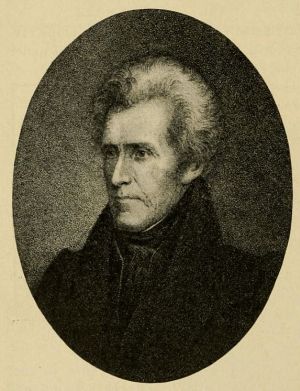

| 351-354. | A Popular Autocrat | 271 |

| 355-356. | The Debate over the Nature of the Constitution | 274 |

| 357-358. | The Tariff and Nullification | 278 |

| References | 280 | |

| CHAPTER XXI.—JACKSON’S SECOND ADMINISTRATION, 1833—1837. | ||

| 359-360. | The Abolitionists | 281 |

| 361-367. | Financial Disturbances | 283 |

| References | 287 | |

| CHAPTER XXII.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF VAN BUREN AND OF HARRISON AND TYLER, 1837–1845. | ||

| 368-371. | A Period of Confusion | 288 |

| 372-373. | The Embarrassments of the Whigs | 290 |

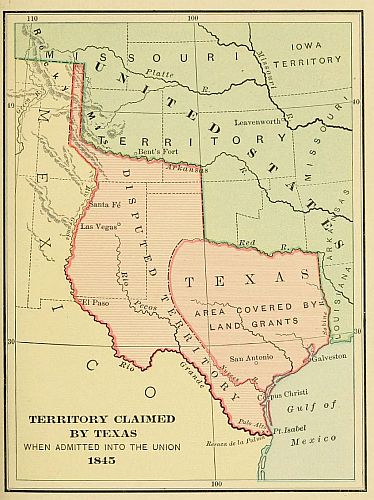

| 374-376. | Texas and Oregon | 293 |

| References | 295 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF POLK, 1845–1849. | ||

| 377-379. | The Opening of the Mexican War | 296 |

| 380-389. | The Conduct and Results of the War | 299 |

| References | 304 | |

| PART V.—THE EVE OF THE CIVIL WAR, 1850–1861. | ||

| CHAPTER XXIV.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF TAYLOR AND FILLMORE, 1849–1853. | ||

| 390-394. | The Question of California | 305 |

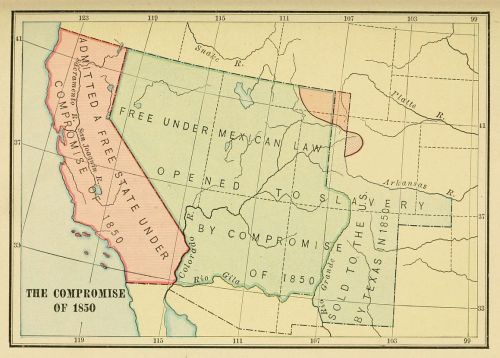

| 395-400. | The Compromise of 1850 | 308 |

| 401-404. | International and Domestic Affairs | 313 |

| CHAPTER XXV.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF PIERCE, 1853–1857. | ||

| 405-410. | The Confusion of Parties | 317 |

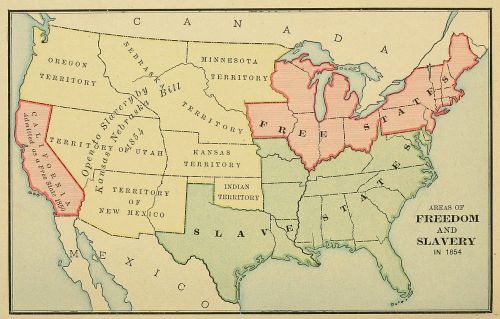

| 411-415. | Kansas-Nebraska Legislation | 320 |

| 416-417. | The Republican Party | 323 |

| CHAPTER XXVI.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF BUCHANAN, 1857–1861. | ||

| 418-422. | The Supreme Court and Slavery | 326 |

| 423-427. | Kansas and Utah | 329 |

| 428-431. | The Great Debates | 332 |

| 432-434. | John Brown and Public Opinion | 336 |

| 435-439. | The Presidential Campaign of 1860 | 339 |

| 440-446. | Secession of the South | 342 |

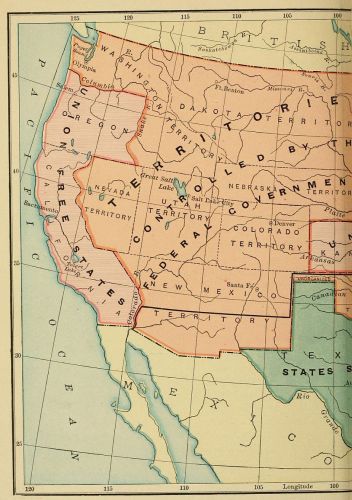

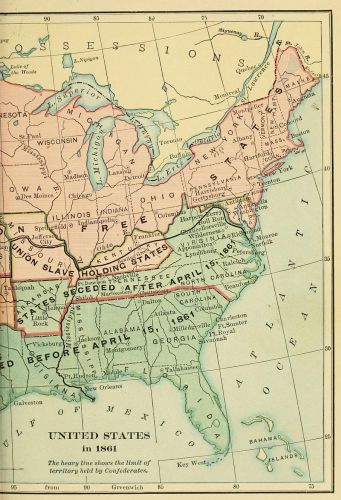

| 447-449. | The Country in 1860–1861 | 348 |

| References | 350 | |

| PART VI.—THE CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION, 1861–1869. | ||

| CHAPTER XXVII.—THE BEGINNINGS OF THE CIVIL WAR. | ||

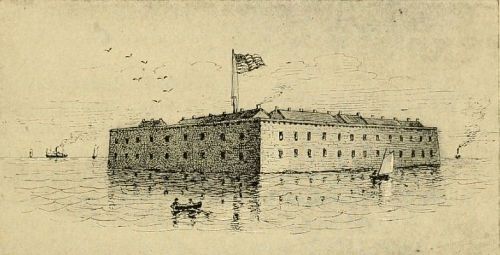

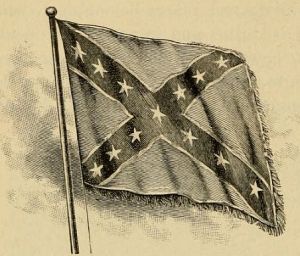

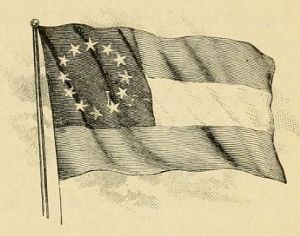

| 450-453. | Opening of Hostilities | 353 |

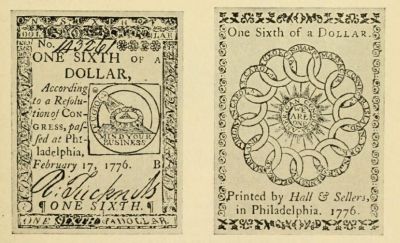

| 454-458. | Military and Financial Strength of the Combatants | 357 |

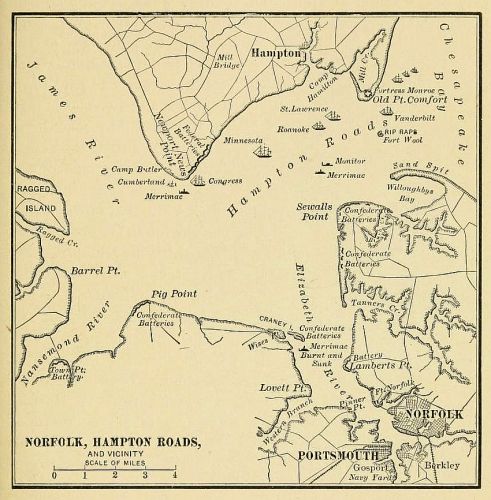

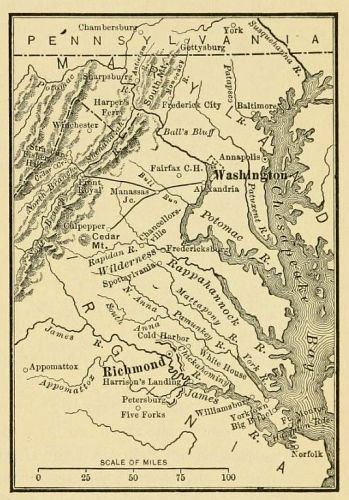

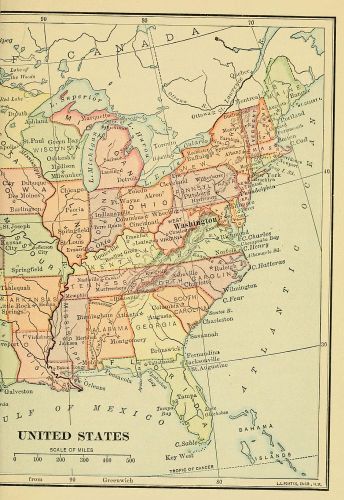

| 459-461. | Description of the Seat of War | 360 |

| 462-465. | Domestic and Foreign Complications | 362 |

| 466-471. | Military Movements of 1861 | 365 |

| 472-474. | International Difficulties | 369 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII.—THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1862. | ||

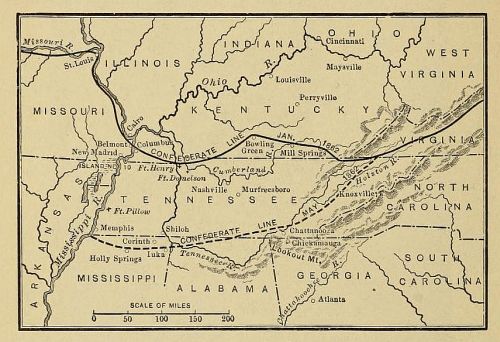

| 475-483. | The War in the West | 372 |

| 484-489. | The Work of the Navy | 381 |

| 490-498. | The War in the East | 387 |

| 499-502. | Public Feeling in the North and Great Britain | 394 |

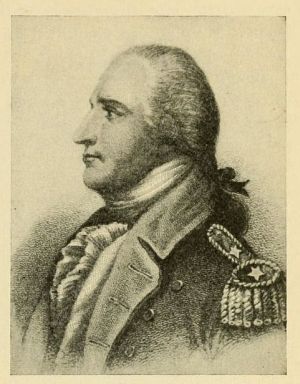

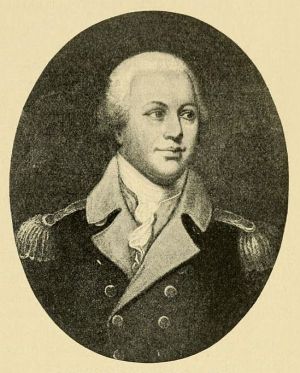

| 503-506. | The War in the East continued | 397 |

| 507-513. | Domestic and Foreign Effects of the Campaigns of 1862 | 402 |

| References | 406 | |

| CHAPTER XXIX.—THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1863. | ||

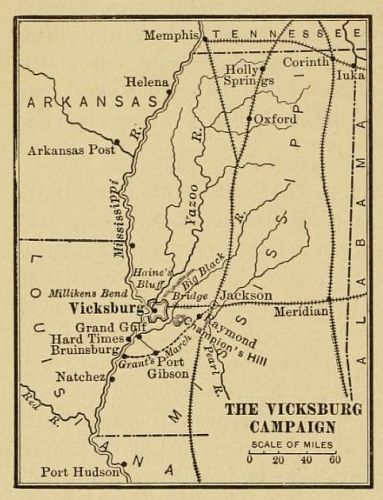

| 514-517. | Vicksburg | 408 |

| 518-522. | The Chattanooga Campaign | 411 |

| 523-525. | The Eastern Campaigns | 414 |

| 526-529. | Embarrassment of the Federal Government | 419 |

| References | 421 | |

| CHAPTER XXX.—THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1864. | ||

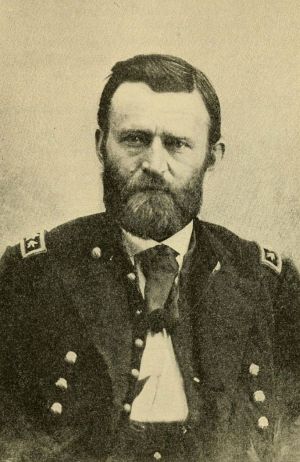

| 530-533. | Grant and Lee in Virginia | 422 |

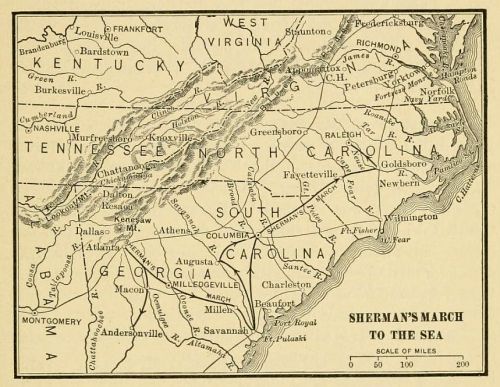

| 534-538. | Sherman’s Campaigns | 426 |

| 539-541. | Naval Victories | 430 |

| 542-546. | Political Affairs | 432 |

| References | 435 | |

| CHAPTER XXXI.—END OF THE WAR, 1865. | ||

| 547-551. | Movements of Sherman and Grant | 436 |

| 552-554. | The Death of President Lincoln | 440 |

| 555-561. | The Magnitude of the War | 441 |

| References | 445 | |

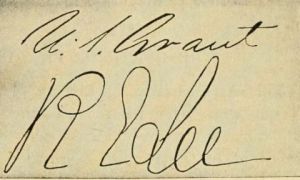

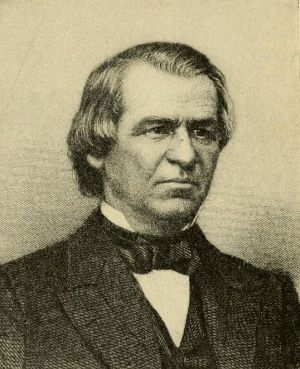

| CHAPTER XXXII.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF JOHNSON: RECONSTRUCTION, 1865–1869. | ||

| 562-573. | Different Policies of Reconstruction | 446 |

| 574-576. | Effects of Reconstruction | 452 |

| 577-580. | Johnson and Congress | 454 |

| References | 457 | |

| PART VII.—PERIOD OF NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT, 1869–1902. | ||

| CHAPTER XXXIII.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF GRANT, 1869–1877. | ||

| 581-588. | Grant’s First Administration, 1869–1873 | 458 |

| 589-595. | Grant’s Second Administration, 1873–1877 | 463 |

| 596-599. | Party Politics | 468 |

| References | 472 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF HAYES AND OF GARFIELD AND ARTHUR, 1877–1885. | ||

| 600-603. | Industrial Problems | 473 |

| 604-605. | Financial Problems | 475 |

| 606-609. | Political Affairs | 476 |

| 610-613. | Chief Features of Arthur’s Administration | 480 |

| 614-617. | Political Events | 483 |

| 618-619. | The Presidential Campaign of 1884 | 485 |

| References | 487 | |

| CHAPTER XXXV.—FIRST ADMINISTRATION OF CLEVELAND, 1885–1889. | ||

| 620-623. | Important Measures and Reforms | 488 |

| 624-628. | Industrial and Financial Disturbances | 491 |

| References | 494 | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI.—THE ADMINISTRATION OF BENJAMIN HARRISON, 1889–1893. | ||

| 629-638. | Domestic Events and Measures | 495 |

| 639-641. | Foreign Affairs | 500 |

| 642-643. | Political Affairs | 502 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII.—SECOND ADMINISTRATION OF CLEVELAND, 1893–1897. | ||

| 644-649. | Financial Legislation | 504 |

| 650-651. | Foreign Affairs | 507 |

| 652-655. | Domestic Events | 510 |

| References | 513 | |

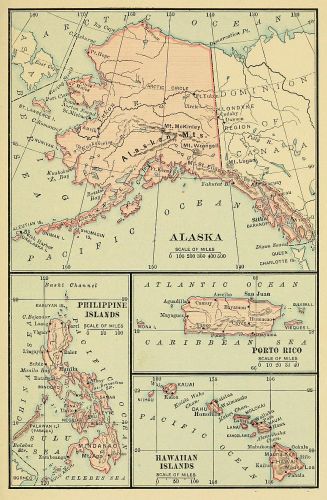

| CHAPTER XXXVIII.—THE ADMINISTRATIONS OF McKINLEY AND ROOSEVELT, 1897–1902. | ||

| 656-657. | The Beginning of McKinley’s Administration | 514 |

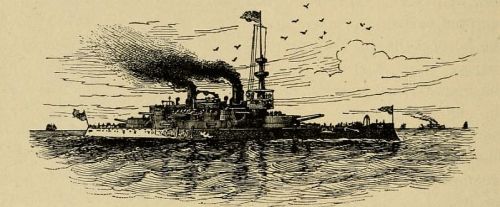

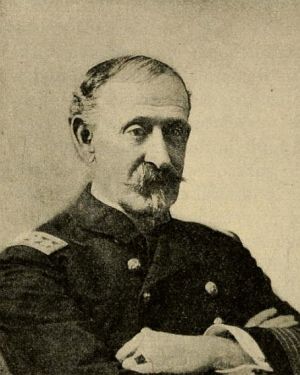

| 658-670. | The War with Spain | 515 |

| 671-676. | Consequences of the War | 524 |

| 677-681. | The Close of McKinley’s First Administration | 527 |

| 682-683. | McKinley’s Second Administration | 531 |

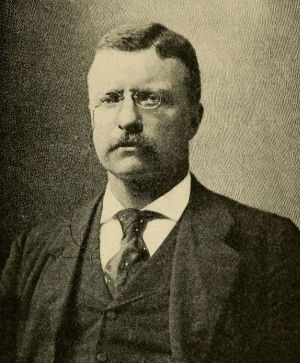

| 684-701. | Roosevelt’s Administration | 532 |

| References | 550 | |

| CHAPTER XXXIX.—PROGRESS OF THE EPOCH. | ||

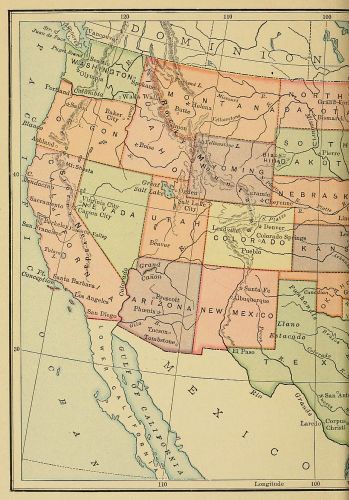

| 702-705. | Spread and Character of the Population | 551 |

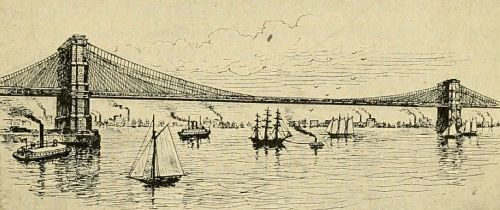

| 706-709. | National Development | 553 |

| APPENDIX. | ||

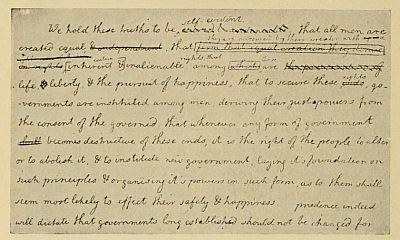

| A. Declaration of Independence | 559 | |

| B. Constitution of the United States of America | 564 | |

| Amendments to the Constitution | 575 | |

| C. List of Presidents and Vice Presidents, | ||

| with their Terms of Office | 579 | |

| INDEX | 581 | |

| 1000 (circa) | The Northmen reach America. |

| 1492 | Columbus lands at Watling’s Island. |

| 1497 | John Cabot lands near the mouth of the St. Lawrence. |

| 1498 | Voyage of Sebastian Cabot. |

| 1499–1503 | Americus Vespucius makes four voyages to America. |

| 1512 | Ponce de Leon discovers Florida. |

| 1513 | Balboa discovers the Pacific. |

| 1520 | Magellan passes the straits named after him. |

| 1541 | De Soto discovers the Mississippi River. |

| 1562–1564 | Huguenots in South Carolina and Florida. |

| 1565 | St. Augustine, Florida, founded by the Spanish. |

| 1577–1580 | Drake makes his voyage round the world. |

| 1584–1587 | Sir Walter Raleigh sends out colonists. |

| 1607 | Founding of Jamestown, Virginia. |

| 1608 | Champlain founds Quebec. |

| 1609 | Hudson discovers the Hudson River. |

| 1614 | The Dutch settle on Manhattan Island. |

| 1620 | Landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth. |

| 1626 | The Dutch found New Amsterdam (New York City). |

| 1630 | Winthrop leads Puritan emigration to Massachusetts. |

| 1630 | Boston founded. |

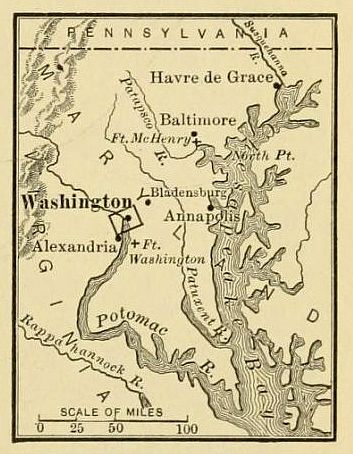

| 1632 | Charter for Maryland granted the second Lord Baltimore. |

| 1634 | St. Mary’s, Maryland, founded. |

| 1635 | Settlements made in Connecticut. |

| 1636 | Roger Williams founds Providence, Rhode Island. |

| 1636 | Harvard College founded. |

| 1638 | New Haven settled. |

| 1638 | Swedes occupy Delaware. |

| 1639 | Constitution of Connecticut framed. |

| 1643 | New England Confederacy established. |

| 1663 | Government organized in North Carolina. |

| 1664 | The English seize New Netherland and settle in New Jersey. |

| 1670 | Settlement in South Carolina. Charleston founded. |

| 1674–1676 | King Philip’s War. |

| 1676 | Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia. |

| 1682 | La Salle explores Mississippi River. |

| 1682 | Philadelphia founded. |

| 1689–1697 | King William’s War. |

| 1690 | Colonial Congress at New York. |

| 1692 | Salem witchcraft. |

| 1692 | William and Mary College (Virginia) founded. |

| 1697 | Peace of Ryswick. |

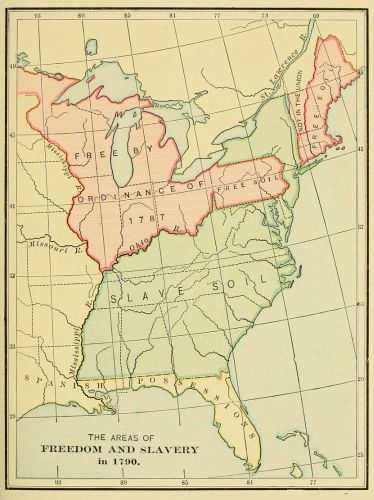

| 1701 | Detroit founded. |

| 1701 | Yale College founded. |

| 1702–1703 | Queen Anne’s War. |

| 1713 | Treaty of Utrecht. |

| 1718 | The French found New Orleans. |

| 1730 | Baltimore founded. |

| 1733 | Savannah founded. |

| 1744–1748 | King George’s War. |

| 1745 | Capture of Louisburg. |

| 1746 | Princeton College founded. |

| 1748 | Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. |

| 1754 | King’s (Columbia) College founded. |

| 1754 | French and Indian War begins (ends 1763). |

| 1755 | Braddock’s defeat. |

| 1759 | Capture of Quebec. |

| 1763 | Peace of Paris. |

| 1763 | The Conspiracy of Pontiac. |

| 1765 | The Stamp Act passed. |

| 1766 | Repeal of Stamp Act. |

| 1767 | Townshend Acts. |

| 1768 | British troops in Boston. |

| 1770 | Boston Massacre. |

| 1773 | “Boston Tea-party.” |

| 1774 | Boston Port Bill. |

| 1774 | First Continental Congress meets in Philadelphia. |

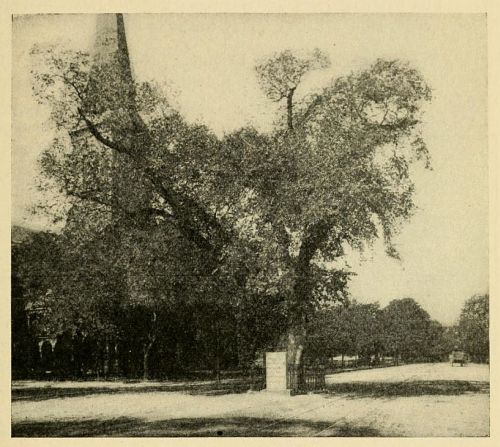

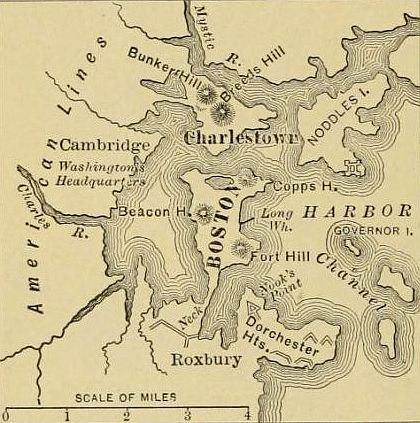

| 1775 | Battles of Lexington and Concord. Siege of Boston. Battle of Bunker Hill. |

| 1775 | Mecklenburg Resolutions. |

| 1776 | Declaration of Independence. |

| 1777 | Victories of Princeton, Bennington, and Saratoga. Defeats of Brandywine and Germantown. Washington at Valley Forge. |

| 1778 | France becomes an ally of the United States. |

| 1779 | Naval victories of Paul Jones. |

| 1780 | Arnold’s treason. |

| 1781 | Articles of Confederation finally agreed to. |

| 1781 | Battle of Cowpens. Cornwallis surrenders at Yorktown. |

| 1782 | Preliminary treaty with Great Britain. |

| 1783 | Peace of Versailles. |

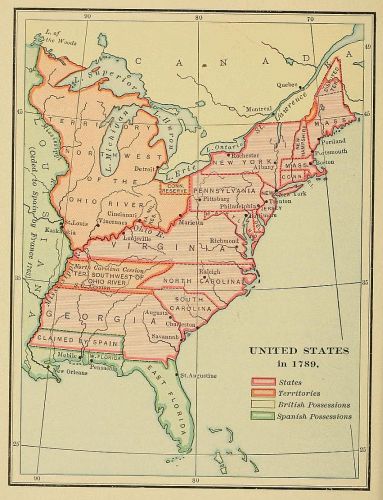

| 1787 | Federal Convention frames the Constitution. |

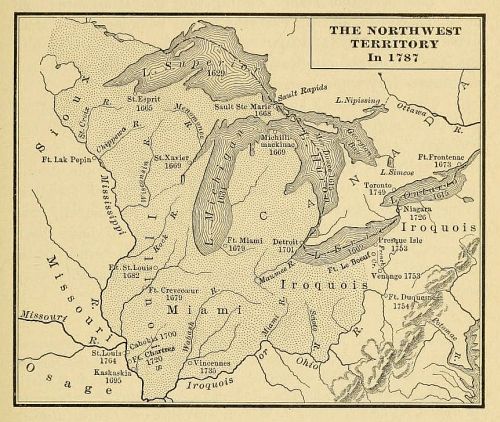

| 1787 | Ordinance concerning the Northwest Territory passed by Congress. |

| 1788 | The states ratify the Constitution. |

| 1789 | Washington inaugurated at New York. Organization of Congress and the Departments. |

| 1792 | Formation of Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties. |

| 1793 | Washington’s proclamation of neutrality. |

| 1795 | Jay’s Treaty ratified. |

| 1798 | The Alien and Sedition Laws. |

| 1798 | The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. |

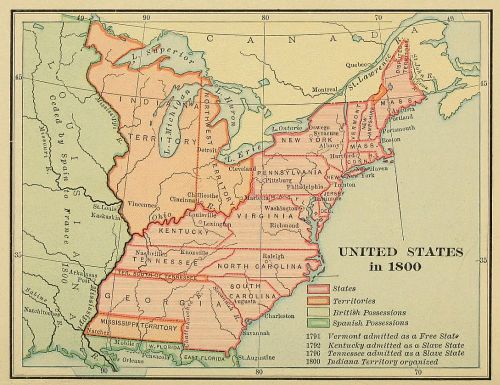

| 1800 | The city of Washington becomes the national capital. |

| 1801 | Jefferson elected President by the House of Representatives. |

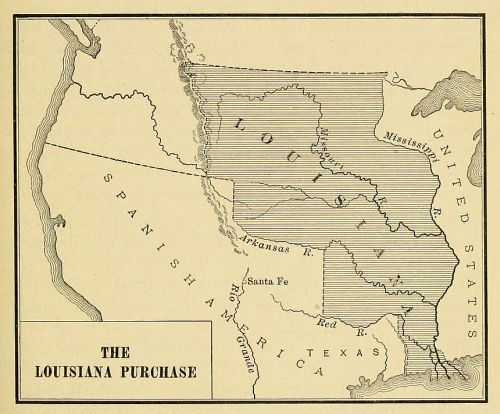

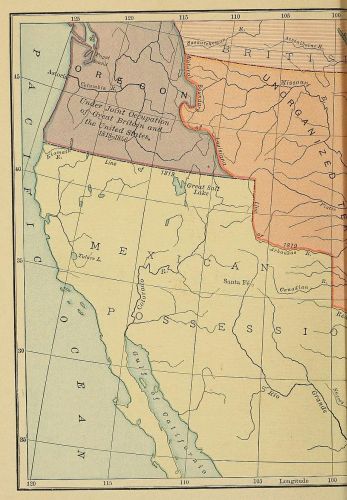

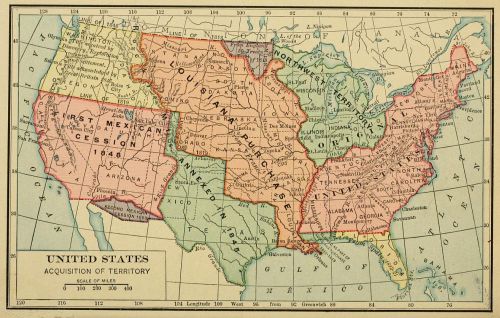

| 1803 | Purchase of Louisiana. |

| 1804 | Expedition of Lewis and Clark. |

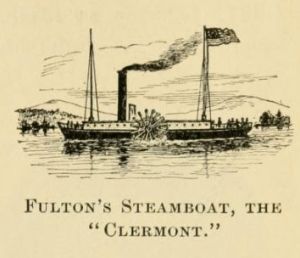

| 1807 | Fulton’s steamboat. |

| 1807 | Passage of the Embargo. |

| 1809 | The Non-intercourse Act. |

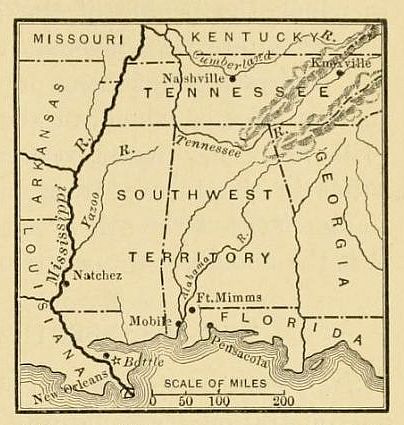

| 1812 | War with Great Britain. |

| 1814 | The British capture Washington. |

| 1814 | The Hartford Convention. |

| 1814 | The Treaty of Ghent. |

| 1815 | The battle of New Orleans. |

| 1819 | Florida purchased from Spain. |

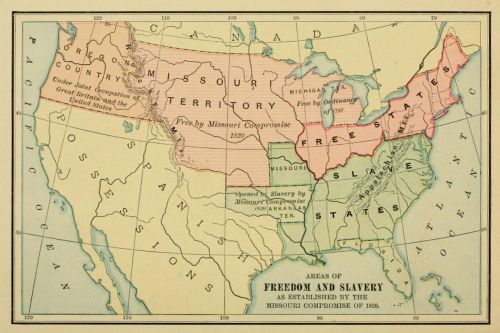

| 1820 | First Missouri Compromise. |

| 1823 | Monroe Doctrine. |

| 1825 | Erie Canal opened. |

| 1830 | Hayne-Webster debate. |

| 1830 | Baltimore and Ohio Railroad opened. |

| 1832 | Nullification in South Carolina. |

| 1832 | Rise of the Whig party. |

| 1833 | Chicago founded. |

| 1836 | Independence of Texas. |

| 1840 | Sub-treasury system established. |

| 1840 | Liberty party formed. |

| 1842 | Ashburton Treaty. |

| 1842 | Dorr’s Rebellion in Rhode Island. |

| 1844 | Morse completes the first telegraph line. |

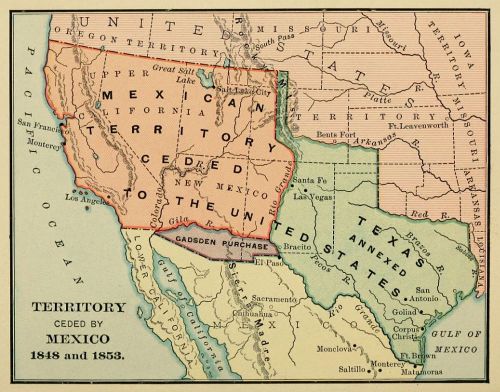

| 1846–1848 | Mexican War. |

| 1846 | Wilmot Proviso. |

| 1846 | Oregon Treaty. |

| 1848 | Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. |

| 1848 | Discovery of gold in California. |

| 1850 | Compromise of 1850. |

| 1850 | Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. |

| 1852 | Rise of Know-Nothing party. |

| 1853 | Gadsden Purchase. |

| 1854 | Kansas-Nebraska Bill. |

| 1854 | Republican party formed. |

| 1855 | Struggle in Kansas. |

| 1857 | Dred Scott Decision. |

| 1858 | First Atlantic cable. |

| 1858 | Lincoln-Douglas debates. |

| 1859 | John Brown’s raid. |

| 1860 | Election of Lincoln. Secession of South Carolina. |

| 1861–1865 | The Civil War. |

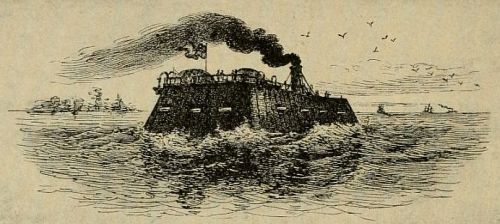

| 1862 | Fight between Merrimac and Monitor. |

| 1863 | Proclamation of Emancipation. |

| 1863 | Battle of Gettysburg. Capture of Vicksburg. |

| 1864 | Battle of the Wilderness. |

| 1865 | Surrender of Lee and Johnson. |

| 1865 | Assassination of Lincoln. |

| 1866 | Successful laying of the Atlantic cable. |

| 1867 | Congressional system of reconstruction. |

| 1867 | Purchase of Alaska. |

| 1868 | Impeachment of President Johnson. |

| 1869 | Completion of the Pacific Railroad. |

| 1871 | Treaty of Washington. |

| 1876 | Electoral Commission. |

| 1877 | Troops withdrawn from the South. |

| 1879 | Resumption of specie payments. |

| 1883 | Civil Service Reform Commission. |

| 1892 | Rise of People’s Party. |

| 1898 | War declared with Spain. Treaty of Paris. Acquisition of the Philippines. |

| 1898 | Annexation of Hawaii. |

| 1901 | Hay-Pauncefote Treaty. |

| 1902 | Panama Canal authorized. |

| 1905 | Treaty of Portsmouth. |

| 1907 | Financial crisis. |

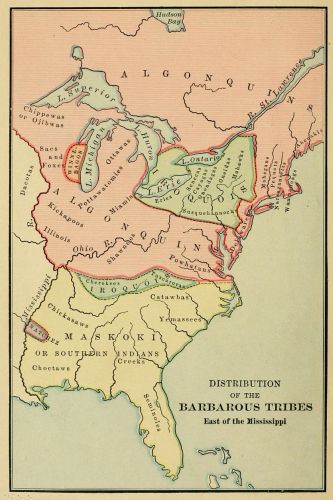

Distribution of the Barbarous Tribes

East of the Mississippi

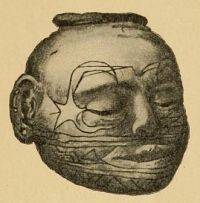

Specimen of Indian Pottery,

from a mound near Pecan Point,

Arkansas. Now in the National

Museum at Washington.

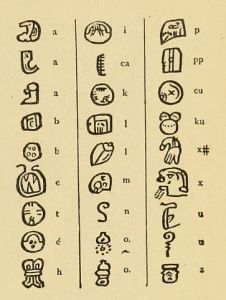

Diego de Landa’s Maya

Alphabet.

1. The Aborigines.—When America became known to Europe at the end of the fifteenth century, it was by no means an uninhabited country. Wherever the discoverers effected a landing, and however far they pushed inland, they found themselves confronted by native inhabitants of varying degrees of savagery. Hence the settlement of both Americas, from first to last, has been dependent upon the supplanting of one race by another or upon their intermixture.

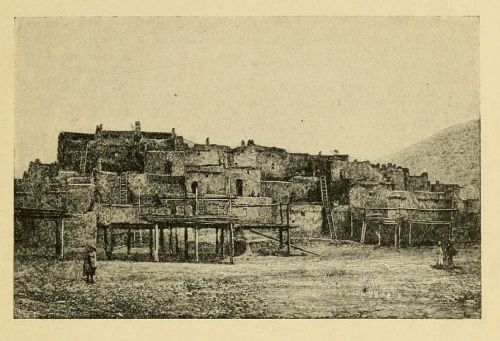

2. Characteristics of the Indians.—The original inhabitants of both continents have been known as Indians, in consequence of a mistake made by Columbus (§§ 5-7). The North American Indians were fiercer foes than the native Mexicans and Peruvians whom the Spaniards, under Cortez and Pizarro, overcame, and with whom they intermarried. We know, however, from linguistic characteristics, that all the aborigines from the Arctic Circle to Cape Horn belonged to the same race. How they first came to America is a matter of dispute; but their main peculiarities are well understood. In Peru and Mexico they had made some progress toward civilization. They constructed good roads, were not unskillful artisans, and had even learned some astronomy. But they lived in large communal groups under their chiefs, and had made slight advance in the art of government; hence they fell an easy prey to small bodies of Spaniards. Similar in character to the Mexicans, but inferior to them, were the Pueblos and Cliff-dwellers of the region of New Mexico, Arizona, and Lower California, as well as the Natchez Indians of the Lower Mississippi Valley. Most of the North American Indian tribes lived in villages of wigwams and had a primitive form of government. In each village there was a communal, or “long,” house, in which clan business was transacted. In a few cases this “long” house gave shelter to a whole tribe. These Indians, except among the Southern tribes mentioned below, were chiefly in what is called the hunter and fisher state, although they frequently practiced a rude form of agriculture. Sometimes, however, as in the case of the Digger Indians, they subsisted mainly on roots.[1]

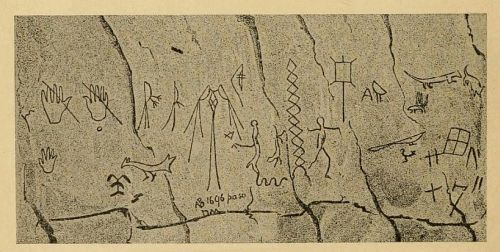

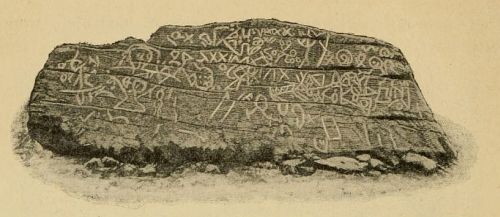

Inscription Rock, New Mexico.

3. The Principal Indian Tribes.—Of the North American Indians with whom our own forefathers came chiefly in contact, there were four principal groups, commonly known as the Algonquins, the Iroquois, the Southern Indians, and the Dakotahs. The Algonquins were the most numerous, although it is doubtful if at any time they numbered ninety thousand. Ranging through the vast forests from Kentucky to Hudson Bay and from the Mississippi to the Atlantic, they were naturally in frequent conflict with the whites. Opposed to these, and wedged into the very center of their territory, were the fierce Iroquois, the craftiest of their race, whose tribal names—Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas—are inseparably connected with rivers and lakes in the State of New York. They formed a loose confederacy, called by the whites the “Five Nations.”[2] The Southern Indians showed a milder disposition and were given to agriculture and rude manufactures. Of these the Creeks were the most advanced; beneath them in point of civilization were the Cherokees, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Seminoles.[3] West of the Mississippi ranged the wandering Dakotahs or Sioux, fierce fighters, whose descendants have given trouble down to our own day. Of the inferior tribes living in the extreme north of the continent, we need take no special account.

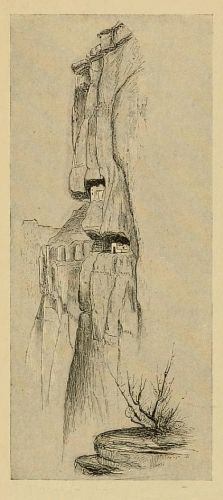

Cliff Dwellings on the

Rio Mancos.

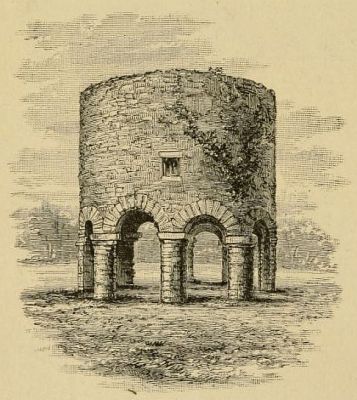

Old Mill at Newport, long

erroneously supposed to have been

built by the Northmen.

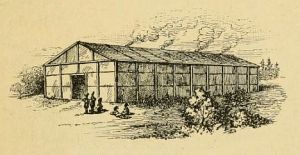

Long House of the Iroquois.

4. The Northmen.—While Columbus and his followers were the real discoverers of America in the sense that they first made it generally known to Europe, it is practically certain that they were not the first Europeans to set foot on the new continent. It is possible that seamen from France and England preceded Columbus, but there is much better reason to believe that Scandinavians from Iceland, having first discovered Greenland, visited the North American mainland as early as the year 1000. Evidence to this effect is found in the so-called Sagas of the Northmen, poetic chronicles based on tradition and dating from about two centuries after the events which they recorded. According to these stories, navigators were driven south from Greenland to a strange shore about the year 985. Fourteen years later, Leif, son of Eric the Red, having introduced Christianity from Norway into Iceland and Greenland, visited the newly discovered land, with thirty-five companions. They wintered in a country which, from its abundance of wild grape vines, they called Vinland, built some houses, and then returned to Greenland with a cargo of timber. Several other voyages were made thither and a temporary colony was established, the latest mention of a voyage dating from about the middle of the fourteenth century. Such is the story of the Sagas. The main features of the account are generally held to be correct, but the location of the Northmen’s Vinland cannot be determined, and no archæological remains have been found on the American continent to corroborate the Sagas.[4]

North Pueblo of Taos.

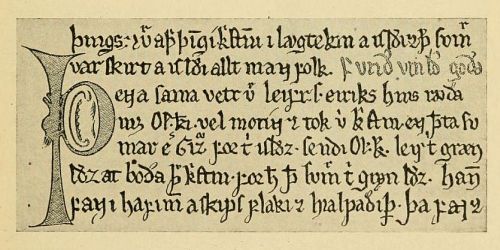

Specimen of Saga Manuscript.

The Dighton Rock in Massachusetts,

long supposed to bear an inscription left by the Northmen.

The figures are now known to be Indian hieroglyphics.

Columbus.[6]

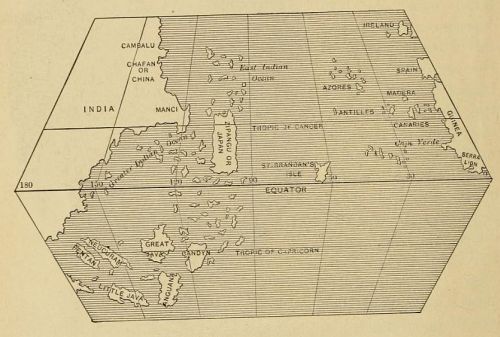

5. Columbus and the Indies.—That Christopher Columbus[5] of Genoa is entitled to the honor of being considered the real discoverer of America is clearly proved by the fact that he was the first person who planned to sail westward over the unknown ocean, and that he never faltered in the prosecution of his heroic design. It is true that he made the mistake of thinking he would come to India rather than to a new continent, and that he underestimated the distance he would have to sail; but such mistakes were natural in view of the lack of geographical knowledge at that time. It was generally believed, by priest and layman alike, that the earth was flat, and good Scripture warrant was produced for the belief. Yet since the days of Aristotle a few scholars had concluded, from the evidences furnished by eclipses and from other reasons, that the earth was spherical in form. Columbus had obtained this idea from some source and seems to have been fascinated by the possibilities it opened. Oriental commerce, especially that from India, was then of great consequence to Italian merchants; and if the recent military successes of the Turks should close the overland routes to the East, it was thought this commerce would be destroyed. But Columbus held that, if the earth were round, India could be reached by sailing westward, and thus trade could be carried on in spite of the Turks.

Toscanelli’s Map (simplified)

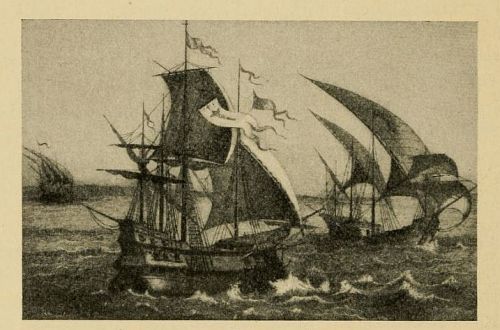

6. Motives and Difficulties of Columbus.—Columbus was urged on by patriotism, desire of gain, missionary hopes of Christianizing distant lands, and a natural enthusiasm for heroic enterprise. He corresponded with Toscanelli, a learned Italian, who sent him letters and a map, but underestimated greatly the distance to be traversed. This mistake was fortunate, as Columbus would probably never have secured a hearing had he proposed to take a voyage of ten thousand miles,—the actual distance between Spain and the East Indies. As it was, for a long time he applied in vain to princes and potentates—who alone could sustain the expenses of such an expedition—for permission and means to make a voyage which he believed to be about three thousand miles in length. The record of his hopes and fears, his successes and reverses, reads like a heroic poem. Fortunately for him, the Portuguese had been making voyages down the African coast, with their eyes fixed on the Eastern trade, and the Spaniards, strong through the recent union of Castile and Aragon and the conquest of the Moorish kingdom of Granada, had been aroused to eager rivalry in maritime enterprise. At the court of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Spanish monarchs, Columbus eloquently pleaded his cause. Success at last crowned his efforts. Under the patronage of Isabella he sailed from the port of Palos, with a fleet of three vessels, on the 3d of August, 1492.

Ships of the Time of Columbus.

7. Voyages of Columbus.—Within a month the adventurers had left the Canaries and were traversing the unknown ocean. As the days went by the crews became restless, but the dauntless resolution of Columbus prevented mutiny. Finally, after a fortunate change of course to the southwest, the great navigator saw a light ahead, on the evening of October 11, and the following morning he found that an island had been reached. It was probably Watling’s Island, one of the Bahama group, though the identity of the landing place has been a matter of much dispute.[7] On this first voyage Columbus coasted along the northern side of Cuba, and also discovered the island now known as Hayti. Then, after losing his largest ship and suffering many other trials, he returned to Spain, confident that he had reached islands off the coast of India. The Spanish sovereigns received him with great respect and pomp, and soon sent him back to take possession of his discoveries in the name of Spain. Unfortunately, there was little or no wealth to be obtained from the new possessions except by capable colonists, and Columbus was not fitted to govern dependencies. So great did the opposition to him become that he was arrested some years later, on account of charges of extortion and cruelty brought by his followers, and was sent to Spain in irons. He was soon released, however, and undertook his fourth and last voyage. The results of his last three expeditions were not important. He succeeded in exploring more of Cuba, and in discovering Jamaica. He reached also the mouth of the Orinoco, and was much puzzled to account for its size, which was too great for an island river. On his last voyage he coasted the shores of Central America, in a vain search for a waterway to India. He found no strait, but did find an isthmus; and when he heard reports of a vast body of water lying on the other side of the land, he thought that it must be the Indian Ocean. Thus he was confirmed in his error with regard to the nearness of India, and doubtless cherished his delusion to his death. After his fourth voyage he returned to Spain, and died there in 1506, in poverty and obscurity.

Sebastian Cabot.

8. The Cabots and the English Title.—Almost immediately after Columbus’s first voyage, Pope Alexander VI. issued a bull dividing the non-Christian portion of the world into two parts: Spain to have all that she might discover west of a line to be drawn one hundred leagues west of the Azores; and Portugal all that she might discover east of it. In the following year the rival nations fixed the line at three hundred and seventy leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Aroused by these events, Henry VII. of England, who was laying the foundations of Tudor greatness, granted a license of exploration to John Cabot, an Italian then living in Bristol. This seaman landed somewhere near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, in 1497. Accounts of the voyage are unsatisfactory; and those of the voyage of 1498, supposed to have been made under the command of Cabot’s son Sebastian,[8] are still more vague. That the Cabots did make northerly discoveries on which the English based their right to colonize North America is, however, quite certain.

9. Other Successors of Columbus.—The discovery of the West Indies, as the new islands were named in consequence of Columbus’s mistake, naturally gave a great impetus to exploration. In 1497–98 the Portuguese under Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and reached the real India, the goal of their desires. In the last year of the same century another Portuguese, Gaspar Cortereal, explored a good deal of the North American coast, and in a few years Newfoundland was much frequented by fishermen, especially from France and England.[9] Little was known, however, about the geography of the new world. Many strange errors were current respecting it, and some years passed before it was given a name. One of the errors was that North America was a projection of Asia, which was not disproved until 1728, when the Russian navigator Vitus Bering sailed from the Pacific into the Arctic Ocean. This error had much to do with the delay in furnishing the two continents with names. By a curious chain of circumstances, too, the name finally settled upon did not do honor to Columbus.

Americus Vespucius.

10. The Name “America.”—Among the early successors of this great explorer was another Italian, Amerigo Vespucci, or, in the Latin form then current, Americas Vespucius.[10] Little is known of him or his voyages, but it is clear that he was one of the first Europeans after Columbus to visit the northern coast of South America, and that in 1504 he wrote an account of his adventures. This account circulated as far as the college town of St. Dié in the Vosges Mountains, and was there printed with an introduction by one of the professors, Martin Waldseemüller by name, who proposed that, since now a fourth division of the earth’s inhabited surface must be named, this should be known as America, in honor of Americus Vespucius, who was supposed to have discovered it. There appears to have been no intention to slight Columbus, whose voyage to the Orinoco was probably not widely known. At any rate, the suggestion was followed, first as regards South America, later with regard to both continents.

Balboa.

11. Balboa’s Discovery of the Pacific.—Geographical knowledge was much advanced by the discovery of the Pacific Ocean by Vasco Nuñez de Balboa[11] in 1513. This brave Spaniard had sought the New World for the sake of wealth, but had met with many difficulties. Lured by tales told by the natives of Panama of a large ocean and lands abounding in gold beyond the mountains, he made his way to the top of the Cordilleras, and thence beheld a great sea to the south of him, which he called the South Sea, a name long retained by English writers. It is the irony of fate that in the best-known reference in English literature to this discovery,—in the famous sonnet by Keats,—the honor of making it should have been transferred to Cortez, who had celebrity enough of his own.

Magellan.

12. The Voyage of Magellan.—The name Pacific was given to the great ocean by the most glorious of Columbus’s successors, the Portuguese Fernãdo de Magalhães,[12] better known as Magellan. In 1519, while in the service of Spain, he followed the coast of South America, hoping to find a strait that might lead into the South Sea. Late in the next year he discovered the strait that bears his name, and sailed into the great ocean to which he gave the name Pacific, on account of its peaceful character. This name was ironical so far as his own career was concerned; for one of his five crews mutinied, one ship was cast away and another abandoned him, and he himself was killed in an encounter with the natives of the Philippine Islands. But he had won a glorious immortality, although it was really the survivors of his crews that finally made their way around the Cape of Good Hope and completed the first circumnavigation of the globe.

Ponce de Leon.

De Soto.

13. Spanish Conquests.—Meanwhile a Spaniard, Ponce de Leon,[13] had discovered Florida in 1512 and had found the perfect climate, but not the gold and silver and fountain of youth he sought. His attempt nine years later to establish a colony there was a complete failure. Success attended, however, the expedition of Hernando Cortez for the conquest of Mexico (1519–1521), and similar good fortune befell that of Francisco Pizarro for the subversion of Peru (1532). The New World was rapidly alluring the Spaniards, who made many explorations. For example, Cabeza de Vaca, an officer in Panfilo de Narvaez’s unfortunate expedition to the Gulf coast, wandered in the interior regions a long while, and finally emerged on the Mexican border, with marvelous tales of what he had seen and heard (1536). These tales caused the Viceroy of Mexico, Mendoza, to send a certain friar to investigate them; and, upon the facts and the numerous errors contained in the friar’s report, hopes were founded that induced the sending out of a large force under Francisco Vasquez Coronado (1540–1542). This expedition conquered many pueblo villages of the Southwest, but obtained no gold or silver, and, after struggling as far north as Kansas, ended in a disconsolate retreat. At about the same time another expedition was moving westward from Florida through the Gulf region, under the command of Hernando de Soto (1539–1542). This gallant man pushed northwest across the mountains and discovered the Tennessee River, and later the Mississippi; but he died soon after, and his followers abandoned their enterprise. Thus by the middle of the century no permanent Spanish settlement had been made in what is now the United States. Nor was Spain long to have things her own way.

Jacques Cartier.

14. French Discoveries.—As we have seen, French fishermen were among the first to reach Newfoundland. A little later the voyage of Giovanni da Verrazano, a native of Florence, under commission of Francis I., showed the dawning interest in the New World taken by the French court. In 1524 Verrazano explored much of the Northern coast as far as Newfoundland. In 1534 and 1535 Jacques Cartier[14] discovered Prince Edward Island, sailed up the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and penetrated the great river as far as the present site of Montreal, fancying most of the time that he was rapidly nearing China.[15] A few years later he came again, bringing colonists with him; but the enterprise did not succeed, and in consequence was soon abandoned.

15. Arrival of Huguenots.—France was now torn with civil and religious discord, and, as a result, Admiral Coligny, the great leader of the Huguenots, determined to found a place of refuge for his co-religionists in a more tempting part of America than Canada. Accordingly, in 1562, Jean Ribaut, under his orders, sailed for the Southern coast and discovered the present St. John’s River in Florida. He left a small colony on Port Royal Sound, but it was soon scattered. Two years later, René de Laudonnière established another settlement on the St. John’s, but the colonists were disorderly. Some of them mutinied and attempted to plunder the Spaniards in the West Indies. Learning thus of the existence of the French settlement, the Spaniards under Menendez organized a strong expedition against it. The French had meanwhile been reënforced by a fleet under Ribaut and by Sir John Hawkins, the English slave-trader and famous fighter. But in spite of these reënforcements the French did not use their opportunities, and their vessels were soon scattered by a storm. Then Menendez, who had just established himself at St. Augustine (1565), destroyed the French fort and killed or captured nearly all the Frenchmen at that time in Florida. St. Augustine, the oldest town in the United States, still stands to record this savage warfare. A little later a French soldier, Dominic de Gourges, partly avenged his countrymen; but St. Augustine was not taken, and the French crown relinquished all claims to Florida.

Champlain.

16. Champlain.—In the progressive reign of Henry IV. of France, attention was once more paid to Canada. After a colony had failed on the Isle of Sable, near Nova Scotia, and another had all but come to grief in Nova Scotia proper, Samuel de Champlain[16] succeeded in establishing a permanent post at Quebec in 1608. In a few years, owing to the zeal of the Jesuit missionaries and the enterprise of the fur-traders, the French had obtained a firm grip upon Canada and were rapidly pushing inland.

Sir Francis Drake.

17. English Explorations during the Reign of Elizabeth.—The English, unlike the French, were at first content with their fisheries in Newfoundland; and it was not until after 1570 that they seriously took part in the affairs of America. Their tardiness was probably at first due to the marriage of Henry VIII. with a Spanish princess, then to their own internal troubles in consequence of the Pope’s condemnation of Henry’s conduct. Finally, in the reign of Elizabeth, a love of geographical knowledge and discovery having sprung up, they turned their attention to exploring for a northwest passage to the East. Martin Frobisher made three voyages (1576–1578), and sought gold in Labrador. Francis Drake,[17] in his voyage round the world (1577–1580), explored part of the Pacific coast of the present United States. Sir Humphrey Gilbert and his half-brother, Sir Walter Raleigh,[18] wished to colonize as well as explore, and after one disastrous attempt Gilbert took possession of Newfoundland in the name of Queen Elizabeth. He was lost on the return voyage, but left behind him an undying reputation for courage and piety.[19]

Sir Walter Raleigh.

18. Raleigh’s Colonies.—Raleigh continued the work of Gilbert by organizing expeditions, in which he took, however, no personal part. The first exploration was made in 1584 by Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe. These two leaders visited the coast of North Carolina, and returned bringing favorable accounts of the region, which was named Virginia, after the Virgin Queen. The next year Raleigh fitted out seven ships, and a colony was established on Roanoke Island. This in spite of several reënforcements finally proved a failure, the last colonists having disappeared in a manner never accounted for.[20] Meanwhile the defeat of the Spanish Armada off the coast of England had rendered it quite certain that with England’s sea power established, she would be able to colonize the northern parts of America without great fear of molestation.

19. Colonization in the Sixteenth Century.—As we have just seen, Spain, France, and England made many efforts during the sixteenth century to obtain permanent possessions in the New World. Spain succeeded in Mexico and Peru, and made a mere beginning in Florida. France did not really get a foothold in Canada until the first decade of the next century, and this was likewise the case with the English in Virginia. All three nations had too many things to disturb them at home to be able to put forth their full strength in establishing their claims to the new country. The work of exploration in consequence was hazardous and slow. Then, again, the precise value of the possessions they were striving for was not understood. Men chiefly sought the precious metals, and in the race for these Spain came off victor. But to obtain them she sacrificed the lives of the helpless natives and of imported negro slaves, and thus never laid the foundations for successful, thriving colonies. She injured herself, too, by accustoming her own people to the idea that the mother country ought to be supported by her colonies, and that labor was beneath a Spaniard of good blood.

20. Changes in the Theory of Colonization.—France and England, also, sought for gold and silver, but found none. The lands they occupied could be made productive, but not by the ne’er-do-well adventurers who first came out. When, however, fish and furs, and, later on, tobacco, became far more profitable than the metals would have been, the character of both English and French colonists gradually improved. The value of the new possessions was not to be perceived fully, however, until the eighteenth century, when they played a part in all the important European wars. Nor even then did statesmen at home realize that the mother country’s interests were best served by keeping her colonists prosperous. A colony was at first viewed merely as a source of revenue, and in some cases even as a dumping-ground for criminals. It is only of late that colonies have figured as outlets for superfluous population and as bases for extending commercial operations.

References.—General Works which should be consulted in connection with each of the five chapters of Part I. are: J. Winsor, Narrative and Critical History of America (contains special monographs of great value); G. Bancroft, History of the United States (revised edition); R. Hildreth, History of the United States; J. A. Doyle, The English in America; R. G. Thwaites, The Colonies, chaps. i.–iii. (“Epochs of American History”); G. P. Fisher, The Colonial Era (“American History Series”).

Special Works: J. Fiske, Discovery of America; E. J. Payne, History of the New World called America; W. H. Prescott, Conquest of Mexico and Conquest of Peru; E. Eggleston, The Beginners of a Nation; J. Winsor, Christopher Columbus; also biographies of Columbus by Washington Irving, C. K. Adams, and C. R. Markham; W. Irving, Companions of Columbus; A. Helps, Spanish Conquest of America; F. Parkman, Pioneers of France; J. Winsor, From Cartier to Frontenac; E. J. Payne, Voyages of the Elizabethan Seamen (also various biographies of Drake, Raleigh, etc.); H. H. Bancroft, The Pacific States, Vol. XVIII.

On the Indians, see Fiske and Payne, as above, and the writings of L. H. Morgan and A. F. Bandelier. For full bibliographies, consult Channing and Hart’s Guide to American History. For illustrative material, consult Old South Leaflets and Hart’s American History told by Contemporaries. The first voyage of Columbus is described in Cooper’s Mercedes of Castile; Elizabethan maritime enterprise, in C. Kingsley’s Westward Ho!

|

For a brief but scientific account of the chief characteristics of the aborigines, see article, “Indians,” by D. G. Brinton and J. W. Powell, in Johnson’s Universal Cyclopædia. |

|

“Seminoles” means “wanderers”; the tribe was made up of refugees from other tribes, notably from the Creeks. |

|

No portrait of Columbus has any claim to authenticity. There is no evidence that his likeness was drawn or painted by anyone who ever saw him. |

|

Born about 1474, in Venice or Bristol. Probably accompanied his father John in the latter’s first voyage to America in 1497, and succeeded him in command of the second expedition, in 1498. |

|

In consequence of these discoveries fishing rights on the island have been held by the French to our day. |

|

It is an interesting fact that the first English child born on American soil was Virginia Dare, granddaughter of John White, governor of this colony. |

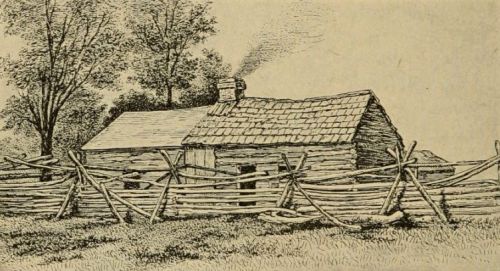

21. The Virginia Company.—At the beginning of the seventeenth century England undertook in earnest to plant colonies in North America. Her only important rival was France. Efforts were first directed toward the vast unoccupied stretch of country between Canada and Florida. The upper part of this region was explored, with favorable results, by Bartholomew Gosnold in 1602, by Martin Pring in 1603, and by George Weymouth in 1605. These enterprises were encouraged by the new king, James I., and Raleigh was soon out of favor. The work of colonization required coöperation; and the example of the Muscovite and East India companies led certain important citizens to obtain a charter authorizing them, as the Virginia Company, to promote and govern colonies in the unsettled region. It was a favorable time for such an undertaking, since changes in agricultural methods and other economic causes had created a spirit of unrest and filled England with men eager for employment. Besides, the passion for discovery and the energy that marked Elizabeth’s reign had by no means died out, and fortune seemed beckoning from the new shores.

22. The Sub-companies.—The Virginia Company’s charter covered a region extending from the thirty-fourth to the forty-fifth degree of north latitude. This was not to be controlled by one set of men, however, for there were two sub-companies, one consisting of the charter members living in or near London, and the other of those living in or near Plymouth. The Londoners could colonize from the thirty-fourth to the thirty-eighth degree; the Plymouth people from the forty-first to the forty-fifth, while the intervening space was left to whichever company should first colonize it, with the proviso that neither company should settle within one hundred miles of the other. This idea of competition between the companies led to nothing, and indeed the whole scheme of the charter was a cumbrous one that promised little permanent success.

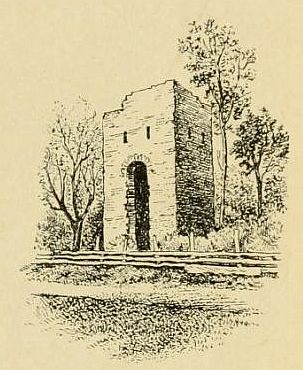

Ruins of the Old

Church at Jamestown.

23. The Settlement at Jamestown.—In 1607 both sub-companies began operations. The Plymouth men sent a fleet to the coast of the present state of Maine, but the colony they tried to plant was a failure. The London Company was more fortunate. Their colonists reached Chesapeake Bay in the spring, and settled about fifty miles above the mouth of a large river, since then known as the James, in honor of the English king. They called their new settlement Jamestown, and at once began to build huts and fortifications.

24. Captain John Smith.[21]—Their leading spirit was Captain John Smith, an adventurous and able man, who in spite of jealousies put himself at the head of affairs and saved the colony. The men sent out were mainly gentlemen adventurers seeking to mend their fortunes, and even some of the real workers followed callings not required in the wilderness. There was consequently much bickering, and soon a scarcity of provisions caused great suffering. The site of the town proved unhealthy, and the Indians encountered had to be watched. Altogether the situation was a wretched one, and but for the energy of Smith and a few others, Christopher Newport, the captain of the fleet, who had gone back to England for supplies, might have found few vestiges of a settlement on his return in 1609. Newport brought stores, but also a number of undesirable colonists. He speedily sailed back to England with a cargo of shining earth, which did not yield the gold it promised to credulous eyes. Smith besought the Company to send out good workmen to cultivate the rich soil; and after a while the promoters of the colony learned not to expect vast discoveries of gold and silver. In October, 1609, owing to an accident to his eyes, Smith left the colony, never to return.

John Smith.

25. Smith’s Character.—Smith’s relations with Virginia have been the subject of much hostile criticism. Discrepancies have been found between his earlier and his later accounts of his exploits, and some historians have been led to regard him as little more than a braggart. This is an untenable view. His management of the refractory colonists, his dealings with the Indian chief Powhatan, his wise and manly remonstrances with the London Company,—all go to show that he was an able and unselfish leader to whom the life of the struggling settlement was mainly due. On the other hand, there can be little doubt, save in the minds of his partisans, that he frequently embellished his accounts of his adventures, and that he is not the most reliable of historians. It is not at all impossible that he was really saved by Pocahontas,[22] yet the story may be as mythical as the coat of arms granted to him by the king of Hungary.

Pocahontas.

26. Annulling of the Virginia Company’s Charter.—In 1609, the year of Smith’s departure, King James gave the Virginia Company a new charter, which defined the limits of its territory in a very vague way and increased its power over its colonists. In 1612 he gave another charter, which took in the Bermuda Islands and allowed the shareholders of the Company to hold general meetings in London. Twelve years later, when the king’s Puritan opponents had got control of these meetings and used them for political purposes, he caused the charter to be annulled by a decree of court, which was a legal though not a justifiable act. The records of the Company were preserved in a romantic way,[23] and are now in the possession of the government at Washington.

27. Growth of Virginia.—Meanwhile the colony had had various ups and downs under several governors,—Lord Delaware, Sir Thomas Dale, the tyrannical Samuel Argall, Sir George Yeardley, and Sir Francis Wyatt,—but had on the whole become firmly established. Dale was strict, but successful in controlling the rougher elements; he also encouraged the policy of allowing settlers to become individual proprietors of land. Argall was speedily recalled for his misconduct. Liberal sentiments then prevailed in the colony, and its inhabitants were allowed, during Yeardley’s administration, to hold a yearly representative assembly, or legislature (1619), the first of its kind in America. This long step toward self-government, together with the increasing importance of the tobacco crop, gave Virginia a decided impetus, which the contemporaneous introduction of slavery, in the persons of twenty blacks landed and sold at Jamestown by a Dutch ship in 1619, did not at first affect. The presence of white slaves in the persons of indentured servants—a class recruited from convicts, vagabonds, and kidnapped children—produced some confusion. But colonists of position and means soon began to exert an influence opposed to disorder, and through Sir Francis Wyatt the Company promised to stand by its grant of free institutions.

28. Charles I. and the Virginia Burgesses.—In 1622 the colonists endured a loss of three hundred settlers, from an attack by the Indians whom they had maltreated. The collapse of the Company (1624) made Virginia a crown colony, dependent on the king, who was succeeded the next year (1625) by his son, Charles I. Charles, needing money in order to be able to govern without his Parliament, tried to get a profit out of a monopoly of the tobacco trade, but the colonial assembly, or Burgesses, as they were called, withstood him (1629). The convening of this assembly to discuss such a matter was an important precedent in the government of the crown colonies; but the assembly, although it could resist the king’s demand, could not prevent a royal governor like Sir John Harvey from making himself obnoxious.[24]

Henry Hudson.

29. Hudson and New Amsterdam.—In the autumn of 1609 Henry Hudson,[25] an English seaman employed by the Dutch East India Company, sailed up the river now called by his name, as far as the site of Albany. He was searching for a northwest passage to India; he found instead a good opportunity to trade with the red men, which the Dutch afterward cultivated. By 1615 houses were built on the site of Albany and of the present New York. The fur trade of New Netherland, as the region was named, was turned over to a corporation organized for that purpose, called the New Netherland Company. Politically no steps were taken at first against the English title to the country. In 1621 the Dutch West India Company took up the rôle of the New Netherland Company, and three years later sent over a number of colonists. These settled mainly near Albany; but there were other centers of population, all of which did a thriving fur trade with the Indians.

30. Organization of the Dutch Colony.—In 1626 Peter Minuit, director for the Dutch West India Company, purchased the Island of Manhattan from the Indians for a trifling amount (about twenty-five dollars), and made the town of New Amsterdam, afterward New York, the center of government. In 1629 the Company obtained a new charter and proceeded to develop a semi-feudal system of land tenure among the colonists. Individuals, styled “Patroons” (patrons), were allowed to buy tracts of land from the Indians and to settle colonists upon them. For every colony of fifty persons the Patroon was granted a large tract for himself; and as he was given political and judicial power over his colonists, New Netherland was soon in the hands of a powerful landed aristocracy, some families of which have retained a certain prestige down to the present time.

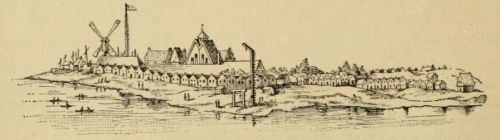

New Amsterdam.

31. The Plymouth Colony.—The London Company and the Dutch West India Company had now established promising colonies, but the Plymouth Company had done nothing since their unsuccessful attempt in 1607. Seven years later, Captain John Smith had made a voyage along the northern coast and given the region the name of New England. Other voyages added to geographical knowledge and developed the fisheries, but the more southerly colonies for some time attracted all intending settlers, and the reorganized Plymouth Company of 1620 might have fared poorly had not accident favored them. This accident was nothing less than the landing of the Pilgrim Fathers at Plymouth Rock instead of somewhere within the jurisdiction of the London Company, as they at first intended.

32. The Pilgrims in Holland.—The causes that led the Pilgrims to the New World were briefly as follows. There were large numbers of English Protestants who thought that the Established Church of England had not sufficiently broken away from the Church of Rome, especially in regard to the forms of worship. Such dissatisfied Protestants were called Puritans, and those of their number who refused to commune with the Church of England were further known as Dissenters. Those Dissenters who were ruled by elders, according to the system of Calvin and Knox, were known as Presbyterians. Such as desired each congregation to be independent were called Separatists, or Brownists, or Independents. The Pilgrim Fathers were Separatists who, in order to escape persecution, had fled from the village of Scrooby to Holland. The emigrants, headed by their pastor, John Robinson, and their elder, William Brewster, numbered about one hundred. Settling first at Amsterdam, then at Leyden, they were joined by other refugees, and lived peacefully by their labors.

33. Movement of Pilgrims to America.—These Pilgrims naturally did not wish their children to become Dutchmen; so their minds turned to America. Securing a grant of land from the London Company and financial aid from London capitalists who became partners in the enterprise, they collected their effects and sailed to their new home in the Mayflower.[26] They sighted Cape Cod on November 9, 1620. The captain, for some reason, would not sail farther southward; so after exploring the coast, the emigrants, who had already formed themselves into a body politic under a very liberal written agreement, landed at Plymouth (December 21, 1620).

34. Experiences of the Pilgrims.—Although the winter was mild, the colonists had much difficulty in obtaining shelter and food, and great loss of life was the result, Deacon John Carver, the first governor, being among the victims. William Bradford, one of the finest characters in our history, succeeded him as governor. His courage and that of his people, who believed firmly that they had the support of God, enabled the colony to pull through the crisis. Huts and a fort were built, land was cleared, and provisions and fuel laid in for the next winter. In November, 1621, fifty more of the Leyden people arrived. These were a burden to the colonists for a time, since the supply of food was small; and distribution was made, as at Jamestown, from the common stock. Settlers continued to be sent out by the London partners, but as a rule they came empty handed.

Miles Standish.

35. Success of the Pilgrims.—The colony nevertheless flourished under a patent it had obtained from the Plymouth Company. It owed much of its success to Bradford, who was often elected to the governorship, and to Captain Miles Standish, a brave soldier, not a Separatist, who was especially useful in managing the Indians. Various neighboring settlements of Englishmen who ridiculed the strict customs of the Pilgrims could not be easily dealt with; but finally the chief offenders, Thomas Morton and his associates at Merrymount, who had furnished the Indians with firearms, were put down with a stern hand. Meanwhile the communal system was abandoned for individual allotments of land. At about the same time (1627) the colonists purchased the share of the London capitalists in the enterprise.

36. Government of the Pilgrims.—They governed themselves at first by a primary assembly, then by a general court composed of two delegates from each township, elected by popular vote, together with the governor and representatives, called assistants. In 1636 a special code of laws was adopted; but on the whole the government remained as simple as were the habits of the God-fearing, thrifty people, who in many ways set an example of steadiness and perseverance to all the other colonists. It was, however, a very small settlement, and after various failures to secure its perpetuation through a royal charter, it was finally merged, in 1691, with Massachusetts[27] (§ 60).

John Endicott.

37. The Puritans and the Founding of Massachusetts.—In 1623 some merchants of Dorchester, England, sent out a colony to the coast of Maine, which for some reason was diverted to the site of the present Gloucester in Massachusetts. Three years later the colony was almost abandoned; but John White, the Puritan rector of Trinity Church, Dorchester, fearing the aggressions of the Crown in ecclesiastical matters, advised the remaining settlers to continue at Salem, whither they had migrated, and immediately laid plans in England for planting a permanent colony. Two years later a patent was obtained from the Plymouth Company for a strip of coast land, and John Endicott[28] led sixty persons to Salem. In 1629 the owners of the patent, who still lived in England, were organized as a Company and given a charter by the king. This charter provided for popular election of the governor and other officers, for a “general court,” or assembly, as well as for the passage of laws not conflicting with those of England.

John Winthrop.

38. Government of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay.—The new “Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England” was ostensibly to engage in trade, but in reality its founders intended to form a religious commonwealth. This could be easily done, since somehow or other no proviso that the Company should have its headquarters in England was inserted in the charter. Thus it was possible to transport the Company bodily to New England, and this a number of prominent Puritans, at a meeting held at Cambridge in 1629, agreed to do. There was to be no violent separation from the Established Church except such as was caused by distance; but uncongenial practices would be avoided, and the heavy hand of Archbishop Laud, then the strenuous Primate of England, would hardly reach across the sea. Thus many men of wealth and education, whose conservatism would naturally have prevented their taking rash steps in their opposition to the Crown, were led to join in the Massachusetts enterprise. In April, 1630, eleven vessels sailed for America, and by the end of the year about a thousand persons had emigrated to the new colony and founded such towns as Boston, Charlestown, and Watertown. They chose as governor a wealthy and highly educated Suffolk gentleman, John Winthrop,[29] and under his able administration the colony began a career of great prosperity and importance.

References.—General Works: To the list already given may be added: Bryant and Gay, Popular History of the United States; H. C. Lodge, Short History of the English Colonies in America; Richard Frothingham, Rise of the Republic of the United States.

Special Works: J. Fiske, Beginnings of New England; J. Fiske, Old Virginia and Her Neighbors; J. G. Palfrey, History of New England; W. B. Weeden, Economic History of New England; P. A. Bruce. Economic History of Virginia; A. Brown, Genesis of the United States; J. E. Cooke, Virginia (“American Commonwealths”); R. C. Winthrop, Life and Letters of John Winthrop; E. Eggleston, Transit of Civilization.

Standard state and colonial histories, such as Hutchinson’s Massachusetts and Belknap’s New Hampshire, may also be used, as well as biographies of colonial worthies. For documents, consult Macdonald’s Select Charters Illustrative of American History, 1606–1775. Illustrative specimens of the earliest historical writings, such as Bradford’s “History of the Plymouth Colony” and Winthrop’s “History of Massachusetts” will be found in Old South Leaflets, Hart’s American History told by Contemporaries, Stedman and Hutchinson’s Library of American Literature, and Trent and Wells’ Colonial Prose and Poetry. See Channing and Hart’s Guide. Many books relating to colonial life and manners have been published recently, but Edward Eggleston’s articles in the Century Magazine (Vols. III.–VIII.) will probably be sufficient for most purposes. Longfellow’s The Courtship of Miles Standish should be read in connection with this chapter.

|

It is worth noting that the Mayflower was not the only vessel of this expedition as it was first arranged. The companion ship, Speedwell, had an accident, and was obliged to return. |

First Lord Baltimore.

39. The First Lord Baltimore.—Among the most important counsellors of James I. was his Secretary of State, George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore,[30] who had been connected with both the London and Plymouth Companies. His interest in colonial matters was such that he obtained a patent for a colony in Newfoundland; but the enterprise failed in spite of his personal efforts (1621). Later he tried to get a footing in Virginia with some of his fellow-religionists (for he was a stanch Roman Catholic); but the Protestant settlers would not have them (1629). Then he secured a charter from King Charles I. for a tract which, although north of the Potomac River, was within the original bounds of Virginia. The new province was named Maryland, after Queen Henrietta Maria. Lord Baltimore died before he could utilize his grant; but his son, Cecilius Calvert, inherited it and became almost a feudal sovereign in the new region. He could declare war, appoint all officers, and confer titles. The freemen of the colony were to assist him in making laws which required no supervision in England; and the colonists were granted an unprecedented amount of religious liberty.

Cecilius Calvert,

Second Lord Baltimore.

40. The Growth of Maryland.—In November, 1633, Leonard Calvert, brother of Cecilius, crossed the ocean with two hundred colonists, and the next year the town of St. Mary’s was founded. Trouble soon arose with a prominent Virginian, William Claiborne, who had previously established a colony on Kent Island, within Baltimore’s jurisdiction. Claiborne was finally expelled, and the colonists, although many of them were Protestants, settled down peacefully. Disputes, however, soon arose with Cecilius Calvert over laws which the freemen insisted on passing; but no serious trouble occurred until the Civil War broke out in England. Then the Protestants gained the upper hand, and in 1645 Leonard Calvert was forced to flee to Virginia. He soon returned, however, and governed until his death, in 1647. After this, considerable confusion ensued; and when Virginia had been secured for the Parliamentarians (§ 42), Claiborne, who had cherished his grievances, compelled Governor Stone of Maryland to renounce his allegiance to Lord Baltimore. When Stone repudiated this agreement, Claiborne, who was a parliamentary commissioner, with the aid of an armed force deposed him, and Maryland passed under the control of the Protestants, who would not allow Roman Catholics to vote or hold office. Cromwell, however, forbade interference with the rights of the Second Lord Baltimore, and Stone, the latter’s legal representative, endeavored to overthrow the Puritan government of the colony, but was defeated in a battle at Providence in 1655. Two years later, Baltimore, through the favor of the English Parliamentarians, recovered his proprietorship and obtained control of Maryland, after a compromise had been made with the Puritan colonists and their Virginia abettors. Greater privileges were granted to the freemen, and there was a general religious toleration. Then followed the excellent administration for fourteen years (1661–1675) of Charles Calvert, the eldest son of Cecilius, who at the end of that period became the third Lord Baltimore. During his governorship many Quakers and foreign immigrants were attracted to the colony, which produced fine crops, notably of tobacco.

41. Revolts of Fendall and Coode.—In 1681 there was a slight revolt, led by a demagogue named Josias Fendall, who had previously been treacherous to the proprietor. He was aided by John Coode, a retired clergyman, and by some Virginians. The uprising was easily put down and would not have made headway had not the people been disturbed by an unpopular local law about the suffrage and by religious and economic legislation in England (§ 43). Another revolt in 1689, led by Coode, was more successful. But in two years the revolutionists were driven from power, and Maryland was made a royal province, the proprietor becoming merely a landlord.[31]

42. Virginia under Berkeley’s First Administration.—We have seen that the royalist governor, Harvey, caused the Virginians at first to regret the gentle rule of the London Company. In 1639, however, Sir Francis Wyatt succeeded Harvey, and affairs began to improve. Three years later, Sir William Berkeley began his long and checkered career as the king’s representative. He was a brave, well-educated gentleman, but full of passions and prejudices that often brought him into conflict with the colonists. His opposition to all efforts to make the colonial government more liberal was intense. He disliked Roman Catholics and hated Puritans; hence such followers of Baltimore and such New Englanders as happened to enter Virginia’s borders, were soon made uncomfortable, as were also the Indians, who were vigorously put down in 1644. Berkeley and most of the Virginians sympathized with Charles I. in his struggle against Parliament to such an extent that after the death of that monarch the governor invited Charles II. to come to America. Charles was too wise to accept, but several thousand cavaliers did come, and thus the colony waxed strong.[32] Parliament did not fail, however, to assert its supremacy. It appointed, as its commissioners, William Claiborne, who had played such a disturbing part in Maryland affairs and was an enterprising trader, and Richard Bennett, a man of prominence and excellent character. It also sent a frigate to the Chesapeake; and with no struggle Berkeley was superseded in 1652 by Bennett, who was elected by the Burgesses. He and his successors ruled well, on the whole, and the colony prospered.

43. Virginia under Berkeley’s Second Administration.—With the Restoration in 1660, Berkeley, who had been living quietly on his estate, was recalled, and then a period of disturbance set in. Severe measures against the Puritans alienated them. Enforcement of the Navigation Act, which compelled colonists to ship tobacco to English ports alone and to receive European goods only from vessels loaded in England, bore heavily on all classes. Then again, Charles II.’s grant of the province to two of his dissolute courtiers, Lords Arlington and Culpepper, naturally caused indignation. At the same time the bad condition of the church in the colony, and the corruption of the public officials, called for correction. The Puritans tried to revolt in 1663, but were suppressed, and matters grew worse. Berkeley became despotic and refused to call a new House of Burgesses, the old House elected in 1660 holding over and actually passing a law restricting the suffrage under which new elections would be held. To crown all, the Indians began to murder frontier settlers; but the governor, who feared printing presses and schools, feared the native militia also, and would not allow them to attack the savages.

44. Bacon’s Rebellion.—At this juncture, Nathaniel Bacon, a young member of the council, brave, honest, and hot-headed, raised, without orders, a private force and defeated the Indians (1676). Berkeley resented this unauthorized action and declared Bacon and his followers rebels. For several months a petty civil war went on, good fortune being with Bacon, who drove Berkeley out of Jamestown, and burned the place. The revolt would not have reached such dimensions had not the general situation been intolerable; but it was bound to be practically local, whatever may have been Bacon’s schemes for a general colonial uprising against the Crown. Even as a local movement it was soon ended, for Bacon’s premature death (October, 1676), whether from poison or fever, left no one to oppose Berkeley. The latter returned to power and continued his tyrannical course, executing no less than twenty-three of the leading rebels. This disgusted Charles II., who had shown much mildness toward his rebellious subjects in Great Britain. So Berkeley was recalled to England in 1677, and died there shortly after in disgrace.

45. Berkeley’s Successors.—The Virginians hailed his departure with bonfires; but in spite of his faults, Berkeley’s career is a pathetic one. He had not moved with the times. His successors in office, on the other hand, moved too fast, for they imitated the corruption of the court at London and overawed the colonists in addition to taking money from them. There were six of these governors in twenty-one years. They quarreled with the Burgesses and kept the colonists in a ferment of riots and hangings; yet the population grew, and some progress was made. A new capital was established at Williamsburg, and the College of William and Mary was founded there in 1692 by Rev. James Blair.

Sir Henry Vane.

46. The Progress of Massachusetts.—Although the colony of Massachusetts Bay had a most vigorous start, it was not without its troubles from the beginning. The governor’s “assistants” soon tried to concentrate power in their own hands, but the freemen (who, by law, must be church members) resisted, and a representative house was inaugurated. Voting by ballot was introduced in 1634, but it was not until ten years later that the administration of affairs was thoroughly organized under a governor and two houses. The migration of such leading Puritans as Sir Henry Vane the younger,[33] and the proposed coming of others, did not serve to put down the democratic tendencies of the colony, which was daily increasing in population and wealth, much of the latter being due to the fisheries and the coasting trade. As a rule, the colonists were of the educated middle class, thoroughly religious and devoted to their pastors, many of whom were very able men. One of these clergymen, John Harvard,[34] by means of a legacy and the gift of his library, assured the founding of the first college in the country, which has since grown into the great university at Cambridge that bears his name.