* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

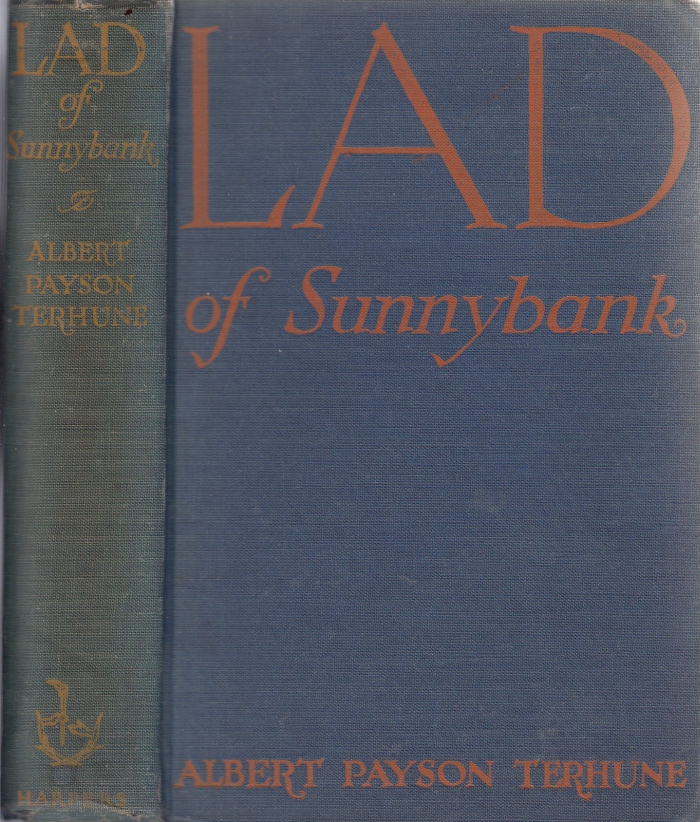

Title: Lad of Sunnybank

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: Albert Payson Terhune (1872-1942)

Date first posted: Apr. 14, 2016

Date last updated: Apr. 14, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160418

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Lad of Sunnybank

Albert Payson Terhune

First published 1929

To

Lad’s Many Thousand Friends,

Young and Old, Everywhere,

My Book Is Dedicated

TO THE READER

About eleven years ago my earliest stories of Sunnybank Lad appeared in book form. It is more than fifteen years since the first of these was published in the Red Book Magazine.

The stories themselves had no claim to greatness, nor even to literary merit. I know that as well as you do. But Laddie was great enough to counterbalance any defects of his chronicler, and to bring unlooked-for success to my tales of his adventures and of his strange personality.

Better than that, the stories won for the grand old collie a host of friends, both here and in Europe, friends to whom he was as real as though they had known him in the flesh.

Many of those friends have written to me, again and again, asking to hear more about Lad.

So I have ventured to write this latest book, hoping to please Lad’s old-time admirers and perhaps to gain other friends for him, by making our long-dead collie chum live anew in its pages.

Albert Payson Terhune

“Sunnybank”

Pompton Lakes

New Jersey

(1929)

| 1. | THE WHISPERER |

| 2. | THE GUEST |

| 3. | THE VARMINT |

| 4. | OLD MAN TROUBLE |

| 5. | CHANGELINGS |

| 6. | THE RINGER |

| 7. | LAD AND LOHENGRIN |

| 8. | DOG DAYS |

| 9. | “HOW’S ZAT?” |

| 10. | “OUT OF THE DEPTHS” |

Lad of Sunnybank

Down the winding and oak-shaded furlong of driveway between Sunnybank House and the main road trotted the huge mahogany-and-snow collie. He was mighty of chest and shoulder, heavy of coat, and with deep-set dark eyes in whose depths lurked a Soul.

Sunnybank Lad was returning home after a galloping hunt for rabbits in the forests beyond The Place.

On the veranda of the gray old house sat the Mistress and the Master, at the end of the day’s work. At the Mistress’s feet, as always, lay Wolf, the fiery little son of Lad. Gigantic Bruce—dog without a flaw—sprawled asleep near him. Behind the Master’s chair snoozed Bruce’s big young auburn son, Bobbie.

Ordinarily these collies would have fared forth with their king, Lad, on his rabbit hunt. But, this afternoon, one and all of them had been through the dreaded ordeal of a scrubbing at the hands of Robert Friend, The Place’s English superintendent, and one of the other men.

Lad had recognized the preparations for this loathly flea-destroying scrub and had seen the disinfectant mixed in the bath-barrel. So he trotted off, alone, to the woods, unseen by the other dogs or by the men.

Lad loved his swims in the lake at the foot of the oak-starred lawn. But he abhorred the evil-smelling barrel-dip—a dip designed to free him of the fleas which begin to infest every outdoor long-haired dog with the full advent of spring.

When the Master chanced to be at hand to supervise the dipping, Lad remained, always, martyr-like, to take his own share of the ordeal. But today the Master had been shut up in his study all afternoon. Lad ever refused to recognize any authority save only his and the Mistress’s. Wherefore his truant excursion to the woods.

Wolf glanced up from his drowse before Lad had traveled halfway down the driveway, on his homeward journey. Wolf was The Place’s official watchdog. Asleep or awake, his senses were keen. It was he that had heard or scented his returning sire before any of the rest. The Mistress saw him raise his head from the mat at her feet, and she followed the direction of his inquiring glance.

“Here comes Laddie,” she said. “Robert was looking all over for him when he dipped the other dogs. He came and asked me if——”

“Trust Lad to know when dipping-day comes around!” laughed the Master. “Unless you or I happen to be on hand, he always gives the men the slip. He——”

“He’s carrying something in his mouth!” interposed the Mistress—“something gray and little and squirmy. Look!”

The great collie had caught sight of his two human deities on the veranda. He changed his trot to a hand gallop. His plumed tail waved gay welcome as he came toward them. Between his powerful jaws he carried with infinite care and tenderness a morsel of tawny-gray fluff which twitched and struggled to get free.

Up to the veranda ran Lad. At the Mistress’s feet he deposited gently his squirming burden. Then, his tail waving, he gazed up at her face, to note her joy in the reception of his gift.

Forever, Lad was bringing things home to the Mistress from his woodland or highroad walks. Once the gift had been an exquisite lace parasol, with an ivory handle made from an antique Chinese sword—a treasure which apparently had fallen from some passing motorcar.

Again, he had deposited at her feet a very dead and very much flattened chicken, run over by some careless motorist and flung into a wayside ditch, whence Lad had recovered it.

Of old, a run-over chicken or dog or cat was all but unknown in the sweet North Jersey hinterland. Horses and horse drivers gave such road-crossers a fair chance to get out of the way; nor did horses approach at such breakneck pace that too often there could be no hope of escape.

Today, throughout that same hinterland, as everywhere else in America—though practically never in Great Britain—pitiful little wayside corpses mark the tearing passage of the twentieth-century juggernaut.

The slain creatures’ owners pay for the smooth roads which permit speed to the invading motorists, thus becoming in a measure the motorists’ hosts. The intruders reward the hospitality not only by murderously reckless speed, but by stripping roadside woods and dells of their flowering trees—usually leaving the fragrantly beautiful trophies to wilt and die in the cars’ tonneaus and then throwing away the worthless trash before reaching their day’s destination.

Where once there were miles of flowery dogwood and mountain laurel and field blossoms bordering the roads, there are now desolation and the stumps of wrenched-off branches and uprooted sod, which mingle picturesquely with chicken bones and greasy paper and egg shells and other pretty remnants of motor-picnickers’ roadside lunches.

In one or two states an effort has been made to curb reckless driving by erecting white crosses at spots where some luckless pedestrian has been murdered by a speeding car. In these states the motorists have protested vigorously to the courts; begging that the grim reminders be removed, as the constant sight of them mars the fun of a jolly ride.

But nowhere have crosses or other warnings been raised over the death-places of car-smashed livestock; nor to mark the wastes where once bloomed glorious flowers. There would not be enough crosses to go around, if all craftsmen toiled night and day to turn them out.

It used to be said that grass never again grew where Attila, the raiding Hun, had ridden. Attila was a humane and tenderly considerate old chap, compared to the brainless and heartless and speed-delirious driver of a present-day installment-payment car.

Lad had shown deep chagrin when the Mistress recoiled from the long-dead and much-flattened chicken he had brought home to her and when the Master ordered it taken away and buried. Carefully the dog had dug it up again evidently thinking it had been interred by mistake. With wistful affection he had deposited it on the floor close beside the Mistress’s chair in the dining-room, and he had been still more grieved at the dearth of welcome which had greeted its return from the grave.

The Mistress looked with dubious curiosity at today’s offering he had just brought her. Even before he laid it down on the floor the other dogs were pressing around in stark excitement. Lad stood over his find, baring his teeth and growling deep down in his furry throat. At such a threat from their acknowledged king, not one of the other collies—not even fiery Wolf—dared to come closer.

The Mistress stooped to touch the grayish creature her chum and worshiper had brought home to her from the forests.

It was a baby raccoon.

Unhurt, but fussily angry and much confused by its new surroundings, was the forest waif. It snarled at the Mistress and sought peevishly to dig its tiny milkteeth into her caressing fingers. Instantly Lad caught it up again, holding it deftly by the nape of its neck, as if to show the Mistress how the feeble infant might be handled without danger of a bite.

As she did not avail herself of the hint, he laid the baby raccoon down again and began solicitously to lick it all over.

How he had chanced upon the creature, back there in the woods, nobody was ever to know. Perhaps its mother had been shot or trapped and the hungry and helpless orphan’s plight had touched the big collie’s heart—a heart always ridiculously soft toward anything young and defenseless.

In any event, he had brought it home with him and had borne it at once to the Mistress as if begging her protection for it.

“What are we to do with the wretched thing?” demanded the Master. “It—”

“First of all,” suggested the Mistress, “I think we’d better feed it. It looks half starved. I’ll get some warm milk. I wonder if it has learned how to eat.”

It had not. But it learned with almost instant ease, lapping up the milk ravenously and with a tongue which every minute spilled less and swallowed more. Its appetite seemed insatiable. All the while it was eating, Lad stood guard over the saucer, inordinately proud and happy that his forest refugee had been rescued from starvation.

“He’s taken the little fellow under his protection,” said the Mistress. “I suppose that means we must keep the raccoon. At least till it can fend for itself. Then we can turn it loose in the woods again.”

“To be killed by the first pot hunter or the first stray cur that comes along?” queried the Master. “That is the penalty for turning loose woodland creatures that have been tamed. When you tame a wild animal or a wild bird and then let it go free, you’re signing its death warrant. You take away from it the fear that is its only safeguard. No; let’s send it to a zoo as soon as it can live there comfortably. That’s the better solution.”

The Mistress’s gaze roved over the placid sunset lawns, to the fire-blue lake and then to the rolling miles of hills and of springtime forest. She said, half to herself:

“If I had my choice, whether to leave all this for a cramped cage and to spend my life there, behind bars, with people staring at me or poking at me—or to go to sleep forever—I should choose the sleep. It’s pitiful to think of any forest creature changing its outdoor heritage for a zoo. I hate to visit such places. It always gives me a heartache to see wild things jailed for life, like that.”

“All of which,” growled the Master, “means you’ve made up your mind you want to keep the measly little cuss here, for always. But——”

“Lots of people have told me a tame raccoon makes a wonderful pet,” observed the Mistress, with elaborate dearth of interest. “And I’ve always wanted one, ever so much. So—so, we’ll do exactly whatever you think best.”

“Sheer hypocrisy!” groaned the master. “ ‘Whatever I think best!’ That means you and Lad have decided to give this forlorn brute a home at The Place. All right. Only, when it eats up all our chickens and then gets killed by the dogs, or when it murders one of our best collies (they say a raccoon is a terrible fighter), don’t blame me.”

“If you’d rather we didn’t keep it,” said the Mistress, demurely, as she stroked the fuzzy gray fur of the food-stupefied wisp at her feet, “why, of course, we won’t. You know that . . . What shall we call it? I—I think Rameses is a wonderful name for a pet raccoon. Don’t you?”

“Why Rameses?” argued the Master, glumly.

“Why not Rameses?” demanded the Mistress, in polite surprise.

“I don’t know the answer,” grouchily admitted the defeated Master. “Rameses it is. Or rather he is. I—I think it’s a hideous name, especially for a coon. Let’s hope he’ll die. Lad, next time you go into the woods, I’ll muzzle you. You’ve just let us in for a mort of bother.”

Lad wriggled self-consciously, and stooped again to lick smooth the ruffled fur of Rameses. This time the little raccoon did not resent the attention. Instead, he peered up at his adopters with a queerly shrewd friendliness in his beady black eyes. His comedy mask of a face seemed set in a perpetual grin. The food had done wonders to reconcile him to his new home.

He reared on his short hind legs and clasped Lad’s lowered neck with his fuzzy arms, his sharp snout pressed to the collie’s ear, as if whispering to him.

The Master snapped his fingers, summoning the other dogs. They had been standing inquisitively at a respectful distance, while the feeding went on, being warned by Lad’s growl not to molest his protégé.

Now, at the Master’s signal, they pressed again around the newcomer, while Lad looked up at the man in worried appeal.

The Master pointed down at the suddenly pot-bellied baby, attracting the collies’ attention to him. Then he said, very slowly and distinctly to them:

“Let him alone! Understand! Let him alone!”

The Law had been laid down—the simple dictum, “Let him alone!” which every Sunnybank dog had learned to understand and to obey, from earliest puppyhood. Henceforth, there was no danger that any one of that group of collies would harm the intruder.

“Sometimes,” said the Master, casually, “I wish we hadn’t taught these dogs to obey so well. If one of them happens to forget, and breaks Rameses back, I’ll forgive him. . . . I hope they all understand that. But I know they don’t.”

So it was that The Place’s population was increased by one tame raccoon, Rameses by name. And so it was that the raccoon’s education began.

The Mistress was delighted with the way in which her new pet responded to the simple training she gave him. She “had a way” with animals and was a born trainer. Under her care and tutelage Rameses not only grew with amazing rapidity, but he developed as fast, mentally, as had Lad himself in puppy days. There seemed almost nothing the raccoon wouldn’t and couldn’t learn—when he chose to.

He had the run of The Place and he obeyed the Mistress’s whistle as readily as did any of the dogs. Even the Master conceded, after a time, with some reluctance, that the coon was an engaging pet, except for his habit of being asleep somewhere in a tree top at the very moment his owners wanted to show him off to guests.

The collies, all except Lad, gave somewhat cold reception to Rameses. They did not transgress the Master’s command to “let him alone.” But they regarded him for the first few months with cold disapproval, and they slunk away when he tried to romp with them.

Little by little this aversion wore off, and—if with reservations—they accepted him as one of the household, even as they accepted the Mistress’s temperamental gray Persian kitten, Tippy. All of them except Wolf. Wolf made no secret of his lofty aversion to the foreigner.

Lad, from the start, had constituted himself the coon’s sponsor and guardian. It was pretty to see him in a lawn-romp with the fuzzy baby; enduring unflinchingly the sharp play-bites of Rameses, and unbending as never had he unbent toward any of the grown dogs.

One of Rameses’ quaintest tricks was to rise on his hind legs, as on that first day, and to thrust his pointed nose against Lad’s ear, as if whispering to the dog. Again and again he used to do this. Lad seemed to enjoy it, for he would stand at grave attention, as though listening to something the coon was confiding to him.

“I’m sure he’s telling Laddie a secret when he does that,” said the Mistress.

“Nonsense!” scoffed the Master. “We’re not living in fable-land. More likely the pesky coon is hunting Lad’s ear for fleas. Likelier still, it’s just a senseless game they’ve invented.”

“No,” insisted the Mistress. “I’m certain he really whispers. He——”

“The only worthwhile thing Rameses ever does, so far as I can see,” continued the Master, refusing to argue, “is his washing of everything we give him to eat, before he’ll taste it. They say that’s just as much a coon trait as the ‘whispering.’ But it shows a grain of intelligence and a funny love for cleanness. He tried to wash a lump of sugar I gave him today. By the time he had rinsed it in his water dish and scrubbed it between his black palms till he thought it was clean enough, there wasn’t any of it left.”

The affection between their huge collie and the ever-growing Rameses amused the two humans, even while it astonished them.

They watched laughingly the many absolutely pointless games played by the dog and his queer chum—Lad’s blank expression when the coon interrupted one of their romps by climbing—or rather by flowing—up the side of a giant oak, with entire ease, whither the dog did not know in the least how to follow; their gay swims together in the lake, and Lad’s consternation at first when the coon would sink at will deep under the water and remain there for a whole minute at a time before sticking his pointed nose and beady little eyes above the surface again.

Nourishing food, and plenty of it, was causing Rameses to take on size and strength at an unbelievable rate; the more since he’d eked out his hearty meals by daily fishing excursions along the lake-edge, whence he scooped up and devoured scores of crayfish and innumerable minnows.

His little black fore claws were as dexterous as hands and tenfold swifter and more accurate. They could feel out a crayfish or mussel from under submerged rocks at will. They could clutch and hold the fastest-swimming minnow which flashed within their prehensile reach.

By the time he was a year old Rameses weighed nearly thirty pounds. At about this time, too, he showed his capacity to take care of himself against any ordinary foe.

One day his fishing trip, along the lake-edge, carried him around the water end of a high fence which divided The Place from an adjoining strip of land. Through the underbrush of this strip a mongrel hound was nosing for rabbits. The hound caught sight of the raccoon, and rushed him. Rameses stood up on his hind legs, the water above his haunches, and grinningly awaited his charging foe.

As the mongrel leaped upon him, Rameses shifted his own position with seeming clumsiness, but with incredible speed. He shifted just far enough for the cur’s snapping teeth to miss him.

In the same instant he clasped both his bearlike little arms with strangling tightness around his enemy’s neck, and suffered the momentum of the hound’s forward plunge to carry him backward and far under water, not once relaxing his death clasp from about the dog’s neck.

Under the surface vanished coon and mongrel together, with a resounding splash. The water eddied and swirled unceasingly above them, for what seemed several minutes to the Master who witnessed the battle from a fishing-boat a quarter-mile distant, and who rowed with futile haste to the spot.

The Master arrived above the seething tumble of deep offshore water just in time to see Rameses’ sharp nose and grinning mask merrily from the depths.

The mongrel did not rise. The coon’s bearlike strangle-hold had done its work.

Aware of an unbidden qualm of nausea at the grinningly matter-of-fact slayer, the Master picked Rameses out of the water by the nape of his neck and deposited him in the bottom of the boat.

Unconcernedly, Rameses shook himself dry. Then, spying a slice of bacon-rind bait lying on the gunwale, he reached for it, washed it with meticulous care in the bait-well, and proceeded to eat it with mincing relish. Apparently the mere matter of a canine-killing had passed out of his mind.

But a man clumping fast through the underbrush of the sloping bit of wasteland was not so philosophical about the hound’s fate. The man was one Horace Dilver, a ne’er-do-well small farmer who lived a bare mile from The Place.

Dilver had taken his mongrel hound out, in this non-hunting season, to teach him to course rabbits. From the high-road above the lake the man had marked the patch of brushy slope as a promising hiding-place for rabbits, and had sent his dog into it. Thus from the road, he had seen the sharply brief battle with the raccoon. Down the slope he ran, yelling as he advanced:

“I seen that coon of yourn tackle my pore Tige and kill him!” he bellowed to the Master. “If I had my gun with me—”

“If you had your gun with you,” rejoined the Master, “you wouldn’t be breaking the game laws any worse than you did by making your hound course rabbits in September. I’m sorry for what happened, but it was the dog’s fault. He pitched into an inoffensive animal, half his size, and he got what was coming to him.”

“I wouldn’t of took fifteen dollars for Tige!” the man was lamenting as he glowered vengefully at the placidly grinning and bacon-munching Rameses. “I love that dog like——”

“Yes,” put in the Master, bending again to his oars. “I’ve noticed your love for him. My superintendent tells me your neighbors complained because you used to beat him so brutally when you came home drunk, that his screaming kept them awake at night. Last week I saw you kick him half across the road, when I was driving by. Couldn’t you find any easier way of showing your inferiority to a dumb animal than treating him like that? He’s lucky to be free from an owner like you. You have no case against me for what my coon has done, and you know you haven’t. You and your dog were both trespassing.”

He rowed on homeward, leaving Dilver splitting the noonday hush by a really brilliant exhibition of howled blasphemy.

Rameses perched, squirrel-like, high on the boat’s stern seat. He grinned sardonically back at the fist-shaking and cursing farmer. Then the raccoon fell to nibbling in epicurean fashion at what was left of the bacon rind.

As the boat drew in at its dock, the Mistress came down from the lawn above. With her was Lad, who had just come home with her from a walk to the village.

The big dog ran joyously to the boat, to greet its two passengers. As the keel grounded, Rameses stood up on his hind legs. As ever, after even a brief absence, he flung his hairy arms around Lad’s hairier throat, his mouth close to the collie’s ear, with the odd semblance of whispering secrets to his chum. He seemed to be telling the interested Lad all about his exploit.

The Mistress smiled at sight of the clinging arms and the earnest “whispering,” and at Lad’s usual grave attention to it.

The Master did not smile. That gently embracing gesture of the coon’s brought keenly back to him a nauseous memory of the arms’ strangling strength, and of Rameses’ grinning unconcern at the slaughter of Tige.

Briefly the Master told his wife what had happened.

“Horrible!” she exclaimed with an involuntary little shudder. With her hand rubbing the slayer’s head, as if in compunction for her momentary distaste, she continued: “But it wasn’t Rameses’ fault. You say yourself he didn’t start it; and he would have been killed by the hound if he hadn’t been just an instant quicker. He isn’t at all to blame.”

“Maybe not,” assented the Master. “But just the same, it was an uncanny thing to do—to drown the antagonist he couldn’t thrash with his teeth! Nothing but a raccoon would have thought of such a trick. I read, long ago, of a wild raccoon killing a dog that way. . . . I wish Horace Dilver hadn’t been the man who owned the mongrel, though.”

“Why not? Is he—?”

“I’ve heard queer things about Dilver. For instance, Titus Romaine’s four cows got into Dilver’s corn and spoiled most of it. Romaine wouldn’t pay damages. A week later all four of his cows were found dead in their stalls one morning. Slosson’s police dog bit one of Dilver’s children in the ankle. It was only a scratch. But the dog was dead a few days later. The vet thought he had eaten meat with powdered glass in it.”

“Oh!”

“Dilver is a sweet soul to have as an enemy! I hope he won’t decide to kill Rameses, as he just threatened to. If he does, we’re likely to have a squabble on our hands. More neighborhood feuds start over livestock killings than over everything else put together. We—”

The Master broke off, to make a futile grab at Rameses. The raccoon had finished his whispered colloquy with Lad. Then he had thrust his arm into the fish-creel the Master had laid down on the boat-house bench. Drawing thence a two-pound black bass, Rameses was washing it scrupulously in the lake-edge water, preparatory to eating it.

On an evening less than a week after the killing of the mongrel the Master and the Mistress went to an early dinner given by some friends of theirs at the Paradise Inn, at the foot of the lake. The maids were at the movies, over in the village. Bruce was asleep in the Master’s study, where his nights were spent. Wolf, vigilant as always, lay on a porch door mat outside the front door, alertly on duty.

Through the early dusk Wolf saw two shapes making their way in leisurely fashion down the dim lawn and toward the lake. One was Wolf’s bronze-and-white sire, Lad. The other was a low and shambling creature, less than half the big collie’s height.

Well did Wolf recognize Lad and Rameses, and well did he know his sire was accompanying the raccoon on one of the latter’s frequent nocturnal fishing expeditions along the shore.

Yet he forebore to leave his mat and trot along with them, not only because he was officially on guard, but because he still had a sullen dislike for the raccoon.

The other dogs had learned to tolerate Rameses comfortably enough. But Wolf’s hotly vehement prejudices could not brook any acquaintance at all with the outsider. Wherefore, having long ago been bidden to “let him alone,” Wolf kept out of Rameses’ way as much as possible.

These fishing jaunts of his coon chum were always of mild interest to Lad. He himself did not understand the art of fishing; nor did he eat raw fish. But manifestly he enjoyed strolling along the bank and watching Rameses, stomach deep in the water, feel for crayfish under stones or dart beneath the surface with paws and nose together and emerge in triumph with a tiny and wiggling minnow tight gripped.

There was something about his coonlike form of hunting which seemed to appeal to Lad’s ever-vivid imagination and to his sense of fun. Head on one side and tulip ears pricked, he would spend hours at a time, an amused spectator at Rameses’ minnow-and-crayfish-catching antics.

Tonight the coon worked his way northward, along the shore of The Place, toward the bridge. As on the day when he fought Tige, he swam around the water-jutting end of the fence which divided The Place’s north boundary from the strip of bush-slope that ran from the lake to the highway.

Lad swam at his side. When they had rounded the fence end, the collie waded ashore, shaking the water from his vast coat. The coon began, as before, to crawl, stomach-deep, in the shallows, in quest of fish.

Presently Lad raised his head and growled softly. He heard and scented an alien human presence moving furtively toward him from the highway above. This was no human of Lad’s acquaintance. Moreover, the collie was no longer on his master’s land. Wherefore, he felt no need or duty to bar this stranger’s way or otherwise to stop his advance.

Lad knew every foot of The Place’s forty acres, and he had been taught from puppyhood that humans were not to be interfered with unless they should trespass thereon. This bushy slope was no part of The Place. Thus the furtively approaching human’s presence was no concern of Lad’s.

The growl was not a threat or a menace. Rather was it a mode of notifying his coon chum of the man’s approach; or else it was a mere reaction on meeting a human, at dusk, in so isolated a spot.

Horace Dilver did not descend by mere coincidence or accident through the impeding thickets toward the lake’s margin, this September evening. He was a patient man. Half a dozen times, during the summer, when he was passing along the shore, he had happened to see the dog and the coon on one of their evening fishing tours. He had noted that this stretch of bank was one of their favorite haunts at such times.

Thus, with deadly patience, he had repaired to the highroad every evening at sunset, since the day when his hound had been strangled by Rameses.

Time meant little to Dilver, and revenge meant much. Soon or late, he was certain, the two chums would fish in that direction again. The time had come sooner than he had dared hope. And Dilver was ready. Dilver had a habit of being ready—except perhaps for work.

Under one arm he held a right formidable and nail-studded club, tucked there ready for use in case of necessity. But he did not expect to be called upon to use it. There were better and safer ways.

Were the dog and the raccoon to be found with their skulls smashed, the Master might get to remembering Dilver’s blasphemy-fringed threats and there might be trouble. But if both animals should be taken agonizingly and fatally ill, soon after their return home, who could prove anything against anybody? Nobody had been able to prove anything in the cases of the poisoned cows and of the police dog.

Besides, Dilver had heard neighborhood brags of big Laddie’s prowess, and he did not care to attack so formidable a dog, unless as a last resort. He knew—everyone knew—how devoted were the Mistress and the Master to the great mahogany collie. To kill him at the same time he killed the raccoon, that would be double payment for the drowning of Tige and for the Master’s unloving remarks to himself.

The man drew near and nearer, among the lakeside bushes. After the first involuntary growl, Lad paid no further attention to him. Naturally, having a collie’s miraculous sense of smell and of hearing, Lad knew to the inch whither each stealthy step was leading the ever-nearer human.

At an instant’s voice Lad could have located and sprung at him as Dilver skulked closer with awkward attempt at soundlessness and concealment. But it was none of Lad’s business to assail men who chose to slink along on neutral territory. As to the thought of possible danger to himself—fear was one emotion the great dog never had known.

Rameses was equally aware of the man’s approach, and he was equally indifferent to it. Humans—except the friendly folk of The Place who had tamed and trained and brought him up—meant nothing and less than nothing in the raccoon’s self-centered life. Besides, he was nearing a most seductive school of minnows which took up all his spare attention.

Then the rank human smell was augmented by a far more seductive odor—the scent of fresh raw meat. Dilver had drawn from a pocket a greasy parcel and was unwrapping it.

Something sped through the air, close to Lad’s head. The collie, with wolflike swiftness, darted to one side, growling savagely and baring his fangs. If this human were going to throw things at him, the aloof neutrality was at an end.

But, even as he snarled, Lad saw and smelled what the missile was, and his new-born anger died. This was no rock. It was a gift.

It struck the very edge of the lake, midway between the dog and Rameses, and it lay there in the dusk; a chunk of raw red beef, perhaps three ounces in weight, and rarely fascinating to any normal four-legged meat-eater. Rameses saw it at the same time.

Strong as was the temptation, Lad drew back from the luscious morsel, after the first instinctive advance. Had the meat been found lying there, he might or might not have eaten it. But he had heard the man throw it to him and it bore the scent of Dilver’s hand.

Always Lad had been taught, as had others of the Sunnybank collies, to accept no food from an outsider.

This is a needful precaution for dogs that go to shows—at which more than one fine animal has been poisoned—or for dogs that have a home to guard and must be prevented from accepting drugged or poisoned meat. Lad had learned the rule, from his earliest days.

He halted in his advance toward the chunk of beef, reluctantly turning away from its lure and thereby saving himself from a peculiarly hideous form of death.

But Rameses had had no such teachings, and probably would not have profited by them if he had. After a second of polite waiting, to see if Lad intended to share the feast with him, the coon picked up the meat, holding it squirrel-wise between his palms. Horace Dilver grinned almost as broadly as did Rameses himself.

Daintily the coon dipped the meat deep into the water; washing his food, as always, before eating it. Thoroughly he scrubbed the chunk between his handlike claws. In the midst of this rubbing process he paused, allowing the beef to fall uneaten into the shallows.

Blinkingly, the raccoon peered down at his black paws. The palm of one was cut. A drop of blood was oozing from it. The other palm was scratched lightly in two or three pieces.

The vehement washing and kneading and rubbing had pulled open the carefully interfolded envelope of meat. Its contents—a half-teaspoonful of powdered glass—had excoriated the washer’s hands.

Rameses let the meat sink out of sight in the water, while he stared grinningly at his scored palms. Something was wrong here. A hundred times he had washed meat, and never before had it turned on him and scratched him like this. Irritant stuff which will tear the hands will hurt the mouth and stomach, too. Experience with sharp fish fins had taught that simple fact to Rameses, long ago.

Horace Dilver ceased to gloat pleasantly-over his ruse. For some unexplained reason these two creatures were rejecting a lure to which other victims had yielded without a moment’s hesitation. Disappointment and an hour of mosquito bites and a naturally filthy temper combined to sweep away the man’s hard-held patience.

Even if it were not safe to tackle that great brute of a collie, yet it would be easy enough to brain a silly pet raccoon and then to tie a stone to it and toss it far out into the lake.

Dilver pounced suddenly from behind the screen of bushes and caught Rameses by the nape of the neck, lifting him aloft with one hand while in the other he poised his studded club. Thus had he brained unwanted puppies and kittens.

But his knowledge of raccoons was rudimentary.

For one thing, he did not know that the loose skin of a grown coon’s neck enables him to twist about, when held thus, as easily as if the skin were an overlarge collar.

Rameses never had liked handling; though he endured it, when necessary, from the folk of The Place. Now, at this alien and roughly painful grip, the coon twisted himself sharply.

Into the fleshy part of Horace Dilver’s thumb flashed Rameses’ double set of buzz-saw teeth. The upper and lower teeth met and ground together in the flesh.

With an echoing screech of torment, Dilver let fall the raccoon and danced about, sucking his mangled hand. The flung Rameses landed as lightly on the ground as might any cat. He crouched there, snarling up at the dancing man in utter hate.

Lad, too, turned back from his homeward journey, at the sound of strife. Teeth bared, he faced the anguished Dilver, starkly ready to resent any further possible attack upon his loved protégé.

Out through the death-still night rolled that initial pain-screech of Dilver’s, and the less piercing but equally agonized yells which followed upon it. These latter were muffled by reason of an alternate sucking of the hurt; but they carried far.

The Mistress and the Master had returned early from Paradise Inn. They were just getting out of the car at their own door when Dilver’s first bellow was wafted to them.

“Some one is drowning out there—close off-shore—just a little way to the north!” exclaimed the Mistress.

The Master did not wait to hear her out. He broke into a run, making his stumblingly rapid way northward along the bank as fast as he could cover the dusky and uneven and wooded ground.

He had not gone ten steps when Wolf raced past him, traveling at windspeed in the same direction. His deities safely at home, Wolf could afford to abandon his post as watchdog and to gratify his ever-keen curiosity as to what all the fuss was about.

Wholly unaware that his cries had started human and canine investigation, Horace Dilver ceased presently from sucking his bleeding hand and groped for the studded club he had dropped. Pain had changed his wrath into maniac rage. The creature which had bitten him should pay full and immediate penalty.

Mouthing and cursing, he swung the club upward and rushed at the snarling Rameses.

The coon had been more than a little entertained, through all his own indignation, by the noisy and saltatory antics of this human. Even Lad had ceased his menacing advance and had paused to behold and listen to the strange performance.

When the club whizzed aloft, Rameses did not dodge out of the way. Never had he been struck. His year on The Place, as the Master had foreseen, had deprived him of the precautionary fear which has saved the lives of so many wild things.

But Lad was wiser. The collie sensed the awful peril to his little chum and he launched himself at the club’s wielder. He was a fraction of a second too late.

Down crashed the nail-bossed club, impelled by all the fury-strength of a strong man. It smote the grinningly unflinching Rameses full athwart the furry shoulders—a blow which would have killed an animal of double his size.

Before the club could be raised for a second blow—before it had fairly struck the first—Dilver felt himself hurled forward by a smashing weight of eighty pounds which flung itself full upon the middle of his broad back.

Before the forward-plunging man’s body could hit the stony ground of the lake margin, a double set of teeth were at work at the back of his neck and the base of his skull, accompanied by a ferocious growling that sounded like a rabid beast worrying its prey.

Over and over rolled the bawling man, down the remaining yard or so of the steep slope and into the water itself. On him and all over him ravened Lad, striving ever to reach the jugular.

The dog knew well what must have been the result of such a smashing blow as his little friend, Rameses, had received from this human brute. The dog’s mighty heart was hot and sick and raging within him at the loss of the pal he had found and had brought up so lovingly.

Again and again Lad drove for the throat, Dilver shoving him away as best he could and striving vainly to rise or recover the club which had flown from his hand as he fell.

Once, with hammering forearms he thrust back the avid jaws. Through coat and shirt sleeve and deep into the arm the terrible teeth clove their way. But Lad abandoned this non-lethal hold and drove afresh for the throat.

It was then that a red-gold meteor-like thing burst through the bushes.

Wolf did not know what it was all about. On the ground he saw a writhing and tortured mass that so lately had been the merrily grinning Rameses. On the ground, too, a few yards away, half in and half out of the water, he beheld another writhing and tortured mass—a human, this time—with Sunnybank Lad seeking industriously to throttle him.

That was all Wolf saw. That was all Wolf cared or needed to see. Gleefully he whizzed forward to the fray; gripping the nearest part of Dilver’s anatomy, then changing his grip for a better. Under the irresistible onslaught of the two furious dogs, Dilver gave himself up for lost.

With all his remaining strength he sought to roll himself—since they would not let him rise—into deeper water, in an attempt to dive, and thus to escape them. But, as if they caught the meaning of his plan, both collies assailed him together from the lakeward side, blocking this one sorry hope of safety.

It was then that the Master came up. The flashlight which he had jerked from his fall-overcoat pocket revealed a gruesome scene, there at the water’s edge. His horrified shout of command made the two dogs draw back in fierce unwillingness from their victim.

By the Master’s aid, Dilver got to his feet. The man was all but naked. His body was scored by an alarming patchwork of bites. He was blubbering, gasping, praying, half dead with panic terror. He staggered a step or two, then sat down drunkenly on a rock, chattering and sobbing in violent hysterics.

The Master turned from him and stared about in stupid wonder, trying to discover what might have been the reason for the turmoil.

His flashlight fell on a piteous tableau. On the ground Rameses was huddled. He lay in a posture which Nature never intended nor permits. Above him stood Lad, his deep-set eyes infinitely sad, his whole statue-like body adroop.

There was a crashing through the bushes. Lad did not stir or glance up as the Mistress and The Place’s superintendent hurried forward. They came to a halt, of wonder, at the picture disclosed by the flashlight’s white ray.

The crushed body of Rameses stirred. The beady black eyes opened. The grinning little comedy mask of a face was raised slowly toward the sorrowing dog that bent above it.

Then, inch by inch, Rameses lifted his stricken body. By sheer effort of torment he reared himself waveringly on his haunches.

His arms went around Lad’s neck. His pointed nose was buried against the collie’s listening ear. Once more he was “whispering.” Lad seemed to listen, as with heart-sore attention, and to understand.

The clinging arms relaxed. The furry gray body slumped lifeless to the ground at his collie chum’s feet.

Lad stooped and picked it up, holding its dead weight between his powerful jaws as tenderly as when he had brought the baby Rameses to The Place so long ago.

Then, moving unswervingly, and carrying his dead playmate with that same mother-like gentleness, he made his way up the slope and onward toward the very heart of the far-off forest—the forest whence once he had brought his little comrade.

The superintendent took a step, to follow. The Mistress intervened.

“No,” she whispered. “Let him go. Lad knows. Lad always knows. I—I think Rameses told him what to do, and he is doing it. Let him go. The—the Wild is going home to the Wild.”

She came to The Place on the strength of a sheaf of letters of introduction which would have gained admittance for Benedict Arnold into the Sons of the Revolution. The letters were from European friends to whom the Mistress and the Master owed much in the way of courtesies and hospitality.

Wherefore Mrs. Héloïse Lejeune was invited to spend a week at The Place, on her arrival in America on a tour which was to serve as basis for a series of lectures in her own Latin country. She accepted the invitation with much alacrity.

“Everything in life has to be paid for,” grumbled the Master as he and the Mistress sat in their car at the rural railroad station, waiting for the guest’s belated train. “And always it has to be paid for at the most inconvenient times and in the most inconvenient way. Debts that can be settled in cash are the easiest to wipe out. The others are the really tough ones. They make me wish there were a moral bankruptcy court I could go through.”

“But we—”

“We didn’t want to visit at any of those houses in England and Scotland and France,” said the Master. “We’d have had a better time and a less expensive time at hotels or village inns. And now, of course, three of our loving hosts are ‘collecting,’ by sawing off this Lejeune woman on us as a guest—at a time when I ought to be working twelve hours a day and when you want to get those songs of yours finished. Why couldn’t she—”

A reassuring pat on his shoulder made the Master turn in annoyance toward his wife.

The Mistress was not a shoulder-patter, and he wondered glumly why she should choose this irritating mode of trying to dispel his crankiness. But her gloved hands were resting lightly on the car’s steering-wheel—even as the pat was repeated with insistent vehemence.

Not a hand, but an absurdly small and very white paw, was tapping the man’s shoulder.

A huge collie had been lying lazily on the rear seat. At the peevish note in the Master’s voice the dog had risen in sudden worry, and had shown quick sympathy for his god’s unknown trouble by patting eagerly at the nearest part of the man’s anatomy.

The Master’s scowl changed to a reluctant grin as he leaned back and rumpled the collie’s classic head.

“Lie down, Laddie,” he said. “It’s all right. Or if it isn’t, you can’t make it so by swatting my shoulders with your dusty feet. This is the only clean white suit I have left.”

The dog stretched out again on the seat, his plumed tail wagging. Lad was well content. The tone of annoyance was gone from the Master’s voice. Apparently everything was all right again. That was all Lad wanted to make certain of.

“Mrs. Lejeune wrote that beautiful essay in verse, on dogs, for one of the English magazines,” the Mistress was saying. “So she must like them. I wouldn’t have brought Lad over to meet her unless her essay had shown such a splendid understanding of—”

“Mrs. Lejeune didn’t write it,” was the Master’s morbid contradiction. “Maeterlinck wrote it. She took most of the best things in his ‘My Friend The Dog,’ and rhymed them and put them into her own words. Just the same, she wouldn’t have done it if she hadn’t liked dogs. That’s the one bright spot—or the least unbright spot—in the thought of having her at Sunnybank with us for a whole interminable week. She—”

The behind-time train hooted dismally as it neared the station. The Master left the car and strode along the platform to meet the guest.

A minute later he returned, convoying a large and grenadier-like woman whose walk and demeanor gave somehow the impression that she was leading a ceremonial parade of ancient Egyptian priests.

The Mistress had signaled Lad to jump over to the front seat at her side, leaving the tonneau to Mrs. Lejeune and the Master and to an extensively labeled array of hand-luggage which a station porter distributed as best he could between and around their feet.

With lofty graciousness and with an ever-so-slight foreign accent, Mrs. Lejeune acknowledged the Mistress’s greeting. Then she stiffened at sight of the great mahogany-and-snow collie that nestled at her hostess’s side on the front seat.

Lad returned her unloving look with an icy gaze of aloofness. Then, with his tulip ears flattened close to his head, he turned his back on her.

There was chill insult in the collie’s manner. He did not like this newcomer. One glance had been enough to settle that fact in his uncannily psychic mind. He did not like her, and he saw she did not like him.

The Mistress and the Master, in the order named—these two were Sunnybank Lad’s deities. To them, from puppyhood, he had given eager and worshiping service. The rest of mankind did not interest him. But to most of The Place’s guests he accorded a cold courtesy. Toward none of them had he showed the affronting and affronted distaste which he bestowed on the large Mrs. Lejeune.

“This is Laddie,” the Mistress was explaining to her visitor, speaking fast and trying to ignore the collie’s rudeness. “I know how fond of dogs you are, so I—”

“I am not!” denied Mrs. Lejeune with charming frankness. “I detest them. I find them either gleesome or fleasome. When they are gleesome they smear their muddy paws on people’s white dresses. When they are fleasome, they—”

Laddie created a diversion at this point in the guest’s harangue. A right alluring and thrilling scent had assailed his keen nostrils so potently as to banish momentarily his disgust at this noxious stranger. The scent exhaled from a square black satchel the porter was lifting into the car from the heap of luggage on the platform edge.

Lad leaned far over the back of the seat, sniffing at the satchel with pleased interest. From a tiny wire grillwork at one end of the bag a sharp hiss rewarded the poke of his exploring nose. The hiss was followed by a fretful yowl which rose in timbre and volume until it merged into a second and more irate hiss.

Instantly Mrs. Lejeune’s lofty manner changed to solicitous tenderness. She bent over the satchel, lifting a corner of its lid and crooning softly into the interior:

“There, there, Massoud darling! The filthy brute sha’n’t bother you. He—”

Mrs. Lejeune’s promise was broken well-nigh before it was made. The inch-wide opening of the bag’s top was vastly entertaining to the inquisitive Lad. In merry expectation he nosed at the crack, to widen it for better inspection. Mrs. Lejeune aimed a corrective slap at him. The slap did not reach its target.

For the joggled lid flew wide, by reason of sudden internal pressure. A shapeless gray paw flashed forth—a paw equipped with a set of pinlike claws. Lad shrank back instinctively, with his nose tip adorned by three red furrows. At the same instant Massoud, a large and gray and frantically spitting Persian cat, whizzed forth from the satchel into a new and unfriendly world.

“Kittykittykitty!” wailed Mrs. Lejeune, imploringly, as she grabbed for the escaping cat.

But Kittykittykitty rewarded the effort at capture by sideswiping virulently her owner’s large, fat hand as it sought to seize her flying gray form. The same leap carried Massoud clear of the car and onto the station platform. Thence, without breaking her stride, she made a dash for the far side of the tracks.

Elated at the jolly adventure which had come so opportunely into his staid life, Lad gave chase. Before either the Mistress or the Master could guess at his intent, he was out of the car and galloping in mischievous pursuit. The whole thing happened in a fraction of a second.

Now, Massoud was in about as much danger of harm from Lad as would be a duck from immersion into a pond. The great collie had the fighting pluck and prowess of a tiger. But never had he harmed any creature smaller and weaker than himself. His meeting with the suddenly abhorred Mrs. Lejeune had somehow aroused in him the perverse imp of mischief that never sleeps any too soundly at the bottom of a collie’s nature.

He could not wreak his dislike on Mrs. Lejeune herself. Not only was she a woman, but also she was very evidently a guest.

And from babyhood Lad had understood and obeyed the rigidly simple guest-law of The Place. But he could and would pester her and at the same time add to his own fund of amusement, by chasing harmlessly the cat she had crooned to so lovingly.

Toward the tracks catapulted the fugitive, ears flat, tail enormous, the shapeless gray legs carrying her over the ground at an amazing pace. Close behind galloped the big collie, mischief in every inch of his giant body and in his deep-set eyes. Lad was having a beautiful time.

The Mistress was first to find voice.

“Laddie!” she called. “Lad!”

Almost in midair the charging collie checked his run. Always had he obeyed that soft voice. Nearly always, hitherto, he had rejoiced to obey it. But now his obedience was solely a matter of lifelong duty. Humans had such a silly way of interrupting, just when sport was at its height.

He halted disgruntedly, and made as though to come back to the car. Then, changing his purpose, he stood stockstill for an instant, while the mischief and even the reluctance went out of his eyes, leaving them troubled and alert.

Massoud had sped across the nearer of the two railroad tracks beyond the side platform. But as she struck the farther track she was aware of a sinister buzzing of the rail beneath her galloping paws and of a dismaying roar that ripped at her temperamental nerves.

Glancing sidewise as she ran, she beheld a gigantic black bulk rushing down at her.

The New York express was thundering southward, making no stop at this unimportant country station.

Massoud saw it looming above her. Strength and sense deserted her at the sight. She had reached the far rail of the express track. On it she crouched—helpless, shuddering, her glazed green eyes fixed on the onrushing locomotive.

It was this which had caused Lad to check his leisurely return toward the car and to the Mistress who had summoned him thither. Seated beside the Mistress in that same car, not a month ago, he had seen a stray kitten cut in two as it meandered across a railroad track in front of a train. Well did the dog realize Massoud’s sickening peril.

The Master saw also. Even as the cat came to a paralyzed standstill on the rail, the man moved the bulk of his shoulders between his guest and her pet’s impending slaughter.

Mrs. Lejeune thus missed seeing Massoud’s terrified pause, though, nursing her scratched hand, she sought to follow the chase by peering around the Master’s interfering shoulder.

She filled the air with denunciatory lamentations and with shrill demands that the murderous dog be recalled from his pursuit. Neither of her hearers gave heed.

For, as the express bore down upon the cat, a swirl of sunlit orange-tinted mahogany fur flashed across the track, under the very prow of the engine’s cowcatcher. Sunnybank Lad had gone into action.

Seemingly bent on a hideous form of suicide, the mighty collie hurled himself at lightning speed in front of the roaring train. Across the track he sped at the incredible pace known to no dog but collie and greyhound. As he sprang, he dipped his head earthward, without abating one jot of his fiery speed.

Then the express, traveling at nearly sixty miles an hour, cut off the onlookers’ view of the scene.

The guest continued to whicker forth her wild commands. The Mistress stared at the obstructing train’s spinning wheels with bone-white face and hard-set mouth. Unconscious of what he did, the Master swore softly and venomously, as an accompaniment to Mrs. Lejeune’s screeched prattle.

A million centuries crawled by. Then the express was gone, leaving a blinding eddy of cinders and dust and smoke in its wake. Through the murk stared the Mistress and the Master, their gaze studying the gleaming rails, with sick horror for signs of what they dreaded.

On the far side of the track, perhaps twenty feet beyond the rails, stood Lad. From between his mighty jaws dangled and squirmed and writhed and yowled a mass of gray fur. He was holding the rescued Massoud deftly and gently by the nape of her furry neck, even as he had snatched her up during his shrewdly judged dash across the track.

Through the maze of dust and cinders Mrs. Lejeune caught her first semi-distinct view of the situation. She saw her adored cat twisting futilely in the grip of a huge dog—a dog seemingly bent upon breaking her neck.

With a dexterity foreign to women of her size, she darted across the track and grabbed her imperiled and indignant cat, holding the squalling and spitting and scratching feline hysterically to her breast—and at the same time aiming a fervent kick at Lad.

The kick caught the dog full in the ribs, painfully and humiliatingly. In all Laddie’s three years of life, never before had he been kicked. At The Place dogs were not punished in that way, the Master believing that man can find better ways of showing his inferiority to dumb brutes than by kicking them. The unprecedented assault staggered the collie. He whirled on the assailant, his curved white eyeteeth agleam from under his upcurled lip.

Had a man other than the Master done this fool thing to him, Lad would have been all over the aggressor before the punitive foot could have touched ground again. But this was a woman, and Lad contented himself with snarling loathingly up into her rage-purpled face. Then, majestically, he strode back to where the Mistress and the Master stood.

He thrust his muzzle into the Mistress’s cupped hand for comfort and for praise. He got both.

With difficulty the Master swallowed words which would have shamed The Place’s hospitality. Then he said to his wife:

“Drive home with her. Try to explain what really happened. I can’t explain it to her. If I tried to speak to her now, I’d say things I could be jailed for. I’m going to walk. Come along, Laddie.”

Thus began a visit which to this day is remembered at The Place as might be an epidemic of smallpox. On Lad it bore harder than on the humans. Always, from further back than he could remember, the collie had been as free throughout the house at any and all times as were his owners. But now everything was different.

In the first place, the obese guest with the faint Continental accent, and the temperamental Persian cat, was ubiquitously present, and the presence shattered for Lad the sweet peace of the home he loved.

They hated him, these two intruders; they made no secret of their hate. Moreover, an hour after their arrival, the Mistress had led the collie to a kennel down near the stables, and very gently had made him understand this was to be his abiding-place for the time. He was forbidden the house—he who had been the house’s guard and honored inmate from puppyhood!

Worse, his queerly sensitive mind told him the Mistress was wretchedly unhappy and that the master was in a continuously villainous temper.

The great dog grieved bewilderedly over these manifestations of malaise in the two humans he worshipped. True, both of them contrived to hide their state of mind from the guest, but no slightest shade of human mood can be hidden from a chum collie.

Exiled and worriedly sad, the dog moped miserably around The Place, welcoming with pathetic eagerness his very few chances to romp or walk with the Mistress or the Master, during such times as one of them was free from the entertaining of their guest.

Also there were dinners, and at least one tea and a garden party, in Mrs. Lejeune’s honor. Such functions implied the presence of many outsiders. Lad hated crowds.

Mrs. Lejeune did not scruple to tell all and sundry the story of Lad’s supposed attempts to kill her darling Massoud. Nor did she hesitate to reiterate to everyone that the very sight of a dog nauseated her. In that dog-loving hinterland community—especially among The Place’s intimates, who were fond of Lad—she won scant popularity.

“Why did you write that essay poem, praising dogs, if you hate them so?” asked the Master once, when she had been holding forth on this chronic dislike of hers.

“Why did your American poet, Fergus Ager, write exquisite child-poems, when he abominated brats?” she countered. “Why did the English poet, Brunning, write that deathlessly beautiful horse-ballad of his, when he shuddered at the sight of a horse?”

“I don’t know,” said the Master. “Why?”

“Children and dogs and horses are popular themes with the masses,” explained Mrs. Lejeune. “Anything written about them is certain of popularity, if it is well done. For that matter, it is common knowledge that the most inspired dogbook ever written was by a Britisher who not only did not own dogs, but who was afraid of them. He told me that when he came to America to lecture, people used to insist on bringing their horrible dogs for him to see, and it was the worst ordeal that he ever went through. Now, cats—especially Persian cats—”

“Yes,” vaguely assented the Master, “now, cats. Especially Persian cats—”

He broke off to watch Massoud craftily stalking an oriole that was singing its heart out from the summit of a tiny veranda-side shrub. At The Place, song birds of every kind were as much at home as was Lad himself. No cat or other animal was allowed to molest them. As a result they were as tame as chickens and they nested by scores among the thick veranda vines.

Now, for the first time, a Sunnybank song bird was annoyed by a Sunnybank human. The Master flung his pudgy tobacco-pouch at the oriole. The bird, in fluttering surprise, broke off its song and flew away—just as Massoud completed her stalking preliminaries and sprang for her escaped victim.

“Yes,” repeated the Master, apropos of nothing at all, “especially Persian cats. We have two cats of our own. One of them is a Persian. Tippy, you know. We are fond of them both. We’ve had them for years, and they’re part of our household. They leave the birds alone, and the dogs leave our cats alone. It’s all a matter of simple early training.”

Gloomily he watched the mincing progress of Massoud across the lawn toward the lake edge. Along the bank were bushes where nested innumerable small birds.

Lad also noted the progress of the detested Massoud, from the kennel where he lay in unhappy solitude. The Mistress’s early command of “Leave her alone, Laddie!” had rendered the Persian cat immune from further jocose harrying by the law-abiding collie.

But now, as she made her dainty way over the sward in the direction of the lakeside bushes, the command seemed harshly difficult to obey. There was a full hundred yards of lawn between the cat and the lake, and an increasingly wide space between her and the protection of the house.

It would be glorious fun to whiz out in chase of her. Of course, he would not harm a fuzzy hair of her when at last he should overhaul her. But the chase would be a delight.

Then, sighing, Lad resigned himself to the dull cheerlessness of lying inert in his kennel while a million attractive things waited to be done.

The Mistress and the Master—they were with that odious big woman who loathed him and whom he loathed. The house, with his cool “cave” under the piano—that too was denied him while Mrs. Lejeune should remain at The Place.

This peculiarly teasable alien cat—she must be left alone. His human deities were distressingly unhappy about something. That was the worst phase of all, to Lad, in this period of interminable unpleasantness.

Drowsily his eyes continued to follow the lakebound cat.

No longer was the Master watching Massoud’s progress from the veranda and speculating surlily on the probable killing of one or more of the trustful birds whose nests dotted the shore bushes. He had just been called indoors, to the telephone. The Mistress also had gone into the house a minute earlier to give orders for dinner. Mrs. Lejeune was left alone on the shaded porch.

The air was lazily warm and athrob with bird songs. The lake lay fire-blue at the foot of the emerald lawn and amid its circle of softly protecting hills. From the rose-garden drifted faintly a myriad sweet odors. Mrs. Lejeune’s poetic soul expanded under the loveliness of it all—as might the soul of an elephant at scent of a ton of circus peanuts.

She smiled as she saw Massoud draw near to the first of the lakeside bushes, and saw the mincing gait of the cat merge into a tigerish crawl. The dear little pet had discovered an unsuspecting bird somewhere in the bush. That was evident. She was creeping up on her prey with that lithe grace which her owner so admired in her.

Better to see the stalking process, Mrs. Lejeune left her veranda chair and started down the lawn amid the ancient oak trees, toward the water’s edge. She moved slowly and on tiptoe, lest sound of her approach disturb the absorbedly creeping cat.

She came into the line of Lad’s vision. The dog’s upper lip curled instinctively, showing once more a glint of the terrible white eyeteeth. Then, in chill contempt, he looked once more at the craftily moving cat—the cat he had been bidden to leave alone.

As Mrs. Lejeune neared the bank, Massoud halted, crouching low and swishing her great feathery tail. The cat’s jaws chattered. Her whole body was aquiver.

Then, gauging her distance, she launched herself at a slate-hued catbird that was singing on a twig midway up the bush.

Of the infinite variety of birds which made Sunnybank their summer abiding-place—a cloud of them staying all winter to feast on the ample daily rations of suet and crumbs doled out to them—the catbirds were loved by the Mistress and the Master better than all the rest combined.

As a result, catbirds nested in the big lilac clump near the house and in even nearer shrubbery, and were as tame as canaries. One or two of them even used to alight close beside the Mistress’s feet on the veranda floor during breakfast and lunch, sometimes singing gloriously, sometimes pertly demanding food. They seemed to know of these two humans’ protective fondness for them.

Nearly all singing birds have but a single song—two or three or four notes which they repeat over and over in changeless iteration. But a catbird has a repertory. His song lasts sometimes for several minutes; soft, divinely sweet, shifting from one theme to another without repeating itself.

Even more beautiful and varied than the mockingbird’s is the catbird’s changeful song. (Both of them excel, by far, the nightingale, as singers.) The catbird seems to be making up his music, afresh, as he goes on in his song, and to be improvising with conscious skill.

True, once in a way, he seems to be making fun of his own poetic chant by breaking it off with a half-disdainful and wholly mischievous catcall. But this startling contrast only intensifies his song’s beauty.

As a mimic he has no equal. For hours he will try to imitate the oriole’s four-note call, until he has learned it so perfectly that human ears cannot detect the difference between it and the original (and indignant) oriole’s. It is the same with his deftness in catching and copying the songs of two or three other varieties of birds.

It is not a chance repetition. As I have said, he will try for hours, sometimes, before he has reproduced another bird’s song flawlessly and to his own satisfaction. Nor will he cease until he has achieved the task. About him, too, is found a strain of elfin mischief, a true and keen sense of fun. And he is gaily fearless. I have seen him drive a five-foot black snake from his babies’ nest, and chase the squirming monster for more than a hundred yards; pecking in punitive rage as the shining black head, yet clever enough to elude the snake’s jaws or his coils.

So much for a digression, which perhaps is not so much of a digression, after all; as it explains the tameness of the catbird which Massoud was stalking and the affectionate welcome it and its kind had always found at The Place.

Massoud sprang upward and outward, toward the bush. It was a good pounce—powerful and well judged. But a scud of rain had fallen during the night. The lakeside grass was damp and slippery.

In the take-off, Massoud’s driving hind feet slipped ever so little. Not enough to spoil her leap, but enough to make it fall short of its goal by some three or four inches.

Thus, instead of digging deep into the feathers and flesh of a luckless songster, Massoud’s foreclaws found themselves scrabbling desperately for a purchase hold amid a mesh of brittle twigs.

Away flew the bird, in wrathful amaze at such treatment. The cat clawed with all four feet to keep from falling through the interlacing little branches into the deep water below.

There she hung, squalling and clawing, unable to move forward or back, and hard put to it to avert a tumble into the lake.

Lad lifted his head from his white paws and gazed with new and genuine interest. This promised to be very entertaining indeed.

Mrs. Lejeune was running forward in an agony of apprehension, calling shrilly for someone or anyone to help her in extricating her cat from this peril of a ducking. The lake bottom shelved down at that part of the bank, with no intermediate shallows. Massoud must needs swim if she should fall into the water. And Mrs. Lejeune did not know whether or not cats could swim.

Panting, she hurried to the rescue of her pet. Gripping a handful of the bush twigs and bracing her slippered feet against the steep edge of the bank, she reached far out over the water, grasping for any seizable part of Massoud.

The impulse was laudable, but several laws of nature rendered it a failure.

One of these laws concerned gravitation and the tendency of unbalanced heavy bodies to topple. Another was the aforesaid slipperiness of the lakeside grass. A third was the inability of a handful of thin witch-elm twigs to withstand a sudden tugging weight of the two hundred pounds.

The still summer air was shattered by a calliope-like shriek. Lad saw Mrs. Lejeune’s body shoot forward through space as if it had been shoved violently from behind. Through the unimpeding bush it drove its way and for some short distance farther.

Then once more the abused law of gravitation asserted itself and the unfortunate woman fell with an echoing splash into the smooth blue water.

Massoud was jarred loose from her own precarious hold on the crackling twigs by her owner’s dramatic passage through the bush. The cat landed well out in the lake, whence she swam with entire ease, if with much discomfort, to the safety of the shore.

Mrs. Lejeune was less fortunate. She went clean under. The air billowed her clothes. Her own fat aided in bringing her to the surface like some obese cork.

Spraddled out and making desperate efforts to swim—an art she never had troubled to learn—she gurgled and gasped, seeking to clear her lungs and mouth of water in order to scream afresh for help.

Her shriek, as she fell, had changed Lad’s academic interest in the scene into immediate concern. There was terror in that yell. There was peril in the water.

The dog tore forward at top speed, racing for the lake. He was following the instinct of his kind, heedless of whether the imperiled human were friend or foe.

Mrs. Lejeune’s aimless struggles carried her head under again. With a frantic twist she brought it to the surface. As she did so, her water-bleared eyes, staring in panic glassiness, beheld a mahogany-and-snow body leap from the bank and hit the lake resoundingly, close beside her.

As her head was about to go down again, from the mad uselessness of her own struggles, she felt something grip her shoulder, bearing her up and easing momentarily the mysterious force which was tugging to draw her under.

“Lad!” she gabbled, deliriously, wrenching her body around so as to fling both thick arms about the dog’s throat.

Now, Lad was having enough trouble, without this added handicap. It was no light matter for even so powerful a dog to hold above the surface the head and shoulders of a crazily writhing woman of Mrs. Lejeune’s weight.

When that weight was shifted so as to bear down on his battling forequarters and when convulsive arms squeezed shut his breathing apparatus, and when the woman’s impeding bulk pressed against his chest and pinioned his front legs—the situation waxed acute.

Woman and dog went under water together, both of them helpless. The strangling pain in her nostrils and throat made Mrs. Lejeune loosen her grip on the collie, in order to beat uselessly with her hands in an effort to rise. Freed of the dead weight that was choking and drowning him Lad came to the surface.

A five seconds’ swim would have brought him comfortably to shore. But he was not minded to accept life at the expense of the woman who had half-smothered him. A blur of whitish cloth appeared just below the surface. Lad struck for it and seized it, pulling it upward with all his might.

Luckily his teeth had found the victim’s shoulder once more. A mighty heave brought her head above the water.

Lad churned the lake to foam as he swung the heavy and twisting body sidewise in an attempt to tow it ashore. This time Mrs. Lejeune’s arms missed their clutch for him. Straining every splendid muscle, the dog dragged her shoreward. Faint with fright, she relaxed. Thus, her feet sank and her tall body became almost perpendicular. As a result, she felt the shelving lake bottom beneath her soles.

The solid touch revived her. With a last scrambling summoning of all her strength, she floundered landward. For perhaps three steps she waddled; then her legs gave way and she sat down hard, in some eighteen inches of water. Lad had let go of her shoulder and had splashed ashore. His work was done.

It was then that the Master and the Mistress, drawn by their guest’s first calliope shriek, came running to the edge of the lake.

“It’s worse than when she hated Lad!” sighed the Mistress that evening when, for a minute, she and her husband were alone. “Worse for Laddie, I mean. He was happier out in his lonely kennel than with Mrs. Lejeune trying to kiss him every five minutes, and—”

“Dogs aren’t meant to be kissed,” said the Master. “And when it comes to being kissed by Mrs. Lejeune, the term ‘a dog’s life’ takes on a new and horrible meaning. She says she is going to get the Humane Society to give him a medal—he’d lots rather have a steak bone—and she is going to bring him into her new lecture on ‘Real Life Heroes.’ Poor ol Lad!”

“He behaves beautifully about it, though,” declared the Mistress. “And she doesn’t know enough about dogs to see how he detests being pawed and cooed to by her. It’s an awful reward for saving her life.”

“He didn’t,” contradicted the Master.

“Didn’t what?”

“Didn’t save her life. I know every inch of the lake, all along our shore. The water isn’t more than five feet deep, anywhere, at that part of the bank. If she had had sense enough to try to stand up, instead of spread-eagling, when she fell in, she could have walked ashore. The water wasn’t above her chin.”

“Oh!”

“Don’t tell her that, of course. Lad saved her cat’s life and she hated him. He didn’t save her own life—and she is daft about him. That’s how it goes. But——”

“She has a wonderful idea,” interrupted the Mistress. “I know you’ll appreciate it. She wants us to give Lad to her and to accept her heavenly cat, Massoud in exchange.”

The Master’s mouth flew ajar from the force of a torrent of words that sizzled for utterance. Before they could be spoken, Lad came pacing solemnly past them as they stood on the veranda.

From the house he emerged. He paid no heed to either of his deities as he strode by. In his jaws he was carrying a spangled purple satin girdle which the grateful Mrs. Lejeune had taken from her own ample meridian and had knotted artistically around the disgusted dog’s throat.

Twice Lad had managed to wriggle free of the undesired gift. Twice Mrs. Lejeune had retied it lovingly about his neck.

A third time he had freed himself of it; and now he was bearing it forth into the night. Every line and every motion of his shaggy body was vibrant with grim resolve to be made ridiculous by it no more.

Solemnly he made his way to the nearest flower border. There his white little forepaws wrought vehemently in the soft loam until he had dug a hole nearly a foot deep.

Into this cavity he dropped the garish purple satin ornament. With his nose for a shovel he pushed the loose earth over it until the hole was filled.

Then, with a last disgusted look toward the house whence Mrs. Lejeune’s voice could be heard calling tenderly to him, he slunk away to the Lejeuneless sanctity of his own kennel.

The Master came up from the direction of the stables, a gun in the crook of his arm, his eyes bleared, and his hair tumbled. He looked as if he had been up all night, as indeed he had.

At his side paced majestically the huge bronze-and-snow collie, big Sunnybank Lad.

The Mistress had just come downstairs to breakfast. Catching sight of her husband, she went forth to meet him. Dainty and well groomed and gaily fresh of aspect from her night’s sleep, she formed a stark contrast to the disheveled man.

“What luck?” she hailed him, adding, “But if you had fired it would have waked me, I suppose. So——”

“So we drew blank, Laddie and I,” answered the Master. “It wasn’t Lad’s fault. He didn’t know what we were there for. But it was mine,” he continued, shamefacedly, “because I must have gone dead asleep out there on that rottenly uncomfortable stump. One minute it was pitch dark. The next minute the east was all gray. I’m a grand sentinel! It happened while I was asleep. Three more of them gone, this time. And it’s all my fault, for drowsing. Next time I’ll——”

Down the driveway plodded the rural delivery postman. He was an oldster who had been one of the Master’s fishing and swimming and hunting companions when the two were boys, there in the North Jersey hinterland.

“Special-deliv’ry letter for you, Boss,” said the postman as he came up to the group. “I——Hello! What’s the gun for? They must have changed the game laws hereabouts since yesterday, if there’s anything that’s legal to shoot in June.”

“There is something ‘legal to shoot,’ ” returned the Master. “And I spent the night trying to shoot it. But I’m getting old. Remember how you and I used to sit up all night waiting for the bass to strike at daybreak? Well, this time I fell asleep. I was watching for something or someone that has been looting my chicken-yard and taking from one to three of my best prize fowls every few nights. It was a ‘something,’ though, not a ‘someone.’ Lad would have nailed any human prowler. It——”

“Sure,” assented the postman. “And that means it was a varmint.”

“Whatever it was, it was clever enough to outwit Laddie and me.”

“Don’t go smearing half the blame onto the Big Dog, Boss,” expostulated the postman. “ ’Twasn’t up to him. He’s a watchdog. That means he’s on the watch for folks, not for varmints. Where was you watching from?”