* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Where Highways Cross

Date of first publication: 1895

Author: J. S. (Joseph Smith) Fletcher (1863-1935)

Date first posted: Apr. 11, 2016

Date last updated: Apr. 11, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160411

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

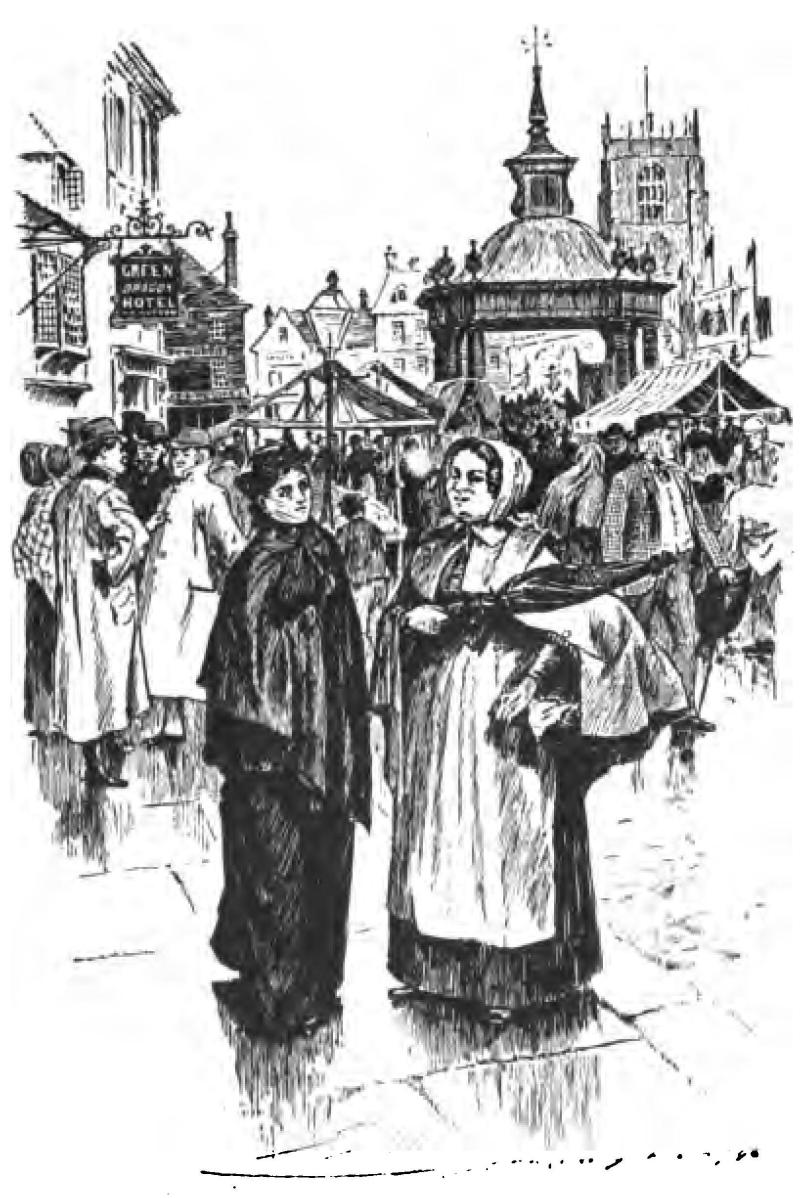

On the direction of a friendly countrywoman.

Frontispiece.

Copyright, 1895,

By MACMILLAN AND CO.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith

Norwood Mass. U.S.A.

| PART THE FIRST—ELISABETH | |

| I. | THE STATUTE HIRING FAIR |

| II. | THE FASTENING PENNY |

| III. | THE HOME FARM |

| IV. | HEPWORTH |

| V. | THE VILLAGE CHAPEL |

| VI. | PARTIAL CONFIDENCES |

| PART THE SECOND—WHERE HIGHWAYS MEET | |

| I. | ST. THOMAS’S DAY |

| II. | HEPWORTH SPEAKS |

| III. | ELISABETH’S HISTORY |

| IV. | NO OBSTACLES |

| PART THE THIRD—THE EVE OF THE WEDDING | |

| I. | A HEART’S FIRST LOVE |

| II. | ANTICIPATIONS |

| III. | THE BLOW FALLS |

| IV. | HEPWORTH’S QUESTION |

| V. | TEMPTATION |

| VI. | WHERE HIGHWAYS CROSS |

Outside the town of Sicaster, going north-by-north-west, the high-road leads through a somewhat level country, mainly concerned with coal-mining, towards the great city of Clothford, thirteen miles away. On this side of Sicaster the land has few features of interest or beauty. Here and there stands an ancient mansion, embowered in trees and shielded from contact with the unlovely colliery villages by carefully-fenced parks and enclosures. In the villages themselves the observant traveller often finds traces of old houses which were no doubt picturesque and countrified in the days when agriculture was preferred to coal-mining. The greater part of the district, however, is somewhat dingy and dark, and the lover of nature sees little to admire in it. But within two miles of Sicaster the scenery shows signs of change for the better. The high-road becomes suddenly straight, and, leaving the coal-district in the rear, runs along the side of Sicaster Park, a vast enclosure where race-meetings are held twice a year. It rises a little at this point, and in the far distance stands Sicaster itself, a mass of red roofs and grey walls, with the quaint steeple of St. Giles’s Church overtopping the irregular gables and chimneys. Beyond Sicaster there are no more coal-mines. The town once passed, the traveller sees before him the long, rolling meadows and wide cornfields which make Osgoldcross one of the most fertile and beautiful divisions of Yorkshire.

Along that portion of the high-road which runs parallel with Sicaster Park there walked, one November afternoon, some twenty years ago, a woman who was obviously wearied to the verge of extreme fatigue. The day was cold and slightly wet. A thin, intermittent rain came with the gusts of wind that blew fitfully across the park, and the woman, as she walked on, drew her shawl more closely about her shoulders, as if to protect herself from the weather. Coming to one of the bridle-gates opening into the park, she paused and leaned against it. A waggon, drawn by two stout horses, was following her from the direction of Clothford, and she looked back along the road and watched it draw nearer. The waggoner whistled as he came along, and his merry tune was accompanied by the jingle of the brass bells that hung from the head-gear of his horses. As he came abreast of her he cast his eye on the woman by the wayside.

“Will you ride in, missis?” he called across the road. “ ’Tisn’t far, but it’s better riding than walking to-day.”

The woman looked at him doubtfully for a moment, and then, persuaded by his cheery face, or coaxed by the comparative luxury of the canvas-topped tilt under which he sat, she crossed the road with a word of thanks. The waggoner pulled up his team with a jerk, gave her a hand, and helped her to a seat at his side.

“You are very kind,” she said. “I am tired.”

“Aye, I daresay, missis,” he answered. “T’ road’s wet, and bad for walking.”

He started his horses again with a chirruping sound from his pursed-up mouth. The road began to rise thereabouts, and they went slowly. The waggoner resumed his whistling, but twisted his head round to take stock of his companion. At the first sight of her, resting against the bridle-gate, he took her for a tramp, but when she crossed the road and faced him he saw that he had been mistaken. He now saw, on such examination as he could make by surreptitious glances out of his eye-corners, that she was neatly if scantily attired in garments that had obviously been good and of somewhat fashionable style, and that her whole appearance showed unmistakable traces of personal care. She wore gloves and a veil, and beneath the latter the waggoner saw a face that was young and attractive, with delicate features and pathetic eyes, and a mouth that drooped a little at the corners as if with anxiety or grief. He whistled more softly on making these discoveries, but his companion apparently took no heed of the music which he made. Her eyes were fixed on the red roofs that shut in the vanishing point of the long, straight high-road; her hands lay in her lap, the fingers lacing and interlacing each other.

“Nasty day,” said the waggoner at length. “Both for man and beast, as the saying is.”

The woman half turned towards him. Something in the movement suggested to him that she had until then forgotten his presence.

“Yes,” she answered. She turned from him again, and looked once more along the road. “What place is that we’re coming to?” she enquired.

“That, missis? That’s Sicaster.”

She gave a little sigh of relief.

“I’m glad of that,” she said. “It’s a long way from Clothford, isn’t it, when you walk all the way?”

“On such a day as this, missis, why, yes, it is,” answered the waggoner. “A long way indeed.”

He cast further glances at her from his eye-corners, and being of an inquisitive nature, would have liked to ask her why she had walked, seeing that the railway was near and trains were plentiful. The woman, however, showed no further disposition to talk, and he took to whistling again and stirred his horses into a slow trot.

The road now crossed a railway bridge, and after dipping slightly, began to ascend through rows of ancient houses towards the heart of the town. The horses slowed down their pace, and as the jangling noise of their bells became fainter, the waggoner and his companion became aware of the sound of such harsh music as may be made by the beating of drums and cymbals and the blowing of horns and trumpets.

“What’s that?” asked the woman.

“It’s the stattits, missis,” said the waggoner. “Sicaster stattits, and that’s the music of the shows and the wild beasts and such like.”

“What are the stattits?”

“Lord love us, why, the stattits is when all the country-folk come to be hired! There’s rare doings in the Market-Place, I’ll lay a penny. Fat women, and real giants, and men turned to stone, and such things as them. But here we are at the Cross-Keys, and I’m going no further at present, missis,” said the waggoner.

He helped his companion to alight at the door of a little inn which stood at the entrance to a large open space filled at that moment by a bustling throng of people who elbowed and jostled each other as they moved from one show to another. The woman stood on the pavement and looked somewhat helplessly about her. The waggoner tied up his reins to the cart-head, keeping his eye on her the while.

“Can you tell me where the Market-Place is?” she asked him. “I want to find somebody there, and I’ve never been here before.”

“You can’t miss it, missis,” answered the waggoner. “Go straight down—there past the shows—that’s the Corn-market—and through the Beast-fair—and there you are in the Market-Place.”

The woman thanked him for his kindness, and went away in the direction of the noisy crowd. In the Corn-market every available inch of space was occupied by the shows and the people thronging about them. One side of the square was filled up by a menagerie of wild animals. On the platform outside it sat the bandsmen whose drums and trumpets made blaring music that failed to drown the roaring and shrill cries of the beasts inside the vans. The people crowded with a steady persistence up the steps leading to the entrance. Those who had already been inside and who had emerged with faces expressive of wonder, grouped themselves about the entrances of smaller shows, one of which held a wild man, and another a lamb with three heads. Outside each of these frail erections of sail-cloth and canvas there stood a barrel-organ or a gong, and these being continuously ground or beaten, added fresh discord to the babel of sound that arose on all sides. The whole scene was one of noise and hubbub, of jostling and horse-play, and the blowing of the trumpets and beating of the gongs tended to produce a feeling of confusion in anyone who had not previously attended similar gatherings.

The young woman who had ridden into the town with the friendly waggoner made her way along the skirts of the crowd until she came to the Market-Place. Here the scene was even noisier and more perplexing than in the wider Corn-market, for the pavement was lined with stalls at which small hucksters sold sweet-stuffs and cheap commodities, and the space beyond was filled with more shows, round-abouts, and canvas booths. Here, also, the people were more crowded together and seemed to be waiting for something to happen. A row of farm-labourers, some of whom carried whips in their hands, stood on the curb; a crowd of young women, dressed in their best, sheltered under the low roof of the old Butter-Cross. Farmers in stout driving coats and leggings walked about in the throng or chatted in groups at the shop-doors, while young folks and children clustered about the stalls or pushed their way to the fronts of the shows. Arrived there they stood in open-mouthed admiration of the gorgeous paintings that placarded the wonders to be seen inside. At all these things the stranger scarcely looked; her eyes were busily engaged in studying the signs over the shop-doors in the Market-Place. She went along one side of it without finding what she wanted, which was a dressmaker’s establishment in which there was a vacant situation that she had hopes of filling. She found it at length on the direction of a friendly countrywoman, but diffidence or anxiety prevented her from entering it for a moment or two. At last she summoned sufficient courage to open the door and walk into the shop. She came out again in a few minutes with disappointment visibly expressed on her pale face. The vacant situation had been filled up that morning.

The young woman withdrew from the crowd into a quiet alley opening out of the Market-Place, and after making sure that she was unobserved, drew out a shabby leather purse from her pocket and examined the contents. Upon counting the coppers which it contained she found that she had but tenpence. She replaced the purse, and went back into the Market-Place, feeling sick at heart. She had walked from Clothford in the hope of getting the situation for which she had just made application, and her errand being fruitless, she was now in a difficult position.

Wandering aimlessly through the throng she came along the north side of the Market-Place until she reached the Butter-Cross. Here she stood looking hopelessly about her until her attention was arrested by the group of girls and young women who stood on the steps of the Cross, laughing and talking together. She noticed that now and then a farmer and his wife would step up to one or other of these and hold a conversation which seemed to partake of the nature of a bargain. Out of sheer curiosity the stranger enquired of a woman what the girls stood there for. The woman regarded her curiously.

“Why, to be hired, of course,” she answered. “They’re looking out for situations, and they’re mighty particular, too, some on ’em, for servants are scarce to-day.”

The stranger hesitated a moment, and then she made her way through the throng and took her place on the Butter-Cross.

The young women on the Butter-Cross looked at the new-comer with something of wonder and disdain. She was obviously not of their own class, nor fitted for the work which domestic servants are expected to perform in farm-houses. Her pale face and retiring air formed a marked contrast to their own ruddy countenances and confident demeanour. They began to whisper amongst themselves, glancing at the stranger with eyes which were not altogether friendly. She, however, took no notice of them, but stood waiting for someone to accost her. The farmers and their wives, who came into the Cross and looked about them, gazed at her curiously, but did not speak to her. The men wondered who she was, and what she did there; the women, keener in their criticism, decided that all was not well with her. Being somewhat dulled by the disappointment she had just experienced, the stranger did not perceive the effect her presence had produced. Her attitude was one of apathetic expectation; she merely waited to see if anything would happen.

After a time there advanced through the constantly-moving throng a man who paused for a moment at the foot of the steps leading to the Butter-Cross, and looked upward at the people above. He was a tall, broad-shouldered person of apparently forty years of age, dressed in a long grey driving coat which came nearly to his feet, but left a glimpse of his stout leather gaiters. His clean-shaven face was dark and full of character. His eyes were somewhat deep-set in his head, and his mouth, which was full and firm, gave the impression of a strong will that was further deepened by his square jaw and bold chin. He seemed to be of a somewhat superior class to most of the men standing by, and some of these greeted him in passing with more show of respect than they made towards their fellows.

The new-comer glanced at the crowd within the Butter-Cross without any particular sign of interest until his eye fell on the young woman who had just taken up her station there. She still stood looking out upon the throng, apparently taking little notice of what was going on around her. Her appearance showed him that she was a stranger to the place and the people, her indifference to her surroundings told him that she was not of the class of girls who usually offer themselves for domestic service in farm-houses. As she had not seen him, or betrayed no sign of having done so, he felt no compunction in continuing to gaze at her and to study her face, which seemed to him to be a singularly attractive one. Presently he mounted the steps and mixed with the throng. Some of the girls knew him and replied respectfully to his greeting. He walked in and out between them, but after a while returned to the stranger and addressed her.

“Are you looking for a situation?” he said.

The young woman started as if from a reverie and looked at her questioner. The man was regarding her intently, but with a certain kindliness in his eyes which made her reply to him with some confidence.

“I should be thankful for one, sir,” she answered.

“I am wanting someone,” he said, and stopped short as if not sure of what he was about to say. “Have you any experience of domestic service?” he enquired, after a pause.

A little spot of colour came into the girl’s cheeks. The man noticed it quickly, and spoke again before she could answer him.

“I mean of household requirements,” he said. “I don’t want servants so much as someone who could give them a sort of superintendence. Do you know anything of baking, now, or sewing?”

“I know plenty about sewing, sir.”

“Ah, you’ve perhaps been engaged in that sort of work?”

“Yes, sir.”

He looked at her curiously, tapping his boot with the ash stick which he carried in his hand, and obviously disliking to put personal questions to her. The young woman, however, found courage to relieve his embarrassment.

“I was engaged in the dressmaking business at Clothford,” she said, “but my mistress failed in business, and I could not find another situation there. I heard of a place here at Sicaster, so I walked over to apply for it to-day, but it was filled up when I got here.”

“You walked over from Clothford? That’s a long distance on such a nasty day. Why didn’t you take the train?”

“Because I couldn’t afford it, sir.”

“I see—I see. I’m sorry I asked that—I didn’t think what I was saying. Now about this business of mine—I’m a farmer, and I have a strong servant who does all the actual work, but I want someone to see after things a little—not exactly a housekeeper, you know, but somebody that could mend and sew, and keep my rooms tidy, and see that things were as they ought to be. What do you think? Could you undertake that?”

“I think so, sir. I’ve kept house—and I am tidy and orderly, I believe.”

“That I can see. Well, I think we might arrange. You see, I don’t want a young woman such as these behind us. I want something superior—somebody that has a bit of better feeling and knows how things should be done. The setting of a table for dinner, now—could you see to that?”

“Oh yes, sir.”

“And such things as choosing curtains for a parlour, now, or making linen for the house—you could manage all that, I daresay?”

“I’m sure I could, sir.”

“That’s what I want. My old servant—she’s been with me a long time—is very good at plain cooking and at kitchen work, but of course she doesn’t pretend to more. Well, now, what would you say about wages—I haven’t much idea myself.”

“I don’t know, sir. Perhaps I ought to tell you that I was never used to—to this, until recently. But I have no friends, and my husband is—is dead—”

“Yes, yes,” said the man. “Don’t cry—it comes to all of us—but it’s hard, no doubt.”

“And so I had to earn my own living after that,” said the young woman, making a resolute attempt to keep back her tears, “and dressmaking was all that I could do, and lately—”

“I understand. Well, now, what would you say to your board and lodging and fifteen pounds a year? That was what I reckoned to pay for the service I want.”

“I should be glad of it, sir, for I am practically destitute. I would do my best to earn it.”

“Well, I’m sure you would. Perhaps you could give me the name of the dressmaker you worked for in Clothford for a reference. It’s the usual thing to do so, though I suppose it’s fast a form.”

“Oh, yes, sir. It was Mrs. Feather, in Widegate—though, of coarse, the shop is closed now.”

“I know the name. Well, now, we’ll call our bargain settled then, and I hope you’ll try to do what I want. My old servant’s a little bit touchy, but I daresay you won’t disagree with her. Now, what’s your name?”

“Elisabeth Verrell, sir.”

“Very well, Elisabeth—I’ll write it down in my pocket-book. My name is Hepworth—Thorndyke Hepworth—and if you’d like to ask any questions about me, anybody in the fair will answer them, or any of the Sicaster shopkeepers. Well, now, let me see—oh, there’s one thing I mustn’t forget.”

He unbuttoned his long coat and drew forth a leather bag from his breeches’ pocket. From this he extracted a half-sovereign, and held it towards Elisabeth. She looked at it in astonishment.

“What’s that for, sir?”

Hepworth smiled.

“I forgot,” said he. “Of course, if you’re a stranger hereabouts you don’t know the custom. That’s a fastening penny to conclude the bargain. Now, you’ll perhaps be wanting some little thing before I drive home, and if I were you, as it’s a cold day, I’d go and have something to eat—there’s a good eating-house close by—and oh, you’ll be having a box to take, perhaps?”

“No, sir—my box is at Clothford—I must send for it.”

“Very good, Elisabeth. Then go, get your tea, and meet me at the Elephant Hotel at six o’clock—ask the ostler for Mr. Hepworth’s conveyance.”

Hepworth now turned away and went down the steps of the Cross into the Market-Place, where he was presently lost to sight amongst the crowd. Elisabeth watched him wonderingly until he disappeared. She was a little confused at the sudden change in her fortune, and was inclined to ponder over it. She recognised friendliness in the way Hepworth had spoken to her. She had been so lonely and sick at heart until he addressed her that a certain numbness of spirit had filled her mind and made her insensible to much of what was going on around her. Now that there was some definite prospect of gaining an honest living presented to her, her spirits revived, and she left the Butter-Cross with a lighter heart.

Elisabeth made her way to the eating-house which Hepworth had pointed out. She had not tasted food for many hours, and her breakfast, taken at Clothford, had been of poor and unsubstantial quality. She now felt keenly hungry, and entered the eating-house with something like alacrity. The place was well patronised: there were few vacant corners, but she found one near the door and slipped into it. The young woman who waited on customers came to her and recommended her to try ham-and-eggs. The house, she said, was famous for its ham-and-eggs, and the price was moderate. Elisabeth acquiesced: she was famishing, and could have eaten anything that the waitress chose to set before her.

While Elisabeth was enjoying her meal, one of the girls who had stood near her on the Butter-Cross came in and took a seat at the same table. She was a plain-faced country girl, with a kindly expression of countenance, and she had been almost the only one of the crowd not to talk or giggle over the stranger’s appearance. She now looked at Elisabeth with a new interest, and presently addressed her.

“I see’d you talking to Mr. Hepworth,” she said. “Perhaps you’re going to place there. You’ll excuse me for speaking, but I used to live there myself once.”

Elisabeth saw that there was no undue inquisitiveness in the girl’s manner. She replied that she was going to service at Mr. Hepworth’s, as the girl supposed.

“And a rare good master he is,” said the girl, with emphasis. “I should ha’ liked to stay there, but he had one servant already, old Mally, and besides, I had a bad illness. I expect you’ll be going as a sort o’ parlour maid—he’s a very gentleman-like sort o’ man, is Mr. Hepworth, and likes things doing right. He’s a religious man, too: he preaches at the Chapel sometimes. He was very good to me when I was badly—used to read to me for an hour at a time, and buy me things to do me good. I don’t think nobody could find a better place than that. I’m stopping again in my present place, and I wish I wasn’t.”

Elisabeth heard this news with considerable satisfaction, and was not averse to hearing more. But as it was by that time drawing near to six o’clock, and as she had yet to enquire her way to the Elephant Hotel, she said good-afternoon and went away.

When Elisabeth entered the inn-yard she found Hepworth waiting for her. His horse was already yoked to the gig, and he himself was superintending the bestowal of various parcels under the seat. He assisted Elisabeth to climb into the gig, and gave her a rug to wrap about her knees before he got in beside her. Then he drove out of the yard by a back way that escaped the noise and bustle of the fair, and presently turned into a road that led away from Sicaster in the opposite direction to that by which Elisabeth had entered the town. By that time the light rain that had fallen with more or less persistency during the afternoon had ceased, and given place to a clear evening and a starlit sky. Elisabeth, unused to riding at a rapid pace in an open conveyance, shivered a little as the gig emerged upon the unsheltered road.

“You’ll feel the cold, I daresay,” said Hepworth. “I’m used to it, and it makes no difference to me. Now, there’s a spare rug behind—how would it be if you put it about your shoulders?”

He pulled up the horse as he spoke, and reaching the rug from the back seat, assisted his companion in somewhat clumsy fashion, as if he were not used to the task, to wrap herself in it. Elisabeth thanked him, and was glad of the rug—the cold was keen, and her garments were ill-fitted to withstand it.

Hepworth drove on through the darkness, speaking little to Elisabeth, save to enquire now and then if she felt the cold. They passed through a village, the windows of which showed faint gleams of lamp-light, and went onward along a bleak portion of the road over which an ancient corn-mill, faintly defined against the dark sky, stood sentry-like. Then came another village, larger and more straggling than the first, a mere collection of lamp-lighted windows seen fitfully in the darkness. When it was passed the road dipped into a country thickly covered by deep woods, the tree-tops of which showed in tremulous shapes against the sky. Suddenly the horse turned out of the highway into a narrow lane, shadowed on one side by the wood, and after following this for a hundred yards or so, stopped at a gate. Hepworth handed the reins to Elisabeth, and got down from the gig. Having led the horse through the gate and closed it behind them, he regained his seat, and drove forward at a walking pace. Elisabeth perceived that they were traversing the outside of a paddock thickly planted with huge trees whose branches swept the ground. Presently the lights of the house shone out through the darkness, and the gig stopped at the gate of the fold. The kitchen door opened, and a broad stream of light revealed the figures of a man carrying a lantern, and of a woman who stood behind him in the doorway. Hepworth got down from the gig, and assisted Elisabeth to alight. She stood waiting while he gave some directions to the man as to the disposal of the horse. At his bidding she then followed her new master into the kitchen. A middle-aged woman of a somewhat grim, but not unpleasant countenance, stood by the great fireplace when they entered, evidently superintending certain cooking operations which gave forth an inviting odour. She looked questioningly from Hepworth to Elisabeth.

“Now, Mally,” said Hepworth. “I’ve found a young woman to do the bit of work we talked about. Elisabeth’s her name—I’m sure you’ll get on together. I daresay you’ll tell her all that she wants to know, but she’ll be tired to-night, so we won’t ask her to do anything.”

“There’s nowt to do,” said Mally, triumphantly. She looked at Elisabeth, and nodded. “Sit you down, lass—come to the fire. I lay it’s cowd as Christmas outside, and drivin’s a cowd job at t’ best o’ times. Now maister, if you’ll nobbut go into t’ parlour, I’ll see ’at all’s reight—I can’t do wi’ men about me when I’m busy.”

Hepworth laughed, and disappeared into the parlour through a double door. Mally presently carried there a tray loaded with food, and shut the inner door behind her. Elisabeth heard her voice and Hepworth’s in conversation. She looked round her. The kitchen in which she sat was a pattern of tidiness. The big table in the side window-place had been scrubbed to the whiteness of snow; the hearthstone was elaborately decorated with designs in potter-mould; the brass candlesticks on the mantelpiece shone like burnished gold. Elisabeth, strange as the place was to her, felt a sense of peace and security in these evidences of the old servant’s orderliness.

Mally presently returned from the parlour, again closing both the doors behind her. She approached Elisabeth, and laid her hand not unkindly upon the young woman’s shoulder.

“Your jacket’s damp, my lass,” said she. “Off wi’ it, and hang it up ower th’ hearthstone. You shall hev’ a drop o’ tea, scaldin’ hot, to tak’ the cowd out o’ you.”

Elisabeth protested that she had already had tea at Sicaster, but she hastened to follow Mally’s advice as to the jacket.

“A drop o’ good tea, made as I mak’ it,” said Mally, “weern’t hurt nobody. Down wi’ it, lass, while it’s hot. If you’ve hed your tea at Sicaster, you weern’t be wantin’ owt to ate just now, but happen you’ll do wi’ a bit o’ supper later on. There’s no stint in this house for onnybody.”

Elisabeth drank the tea which Mally gave her. It was strong and good, and of an infinitely superior taste and quality to that which she had tasted in the Sicaster eating-house. She said as much to Mally, who sat on the opposite side of the hearth, and drank her own tea out of a pint bowl. Mally wagged her head wisely.

“I tak’ no notice o’ them ateing-houses and their tea,” said she. “It’s nobbut poor wishy-washy stuff at t’ best o’ times, and their bread’s sad, and t’ butter’s sour. I’d rather pine thro’ here to Sicaster and back, and hev’ my own when I get home again, than depend o’ them ateing-houses.”

She then said that as the master would want nothing for a while, she would show Elisabeth the house, so that she might know her way about next morning. Elisabeth assented with alacrity, and followed Mally through various chambers, upstairs and downstairs, all scrupulously clean and old-fashioned, and redolent of soap and water. Before a great chest on the staircase Mally paused and looked at her companion with a significant expression.

“That’ll be your job, lass,” she said. “It’s linen, is that; sheets, and table-cloths, and napery, and the good Lord knows what. The maister’s mother bowt it, and took great store in it, but it hevn’t been so well seen to sin’ she were takken, poor thing. I’ve a deal to do wi’ the cookin’, and there’s three men in the house besides the maister, and I can’t pretend to be much of a hand at gettin’ things up, and layin’ tables with napkins and so on. You’ll be able to do that, I des’say.” Elisabeth answered that she thought she would.

“The maister,” said Mally, “is a very particular man about them things, and he’s gotten more so lately. You see, he’s a great reader, and he’s high-larnt, and keeps very good company, and when he has onnybody here he likes his table to look smart. And, Lord love ye, I don’t know nowt about layin’ a table wi’ napkins and things, but I hope you do, my lass, I’m sure.”

“I think I can manage all that,” said Elisabeth, secretly amused at the old servant’s confession.

“Well, lass, well, I’ll answer for the cookin’, and that’s the main part, to my mind,” said Mally. “Better a bare board and plenty to eat, than a fine table wi’ nowt on it.”

With this wise remark she led the way downstairs and along a passage to a back-kitchen, in which the three men-servants to whom she had referred sat round a roaring wood fire. One of them had just returned from the statute-hiring fair, and had brought back with him a song-paper, the contents of which he was singing over to his companions. All three stared hard at Elisabeth.

“Now, then,” said Mally, “that’s Bill, and this is Tom, and yon’s Reuben. They can all ate like sojers on a march, and they keep me bakin’ every day. Reuben, hes ta filled t’ boiler?”

“Aye,” said Reuben. “Long sin’.”

“And hes ta locked t’ hen-hoil door, and browt t’ kay in?”

“Aye—aboon an hour agoöa.”

“Well, there’ll be a hot tatie for all on ye at supper-time—if ye’re good lads, mind,” said Mally, retiring with Elisabeth. “I hev’ to give ’em a bit of a treat, you know, lass,” she said apologetically, as they went back to the front-kitchen. “ ’Cos they do little jobs for me now and then. You can do owt wi’ men if ye nobbut fill their bellies.”

At nine o’clock, Mally and Elisabeth having washed up the tea-things which the former fetched from the parlour, Mally called the three men into the front-kitchen, where they sat on a bench against the wall in an attitude that suggested schoolboy-like attention. Elisabeth wondered what this might mean, and was still more mystified when Mally knocked loudly at the parlour door, and cried, “All ready, maister!” In response to her summons Hepworth presently appeared, carrying a huge Bible. He laid it on the table in the centre of the kitchen, and opening it, read a chapter from the New Testament. Elisabeth, who had never been present at such a service, listened curiously as he read. He had a full, deep voice, and read with some artistic perception, and the three men on the kitchen bench seemed to enjoy the reading, and kept their eyes fixed on their master’s face. As soon as the chapter was finished Hepworth closed the book and stood up. The three men said, “Good-night, maister,” and stamped away down the passage.

“Now, Mally,” said Hepworth, coming over to the fireside. “You’ll see after Elisabeth, I’m sure. You’ll know what she’ll—”

“Go your ways, maister,” said Mally. “Leave women-folk to see to theirsens. Men’s nobbut in the way at t’ best o’ times.”

Hepworth laughed, and bidding the two women good-night, went back to his parlour.

“Now, lass,” said Mally, “we’ll hev’ a bit o’ supper, and then to bed. ‘Early to sleep and early to rise,’ you know, and I’m a rare un for getting up wi’ the lark.”

“I should like to set the table for Mr. Hepworth’s breakfast in the morning,” said Elisabeth. “What time will he have it?”

“He’s up at six, lass, and he’s out till seven, and about half-past he’s ready and keen,” said Mally. “Aye, you can wait on him—it’ll tak’ a deal off my shoulders.” Accordingly, Elisabeth rose early next morning and proceeded to prepare the parlour for her master’s breakfast. It was a somewhat old-fashioned and gloomy apartment, sadly in need of a touch of brightness here and there. Elisabeth reduced it to something like homeliness, and laid the breakfast-table with care and taste. She hunted out a fine linen-cloth, and going out into the garden cut a bunch of chrysanthemums and arranged them in a china bowl in the centre of the table. This done, she borrowed a clean white apron from Mally, and looked very neat and smart when she carried Hepworth’s breakfast into the parlour. Hepworth smiled approval.

“That looks very nice, Elisabeth,” said he. “I see you know one part of your duties, at any rate.”

In the eyes of most people thereabouts Hepworth was a man of some peculiarity. He had now reached the age of forty years, and was known to be well-to-do even to the verge of affluence, and yet he had never shown any desire to marry and settle down after the accustomed fashion of country folk. While his mother lived there had been excuses found for him. It was said that he was such a good son that he would not share his devotion between her and a wife. Certainly he devoted himself to her with a constancy and affection that was rare. She was an invalid for many years before her death, and in Hepworth she found a tender nurse. In him, so far as she was concerned, were united feminine gentleness and masculine pity. The country folk made his devotion a proverb, and thought well of him for the manifesting of qualities which are always esteemed by people who are chiefly influenced by their natural environment, and who accordingly esteem the domestic virtues at a high standard. When the old mother died, however, it was usually supposed that Hepworth would soon give a new mistress to the Home Farm. Certainly he had never shown any partiality for any particular person of the opposite sex, and there was therefore no one’s name that could be coupled with his own. Young women there were plenty, a Jane here, and a Susan there, who would make excellent wives for a farmer, and it was thought that upon one or other of these he would shortly look with favour. He was at that time but thirty years old—an age which country folk deem a suitable one for marriage—and it seemed unnatural that so prosperous and healthy a man should not take a wife to himself. As the years passed by and he made no sign and showed no liking for female society, it was said that he was taking a long time to pick and choose; now that ten years had gone and he still remained single, some of his neighbours began to think that there was to be neither choosing nor picking, and logically enough they considered his behaviour peculiar. It was not according to tradition, which is the main rule of life amongst a conservative people.

If Hepworth had cared to confess the truth to any of his few friends, he would have told them that he refrained from marriage and even from the thought of marriage for one simple and amply sufficient reason. He had never known what it was to have any feeling of love for woman. Filial affection he knew to its deepest possibilities and would never forget, for he had worshipped his mother as a saint, and retained of her memories and impressions that were nothing short of sacred. But of actual passion, the strong, healthy, not-to-be-resisted desire of man for woman, he knew nothing—there had been nothing in his life so far to call it into existence. From boyhood he had led an active life; at fifteen he was called upon to assist his mother in superintending the affairs of the farm, and it had been necessary for many years that he should not only superintend the labour of others, but also engage in labour with his own hands. He had risen early and worked till sunset, and if he was not then too tired for aught but sleep, he devoted himself to books, for which he had a passion as great as for the brown acres that he tilled. All his life, then, had been devoted to work, to books, and to his mother, and when the companionship of his mother was taken from him, he turned to his books and to his work with renewed zest, finding in them a true and real consolation. One other factor remained in the solitude of his surroundings. In his farmstead he was almost a hermit. One other farm-house and a row of cottages made up with his own house the hamlet in which he lived. There was one village a mile-and-a-half away, and another nearly three miles distant, in which he might have found society had he cared to seek it, but the solitude in which he had mainly lived had exerted its full force on his mind, which was naturally receptive, and as he grew older he found that he was happier with his own thoughts for company than when in the society of men and women.

Nevertheless, there were occasions on which Hepworth went into the world. On market and fair days he mixed with men, and transacted his business in a fashion that showed him to be keenly alive to his own interests. He was a scrupulously fair dealer, but was not to be over-reached or deceived. Those who knew him as farmer and business man spoke highly and admiringly of his capabilities; he was, they said, the man to make money and to keep it. But in addition to being a strict man of business, Hepworth was also a man of religion. His ancestors for three generations had been devout and fervent Methodists, and in the peculiar tenets and dogmas of that body his mother had instructed him from infancy. His earliest acquaintance with religious literature came from the writings of Wesley and his contemporary apostles. With the Jewish scriptures he was intimate to a strange degree, and their poetry, their imagination, and their mystic influence had tended to fill his mind with something of the awful and mysterious. Never in a position to doubt the accuracy of all that had been taught to him, he accepted the whole creed of historic Christianity with something like childlike confidence. To him there was nothing questionable, nothing impossible in what he believed to be the scheme of salvation. It was a vast, magnificent poem, in which justice and mercy were blended with infinite love. He had never considered it from outside, for underneath its shadow he had always dwelt. When he was still a young man, Hepworth, moved thereto by certain impulses of his own nature and persuaded by his mother and the ministers at Sicaster, began to preach in the village chapels. There were other farmers in the neighbourhood who were occupied on Sundays in the same work. These he soon out-distanced in the path of popular appreciation, though he knew nothing of the fact himself. To hear him preach to his rustic audiences was to catch some notion of the mysterious tragedy of the world. When he escaped from himself into the region of prophecy he was half-poet and half-seer. He saw behind the veil, and the people saw with him. His lonely communings amongst the woods and fields, and his solitary pilgrimages to the distant villages where he had preaching engagements to fulfil, tended to develop in him the mysticism which had been planted in his nature by his early training, and it thus came about that when he spoke to the people his utterances came as from the hill-tops and the lonely places.

At the time of Elisabeth’s coming to the Home Farm, Hepworth was living his usual quiet and solitary life. He was entirely occupied with his farming, his books and his thoughts. He was in all respects a serious and sober man, taking the colour of his life from the quiet tints that surrounded him on every side, and there was no thought of change within him. Elisabeth, who at that time had much trouble of her own, thought him the loneliest man she had ever known. He ate his meals in loneliness, he went about his farm in loneliness, and he sat alone in his parlour through the long winter evenings reading his books. He rarely conversed with any of his servants, except upon matters of business. It seemed to her that he was wrapped up in himself.

Hepworth had been attracted to Elisabeth in the hiring-fair at Sicaster by the pathetic hopelessness of her face. He felt sure that she had some secret trouble, and stood in need of help. Now that she was under his roof he watched her narrowly. Within a few days of her coming there he found that she was able to accomplish all that he had engaged her to do. She was neat, orderly, and precise, and displayed the qualities of taste and management which he desired. His table was now well-ordered, and his rooms made more habitable: he felt that if occasion arose he could bring a friend or a customer to dine with him, and count upon finding things as he wished them to be. He had a certain native taste about the details of daily life which his loneliness had developed into fads and fancies that were utterly puzzling to old Mally, whose ideas were all of the rough-and-ready order. Elisabeth satisfied him in these respects: he quickly decided that he had done well in engaging her.

Though he had never paid much attention to women, Hepworth found himself studying Elisabeth with some curiosity. He quickly became aware that she was of a superior class to that from which domestic servants are usually drawn, and that there was about her a certain refinement that gave her some claim to distinction. Now that she was constantly within his view he saw that she was an engaging young woman, with a face that had even pretensions to beauty. She was always neat and tidy, and conveyed an impression of quiet resource, as she moved about her household duties. Hepworth fancied that the first week of her residence at the farm improved her personal appearance, and that some colour was beginning to come into her pale cheeks. In spite of this, however, Elisabeth’s eyes and mouth were still sad, and the pathetic look which had struck him when he first caught sight of her, remained there, and was rarely chased away.

Hepworth stood by his hearth one morning, watching Elisabeth arrange his breakfast-table. She was unaware of the scrutiny he bestowed upon her, and moved about, unconscious that he followed every detail of her work.

“You do your work very well, Elisabeth,” said Hepworth, after a time. “I am very pleased with you.”

Elisabeth looked up and coloured slightly at this word of praise.

“I am very glad, sir,” she answered.

“I don’t think you have been used to that sort of work,” he said, somewhat diffidently. “At least, not to do it yourself.”

Elisabeth made no answer.

“I hope you are quite comfortable here,” he said. “Old Mally is rather rough, I know, and perhaps you—”

Elisabeth interrupted him hastily.

“I am very comfortable, sir, indeed I am—and Mally is very kind to me,” she said. “Nobody could be kinder—and I’m glad I give you satisfaction. It was very good of you to engage me as you did—I wanted some help badly enough!” she added, with a sudden burst of confidence.

“Yes?” said Hepworth. “Then I am glad, very glad, Elisabeth. And if—perhaps I could help you further?”

Elisabeth shook her head.

“No, sir, thank you. I am much obliged to you, but you can’t.”

“You have had trouble, Elisabeth, you told me that, I think?”

“Yes, sir. But—it’s no use, sir, I can’t talk about it. It was more than trouble, and sometimes—”

She seemed to be about to say more, but suddenly stopped and hurried from the room. Hepworth looked after her with curiosity, not unmixed with pity. He wished that he had not spoken to her—it was evident that whatever trouble she had was still keen and poignant. He had supposed that it referred to the death of her husband—that much she had told him—but her last words seemed to suggest something further in the nature of mystery.

On the second Sunday after Elisabeth’s arrival at the farm, Mally informed her that Mr. Hepworth was to preach at the chapel of the neighbouring village that afternoon, and invited her to be present.

“You didn’t stir out o’ t’ house last Sunday,” said Mally, “but you mun göa to-däay, my lass, for it’ll do you good. T’ maister’s a varry high-larnt man, and I don’t reckon to understand all ’at he says, mysen, but I’m sure it’s good, ’cos he uses sich long words. I’ll get all t’ work done i’ good time efter dinner and göa wi’ you to hear him.”

Accordingly Mally and Elisabeth set out for the village chapel early in the afternoon. The old servant was attired in her Sunday best, and was proud and pleased in consequence. She drew Elisabeth’s attention to its gorgeousness as she aired each garment before the kitchen fire.

“I bowt this here gown piece,” said Mally, “seven year agoöa at Cornchester fair, and I’ve kept it for best iver sin’. That theer jacket, now—I bowt that at t’ best shop i’ Sicaster when t’ owd missis died. It hed crape trimming then, but I tuke ’em off, and Polly Jones, ’at lives at Hornforth, an’s larnin’ t’ dressmakin’ at Sicaster, she’s retrimmed it wi’ black braid i’ what she called t’ milintary fashion—summat ’at t’ sodgers weer, I reckon. I allus did believe i’ bein’ smart, you knaw. Now what do you think to my bonnet?—I’ve nobbut hed it fower year, so it’s quite in t’ fashion, as t’ saying goes.”

Elisabeth looked at the bonnet and said it was very nice. It was large and prodigal of design and colour, and Mally drew her attention to the fact that there were no less than eight sorts of flowers in it, to say nothing of a humming-bird perched at the top of an artificial spray of some tropical plant.

“It’s a bit heavy, to be sewer,” said Mally. “But Lord love ye, everybody knows ’at pride’s painful. If ye want to be i’ t’ fashion you mun mak’ up your mind to be a bit uncomfortable.”

They then set out for the chapel along the road which Elisabeth had travelled with Hepworth as they returned from Sicaster after the statute-hiring fair. Mally carried a hymn-book in one hand and a clean pocket-handkerchief, scented with dried lavender, in the other. She informed Elisabeth that she had a paper of mint lozenges in her pocket, and that she never went to chapel without them.

“There’s nowt like heyin’ summat to suck at,” she said. “When t’ preycher’s busy wi’ his firstly and secondly I can bide, but when he comes to t’ thirdly and lastly I mun hev’ summat i’ my mouth, or else I get fidgety. So if tha’ wants a lozenge, lass, tha’ mun nudge my elbow, and I’ll gi’ thi one.”

The village chapel stood near the entrance to the long street of farmsteads and cottages, and upon a slight eminence, approached by a winding path, up which several persons were slowly climbing as Mally and Elisabeth drew near. It was a quaint, four-square erection of red brick, that had been worn to a deep colour by the rain and storm of nearly a century. Above its narrow doorway a tablet of sandstone had been cemented to the wall, apparently in readiness for an inscription which was never placed there. Before the door a tiny yard or enclosure, thickly carpeted with long grass, made an open-air vestibule to the chapel. Two or three ancient men, clad in antiquated garments of sombre hue, stood about the grass, and greeted the old servant with brotherly affection. They enquired if Mr. Hepworth was coming behind.

“He’ll nooän be so long,” said Mally. “I’ll warrant him. Ye niver fun’ him late, I know. He doesn’t waste nöa time, doesn’t t’ maister, neyther at t’ fore-end nor at t’ back-end. There’s some ’at comes sweeätin’ an’ fussin’ at t’ last minute, and there’s some ’at’s theer haäf-an-hour afore t’ time, and he doesn’t belong to eyther o’ that lot. There’s some on ye hings round this chapel-door for an hour afore t’ meetin’, same as if ye’d nowt to do. Why don’t ye go inside and read t’ hymns ovver?”

With this admonition Mally passed into the chapel, followed by Elisabeth, who had never had such an experience before, and who was consequently interested in all that she heard and saw. She looked round her with curious eyes after they had taken their seats. She found herself in a square box, painted in a dull drab colour, and furnished with a hard, uncushioned seat, on which it was impossible to do otherwise than sit erect. Behind her rose four more lines of similar enclosures, with a gangway in the middle; before her lay the floor of the chapel, furnished with long, unbacked benches. Facing benches and pews stood the pulpit, a square box, approached by a short flight of stairs, and furnished with a scarlet cushion on which reposed a large Bible and a hymn-book. Everything was sombre and plain in outline and tint; the candlesticks, socketed into the tops of the pews, were of unvarnished iron, and the candles were ordinary tallow.

The chapel was already half-filled with people, and Elisabeth regarded them with some curiosity. In the pews sat two or three men of the farmer class, in broadcloth and clean linen, with their wives and families ranged in order of precedence. Two or three old folks sat on the bench by the fire with their backs against the wall, a dozen children sat here and there on the unbacked benches; a group of shock-headed ploughboys occupied the seats under the pulpit. A little woman in a poke-bonnet and large spectacles sat amongst the children and kept them in order; her sharp eyes were now fixed through her spectacles upon her hymn-book and now over them at some delinquent who showed a disposition to misbehave. In the pews and on the benches there was a peculiar silence that seemed oppressive. Now and then somebody sighed—the long sigh of abstracted meditation. It seemed to Elisabeth that everybody had retired from the world to give themselves up in this quiet little place to reflection and dreamy thought.

Presently the old men who had been waiting his arrival at the door came in with Hepworth, followed by a number of people who had lingered outside until the hour of service was at hand. Hepworth took off his overcoat and ascended the pulpit-stairs. He gave out two lines of a hymn, and there was a rustling of hymn-books amongst the occupants of the pews. Amongst the people sitting on the benches rose an old man, one of those who had waited Hepworth’s arrival at the door. He struck a tune in a high, quavering voice, and kept time to it with his hymn-book, and with swayings and contortions of his long, lean figure, that would have seemed ludicrous under other circumstances. All the folks joined in the singing, without regard to time or tune. Some of them got a bar or two in front, some lagged behind, but the old man persevered, rolling his eyes and waving his book until the final amen brought the performance to a close.

Elisabeth paid little attention to the devotional services which followed. The praying and the reading were constantly interrupted by ejaculations of praise and thanksgiving from the congregation; the hymns were sung after the fashion of the first. At last they were over, and Hepworth opened his Bible and gave out his text. Elisabeth forgot the high-backed, uncomfortable seat; she fixed her eyes on his face and wondered what he was going to say.

All that week Hepworth’s mind had been fixed on one subject—the sure and inevitable detection of secret sin. There had come to his knowledge a case in which a man had committed grievous wrong against a fellow-being, whereby suffering had come to many people while the wrong-doer went free and unsuspected. Years had passed, and at length, when the wicked man thought himself safe, the bolt had fallen, and God’s finger had pointed him out to the world with remorseless and clear indication of his guilt. That, said Hepworth, was justice. It was inevitable, nothing could prevent it. Men might sin, they might break law and commandment, and flatter themselves that no eye saw them and that no power could confound them, but their assurance was bound to come to naught. Sin meant death, righteousness meant life. In that there was comfort for those who had been wronged, and there was also warning for the evil-doer.

Hepworth’s eyes, watching the faces of his congregation, suddenly caught sight of Elisabeth. She was leaning forward, her face betraying rapt attention, her eyes ablaze with new interest, her cheeks aglow with excitement. Hepworth paused, something in her eyes, meeting his for the moment, struck a new train of thought. He turned away from the denunciations which he had been uttering against the wicked, and began to plead for forgiveness for them, from those whom their wickedness had brought to sorrow or shame. It was, he said, the nature of man to sin, but it was his highest quality to forgive. He watched Elisabeth’s face as he said this, it grew hard and cold, the light died away from it, the mouth became firm and rigid; it was evident that she was no longer interested or excited. But chancing to catch sight of her again as he wound up his exhortation by insisting on the sureness and certainty of punishment for the wicked, he saw that the eager look had returned, and that the interest was keen as before. He left the pulpit mystified. It seemed to him that for once at any rate he had preached to a soul which responded to more than half his thought.

Hepworth was to preach again at the evening service, and he remained in the village during the interval. Elisabeth and Mally returned home together, Mally full of quaint remarks as to her master’s learning and the bad behaviour of the children on the benches, Elisabeth silent and thoughtful.

When Hepworth came home later in the evening he found Elisabeth laying his supper-table in the parlour. He sat down and watched her, and thought that he still perceived some signs in her face of the eagerness she had shown during the sermon in the afternoon. Presently the table preparations were completed, but Elisabeth lingered. She looked doubtfully at her master.

“I should like to ask you something, sir,” she said diffidently. “It’s been on my mind ever since this afternoon.”

“What is it?” asked Hepworth.

“Do you believe all that you said this afternoon,” she asked, regarding him with curiosity plainly shown in her eyes and face. “All of it?”

Hepworth looked at her and wondered.

“Yes, of course I do, Elisabeth,” he answered. “All of it, every word.”

“You are sure that all will be made plain in the end, some day, sooner or later?”

“Yes, I am sure.”

Elisabeth shook her head.

“Don’t you believe it?” he asked presently.

“No!” she said. “No, sir, I wish I could. I wish I could believe that those who work wickedness will be punished for it, as you say they will.”

“They will,” he answered. “It’s sure and certain. It’s a consequence—you can’t have sin without punishment nor good without reward. Don’t doubt it. But”—here he paused and remembered her changed expression of the afternoon—“we must forgive those who do wickedness against us.”

The hard expression came into Elisabeth’s face again. She shook her head decidedly.

“Good people may do that, sir,” she said. “But if you had been tried—if you had seen wickedness, and felt yourself powerless to prevent it—if you saw the devil’s hand in a thing, and God did nothing to stop him—what then?”

Before Hepworth could answer this question, Elisabeth picked up her tray and left the room. It seemed as though she had not so much wished for an answer as that he should reconsider his own position.

Hepworth sat thinking matters over for some time without coming to any definite conclusion. There was some mystery in Elisabeth’s life, he finally decided, that had made more than an ordinary impression upon her, but as he was wholly in the dark respecting it he felt unable to talk to her on the subject. He wondered what her secret was, and whether she would eventually reveal it to him. Of one thing he felt assured—the mystery that she concealed had to a certain extent embittered her existence. He had watched her closely and had been struck by the prevailing sadness of her face, which ought to have expressed nothing but happiness and light-hearted feeling. She was young and should have had few cares, Hepworth thought. He knew little of sorrow himself, and was therefore not altogether fitted to judge of it in others, but he was persuaded that Elisabeth’s trouble was of an exceptional nature and was exercising a great influence upon her.

Hepworth pushed open the door and looked in.

p. 65.

During the afternoon of the next day Hepworth was passing through the upper fold when he heard the sound of a woman’s voice singing in one of the buildings. He stopped and listened wonderingly. The voice was clear and high—the tune a merry one. Everything about the farmstead at that moment was quiet and hushed—the day had reached that mystic point where the afternoon begins to melt towards evening. The men were working in the Ten-Acre; there was nobody about the place but Mally and Elisabeth and himself; therefore it must be from Elisabeth that the song came. He walked across the fold in the direction of the barn and pushed open the door and looked in. After the first glance he remained standing at the open door in some surprise and astonishment.

The barn had two doors, that at which Hepworth stood, opening from the fold, and one, exactly opposite, which gave access to the orchard. Between these doors the floor-space was covered with boards that in former days had been used as a threshing-floor. In the centre of this stood Elisabeth. She was dressed for the afternoon in a neat black dress, relieved from any suspicion of sombreness by a white muslin apron and cap. In one hand she held a measure full of grain, and she threw handfuls of this to the fowls which had followed her into the barn and now grouped themselves, feeding and clucking, at her feet. Now and then she threw a handful with wider sweep to the pigeons who strutted at the entrance to the orchard, or to the sparrows that had flown down from the bare-branched apple-trees and came timidly towards the barn-door. As she thus occupied herself she sang, but after he had caught sight of her Hepworth was not so much interested in her singing as in her face. For the first time since he had seen it the expression of grief and sorrow was gone and in its place there was life and animation. Elisabeth’s cheeks were full of colour; her eyes danced with pleasure, smiles curved her lips as she flung the grain amongst the birds at her feet: Hepworth suddenly recognised that she was a pretty and even fascinating woman. He pushed open the door and advanced into the barn: Elisabeth turned and caught sight of him. She stopped singing, and at the same moment the pigeons and sparrows, frightened by Hepworth’s entrance, flew away above the trees outside. The fowls stayed there and pecked at the stray grains with undisturbed industry. Elisabeth gave a little laugh and flung the grain which remained in the measure amongst them in a heap.

“You are busy, Elisabeth,” said Hepworth.

He stood close by and looked at her curiously. There was something new in her whole appearance, even in the way in which her colour slightly increased as she turned to him.

“I am only feeding the fowls, sir,” she answered.

“And singing,” he said.

“There’s no work in that, sir,” she replied.

“No, but I never heard you sing before—as you were going about the house, I mean,” he said, scarcely knowing what was in his mind.

“I haven’t sung for a long time,” she said.

“Then I suppose you sing to-day because you feel light-hearted,” said Hepworth. “Your song was a merry one, at any rate.”

Elisabeth laughed. There was something in the sound that seemed to jar on Hepworth’s mind; he looked more attentively at her, and found that over her face had come something of the hard expression with which he was already familiar.

“I don’t know about light-hearted, sir,” she said. “It’s such a long time since I knew what light-heartedness meant. But I’ve felt glad since yesterday—and I’m hopeful of something—and so I suppose I began singing.”

“What made you glad?” he asked, leaning against the door of the barn and watching her more intently.

Elisabeth gave him a quick look.

“What you said at the chapel, sir,” she replied. “I thought about it, and I think you’re right, and so I was pleased, because I wanted to think it before, only I never could bring my mind to it.”

“Oh,” said Hepworth. “And what was it that I said—about forgiving those who sin against us?”

Elisabeth shook her head with a decided activity.

“No, sir, no! It’s no use preaching that to me—saints might do it, but I can’t. No—it was what you said about those who do wrong in secret, thinking that they will never be found out and that they will escape punishment. You said that punishment would come to them. I wanted to believe that a long time, but I never could, and I shouldn’t now, only you seemed so certain about it.”

“Elisabeth,” said Hepworth, “why didn’t you believe it? Your ideas are new to me—I never met with them.”

Elisabeth looked at him with an air of doubtfulness.

“Perhaps, sir,” she answered, with evident simplicity, “you don’t know much of the world?”

“I am a man of middle age,” he said.

She shook her head and smiled.

“I don’t think that’s got much to do with it, sir. It all depends, doesn’t it, on how much a person’s seen of life?”

“Have you seen so much that you know these things better than I do?” he enquired.

“Oh no, sir; I don’t say that. I only say that from what I’ve seen during my life I’ve never been able to see that all you preached yesterday is true.”

Hepworth reflected. He was always curiously interested in these matters, and had an almost morbid curiosity in any question affecting the relation of the human soul to belief.

“You mean,” he said, “that you can’t reconcile your own experiences of life with the teachings of religion?”

“Yes, sir, I suppose that is how you would put it.”

“But why, Elisabeth?”

“Oh, for many reasons, sir. Now you say that God is good, and that He’s the Father of all, don’t you?”

Hepworth nodded his head.

“I suppose you believe that,” said Elisabeth, “and so did I, once, because I was never taught anything else. But afterwards I didn’t, because I couldn’t. If God was Father of everybody, couldn’t He protect those that never did anyone any harm? Wouldn’t He act like a father?”

“Yes.”

“Then why doesn’t He?” she asked with sudden fierceness. “Why, why? Why do wicked people flourish and go free, and become prosperous, and those who are innocent suffer for their wickedness? Why, sir?”

Hepworth shook his head. He was neither prepared nor able to answer such a question.

“That’s why I couldn’t believe those things,” said Elisabeth. “I heard them preached and talked about, but it wasn’t so in real life.”

“We don’t know all that God knows,” said Hepworth. “It may be that what we call evil is working for good.”

Elisabeth made an involuntary gesture of impatient dissent.

“I’m not clever enough to see that, sir,” she said. “But if you’d known what I’ve known, you’d know how I feel about it. Supposing you saw an innocent man suffer for a guilty one, and knew what pain and anguish he must suffer, and had to suffer yourself because of it, and prayed to God, oh, night and day, to make things right, and there was no answer, no answer, nothing but silence and helplessness—what then, sir?”

Hepworth stared at her in amazement. She spoke with vehemence, her bosom rose and fell as if under the influence of strong emotion, her mouth quivered pathetically as she spoke of suffering and helplessness.

“Elisabeth?” he exclaimed, forgetting his usual reserve. “You’ve been through all that yourself! What was it?”

But Elisabeth suddenly regained her composure. She had laid down the grain-measure on a sack of corn close by, while she spoke—she now picked it up and made for the barn-door.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” she said, her tone implying the recognition of the position which she occupied in Hepworth’s household. “I’ve been forgetting myself, I’m afraid, and talking too much. But you spoke kindly, and—and I’ve no friend to talk to now.”

“You can look on me as a friend,” said Hepworth. “And if you are in trouble—”

“I’ve no trouble now, sir, that can be shared or mended. It’s only the memory of one, and I shall tell it to nobody,” she said, with decision. “I’ve taken it to heart badly so far, but I’m feeling better since I heard what you said yesterday. I’ve thought that over, and I believe one thing—the wicked shall be found out.”

She uttered these words with such an expression of fervent hope, not unmixed with something like hate, that Hepworth could only remain silent and wondering. She went out of the barn, and in another moment he heard her singing as she crossed the fold.

Hepworth sat up late that night reading in his parlour, and when he went to bed the house was silent and dark. As he gained the head of the staircase and turned into the long passage that ran the length of the house, he was attracted by a gleam of light that came from a doorway. He walked down the passage towards it, thinking that someone had forgotten to turn out a lamp. He came to the open door and suddenly found that he was looking into Elisabeth’s room.

The door stood slightly ajar: Elisabeth had forgotten to secure it before retiring. By arrangement with old Mally she burned a lamp through the night. The lamp stood on a bracket just within the door, its light faint and low, but sufficiently clear to give Hepworth a partial view of the room. Without knowing it he had looked in and his eyes fell upon Elisabeth asleep, with the faint light full upon her face.

Hepworth stood still for a moment. She was sleeping quietly, her dark hair strewn about the pillow, her bosom rising and falling in regular movements, one arm thrown upward above her head. Whatever her trouble, she had lost it in sleep.

He stood and looked, and as he looked a sudden consciousness came over him. There was a new interest within him; he loved this woman whom he had met so strangely. For some days he had felt an unknown influence coming into his life; now at the sight of that innocent sleep, it suddenly burnt up within him into strong flame, and for the first time in his life Hepworth recognised the influence of passionate desire to love and to be loved. He looked and looked again, and suddenly closed the door with a gentle movement and went to his own room, full of new thoughts.

PART THE SECOND

WHERE HIGHWAYS MEET

To a man of Hepworth’s peculiar temperament the discovery which he had just made was full of the most remarkable meaning. For many days he went about his business, or sat in his lonely room thinking it over. In all his thought there was never any doubt as to his exact feeling for Elisabeth. That he loved her he felt certain; that he should continue to love her, and only her, he felt equally sure. That which he had never expected to encounter, and for which he had formerly felt no desire, had now come to him, and filled up all his life.

Being accustomed from childhood to self-examination, and to a certain introspection which he sometimes carried to the verge of morbid feeling, Hepworth at this period subjected his own emotions to a strict dissection. He found himself at forty years of age in love with a young woman who was a perfect stranger to him as regarded her history and antecedents. He wondered why he should fall in love with her. Was it some turn of her head, some note in her voice, some trick of the eye? If so, why did any of these things appeal to him? He had seen prettier women, not once, but a score of times—fresher, sweeter, more attractive. Why, if this one attracted him, did not they? He could say honestly that he had never been attracted by any woman’s physical beauty: if he had noticed it, it had been as other men notice pictures—with a passing glance that stopped at admiration. But now there was a different feeling within him. He analysed that feeling mercilessly, concealing nothing of it from his speculative mind.

“Here I am,” said he, as he walked the fields, or sat alone through the long evening, “a man of nigh on middle age, content until recently to live as lonely a life as ever a hermit could desire. I knew nothing of women—certainly I never wanted one. In the matter of love they were unknown to me. I never supposed that I should care to think of one in that way. And now here is this woman, whose sorrowful face attracted me to her at first, filling me with a new attraction. She is not a girl, I know she has been married already, and that she may have no more love to give, and yet I have a feeling for her that I never had for anything in my life. That feeling is a feeling of want. I want Her—not some other woman, but Her. I want all of Her—body, soul, mind. And now I know something that I never dreamed of till she came—I shall not be myself, my life will not be full and complete, unless she and I come together in one life.”

Hepworth continued this analysis of his own thoughts and feelings for many days, but he never arrived at any other conclusion than that which made itself evident at first. There was now a want in his life which only Elisabeth could satisfy. As he had already recognised, it was not some other woman, not woman in the abstract, but her. He made no attempt to explain this mystery to himself, but accepted it and waited.

For some weeks he said nothing to Elisabeth of the thoughts which filled his mind. They maintained their relations as master and servant, she with perfect sincerity, knowing nothing of the feeling which she had inspired, he with a sort of curious delight in being waited upon by the woman he loved. Hepworth indeed found a strange pleasure in the secrecy of his new feelings and emotions. He rarely conversed with Elisabeth save on the most ordinary topics, but he watched her occasionally as she went about her duties. The quiet and regular life of the lonely farmstead had exerted an improving influence upon her—she was by that time a well-favoured, even pretty woman, likely to catch the eye of any man with an eye for beauty. Hepworth noticed this, but paid little heed to it. He was not insensible to physical beauty, and indeed appreciated it keenly as all men who suddenly emerge from loneliness and self-inspection must, but his feeling was deeper, and could not be explained by the fact that Elisabeth had regained her pretty looks and bright eyes.

It is the fashion in these parts for the old women of the parish to band themselves together upon the morning of St. Thomas’s Day, and to go from farm to farm gathering contributions towards a general fund which is subsequently divided amongst them in equal shares. Hepworth’s farmstead being situated some distance from the nearest village, a deputation from the band came to him, walking through the snow in the early morning in order to collect his contribution. Elisabeth summoned him from the parlour when the old women arrived, and Hepworth left his breakfast to attend to them. They were three in number, and they sat on chairs before the kitchen fire warming hands and feet, and complaining of the bitter weather. One was wrapped closely in a man’s greatcoat, and had tied up her poke-bonnet about her ears with a shawl; another wore a stout piece of sacking over her shoulders; the third had encased her feet in successive layers of stout stocking, drawn over the boots, until she resembled an Esquimaux. Each rose and curtsied profoundly as Hepworth entered the kitchen.

“Now, then,” said Hepworth. “Come again, eh? Why, it isn’t a year since you were here, is it? The doorstep’ll never cool of you at this rate.”

This was a pleasantry made upon every such occasion, and each old woman laughed at it as a matter of course. Having laughed, they sighed profoundly.

“Poor folks, Mestur Hepworth, poor folks, ye know!” said one. “We mun keep t’ owd customs up for wer own sakes, ye know. T’ cowd’s that bitter, and coals is that dear, and poverty’s a sharp tooith, as the saying goes.”

“I’ll be bound you don’t know much about that, Nanny,” said Hepworth. “I expect you’ve got an old stocking-foot somewhere that’s pretty well lined, eh?”

“Nay, not me!” said Nanny. “I never see’d a real golden pound i’ my life to call my own. If I hed one somebody else allus hed a call on it.”

“Stockin’-feet mak’s poor purses,” said the second old woman. “They tak’ so much fillin’.”

“Aye, and now-a-days,” said the third, “there’s nowt to fill ’em wi’. Times is hard for poor folk.”

“Well,” said Hepworth, “I suppose you’ve all had your breakfasts and can’t eat any more, can you?”

“None o’ your fun-makkin’, maister,” said Mally, who stood by, busily engaged in cooking preparations. “Eh, dear, men are allus i’ t’ way. As if there worn’t some hot spiced ale all ready for ’em on t’ oven top.”

As the old women had already seen the hot spiced ale referred to, this was no news to them, but they, nevertheless, manifested much interest in its removal to the table by the fire, and in the spice-bread and cheese which was placed beside it. When each had laid hold of a pint-mug filled with Mally’s hot brew, they offered Hepworth their best respects, and wished him a long life.

“And if I might mak’ so bold,” said Nanny, “and I nursed you, mestur, when you was an infant in arms, I might say ’at I hope you’ll be a wed man come next Thomas’s Day.”

“That’s an important matter, Nanny,” said Hepworth. “Why do you wish it?”

“Naäy,” said Nanny, “I ha’ no opinion o’ single men—saving your presence. I like to see a man wi’ a wife and a houseful of bairns—that’s summut like. Lord bless ye, that’s what the good Book says. I went to t’ church last Sunday, and they were reading t’ Psalms—‘happy is he,’ they read, ‘ ’at hes his quiver full on ’em.’ ”

“Aye,” sighed the second old woman, “it all depends. It wor all varry weel for David to write that, ’cause he wor a king, and hed all t’ money ’at he wanted, and house-room, and all; but it’s different wi’ poor folk. I’ve hed ten i’ my time, and they tak’ a deal o’ bringing up.”

“I’ve hed twelve,” said Nanny, stoutly. “And I niver browt ’em up at all—they browt theirsens up. Bairns is like weeds—leave ’em alone, and they’ll grow apace.”

Mally now remarked that she had never heard such rubbish talked in all her born days. She was busily engaged in making pork-pies, and the old women were in her way, and the kitchen was further filled up by Hepworth and Elisabeth. She wanted each of them out of the way, and further resented the old women’s remarks as to the blessedness of the married state, for she herself had never enjoyed it. Nanny understanding this, and remembering that they looked to Mally for a pitcher of hot ale every Thomas’s Day, gave the signal for departure. Hepworth followed her to the door with the money for which they had walked so far. Old Nanny clutched the hand which held it out to her.

“Mestur,” quoth she, with an air of mysterious import, “you mun tak’ my advice about bein’ wed. You mon’t mind me, an owd woman ’at nursed you. Now, there’s a fine young woman there”—she nodded her poke-bonnet in Elisabeth’s direction—“why not wed her? Tak’ my advice, mestur—owd folk knows more nor young uns.”

Hepworth went back to his parlour and watched the three old women plodding through the snow that lay thick in the paddock. He was half inclined to be angry that people should so constantly give him advice as to his future; but Nanny’s counsel, sly and good-humoured, seemed to fit with his present mood. He stood watching Elisabeth as she cleared his table. Life with her, he thought, would suit all his tastes and inclinations. Why not tell her of all that was in his heart?

“What did you think of the old women, Elisabeth?” he asked. Elisabeth looked up from the table and smiled.

“I thought them very amusing, sir,” she answered.

“It is a custom they have hereabouts,” he said. “They come every St. Thomas’s Day. You never heard it spoken of, perhaps?”

“No, sir.”

“That shows you are not a countrywoman,” he said, smiling at her.

“No, sir, I am not—I never saw much of the country until I came here.”

“Well, how do you like the country now that you do see it? Is it lonely and quiet?”

“I think it is both quiet and lonely, sir. But then—”

“Well?”

“Some people like to be quiet and lonely—I am one of them.”

“Ah!” he said, with a certain feeling of satisfaction. “You don’t mind the loneliness—you wouldn’t object to live here—all your life, eh, Elisabeth?”

Elisabeth glanced at him curiously. From his gaze she turned to the window and looked out at the great black beech-trees rising from the white carpet of snow to the grey, monotonous sky above. There was a strange look in her eyes as she looked at him again.

“Once,” she said, with a faint emphasis on the word, “once I should have objected to such a life. The loneliness of it would have killed me. But now—”