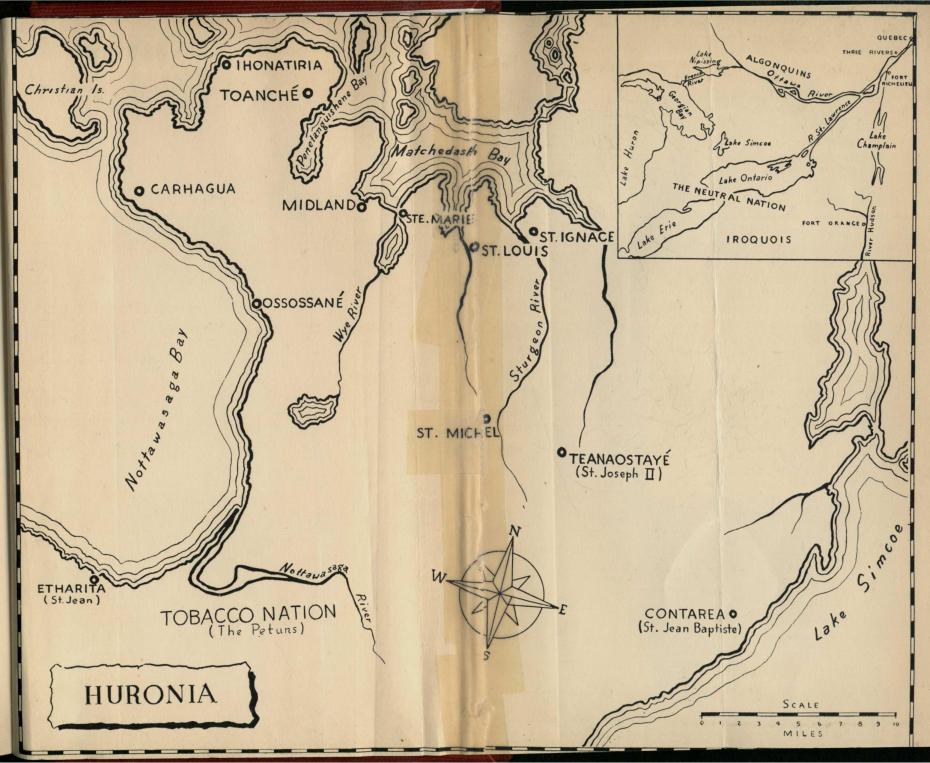

Map of Huronia

Map of Huronia

BY

E. J. PRATT

TORONTO: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF

CANADA LIMITED, AT ST. MARTIN'S HOUSE

1940

TO

MY FATHER

BREBEUF AND HIS BRETHREN

The winds of God were blowing over France,

Kindling the hearths and altars, changing vows

Of rote into an alphabet of flame.

The air was charged with song beyond the range

Of larks, with wings beyond the stretch of eagles.

Skylines unknown to maps broke from the mists

And there was laughter on the seas. With sound

Of bugles from the Roman catacombs,

The saints came back in their incarnate forms.

Across the Alps St. Francis of Assisi

In his brown tunic girt with hempen cord,

Revisited the plague-infected towns.

The monks were summoned from their monasteries,

Nuns from their convents; apostolic hands

Had touched the priests; foundlings and galley slaves

Became the charges of Vincent de Paul;

Francis de Sales put his heroic stamp

Upon his order of the Visitation.

Out of Numidia by way of Rome,

The architect of palaces, unbuilt

Of hand, again was busy with his plans,

Reshaping for the world his City of God.

Out of the Netherlands was heard the call

Of Kempis through the Imitatio

To leave the dusty marts and city streets

And stray along the shores of Galilee.

The flame had spread across the Pyrenees—

The visions of Theresa burning through

The adorations of the Carmelites;

The very clouds at night to John of the Cross

Being cruciform—chancel, transept and aisle

Blazing with light and holy oracle.

Xavier had risen from his knees to drive

His dreams full-sail under an ocean compass.

Loyola, soldier-priest, staggering with wounds

At Pampeluna, guided by a voice,

Had travelled to the Montserrata Abbey

To leave his sword and dagger on an altar

That he might lead the Company of Jesus.

The story of the frontier like a saga

Sang through the cells and cloisters of the nation,

Made silver flutes out of the parish spires,

Troubled the ashes of the canonized

In the cathedral crypts, soared through the nave

To stir the foliations on the columns,

Roll through the belfries, and give deeper tongue

To the Magnificat in Notre Dame.

It brought to earth the prophets and apostles

Out of their static shrines in the stained glass.

It caught the ear of Christ, reveined his hands

And feet, bidding his marble saints to leave

Their pedestals for chartless seas and coasts

And the vast blunders of the forest glooms.

So, in the footsteps of their patrons came

A group of men asking the hardest tasks

At the new outposts of the Huron bounds

Held in the stern hand of the Jesuit Order.

And in Bayeux a neophyte while rapt

In contemplation saw a bleeding form

Falling beneath the instrument of death,

Rising under the quickening of the thongs,

Stumbling along the Via Dolorosa.

No play upon the fancy was this scene,

But the Real Presence to the naked sense.

The fingers of Brébeuf were at his breast,

Closing and tightening on a crucifix,

While voices spoke aloud unto his ear

And to his heart—Per ignem et per aquam.

Forests and streams and trails thronged through his mind,

The painted faces of the Iroquois and Huron,

Nomadic bands and smoking bivouacs

Along the shores of western inland seas,

With forts and palisades and fiery stakes.

The stories of Champlain, Brulé, Viel,

Sagard and Le Caron had reached his town—

The stories of those northern boundaries

Where in the winter the white pines could brush

The Pleiades, and at the equinoxes

Under the gold and green of the auroras

Wild geese drove wedges through the zodiac.

The vows were deep he laid upon his soul.

"I shall be broken first before I break them."

He knew by heart the manual that had stirred

The world—the clarion calling through the notes

Of the Ignatian preludes. On the prayers,

The meditations, points and colloquies,

Was built the soldier and the martyr programme.

This is the end of man—Deum laudet,

To seek and find the will of God, to act

Upon it for the ordering of life,

And for the soul's beatitude. This is

To do, this not to do. To weigh the sin;

The interior understanding to be followed

By the amendment of the deed through grace;

The abnegation of the evil thought

And act; the trampling of the body under;

The daily practice of the counter virtues.

"In time of desolation to be firm

And constant in the soul's determination,

Desire and sense obedient to the reason."

The oath Brébeuf was taking had its root

Firm in his generations of descent.

The family name was known to chivalry—

In the Crusades; at Hastings; through the blood

Of the English Howards; called out on the rungs

Of the siege ladders; at the castle breaches;

Proclaimed by heralds at the lists, and heard

In Council Halls:—the coat-of-arms a bull

In black with horns of gold on a silver shield.

So on that toughened pedigree of fibre

Were strung the pledges. From the novice stage

To the vow-day he passed on to the priesthood,

And on the anniversary of his birth

He celebrated his first mass at Rouen.

April 26,

1625

And the first clauses of the Jesuit pledge

Were honoured when, embarking at Dieppe,

Brébeuf, Massé and Charles Lalemant

Travelled three thousand miles of the Atlantic,

And reached the citadel in seven weeks.

A month in preparation at Notre Dame

Des Anges, Brébeuf in company with Daillon

Moved to Three Rivers to begin the journey.

Taking both warning and advice from traders,

They packed into their stores of altar-ware

And vestments, strings of coloured beads with knives.

Kettles and awls, domestic gifts to win

The Hurons' favour or appease their wrath.

There was a touch of omen in the warning,

For scarcely had they started when the fate

Of the Franciscan mission was disclosed—

News of Viel, delivered to Brébeuf,—

Drowned by the natives in the final league

Of his return at Sault-au-Récollet!

Back to Quebec by Lalemant's command;

A year's delay of which Brébeuf made use

By hardening his body and his will,

Learning the rudiments of the Huron tongue,

Mastering the wood-lore, joining in the hunt

For food, observing habits of speech, the ways

Of thought, the moods and the long silences.

Wintering with the Algonquins, he soon knew

The life that was before him in the cabins—

The troubled night, branches of fir covering

The floor of snow; the martyrdom of smoke

That hourly drove his nostrils to the ground

To breathe, or offered him the choice of death

Outside by frost, inside by suffocation;

The forced companionship of dogs that ate

From the same platters, slept upon his legs

Or neck; the nausea from sagamite,

Unsalted, gritty, and that bloated feeling,

The February stomach touch when acorns,

Turk's cap, bog-onion bulbs dug from the snow

And bulrush roots flavoured with eel skin made

The menu for his breakfast-dinner-supper.

Added to this, the instigated taunts

Common as daily salutations; threats

Of murderous intent that just escaped

The deed—the prologue to Huronia!

July 1626

Midsummer and the try again—Brébeuf,

Daillon, de Nouë just arrived from France;

Quebec up to Three Rivers; the routine

Repeated; bargaining with the Indians,

Axes and beads against the maize and passage;

The natives' protest when they saw Brébeuf,

High as a totem-pole. What if he placed

His foot upon the gunwale, suddenly

Shifted an ounce of those two hundred pounds

Off centre at the rapids! They had visions

Of bodies and bales gyrating round the rocks,

Plunging like stumps and logs over the falls.

The Hurons shook their heads: the bidding grew;

Kettles and porcelain necklaces and knives,

Till with the last awl thrown upon the heap,

The ratifying grunt came from the chief.

Two Indians holding the canoe, Brébeuf,

Barefooted, cassock pulled up to his knees,

Planted one foot dead in the middle, then

The other, then slowly and ticklishly

Adjusted to the physics of his range

And width, he grasped both sides of the canoe,

Lowered himself and softly murmuring

An Ave, sat, immobile as a statue.

So the flotilla started—the same route

Champlain and Le Caron eleven years

Before had taken to avoid the swarm

Of hostile Iroquois on the St. Lawrence.

Eight hundred miles—along the Ottawa

Through the steep gorges where the river narrowed,

Through calmer waters where the river widened,

Skirting the island of the Allumettes,

Thence to the Mattawa through lakes that led

To the blue waters of the Nipissing,

And then southward a hundred tortuous miles

Down the French River to the Huron shore.

The record of that trip was for Brébeuf

A memory several times to be re-lived;

Of rocks and cataracts and portages,

Of feet cut by the river stones, of mud

And stench, of boulders, logs and tangled growths,

Of summer heat that made him long for night,

And when he struck his bed of rock—mosquitoes

That made him doubt if dawn would ever break.

'Twas thirty days to the Georgian Bay, then south

One hundred miles threading the labyrinth

Of islands till he reached the western shore

That flanked the Bay of Penetanguishene.

Soon joined by both his fellow priests he followed

The course of a small stream and reached Toanché,

Where for three years he was to make his home

And turn the first sod of the Jesuit mission.

'Twas ploughing only—for eight years would pass

Before even the blades appeared. The priests

Knew well how barren was the task should signs,

Gestures and inarticulate sounds provide

The basis of the converse. And the speech

Was hard. De Nouë set himself to school,

Unfalteringly as to his Breviary,

Through the long evenings of the fall and winter.

But as light never trickled through a sentence,

Either the Hurons' or his own, he left

With the spring's expedition to Quebec,

Where intermittently for twenty years

He was to labour with the colonists,

Travelling between the outposts, and to die

Snow-blind, caught in the circles of his tracks

Between Three Rivers and Fort Richelieu.

Daillon migrated to the south and west

To the country of the Neutrals. There he spent

The winter, fruitless. Jealousies of trade

Awoke resentment, fostered calumnies,

Until the priest under a constant threat

That often issued in assault, returned

Against his own persuasion to Quebec.

Brébeuf was now alone. He bent his mind

To the great end. The efficacious rites

Were hinged as much on mental apprehensions

As on the disposition of the heart.

For that the first equipment was the speech.

He listened to the sounds and gave them letters,

Arranged their sequences, caught the inflections,

Extracted nouns from objects, verbs from actions

And regimented rebel moods and tenses.

He saw the way the chiefs harangued the clans,

The torrent of compounded words, the art

Concealed within the pause, the look, the gesture,

Lacking all labials, the open mouth

Performed a double service with the vowels

Directed like a battery at the hearers.

With what forebodings did he watch the spell

Cast on the sick by the Arendiwans:

The sorcery of the Huron rhetoric

Extorting bribes for cures, for guarantees

Against the failure of the crop or hunt!

The time would come when steel would clash on steel,

And many a battle would be won or lost

With weapons from the armoury of words.

Three years of that apprenticeship had won

The praise of his Superior and no less

Evoked the admiration of Champlain.

That soldier, statesman, navigator, friend,

Who had combined the brain of Richelieu

With the red blood of Cartier and Magellan,

Was at this time reduced to his last keg

Of powder at the citadel. Blockade,

The piracy of Kirke on the Atlantic,

The English occupation of Quebec,

1629

And famine, closed this chapter of the Mission.

Four years at home could not abate his zeal.

Brébeuf, absorbed within his meditations,

Made ready to complete his early vows.

Each year in France but served to clarify

His vision. At Rouen he gauged the height

Of the Cathedral's central tower in terms

Of pines and oaks around the Indian lodges.

He went to Paris. There as worshipper,

His eyes were scaling transepts, but his mind,

Straying from window patterns where the sun

Shed rose ellipses on the marble floor,

Rested on glassless walls of cedar bark.

To Rennes—the Jesuits' intellectual home,

Where, in the Summa of Aquinas, faith

Laid hold on God's existence when the last

Link of the Reason slipped, and where Loyola

Enforced the high authoritarian scheme

Of God's vicegerent on the priestly fold.

Between the two nostalgic fires Brébeuf

Was swung—between two homes; in one was peace

Within the holy court, the ecstasy

Of unmolested prayer before the Virgin,

The daily and vicarious offering

On which no hand might dare lay sacrilege:

But in the other would be broken altars

And broken bodies of both Host and priest.

Then of which home, the son? From which the exile?

With his own blood Brébeuf wrote his last vow—

"Lord Jesus! You redeemed me with your blood;

By your most precious death; and this is why

I make this pledge to serve you all my life

In the Society of Jesus—never

To serve another than Thyself. Hereby

I sign this promise in my blood, ready

To sacrifice it all as willingly

As now I give this drop."—Jean de Brébeuf.

Nor did the clamour of the Thirty Years,

The battle-cries at La Rochelle and Fribourg,

Blow out the flame. Less strident than the names

Of Richelieu and Mazarin, Condé,

Turenne, but just as mighty, were the calls

Of the new apostolate. A century

Before had Xavier from the Indies summoned

The world to other colours. Now appeals

Were ringing through the history of New France.

Le Jeune, following the example of Biard

And Charles Lalemant, was capturing souls

By thousands with the fire of the Relations:

Noble and peasant, layman, priest and nun

Gave of their wealth and power and personal life.

Among his new recruits were Chastellain,

Pijart, Le Mercier, and Isaac Jogues,

The Lalemants—Jerome and Gabriel—

Jerome who was to supervise and write,

With Ragueneau, the drama of the Mission;

Who told of the survivors reaching France

When the great act was closed that "all of them

Still hold their resolution to return

To the combat at the first sound of the trumpets."

The other, Gabriel, who would share the crown

With Jean Brébeuf, pitting the frailest body

Against the hungers of the wilderness,

The fevers of the lodges and the fires

That slowly wreathed themselves around a stake.

Then Garnier, comrade of Jogues. The winds

Had fanned to a white heat the hearth and placed

Three brothers under vows—the Carmelite,

The Capuchin, and his, the Jesuit.

The gentlest of his stock, he had resolved

To seek and to accept a post that would

Transmit his nurture through a discipline

That multiplied the living martyrdoms

Before the casual incident of death.

To many a vow did Chabanel subject

His timid nature as the evidence

Of trial came through the Huronian records.

He needed every safeguard of the soul

To fortify the will, for every day

Would find him fighting, mastering his revolt

Against the native life and practices.

Of all the priests he could the least endure

The sudden transformation from the Chair

Of College Rhetoric to the heat and drag

Of portages, from the monastic calm

To the noise and smoke and vermin of the lodges,

And the insufferable sights and stinks

When, at the High Feast of the Dead, the bodies

Lying for months or years upon the scaffolds

Were taken down, stripped of their flesh, caressed,

Strung up along the cabin poles and then

Cast in a pit for common burial.

The day would come when in the wilderness,

The weary hand protesting, he would write

This final pledge—"I, Noel Chabanel,

Do vow, in presence of the Sacrament

Of Thy most precious blood and body, here

To stay forever with the Huron Mission,

According to commands of my Superiors.

Therefore I do beseech Thee to receive me

As Thy perpetual servant and to make

Me worthy of so sublime a ministry."

And the same spirit breathed on Chaumonot,

Making his restless and undisciplined soul

At first seek channels of renunciation

In abstinence, ill health and beggary.

His months of pilgrimages to the shrines

At Rome and to the Lady of Loretto,

The static hours upon his knees had sapped

His strength, turning an introspective mind

Upon the weary circuit of its thoughts,

Until one day a letter from Brébeuf

Would come to burn the torpors of his heart

And galvanize a raw novitiate.

1633

New France restored! Champlain, Massé, Brébeuf

Were in Quebec, hopes riding high as ever.

Davost and Daniel soon arrived to join

The expedition west. Midsummer trade,

The busiest the Colony had known,

Was over: forty-three canoes to meet

The hazards of return; the basic sense

Of safety, now Champlain was on the scene;

The joy of the Toanché Indians

As they beheld Brébeuf and heard him speak

In their own tongue, was happy augury.

But as before upon the eve of starting

The path was blocked, so now the unforeseen

Stepped in. A trade and tribal feud long-blown

Between the Hurons and the Allumettes

Came to a head when the Algonquin chief

Forbade the passage of the priests between

His island and the shore. The Hurons knew

The roughness of this channel, and complied.

In such delays which might have been construed

By lesser wills as exits of escape,

As providential doors on a light latch,

The Fathers entered deeper preparation.

They worked incessantly among the tribes

In the environs of Quebec, took hold

Of Huron words and beat them into order.

Davost and Daniel gathered from the store

Of speech, manners, and customs that Brébeuf

Had garnered, all the subtleties to make

The bargain for the journey. The next year

Seven canoes instead of forty! Fear

Of Iroquois following a recent raid

And massacre; growing distrust of priests;

The sense of risk in having men aboard

Unskilled in fire-arms, helpless at the paddles

And on the portages—all these combined

To sharpen the terms until the treasury

Was dry of presents and of promises.

1634

The ardours of his trip eight years before

Fresh in his mind, Brébeuf now set his face

To graver peril, for the native mood

Was hostile. On the second week the corn

Was low, a handful each a day. Sickness

Had struck the Huron, slowing down the blades,

And turning murmurs into menaces

Against the Blackrobes and their French companions.

The first blow hit Davost. Robbed of his books,

Papers and altar linens, he was left

At the Island of the Allumettes; Martin[1a]

Was put ashore at Nipissing; Baron[1b]

And Daniel were deserted, made to take

Their chances with canoes along the route,

Yet all in turn, tattered, wasted, with feet

Bleeding—broken though not in will, rejoined

Their great companion after he had reached

The forest shores of the Fresh Water Sea,

And guided by the sight of smoke had entered

The village of Ihonatiria.

[1] French assistants.

A year's success flattered the priestly hope

That on this central field seed would be sown

On which the yield would be the Huron nation

Baptized and dedicated to the Faith;

And that a richer harvest would be gleaned

Of duskier grain from the same seed on more

Forbidding ground when the arch-foes themselves

Would be re-born under the sacred rites.

For there was promise in the auspices.

Ihonatiria received Brébeuf

With joy. Three years he had been there, a friend

Whose visit to the tribes could not have sprung

From inspiration rooted in private gain.

He had not come to stack the arquebuses

Against the mountains of the beaver pelts.

He had not come to kill. Between the two—

Barter and battle—what was left to explain

A stranger in their midst? The name Echon[2]

Had solved the riddle.

[2] Echon—he who pulls the heavy load.

So with native help

The Fathers built their mission house—the frame

Of young elm-poles set solidly in earth;

Their supple tops bent, lashed and braced to form

The arched roof overlaid with cedar-bark.

"No Louvre or palace is this cabin," wrote

Brébeuf, "no stories, cellar, garret, windows,

No chimney—only at the top a hole

To let the smoke escape. Inside, three rooms

With doors of wood alone set it apart

From the single long-house of the Indians.

The first is used for storage; in the second

Our kitchen, bedroom and refectory;

Our bedstead is the earth; rushes and boughs

For mattresses and pillows; in the third,

Which is our chapel, we have placed the altar,

The images and vessels of the Mass."

It was the middle room that drew the natives,

Day after day, to share the sagamite

And raisins, and to see the marvels brought

From France—marvels on which the Fathers built

A basis of persuasion, recognizing

The potency of awe for natures nurtured

On charms and spells, invoking kindly spirits

And exorcising demons. So the natives

Beheld a mass of iron chips like bees

Swarm to a lodestone: was it gum that held

Them fast? They watched the handmill grind the corn;

Gaped at a lens eleven-faceted

That multiplied a bead as many times,

And at a phial where a captive flea

Looked like a beetle. But the miracle

Of all, the clock! It showed the hours; it struck

Or stopped upon command. Le Capitaine

Du Jour which moved its hands before its face,

Called up the dawn, saluted noon, rang out

The sunset, summoned with the count of twelve

The Fathers to a meal, or sent at four

The noisy pack of Indians to their cabins.

"What did it say?" "Yo eiouahaoua—

Time to put on the cauldron." "And what now?"

"Time to go home at once and close the door."

It was alive: an old dwelt inside,

Peering out through that black hub on the dial.

As great a mystery was writing—how

A Frenchman fifteen miles away could know

The meaning of black signs the runner brought.

Sometimes the marks were made on peel of bark,

Sometimes on paper—in itself a wonder!

From what strange tree was it the inside rind?

What charm was in the ink that transferred thought

Across such space without a spoken word?

This growing confirmation of belief

Was speeded by events wherein good fortune

Waited upon the priestly word and act.

Aug. 27,

1635

A moon eclipse was due—Brébeuf had known it—

Had told the Indians of the moment when

The shadow would be thrown across the face.

Nor was there wastage in the prayers as night,

Uncurtained by a single cloud, produced

An orb most perfect. No one knew the lair

Or nest from which the shadow came; no one

The home to which it travelled when it passed.

Only the vague uncertainties were left—

Was it the dread invasion from the south?

Such portent was the signal for the braves

To mass themselves outside the towns and shoot

Their multitudes of arrows at the sky

And fling their curses at the Iroquois.

Like a crow's wing it hovered, broodily

Brushing the face—five hours from rim to rim

While midnight darkness stood upon the land.

This was prediction baffling all their magic.

Again, when weeks of drought had parched the land

And burned the corn, when dancing sorcerers

Brought out their tortoise shells, climbed on the roofs,

Clanging their invocation to the Bird

Of Thunder to return, day after day,

Without avail, the priests formed their processions,

Put on their surplices above their robes,

And the Bird of Thunder came with heavy rain,

Released by the nine masses at Saint Joseph.

Nor were the village warriors slow to see

The value of the Frenchmen's strategy

In war. Returning from the eastern towns,

They told how soldiers had rebuilt the forts,

And strengthened them with corner bastions

Where through the embrasures enfilading fire

Might flank the Iroquois bridging the ditches,

And scaling ramparts. Here was argument

That pierced the thickest prejudice of brain

And heart, allaying panic ever present,

When with the first news of the hated foe

From scouts and hunters, women with their young

Fled to the dubious refuge of the forest

From terror blacker than a pestilence.

On such a soil tilled by those skilful hands

Those passion flowers and lilies of the East,

The Aves and the Paternosters bloomed.

The Credos and the Thou-shalt-nots were turned

By Daniel into simple Huron rhymes

And taught to children, and when points of faith

Were driven hard against resistant rock,

The Fathers found the softer crevices

Through deeds which readily the Indian mind

Could grasp—where hands were never put to blows

Nor the swift tongues used for recrimination.

Acceptance of the common lot was part

Of the original vows. But that the priests

Who were to come should not misread the text,

Brébeuf prepared a sermon on the theme

Of Patience:—"Fathers, Brothers, under call

Of God! Take care that you foresee the perils,

Labours and hardships of this Holy Mission.

You must sincerely love the savages

As brothers ransomed by the blood of Christ.

All things must be endured. To win their hearts

You must perform the smallest services.

Provide a tinder-box or burning mirror

To light their fires. Fetch wood and water for them;

And when embarking never let them wait

For you; tuck up your habits, keep them dry

To avoid water and sand in their canoes. Carry

Your load on portages. Always appear

Cheerful—their memories are good for faults.

Constrain yourselves to eat their sagamite

The way that they prepare it, tasteless, dirty."

And by the priests upon the ground all dots

And commas were observed. They suffered smoke

That billowed from the back-draughts at the roof,

Smothered the cabin, seared the eyes; the fire

That broiled the face, while frost congealed the spine;

The food from unwashed platters where refusal

Was an offence; the rasp of speech maintained

All day by men who never learned to talk

In quiet tones; the drums of the Diviners

Blasting the night—all this without complaint!

And more—whatever sleep was possible

To snatch from the occasional lull of cries

Was broken by uncovenanted fleas

That fastened on the priestly flesh like hornets.

Carving the curves of favour on the lips,

Tailoring the man into the Jesuit coat,

Wrapping the smiles round inward maledictions,

And sublimating hoary Gallic oaths

Into the Benedicite when dogs

And squaws and reeking children violated

The hours of rest, were penances unnamed

Within the iron code of good Ignatius.

Was there a limit of obedience

Outside the jurisdiction of this Saint?

How often did the hand go up to lower

The flag? How often by some ringing order

Was it arrested at the halliard touch?

How often did Brébeuf seal up his ears

When blows and insults woke ancestral fifes

Within his brain, blood-cells, and viscera,

Is not explicit in the written story.

But never could the Indians infer

Self-gain or anything but simple courage

Inspired by a zeal beyond reproof,

As when the smallpox spreading like a flame

Destroying hundreds, scarifying thousands,

The Fathers took their chances of contagion,

Their broad hats warped by rain, their moccasins

Worn to the kibes, that they might reach the huts,

Share with the sick their dwindled stock of food—

A sup of partridge broth or raisin juice,

Inscribe the sacred sign of the cross, and place

A touch of moisture from the Holy Water

Upon the forehead of a dying child.

Before the year was gone the priests were shown

The way the Hurons could prepare for death

A captive foe. The warriors had surprised

A band of Iroquois and had reserved

The one survivor for a fiery pageant.

No cunning of an ancient Roman triumph,

Nor torment of a Medici confession

Surpassed the subtle savagery of art

Which made the dressing for the sacrifice

A ritual of mockery for the victim.

What visions of the past came to Brébeuf,

And what forebodings of the days to come,

As he beheld this weird compound of life

In jest and intent taking place before

His eyes—the crude unconscious variants

Of reed and sceptre, robe and cross, brier

And crown! Might not one day baptismal drops

Be turned against him in a rain of death?

Whatever the appeals made by the priests,

They could not break the immemorial usage

Or vary one detail. The prisoner

Was made to sing his death-song, was embraced.

Hailed with ironic greetings, forced to state

His willingness to die.

"See how your hands

Are crushed. You cannot thus desire to live.

No.

Then be of good courage—you shall die.

True!—What shall be the manner of my death?

By fire."

When shall it be?

Tonight.

What hour?

At sunset.

All is well."

Eleven fires

Were lit along the whole length of the cabin.

His body smeared with pitch and bound with belts

Of bark, the Iroquois was forced to run

The fires, stopped at each end by the young braves,

And swiftly driven back, and when he swooned,

They carried him outside to the night air,

Laid him on fresh damp moss, poured cooling water

Into his mouth, and to his burns applied

The soothing balsams. With resuscitation

They lavished on him all the courtesies

Of speech and gesture, gave him food and drink,

Compassionately spoke of his wounds and pain.

The ordeal every hour was resumed

And halted, but, with each recurrence, blows

Were added to the burns and gibes gave place

To yells until the sacrificial dawn,

Lighting the scaffold, dimming the red glow

Of the hatchet collar, closed the festival.

Brébeuf had seen the worst. He knew that when

A winter pack of wolves brought down a stag

There was no waste of time between the leap

And the business click upon the jugular,

Such was the forthright honesty in death

Among the brutes. They had not learned the sport

Of dallying around the nerves to halt

A quick despatch. A human art was torture,

Where Reason crept into the veins, mixed tar

With blood and brewed its own intoxicant.

Brébeuf had pleaded for the captive's life,

But as the night wore on, would not his heart,

Colliding with his mind, have wished for death?

The plea refused, he gave the Iroquois

The only consolation in his power.

He went back to his cabin, heavy in heart.

To stem that viscous melanotic current

Demanded labour, time, and sacrifice.

Those passions were not altered over-night.

Two plans were in his mind—the one concerned

The seminary started in Quebec.

The children could be sent there to be trained

In Christian precepts, weaned from superstition

And from the savage spectacle of death.

He saw the way the women and their broods

Danced round the scaffold in their exaltation.

How much of this was habit and how much

Example? Curiously Brébeuf revolved

The facets of the Indian character.

A fighting courage equal to the French—

It could be lifted to crusading heights

By a battle speech. Endurance was a code

Among the braves, and impassivity.

Their women wailing at the Feast of Death,

The men sat silent, heads bowed to the knees.

"Never in nine years with but one exception,"

Wrote Ragueneau, "did I see an Indian weep

For grief." Only the fires evoked the cries,

And these like scalps were triumphs for the captors.

But then their charity and gentleness

To one another and to strangers gave

A balance to the picture. Fugitives

From villages destroyed found instant welcome

To the last communal share of food and land.

Brébeuf's stay at Toanché gave him proof

Of how the Huron nature could respond

To kindness. But last night upon that scaffold!

Could that be scoured from the heart? Why not

Try out the nurture plan upon the children

And send the boys east, shepherded by Daniel?

The other need was urgent—labourers!

The villages were numerous and were spread

Through such a vast expanse of wilderness

And shore. Only a bell with a bronze throat

Must summon missionaries to these fields.

With the last cry of the captive in his ears,

Brébeuf strode from his cabin to the woods

To be alone. He found his tabernacle

Within a grove, picked up a stone flat-faced,

And going to a cedar-crotch, he jammed

It in, and on this table wrote his letter.

"Herein I show you what you have to suffer.

I shall say nothing of the voyage—that

You know already. If you have the courage

To try it, that is only the beginning,

For when after a month of river travel

You reach our village, we can offer you

The shelter of a cabin lowlier

Than any hovel you have seen in France.

As tired as you may be, only a mat

Laid on the ground will be your bed. Your food

May be for weeks a gruel of crushed corn

That has the look and smell of mortar paste.

This country is the breeding place of vermin.

Sandflies, mosquitoes haunt the summer months.

In France you may have been a theologian,

A scholar, master, preacher, but out here

You must attend a savage school; for months

Will pass before you learn even to lisp

The language. Here barbarians shall be

Your Aristotle and Saint Thomas. Mute

Before those teachers you shall take your lessons.

What of the winter? Half the year is winter.

Inside your cabins will be smoke so thick

You may not read your Breviary for days.

Around your fireplace at mealtime arrive

The uninvited guests with whom you share

Your stint of food. And in the fall and winter,

You tramp unbeaten trails to reach the missions,

Carrying your luggage on your back. Your life

Hangs by a thread. Of all calamities

You are the cause—the scarcity of game,

A fire, famine or an epidemic.

There are no natural reasons for a drought

And for the earth's sterility. You are

The reasons, and at any time a savage

May burn your cabin down or split your head.

I tell you of the enemies that live

Among our Huron friends. I have not told

You of the Iroquois our constant foes.

Only a week ago in open fight

They killed twelve of our men at Contarca,

A day's march from the village where we live.

Treacherous and stealthy in their ambuscades,

They terrorize the country, for the Hurons

Are very slothful in defence, never

On guard and always seeking flight for safety.

"Wherein the gain, you ask, of this acceptance?

There is no gain but this—that what you suffer

Shall be of God: your loneliness in travel

Will be relieved by angels overhead;

Your silence will be sweet for you will learn

How to commune with God; rapids and rocks

Are easier than the steeps of Calvary.

There is a consolation in your hunger

And in abandonment upon the road,

For once there was a greater loneliness

And deeper hunger. As regards the soul

There are no dangers here, with means of grace

At every turn, for if we go outside

Our cabin, is not heaven over us?

No buildings block the clouds. We say our prayers

Freely before a noble oratory.

Here is the place to practise faith and hope

And charity where human art has brought

No comforts, where we strive to bring to God

A race so unlike men that we must live

Daily expecting murder at their hands,

Did we not open up the skies or close

Them at command, giving them sun or rain.

So if despite these trials you are ready

To share our labours, come; for you will find

A consolation in the cross that far outweighs

Its burdens. Though in many an hour your soul

Will echo—'Why hast Thou forsaken me,'

Yet evening will descend upon you when,

Your heart too full of holy exultation,

You call like Xavier—'Enough, O Lord!'"

This letter was to loom in history,

For like a bulletin it would be read

In France, and men whose bones were bound for dust

Would find that on those jagged characters

Their names would rise from their oblivion

To flame on an eternal Calendar.

Already to the field two young recruits

Had come—Pijart, Le Mercier; on their way

Were Chastellain with Garnier and Jogues

Followed by Ragueneau and Du Peron.

On many a night in lonely intervals,

The priest would wander to the pines and build

His oratory where celestial visions

Sustained his soul. As unto Paul and John

Of Patmos and the martyr multitude

The signs were given—voices from the clouds,

Forms that illumined darkness, stabbed despair,

Turned dungeons into temples and a brand

Of shame into the ultimate boast of time—

So to Brébeuf had Christ appeared and Mary.

One night at prayer he heard a voice command—

"Rise, Read!" Opening the Imitatio Christi,

His eyes "without design" fell on the chapter,

Concerning the royal way of the Holy Cross,

Which placed upon his spirit "a great peace".

And then, day having come, he wrote his vow—

"My God, my Saviour, I take from your hand

The cup of your sufferings. I invoke your name;

I vow never to fail you in the grace

Of martyrdom, if by your infinite mercy

You offer it to me. I bind myself,

And when I have received the stroke of death,

I will accept it from your gracious hand

With all pleasure and with joy in my heart;

To you my blood, my body and my life."

The labourers were soon put to their tasks,—

The speech, the founding of new posts, the sick:

Ihonatiria, a phantom town,

Through plague and flight abandoned as a base,

The Fathers chose the site—Teanaostayé,

To be the second mission of St. Joseph.

But the prime hope was on Ossossané,

A central town of fifty cabins built

On the east shore of Nottawasaga Bay.

The native council had approved the plans.

The presence of the priests with their lay help

Would be defence against the Iroquois.

Under the supervision of Pijart

The place was fortified, ramparts were strengthened,

And towers of heavy posts set at the angles.

And in the following year the artisans

And labourers from Quebec with Du Peron,

Using broad-axe and whipsaw built a church,

The first one in the whole Huronian venture

To be of wood. Close to their lodge, the priests

Dug up the soil and harrowed it to plant

A mere handful of wheat from which they raised

A half a bushel for the altar bread.

From the wild grapes they made a cask of wine

For the Holy Sacrifice. But of all work

The hardest was instruction. It was easy

To strike the Huron sense with sound and colour—

The ringing of a bell; the litanies

And chants; the surplices worn on the cassocks;

The burnished ornaments around the altar;

The pageant of the ceremonial.

But to drive home the ethics taxed the brain

To the limit of its ingenuity.

Brébeuf had felt the need to vivify

His three main themes of God and Paradise

And Hell. The Indian mind had let the cold

Abstractions fall: the allegories failed

To quicken up the logic. Garnier

Proposed the colours for the homilies.

The closest student of the Huron mind,

He had observed the fears and prejudices

Haunting the shadows of their racial past;

Had seen the flaws in Brébeuf's points; had heard

The Indian comments on the moral law

And on the Christian scheme of Paradise.

Would Iroquois be there? Yes, if baptized.

Would there be hunting of the deer and beaver?

No. Then starvation. War? And Feasts? Tobacco?

No. Garnier saw disgust upon their faces,

And sent appeals to France for pictures—one

Only of souls in bliss: of âmes damnées

Many and various—the horned Satan,

His mastiff jaws champing the head of Judas;

The plummet fall of the unbaptized pursued

By demons with their fiery forks; the lick

Of flames upon a naked Saracen;

Dragons with scarlet tongues and writhing serpents

In ambush by the charcoal avenues

Just ready at the Judgment word to wreak

Vengeance upon the unregenerate.

The negative unapprehended forms

Of Heaven lost in the dim canvas oils

Gave way to glows from brazier pitch that lit

The visual affirmatives of Hell.

Despite the sorcerers who laid the blame

Upon the French for all their ills—the plague,

The drought, the Iroquois—the Fathers counted

Baptisms by the hundreds, infants, children

And aged at the point of death. Adults

In health were more intractable, but here

The spade had entered soil in the conversion

Of a Huron in full bloom and high in power

And counsel, Tsiouendaentaha

Whose Christian name—to aid the tongue—was Peter.

Being the first, he was the Rock on which

The priests would build their Church. He was baptized

With all the pomp transferable from France

Across four thousand miles combined with what

A sky and lake could offer, and a forest

Strung to the aubade of the orioles.

The wooden chapel was their Rheims Cathedral.

In stole and surplice Lalemant intoned—

"If therefore thou wilt enter into life,

Keep the commandments. Thou shalt love the Lord

Thy God with all thy heart, with all thy soul,

With all thy might, and thy neighbour as thyself."

With salt and water and the holy chrism,

And through the signs made on his breast and forehead

The Huron was exorcised, sanctified,

And made the temple of the Living God.

The holy rite was followed by the Mass

Before the motliest auditory known

In the annals of worship. Oblates from Quebec,

Blackrobes, mechanics, soldiers, labourers,

With almost half the village packed inside,

Or jammed with craning necks outside the door.

The warriors lean, lithe, and elemental,

"As naked as your hand"[1] but for a skin

Thrown loosely on their shoulders, with their hair

Erect, boar-brushed, matted, glued with the oil

Of sunflower larded thickly with bear's grease;

Papooses yowling on their mothers' backs,

The squatting hags, suspicion in their eyes,

Their nebulous minds relating in some way

The smoke and aromatics of the censer,

The candles, crucifix and Latin murmurs

With vapours, sounds and colours of the Judgment.

[1] Lalemant's phrase.

(The Founding of Fort Sainte Marie)

1639

The migrant habits of the Indians

With their desertion of the villages

Through pressure of attack or want of food

Called for a central site where, undisturbed

The priests with their attendants might pursue

Their culture, gather strength from their devotions,

Map out the territory, plot the routes,

Collate their weekly notes and write their letters.

The roll was growing—priests and colonists,

Lay brothers offering services for life.

For on the ground or on their way to place

Themselves at the command of Lalemant,

Superior, were Claude Pijart, Poncet,

Le Moyne, Charles Raymbault, René Menard

And Joseph Chaumonot: as oblates came

Le Coq, Christophe Reynaut, Charles Boivin,

Couture and Jean Guérin. And so to house

Them all the Residence—Fort Sainte Marie!

Strategic as a base for trade or war

The site received the approval of Quebec,

Was ratified by Richelieu who saw

Commerce and exploration pushing west,

Fulfilling the long vision of Champlain—

"Greater New France beyond those inland seas."

The fort was built, two hundred feet by ninety,

Upon the right bank of the River Wye:

Its north and eastern sides of masonry,

Its south and west of double palisades,

And skirted by a moat, ran parallel

To stream and lake. Square bastions at the corners,

Watch-towers with magazines and sleeping posts,

Commanded forest edges and canoes

That furtively came up the Matchedash,

And on each bastion was placed a cross.

Inside, the Fathers built their dwelling house,

No longer the bark cabin with the smoke

Ill-trained to work its exit through the roof,

But plank and timber—at each end a chimney

Of lime and granite field-stone. Rude it was

But clean, capacious, full of twilight calm.

Across the south canal fed by the river,

Ringed by another palisade were buildings

Offering retreat to Indian fugitives

Whenever war and famine scourged the land.

The plans were supervised by Lalemant,

Assigning zones of work to every priest.

He made a census of the Huron nation;

Some thirty villages—twelve thousand persons.

Nor was this all: the horizon opened out

On larger fields. To south and west were spread

The unknown tribes—the Petuns and the Neutrals.

(The mission to the Petuns and Neutrals)

1641

In late November Jogues and Garnier

Set out on snow-obliterated trails

Towards the Blue Hills south of the Nottawasaga,

A thirty mile journey through a forest

Without a guide. They carried on their backs

A blanket with the burden of the altar.

All day confronting swamps with fallen logs,

Tangles of tamarack and juniper,

They made detours to avoid the deep ravines

And swollen creeks. Retreating and advancing,

Ever in hope their tread was towards the south,

Until, "surprised by night in a fir grove",

They took an hour with flint and steel to nurse

A fire from twigs, birch rind and needles of pine;

And flinging down some branches on the snow,

They offered thanks to God, lay down and slept.

Morning—the packs reshouldered and the tramp

Resumed, the stumble over mouldering trunks

Of pine and oak, the hopeless search for trails,

Till after dusk with cassocks torn and "nothing

To eat all day save each a morsel of bread",

They saw the smoke of the first Indian village.

And now began a labour which for faith

And triumph of the spirit over failure

Was unsurpassed in records of the mission.

Famine and pest had struck the Neutral tribes,

And fleeing squaws and children had invaded

The Petun villages for bread and refuge,

Inflicting on the cabins further pest

And further famine. When the priests arrived,

They found that their black cassocks had become

The symbols of the scourge. Children exclaimed—

"Disease and famine are outside." The women

Called to their young and fled to forest shelters,

Or hid them in the shadows of the cabins.

The men broke through a never-broken custom,

Denying the strangers right to food and rest.

Observing the two priests at prayer, the chief

Called out in council voice—"What are these demons

Who take such unknown postures, what are they

But spells to make us die—to finish those

Disease had failed to kill inside our cabins?"

Driven from town to town with all doors barred,

Pursued by storms of threats and flying hatchets,

The priests sought refuge through the forest darkness

Back to the palisades of Sainte Marie.

As bleak an outlook faced Brébeuf when he

And Chaumonot took their November tramp—

Five forest days—to the north shores of Erie,

Where the most savage of the tribes—the Neutrals

Packed their twelve thousand into forty towns.

Evil report had reached the settlements

By faster routes, for when upon the eve

Of the new mission Chaumonot had stated

The purpose of the journey, Huron chiefs,

Convinced by their own sorcerers that Brébeuf

Had laid the epidemic on the land,

Resolved to make the Neutral leaders agents

Of their revenge: for it was on Brébeuf,

The chieftain of the robes, that hate was centred.

They had the reason why the drums had failed

The hunt, why moose and deer had left the forest,

And why the Manitou who sends the sun

And rain upon the corn, lures to the trap

The beaver, trains the arrow on the goose,

Had not responded to the chants and cries.

The magic of the "breathings" had not cured

The sick and dying. Was it not the prayers

To the new God which cast malignant spells?

The rosary against the amulet?

The Blackrobes with that water-rite performed

Upon their children—with that new sign

Of wood or iron held up before the eyes

Of the stricken? Did the Indian not behold

Death following hard upon the offered Host?

Was not Echon Brébeuf the evil one?

Still, all attempts to kill him were forestalled,

For awe and fear had mitigated fury:

His massive stature, courage never questioned,

His steady glance, the firmness of his voice,

And that strange nimbus of authority,

In some dim way related to their gods,

Had kept the bowstrings of the Hurons taut

At the arrow feathers, and the javelin poised

And hesitant. But now cunning might do

What fear forbade. A brace of Huron runners

Were sped to the Neutral country with rich bribes

To put the priests to death. And so Brébeuf

And his companion entered the first town

With famine in their cheeks only to find

Worse than the Petun greetings—corn refused,

Whispers of death and screams of panic, flight

From incarnated plague, and while the chiefs

In closest council on the Huron terms

Voted for life or death, the younger men

Outside drew nearer to the priests, cursed them,

Spat at them while convulsive hands were clutching

At hatchet helves, waiting impatiently

The issue of that strident rhetoric

Shaking the cabin bark. The council ended,

The feeling strong for death but ruled by fears,

For if those foreign spirits had the power

To spread the blight upon the land, what could

Their further vengeance not exact? Besides,

What lay behind those regimental colours

And those new drums reported from Quebec?

The older men had qualified the sentence—

The priests at once must leave the Neutral land,

All cabins to be barred against admission,

No food, no shelter, and return immediate.

Defying threats, the Fathers spent four months,

Four winter months, besieging half the towns

In their pursuit of souls, for days their food

Boiled lichens, ground-nuts, star-grass bulbs and roots

Of the wild columbine. Met at the doors

By screams and blows, they would betake themselves

To the evergreens for shelter over-night.

And often, when the body strength was sapped

By the day's toil and there were streaks of blood

Inside the moccasins, when the last lodge

Rejected them as lepers and the welts

Hung on their shoulders, then the Fathers sought

The balm that never failed. Under the stars,

Along an incandescent avenue

The visions trembled, tender, placid, pure,

More beautiful than the doorway of Rheims

And sweeter than the Galilean fields.

For what was hunger and the burn of wounds

In those assuaging, healing moments when

The clearing mists revealed the face of Mary

And the lips of Jesus breathing benedictions?

At dawn they came back to the huts to get

The same rebuff of speech and club. A brave

Repulsed them at the palisade with axe

Uplifted—"I have had enough," he said,

"Of the dark flesh of my enemies. I mean

To kill and eat the white flesh of the priests."

So close to death starvation and assault

Had led them and so meagre of result

Were all their ministrations that they thought

This was the finish of the enterprise.

The winter ended in futility.

And on their journey home the Fathers took

A final blow when March leagued with the natives

Unleashed a northern storm, piled up the snow-drifts,

Broke on the ice the shoulder of Brébeuf,

And stumbled them for weeks before she sent

Them limping through the postern of the fort.

Upon his bed that night Brébeuf related

A vision he had seen—a moving cross,

Its upright beam arising from the south—

The country of the Iroquois: the shape

Advanced along the sky until its arms

Cast shadows on the Huron territory,

"And huge enough to crucify us all".

(The story of Jogues)

Bad days had fallen on Huronia.

A blight of harvest, followed by a winter

In which unusual snowfall had thinned out

The hunting and reduced the settlements

To destitution, struck its hardest blow

At Sainte Marie. The last recourse in need,

The fort had been a common granary

And now the bins were empty. Altar-ware,

Vessels, linens, pictures lost or damaged;

Vestments were ragged, writing paper spent.

The Eucharist requiring bread and wine,

Quebec eight hundred miles away, a war

Freshly renewed—the Iroquois (Dutch-armed

And seething with the memories of Champlain)

Arrayed against the French and Huron allies.

The priests assessed the perils of the journey,

1642

And the lot fell on Jogues to lead it. He,

Next to Brébeuf, had borne the heaviest brunt—

The Petun mission, then the following year,

The Ojibway where, after a hundred leagues,

Canoe and trail, accompanied by Raymbault,

He reached the shores of Lake Superior,

"And planted a great cross, facing it west".

The soundest of them all in legs, he gathered

A band of Huron traders and set out,

His task made double by the care of Raymbault

Whose health was broken mortally. He reached

Quebec with every day of the five weeks

A miracle of escape. A few days there,

With churches, hospitals, the Indian school

At Sillery, pageant and ritual,

Making their due impression on the minds

Of the Huron guides, Jogues with his band of forty

Packed the canoes and started back. Mohawks,

Enraged that on the east-bound trip the party

Had slipped their hands, awaited them, ambushed

Within the grass and reeds along the shore.

(The account of Jogues' capture and enslavement by

the Mohawks as taken from his letter to his Provincial,

Jean Filleau, dated August 5, 1643.)

"Unskilled in speech, in knowledge and not knowing

The precious hour of my visitation,

I beg you, if this letter chance to come

Unto your hands that in your charity

You aid me with your Holy Sacrifices

And with the earnest prayers of the whole Province,

As being among a people barbarous

In birth and manners, for I know that when

You will have heard this story you will see

The obligation under which I am

To God and my deep need of spiritual help.

Our business finished at Quebec, the feast

Of Saint Ignatius celebrated, we

Embarked for the Hurons. On the second day

Our men discovered on the shore fresh tracks

Thought by Eustache, experienced in war,

To be the footprints of our enemies.

A mile beyond we met them, twelve canoes

And seventy men. Abandoning the boats,

Most of the Hurons fled to a thick wood,

Leaving but twelve to put up the best front

We could, but seeing further Iroquois

Paddling so swiftly from the other shore,

We ceased from our defence and fled to cover

Of tree and bulrush. Watching from my shelter

The capture of Goupil and Indian converts,

I could not find it in my mind to leave them;

But as I was their comrade on the journey,

And should be made their comrade in the perils,

I gave myself as prisoner to the guard.

Likewise Eustache, always devoted, valiant,

Returned, exclaiming 'I praise God that He

Has granted me my prayer—that I should live

And die with you.' And then Guillaume Couture

Who, young and fleet, having outstripped his foe,

But finding flight intolerable came back

Of his free will, saying 'I cannot leave

My father in the hands of enemies.'

On him the Iroquois let loose their first

Assault for in the skirmish he had slain

A chief. They stripped him naked; with their teeth

They macerated his finger tips, tore off

The nails and pierced his right hand with a spear,

Couture taking the pain without a cry.

Then turning on Goupil and me they beat

Us to the ground under a flurry of fists

And knotted clubs, dragging us up half-dead

To agonize us with the finger torture.

And this was just the foretaste of our trials:

Dividing up as spoils of war our food,

Our clothes and books and vessels for the church,

They led or drove us on our six weeks' journey.

Our wounds festering under the summer sun.

At night we were the objects of their sport—

They mocked us by the plucking of our hair

From head and beard. And on the eighth day meeting

A band of warriors from the tribe on march

To attack the Richelieu fort, they celebrated

By disembarking all the captives, making

Us run the line beneath a rain of clubs.

And following that they placed us on the scaffolds,

Dancing around us hurling jests and insults.

Each one of us attempted to sustain

The other in his courage by no cry

Or sign of our infirmities. Eustache,

His thumbs wrenched off, withstood unconquerably

The probing of a stick which like a skewer

Beginning with the freshness of a wound

On the left hand was pushed up to the elbow.

And yet next day they put us on the route

Again—three days on foot and without food.

Through village after village we were led

In triumph with our backs shedding the skin

Under the sun—by day upon the scaffolds,

By night brought to the cabins where, cord-bound,

We lay on the bare earth while fiery coals

Were thrown upon our bodies. A long time

Indeed and cruelly have the wicked wrought

Upon my back with sticks and iron rods.

But though at times when left alone I wept,

Yet I thank Him who always giveth strength

To the weary (I will glory in the things

Concerning my infirmity, being made

A spectacle to God and to the angels,

A sport and a contempt to the barbarians)

That I was thus permitted to console

And animate the French and Huron converts,

Placing before their minds the thought of Him

Who bore against Himself the contradiction

Of sinners. Weak through hanging by my wrists

Between two poles, my feet not touching ground,

I managed through His help to reach the stage,

And with the dew from leaves of Turkish corn

Two of the prisoners I baptized. I called

To them that in their torment they should fix

Their eyes on me as I bestowed the sign

Of the last absolution. With the spirit

Of Christ, Eustache then in the fire entreated

His Huron friends to let no thought of vengeance

Arising from this anguish at the stake

Injure the French hope for an Iroquois peace.

Onnonhoaraton, a youthful captive,

They killed—the one who seeing me prepared

For torture interposed, offering himself

A sacrifice for me who had in bonds

Begotten him for Christ. Couture was seized

And dragged off as a slave. René Goupil,

While placing on a child's forehead the sign

Of the Cross was murdered by a sorcerer,

And then, a rope tied to his neck, was dragged

Through the whole village and flung in the River."

(The later account)

A family of the Wolf Clan having lost

A son in battle, Jogues as substitute

Was taken in, half-son, half-slave, his work

The drudgery of the village, bearing water,

Lighting the fires, and clad in tatters made

To join the winter hunt, bear heavy packs

On scarred and naked shoulders in the trade

Between the villages. His readiness

To execute his tasks, unmurmuring,

His courage when he plunged into a river

To save a woman and a child who stumbled

Crossing a bridge made by a fallen tree,

Had softened for a time his master's harshness.

It gained him scattered hours of leisure when

He set his mind to work upon the language

To make concrete the articles of Faith.

At intervals he stole into the woods

To pray and meditate and carve the Name

Upon the bark. Out of the Mohawk spoils

At the first battle he had found and hid

Two books—The Following of Christ and one

Of Paul's Epistles, and with these when "weary

Even of life and pressed beyond all measure

Above his strength" he followed the "running waters"

To quench his thirst. But often would the hate

Of the Mohawk foes flame out anew when Jogues

Was on his knees muttering the magic words,

And when a hunting party empty-handed

Returned or some reverse was met in battle,

Here was the victim ready at their door.

Believing that a band of warriors

Had been destroyed, they seized the priest and set

His day of death, but at the eleventh hour,

With the arrival of a group of captives,

The larger festival of torture gave

Him momentary reprieve. Yet when he saw

The holocaust and rushed into the flames

To save a child, a heavy weight laid hold

Upon his spirit lasting many days—

"My life wasted with grief, my years with sighs;

Oh wherefore was I born that I should see

The ruin of my people! Woe is me!

But by His favour I shall overcome

Until my change is made and He appear."

This story of enslavement had been brought

To Montmagny, the Governor of Quebec,

And to the outpost of the Dutch, Fort Orange.

Quebec was far away and, short of men,

Could never cope with the massed Iroquois,

Besides, Jogues' letter begged the Governor

That no measures "to save a single life"

Should hurt the cause of France. To the Provincial

He wrote—"Who in my absence would console

The captives? Who absolve the penitent?

Encourage them in torments? Who baptize

The dying? On this cross to which our Lord

Has nailed me with Himself am I resolved

To live and die."

And when the commandant

Of the Dutch fort sent notice that a ship

At anchor in the Hudson would provide

Asylum, Jogues delayed that he might seek

Counsel of God and satisfy his conscience,

Lest some intruding self-preserving thought

Conflict with duty. Death was certain soon.

He knew it—for that mounting tide of hate

Could not be checked: it had engulfed his friends;

'Twould take him next. How close to suicide

Would be refusal? Not as if escape

Meant dereliction: no, his early vows

Were still inviolate—he would return.

He pledged himself to God there on his knees

Before two bark-strips fashioned as a cross

Under the forest trees—his oratory.

And so, one night, the Indians asleep,

Jogues left the house, fumbling his darkened way,

Half-walk, half-crawl, a lacerated leg

Making the journey of one-half a mile

The toil of half a night. By dawn he found

The shore, and, single-handed, pushed a boat,

Stranded by ebb-tide, down the slope of sand

To the river's edge and rowed out to the ship,

Where he was lifted up the side by sailors

Who, fearful of the risk of harbouring

A fugitive, carried him to the hatch

And hid him with the cargo in the hold.

The outcry in the morning could be heard

Aboard the ship as Indians combed the cabins,

Threatened the guards and scoured the neighbouring woods,

And then with strong suspicion of the vessel

Demanded of the officers their captive.

After two days Jogues with his own consent

Was taken to the fort and hid again

Behind the barrels of a store. For weeks

He saw and heard the Mohawks as they passed,

Examining cordage, prying into casks,

At times touching his clothes, but missing him

As he lay crouched in darkness motionless.

With evidence that he was in the fort,

The Dutch abetting the escape, the chiefs

Approached the commandant—"The prisoner

Is ours. He is not of your race or speech.

The Dutch are friends: the Frenchmen are our foes.

Deliver up this priest into our hands."

The cries were countered by the officer—

"He is like us in blood if not in tongue.

The Frenchman here is under our protection.

He is our guest. We treat him as you treat

The strangers in your cabins, for you feed

And shelter them. That also is our law,

The custom of our nation." Argument

Of no avail, a ransom price was offered,

Refused, but running up the bargain scale,

It caught the Mohawks at three hundred livres,

And Jogues at last was safely on the Hudson.

The tale of Jogues' first mission to the Hurons

Ends on a sequel briefly sung but keyed

To the tune of the story, for the stretch

Home was across a wilderness, his bed

A coil of rope on a ship's open deck

Swept by December surge. The voyage closed

At Falmouth where, robbed by a pirate gang,

He wandered destitute until picked up

By a French crew who offered him tramp fare.

He landed on the shore of Brittany

On Christmas Eve, and by New Year he reached

The Jesuit establishment at Rennes.

The trumpets blew once more, and Jogues returned

With the spring expedition to Quebec.

Honoured by Montmagny, he took the post

Of peace ambassador to hostile tribes,

And then the orders came from Lalemant

That he should open up again the cause

Among the Mohawks at Ossernenon.

Jogues knew that he was travelling to his death,

And though each hour of that former mission

Burned at his finger stumps, the wayward flesh

Obeyed the summons. Lalemant as well

Had known the peril—had he not re-named

Ossernenon, the Mission of the Martyrs?

So Jogues, accompanied by his friend Lalande

Departed for the village—his last letter

To his Superior read: "I will return

Cost it a thousand lives. I know full well

That I shall not survive, but He who helped

Me by His grace before will never fail me

Now when I go to do His holy will."

And to the final consonant the vow

Was kept, for two days after they had struck

The town, their heads were on the palisades,

1646

And their dragged bodies flung into the Mohawk.

(Bressani)

The western missions waiting Jogues' return

Were held together by a scarlet thread.

The forays of the Iroquois had sent

The fugitive survivors to the fort.

Three years had passed—and where was Jogues? The scant

Supplies of sagamite could never feed

The inflow from the stricken villages.

The sparse reports had filtered to Quebec,

And the command was given to Bressani

To lead the rescue band to Sainte Marie.

Leaving Three Rivers in the spring when ice

Was on the current, he was caught like Jogues,

With his six Hurons and a French oblate,

A boy of twelve; transferred to Iroquois'

Canoes and carried up the Richelieu;

Disbarked and driven through the forest trails

To Lake Champlain; across it; and from there

Around the rocks and marshes to the Hudson.

And every time a camp was built and fires

Were laid the torment was renewed; in all

The towns the squaws and children were regaled

With evening festivals upon the scaffolds.

Bressani wrote one day when vigilance

Relaxed and his split hand was partly healed—

"I do not know if your Paternity

Will recognize this writing for the letter

Is soiled. Only one finger of the hand

Is left unburned. The blood has stained the paper.

My writing table is the earth; the ink

Gunpowder mixed with water." And again—

This time to his Superior—"I could

Not have believed it to be possible

That a man's body was so hard to kill."

The earlier fate of Jogues was his—enslaved,

But ransomed at Fort Orange by the Dutch;

Restored to partial health; sent to Rochelle

In the autumn, but in April back again

And under orders for the Huron mission,

Where he arrived this time unscathed to take

A loyal welcome from his priestly comrades.

Bressani's presence stimulated faith

Within the souls of priests and neophytes.

The stories burned like fuel of the faggots—

Jogues' capture and his rock stability,

And the no less triumphant stand Eustache

Had made showing the world that native metal

Could take the test as nobly as the French.

And Ragueneau's letter to his General stated—

"Bressani ill-equipped to speak the Huron

Has speech more eloquent to capture souls:

It is his scars, his mutilated hands.

'Only show us,' the neophytes exclaim,

'The wounds, for they teach better than our tongues

Your faith, for you have come again to face

The dangers. Only thus we know that you

Believe the truth and would have us believe it.'"

In those three years since Jogues' departure doubts

Though unexpressed had visited the mission.

For death had come to several in the fold—

Raymbault, Goupil, Eustache, and worse than death

To Jogues, and winter nights were bleaker, darker

Without the company of Brébeuf. Lion

Of limb and heart, he had entrenched the faith,

Was like a triple palisade himself.

But as his broken shoulder had not healed,

And ordered to Quebec by Lalemant,

He took the leave that seven years of work

Deserved. The city hailed him with delight.

For more than any other did he seem

The very incarnation of the age—

Champlain the symbol of exploring France,

Tracking the rivers to their lairs, Brébeuf

The token of a nobler chivalry.

He went the rounds of the stations, saw the gains

The East had made in converts—Sillery

For Indians and Notre Dame des Anges

For the French colonists; convents and schools

Flourished. Why should the West not have the same

Yield for the sowing? It was labourers

They needed with supplies and adequate

Defence. St. Lawrence and the Ottawa

Infested by the Iroquois were traps

Of death. Three bands of Hurons had been caught

That summer. Montmagny had warned the priest

Against the risk of unprotected journeys.

So when the reinforcements came from France,

Brébeuf set out under a guard of soldiers

Taking with him two young recruits—Garreau

And Chabanel—arriving at the fort

In the late fall. The soldiers wintered there

And supervised defensive strategy.

Replaced the forlorn feelings with fresh hopes,

And for two years the mission enterprise

Renewed its lease of life. Rumours of treaties

Between the French and Mohawks stirred belief

That peace was in the air, that other tribes

Inside the Iroquois Confederacy

Might enter—with the Hurons sharing terms.

This was the pipe-dream—was it credible?

The ranks of missionaries were filling up:

At Sainte Marie, Brébeuf and Ragueneau,

Le Mercier, Chastellain and Chabanel;

St. Joseph—Garnier and René Menard;

St. Michel—Chaumonot and Du Peron;

The others—Claude Pijart, Le Moyne, Garreau

And Daniel.

What validity the dream

Possessed was given by the seasonal

Uninterrupted visits of the priests

To their loved home, both fort and residence.

Here they discussed their plans, and added up

In smiling rivalry their tolls of converts:

They loitered at the shelves, fondled the books,

Running their fingers down the mellowed pages

As if they were the faces of their friends.

They stood for hours before the saints or knelt

Before the Virgin and the crucifix

In mute transfiguration. These were hours

That put the bandages upon their hurts,

Making their spirits proof against all ills

That had assailed or could assail the flesh,

Turned winter into spring and made return

To their far mission posts an exaltation.

The bell each morning called the neophytes

To Mass, again at evening, and the tones

Lured back the memories across the seas.

And often in the summer hours of twilight

When Norman chimes were ringing, would the priests

Forsake the fort and wander to the shore

To sing the Gloria while hermit thrushes

Rivalled the rapture of the nightingales.

The native register was rich in name

And number. Earlier years had shown results

Mainly among the young and sick and aged,

Where little proof was given of the root

Of faith, but now the Fathers told of deeds

That flowered from the stems. Had not Eustache

Bequeathed his record like a Testament?

The sturdiest warriors and chiefs had vied

Among themselves within the martyr ranks:—

Stories of captives led to sacrifice,

Accepting scaffold fires under the rites,

Enduring to the end, had taken grip

Of towns and clans. St. Joseph had its record

For Garnier reported that Totiri,

A native of high rank, while visiting

St. Ignace when a torture was in progress,

Had emulated Jogues by plunging through

The flaming torches that he might apply

The Holy Water to an Iroquois.

Garreau and Pijart added lists of names

From the Algonquins and the Nipissings,

And others told of Pentecostal meetings

In cabins by the Manitoulin shores.

Not only was the faith sustained by hopes

Nourished within the bosom of their home

And by the wish-engendered talk of peace,

But there outside the fort was evidence

Of tenure for the future. Acres rich

In soil extended to the forest fringe.

Each year they felled the trees and burned the stumps,

Pushing the frontier back, clearing the land,

Spading, hoeing. The stomach's noisy protest

At sagamite and wild rice found a rest

With bread from wheat, fresh cabbages and pease,

And squashes which when roasted had the taste

Of Norman apples. Strawberries in July,

October beechnuts, pepper roots for spice,

And at the bottom of a spring that flowed

Into a pond shaded by silver birches

And ringed by marigolds was water-cress

In chilled abundance. So, was this the West?

The Wilderness? That flight of tanagers;