* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Vol 5, Issue 5

Date of first publication: 1869

Author: John Townsend Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Feb. 8, 2016

Date last updated: Feb. 8, 2016

Faded Page eBook #20160209

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

LILIES OF THE VALLEY.

Drawn by Miss Jessie Curtis.] [See page 288.

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. V. | May, 1869. | No. V. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by Fields, Osgood, & Co., in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

In the course of ten days I recovered sufficiently from my injuries to attend school, where, for a little while, I was looked upon as a hero, on account of having been blown up. What don’t we make a hero of? The distraction which prevailed in the classes the week preceding the Fourth had subsided, and nothing remained to indicate the recent festivities, excepting a noticeable want of eyebrows on the part of Pepper Whitcomb and myself.

In August we had two weeks’ vacation. It was about this time that I became a member of the Rivermouth Centipedes, a secret society composed of twelve of the Temple Grammar School boys. This was an honor to which I had long aspired, but, being a new boy, I was not admitted to the fraternity until my character had fully developed itself.

It was a very select society, the object of which I never fathomed, though I was an active member of the body during the remainder of my residence at Rivermouth, and at one time held the onerous position of F. C.,—First Centipede. Each of the elect wore a copper cent (some occult association being established between a cent apiece and a centipede!) suspended by a string round his neck. The medals were worn next the skin, and it was while bathing one day at Grave Point, with Jack Harris and Fred Langdon, that I had my curiosity roused to the highest pitch by a sight of these singular emblems. As soon as I ascertained the existence of a boys’ club, of course I was ready to die to join it. And eventually I was allowed to join.

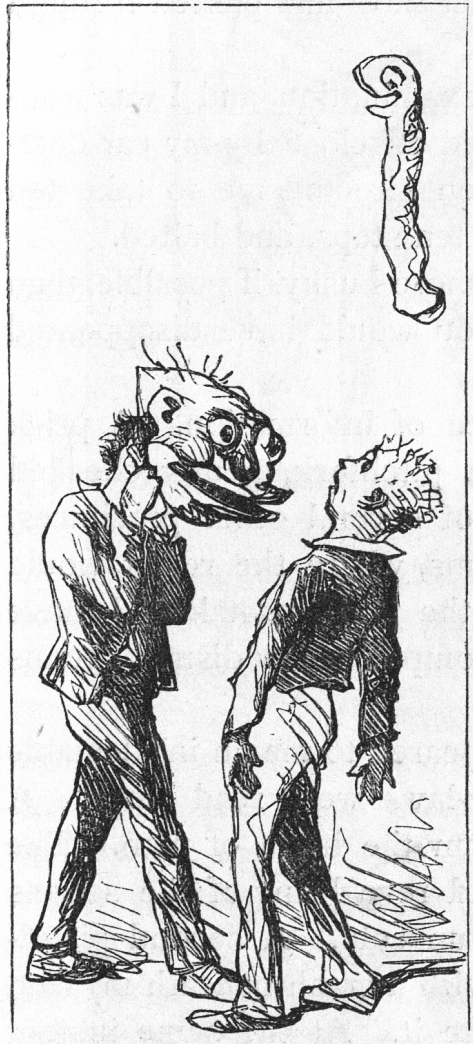

The initiation ceremony took place in Fred Langdon’s barn, where I was submitted to a series of trials not calculated to soothe the nerves of a timorous boy. Before being led to the Grotto of Enchantment,—such was the modest title given to the loft over my friend’s wood-house,—my hands were securely pinioned, and my eyes covered with a thick silk handkerchief. At the head of the stairs, I was told in an unrecognizable, husky voice, that it was not yet too late to retreat if I felt myself physically too weak to undergo the necessary tortures. I replied that I was not too weak, in a tone which I intended to be resolute, but which, in spite of me, seemed to come from the pit of my stomach.

“It is well!” said the husky voice.

I did not feel so sure about that; but, having made up my mind to be a Centipede, a Centipede I was bound to be. Other boys had passed through the ordeal and lived, why should not I?

A prolonged silence followed this preliminary examination, and I was wondering what would come next, when a pistol fired off close by my ear deafened me for a moment. The unknown voice then directed me to take ten steps forward and stop at the word halt. I took ten steps, and halted.

“Stricken mortal,” said a second husky voice, more husky, if possible, than the first, “if you had advanced another inch, you would have disappeared down an abyss three thousand feet deep!”

I naturally shrunk back at this friendly piece of information. A prick from some two-pronged instrument, evidently a pitchfork, gently checked my retreat. I was then conducted to the brink of several other precipices, and ordered to step over many dangerous chasms, where the result would have been instant death if I had committed the least mistake. I have neglected to say that my movements were accompanied by dismal groans from various parts of the grotto.

Finally, I was led up a steep plank to what appeared to me an incalculable height. Here I stood breathless while the by-laws were read aloud. A more extraordinary code of laws never came from the brain of man. The penalties attached to the abject being who should reveal any of the secrets of the society were enough to make the blood run cold. A second pistol-shot was heard, the something I stood on sunk with a crash beneath my feet, and I fell two miles, as nearly as I could compute it. At the same instant the handkerchief was whisked from my eyes, and I found myself standing in an empty hogshead surrounded by twelve masked figures fantastically dressed. One of the conspirators was really appalling with a tin saucepan on his head, and a tiger-skin sleigh-robe thrown over his shoulders. I scarcely need say that there were no vestiges to be seen of the fearful gulfs over which I had passed so cautiously. My ascent had been to the top of the hogshead, and my descent to the bottom thereof. Holding one another by the hand, and chanting a low dirge, the Mystic Twelve revolved about me. This concluded the ceremony. With a merry shout the boys threw off their masks, and I was declared a regularly installed member of the R. M. C.

I afterwards had a good deal of sport out of the club, for these initiations, as you may imagine, were sometimes very comical spectacles, especially when the aspirant for centipedal honors happened to be of a timid disposition. If he showed the slightest terror, he was certain to be tricked unmercifully. One of our subsequent devices—a humble invention of my own—was to request the candidate to put out his tongue, whereupon the First Centipede would say, in a low tone, as if not intended for the ear of the victim, “Diabolus, fetch me the red-hot iron!” The expedition with which that tongue would disappear was simply ridiculous.

Our meetings were held in various barns, at no stated periods, but as circumstances suggested. Any member had a right to call a meeting. Each boy who failed to report himself was fined one cent. Whenever a member had reasons for thinking that another member would be unable to attend, he called a meeting. For instance, immediately on learning the death of Harry Blake’s great-grandfather, I issued a call. By these simple and ingenious measures we kept our treasury in a flourishing condition, sometimes having on hand as much as a dollar and a quarter.

I have said that the society had no especial object. It is true, there was a tacit understanding among us that the Centipedes were to stand by one another on all occasions, though I don’t remember that they did; but further than this we had no purpose, unless it was to accomplish as a body the same amount of mischief which we were sure to do as individuals. To mystify the staid and slow-going Rivermouthians was our frequent pleasure. Several of our pranks won us such a reputation among the townsfolk, that we were credited with having a large finger in whatever went amiss in the place.

One morning about a week after my admission into the secret order, the quiet citizens awoke to find that the sign-boards of all the principal streets had changed places during the night. People who went trustfully to sleep in Currant Square opened their eyes in Honeysuckle Terrace. Jones’s Avenue at the north end had suddenly become Walnut Street, and Peanut Street was nowhere to be found. Confusion reigned. The town authorities took the matter in hand without delay, and six of the Temple Grammar School boys were summoned to appear before Justice Clapham.

Having tearfully disclaimed to my grandfather all knowledge of the transaction, I disappeared from the family circle, and was not apprehended until late in the afternoon, when the Captain dragged me ignominiously from the hay-mow and conducted me, more dead than alive, to the office of Justice Clapham. Here I encountered five other pallid culprits, who had been fished out of divers coal-bins, garrets, and chicken-coops, to answer the demands of the outraged laws. (Charley Marden had hidden himself in a pile of gravel behind his father’s house, and looked like a recently exhumed mummy.)

There was not a particle of evidence against us; and, indeed, we were wholly innocent of the offence. The trick, as was afterwards proved, had been played by a party of soldiers stationed at the fort in the harbor. We were indebted for our arrest to Master Conway, who had slyly dropped a hint, within the hearing of Selectman Mudge, to the effect that “young Bailey and his five cronies could tell something about them signs.” When he was called upon to make good his assertion, he was considerably more terrified than the Centipedes, though they were ready to sink into their shoes.

At our next meeting, it was unanimously resolved that Conway’s animosity should not be quietly submitted to. He had sought to inform against us in the stage-coach business; he had volunteered to carry Pettingil’s “little bill” for twenty-four ice-creams to Charley Marden’s father; and now he had caused us to be arraigned before Justice Clapham on a charge equally groundless and painful. After much noisy discussion a plan of retaliation was agreed upon.

There was a certain slim, mild apothecary in the town, by the name of Meeks. It was generally given out that Mr. Meeks had a vague desire to get married, but, being a shy and timorous youth, lacked the moral courage to do so. It was also well known that the Widow Conway had not buried her heart with the late lamented. As to her shyness, that was not so clear. Indeed, her attentions to Mr. Meeks, whose mother she might have been, were of a nature not to be misunderstood, and were not misunderstood by any one but Mr. Meeks himself.

The widow carried on a dress-making establishment at her residence on the corner opposite Meeks’s drug-store, and kept a wary eye on all the young ladies from Miss Dorothy Gibb’s Female Institute who patronized the shop for soda-water, acid-drops, and slate-pencils. In the afternoon the widow was usually seen seated, smartly dressed, at her window up stairs, casting destructive glances across the street,—the artificial roses in her cap and her whole languishing manner saying as plainly as a label on a prescription, “To be Taken Immediately!” But Mr. Meeks didn’t take.

The lady’s fondness, and the gentleman’s blindness, were topics ably handled at every sewing-circle in the town. It was through these two luckless individuals that we proposed to strike a deadly blow at the common enemy. To kill less than three birds with one stone, did not suit our sanguinary purpose. We disliked the widow not so much for her sentimentality as for being the mother of Bill Conway; we disliked Mr. Meeks, not because he was insipid, like his own sirups, but because the widow loved him; Bill Conway we hated for himself.

Late one dark Saturday night in September, we carried our plan into effect. On the following morning, as the orderly citizens wended their way to church past the widow’s abode, their sober faces relaxed at beholding over her front door the well-known gilt Mortar and Pestle which usually stood on the top of a pole on the opposite corner; while the passers on that side of the street were equally amused and scandalized at seeing a placard bearing the following announcement tacked to the druggist’s window-shutters:—

The naughty cleverness of the joke (which I should be sorry to defend) was recognized at once. It spread like wildfire over the town, and, though the mortar and the placard were speedily removed, our triumph was complete. The whole community was on the broad grin, and our participation in the affair seemingly unsuspected. It was those wicked soldiers at the Fort!

There was one person, however, who cherished a strong suspicion that the Centipedes had had a hand in the business; and that person was Conway. His red hair seemed to change to a livelier red, and his sallow cheeks to a deeper sallow, as we glanced at him stealthily over the tops of our slates the next day in school. He knew we were watching him, and made sundry mouths and scowled in the most threatening way over his sums.

Conway had an accomplishment peculiarly his own,—that of throwing his thumbs out of joint at will. Sometimes while absorbed in study, or on becoming nervous at recitation, he performed the feat unconsciously. Throughout this entire morning, his thumbs were observed to be in a chronic state of dislocation, indicating great mental agitation on the part of the owner. We fully expected an outbreak from him at recess; but the intermission passed off tranquilly, somewhat to our disappointment.

At the close of the afternoon session, it happened that Binny Wallace and myself, having got swamped in our Latin exercise, were detained in school for the purpose of refreshing our memories with a page of Mr. Andrews’s perplexingly irregular verbs. Binny Wallace, finishing his task first, was dismissed. I followed shortly after, and, on stepping into the play-ground, saw my little friend plastered, as it were, up against the fence, and Conway standing in front of him ready to deliver a blow on the upturned, unprotected face, whose gentleness would have stayed any arm but a coward’s.

Seth Rodgers, with both hands in his pockets, was leaning against the pump lazily enjoying the sport; but on seeing me sweep across the yard, whirling my strap of books in the air like a sling, he called out lustily, “Lay low, Conway! here’s young Bailey!”

Conway turned just in time to catch on his shoulder the blow intended for his head. He reached forward one of his long arms—he had arms like a windmill, that boy—and, grasping me by the hair, tore out quite a respectable handful. The tears flew to my eyes, but they were not tears of pain; they were merely the involuntary tribute which nature paid to the departed tresses.

In a second my little jacket lay on the ground, and I stood on guard, resting lightly on my right leg and keeping my eye fixed steadily on Conway’s,—in all of which I was faithfully following the instructions of Phil Adams, whose father subscribed to a sporting journal.

Conway also threw himself into a defensive attitude, and there we were, glaring at each other, motionless, neither of us disposed to risk an attack, but both on the alert to resist one. There is no telling how long we might have remained in that absurd position, had we not been interrupted.

It was a custom with the larger pupils to return to the play-ground after school, and play base-ball until sundown. The town authorities had prohibited ball-playing on the Square, and, there being no other available place, the boys fell back perforce on the school-yard. Just at this crisis, a dozen or so of the Templars entered the gate, and, seeing at a glance the belligerent status of Conway and myself, dropped bat and ball, and rushed to the spot where we stood.

“Is it a fight?” asked Phil Adams, who saw by our freshness that we had not yet got to work.

“Yes, it’s a fight,” I answered, “unless Conway will ask Wallace’s pardon, promise never to hector me in future,—and put back my hair!”

This last condition was rather a staggerer.

“I sha’n’t do nothing of the sort,” said Conway, sulkily.

“Then the thing must go on,” said Adams, with dignity. “Rodgers, as I understand it, is your second, Conway? Bailey, come here. What’s the row about?”

“He was thrashing Binny Wallace.”

“No, I wasn’t,” interrupted Conway; “but I was going to, because he knows who put Meeks’s mortar over our door. And I know well enough who did it; it was that sneaking little mulatter!”—pointing at me.

“O, by George!” I cried, reddening at the insult.

“Cool is the word,” said Adams, as he bound a handkerchief round my head, and carefully tucked away the long straggling locks that offered a tempting advantage to the enemy. “Who ever heard of a fellow with such a head of hair going into action!” muttered Phil, twitching the handkerchief to ascertain if it were securely tied. He then loosened my gallowses (braces), and buckled them tightly above my hips. “Now, then, bantam, never say die!”

Conway regarded these business-like preparations with evident misgiving, for he called Rodgers to his side, and had himself arrayed in a similar manner, though his hair was cropped so close that you couldn’t have taken hold of it with a pair of tweezers.

“Is your man ready?” asked Phil Adams, addressing Rodgers.

“Ready!”

“Keep your back to the gate, Tom,” whispered Phil in my ear, “and you’ll have the sun in his eyes.”

Behold us once more face to face, like David and the Philistine. Look at us as long as you may; for this is all you shall see of the combat. According to my thinking, the hospital teaches a better lesson than the battlefield. I will tell you about my black eye, and my swollen lip, if you will; but not a word of the fight.

You’ll get no description of it from me, simply because I think it would prove very poor reading, and not because I consider my revolt against Conway’s tyranny unjustifiable.

I had borne Conway’s persecutions for many months with lamb-like patience. I might have shielded myself by appealing to Mr. Grimshaw; but no boy in the Temple Grammar School could do that without losing caste. Whether this was just or not, doesn’t matter a pin, since it was so,—a traditionary law of the place. The personal inconvenience I suffered from my tormentor was nothing to the pain he inflicted on me indirectly by his persistent cruelty to little Binny Wallace. I should have lacked the spirit of a hen if I had not resented it finally. I am glad that I faced Conway, and asked no favors, and got rid of him forever. I am glad that Phil Adams taught me to box, and I say to all youngsters: Learn to box, to ride, to pull an oar, and to swim. The occasion may come round, when a decent proficiency in one or the rest of these accomplishments will be of service to you.

In one of the best books* ever written for boys are these words:—

“Learn to box, then, as you learn to play cricket and football. Not one of you will be the worse, but very much the better, for learning to box well. Should you never have to use it in earnest, there’s no exercise in the world so good for the temper, and for the muscles of the back and legs.

“As for fighting, keep out of it, if you can, by all means. When the time comes, if ever it should, that you have to say ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to a challenge to fight, say ‘No’ if you can,—only take care you make it plain to yourself why you say ‘No.’ It’s a proof of the highest courage, if done from true Christian motives. It’s quite right and justifiable, if done from a simple aversion to physical pain and danger. But don’t say ‘No’ because you fear a licking and say or think it’s because you fear God, for that’s neither Christian nor honest. And if you do fight, fight it out; and don’t give in while you can stand and see.”

And don’t give in when you can’t! say I. For I could stand very little, and see not at all (having pummelled the school-pump for the last twenty seconds), when Conway retired from the field. As Phil Adams stepped up to shake hands with me, he received a telling blow in the stomach; for all the fight was not out of me yet, and I mistook him for a new adversary.

Convinced of my error, I accepted his congratulations, with those of the other boys, blandly and blindly. I remember that Binny Wallace wanted to give me his silver pencil-case. The gentle soul had stood throughout the contest with his face turned to the fence, suffering untold agony.

A good wash at the pump, and a cold key applied to my eye, refreshed me amazingly. Escorted by two or three of the schoolfellows, I walked home through the pleasant autumn twilight, battered but triumphant. As I went along, my cap cocked on one side to keep the chilly air from my eye, I felt that I was not only following my nose, but following it so closely, that I was in some danger of treading on it. I seemed to have nose enough for the whole party. My left cheek, also, was puffed out like a dumpling. I couldn’t help saying to myself, “If this is victory, how about that other fellow?”

“Tom,” said Harry Blake, hesitating.

“Well?”

“Did you see Mr. Grimshaw looking out of the recitation-room window just as we left the yard?”

“No; was he, though?”

“I am sure of it.”

“Then he must have seen all the row.”

“Shouldn’t wonder.”

“No, he didn’t,” broke in Adams, “or he would have stopped it short metre; but I guess he saw you pitching into the pump,—which you did uncommonly strong,—and of course he smelt mischief directly.”

“Well, it can’t be helped now,” I reflected.

“—As the monkey said when he fell out of the cocoanut-tree,” added Charley Marden, trying to make me laugh.

It was early candle-light when we reached the house. Miss Abigail, opening the front door, started back at my hilarious appearance. I tried to smile upon her sweetly, but the smile, rippling over my swollen cheek, and dying away like a spent wave on my nose, produced an expression of which Miss Abigail declared she had never seen the like excepting on the face of a Chinese idol.

She hustled me unceremoniously into the presence of my grandfather in the sitting-room. Captain Nutter, as the recognized professional warrior of our family, could not consistently take me to task for fighting Conway; nor was he disposed to do so; for the Captain was well aware of the long-continued provocation I had endured.

“Ah, you rascal!” cried the old gentleman, after hearing my story, “just like me when I was young,—always in one kind of trouble or another. I believe it runs in the family.”

“I think,” said Miss Abigail, without the faintest expression on her countenance, “that a table-spoonful of hot-dro—”

The Captain interrupted Miss Abigail peremptorily, directing her to make a shade out of card-board and black silk, to tie over my eye. Miss Abigail must have been possessed with the idea that I had taken up pugilism as a profession, for she turned out no fewer than six of these blinders.

“They’ll be handy to have in the house,” says Miss Abigail, grimly.

Of course, so great a breach of discipline was not to be passed over by Mr. Grimshaw. He had, as we suspected, witnessed the closing scene of the fight from the school-room window, and the next morning, after prayers, I was not wholly unprepared when Master Conway and myself were called up to the desk for examination. Conway, with a piece of court-plaster in the shape of a Maltese cross on his right cheek, and I with the silk patch over my left eye, caused a general titter through the room.

“Silence!” said Mr. Grimshaw, sharply.

As the reader is already familiar with the leading points in the case of Bailey versus Conway, I shall not report the trial further than to say that Adams, Marden, and several other pupils testified to the fact that Conway had imposed on me ever since my first day at the Temple School. Their evidence also went to show that Conway was a quarrelsome character generally. Bad for Conway. Seth Rodgers, on the part of his friend, proved that I had struck the first blow. That was bad for me.

“If you please, sir,” said Binny Wallace, holding up his hand for permission to speak, “Bailey didn’t fight on his own account; he fought on my account, and, if you please, sir, I am the boy to be blamed, for I was the cause of the trouble.”

This drew out the story of Conway’s harsh treatment of the smaller boys. As Binny related the wrongs of his playfellows, saying very little of his own grievances, I noticed that Mr. Grimshaw’s hand, unknown to himself perhaps, rested lightly from time to time on Wallace’s sunny hair. The examination finished, Mr. Grimshaw leaned on the desk thoughtfully for a moment, and then said:—

“Every boy in this school knows that it is against the rules to fight. If one boy maltreats another, within school-bounds, or within school-hours, that is a matter for me to settle. The case should be laid before me. I disapprove of tale-bearing, I never encourage it in the slightest degree; but when one pupil systematically persecutes a schoolmate, it is the duty of some head-boy to inform me. No pupil has a right to take the law into his own hands. If there is any fighting to be done, I am the proper person to do it. I disapprove of boys’ fighting; it is unnecessary and unchristian. In the present instance, I consider every large boy in this school at fault; but as the offence is one of omission, rather than commission, my punishment must rest only on the two boys convicted of misdemeanor. Conway loses his recess for a month, and Bailey has a page added to his Latin lessons for the next four recitations. I now request Bailey and Conway to shake hands in the presence of the school, and acknowledge their regret at what has occurred.”

Conway and I approached each other slowly and cautiously, as if we were bent upon another hostile collision. We clasped hands in the tamest manner imaginable, and Conway mumbled, “I’m sorry I fought with you.”

“I think you are,” I replied, dryly, “and I’m sorry I had to thrash you.”

“You can go to your seats,” said Mr. Grimshaw, turning his face aside to hide a smile. I am sure my apology was a very good one.

I never had any more trouble with Conway. He and his shadow, Seth Rodgers, gave me a wide berth for many months. Nor was Binny Wallace subjected to further molestation. Miss Abigail’s sanitary stores, including a bottle of opodeldoc, were never called into requisition. The six black silk patches, with their elastic strings, are still dangling from a beam in the garret of the Nutter House, waiting for me to get into fresh difficulties.

T. B. Aldrich.

|

“Tom Brown’s School Days at Rugby.” |

Georgianna’s Letter to William Henry.

My dear brother Billy,—

Kitty isn’t drowned. I’ve got ever so many new dolls. My grandmother went to town, not the same day my kitty did that, but the next day, and she brought me home a new doll, and that same day she went there my father went to Boston, and he brought me home a very big one,—no, not very, but quite big,—and Aunt Phebe went a visiting to somebody’s house that very day and she brought me home a doll, and while she was gone away Hannah Jane dressed over one of Matilda’s old ones new, and none of the folks knew that the others were going to give me a doll, and then Uncle J. said that if it was the family custom to give Georgianna a doll, he would give Georgianna a doll, and he went to the field and catched the colt, and tackled him up into the riding wagon on purpose, and then he started off to town, and when he rode up to our back door there was a great dolly, the biggest one I had, and she was sitting down on the seat, just like a live one. And she had a waterfall, and she had things to take off and put on. Then Uncle J. asked me what I should do with my old dollies that were ’most worn out. And I said I didn’t know what I should. And then Uncle J. said that he would take the lot, for twenty-five cents a head, to put up in his strawberry-bed, for scarecrows, and he asked me if I would sell, and I said I would. And he put the little ones on little poles and the big ones on tall poles, with their arms stretched out, and the one with a long veil looked the funniest, and so did the one dressed up like a sailor boy, but one arm was broke off of him, and a good many of their noses were too. The one that had on old woman’s clothes Uncle J. put a pipe in her mouth. And the one that had a pink gauze dress, but ’tis all faded out now, and a long train, but the train was torn very much, that one has got a great bunch of flowers—paper—pinned on to her, and another in her hand, and the puppy he barks at ’em like everything. My pullet lays, little ones, you know. I hope she won’t do like Lucy Maria’s Leghorn hen. That one flies into the bedroom window every morning, and lays eggs on the bedroom bed. For maybe ’twould come in before I got up. My class has begun to learn geography, and my father has bought me a new geography. But I guess I sha’n’t like to learn it very much if the backside is hard as the foreside is. Uncle J. says no need to worry your mind any about that old fowl, for he’s so tough he couldn’t be killed. I wish you would tell me how long he could live if it wasn’t killed at all, for Uncle J. says they grow tougher every year, and if you let one live too long, he can’t die. But I guess he’s funning, do you? Our hens scratched and scratched up some of my flowers, and so did the rain wash some up that night it came down so hard, but one pretty one bloomed out this morning, but it has budded back again now. Aunt Phebe says she sends her love to you, tied up with this pretty piece of blue ribbon. She says, if you want to, you can take the ribbon and wear it for a neck bow. Grandmother says how do you know but that sailor that went to your school in Old Wonder Boy’s uncle’s vessel is that big boy, that bad one that ran away, you called Tom Cush?

Father laughs to hear about Old Wonder Boy, and he says a bragger ought to be laughed at, and bragging is a bad thing. But he don’t want you to pick out all the bad things about a boy to send home in your letters; says next time you must send home a good thing about him, because he thinks every boy you see has some good things as well as some bad things.

A dear little baby has moved in the house next to our house. It lets me hold her, and its mother lets me drag her out. It’s got little bits of toes, and it’s got a little bit of a nose, and it says “Da da! da da! da da!” And when I was dragging her out, the wheel went over a poor little butterfly, but I guess it was dead before. O, its wings were just as soft! and ’twas a yellow one. And I buried it up in the ground close to where I buried up my little birdie, side of the spring.

Your affectionate sister,

Georgianna.

A Letter from Tom Cush to Dorry.

Dear Friend,—

I have not seen you for a great while. I hope you are in good health. Does William Henry go to school there now? And does Benjie go, and little Bubby Short? I hope they are in good health. Do the Two Betseys keep shop there now? Is Gapper Skyblue alive now? I am in very good health. I go to sea now. That’s where I went when I went away from school. I suppose all the boys hate me, don’t they? But I don’t blame them any for hating me. I should think they would all of them hate me. For I didn’t act very well when I went to that school. Our captain knows about that school, for he is uncle to a boy that has begun to go. He’s sent a letter to him. I wish that boy would write a letter to him, because he might tell about the ones I know.

I’ve been making up my mind about telling you something. I’ve been thinking about it, and thinking about it. I don’t like to tell things very well. But I am going to tell this to you. It isn’t anything to tell. I mean it isn’t like news, or anything happening to anybody. But it is something about when I was sick. For I had a fit of sickness. I don’t mean afterwards, when I was so very sick, but at the first beginning of it.

The captain he took some books out of his chest and said I might have them to read if I wanted to. And I read about a man in one of them, and the king wanted him to do something that the man thought wasn’t right to do; but the man said he would not do what was wrong. And for that he was sent to row in a very large boat among all kinds of bad men, thieves and murderers and the worst kind. They had to row every minute, and were chained to their oars, and above their waists they had no clothes on. They had overseers with long whips. The officers stayed on deck over the rowers’ heads, and when they wanted the vessel to go faster, the overseers made their long whip-lashes cut into the men’s backs till they were all raw and bleeding. Nights the chains were not taken off, and they slept all piled up on each other. Sometimes when the officers were in a hurry, or when there were soldiers aboard, going to fight the enemy’s vessels, then the men wouldn’t have even a minute to eat, and were almost starved to death, and got so weak they would fall over, but then they were whipped again. And when they got to the enemy’s ships, they had to sit and have cannons fired in among them. Then the dead ones were picked up and thrown into the water. And the king told the man that if he wanted to be free, and have plenty to eat and a nice house, and good clothes to wear, all he had to do was to promise to do that wrong thing. But the man said no. For to be chained there would only hurt his body. But to do wrong would hurt his soul.

And I read about some people that lived many hundred years ago and the emperor of that country wanted these people to say that their religion was wrong and his religion was the right one. But they said, “No. We believe ours is true, and we cannot lie.” Then the emperor took away all their property, and pierced them with red-hot irons, and threw some into a place where they kept wild beasts. But they still kept saying, “We cannot lie, we must speak what we believe.” And one was a boy only fifteen years old. And the emperor thought he was so young they could scare him very easy. And he said to him, “Now say you believe the way I want you to, or I will have you shut up in a dark dungeon.” But the boy said, “I will not say what is false.” And he was shut up in a dark dungeon, underground. And one day the emperor said to him, “Say you believe the way I want you to, or I will have you stretched upon a rack.” But the boy said, “I will not speak falsely.” And he was stretched upon a rack till his bones were almost pulled apart. Then the emperor asked, “Now will you believe that my religion is right?” But the boy could not say so. And the emperor said, “Then you’ll be burned alive!” The boy said, “I can suffer the burning, but I cannot lie.” Then he was brought out and the wood was piled up round him, and set on fire, and the boy was burned up with the wood. And while he was burning up, he thanked God for having strength enough to suffer and not lie.

Dorry, I want to tell you how much I’ve been thinking about that man and that boy ever since. And I want to ask you to do something. I’ve been thinking about how mean I was, and what I did there so as not to get punished. And I want you to go see my mother and tell her that I’m ashamed. Don’t make any promises to my mother, but only just tell her, “Tom’s ashamed.” That’s all. I don’t want to make promises. But I know myself just what I mean to do. But I sha’n’t talk about that any.

Give my regards to all inquiring friends.

Your affectionate friend,

Tom.

P. S. Can’t you tell things about me to William Henry, and the others, for it is very hard to me to write a letter? Write soon.

T.

William Henry’s Letter to his Grandmother.

My dear Grandmother,—

I suppose my father has got home again by this time. I like to have my father come to see me. The boys all say my father is a tip-top one. I guess they like to have a man treat them with so many peanuts and good seedcakes. I got back here to-day from Dorry’s cousin’s party. My father let me go. I wish my sister could have seen that party. Tell her when I get there I will tell her all about the little girls, and tell her how cunning the little ones, as small as she, looked dancing, and about the good things we had. O, I never saw such good things before! I didn’t know there were such kinds of good things in the world.

Did my father tell you all about that letter that Tom Cush wrote to Dorry? Ask him to. Dorry sent that letter right to Tom Cush’s mother. And when Dorry and I were walking along together the next morning after the party, she was sitting at her window, and as soon as she saw us she said, “Won’t you come in, boys? Do come in!” And looked so glad! And laughed, and about half cried, after we went in, and it was that same room where we went before. But it didn’t seem so lonesome now, not half. It looked about as sunshiny as our kitchen does, and they had flower-vases. I wish I could get some of those pretty seeds for my sister, for she hasn’t got any of that kind of flowers.

She seemed just as glad to see us! And shook hands and looked so smiling, and so did Tom’s father when he came into the room. He had a belt in his hand that Tom used to wear when he used to belong to that Base-ball Club. And when we saw that, Dorry said, “Why! has Tom got back?” Tom’s mother said, “O no.” But his father said, “O yes! Tom’s got back. He hasn’t got back to our house, but he’s got back. He hasn’t got back to town, but he’s got back. He hasn’t got back to his own country, but he’s got back. For I call that getting back,” says he, “when a boy gets back to the right way of feeling.”

Then Tom’s mother took that belt and hung it up where it used to be before, for it had been taken down and put away, because they didn’t want to have it make them think of Tom so much.

She said when Tom got back in earnest, back to the house, that we two, Dorry and I, must come there and make a visit, and I hope we shall, for they’ve got a pond at the bottom of their garden, and Tom’s father owns a boat, and you mustn’t think I should tip over, for I sha’n’t, and no matter if I should, I can swim to shore easy.

Your affectionate grandchild,

William Henry.

P. S. Bubby Short didn’t mean to, but he sat down on my speckled straw hat, and we couldn’t get it out even again, and I didn’t want him to, but he would go to buy me a new one, and I went with him, but the man didn’t have any, for he said the man that made speckled straw hats was dead and his shop was burnt down, and we found a brown straw hat, but I wouldn’t let Bubby Short pay any of his money, only eight cents, because I didn’t have quite enough. Don’t shopkeepers have the most money of all kinds of men? Wouldn’t you be a shopkeeper when I grow up? It seems just as easy! If you was me would you swap off your white-handled jack-knife your father bought you for a four-blader? My sister said to send some of W. B.’s good things. He wrote a very good composition about heads, the teacher said, and I am going to send it, for that will be sending one of his good things. It’s got in it about two dozen kinds of heads besides our own heads. W. B. is willing for me to copy it off. And Bubby Short wrote a very cunning little one, and if you want to, you may read it. The teacher told us a good deal about heads.

W. H.

W. B.’s Composition.

Heads.

Heads are of different shapes and different sizes. They are full of notions. Large heads do not always hold the most. Some persons can tell just what a man is by the shape of his head. High heads are the best kind. Very knowing people are called long-headed. A fellow that won’t stop for anything or anybody is called hot-headed. If he isn’t quite so bright, they call him soft-headed; if he won’t be coaxed nor turned, they call him pig-headed. Animals have very small heads. The heads of fools slant back. When your head is cut off you are beheaded. Our heads are all covered with hair, except baldheads. There are other kinds of heads besides our heads.

First, there are Barrel-heads. Second, there are Pin-heads. Third, Heads of sermons,—sometimes a minister used to have fifteen heads to one sermon. Fourth, Headwind. Fifth, Head of cattle,—when a farmer reckons up his cows and oxen he calls them so many head of cattle. Sixth, Drumheads,—drumheads are made of sheepskin. Seventh, Heads or tails,—when you toss up pennies. Eighth, Doubleheaders,—when you let off rockets. Ninth, Come to a head—like a boil or a rebellion. Tenth, Cabbageheads,—dunces are called cabbageheads, and good enough for them. Eleventh, At Loggerheads,—when you don’t agree. Twelfth, Heads of chapters. Thirteenth, Head him off,—when you want to stop a horse, or a boy. Fourteenth, Head of the family. Fifteenth, A Blunderhead. Sixteenth, The Masthead,—where they send sailors to punish them. Seventeenth, get up to the head,—when you spell the word right. Eighteenth, The Head of a stream,—where it begins. Nineteenth, Down by the head,—when a vessel is deep loaded at the bows. Twentieth, a Figurehead carved on a vessel. Twenty-first, The Cathead, and that’s the end of a stick of timber that a ship’s anchor hangs by. Twenty-second, A Headland, or cape. Twenty-third, A Head of tobacco. Twenty-fourth, A Bulkhead, which is a partition in a ship. Twenty-fifth, Go ahead,—but first be sure you are right.

Bubby Short’s Composition.

On Morning.

It is very pleasant to get up in the morning and walk in the green fields, and hear the birds sing. The morning is the earliest part of the day. The sun rises in the morning. It is very good for our health to get up early. It is very pleasant to see the sun rise in the morning. In the morning the flowers bloom out and smell very good. If it thunders in the morning, or there’s a rainbow, ’twill be rainy weather. Fish bite best in the morning, when you go a fishing. I like to sleep in the morning.

Mrs. A. M. Diaz.

The lilies were fair, by the garden-wall;

They blossomed for beauty;—and was that all?

Etta checked her steps in the path; said she,

“I will carry a few for my friend to see.”

And she only stayed at my door to say,

“Here are lilies that blossomed for you to-day.”

I took the gift with a glad delight,—

So sweet, so perfect, so pure and white.

How modestly drooping their eyelids fell,

Like a bride’s, when she waits for the marriage-bell!

How fair they were, in the chalice tall!

They blossomed for beauty;—and was that all?

Our Annie came in with a tale of woe,

From a wretched home in the lanes below.

Little Mary, the pride of a poor man’s breast,

Had folded her hands in eternal rest.

Her robes were coarse, and the room was bare,

And nothing of beauty or light was there.

Then I took from the vase my lilies dear,

And gave them the dew of a silent tear;

And parting the fingers, pale and thin,

Annie laid the lilies their clasp within.

And the father and mother will think of her so,

Whenever the flowers in the spring-time grow.

The lilies were fair by the garden-wall;

They blossomed for beauty. That was not all;

For the Father his rain and his sunshine gave,

And they opened for Mary to wear in her grave,

And Etta did more of His will than she knew,

When she said “Here are lilies that blossomed for you.”

Mary B. C. Slade.

“What are you thinking, Lawrence?” said the Doctor, as the family were seated one evening round the library fire.

October had come, the nights were growing cold, and a bright glow from the grate gave a warm and cheerful aspect to the room. The Doctor had been reading the evening paper. Mrs. Dean was knitting a white worsted tippet,—so very white and soft, that anybody would have known it was intended for Lawrence’s little cousin Ethel,—for where was there another little throat or chin it would become so well? Ethel was rocking pussy to sleep in her doll’s cradle,—only pussy wasn’t very sleepy, and the sight of the white tippet was a constant temptation to her playful paws.

As for Lawrence, he was gazing abstractedly at the fire,—scarcely moving, except when, every minute or two, he took a lump of coal from the hod, and dropped it carefully into the grate, and never once speaking, for I don’t know how long, until his uncle startled him with his sudden question.

“Oh! I? I was thinking how curious it is. I mean the fire. And the coal that makes the fire,—where it comes from, and how we happen to be burning it here. Ever since we saw the great furnaces at the glass-works, I can’t keep it out of my head.”

“No!” cried little Ethel; “he won’t even look at my kitty,—and she is so interesting in her nightcap and nightgown! Only see how quiet she is! There! rock-a-by, baby, upon the tree-top! When the wind blows, the cradle will—Dear me, kitty!” she exclaimed; for there was just then an exciting movement of the white tippet, and away went kitty, nightcap, nightgown, and all, to have a snatch at it.

There was a good laugh at the funny appearance pussy made, dressed up so, with the nightcap-strings tied under her whiskers, and her paws in sleeves. And Mrs. Dean said, “You see, Ethel, cats will be cats, and boys will be boys. You mustn’t blame them because they won’t do always just as you would like to have them. Lawrence is a good deal more interested in coal, just now, than he is in cats with nightcaps.”

“For a while it was all glass,” said Ethel, putting pussy back into the cradle. “There wasn’t a glass thing in the house that he didn’t talk about, and tell us how it was made.”

“Yes, and didn’t you like to have me?” said Lawrence. “You made me tell you over and over again how your little ruby cup was made.”

“Yes, indeed; for that is very pretty, with my initials engraved on it, and the little flower-wreath around them to match yours. But coal,—ugly black coal!—I don’t see what there is interesting in that!”

“Lawrence does, and I am very glad of it,” said the Doctor. “How would you like to see where the coal comes from,—eh, Lawrence?”

“That’s what I’ve been wishing for!” exclaimed the boy. “If I could only go into a coal mine!”

The good Doctor smiled. “Well, now, I’ll tell you what I have been thinking. Some gentlemen of my acquaintance talk of purchasing coal lands in Pennsylvania; and they have their eye on some near Scranton, in Luzerne County,—which you will find, when you turn to your map, about the centre of the northeastern quarter of the State. They have asked me to go out and look at this property for them, and I think of starting next week. Would you like to go with me?”

Lawrence fairly leaped out of his chair with delight. “Would I? O uncle!”

“There she goes again!” said Ethel, with a rueful face, holding pussy’s nightgown in her hand, having pulled it off in a vain attempt to detain the runaway. “Why couldn’t you keep still, coz, when she was just getting so quiet?”

“Why, I’m going to Pennsylvania!” cried Lawrence,—as if that were excuse enough for the wildest conduct.

“Yes, but you needn’t dance up and down that way, if you are! Now she won’t go to sleep to-night!”

“Neither will Lawrence, I’m afraid,” said his aunt. “He shouldn’t have been told of anything so exciting until morning.”

The Doctor laughed, and said, “I knew he would have to lie awake one night, thinking of it, and that may as well be to-night.”

Lawrence seemed to be of the same opinion. He went to bed as usual; but he didn’t want to sleep. He lay awake, thinking of the promised journey, and of coal mines and miners, for an hour or two. He was so excited, that when he fell asleep at last he dreamed that he was a locomotive in nightcap and nightgown, and that, taking fright at the sound of a gun, he ran off the track, and smashed up a long passenger train. Then it seemed to him that the noise he had taken for a gun was in fact the explosion of his own boiler; then, that he was the engineer, and that he was knocked very high by repeated explosions, which wouldn’t let him come down out of the freezing weather. He awoke, in the midst of his trouble, to find that he had thrown off the bed-clothes, that he was shivering with the cold, and that a window-blind was slamming.

The days seemed very long to the boy, until at last the time came for bidding his aunt and cousin good by, and starting with his uncle on their journey.

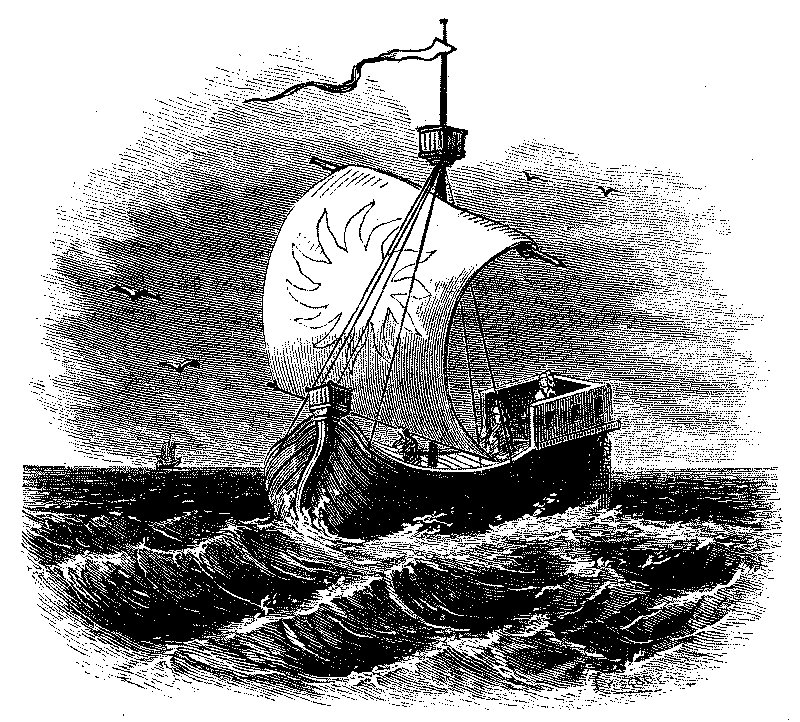

They took the steamboat train for New York; and Lawrence, after sleeping soundly “as a top,” as he said, “on that pantry-shelf,”—meaning the berth in the state-room,—awoke the next morning in the great city.

He had a few hours to look about him, while his uncle transacted some business; then they crossed the river in a ferry-boat, (how keenly the boy enjoyed all that!) and, taking a train on the other side, rattled away, across New Jersey, and far up into Pennsylvania, reaching Scranton the same evening.

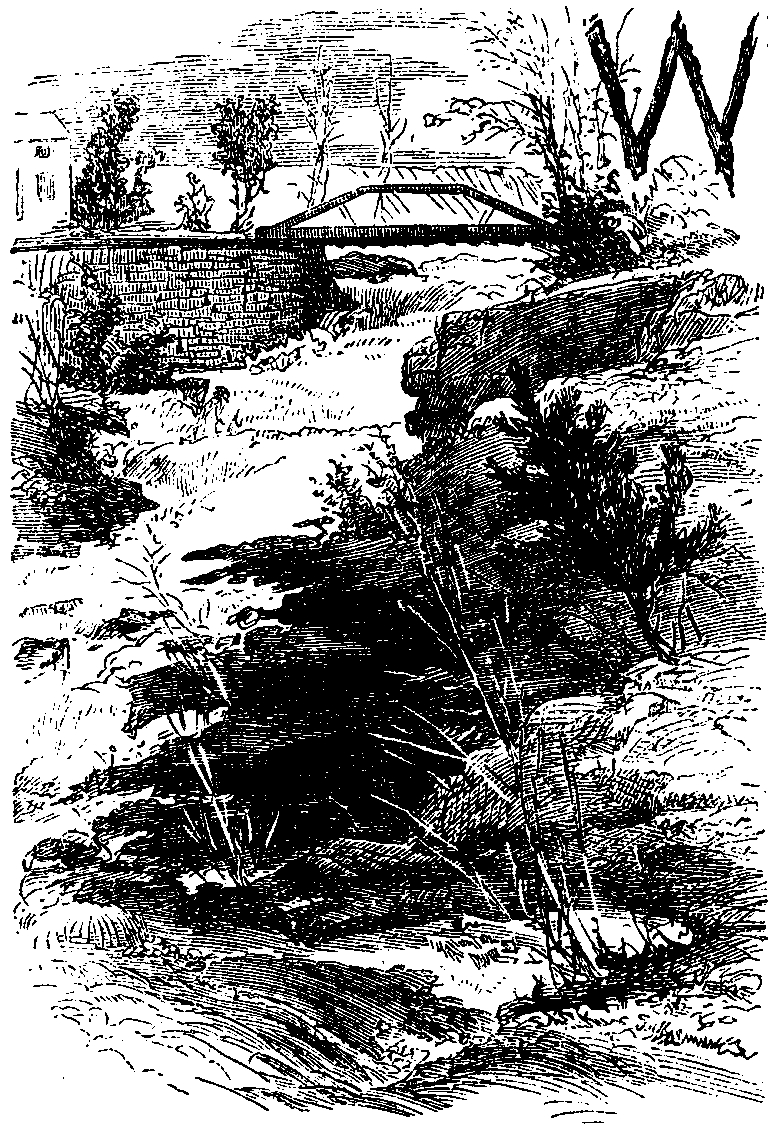

It was, of course, a delightful journey to the boy, and he was almost sorry when it came to an end. Yet the end was the most interesting part of it. The train went winding in among the mountains that enclose the Lackawanna Valley; they were covered with wild forests, still bright with the glorious tints of October, and, through a deep ravine that divided them, a beautiful stream—rightly named “Roaring Brook”—came rushing down. On the other side from this,—that is, on the right,—Little Roaring Brook came leaping from the rocks in white cascades, and, disappearing for a moment under the railroad bridge, fell into the larger stream below. Then Lawrence had exciting glimpses of steaming colliery buildings, with their black mounds—almost mountains—of waste coal and slate from the mines, pushing out into the narrow valley. Then the train passed within sight of immense iron mills and blast furnaces, flashing and flaming in the early twilight; then it came to a stop; and an omnibus whirled them away to a hotel in the city.

It was too late to see much of Scranton that night; but Lawrence consoled himself with anticipations of pleasure in going about with his uncle the next morning. He was, however, destined to be disappointed.

A tall gentleman, in gray overcoat and gray whiskers, whom he left talking with his uncle in the reading-room, was still at the hotel the next morning. After breakfast, a buggy came to the door of the hotel,—for himself and his uncle, Lawrence supposed; but no, it was for the tall gentleman; and the Doctor was going to ride with him.

“I’ve an engagement with this man,” said the Doctor, taking his nephew aside; “and I see his buggy has seats for only two. But you won’t mind being left alone for a few hours.”

“O, certainly not,” said Lawrence, with as cheerful a face as he could assume, though with a swelling heart. And his uncle rode away.

He watched the buggy as it disappeared up the long street; then a strange feeling of desolation came over him. The town was full of things worth seeing, but how could he, an utter stranger, hope to find them out? If he could only have gone in the buggy!

It was not his way, however, to spend much time in lamenting things that could not be helped. The morning was fine. The sunlight was beautiful on the mountains. “There’s no use feeling bad,” thought he. “I’m lucky to be here, any way. I can see the river and the city, if nothing else.”

So he went out, in good spirits, and spent the forenoon very happily. Yet he wasn’t quite satisfied with himself when he returned to the hotel at dinner-time. He had seen and enjoyed many things, but not what he most wished to see,—the interior of a coal mine. He had stood in silent wonder before more than one great colliery building, and heard the thundering crash of the coal dumped into the breakers; he had even looked into one, and seen the loaded cars from the deep mines whirled up swiftly, by the powerful engines, out of the black pit, and whirled back again empty, with terrible rapidity, and he had asked himself if he would ever have the courage to go down in one of them. He thought he would, if any one familiar with the mines would go with him; but everybody he saw appeared too busy to give a lad like him the least attention. “I must make acquaintances,” thought he; and he determined to begin at the dinner-table,—his uncle not having returned.

At dinner, however, he was quite disheartened by what he saw. Sixteen young men sat at the same table with himself, and scarcely sixteen words were spoken by all of them during the solemn ceremony of eating. They were all good-looking, and had clean dickies, and white foreheads, and appeared so intelligent, and so much at their ease, that their unsocial behavior quite astonished him. Indeed, it overcame him so, that he would no more have ventured to break the awful silence by speaking loud than if he had been sitting in his uncle’s church-pew during sermon-time.

While he was wondering what they could all be thinking about, another young man entered,—a very young man, I may say, for his age could scarcely have exceeded that of Lawrence himself, although his surprisingly cool and self-possessed manners made him appear much older. He had a pleasant face, a jaunty short jacket, and large side-pockets. In these he carried his hands, and, in one of them, the end of a cane, which stuck up behind him at about the angle of a plough-handle. He looked around with a knowing expression, and finally, seeming, after mature thought on the subject, to have selected Lawrence as a table-companion, went and sat down opposite him.

“Here, Muff!” said he; and Lawrence noticed that he was followed by a very small dog, in a very large fleece of white curls, that made him look as if Nature had at first designed him for a dog, but had afterwards changed her mind, and finished him up as a sheep.

The young man took the cane from his pocket, held it up directly over the animal’s upturned nose, and dropped it. Click!—the animal’s jaws flew open like a trap, and caught it.

“Turn three times!” said the young man.

The animal immediately got up on his hind legs, with his head thrown back, balancing the stick, and began to revolve, like a capstan with a lever thrust through it.

“Go!” said the young man; and the dog, dropping down on all fours, still holding the cane, retired with it to the door of the dining-room, where he laid it down under the hat-table, and put his paws on it, and kept vigilant guard over it, against all comers. The tall head-waiter made one or two attempts to turn him out, but got growled and snapped at so smartly that he finally let him remain.

Everybody appeared to be amused by this trifling incident, especially some children at a table near by, who could not laugh enough to see the tall waiter retreat from such a tangled little ball of wool. Even the solemn young men relaxed their grave countenances, and from that moment became sociable.

Meanwhile, the dog’s youthful master, not appearing in the least aware that either he or his pet had done anything extraordinary, glanced over the bill of fare, with the air of a person making judicious selections. Then he gave his order, calling the young lady who waited on him “Sis,” and talking to her very much as if he had been an old friend of her father’s, and held her on his knee when she was little. Then, resting his arms on the table, he looked across it at Lawrence, and gave a short nod.

Lawrence gave a short nod in return.

“Fine day,” said the young fellow.

“Beautiful,” replied Lawrence, adding, “That’s a splendid pup of yours,”—though he knew that splendid wasn’t just the word.

“He’ll do,” said the young fellow, with a glance at the door. “ ‘No dogs allowed in the dining-hall,’ says the chap in the white apron, as I came in. ‘Is that the rule of this hotel?’ says I. ‘Yes, sir,’ says he. ‘And a very good rule it is,’ says I; ‘but it don’t say anything about sheep’; and, while we were talking, Muff and I walked in. I’d like to see the place where Muff and I can’t go!—Thank you, sis,” to the young lady bringing his dinner.—“Acquainted in Scranton?”

Lawrence said no,—he arrived in town only the evening before with his uncle.

“Indeed! I came with my uncle, Mr. Fitz Adam, the celebrated mining engineer. You’ve heard of him, of course?”

Lawrence was forced to own that he had not heard of the celebrated Mr. Fitz Adam. Thereupon the young fellow laid down his knife and fork, and looked at him over his plate with mild astonishment, making Lawrence painfully aware how much he had lowered himself in his (the young fellow’s) esteem by that confession.

“May I ask where you came from, sir?” he said,—as if that must be a curious country, indeed, where the inhabitants had never heard of his uncle.

Lawrence hardly knew at first what to make of this impertinence, but wisely concluded to make a joke of it.

“I am from Massachusetts,” said he, with a droll smile just puckering the corners of his mouth. “And my uncle is the distinguished Doctor Dean. You have heard of him, of course?”

The young fellow laughed, and nodded at Lawrence approvingly; and Lawrence felt that this reply had raised him again in the young gentleman’s esteem. “We are even on that.—Butter, if you please, sis. Thank you, sis. And see here, sis!—can’t you get me a piping-hot sweet potato? I’ll remember you in my will, if you’ll be so kind as to oblige me.” Then, turning again to Lawrence: “We’re bound to speak well of our uncles, I see, though mine served me a remarkably shabby trick this morning.”

“How so?”

“He left me asleep in my bed, and, as near as I can find out, went off to ride with another gentleman.”

“Exactly what my uncle did by me!” said Lawrence, “only I wasn’t asleep in bed. Is your uncle a tall man in gray overcoat and gray whiskers?”

“The very same! You don’t say he and your uncle—well! this is a coincidence! Your hand on it!” And the young fellow stretched his arm across the table. “My name,” said he, “is Mr. Clarence Fitz Adam.”

“Mine is Lawrence Livingstone.” And from that moment they were friends.

“I wish you had been with me this morning,” said Mr. Clarence, wiping his elbow,—for he had dipped it into the gravy when he shook hands. “I have seen Scranton outside, inside, and”—he pointed downward, mysteriously—“underside.”

“Not in the coal mines?” said Lawrence, with a pang of envy. “I wanted to go down in a shaft, but didn’t know how the thing was to be done.”

“You ain’t bashful, I hope? You’ll find bashfulness don’t pay, if you are going through the world,” said Mr. Clarence, with an air of old experience. “The world’s a big shop. ‘No admittance,’ says the chap at the door. ‘O, excuse me!’ you say, and back out. But what do I say? ‘No admittance? Certainly, that’s all right,—an excellent regulation; but, if you please, sir,’—then I go on and ask questions, and the first thing he knows, he is showing me round. Come, I’ll get my pup fed, then we’ll take a stroll together.”

Lawrence was well pleased, for he was certain Mr. Clarence must be a capital fellow to go about with.

They walked down the street arm in arm, and crossed the river on the railroad bridge.

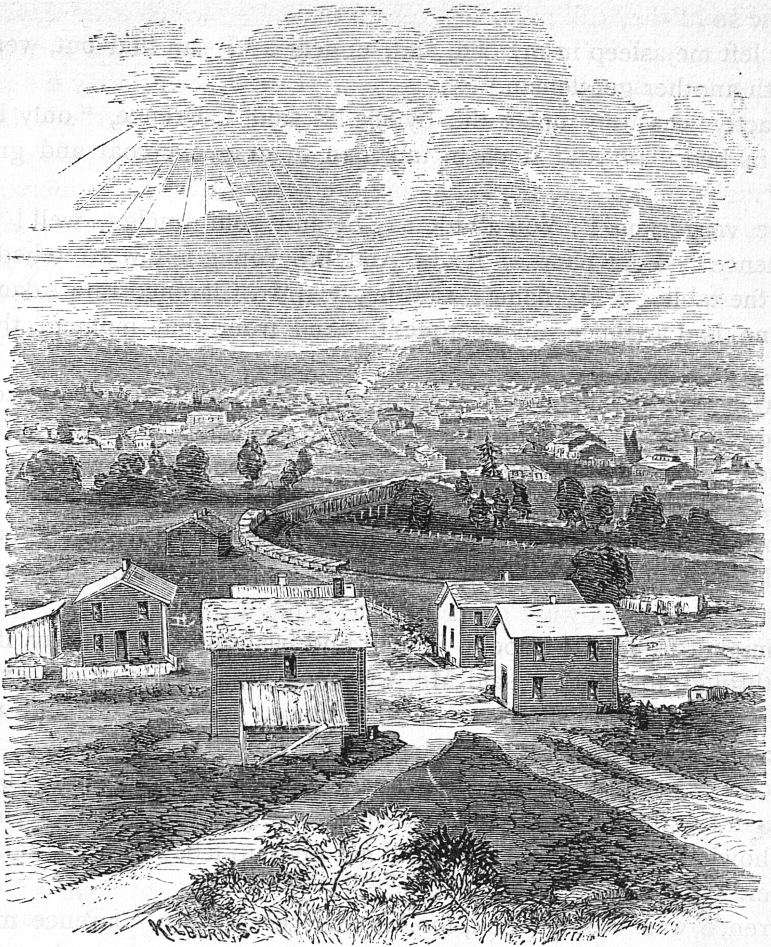

“This is the famous Lackawanna, as I suppose you have learned,” said Mr. Clarence, pointing downwards at the hurrying water. “It is the stream that gives its name to all this coal region about Scranton. This side of the river,” he continued, when they had crossed, “is Hyde Park. It is the fifth ward of the city. Let’s climb the bank above the railroad, and get a view. These,” said he, turning, when they had reached a favorable point,—“these plain-looking little houses right before us here are miners’ houses.”

“I don’t see but that they look very much like the houses of any other class of laborers,” said Lawrence; “and I had imagined, somehow, they must be different,—little, low, black, dismal, mysterious huts, to correspond with the miners’ dismal occupation, you know.”

“They may be so in some countries. But in this favored land of liberty,” said Mr. Clarence, smiling at his own eloquence, “the miners are so well paid, that they can afford to live very comfortably, as you see.”

“Well,” he went on, pointing with his cane, “there are the banks of the Lackawanna, and the railroad bridge we came over. We are here on the west bank; and there is the main part of the city on the east or left bank. This is all Scranton,—a fine, large city, as you see. But it has all been built up within a few years. A few years ago, this country was all a wilderness. Do you know what has made the difference? Coal, anthracite coal,” Mr. Clarence continued, answering his own question. “Coal built those fine brick blocks, those churches, hotels, stores. Coal built those big blast furnaces and iron mills. Coal built the railroads you and I came in on yesterday. Coal has done all this, and more,”—adding, by way of climax, “it has brought me the pleasure of your acquaintance.”

“This is a funny-looking brick church, up on the hill behind us,” said Lawrence, “with the end cracked open, and the sides held up with props.”

“Yes. And just beyond it you’ll see a house tipped up on one end, great pits in the earth, and other irregularities. Can you guess how they came about? Coal is to blame here too. There are mines all under where we stand. They extend like so many streets beneath the streets of the town,—two or three hundred feet below, of course. In place of houses and blocks down there, as you’ll see, for we are going into a mine presently, they have what they call pillars,—pillars of coal,—which they leave to support the country above, when they are undermining it. That is a very important consideration, where a city stands. But it seems they didn’t leave quite support enough under this part; for one day the ground began to shake and tremble; and it shook and trembled, every little while, all that day and night, and all the next day, and the great pillars down there groaned and complained; and now and then the coal would fly off from them, as if it was angry, and the props—for they put wooden props under the roof, besides—broke like pipe-stems; and finally, the next night, the crash came. The pillars had finally given way, and the country had settled. It looks now as if a young earthquake had kicked it.”

“Who pays the damages under such circumstances?”

“I believe that question hasn’t been decided yet. The owner of the land sells house-lots, reserving the right to mine the coal under them. He sells the right to the coal companies. Coal companies take out too much coal,—crash,—down go the house-lots, with the houses on them. Who is to blame? You see, it is a delicate legal point,” added Mr. Clarence, in his fine way. “And now, what do you say to going down and taking a look at that underground country?”

“I should be delighted to!” said Lawrence.

“Well, come along. I’ve been here before, you see. Come, Muff!” And Mr. Clarence led the way, swinging his cane.

J. T. Trowbridge.

“Heu—eu!” said the wind. “Here I am again!” And he gave little Carl Richter’s window a shake so that the panes rattled till they almost fell in pieces, and then he flew off,—like the wild fellow he was.

Carl started up in bed and opened his eyes wide. “That’s the old north-east!” said he, and began to listen. It was dark, as if it were the middle of the night, and Carl could not see anything in the room; only a patch of gray in the blackness showed where the window was. But he could hear a curious noise, or rather a good many different noises, that made him open his eyes wider than ever, only there was nobody there to see how big and round they got to be. First, there was the wind, that seemed trying to get in at all the doors and windows of the house, blowing and whistling, as if it were so cold,—so cold,—and wanted to get into Carl’s own warm little bed and be tucked up snug. Then there were the pine-trees sobbing and sighing to themselves, and Carl knew that far up the mountain, and for miles and miles away, all the pines were moaning and bending, just like those at his father’s door. Then—and it was to this that Carl was listening so eagerly—there was a sort of muffled roar, that grew louder and louder, and suddenly a report almost like that of a cannon, and after that a horrid, choking sound, as if some terribly big creature were trying to draw a deep breath, and then the roar again. I know more than one little boy, no younger than Carl was, who would have scampered under the bed-clothes, and perhaps called for his mother to come, on hearing that dreadful noise. I know one little boy who would have thought that a bear was in the room, or under the bed, and I am pretty sure that he would have screamed, and that his mother would have had to sit by him and hold his hand till he fell asleep again. But Carl did none of these things, and wasn’t in the least frightened. He had heard the same noise often enough before, and knew perfectly well what it meant. “That’s the old Northeast!” said he again, “and blustering more than ever.” But he did not say it in English as I have written it down, for Carl was a little German boy, and used to troll out the funniest long sentences, that would sound to your ears as if he were saying nothing but ugh! ugh! ugh! And to hear little Sophie, who was only three years old, try to sputter out some ugly word,—that would have made you laugh indeed. Carl knew enough of English to talk to the people who came to see his father, for they lived in America, where it is not everybody who can understand German. That seemed very strange to Carl. But always at home Carl spoke in German,—to his father and mother, and to Sophie and Johann, and to the cow and the robins, and to the dear old dog, whom he always called “Thou,” and whom he loved better than anything else that he had in the world.

Carl had come to America when he was a very little baby,—far too little to know anything of the land where he was born, or even the passage in the great ship; so his only associations were with the rocky nook where he now lived, and the little house around which the wind whistled that wild autumn morning. It was on the coast, with a great bare mountain rising up behind it, and the merry sea in front,—the sea over which Carl had been carried, a little, unconscious baby, in his mother’s arms. Often and often when he had been listening to his mother’s stories of the country where he was born, and which she loved so well, Carl would go out and sit on the rocks and rest his little brown cheek on his hand, and look across the silver sea as it flashed and danced in the sunlight. “When I am a man, I will go back to the fatherland,” he would say to himself. But he loved the new home too; there was the mountain to climb, and the rocks to play among, and his mother had planted a little patch of German daisies in the garden, that bloomed and smelled as sweet as they ever could have done anywhere. Then there were the beach and the sea, and Carl already owned a little boat, which he could row all alone; he could even take Johann with him sometimes, when the sea was quiet, and the little boy would promise to sit still. Carl had never been to school, for the nearest house was two miles off; but his mother had taught him to read and to write, and he could swim, and row, and drive the horse, and milk the cow, and he was learning to sail a boat,—yes, and sometimes he could tell when a storm was coming. He was the oldest of the children; then there were Johann, and Sophie, and the new baby, who was so very little that he hadn’t any name at all. They were all great sturdy children, with blue eyes and yellow hair, and fair, merry faces; only Carl was not fair, but as brown as a little Indian, with the sun and wind. And now you know what it was that Carl heard as he sat up in bed and listened. It was the sound of the waves that were beating on the rocks of Spouting Point.

Carl put his hand cautiously over to the side of the bed where Johann was, to see if he was awake. But Johann was certainly sound asleep; he had been playing hard all the day before, and slept as quietly as if the gentlest summer breeze were blowing. Then Carl got out of bed softly, so as not to wake him, and pattered along with his little bare feet to the window. It was still dark, but the east was beginning to grow gray, and down on the point he could see a white line of foam shooting up and fading away in the darkness again. He stayed there, kneeling down at the window, watching the white gleam that was a hundred times finer than any fountain, till he began to feel cold. By this time it was a good deal lighter, and Carl could distinguish the rocks quite plainly. “I will get up and go to see the breakers,” he said; “it is nearly time for the morning-red.” So he dressed himself quietly and quickly, always careful not to disturb Johann, and crept downstairs with his shoes in his hand. When he passed the door of the room where his mother was sleeping, he stopped a moment, and put his hand on the latch. Then he thought, “No, I will not wake her; I shall be back before she wakes,” and was creeping away again. But the mother was waking, and heard; or was it only the mother’s love which never sleeps, and which felt the little footsteps so dear to her? However that may be, Carl heard the mother’s voice calling to him.

“Where art thou going, child?” said she, when he had come into the room, and was standing beside her bed, and she saw that he was dressed in what he called his “weather-clothes.”

“Dost thou not hear the wind, Mütterchen?” said Carl, kissing her. “I am going to the point, to see the wind toss the waves about. That will be fine to-day!”

“Carl, Carl, why canst thou not sleep soundly in thy bed?” said his mother, smiling. “Thou art a true storm-chicken. Do not go among the rocks, lest thou stumble. And do not stay long, or I shall think something has befallen thee.”

“No, only a little,” said Carl. “It is near the daybreak already. How is the little brother?”

“He sleeps,” said his mother, “sweet as a little angel. Do not go near the rocks; remember, Carl.”

“No, Mütterchen,” said Carl, kissing her again, and went out, and softly shut the door. Down stairs before the hearth lay the dog Bezo. He was awake, too, and when Carl put his little round head into the house-room, he rapped on the floor with his tail. That was his way of saying good morning.

“Come, Bezo, and shake the sleep out of thine eyes,” cried Carl. “Dost thou not hear Northeast? How the old fellow rages! Let us come out and mock him, Bezo!”

But Bezo seemed to like the warm room better. He got up and stretched himself and yawned, licked the hand of his little master, and laid himself down again.

“Thou good-for-nothing!” said Carl. “Thou wouldst sit all day long, and roast like a potato among the ashes, if I did not drag thee out. Come!” he cried, and seized one of Bezo’s paws, and pulled him away from the warm hearth. Then he tied his hat on tight, and opened the outer door.

Whew! That was a blast! At the very instant that Carl opened the door, came a furious gust that tipped his hat down over his eyes, and blew Bezo’s hair all the wrong way up his back. But Carl planted his sturdy little legs very far apart on the ground, and the wind didn’t succeed in knocking him over, though it made him stagger and clinch his hands hard. The pine-trees bent and rattled, and louder than ever Carl could hear the slap of the surf, and the roar of the coming waves. He pulled his hat on once more, and called to Bezo to keep up the dog’s spirits, but found he had not much breath to spare. “That’s funny,” said he to himself, “that when there is so much wind, I should have so little breath!” Then he started to run down to the beach as fast as the wind would let him. It blew in his face, and tried to trip him up at every step, and once it nearly stole his hat, but Carl’s little brown fist clutched the brim just in time. Bezo kept along by his side, and so, panting and rosy, Carl stood, at last, just beyond highwater mark on the sand-strip. Down amid the sea-weed at his feet he saw Johann’s little boat, which their mother had rigged so carefully, and which Johann had been playing with the day before. Carl took it up and put it on some rocks where it was safer, and fastened it down so that it might not be blown away. “Poor Johann must not lose his boat till he can have a real one,” said Carl to himself, “like mine.”

Well, it was fine! The waves seemed tumbling over one another in their haste to get to the land, and to swallow up the little boy who stood there so coolly just beyond their reach. But, after all, the breakwater and the pier made it comparatively calm where Carl was; it was out on the rocks that he was looking, and there the spray was tossing and whirling, and great green walls of water rose every moment. Carl enjoyed it. He knew the rough old rocks would hold their own against the angry water, and he clapped his hands and shouted every time a wave bigger than the rest fell and shivered itself into foam against them. But all of a sudden something caught his eye which was not the foam,—something out beyond on the sea. Could he have seen clearly? Carl put his hand on Bezo’s head, and stared; his heart almost stopped beating for a moment. Another wave rose up, hurled itself against the crags, and then Carl saw the ship with its masts all broken, and a fragment of sail showing, come driving straight onwards. It was not a fishing-schooner, such as he saw every day passing, Carl knew at a glance, but a much larger vessel, evidently out of her course and helpless, drifting at the mercy of the merciless wind and sea. Poor little Carl stood looking on in horror for a moment, and clutched Bezo’s hair so tightly that he whined. But Carl didn’t hear him; he was thinking of nothing but the ship, nearer and nearer every moment. He knew that there were men on board who were trying to guide her motions, and he knew, too, what the men on board did not,—of the terrible sunken ledge on which she would strike, unless some quick hand were there to grasp the rudder; unless—Carl thought of the dear land over the sea, and perhaps on board there were some who came from thence,—countrymen, friends. The ledge seemed to Carl’s excited fancy to come to meet the fated ship; he knew so well where the cruel rocks were waiting for their prey.

“I cannot bear it!” cried he. “Come, Bezo!” and he started out on the pier, cautiously yet swiftly. There was his little See-mädchen fast to her moorings, and the oars lashed to a pile. Carl cast one glimpse at the breakers, and listened to that savage roar again, and gulped down something like a great sob. “I have been out in as rough a time with the father,” said he, and knelt down, and began to untie the boat. Bezo stood by him, puzzled and whining. Little Carl’s cheek was pale for all the sunburn, but he only said to himself, “I must show them the ledge,” over and over again, as if to keep down that curious rising in his throat; “there is nobody else.”

Suddenly came a dull sound that was not all the breaking of water, and Carl gave a cry and started to his feet, with one arm round the post to steady himself. It had come so soon. There was the vessel driven upon the ledge, and the breakers pounding, pounding, pounding. And back rang an answering cry to Carl’s,—the cry of men in sudden and utter despair,—and that drove every thought but one out of Carl’s generous, big heart. He stood up as tall as he could, and made a trumpet of his hand, and shouted in English, “See! this boat comes!” forgetting that the wind drove his poor little voice back, and choked it, and utterly silenced it. Then he turned, and gave one last look at the cottage. It was dark and still; behind it a great black mass rose that was the mountain; he knew that in a little while it would be red-capped, for the day was near. “The father must be here soon,” he muttered to himself, “and I have been out in as rough a time.”

Then he knelt down, and said the little prayer that he said every night at his mother’s knee, and then in another moment the See-mädchen was on the top of a wave with every muscle in Carl’s arms in play, and Bezo crouched at his feet. He knew the boat would live in almost any sea, “and I can swim, and so can Bezo,” he thought. Bezo sat watching him, never stirring; his intelligent eyes never moved from Carl’s face. The tide was going out; that helped him. O that the ship might not go to pieces before he could reach her! The little See-mädchen could only hold three,—but Carl never thought of that; he pulled stoutly on. Now a light came in the cottage, at the window of his mother’s room. Carl thought of little Sophie, with her yellow hair, and her eyes like the blue forget-me-nots. And then a mighty wave came, and swept the poor little boat away like a feather. Carl saw the rocks looming,—put out a slender oar to stave off—

When I went to see Carl’s mother last summer, she took me out, crying, to the little grave. It is near the house, and they have planted the sweet German daisies upon it; and when I saw it they were all in bloom, and the tender grass spread its velvet over the mound. And while I stood there, she told me how Bezo had dragged Carl’s poor little body up on the beach, wounded and bleeding himself, but having lived long enough to save his master, he thought, and how, as the first sunlight made the mountain-top red, Carl’s father found them there, both dead.

Johann stood by his mother’s side, and took her hand and kissed it. “Yes, I have thee left, my Johann,” said she, “and we have not lost our Carl forever.”

I stooped and picked one of the daisies which grew so fresh over the dead child, and I thought of the gallant little heart that had nourished the flower I held, and of the young life that was as sweet and fair, and of the love and tenderness of the Heaven that is over us all.

Lily Nelson.

It was the evening of New Year’s Day, and Minnie and Mysie, seated upon a sofa, with a great box of bon-bons, the gift of Signor Magnifico, between them, seriously devoted themselves to its consideration.

“What a pity we cannot devour sweetmeats forever!” remarked Minnie, at last, laying down a charming rose-colored heart with a profound sigh.

Mysie did not answer; in fact, her mouth was too full to admit of speech, and Minnie, after dreamily regarding the bonbonnière for a few moments, continued: “It is all very well to laugh at George the Third for asking how the apple got inside the dumpling, but I should really like to inquire how the drop of cream gets inside a chocolate Duchesse, or the liquid into a wine or brandy drop.”

“I can inform you how it gets out,” replied Mysie, savagely rubbing away at a spot upon her pet blue silk dress, caused by incautiously biting a Duchesse in two instead of putting it into her mouth entire.