* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks. An Illustrated Magazine for Boys and Girls. Volume 5, Issue 4

Date of first publication: 1869

Author: John Townsend Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom (editors)

Date first posted: Dec. 15, 2015

Date last updated: Dec. 15, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20151214

This ebook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

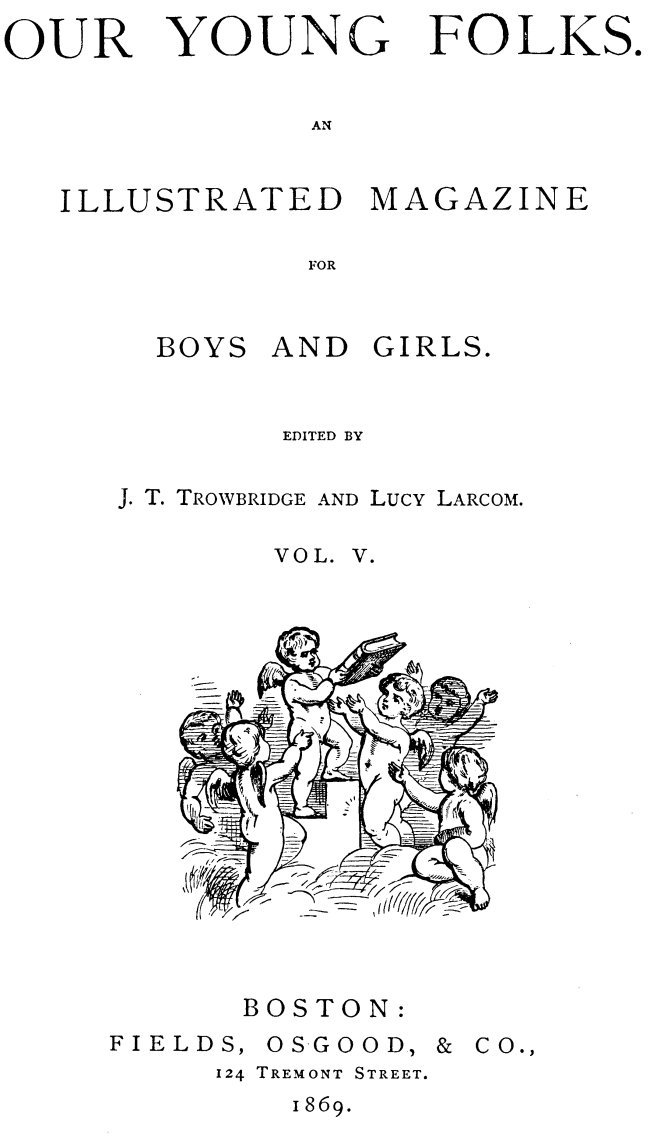

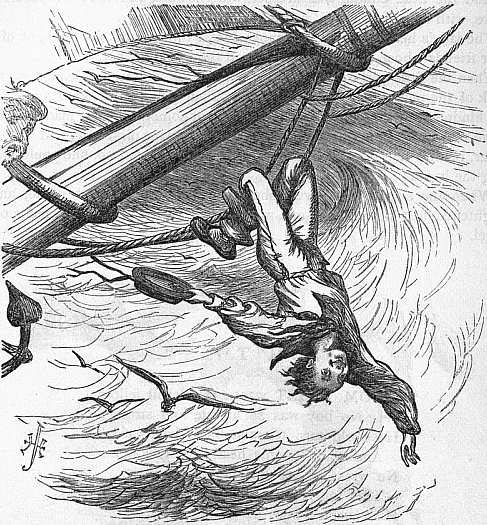

“At this moment a figure was seen leaping wildly from the inside of the blazing coach.”

Drawn by S. Eytinge, Jr.] [See The Story of a Bad Boy, page 209.

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. V. | APRIL, 1869. | No. IV. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by Fields, Osgood, & Co., in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

Two months had elapsed since my arrival at Rivermouth, when the approach of an important celebration produced the greatest excitement among the juvenile population of the town.

There was very little hard study done in the Temple Grammar School the week preceding the Fourth of July. For my part, my heart and brain were so full of fire-crackers, Roman-candles, rockets, pin-wheels, squibs, and gunpowder in various seductive forms, that I wonder I didn’t explode under Mr. Grimshaw’s very nose. I couldn’t do a sum to save me; I couldn’t tell, for love or money, whether Tallahassee was the capital of Tennessee or of Florida; the present and the pluperfect tenses were inextricably mixed in my memory, and I didn’t know a verb from an adjective when I met one. This was not alone my condition, but that of every boy in the school.

Mr. Grimshaw considerately made allowances for our temporary distraction, and sought to fix our interest on the lessons by connecting them directly or indirectly with the coming Event. The class in arithmetic, for instance, was requested to state how many boxes of fire-crackers, each box measuring sixteen inches square, could be stored in a room of such and such dimensions. He gave us the Declaration of Independence for a parsing exercise, and in geography confined his questions almost exclusively to localities rendered famous in the Revolutionary war.

“What did the people of Boston do with the tea on board the English vessels?” asked our wily instructor.

“Threw it into the river!” shrieked the boys, with an impetuosity that made Mr. Grimshaw smile in spite of himself. One luckless urchin said, “Chucked it,” for which happy expression he was kept in at recess.

Notwithstanding these clever stratagems, there was not much solid work done by anybody. The trail of the serpent (an inexpensive but dangerous fire-toy) was over us all. We went round deformed by quantities of Chinese crackers artlessly concealed in our trousers-pockets; and if a boy whipped out his handkerchief without proper precaution, he was sure to let off two or three torpedoes.

Even Mr. Grimshaw was made a sort of accessory to the universal demoralization. In calling the school to order, he always rapped on the table with a heavy ruler. Under the green baize table-cloth, on the exact spot where he usually struck, a certain boy, whose name I withhold, placed a fat torpedo. The result was a loud explosion, which caused Mr. Grimshaw to look queer. Charley Marden was at the water-pail, at the time, and directed general attention to himself by strangling for several seconds and then squirting a slender thread of water over the blackboard.

Mr. Grimshaw fixed his eyes reproachfully on Charley, but said nothing. The real culprit (it wasn’t Charley Marden, but the boy whose name I withhold) instantly regretted his badness, and after school confessed the whole thing to Mr. Grimshaw, who heaped coals of fire upon the nameless boy’s head by giving him five cents for the Fourth of July. If Mr. Grimshaw had caned this unknown youth, the punishment would not have been half so severe.

On the last day of June, the Captain received a letter from my father, enclosing five dollars “for my son Tom,” which enabled that young gentleman to make regal preparations for the celebration of our national independence. A portion of this money, two dollars, I hastened to invest in fireworks; the balance I put by for contingencies. In placing the fund in my possession, the Captain imposed one condition that dampened my ardor considerably,—I was to buy no gunpowder. I might have all the snapping-crackers and torpedoes I wanted; but gunpowder was out of the question.

I thought this rather hard, for all my young friends were provided with pistols of various sizes. Pepper Whitcomb had a horse-pistol nearly as large as himself, and Jack Harris, though he to be sure was a big boy, was going to have a real old-fashioned flint-lock musket. However, I didn’t mean to let this drawback destroy my happiness. I had one charge of powder stowed away in the little brass pistol which I brought from New Orleans, and was bound to make a noise in the world once, if I never did again.

It was a custom observed from time immemorial for the towns-boys to have a bonfire on the Square on the midnight before the Fourth. I didn’t ask the Captain’s leave to attend this ceremony, for I had a general idea that he wouldn’t give it. If the Captain, I reasoned, doesn’t forbid me, I break no orders by going. Now this was a specious line of argument, and the mishaps that befell me in consequence of adopting it were richly deserved.

On the evening of the 3d I retired to bed very early, in order to disarm suspicion. I didn’t sleep a wink, waiting for eleven o’clock to come round; and I thought it never would come round, as I lay counting from time to time the slow strokes of the ponderous bell in the steeple of the Old North Church. At length the laggard hour arrived. While the clock was striking I jumped out of bed and began dressing.

My grandfather and Miss Abigail were heavy sleepers, and I might have stolen down stairs and out at the front door undetected; but such a commonplace proceeding did not suit my adventurous disposition. I fastened one end of a rope (it was a few yards cut from Kitty Collins’s clothes-line) to the bedpost nearest the window, and cautiously climbed out on the wide pediment over the hall door. I had neglected to knot the rope; the result was, that, the moment I swung clear of the pediment, I descended like a flash of lightning, and warmed both my hands smartly. The rope moreover was four or five feet too short; so I got a fall that would have proved serious had I not tumbled into the middle of one of the big rose-bushes growing on either side of the steps.

I scrambled out of that without delay, and was congratulating myself on my good luck, when I saw by the light of the setting moon the form of a man leaning over the garden gate. It was one of the town watch, who had probably been observing my operations with curiosity. Seeing no chance of escape, I put a bold face on the matter and walked directly up to him.

“What on airth air you a doin’?” asked the man, grasping the collar of my jacket.

“I live here, sir, if you please,” I replied, “and am going to the bonfire. I didn’t want to wake up the old folks, that’s all.”

The man cocked his eye at me in the most amiable manner, and released his hold.

“Boys is boys,” he muttered. He didn’t attempt to stop me as I slipped through the gate.

Once beyond his clutches, I took to my heels and soon reached the Square, where I found forty or fifty fellows assembled, engaged in building a pyramid of tar-barrels. The palms of my hands still tingled so that I couldn’t join in the sport. I stood in the doorway of the Nautalis Bank, watching the workers, among whom I recognized lots of my schoolmates. They looked like a legion of imps, coming and going in the twilight, busy in raising some infernal edifice. What a Babel of voices it was, everybody directing everybody else, and everybody doing everything wrong!

When all was prepared, somebody applied a match to the sombre pile. A fiery tongue thrust itself out here and there, then suddenly the whole fabric burst into flames, blazing and crackling beautifully. This was a signal for the boys to join hands and dance around the burning barrels, which they did shouting like mad creatures. When the fire had burnt down a little, fresh staves were brought and heaped on the pyre. In the excitement of the moment I forgot my tingling palms, and found myself in the thick of the carousal.

Before we were half ready, our combustible material was expended, and a disheartening kind of darkness settled down upon us. The boys collected together here and there in knots, consulting as to what should be done. It yet lacked four or five hours of daybreak, and none of us were in the humor to return to bed. I approached one of the groups standing near the town-pump, and discovered in the uncertain light of the dying brands the figures of Jack Harris, Phil Adams, Harry Blake, and Pepper Whitcomb, their faces streaked with perspiration and tar, and their whole appearance suggestive of New Zealand chiefs.

“Hullo! here’s Tom Bailey!” shouted Pepper Whitcomb; “he’ll join in!”

Of course he would. The sting had gone out of my hands, and I was ripe for anything,—none the less ripe for not knowing what was on the tapis. After whispering together for a moment, the boys motioned me to follow them.

We glided out from the crowd and silently wended our way through a neighboring alley, at the head of which stood a tumble-down old barn, owned by one Ezra Wingate. In former days this was the stable of the mail-coach that ran between Rivermouth and Boston. When the railroad superseded that primitive mode of travel, the lumbering vehicle was rolled into the barn, and there it stayed. The stage-driver, after prophesying the immediate downfall of the nation, died of grief and apoplexy, and the old coach followed in his wake as fast as it could by quietly dropping to pieces. The barn had the reputation of being haunted, and I think we all kept very close together when we found ourselves standing in the black shadow cast by the tall gable. Here, in a low voice, Jack Harris laid bare his plan, which was to burn the ancient stage-coach.

“The old trundle-cart isn’t worth twenty-five cents,” said Jack Harris, “and Ezra Wingate ought to thank us for getting the rubbish out of the way. But if any fellow here doesn’t want to have a hand in it, let him cut and run, and keep a quiet tongue in his head ever after.”

With this he pulled out the staples that held the rusty padlock, and the big barn-door swung slowly open. The interior of the stable was pitch-dark, of course. As we made a movement to enter, a sudden scrambling, and the sound of heavy bodies leaping in all directions, caused us to start back in terror.

“Rats!” cried Phil Adams.

“Bats!” exclaimed Harry Blake.

“Cats!” suggested Jack Harris. “Who’s afraid?”

Well, the truth is, we were all afraid; and if the pole of the stage had not been lying close to the threshold, I don’t believe anything on earth would have induced us to cross it. We seized hold of the pole-straps and succeeded with great trouble in dragging the coach out. The two fore wheels had rusted to the axle-tree, and refused to revolve. It was the merest skeleton of a coach. The cushions had long since been removed, and the leather hangings had crumbled away from the worm-eaten frame. A load of ghosts and a span of phantom horses to drag them would have made the ghastly thing complete.

Luckily for our undertaking, the stable stood at the top of a very steep hill. With three boys to push behind, and two in front to steer, we started the old coach on its last trip with little or no difficulty. Our speed increased every moment, and, the fore wheels becoming unlocked as we arrived at the foot of the declivity, we charged upon the crowd like a regiment of cavalry, scattering the people right and left. Before reaching the bonfire, to which some one had added several bushels of shavings, Jack Harris and Phil Adams, who were steering, dropped on the ground, and allowed the vehicle to pass over them, which it did without injuring them; but the boys who were clinging for dear life to the trunk-rack behind fell over the prostrate steersmen, and there we all lay in a heap, two or three of us quite picturesque with the nose-bleed.

The coach, with an intuitive perception of what was expected of it, plunged into the centre of the kindling shavings, and stopped. The flames sprung up and clung to the rotten woodwork, which burned like tinder. At this moment a figure was seen leaping wildly from the inside of the blazing coach. The figure made three bounds towards us, and tripped over Harry Blake. It was Pepper Whitcomb, with his hair somewhat singed, and his eyebrows completely scorched off!

Pepper had slyly ensconced himself on the back seat before we started, intending to have a neat little ride down hill, and a laugh at us afterwards. But the laugh, as it happened, was on our side, or would have been, if half a dozen watchmen had not suddenly pounced down upon us, as we lay scrambling on the ground, weak with our mirth over Pepper’s misfortune. We were collared and marched off before we well knew what had happened.

The abrupt transition from the noise and light of the Square to the silent, gloomy brick room in the rear of the Meat Market seemed like the work of enchantment. We stared at each other aghast.

“Well,” remarked Jack Harris, with a sickly smile, “this is a go!”

“No go, I should say,” whimpered Harry Blake, glancing at the bare brick walls and the heavy iron-plated door.

“Never say die,” muttered Phil Adams, dolefully.

The bridewell was a small, low-studded chamber built up against the rear end of the Meat Market, and approached from the Square by a narrow passage-way. A portion of the room was partitioned off into eight cells, numbered, each capable of holding two persons. The cells were full at the time, as we presently discovered by seeing several hideous faces leering out at us through the gratings of the doors.

A smoky oil-lamp in a lantern suspended from the ceiling threw a flickering light over the apartment, which contained no furniture excepting a couple of stout wooden benches. It was a dismal place by night, and only little less dismal by day, for the tall houses surrounding “the lock-up” prevented the faintest ray of sunshine from penetrating the ventilator over the door,—a long narrow window opening inward and propped up by a piece of lath.

As we seated ourselves in a row on one of the benches, I imagine that our aspect was anything but cheerful. Adams and Harris looked very anxious, and Harry Blake, whose nose had just stopped bleeding, was mournfully carving his name, by sheer force of habit, on the prison-bench. I don’t think I ever saw a more “wrecked” expression on any human countenance than Pepper Whitcomb’s presented. His look of natural astonishment at finding himself incarcerated in a jail was considerably heightened by his lack of eyebrows. As for me, it was only by thinking how the late Baron Trenck would have conducted himself under similar circumstances that I was able to restrain my tears.

None of us were inclined to conversation. A deep silence, broken now and then by a startling snore from the cells, reigned throughout the chamber. By and by, Pepper Whitcomb glanced nervously towards Phil Adams and said, “Phil, do you think they will—hang us?”

“Hang your grandmother!” returned Adams, impatiently; “what I’m afraid of is that they’ll keep us locked up until the Fourth is over.”

“You ain’t smart ef they do!” cried a voice from one of the cells. It was a deep bass voice that sent a chill through me.

“Who are you?” said Jack Harris, addressing the cells in general; for the echoing qualities of the room made it difficult to locate the voice.

“That don’t matter,” replied the speaker, putting his face close up to the gratings of No. 3, “but ef I was a youngster like you, free an’ easy outside there, with no bracelets* on, this spot wouldn’t hold me long.”

“That’s so!” chimed several of the prison-birds, wagging their heads behind the iron lattices.

“Hush!” whispered Jack Harris, rising from his seat and walking on tip-toe to the door of cell No. 3. “What would you do?”

“Do? Why, I’d pile them ’ere benches up agin that ’ere door, an’ crawl out of that ’ere winder in no time. That’s my adwice.”

“And wery good adwice it is, Jim,” said the occupant of No. 5, approvingly.

Jack Harris seemed to be of the same opinion, for he hastily placed the benches one on the top of another under the ventilator, and, climbing up on the highest bench, peeped out into the passage-way.

“If any gent happens to have a ninepence about him,” said the man in cell No. 3, “there’s a sufferin’ family here as could make use of it. Smallest favors gratefully received, an’ no questions axed.”

This appeal touched a new silver quarter of a dollar in my trousers-pocket; I fished out the coin from a mass of fireworks, and gave it to the prisoner. He appeared to be such a good-natured fellow that I ventured to ask what he had done to get into jail.

“Intirely innocent. I was clapped in here by a rascally nevew as wishes to enjoy my wealth afore I’m dead.”

“Your name, sir?” I inquired, with a view of reporting the outrage to my grandfather and having the injured person reinstated in society.

“Git out, you insolent young reptyle!” shouted the man, in a passion. I retreated precipitately, amid a roar of laughter from the other cells.

“Can’t you keep still?” exclaimed Harris, withdrawing his head from the window.

A portly watchman usually sat on a stool outside the door day and night; but on this particular occasion, his services being required elsewhere, the bridewell had been left to guard itself.

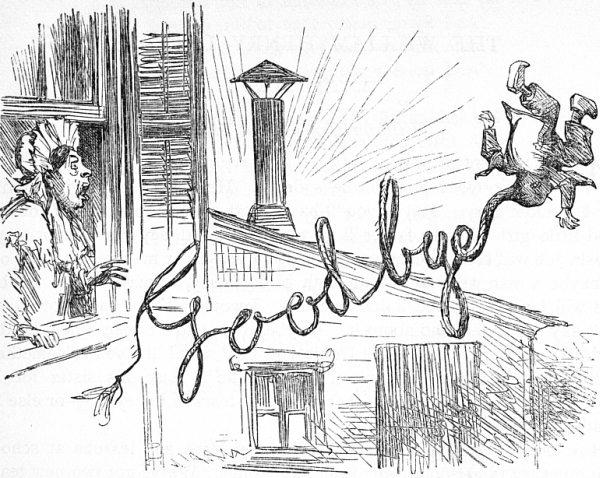

“All clear,” whispered Jack Harris, as he vanished through the aperture and dropped gently on the ground outside. We all followed him expeditiously,—Pepper Whitcomb and myself getting stuck in the window for a moment in our frantic efforts not to be last.

“Now, boys, everybody for himself!”

|

Handcuffs. |

The sun cast a broad column of quivering gold across the river at the foot of our street, just as I reached the doorstep of the Nutter House. Kitty Collins, with her dress tucked about her so that she looked as if she had on a pair of calico trousers, was washing off the sidewalk.

“Arrah, you bad boy!” cried Kitty, leaning on the mop-handle, “the Capen has jist been askin’ for you. He’s gone up town, now. It’s a nate thing you done with my clothes-line, and it’s me you may thank for gettin’ it out of the way before the Capen come down.”

The kind creature had hauled in the rope, and my escapade had not been discovered by the family; but I knew very well that the burning of the stage-coach, and the arrest of the boys concerned in the mischief, were sure to reach my grandfather’s ears sooner or later.

“Well, Thomas,” said the old gentleman, an hour or so afterwards, beaming upon me benevolently across the breakfast-table, “you didn’t wait to be called this morning.”

“No, sir,” I replied, growing very warm, “I took a little run up town to see what was going on.”

I didn’t say anything about the little run I took home again!

“They had quite a time on the Square last night,” remarked Captain Nutter, looking up from the “Rivermouth Barnacle,” which was always placed beside his coffee-cup at breakfast.

I felt that my hair was preparing to stand on end.

“Quite a time,” continued my grandfather. “Some boys broke into Ezra Wingate’s barn and carried off the old stage-coach. The young rascals! I do believe they’d burn up the whole town if they had their way.”

With this he resumed the paper. After a long silence he exclaimed, “Hullo!”—upon which I nearly fell off the chair.

“ ‘Miscreants unknown,’ ” read my grandfather, following the paragraph with his forefinger; “ ‘escaped from the bridewell, leaving no clew to their identity, except the letter H, cut on one of the benches.’ ‘Five dollars reward offered for the apprehension of the perpetrators.’ Sho! I hope Wingate will catch them.”

I don’t see how I continued to live, for on hearing this the breath went entirely out of my body. I beat a retreat from the room as soon as I could, and flew to the stable with a misty intention of mounting Gypsy and escaping from the place. I was pondering what steps to take, when Jack Harris and Charley Marden entered the yard.

“I say,” said Harris, as blithe as a lark, “has old Wingate been here?”

“Been here?” I cried. “I should hope not!”

“The whole thing’s out, you know,” said Harris, pulling Gypsy’s forelock over her eyes and blowing playfully into her nostrils.

“You don’t mean it!” I gasped.

“Yes, I do, and we’re to pay Wingate three dollars apiece. He’ll make rather a good spec out of it.”

“But how did he discover that we were the—the miscreants?” I asked, quoting mechanically from the “Rivermouth Barnacle.”

“Why, he saw us take the old ark, confound him! He’s been trying to sell it any time these ten years. Now he has sold it to us. When he found that we had slipped out of the Meat Market, he went right off and wrote the advertisement offering five dollars reward; though he knew well enough who had taken the coach, for he came round to my father’s house before the paper was printed to talk the matter over. Wasn’t the governor mad, though! But it’s all settled, I tell you. We’re to pay Wingate fifteen dollars for the old go-cart, which he wanted to sell the other day for seventy-five cents, and couldn’t. It’s a downright swindle. But the funny part of it is to come.”

“O, there’s a funny part to it, is there?” I remarked bitterly.

“Yes. The moment Bill Conway saw the advertisement, he knew it was Harry Blake who cut that letter H on the bench; so off he rushes up to Wingate—kind of him, wasn’t it?—and claims the reward. ‘Too late, young man,’ says old Wingate, ‘the culprits has been discovered.’ You see Sly-boots hadn’t any intention of paying that five dollars.”

Jack Harris’s statement lifted a weight from my bosom. The article in the “Rivermouth Barnacle” had placed the affair before me in a new light. I had thoughtlessly committed a grave offence. Though the property in question was valueless, we were clearly wrong in destroying it. At the same time Mr. Wingate had tacitly sanctioned the act by not preventing it when he might easily have done so. He had allowed his property to be destroyed in order that he might realize a large profit.

Without waiting to hear more, I went straight to Captain Nutter, and, laying my remaining three dollars on his knee, confessed my share in the previous night’s transaction.

The Captain heard me through in profound silence, pocketed the bank-notes, and walked off without speaking a word. He had punished me in his own whimsical fashion at the breakfast-table, for, at the very moment he was harrowing up my soul by reading the extracts from the “Rivermouth Barnacle,” he not only knew all about the bonfire, but had paid Ezra Wingate his three dollars. Such was the duplicity of that aged impostor!

I think Captain Nutter was justified in retaining my pocket-money, as additional punishment, though the possession of it later in the day would have got me out of a difficult position, as the reader will see further on.

I returned with a light heart and a large piece of punk to my friends in the stable-yard, where we celebrated the termination of our trouble by setting off two packs of fire-crackers in an empty wine-cask. They made a prodigious racket, but failed somehow to fully express my feelings. The little brass pistol in my bedroom suddenly occurred to me. It had been loaded I don’t know how many months, long before I left New Orleans, and now was the time, if ever, to fire it off. Muskets, blunderbusses, and pistols were banging away lively all over town, and the smell of gunpowder, floating on the air, set me wild to add something respectable to the universal din.

When the pistol was produced, Jack Harris examined the rusty cap and prophesied that it would not explode. “Never mind,” said I, “let’s try it.”

I had fired the pistol once, secretly, in New Orleans, and, remembering the noise it gave birth to on that occasion, I shut both eyes tight as I pulled the trigger. The hammer clicked on the cap with a dull, dead sound. Then Harris tried it; then Charley Marden; then I took it again, and after three or four trials was on the point of giving it up as a bad job, when the obstinate thing went off with a tremendous explosion, nearly jerking my arm from the socket. The smoke cleared away, and there I stood with the stock of the pistol clutched convulsively in my hand,—the barrel, lock, trigger, and ramrod having vanished into thin air.

“Are you hurt?” cried the boys, in one breath.

“N—no,” I replied, dubiously, for the concussion had bewildered me a little.

When I realized the nature of the calamity, my grief was excessive. I can’t imagine what led me to do so ridiculous a thing, but I gravely buried the remains of my beloved pistol in our back garden, and erected over the mound a slate tablet to the effect that “Mr. Barker, formerly of new orleans, was Killed accidentally on the Fourth of july, 18— in the 2nd year of his Age.”* Binny Wallace, arriving on the spot just after the disaster, and Charley Marden (who enjoyed the obsequies immensely), acted with me as chief mourners. I, for my part, was a very sincere one.

As I turned away in a disconsolate mood from the garden, Charley Marden remarked that he shouldn’t be surprised if the pistol-but took root and grew into a mahogany-tree or something. He said he once planted an old musket-stock, and shortly afterwards a lot of shoots sprung up! Jack Harris laughed; but neither I nor Binny Wallace saw Charley’s wicked joke.

We were now joined by Pepper Whitcomb, Fred Langdon, and several other desperate characters, on their way to the Square, which was always a busy place when public festivities were going on. Feeling that I was still in disgrace with the Captain, I thought it politic to ask his consent before accompanying the boys. He gave it with some hesitation, advising me to be careful not to get in front of the firearms. Once he put his fingers mechanically into his vest-pocket and half drew forth some dollar-bills, then slowly thrust them back again as his sense of justice overcame his genial disposition. I guess it cut the old gentleman to the heart to be obliged to keep me out of my pocket-money. I know it did me. However, as I was passing through the hall, Miss Abigail, with a very severe cast of countenance, slipped a bran-new quarter into my hand. We had silver currency in those days, thank Heaven!

Great were the bustle and confusion on the Square. By the way, I don’t know why they called this large open space a square, unless because it was an oval,—an oval formed by the confluence of half a dozen streets, now thronged by crowds of smartly dressed towns-people and country folks; for Rivermouth on the Fourth was the centre of attraction to the inhabitants of the neighboring villages.

On one side of the Square were twenty or thirty booths arranged in a semi-circle, gay with little flags, and seductive with lemonade, ginger-beer, and seed-cakes. Here and there were tables at which could be purchased the smaller sort of fireworks, such as pin-wheels, serpents, double-headers, and punk warranted not to go out. Many of the adjacent houses made a pretty display of bunting, and across each of the streets opening on the Square was an arch of spruce and evergreen, blossoming all over with patriotic mottoes and paper roses.

It was a noisy, merry, bewildering scene as we came upon the ground. The incessant rattle of small arms, the booming of the twelve-pounder firing on the Mill Dam, and the silvery clangor of the church-bells ringing simultaneously,—not to mention an ambitious brass-band that was blowing itself to pieces on a balcony,—were enough to drive one distracted. We amused ourselves for an hour or two, darting in and out among the crowd and setting off our crackers. At one o’clock the Hon. Hezekiah Elkins mounted a platform in the middle of the Square and delivered an oration, to which his fellow-citizens didn’t pay much attention, having all they could do to dodge the squibs that were set loose upon them by mischievous boys stationed on the surrounding house-tops.

Our little party, which had picked up recruits here and there, not being swayed by eloquence, withdrew to a booth on the outskirts of the crowd, where we regaled ourselves with root-beer at two cents a glass. I recollect being much struck by the placard surmounting this tent:—

Root Beer

Sold Here.

It seemed to me the perfection of pith and poetry. What could be more terse? Not a word to spare, and yet everything fully expressed. Rhyme and rhythm faultless. It was a delightful poet who made those verses. As for the beer itself,—that, I think, must have been made from the root of all evil! A single glass of it insured an uninterrupted pain for twenty-four hours. The influence of my liberality working on Charley Marden,—for it was I who paid for the beer,—he presently invited us all to take an ice-cream with him at Pettingil’s saloon. Pettingil was the Delmonico of Rivermouth. He furnished ices and confectionery for aristocratic balls and parties, and didn’t disdain to officiate as leader of the orchestra at the same; for Pettingil played on the violin, as Pepper Whitcomb described it, “like Old Scratch.”

Pettingil’s confectionery store was on the corner of Willow and High Streets. The saloon, separated from the shop by a flight of three steps leading to a door hung with faded red drapery, had about it an air of mystery and seclusion quite delightful. Four windows, also draped, faced the side-street, affording an unobstructed view of Marm Hatch’s back yard, where a number of inexplicable garments on a clothes-line were always to be seen careering in the wind.

There was a lull just then in the ice-cream business, it being dinner-time, and we found the saloon unoccupied. When we had seated ourselves around the largest marble-topped table, Charley Marden in a manly voice ordered twelve sixpenny ice-creams, “strawberry and verneller mixed.”

It was a magnificent sight, those twelve chilly glasses entering the room on a waiter, the red and white custard rising from each glass like a church-steeple, and the spoon-handle shooting up from the apex like a spire. I doubt if a person of the nicest palate could have distinguished, with his eyes shut, which was the vanilla and which the strawberry; but, if I could at this moment obtain a cream tasting as that did, I would give five dollars for a very small quantity.

We fell to with a will, and so evenly balanced were our capabilities that we finished our creams together, the spoons clinking in the glasses like one spoon.

“Let’s have some more!” cried Charley Marden, with the air of Aladdin ordering up a fresh hogshead of pearls and rubies. “Tom Bailey, tell Pettingil to send in another round.”

Could I credit my ears? I looked at him to see if he were in earnest. He meant it. In a moment more I was leaning over the counter giving directions for a second supply. Thinking it would make no difference to such a gorgeous young sybarite as Marden, I took the liberty of ordering ninepenny creams this time.

On returning to the saloon, what was my horror at finding it empty!

There were the twelve cloudy glasses, standing in a circle on the sticky marble slab, and not a boy to be seen. A pair of hands letting go their hold on the window-sill outside explained matters. I had been made a victim.

I couldn’t stay and face Pettingil, whose peppery temper was well known among the boys. I hadn’t a cent in the world to appease him. What should I do? I heard the clink of approaching glasses,—the ninepenny creams. I rushed to the nearest window. It was only five feet to the ground. I threw myself out as if I had been an old hat.

Landing on my feet, I fled breathlessly down High Street, through Willow, and was turning into Brierwood Place when the sound of several voices, calling to me in distress, stopped my progress.

“Look out, you fool! the mine! the mine!” yelled the warning voices.

Several men and boys were standing at the head of the street, making insane gestures to me to avoid something. But I saw no mine, only in the middle of the road in front of me was a common flour-barrel, which, as I gazed at it, suddenly rose into the air with a terrific explosion. I felt myself thrown violently off my feet. I remember nothing else, excepting that, as I went up, I caught a momentary glimpse of Ezra Wingate leering though his shop window like an avenging spirit.

For an account of what followed, I am indebted to hearsay, for I was insensible when the people picked me up and carried me home on a shutter borrowed from the proprietor of Pettingil’s saloon. I was supposed to be killed, but happily (happily for me, at least) I was merely stunned. I lay in a semi-unconscious state until eight o’clock that night, when I attempted to speak. Miss Abigail, who watched by the bedside, put her ear down to my lips and was saluted with these remarkable words:—

“Root Beer

Sold Here!”

T. B. Aldrich.

|

This inscription is copied from a triangular-shaped piece of slate, still preserved in the garret of the Nutter House, together with the pistol-but itself, which was subsequently dug up for a post-mortem examination. |

Before telling you what corals are, I will tell you what they are not, because a very mistaken impression prevails about their nature. It is common to hear people speak of coral insects; and coral stocks with their innumerable little pits and partitions have been compared to a honeycomb.* This is a mistake. There is no such animal as a coral insect; and the coral stock, instead of being, like the honeycomb, a kind of house so constructed that the creature inhabiting it can pass in and out at will, consists of the solid parts of the coral animals themselves. A coral can no more separate itself from the structure of which it forms a part than a bird can fly away from its bones.

But, though the coral is no insect, it resembles very closely a kind of animal which is familiar, I have no doubt, to such of my young readers as live on the sea-shore. To those whose home is in the inland country, or in the far West, where the prairie and its distant boundary line are the substitutes for our great ocean plain and its horizon, I shall find it more difficult to explain my subject. Yet even they may know the sea-anemone, at least by name.

It is not strange that this animal should have been called after a flower, though it bears no especial resemblance to an anemone. Yet when all its feelers are spread, forming a thick wreath around the summit of the body, it may well remind one of any cup-shaped flower surrounded by a crown of finely-cut colored leaves. In the different anemones these feelers are of very various tints; in some they are pure white, in others pink, orange, purple, violet, or variegated, as the case may be. They differ in intensity of color in proportion as they are more or less open.

I wish with all my heart that, instead of talking to you about them, I could take you to a grotto I know very well, on East Point, at Nahant. It is a little difficult of approach, only visible at low tide; and, to reach it, you must clamber over steep, slippery rocks, covered with sea-weed.

This grotto is a nook in the rocks, some five or six feet long, and perhaps about three feet in height, and open from end to end. In order to have a good view of the interior, you must stoop down in front of the opening, and then, if the sun is shining through, you will see a wonderful display of color. The walls and roof are closely studded with sea-anemones, and when they are all expanded the grotto seems lined with a close mosaic work of every hue. At first sight, you may think this living inlaid work on wall and ceiling as motionless as the inanimate rock on which it rests. Watch it for a little while. You will find that these soft, many-colored wreaths of feelers stir: they contract and expand at the will of the animal, are sensitive to influences from without, feel the warmth of the sunshine and the coolness of the fresh wave as it breaks over them, are conscious of the approach of danger or of anything floating in the water which may serve them as food. When all the conditions are genial to them, and they feel animated and active, they stretch their bodies to their full height, expand all their feelers, and seem to enjoy their life.

Figure 1. Sea-anemone, open.

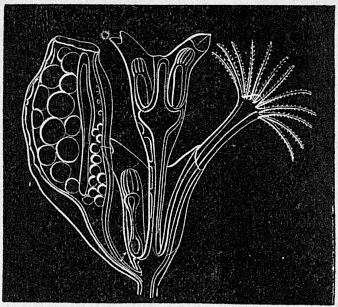

In Figure 1 you have the picture of a sea-anemone when he looks his best. The centre of the space lying amid the wreath of feelers represents the mouth. Through that the animal receives its food, and drops it into a kind of sac which hangs in the middle of the body and into which the mouth opens. That sac has a hole in the bottom, through which the food then passes into the main body and circulates all through it, nourishing every part. This sac is called the digestive sac, and serves as a stomach.

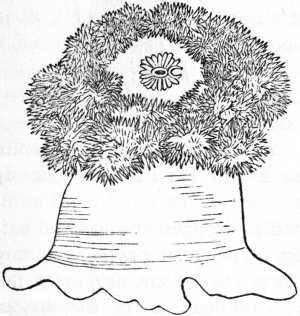

In Figure 2 you have the same animal closed,—with all his feelers drawn in and snugly packed away. In the latter condition he is a very ugly fellow, a dingy lump of jelly-like substance; but with his feelers expanded, and his body erect, he is, on the contrary, a very beautiful object, and well deserves his name.

Figure 2. Sea-anemone, closed.

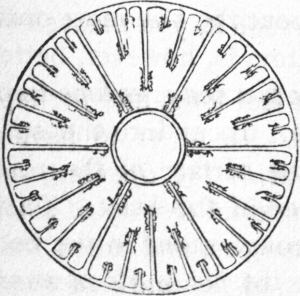

The internal structure of this animal is very curious. He is divided from top to bottom by partitions, and, if you were to cut him across, you would find that these partitions extend from the centre of the body outward, like the spokes of a wheel. Imagine a wheel, instead of being a simple circle, to be a round box open at the top and standing on the lower end, the spokes dividing it just as they now do, except that they would also extend from the top to the bottom of the box. Such a figure gives you a rough idea of the internal structure of a sea-anemone, only that in the centre of the wheel, instead of what we call the hub, you must put an open-mouthed bag, hanging between the spokes or partitions.

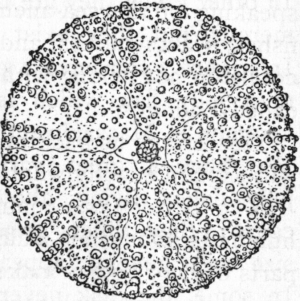

Figure 3. Transverse cut of Sea-anemone.

Figure 3 represents a cut across the body of a sea-anemone. The circular space in the centre represents the opening of the bag which is the digestive sac or stomach; the spokes represent the partitions which run from the summit to the base of the animal, and from his outer surface inward.

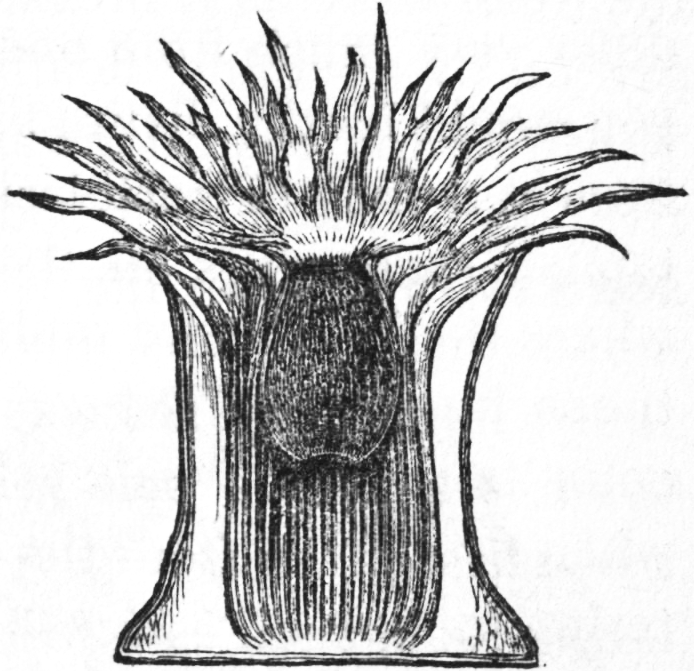

Figure 4 represents a cut through the body of the same animal, as seen from top to bottom; the lines continued from the feelers downward represent the partitions. In Figure 3 you see the thickness of the partitions, the width of the spaces between them, and the opening of the digestive sac; in Figure 4 you see the length of the partitions and of the spaces between them, with the digestive sac hanging within. If you examine Figure 4 carefully, you will see that all parts of the body communicate, so that any food taken in at the mouth may circulate in every direction throughout the interior. The partitions do not start exactly from the middle of the body; they leave, on the contrary, a free space in the centre. In this space the sac hangs to a certain distance, as you see. Below the sac the space is quite unoccupied, and the hole in the digestive sac opens into it. Thus all food taken into the mouth after being digested is dropped through the bottom of the sac into the lower part of the body. Thence it passes, not only in and out between the partitions, but up into the feelers also; for the feelers are hollow, and are, indeed, merely continuations of the spaces divided off by the partitions.

Figure 4. View of the internal structure of a Sea-anemone, seen from base to summit.

In Figure 3 you see only a few partitions, and when the animal is young their number is very limited. But as he grows older they increase indefinitely, so that they cannot be counted. You may judge how numerous they are, if you remember that every feeler or tentacle composing the thick wreath on the top of the body is hollow, and opens into one of the spaces lying between two partitions.

I have been so minute in describing the sea-anemone because very few if any of you can have seen a living coral, and I could think of no other animal, closely resembling the coral, with which some of my readers at least were likely to be familiar. I would advise those who live near the sea-shore, and can easily obtain specimens, to keep one or more sea-anemones alive during the summer, and watch them. Do not think that for this object it is necessary to have an elaborate aquarium: a glass bowl, of about the size of an ordinary salad-dish, is all you need. A jar with a flat bottom is, however, better than a bowl with sloping sides. You can easily separate a sea-anemone from the rock by passing a knife under him. Be careful not to cut into the substance of the animal; you can force the knife along the surface of the rock between it and the anemone without injuring the latter in the least. Then fill your glass jar with fresh sea-water, put a piece of rough stone in the bottom, and place your anemone upon it. Add a few bits of floating sea-weed, and you have all you need to keep your specimen alive for a number of days or even for weeks, if you change the water often enough. You can watch him as he contracts and expands his feelers. You can feed him with bits of oysters or mussels or common cockles, and see how he catches his food between his feelers, carries it to his mouth, and gradually absorbs it.

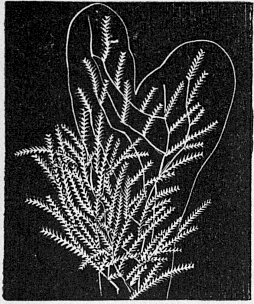

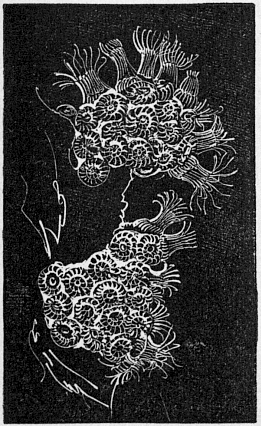

Figure 5. Branch from a colony of Sertularians, natural size.

There are a great many animals made upon the same plan as the sea-anemone,—most of them inhabiting the sea or living along the coast. They differ very much from one another in external appearance. Some of them you would hardly distinguish from sea-weeds; such is the little branch taken from a colony of sertularians represented in Figure 5.† These animals establish themselves on the broad blades of some of our common sea-weeds, where they grow and multiply with great rapidity. They are often found on those huge, ugly sea-weeds known as “the Devil’s apron-strings.” Their color is usually a pale yellow, though sometimes they are pure white; and when first taken from the water a fragment from such a colony has a glittering look, such as a white frost leaves on a spray of grass.

This seeming branch, which looks so like a twig broken from some delicate plant, is made up of hundreds of living beings, who lead a common life, and whose bodies open into each other. Tiny as they are, they all have their digestive sacs in the centre of the body, and their wreath of feelers above.

Figure 6. Fragment of the same colony, magnified.

Figure 6 shows you a little piece, highly magnified, from the branch represented in Figure 5. These colonies have such a complicated existence that it would not be easy to make you understand all their parts without long and tiresome explanations. But if you will look at Figure 5 with me for a moment, I will say one word about it. Do you see that on the left-hand side is a cup-shaped bud (naturalists call them buds because they look like buds on a stem), and that it is filled with little round balls? Those are eggs; that bud will burst, the eggs will escape into the water, and will, in due time, develop into animals. On the right-hand side of the stem is another of the members of this little community, with all its feelers spread, while between the two, that is, between the one which holds the eggs and the one with its feelers extended, is the central animal into which both the others open. The last two, the central one, and the one with feelers, will never produce any eggs, because that work does not belong to them.

It is a curious thing that in these communities the work of life is distributed among the different members. In some of them this division of work is carried very far; certain individuals lay the eggs, others seem to be chiefly mouths and stomachs, and they receive and digest the food, and circulate it among the rest; others catch the food and pass it on to the open-mouthed individuals. All have their special work, and no one interferes with his neighbor.

There are many such communities living about our sea-shore, differing somewhat in the little beings which compose them, but all agreeing in their general structure. I think it would interest those of you who like to watch animals to keep one or two such branches with your sea-anemone. Or it would be still better to have a fragment in a separate glass bowl; a white glass finger-bowl would be just the thing. It is easier to keep your specimens apart. If you combine them all in one aquarium, unless you understand perfectly how to arrange it, the water soon becomes thick, and then, in order to change it, you must move all your animals. We are apt to be too elaborate in our arrangements for studies of this kind. A table in a window, with a few glass jars upon it, gives you all you need for a summer’s observation. If you can add a small microscope to your establishment, and have some friend to teach you how to use it, it will be of great service. Without that, you cannot examine the different members of your community of sertularians, though you may be able to distinguish them from each other with the naked eye.

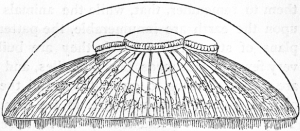

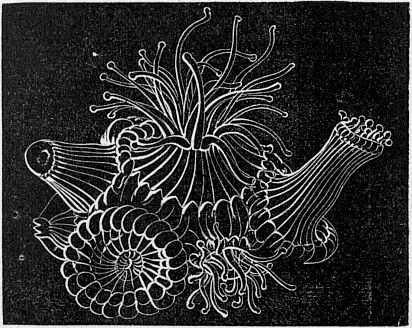

Figure 7. Jelly-Fish,—Aurelia.

Next among the animals which are allied to the sea-anemones by their structure are the jelly-fishes. They are not fishes, and do not resemble them in the least, but are so called because they consist of a jelly-like substance and live in the sea. They are semicircular or hemispherical in shape, their body forming a gelatinous transparent disk, from the margin of which hang more or less numerous feelers. Sometimes these feelers grow so thickly that they resemble a delicate fringe all around the edge of the body. In other kinds they are not numerous, but they exist in all. In Figure 7 you have a picture of a jelly-fish which is very common in Massachusetts Bay. We have a great variety of jelly-fishes living about our coast; they differ greatly in size and general appearance. In some, the disk never grows to be larger than a thimble or a walnut; in others, it measures two or three feet across, and the feelers hanging from it are many yards in length. When bathing or swimming, it is sometimes dangerous to be caught in these long feelers; they have a stinging quality like nettles, and if entangled in them you may become so benumbed as to be unable to extricate yourself.

Curious to relate, these jelly-fishes, even the larger among them, are the offspring of small creatures similar to those which compose the communities we have been talking about. Do you remember the eggs with which one of the animals in Figure 5 is filled? Those eggs will not grow into beings like those from which they were born. They will develop into jelly-fishes,—the jelly-fishes in their turn will lay eggs, and those eggs will grow into communities like the one which produced the jelly-fishes.

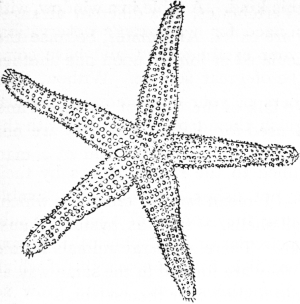

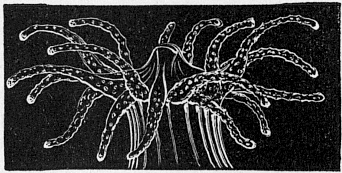

Figure 8. Star-fish.

Next comes a group of animals allied to all those described above, though so unlike in appearance that I dare say you will find it difficult to believe the statement. Some of them have the outline of a star; and perhaps you may know them as the so-called star-fishes.‡ We have a picture of one in Figure 8. Others are round, and from their shape are called sea-eggs. They are known also by the name of sea-urchins. Such an animal is represented in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Sea-urchin.

You see from these few specimens how greatly these animals differ in aspect. But, however various their external appearance may be, they all agree in this; namely, that the different parts of the body spread or radiate from the centre outward, and for this reason all animals constructed in this way are called Radiates. One of these days some of my readers may be naturalists; at all events, I hope that many of them will care to know something of nature and of the animals by which they are surrounded. On this account, and because it will make the study much easier, I want them to remember, that, while the animals living upon the earth are innumerable, the patterns, or plans of structure on which they are built, are very few. Quadrupeds, birds, reptiles, and fishes are made according to one pattern, and the body of man himself is constructed in the same way. They all have a backbone, built of separate pieces called vertebræ, and for this reason naturalists call them Vertebrates. They all have a bony arch above and another below that backbone, enclosing cavities which contain certain organs.

If you compare these animals for yourselves, you will find that the resemblance is carried out in all the different parts,—that, for instance, the front fin of a fish, the front paw of a reptile, the wing of a bird, the fore limb of a quadruped, and the arm of a man, are built up of similar parts. These parts are differently put together,—they are shorter or longer, narrower or wider, and joined to each other in different ways, so as to be solid and immovable in some animals, jointed and flexible in others,—but they correspond nevertheless, their general relations to each other being the same.

There is another plan for all insects, lobsters, crabs, shrimps, and worms. The number of these animals can hardly be estimated,—of insects alone, we know about a hundred and fifty thousand kinds, and these kinds are represented by myriads of individuals. Yet all these animals, from the insect to the worm, are made in the same way. Their bodies consist of a number of rings movable upon one another. They may be, like the worms, destitute of limbs, or they may have a number of legs and feelers like the lobsters and crabs, or they may have wings and legs like the insects. They may be as ugly as an earth-worm, or as beautiful and as gay in color as the brightest butterfly, but in one and all the whole body is built on the same pattern. The differences are produced, as in the Vertebrates, by a different arrangement of similar parts. All these animals are called Articulates, because the rings of which they are composed are articulated or jointed upon one another in such a way as to render them movable.

You must not be misled by names. We talk of the wing of an insect and the wing of a bird, because they are both used for flight. But they are not the same organs. The wing of a bird is much more like the arm of a man than like the wing of an insect.

There is another pattern for all shells,—I mean for the creatures which, on account of their hard envelope, we call shells,—such as oysters, clams, mussels, snails, nautili, conchs, and the like. There are many animals in this group which have no shelly covering, but they are formed in the same way as the soft bodies of those animals which build a shell over themselves.

Finally, there remains still another pattern,—the one I described when speaking of the sea-anemone. Upon this all star-fishes, sea-urchins, jelly-fishes, sea-anemones, and, lastly, corals, are constructed. Thus you see the corals do not belong with insects, but with a very different group of animals called Radiates.

This brings us back to our coral stock. As I must often use the word, I will explain exactly what I mean by stock in this sense.

A coral stock is a community of animals living together in a solid mass,—hundreds, thousands, millions, crowded together in a common life. The hard parts of their bodies make the whole mass as firm as rock, and, in the fragments of coral stock preserved in our museums or cabinets, we see only the hard parts; but when the creatures are living the surface of the community is soft and feathery,—each little animal, where it opens on the outside of the stock, being furnished, like the sea-anemone, with delicate feelers around the mouth.

On our coast we have but one species of coral. It is found about the shores of Long Island, and on the islands of Martha’s Vineyard Sound; and though it is not one of the reef-building corals, and therefore not the same as those which compose the reef of Florida, I add its picture here, because I wish, whenever I can, to talk of things which some of you at least may have opportunities of seeing in nature.

Figure 10. Astrangia stock.

Figure 11. Portion of an Astrangia stock, magnified.

Figure 10 shows you a community of Astrangia, as this coral is called. Each of the little circles on the surface marks a single animal. In some of them the feelers are drawn in, and then you see only the partitions dividing the interior of the animal, and radiating from the centre of each circle toward its outward edge. In others the feelers are extended, and in real life, being of very soft and flexible texture, they give a downy look to the surface of the stock. Figure 11 shows you several of the same animals magnified. The one placed uppermost in the group exhibits the summit of the body, where the mouth is placed. You see the feelers extended, and the partitions radiating from the central opening outward. The right-hand animal is drawn in profile, so that the partitions are seen running lengthwise from the base to the summit of the body. The feelers are almost hidden. The left-hand figure is nearly the same, except that the feelers have completely disappeared. Just below is another, which turns the summit of its body directly toward you, so that you look into the mouth; and, as the feelers are all drawn in, the radiation of the partitions is shown with remarkable distinctness.

Figure 12. Single animal from an Astrangia stock, highly magnified.

In Figure 12 you have a single animal from an Astrangia stock, magnified, with all its tentacles spread.

If I have made my explanations clear, and if you have understood the different parts shown in the figures, I think you will see that corals and sea-anemones have the same kind of structure. But there is one point in which they differ essentially, and in that difference lies the secret of the important part played by corals in the physical history of the world. It requires, however, a good deal of explanation, and my lesson in Natural History has been long enough for to-day.

In the next chapter I will take this point up again in connection with the reef-building corals, and their relation to the growth and structure of Florida.

Elizabeth C. Agassiz.

|

Even so learned an authority as Sir John Herschel, in his “Familiar Lectures on Scientific Subjects,” speaks of the work done by the “coral insects.” See Sec. I, p. 12. |

|

Colony of Dynamena pumila; natural size. |

|

They are not fishes any more than the jelly-fishes; but both received the name when their nature was not understood and all beings living in the sea were called alike. |

The buds grew green upon the boughs, the grass upon the hills,

And violets began to bud by all the brimming rills;

And a little brown sparrow came over the sea,

And another came flying his mate to be;

And they wooed and they wed, and they built a nest,

In the place which they thought was the pleasantest.

“Though any spot’s a pleasant one that’s shared with you,” said he.

“And any place where you may dwell is good enough for me,”

Said she,—

“Is good enough for me.”

But when the nest was fairly built, the violets fully blown,

A wandering cuckoo chanced that way, and spied the nest alone;

And she said to herself, “In the sunny spring,

To brood over a nest is a weary thing”;

So she went on her journey to steal and beg,

But behind in the nest left a foundling egg.

And when the sparrow-wife came back, the egg, whose could it be?

“It is not mine,” she said, “and yet it must belong to me;

’Tis here,

And must belong to me.”

So, full of patient mother-love, beneath her downy breast,

As fondly, gently as her own, the speckled egg she pressed,

Through the days with their marvellous unseen sights,

And the damp and the chill of the spring-time nights,

Until two little sparrows had burst the shell,

And the cuckoo had wakened to life as well.

His breast was bare, his wings were weak, his thoughts were only three:

“What do I want? What can I have? What will become of me?

Cuckoo!

What will become of me?”

He opened wide his bill, and cried, and called for food all day,

And from his foster-brothers’ beaks he snatched their share away.

“Were there one, only one, to be warmed and fed,

And if I were that one,” to himself he said,

“Then the doting old birds would have nothing to do

But to wait and to tend upon me! Cuckoo!

In such a close and narrow nest there is no room for three.

What do I want? What can I have? What will become of me?

Cuckoo!

What will become of me?”

He stretched his neck above the nest, he peered each way about,

If none could see, then none could say who pushed the nestlings out;

But the cuckoo was left in the nest alone,

And the share of his brothers was all his own,

And the sparrows were feeding him all day long,

And his feathers grew dark, and his wings grew strong,

And wearisome became the nest. “A stupid place!” said he.

“What do I want? What can I have? What will become of me?

Cuckoo!

What will become of me?”

The old birds called him to the bough, and taught him how to fly,

He spread his wings, and left them both without a last good-by;

And beyond the green meadow-lands wet with dew,

And the wood and the river, he passed from view.

And amid what scenes he may flit to-day,

Or his wings may rest, there is none to say;

But whereso’er that selfish heart, its thoughts are only three:

“What do I want? What can I have? What will become of me?

Cuckoo!

What will become of me?”

Marian Douglas.

“Tell us, papa,” exclaimed Willie Blake, rushing, followed by his sister, into his father’s library,—“tell us, papa, aren’t wreckers cruel people who murder and rob poor shipwrecked passengers who are washed ashore near where they live? Aren’t they, papa?”

“Where in the world did you get that idea?” asked his father.

“I was reading a story full of large pictures, and one of them showed a sailor lying on the sea-shore, and a great, ugly, rough man was about to kill him with a long knife. And the story said the sailor was a great lord in disguise, and that the wicked man was a smuggler and wrecker.”

“Ah, I see!” said his father. “You have been reading a forbidden book. From a novel, which did not profess to tell the truth, you have received a very wrong impression. I have often told you how careful you ought to be, not only as to what you learn, but from whom you learn. Books are often written by very ignorant persons. Now the one you read was written by a very ignorant person indeed, for he did not know the difference between a wrecker and a smuggler, and he has made you think them the same. If you had been older, and able to judge of what you ought to read, that mistake would have proved to you that the rest of the book was not worth reading. Smugglers and wreckers are really just as unlike in character and occupation as can be,—as different, in fact, as thieves and policemen.”

“O papa!” exclaimed both the children, and even their mother looked up from her sewing in some surprise.

“Yes,” continued Mr. Blake, “just as different. In some countries wreckers are really regular policemen. In England they are employed to watch the coast just as our policemen watch the streets. They are uniformed as policemen are, and are called ‘Coast-Guards.’ They are old sailors, and their uniform is very like a sailor’s. They wear a loose jacket like a sailor’s, and a sailor’s hat with the word ‘Coast-Guard’ printed on the band, just as you sometimes see the name of his ship printed on the sailor’s hat-band. They carry a cutlass and a pair of pistols; these are for use against smugglers. They also have a spy-glass to watch the ships at sea, and their principal duty in the day is to walk their beat on the sands or cliffs, and keep a sharp lookout to sea. We have no regular organized coast-guards in this country, the volunteer wreckers doing duty in that way. The government has at all times under pay a large force of special marine police, called revenue officers, to watch the smugglers; and they often detect and capture them in their attempts to take out or bring in goods which have not paid government duty; that is, a fee or tax which is levied to support the government. Wreckers, on the contrary, are licensed by the government to save life and property, and they have courts established to settle their claims. The government officers do not watch for them as they do for smugglers, but on the other hand the government helps them by building houses and furnishing them with boats and ropes to save life, firewood to build fires for the purpose of lighting vessels in a storm, and medicines for the sick and half-drowned people whom they rescue. Then the wreckers are paid to spy upon the smugglers, and many of the rascals are detected through the aid of honest wreckers. Besides, smugglers and wreckers do not live on the same coasts. It is necessary to the wrecker’s success in business that he should live on a dangerous coast, where wrecks are frequent. You see he lives by others’ misfortunes, and he must be where the worst wrecks take place. The smuggler lives on a part of the coast where there are no dangerous shoals and sands and rocks, and where great winds which might wreck his boat and cargo do not usually prevail; he must have a good as well as a quiet and secluded place to land in, for he has to run his cargo of smuggled goods ashore at night. Now I hope you understand that smugglers and wreckers are very different people, and that Willie’s story-telling friend was telling a huge story when he said that one man was both a smuggler and a wrecker.”

“Then are smugglers all wicked men?” asked Willie.

“Exactly,” said his papa; “they are all thieves.”

“And are the wreckers all good men?” asked Minnie.

“No, no, Minnie, not so fast. It does not follow, because their business is recognized and licensed, and is a good and proper and honorable one, that all wreckers are good men. Many of them are bad men, but there are bad men in all ranks of life. There was the professor in the college who murdered his physician, don’t you remember? And don’t you recollect about the preacher who whipped his own child to death because he wouldn’t say his prayers? They were bad men; but we must not say, therefore, that all professors and preachers are bad men. So, also, there are some bad wreckers, and as most of the people who follow that hard and dangerous life are rough, uneducated folks, I am afraid very many of them are wicked. But it does not follow that they are all so. The idea I wish to impress on you is, that the calling of the wreckers is respectable, and that the wrecking system of the country is wise and humane, whereas smuggling is in every respect disreputable and dishonest. But you will understand the character of wreckers better when I tell you where and how they live.”

The children again expressed their interest and eagerness by more cries of “O, do, papa! please do!” and were now to all appearances deeply interested in the subject. Their father soon resumed his story.

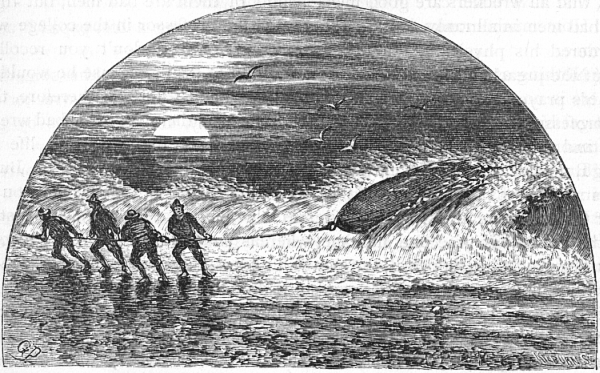

Interior of Life-car.

“There are said to be about four thousand wreckers in the United States; the most of them live along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to the Florida reefs. They and their families will number twenty-five thousand souls, all of whom make their bread by saving property from wrecked vessels. How they do this I now propose to tell you; and I can do it better with the pictures I have here than by mere words. Now here is a picture of wreckers saving life; that is, of course, the first thing they have to do when a wreck occurs.* The ship, you see, has gone ashore on the sand near the light-house, and the wreckers are preparing to give assistance to the passengers. Some of these have already been washed from the vessel, and have been thrown half alive on the beach by the great waves. Some of the wreckers are taking care of them, while others are catching a man whom a wave is washing ashore. A life-boat is ready manned to be launched as soon as the rope which a man is bringing can be attached to one end of the life-car,—the great boat-like object on the wagon with broad wheels, that will not sink in the soft, moist sand. When this is ready, the men will pull for the ship, and the rope will be taken on board. Then the life-car will be pulled through the water to the ship, while those on shore will hold on to a rope attached to their end of it. Then as many of the passengers as the life-car will hold will be put into it, and it will be closed up so that no water can get inside, and the wreckers on shore will haul it through the billows and release the poor passengers. Here is a picture of the life-car being hauled ashore, and also one showing the interior of it. It is air and water tight, but there is little danger that the inmates will smother or drown, as the boats contain air enough to last twenty-five minutes, and they are seldom in the water more than five minutes at a time.”

Hauling the Life-car ashore.

“What is the difference between a life-boat and a life-car, papa?” asked Willie, who had noticed the open boat in the picture.

“A life-car is closed,” answered his father, “while the life-boat is open. The car is a modern invention, but the life-boat is now nearly a hundred years old. The life-boat now in use is very nearly perfect, and can hardly be sunk. It is self-righting; that is, if turned over in the water, it won’t stay bottom up, but will immediately turn up all right again. Instances have been known in which sailors in a life-boat, seeing a great wave coming which was sure to upset them, have stowed themselves away under the sides or thwarts of the boat, and have come up again with the boat, having turned a summersault, and that almost without wetting their clothes!”

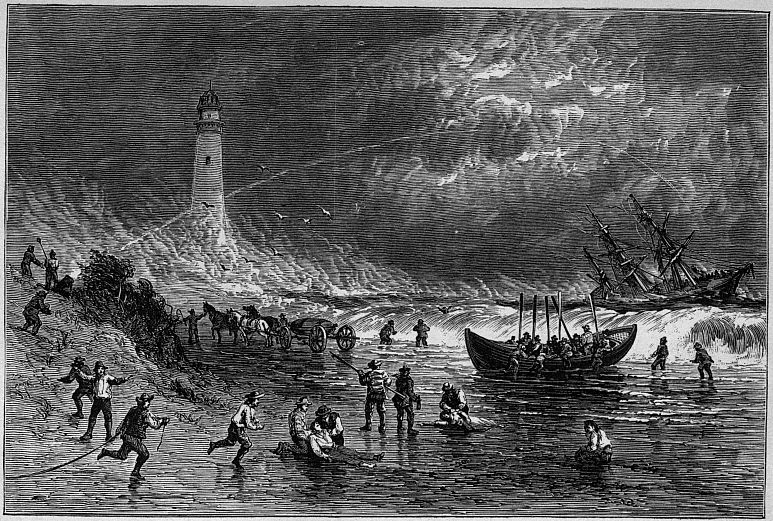

LAUNCHING THE LIFE-BOAT.

Drawn by Granville Perkins.] [See page 218 (See transcriber's note).

“O papa, papa!” cried the children, looking as if they did not know whether to believe him or not.

“You don’t believe that, do you? Yet it is all true, and the Esquimaux Indians who live on the coast of Greenland practise the feat of turning summersaults in their boats as our necromancers do other juggling feats. It is very simple, and is on the principle of the diving-bell, in which, as you know, men go down to the bottom of the ocean without getting wet. The men in the life-boats are not always so fortunate as to cling to the boat, and are often thrown into the water. They do not sink, however, for most of the crews of life-boats wear cork-jackets, which save them from sinking, and, being good swimmers, they generally soon regain the boat. When the rescued passengers are taken ashore, they are removed to the nearest house. The government has established, at various points all along the coast, houses for the shelter of wrecked passengers. Here are kept medicines, firewood, and clothing, as I have before told you. But wreckers generally carry injured persons to their own houses, where their wives and children can nurse them. Their reason for doing this is, that often persons who recover give the wreckers who have taken care of them handsome rewards.”

“How much money does a wrecker get for saving a life, papa?” asked Minnie.

“Nothing at all, unless the person saved chooses to give him something. There is no reward held out or paid for the rescue of life, but a wrecker cannot get his pay from the court for saving property, until he proves by good testimony that he helped to save life before he tried to save property.”

“But what do you mean by a court, papa? Have the wreckers courts of their own to divide the property which they save among themselves?”

“O no. You must not suppose that a wrecker is entitled to whatever he saves from a wreck. The plunder which he gets out of a wrecked ship does not belong to him, nor to the owner of the ship, nor to the men who hired the ship to carry it across the ocean. If I should send a hundred bales of cotton to Liverpool in the ship Scotia, and she should be wrecked, the cotton which the wreckers might get out of her would no longer belong to me, nor to the ship, nor to the wreckers who saved it, but to the insurance-company who insured its safe transit to Liverpool. They would pay me the whole amount of the insurance on the cotton, and then sell the damaged cotton for all they could get for it. But the wrecker would have to be paid for saving it, and the amount which would be allowed him would depend on the amount of labor and danger incurred. The United States courts would have to decide the amount, which would be called ‘Salvage.’ These courts are authorized to license wreckers and wrecking vessels, and before doing so the judges have to satisfy themselves that the person asking for a license is of good character, and that his vessel is sea-worthy; that is, a good strong one. If a wrecker embezzles any wrecked goods, or runs a vessel aground while acting as a pilot, or hires others to do it, his license may be taken away from him.”

“But, papa, is looking after wrecks all that the wreckers do?”

“O no. Most of them are fishermen besides. Their homes are always near the beach, and they can watch for wrecks and fish at the same time. At Key West, Florida, where there are a great many wreckers, they catch fish for the Cuban markets, and almost wholly supply the city of Havana with fresh fish. There are many other things which they do at odd times. One of these I think you would never guess. They write for the newspapers.”

“Write for the newspapers?”

“Or, rather, they tell others what to write. Many years ago, one of the large newspapers of the country offered to pay pilots, wreckers, and others a handsome sum for every wreck which they reported; and to this day, although the telegraph is the usual reporter, the wreckers occasionally go to the newspaper offices to give the news of a wreck. And now I believe I have told you all I know about the wreckers.”

“But not about wrecks, papa!” said Willie. “I should not suppose that enough wrecks happened to support so many people.”

“I believe I said that there were about twenty-five thousand persons dependent on the wreckers in the United States,—didn’t I?”

“Yes, sir; that’s what you said.”

“I have no doubt that there are five or six times as many in the world, and that all of them get a good living by wrecking. Of course many wrecks must therefore happen. Now how many American vessels do you suppose are wrecked every year?”

The children made various guesses, but, as they had never studied the subject, their guesses were wide of the mark; it was only time lost, so they at length gave up. Their mother, who was also interested in the story, made a slight calculation and answered, “Not more than twenty, I should say.”

“Then you would be very wide of the mark, and if you stated that for a fact you would give these young folks a very false idea. More than that number occur every month.

“Your mother can perhaps recall twenty which occurred in one year, but they were the memorable and remarkable ones in which much property and many lives were lost. Minnie might count on her fingers, little as they are, the great wrecks which we hear fully related in the daily papers, appalling whole communities with the horrors which accompany them; but many more than these really occur. It is estimated that there are about four hundred wrecks and partial wrecks of American ships every year. Now how many do you think happen in the whole world? You need not guess, for I could not tell you if you were right or wrong, as I do not know myself; but I have seen it stated that twenty-three hundred wrecks occurred in 1867 on the English coast alone; and that the average loss there is about twenty-eight hundred a year. That is eight a day, or one every three hours in the day. But these are only a few among the vessels wrecked in all seas and oceans; for in 1866 the wrecks and partial wrecks amounted to 11,711, and in 1867 to 12,513 vessels.”

The children did not know what to say to this surprising statement, so they said nothing. Finding them silent, their father continued:—

“In the kingdom of Great Britain, there is an officer whose duty it is to keep an account of all the wrecks happening on the coast of that country. Now the kingdom of Great Britain, grand as its name sounds, is only about twice as large as the little State of Florida; and its coast is only three times as long. Yet every year there are about twenty-eight hundred ships lost on the shores of that country. About one thousand men and women and poor helpless children lose their lives; and if we had all the money which is lost by these wrecks, we should have nearly twenty millions of dollars to spend every year.

“You would be puzzled,” continued their father, after the astonishment of the children had subsided, “if you could see one of the maps which the English officer makes out every year, showing the wrecks which have occurred. He calls it the ‘Wreck-chart,’ and the law requires him to publish a new one every year; and what do you suppose it is for? It is a guide-book for the pilots and captains of vessels, and for the wreckers and coast-guards and life-boatmen. On this map a little black dot is put down for every wreck, showing precisely on what part of the coast each of the lost vessels came ashore; and a red one to show the location of every life-boat station. You may believe that, when two thousand of these red and black dots are put down on the map, it has a funny look. Now how does that map guide and instruct the pilots and wreckers and others? The black dots point out the most dangerous parts of the coast,—for, of course, it is most dangerous where most vessels are lost,—and, looking at the map, the pilot and captain know what parts to avoid. It also tells the wreckers and life-boatmen and coast-guard that these dangerous points are where they ought to gather in the greatest numbers to save life and property. That is the use of the English ‘Wreck-chart.’ We do not have any in this country, though we are very much in need of one every year.”

“But, papa,” asked Minnie, “what causes all these wrecks?”

“Why, the wind, Minnie, of course,” spoke up Willie, who, like many another elder brother, had a bad habit of displaying to his younger sister the superior knowledge which he possessed. “Why, the wind and storms,”—he continued, and, seeing his father smiling, Willie tried to think of other causes, and added, “and great rocks in the ocean,—and such things as that!”

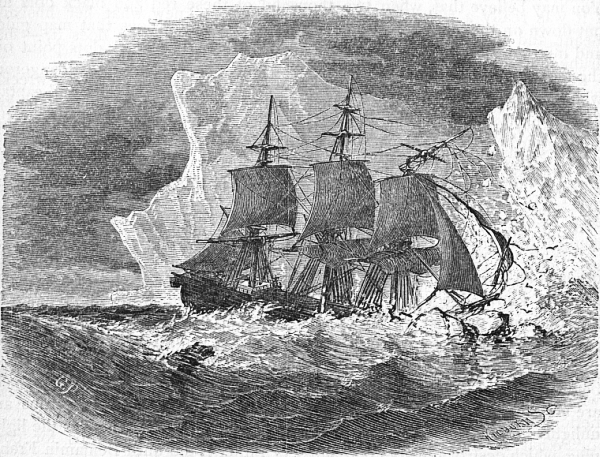

“I am afraid, Willie,” said his father, “that you want to be a teacher before you have finished going to school. The natural causes of shipwrecks are very many more than those you have named. Besides dangerous and unlighted coasts, shifting sands, sudden squalls and storms, there is the lightning, which destroys many good ships, or rather it did until Benjamin Franklin taught us how to control and direct it, and Sir Henry Snow invented his lightning conductor for ships. You would not understand this instrument if I should describe it, but it is said, that, since it has been introduced into the British navy, not a single vessel has been lost by lightning. Then for the destruction of vessels there are the hurricanes and earthquakes which so often occur in the torrid zone, and the great icebergs of the frigid zone. In one day of the year 1857, fifty-eight vessels were destroyed in one little harbor in the West Indies, by one of these hurricanes; and in the same year a great United States ship-of-war named the Monongahela was lifted out of the sea by a wave thirty feet high, and carried nearly over the town of St. Croix. The ship at one time was directly over the market-house! Then the wave receded, and the ship was carried back over the market-house and the town, nearly to the sea, and landed high and dry on a coral reef. Later still, as you may remember, the great iron-clad ship Wateree, the first iron war-vessel built by our government, was carried, by a wave which followed the great earthquake in Peru, half a mile inland and completely wrecked. During the year 1867, more than sixty other vessels were crushed to pieces by the ice in the White Sea. The great icebergs crushed the ships as if they were egg-shells, and the ice was packed around them to the depth of twenty feet, until nothing was to be seen but the masts.

“The icebergs which the sailors call the ‘Phantoms of the Sea,’ and which float down from the Arctic into the Atlantic Ocean, used to cause a great many wrecks, but mariners have learned how to ‘understand their ways’ and know how to avoid them.”

“How, papa, how?”

“I will tell you, but you must listen attentively, for it is not easy to understand. First of all, what do you say is the longest river in the world?”

“The Mississippi,” answered Willie and Minnie in a breath.

“And which is the widest?”

“The Amazon.”