* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Our Young Folks, Volume 5, Number 1

Date of first publication: 1869

Author: J. T. Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom

Date first posted: Nov. 5, 2015

Date last updated: Nov. 5, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20151103

This ebook was produced by: Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

AN

ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE

FOR

BOYS AND GIRLS.

EDITED BY

J. T. Trowbridge and Lucy Larcom.

VOL V.

BOSTON:

FIELDS, OSGOOD, & CO.,

124 Tremont Street.

1869.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by

FIELDS, OSGOOD, & CO.,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

University Press: Welch, Bigelow, & Co.,

Cambridge.

| Page | ||

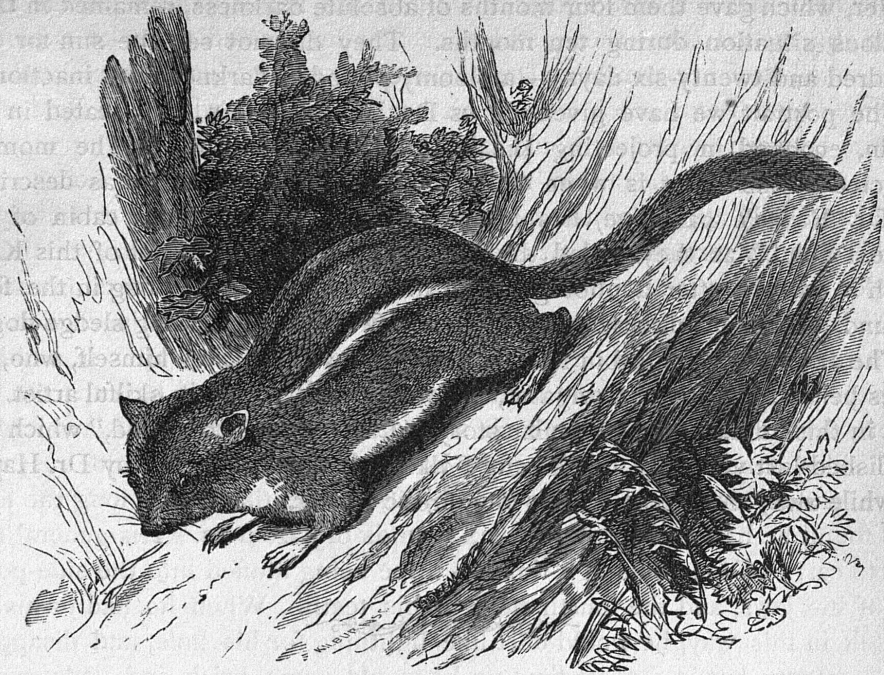

| About Humming-Birds | T. M. Brewer | 578 |

| After Pickerel | Gaston Fay | 396 |

| Among the Glass-Makers | J. T. Trowbridge | 26, 77 |

| Apostle of Lake Superior, The | J. H. A. Bone | 605 |

| Beautiful Gate, The | Helen Wall Pierson | 52 |

| Canary Islands and Canary Birds | James Parton | 309 |

| Candy-Making | Mrs. Jane G. Austin | 302, 388 |

| Carl | Lily Nelson | 296 |

| Carl’s Christmas Carol | M. W. McLain | 807 |

| Cat’s Diary, The | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 88 |

| Chased by a Pirate | David A. Wasson | 747 |

| Day on Carysfort Reef, A | Elizabeth C. Agassiz | 536 |

| December Charade (Farewell) | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 843 |

| Discovery of the Madeira Islands | James Parton | 583 |

| Diverting History of Little Whiskey, The | Harriet Beecher Stowe | 58 |

| Doctor Isaac I. Hayes | 57 | |

| Dr. Trotty | E. Stuart Phelps | 327 |

| Doll’s Regatta, The | Aunt Fanny | 772 |

| Dream of the Little Boy who would not eat his Crusts | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 628 |

| Dunie and the Ice | Sophie May | 99 |

| Excitement at Kettleville, The: A Dialogue | Epes Sargent | 261 |

| Few Words about the Crow, A | T. M. B. | 412 |

| First New England Thanksgiving, The | J. H. A. Bone | 722 |

| Gardening for Girls | Author of “Six Hundred Dollars a Year” | 235, 318, 368, 481, 554, 592 |

| Ghosts of the Mines, The | Major Traverse | 657 |

| Glass Cutting and Ornamenting | J. T. Trowbridge | 147 |

| Going up in a Balloon | Junius Henri Browne | 521 |

| Golden-Rod and Asters | Author of “Seven Little Sisters” | 703 |

| Great Pilgrimage, The | J. H. A. Bone | 669 |

| Hannibal at the Altar | Elijah Kellogg | 188 |

| Hot Buckwheat Cakes | H. L. Palmer | 798 |

| How a Ship is modelled and launched | J. T. Trowbridge | 833 |

| How Battles are fought | Major Traverse | 813 |

| How Ships are built | J. T. Trowbridge | 760 |

| How Spotty was tried for her Life | Ella Williams | 681 |

| How to do it | Edward Everett Hale | 190, 253, 459, 544, 664, 790 |

| In the Happy Valley | Author of “John Halifax, Gentleman” | 444 |

| Kitty; A Fairy Tale of Nowadays | Aunt Fanny | 45 |

| Last Voyage of Réné Ménard | J. H. A. Bone | 400 |

| Lawrence among the Coal-Mines | J. T. Trowbridge | 509 |

| Lawrence among the Iron-Men | J. T. Trowbridge | 617 |

| Lawrence at a Coal-Shaft | J. T. Trowbridge | 357 |

| Lawrence in a Coal-Mine | J. T. Trowbridge | 434 |

| Lawrence’s Journey | J. T. Trowbridge | 289 |

| Le Bœuf Gras | Author of “John Halifax, Gentleman” | 825 |

| Little Barbara | Georgiana M. Craik | 731 |

| Little Esther | G. Howard | 157 |

| Lost at Sea | Georgiana M. Craik | 602 |

| Lost Children, The: A Juvenile Play in Five Acts | Caroline H. Jervey | 112 |

| Navigation and Discovery before Columbus | James Parton | 104, 450 |

| Sixty-Two Little Tadpoles | Author of “Seven Little Sisters” | 336 |

| Spray Sprite, The | Celia Thaxter | 377 |

| Story of a Bad Boy, The | Thomas Bailey Aldrich | 1, 65, 137, 205, 273, 345, 425, 497, 569, 641, 713, 785 |

| Story of the Golden Christmas-Tree, The | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 12 |

| Strange Dish of Fruits, A | Major Traverse | 529 |

| Swan Story, The | Helen C. Weeks | 653 |

| Terrible Cape Bojador, The | James Parton | 739 |

| Violets, The | Annie Moore | 243 |

| Water-Lilies | Author of “Seven Little Sisters” | 479 |

| White Giant, The | Elsie Teller | 184 |

| Who first used the Mariner’s Compass | James Parton | 176 |

| William Henry Letters, The | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 167, 249, 282, 469, 687 |

| World we live on, The | Elizabeth C. Agassiz | 38, 162, 217, 382, 694, 751 |

| Wrecks and Wreckers | Major Traverse | 226 |

Poetry.

| At Croquet | L. G. W. | 583 |

| At Queen Maude’s Banquet | Lucy Larcom | 260 |

| Autumn Days | Marian Douglas | 705 |

| Berrying Song | Lucy Larcom | 563 |

| Bird’s Good-Night Song to the Flowers, The | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 98 |

| Bobolink and Canary | Mrs. A. M. Wells | 410 |

| Christmas-Tide | A. W. Bellaw | 796 |

| Cinderella | Mrs. A. M. Wells | 332 |

| Going to Sleep | Mary N. Prescott | 520 |

| Honor’s Dream | Harriet Prescott Spofford | 42 |

| In the Cottage | Lily Nelson | 477 |

| Johnny Tearful | George Cooper | 832 |

| Lady Moon | Lord Houghton | 491 |

| Lilies of the Valley | Mary B. C. Slade | 288 |

| Little Culprit, The | Kate Putnam Osgood | 183 |

| Little Nannie | Lucy Larcom | 338 |

| Little Sweet-Pea | R. S. P. | 615 |

| Lost Willie | C. A. Barry | 103 |

| Morning-Glory | H. H. | |

| Morning Sunbeam, A | A. Q. G. | 197 |

| Mud Pies | George Cooper | 750 |

| My Heroine: A True Story | Author of “John Halifax, Gentleman” | 10 |

| Red Riding-Hood | Lucy Larcom | 127 |

| Rivulet, The | Lucy Larcom | 418 |

| Sissy’s Ride in the Moon | Annette Bishop | 730 |

| Summer’s Done | Lily Nelson | 652 |

| Swing Away | Lucy Larcom | 633 |

| Taken at his Word | R. S. P. | 759 |

| Three in a Bed | George Cooper | 146, 706 |

| Tom Twist | William Allen Butler | 244 |

| Under the Palm-Trees | Julia C. R. Dorr | 367 |

| Unsociable Colt, The | Edgar Fawcett | 450 |

| Utopia | Edward Wiebé | 128 |

| What will become of me? | Marian Douglas | 224 |

| Why? | L. G. W. | 663 |

Music.

| Berrying Song | F. Boott | 563 |

| Come with me | 126 | |

| Home: Trio | 119 | |

| Lady Moon | F. Boott | 491 |

| Little Nannie | F. Boott | 338 |

| Rivulet, The | F. Boott | 418 |

| Swing Away | F. Boott | 633 |

| Three in a Bed | F. Boott | 706 |

| Utopia | German Air | 128 |

| Round the Evening Lamp | 61, 130, 198, 267, 340, 419, 493, 565, 635, 708, 779, 850 |

| Our Letter Box | 63, 133, 201, 269, 342, 423, 495, 567, 639, 710, 782, 853 |

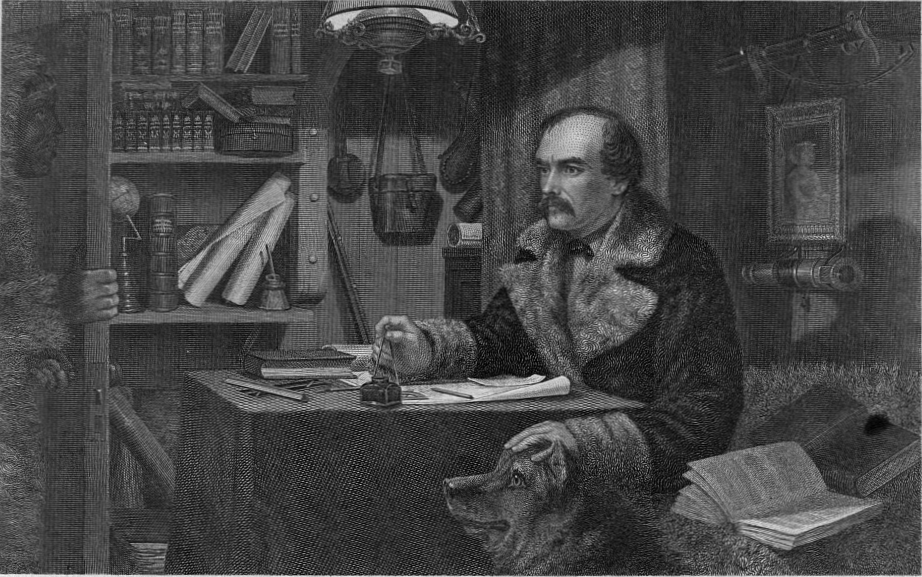

DR. ISAAC I. HAYES.

IN THE CABIN OF HIS VESSEL, IN THE ARCTIC REGIONS.

OUR YOUNG FOLKS.

An Illustrated Magazine

FOR BOYS AND GIRLS.

| Vol. V. | JANUARY, 1869. | No. I. |

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by Fields, Osgood, & Co., in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

[This table of contents is added for convenience.—Transcriber.]

THE STORY OF THE GOLDEN CHRISTMAS-TREE

KITTY; A FAIRY TALE OF NOWADAYS

THE DIVERTING HISTORY OF LITTLE WHISKEY

This is the story of a bad boy. Well, not such a very bad, but a pretty bad boy; and I ought to know, for I am, or rather I was, that boy myself.

Lest the title should mislead the reader, I hasten to assure him here that I have no dark confessions to make. I call my story the story of a bad boy, partly to distinguish myself from those faultless young gentlemen who generally figure in narratives of this kind, and partly because I really was not a cherub. I may truthfully say I was an amiable, impulsive lad, blessed with fine digestive powers, and no hypocrite. I didn’t want to be an angel and with the angels stand; I didn’t think the missionary tracts presented to me by the Rev. Wibird Hawkins were half so nice as Robinson Crusoe; and I didn’t send my little pocket-money to the natives of the Feejee Islands, but spent it royally in peppermint-drops and taffy candy. In short, I was a real human boy, such as you may meet anywhere in New England, and no more like the impossible boy in a story-book than a sound orange is like one that has been sucked dry. But let us begin at the beginning.

Whenever a new scholar came to our school, I used to confront him at recess with the following words: “My name’s Tom Bailey; what’s your name?” If the name struck me favorably, I shook hands with the new pupil cordially; but, if it didn’t, I would turn on my heel, for I was particular on this point. Such names as Higgins, Wiggins, and Spriggins were deadly affronts to my ear; while Langdon, Wallace, Blake, and the like, were passwords to my confidence and esteem.

Ah me! some of those dear fellows are rather elderly boys by this time,—lawyers, merchants, sea-captains, soldiers, authors, what not? Phil Adams (a special good name that Adams) is consul at Shanghai, where I picture him to myself with his head closely shaved,—he never had too much hair,—and a long pigtail hanging down behind. He is married, I hear; and I hope he and she that was Miss Wang Wang are very happy together, sitting cross-legged over their diminutive cups of tea in a sky-blue tower hung with bells. It is so I think of him; to me he is henceforth a jewelled mandarin, talking nothing but broken China. Whitcomb is a judge, sedate and wise, with spectacles balanced on the bridge of that remarkable nose which, in former days, was so plentifully sprinkled with freckles that the boys christened him Pepper Whitcomb. Just to think of little Pepper Whitcomb being a judge! What would he do to me now, I wonder, if I were to sing out “Pepper!” some day in court? Fred Langdon is in California, in the native-wine business,—he used to make the best licorice-water I ever tasted! Binny Wallace sleeps in the Old South Burying-Ground; and Jack Harris, too, is dead,—Harris, who commanded us boys, of old, in the famous snow-ball battles of Slatter’s Hill. Was it yesterday I saw him at the head of his regiment on its way to join the shattered Army of the Potomac? Not yesterday, but five years ago. It was at the battle of the Seven Pines. Gallant Jack Harris, that never drew rein until he had dashed into the Rebel battery! So they found him—lying across the enemy’s guns.

How we have parted, and wandered, and married, and died! I wonder what has become of all the boys who went to the Temple Grammar School at Rivermouth when I was a youngster?

“All, all are gone, the old familiar faces!”

It is with no ungentle hand I summon them back, for a moment, from that Past which has closed upon them and upon me. How pleasantly they live again in my memory! Happy, magical Past, in whose fairy atmosphere even Conway, mine ancient foe, stands forth transfigured, with a sort of dreamy glory encircling his bright red hair!

With the old school formula I commence these sketches of my boyhood. My name is Tom Bailey; what is yours, gentle reader? I take for granted it is neither Wiggins nor Spriggins, and that we shall get on famously together in the pages of this magazine, and be capital friends forever.

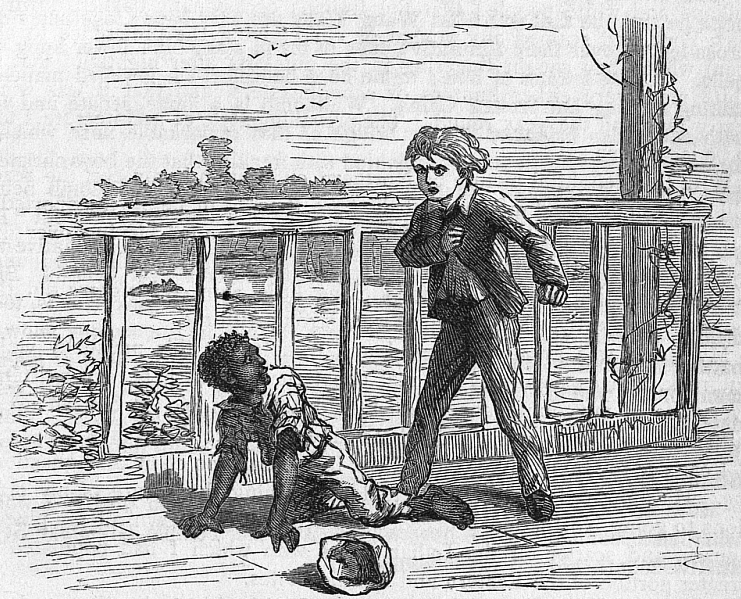

I was born at Rivermouth, but, before I had a chance to become very well acquainted with that pretty New England town, my parents removed to New Orleans, where my father invested his money so securely in the banking business that he was never able to get any of it out again. But of this hereafter. I was only eighteen months old at the time of the removal, and it didn’t make much difference to me where I was, because I was so small; but several years later, when my father proposed to take me North to be educated, I had my own peculiar views on the subject. I instantly kicked over the little negro boy who happened to be standing by me at the moment, and, stamping my foot violently on the floor of the piazza, declared that I would not be taken away to live among a lot of Yankees!

You see I was what is called “a Northern man with Southern principles.” I had no recollection of New England; my earliest memories were connected with the South, with Aunt Chloe, my old negro nurse, and with the great ill-kept garden in the centre of which stood our house,—a white-washed stone house it was, with wide verandas,—shut out from the street by lines of orange and magnolia trees. I knew I was born at the North, but hoped nobody would find it out. I looked upon the misfortune as something so shrouded by time and distance that maybe nobody remembered it. I never told my schoolmates I was a Yankee, because they talked about the Yankees in such a scornful way it made me feel that it was quite a disgrace not to be born in Louisiana, or at least in one of the Border States. And this impression was strengthened by Aunt Chloe, who said, “dar wasn’t no gentl’men in de Norf no way,” and on one occasion terrified me beyond measure by declaring that, “if any of dem mean whites tried to git her away from marster, she was jes’ gwine to knock ’em on de head wid a gourd!”

The way this poor creature’s eyes flashed, and the tragic air with which she struck at an imaginary “mean white,” are among the most vivid things in my memory of those days.

To be frank, my idea of the North was about as accurate as that entertained by the well-educated Englishman of the present day concerning America. I supposed the inhabitants were divided into two classes,—Indians and white people; that the Indians occasionally dashed down on New York, and scalped any woman or child (giving the preference to children) whom they caught lingering in the outskirts after nightfall; that the white men were either hunters or schoolmasters, and that it was winter pretty much all the year round. The prevailing style of architecture I took to be log cabins.

With this delightful picture of Northern civilization in my eye, the reader will easily understand my terror at the bare thought of being transported to Rivermouth to school, and possibly will forgive me for kicking over little black Sam, and otherwise misconducting myself, when my father announced his determination to me. As for kicking little Sam,—I always did that, more or less gently, when anything went wrong with me.

My father was greatly perplexed and troubled by this unusually violent outbreak, and especially by the real consternation which he saw written in every line of my countenance. As little black Sam picked himself up, my father took my hand in his and led me thoughtfully to the library.

I can see him now as he leaned back in the bamboo chair and questioned me. He appeared strangely agitated on learning the nature of my objections to going North, and proceeded at once to knock down all my pine-log houses, and scatter all the Indian tribes with which I had populated the greater portion of the Eastern and Middle States.

“Who on earth, Tom, has filled your brain with such silly stories?” asked my father, wiping the tears from his eyes.

“Aunt Chloe, sir; she told me.”

“And you really thought your grandfather wore a blanket embroidered with beads, and ornamented his leggins with the scalps of his enemies?”

“Well, sir, I didn’t think that exactly.”

“Didn’t think that exactly? Tom, you will be the death of me.”

He hid his face in his handkerchief, and, when he looked up, he seemed to have been suffering acutely. I was deeply moved myself, though I did not clearly understand what I had said or done to cause him to feel so badly. Perhaps I had hurt his feelings by thinking it even possible that Grandfather Nutter was an Indian warrior.

My father devoted that evening and several subsequent evenings to giving me a clear and succinct account of New England; its early struggles, its progress, and its present condition,—faint and confused glimmerings of all which I had obtained at school, where history had never been a favorite pursuit of mine.

I was no longer unwilling to go North; on the contrary, the proposed journey to a new world full of wonders kept me awake nights. I promised myself all sorts of fun and adventures, though I was not entirely at rest in my mind touching the savages, and secretly resolved to go on board the ship—the journey was to be made by sea—with a certain little brass pistol in my trousers-pocket, in case of any difficulty with the tribes when we landed at Boston.

I couldn’t get the Indian out of my head. Only a short time previously the Cherokees—or was it the Camanches?—had been removed from their hunting-grounds in Arkansas; and in the wilds of the southwest the red men were still a source of terror to the border settlers. “Trouble with the Indians” was the staple news from Florida published in the New Orleans papers. We were constantly hearing of travellers being attacked and murdered in the interior of that State. If these things were done in Florida, why not in Massachusetts?

Yet long before the sailing day arrived I was eager to be off. My impatience was increased by the fact that my father had purchased for me a fine little Mustang pony, and shipped it to Rivermouth a fortnight previous to the date set for our own departure,—for both my parents were to accompany me. This pony (which nearly kicked me out of bed one night in a dream), and my father’s promise that he and my mother would come to Rivermouth every other summer, completely resigned me to the situation. The pony’s name was Gitana, which is the Spanish for gypsy; so I always called her—she was a lady pony—Gypsy.

At length the time came to leave the vine-covered mansion among the orange-trees, to say good by to little black Sam (I am convinced he was heartily glad to get rid of me), and to part with simple Aunt Chloe, who, in the confusion of her grief, kissed an eyelash into my eye, and then buried her face in the bright bandanna turban which she had mounted that morning in honor of our departure.

I fancy them standing by the open garden gate; the tears are rolling down Aunt Chloe’s cheeks; Sam’s six front teeth are glistening like pearls; I wave my hand to him manfully, then I call out “good by” in a muffled voice to Aunt Chloe; they and the old home fade away. I am never to see them again!

I do not remember much about the voyage to Boston, for after the first few hours at sea I was dreadfully unwell.

The name of our ship was the “A No. 1, fast-sailing packet Typhoon.” I learned afterwards that she sailed fast only in the newspaper advertisements. My father owned one quarter of the Typhoon, and that is why we happened to go in her. I tried to guess which quarter of the ship he owned, and finally concluded it must be the hind quarter,—the cabin, in which we had the cosiest of state-rooms, with one round window in the roof and two shelves or boxes nailed up against the wall to sleep in.

There was a good deal of confusion on deck while we were getting under way. The captain shouted orders (to which nobody seemed to pay any attention) through a battered tin trumpet, and grew so red in the face that he reminded me of a scooped-out pumpkin with a lighted candle inside. He swore right and left at the sailors without the slightest regard for their feelings. They didn’t mind it a bit, however, but went on singing,—

“Heave ho!

With the rum below.

And hurrah for the Spanish Main O!”

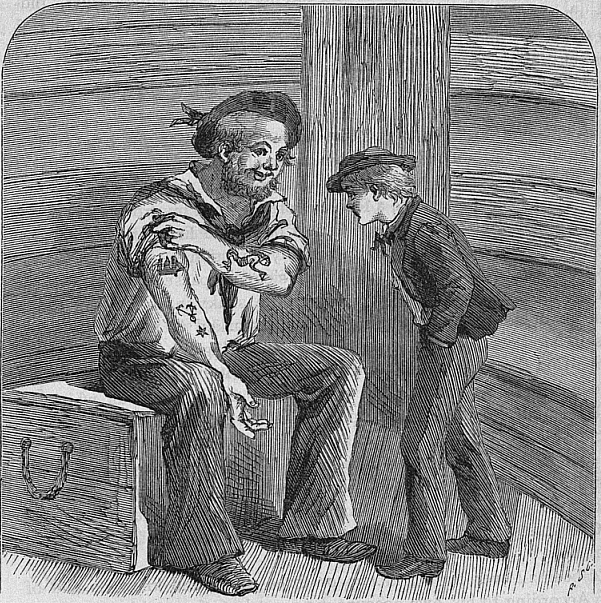

I will not be positive about “the Spanish Main,” but it was hurrah for something O. I considered them very jolly fellows, and so indeed they were. One weather-beaten tar in particular struck my fancy,—a thick-set jovial man, about fifty years of age, with twinkling blue eyes and a fringe of gray hair circling his head like a crown. As he took off his tarpaulin I observed that the top of his head was quite smooth and flat, as if somebody had sat down on him when he was very young.

There was something noticeably hearty in this man’s bronzed face, a heartiness that seemed to extend to his loosely knotted neckerchief. But what completely won my good-will was a picture of enviable loveliness painted on his left arm. It was the head of a woman with the body of a fish. Her flowing hair was of livid green, and she held a pink comb in one hand. I never saw anything so beautiful. I determined to know that man. I think I would have given my brass pistol to have had such a picture painted on my arm.

While I stood admiring this work of art, a fat, wheezy steam-tug, with the word AJAX in staring black letters on the paddle-box, came puffing up alongside the Typhoon. It was ridiculously small and conceited, compared with our stately ship. I speculated as to what it was going to do. In a few minutes we were lashed to the little monster, which gave a snort and a shriek, and commenced backing us out from the levee (wharf) with the greatest ease.

I once saw an ant running away with a piece of cheese eight or ten times larger than itself. I could not help thinking of it, when I found the chubby, smoky-nosed tug-boat towing the Typhoon out into the Mississippi River.

In the middle of the stream we swung round, the current caught us, and away we flew like a great winged bird. Only it didn’t seem as if we were moving. The shore, with the countless steamboats, the tangled rigging of the ships, and the long lines of warehouses, appeared to be gliding away from us.

It was grand sport to stand on the quarter-deck and watch all this. Before long there was nothing to be seen on either side but stretches of low swampy land, covered with stunted cypress-trees, from which drooped delicate streamers of Spanish moss,—a fine place for alligators and congo snakes. Here and there we passed a yellow sand-bar, and here and there a snag lifted its nose out of the water like a shark.

“This is your last chance to see the city, Tom,” said my father, as we swept round a bend of the river.

I turned and looked. New Orleans was just a colorless mass of something in the sunset, and the dome of the St. Charles Hotel, upon which the sun shimmered for a moment, was no bigger than the top of old Aunt Chloe’s thimble.

What do I remember next? the gray sky and the fretful blue waters of the Gulf. The steam-tug had long since let slip her hawsers, and gone panting away with a derisive scream, as much as to say, “I’ve done my duty, now look out for yourself, old Typhoon!”

The ship seemed quite proud of being left to take care of itself, and, with its huge white sails bulged out, strutted off like a vain turkey. I had been standing by my father near the wheel-house all this while, observing things with that nicety of perception which belongs only to children; but now the dew began falling, and we went below to have supper.

The fresh fruit and milk, and the slices of cold chicken, looked very nice; yet somehow I had no appetite. There was a general smell of tar about everything. Then the ship gave sudden lurches that made it a matter of uncertainty whether one was going to put his fork to his mouth or into his eye. The tumblers and wineglasses, stuck in a rack over the table, kept clinking and clinking; and the cabin lamp, suspended by four gilt chains from the ceiling, swayed to and fro crazily. Now the floor seemed to rise, and now it seemed to sink under one’s feet like a feather-bed.

There were not more than a dozen passengers on board, including ourselves; and all of these, excepting a bald-headed old gentleman,—a retired sea-captain,—disappeared into their state-rooms at an early hour of the evening.

After supper was cleared away, my father and the elderly gentleman, whose name was Captain Truck, played at checkers; and I amused myself for a while by watching the trouble they had in keeping the men in the proper places. Just at the most exciting point of the game, the ship would careen, and down would go the white checkers pell-mell among the black. Then my father laughed, but Captain Truck would grow very angry, and vow that he would have won the game in a move or two more, if the confounded old chicken-coop—that’s what he called the ship—hadn’t lurched.

“I—I think I will go to bed now, please,” I said, laying my hand on my father’s knee, and feeling exceedingly queer.

It was high time, for the Typhoon was plunging about in the most alarming fashion. I was speedily tucked away in the upper berth, where I felt a trifle more easy at first. My clothes were placed on a narrow shelf at my feet, and it was a great comfort to me to know that my pistol was so handy, for I made no doubt we should fall in with Pirates before many hours. This is the last thing I remember with any distinctness. At midnight, as I was afterwards told, we were struck by a gale which never left us until we came in sight of the Massachusetts coast.

For days and days I had no sensible idea of what was going on around me. That we were being hurled somewhere upside-down, and that I didn’t like it, was about all I knew. I have, indeed, a vague impression that my father used to climb up to the berth and call me his “Ancient Mariner,” bidding me cheer up. But the Ancient Mariner was far from cheering up, if I recollect rightly; and I don’t believe that venerable navigator would have cared much if it had been announced to him, through a speaking-trumpet, that “a low, black, suspicious craft, with raking masts, was rapidly bearing down upon us!”

In fact, one morning, I thought that such was the case, for bang! went the big cannon I had noticed in the bow of the ship when we came on board, and which had suggested to me the idea about pirates. Bang! went the gun again in a few seconds. I made a feeble effort to get at my trousers-pocket! But the Typhoon was only saluting Cape Cod,—the first land sighted by vessels approaching the coast from a southerly direction.

The vessel had ceased to roll, and my sea-sickness passed away as rapidly as it came. I was all right now, “only a little shaky in my timbers and a little blue about the gills,” as Captain Truck remarked to my mother, who, like myself, had been confined to the state-room during the passage.

At Cape Cod the wind parted company with us without saying so much as “Excuse me”; so we were nearly two days in making the run which in favorable weather is usually accomplished in seven hours. That’s what the pilot said.

I was able to go about the ship now, and I lost no time in cultivating the acquaintance of the sailor with the green-haired lady on his arm. I found him in the forecastle,—a sort of cellar in the front part of the vessel. He was an agreeable sailor, as I had expected, and we became the best of friends in five minutes.

He had been all over the world two or three times, and knew no end of stories. According to his own account, he must have been shipwrecked at least twice a year ever since his birth. He had served under Decatur when that gallant officer peppered the Algerines and made them promise not to sell their prisoners of war into slavery; he had worked a gun at the bombardment of Vera Cruz in the Mexican War, and he had been on Alexander Selkirk’s island more than once. There were very few things he hadn’t done in a seafaring way.

“I suppose, sir,” I remarked, “that your name isn’t Typhoon?”

“Why, Lord love ye, lad, my name’s Benjamin Watson, of Nantucket. But I’m a true-blue Typhooner,” he added, which increased my respect for him; I don’t know why, and I didn’t know then whether Typhoon was the name of a vegetable or a profession.

Not wishing to be outdone in frankness, I disclosed to him that my name was Tom Bailey, upon which he said he was very glad to hear it.

When we got more intimate, I discovered that Sailor Ben, as he wished me to call him, was a perfect walking picture-book. He had two anchors, a star, and a frigate in full sail on his right arm; a pair of lovely blue hands clasped on his breast, and I’ve no doubt that other parts of his body were illustrated in the same agreeable manner. I imagine he was fond of drawings, and took this means of gratifying his artistic taste. It was certainly very ingenious and convenient. A portfolio might be misplaced, or dropped overboard; but Sailor Ben had his pictures wherever he went, just as that eminent person in the poem—

“With rings on her fingers and bells on her toes”—

was accompanied by music on all occasions.

The two hands on his breast, he informed me, constituted a tribute to the memory of a dead messmate from whom he had parted years ago,—and surely a more touching tribute was never engraved on a tombstone. This caused me to think of my parting with old Aunt Chloe, and I told him I should take it as a great favor indeed if he would paint a pink hand and a black hand on my chest. He said the colors were pricked into the skin with needles, and that the operation was somewhat painful. I assured him, in an off-hand manner, that I didn’t mind pain, and begged him to set to work at once.

The simple-hearted fellow, who was probably not a little vain of his skill, took me into the forecastle, and was on the point of complying with my request, when my father happened to look down the gangway,—a circumstance that rather interfered with the decorative art.

I didn’t have another opportunity of conferring alone with Sailor Ben, for the next morning, bright and early, we came in sight of the cupola of the Boston State House.

T. B. Aldrich.

I knew a little maid,—as sweet

As any seven years’ child you’ll meet

In mansion grand or village street,

However charming they be:

She’ll never know of this my verse

When I her simple tale rehearse;—

A cottage girl, made baby-nurse

Unto another baby.

Till then how constant she at school!

Her tiny hands of work how full!

And never careless, never dull,

As little scholars may be.

Her absence questioned, with cheek red

And gentle lifting of the head,

“Ma’am, I could not be spared,” she said;

“I had to mind my baby.”

Her baby; oft along the lane

She’d carry it with such sweet pain

On summer holidays,—full fain

To let both work and play be:

But, at the school hour told to start,

She’d turn with sad divided heart

’Twixt scholar’s wish and mother’s part,

“I cannot leave my baby!”

One day at school came rumors dire,—

“Lizzie has fallen in the fire!”

And off in haste I went to inquire,

With anxious fear o’erflowing:

For yester-afternoon at prayer

My little Lizzie’s face did wear

The look—how comes it, whence, or where?—

Of children who are—going.

And almost as if bound for flight

To say new prayers in angels’ sight,

Poor Lizzie lay,—so wan, so white,

So sadly idle seeming:

Her active hands now helpless bound,

Her wild eyes wandering vaguely round,

As up she started at each sound,

Or slept, and moaned in dreaming.

Her mother gave the piteous tale:

“How that child’s courage did not fail,

Or else poor baby—” She stopped, pale,

And shed tears without number;

Then told how at the fireside warm,

Lizzie, with baby on her arm,

Slipped—threw him from her—safe from harm,

Then fell—Here in her slumber

Lizzie shrieked, “Take him!” and uptossed

Her poor burnt hands, and seemed half lost,

Until a smile her features crossed

As sweet as angels’ may be.

“Yes, ma’am,” she said in feeble tone,

“I’m ill, I know,”—she hushed a moan,—

“But”—here her look a queen might own—

“But, ma’am, I saved my baby!”

Author of “John Halifax, Gentleman.”

“Now,” said Katie,—“now that the grown-up people are away, we children may hope for a little quiet. All sit along in a row, and I will tell you the Story of the Golden Christmas-Tree, that happened long time ago. It begins with two old folks, and they were poor, and lived in a house that had but one door. Now don’t make faces. I mean one outside door. If any of you talk or giggle, or snap knuckles, or roll up your eyes, or pull hair, or pinch, or tickle, I shall stop telling. But chewing gum is no matter.

“And they had a daughter who was a beauty. Just as white as wax-work, and had golden hair, and was quite tall, but not very tall. Her eyes were as blue as a wax doll’s, and her lips as red, and she was slim and slender, with a sweet little foot that stepped light as a feather.

“And they had one more child, but he was a boy, and his name was Valentine; but not a pretty boy,—a homely boy, and his place was always in the back corner. For they loved their daughter best, and sold all their eggs and geese feathers to buy ear-rings for her ears, and necklaces for her neck, and silver rings for her fingers, and ribbons to tie in her golden hair. But the boy had to wear very old things.

“And for the girl it was ‘O sweet angel!’ ‘O my lovely one!’ ‘O pretty darling!’ with kisses for her cheeks and for her lily-white hands. But for him it was ‘O you stupid!’ ‘You naughty one!’ ‘You never do right!’ And while she leaned against the wall, like a picture, with her pretty hands folded, and a fine dress, he scrubbed the floor, and washed the platters, with his old clothes, and the tears in his eyes.

“For he very often wept because nobody cared for him, and longed for some one to come and take him by the hand, and say something kind. And one evening, when he was lying all alone there, he dreamed that the hut was suddenly filled with a bright light, and that a beautiful lady, all in white, bent over him and said very kind words. But the dream passed away, and when he awoke the hut was dark, and he all alone in the cold,—all but his dog, his good old shaggy dog, Fido. Valentine loved Fido, and used to lay his head on the dog’s neck and tell him all his troubles; and Fido would look up so sorryful, and lick his master’s face, just as if he knew.

“There was nobody else for the boy to tell his troubles to, unless it was the one that gave him the dog, Jolly Tom; and he was no relation, not the least, but only skipper of a little sloop. And Valentine used to watch for his white sails, coming over the sea. For Jolly Tom always went whistling along, and often would call out, ‘Ha, Valentine!’ ‘How are you, Valentine?’ in a merry way, and once brought him home quite a large jews-harp, and taught him to play a tune. And the name of the tune was ‘Whistling Winds.’ And when Valentine felt very sad, he would go to his back corner, or away under a tree, and play up a tune, while Fido would sit by and wag his tail to the music.

“But one night a wicked pedler stole the dog away, which made Valentine feel so badly that it seemed as if he could not work at all, but only think of Fido and mourn for Fido all day long.

“This made the two old folks angry, and more cross to him than ever before. And one night they scolded him, and said, ‘O, if you would but keep out of our sight! Away with you!’

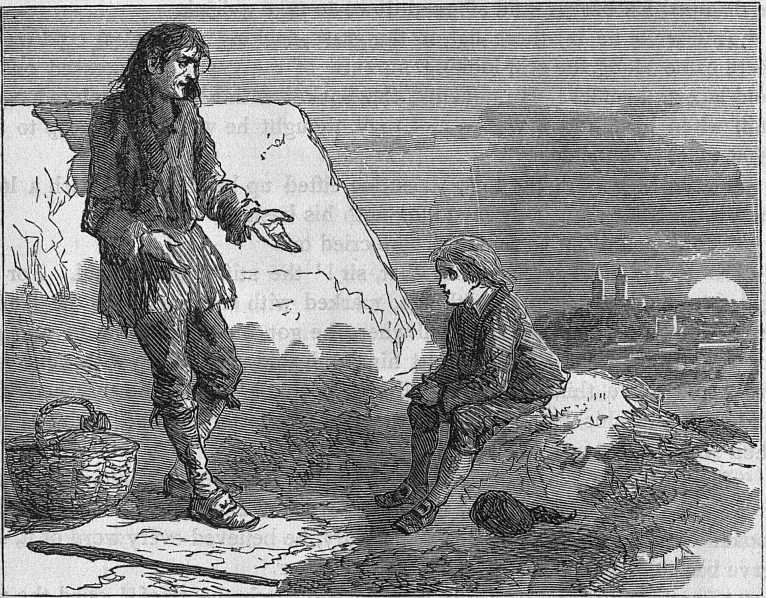

“Then the boy walked a long way off to the sea-shore, where the sea was moaning; and there he lay down on the sands, and listened to the moan of the sea. Darkness was coming on, and it was a very gloomy night. Clouds covered up the stars, and there was quite a chilly blast blowing. Off the shore, near by, were vessels at anchor. He could hear the flapping of the sails and the shouts of the men.

“Pretty soon some sailors, hurrying along, stumbled over him, and one said, ‘Pray, what’s this thing?’

“ ‘O, some land-lubber!’ cried another.

“Then he spoke out and said, ‘I am Valentine. Do you belong to one of the ships? Shall you soon set sail? Is the Captain among you?’

“Then a tall man stepped forward and said, ‘I am the Captain, what do you wish?’

“Valentine asked him if he would like to hire a boy, for he wished to go to seek his fortune in a strange land.

“ ‘Yes,’ said the Captain, ‘I want a good stout boy. Come with us to the boat.’

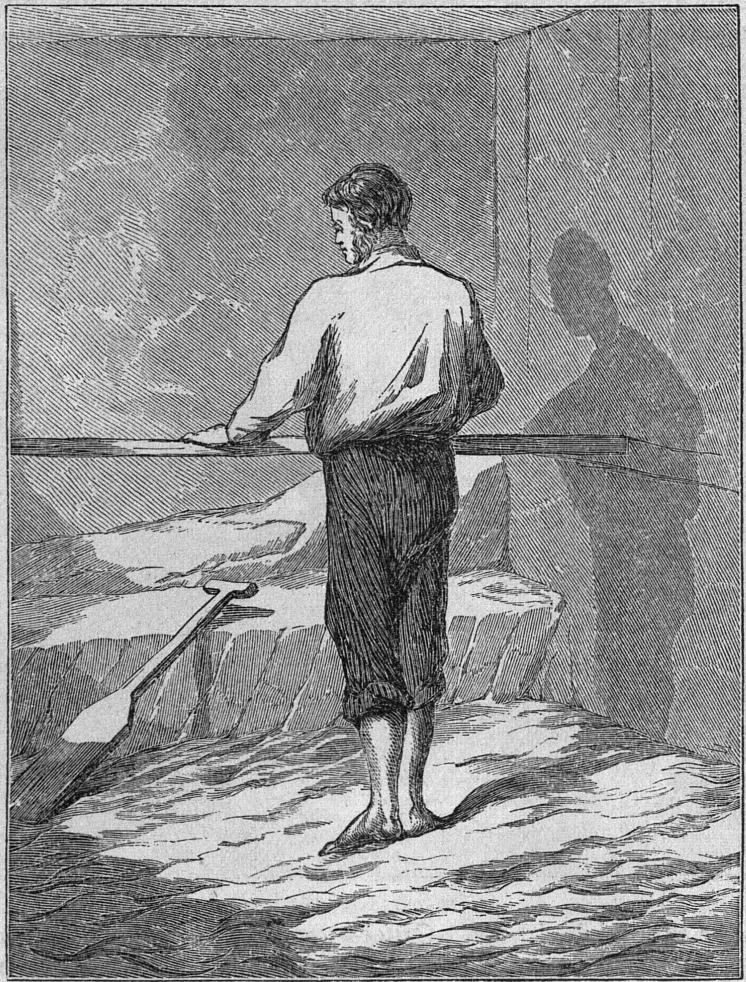

“And when it was seen that he could handle an oar, they allowed him to be one of the rowers to row to the ship.

“And the ship sailed and sailed more than a thousand miles, and anchored at last before a great city.

“Now as Valentine did not wish to be a sailor-boy any more, he said good by to the crew and the captain, and then began walking up and down the streets to find work. It was a very grand city. The buildings were so tall and stately, with many columns and towers and porticos. There were marble statues standing about in very good places, and fountains sparkling, and palm-trees waving, and flowers blooming everywhere. And the people were dressed in very bright-colored clothes.

“Now as Valentine walked up and down, he came to the Palace. And said he, ‘Since all is fine in this grand city, I may as well try my luck here as at any other place.’

“So he went through the back gate, and put his head in at the kitchen door. And as the cooks were far too busy to mind him,—for it was a feast day, and there were over forty lambs to be roasted,—he went through a back passage, and passed from room to room very softly,—walked softly because he was a little afraid, everything was so wonderful, and so bright, and so grand!

“At last he stubbed his toe against a gold nail which stuck up in the floor, and out jumped a man from behind a velvet curtain, twenty feet long!”

“The man, Katie?”

“How silly! Do you want I should stop telling?”

“O no.” “O no!” “No, no, no, no, no!”

“Keep quiet, then, and don’t interrupt. This man that jumped out had three feathers in his cap, and, as Valentine didn’t know his real name, he called him, ‘Mr. Three Feathers.’ He said, ‘Mr. Three Feathers, will you please give me some work to do?’

“Now the man was so angry at being called ‘Mr. Three Feathers,’ that he took Valentine by the collar and began running him out of the Palace.

“But a man that had four feathers called out, ‘What are you doing with that boy? What does he want?’

“ ‘Wants work to do,’ said Mr. Three Feathers.

“ ‘Well,’ said Mr. Four Feathers, ‘why turn him away? Don’t you know that we are wanting a throne boy?’

“So Valentine was hired to be the throne boy, and was arrayed in fine array, as was quite proper for one who dwelt in a palace. It was his business to take care of the ornaments which adorned the throne, and to rub the golden candlesticks, and dust the ivory steps, and beat up the purple cushions. Every morning his hands had to be dipped in perfumed water.

“He did everything as well as he could, and the King was so pleased that he patted his head very often. Every month he got a large gold piece and a new pair of shoes. And he said to the King one day, ‘The shoes I put under my bed, but where shall I put my gold pieces?’

“Then the King gave him an ivory-handled spade, and an apple-tree, in his own private garden, where he might dig a hole underneath to bury his gold pieces. And there he would sit, when work was done, and play on his jews-harp the tune of ‘Whistling Winds,’ and think of Jolly Tom, and of the dog that was stolen away. And he said to himself, that some day he would take all his money home, and build the two old folks a new house. ‘For I am still their son,’ he said, ‘and must take care of them when they are past work.’

“And when Valentine had lived in the Palace a very long time, the King said to him one day, ‘As I find that you are one to be trusted, I shall employ you to go on a long journey. You see this letter. It must be taken to the Great Governor Joriando. He is—But that you will find out for yourself.’

“The letter was very square and large, and sealed together with a great deal of red sealing-wax.

“ ‘Put this letter,’ said the King, ‘inside your inner vest, and button it tight; you see it is marked “Private.” Do you know the way?’

“ ‘I can ask,’ said Valentine.

“But after travelling a long time he came to a sandy desert, where there were no paths, and no one to point out the way. And it happened that he came out on the wrong side of the desert. There he met a soldier clad in armor, with tall, waving plumes; and he asked this soldier, ‘Can you tell me where lives the Great Governor Joriando?’

“ ‘No, I can’t tell you,’ said the soldier; ‘but I have heard of him. He is—’

“Just then a trumpet sounded, and the soldier hurried away. Then Valentine walked the country up and down, asking of all people, ‘Can you tell me where lives the Great Governor Joriando?’ Some turned away, some stroked their faces and smiled, but none could tell.

“At last he grew very weary of wandering about, and one day, as he was passing through a hay-field, he threw himself down to rest against a haycock, but was no sooner down than up jumped a man from the other side, and came round to see who was there. He was quite a pale-looking man, and seemed to be a traveller.”

“Katie, did Valentine leave his gold pieces under the apple-tree?”

“No. I forgot to tell about that. He dug them up, and put them in a leather bag, and hung it about his neck. Now, what was I telling when Dicky asked that question?”

“About the pale man.”

“O yes. He was a pale, sick-looking man, with hollow cheeks and black hair, and carried a basket with the cover tied down.

“ ‘Are you very tired?’ he asked.

“ ‘Yes, very,’ said Valentine. ‘Can you tell me where lives the Great Governor Joriando?’

“No. The traveller had never heard of such a governor. But he sat down by the side of Valentine, and there they talked together in a very friendly way. He was quite a sad man, with a low and sorrowful voice. Valentine took out his jews-harp and played up a tune, but the stranger did not seem pleased at all, but only turned his head away.

“And when they had taken quite a long rest, the traveller said, ‘What do you think? Since you know not where to go, will you go with me?’

“ ‘With all my heart,’ said Valentine.

“And the two travelled together for many days, along highways and by-ways, by the banks of little brooks, and through pleasant woods, where birds sang and the leaves rustled in the breezes.

“And one evening they seated themselves, just as the moon was rising, on the top of a steep hill. There was a very large, high, smooth rock there—a white rock—that they leaned against. This rock was called the ‘White Horse.’

“They stood by this rock and looked down. Below them there lay a large city, which looked beautiful in the moonlight. It was a very calm, still night. On their right hand were piled up the dark mountains, and on their left hand the wide sea was spread out, and many ships were sailing there.

“The traveller stood quiet, with his arms folded, a long time, saying not a word.

“But at last he turned to Valentine, and said, ‘What do you think? I have something to tell. Will you hear it?’

“ ‘Very gladly,’ said Valentine.

“Then the Traveller pointed to a spot just outside the city, and asked, ‘Do you see those turrets which point up so high among the green trees?’

“ ‘Yes,’ said Valentine, ‘I see the turrets.’

“ ‘They belong to a grand old castle,’ said the traveller. ‘And in that castle dwell a noble old couple, who have lived their lives very happily there for more than fifty years.

“ ‘And when the fiftieth year came round, they said, “Let us celebrate our Golden Wedding. And, since it falls on Christmas, we will have for our grandchildren a Golden Christmas-Tree, whereon the presents shall be of pure gold.”

“ ‘And they bought of a countryman a fine green fir-tree, of a lovely shape, and quite tall, because the walls were so high.

“ ‘Very soon came the joyful Christmas Eve, and not an old couple in the kingdom were so happy as they! For all had come to the Golden Wedding. Not even one little grandchild was missing.

“ ‘Ah, but that was a happy sight! The grandmother was dressed in a velvet gown and a feather in her turban, and her fat face was smiling all over! The grandfather had his arms full of little children, and sang, and laughed, and wiped the tears from his eyes,—happy tears. Pretty, fair girls, dressed all in white, danced from room to room, and the gallant youths and the lovely maidens kissed one another under the mistletoe-bough!

“ ‘Are you listening, Valentine?’ the traveller asked.

“ ‘Yes,’ said Valentine, ‘I am listening. Please tell the rest.’

“ ‘I will,’ said the traveller. ‘I have resolved to tell the rest, and I shall tell it.

“ ‘You must know that, in the midst of all the gay time, two of the mothers went away to a distant room, where the Tree had been placed, to light it up and arrange the presents. And O, these were a dazzling sight to behold! There were bracelets, coronets, charms, watches, lockets, clasps, rings, vases, buckles, all made of gold, and long golden chains!

“ ‘And after everything was ready, the two mothers went up to the Grand Banquet Hall, to see that for the Golden Wedding Feast nothing was lacking; and left the Tree, with all its golden fruit, in care of a servant whom they fully trusted. For he had been a long time their servant, and they had been very kind to him, and to his little girl that died.’

“The traveller stopped in this part of his story, and bowed down his head, and did not say more for quite a long while. And when he began again his voice sounded lower and sadder than before.

“ ‘That servant,’ said he,—‘that servant whom they trusted, when he was left alone there, thought to himself, “How many fine clothes all these would buy! How many bottles of wine! How many good things to eat and a coach and horses besides! If I only had them for my own, and was far away from here, then I should be happy!”

“ ‘And now, what do you think? He took all those golden things!

“ ‘And when the doors were thrown open, and the people came in haste to see the Golden Christmas-Tree in all its glory, why, those presents were miles away, among yonder mountains, and the base robber was seeking some place to bury them in!’

“ ‘The wretch! The mean villain!’ Valentine cried out. ‘If I could but get hold of him!’

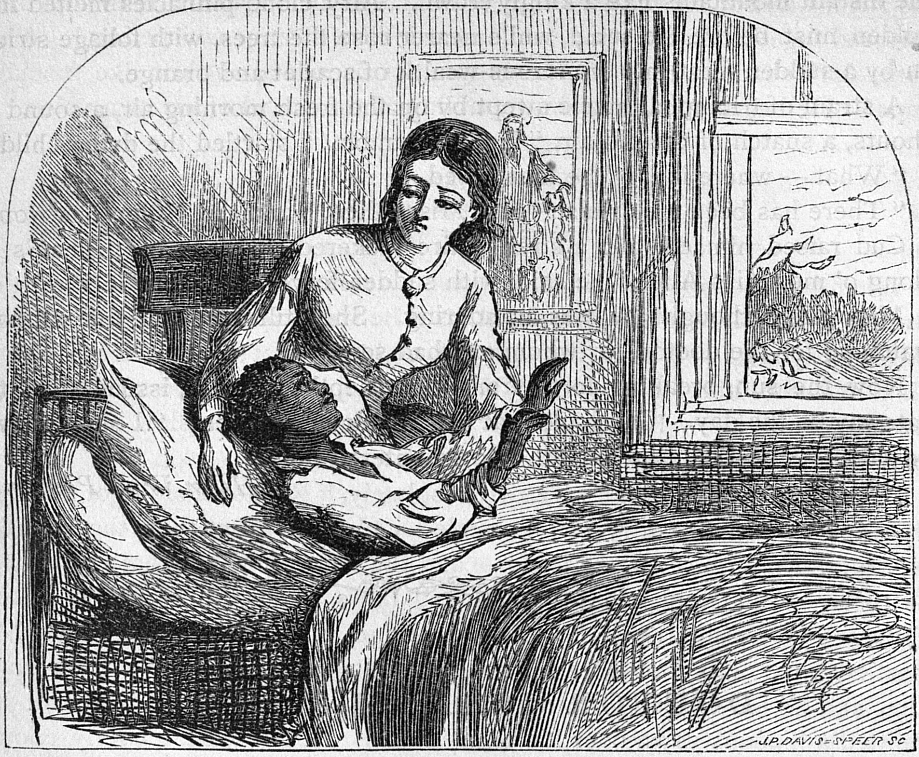

“I HAD TO MIND MY BABY”

Drawn by Miss Patterson.] [See My Heroine, page 10.

“ ‘And if you could,’ then the traveller asked, ‘what would you do with him?’

“ ‘Throttle him!’ cried Valentine. ‘Bind him hand and foot! Tear him limb from limb! Hand him over to the officers! For he was trusted, and he deceived them!’

“ ‘It is a pity,’ said the traveller, ‘that you could not get hold of him!’ ”

“But Katie,” said little Dick, “we don’t get any Golden Christmas-Tree in our story, after all. For the presents were stolen away!”

“Now, Dick,” said Katie, “please be quiet. ‘After all’ hasn’t come yet. Wait till my story’s done, sir. I was going to tell that in this part of his story the traveller folded his arms, and began walking backwards and forwards, and at every turn he came a little nearer Valentine.

“At last he came close up, and stooped over, and whispered, ‘I myself am that wretch, that mean villain!’

“Then he stepped back, and said, ‘Now do as you promised. Throttle me. Bind me hand and foot. Tear me limb from limb. Hand me over to the officers. For they trusted me, and I deceived them!’

“But Valentine started back, thinking about his gold pieces, and put his hand up to where they hung. This made the traveller smile.

“ ‘Don’t be afraid,’ said he. ‘I know you have something of value there, because you raise your hand to it so often. Don’t you know that is the very way to let your secret be known? But I don’t want your gold. I’m sick of gold. I want you to hear the rest of my story, and then do me a favor.’

“He then told Valentine how he buried the golden presents in a low secret valley, and then wandered about among the mountains, and never dared to show his face. At last came a furious snow-storm, and in that he almost died. But a good shepherd carried him to his hut.

“ ‘And when next I could walk about,’ said the traveller, ‘the flowers of spring were blooming. For I was sick a very long time,—too sick to notice anything at all. Yet I did see something, or seemed to see it,—something very strange. Now what do you think? All through that long sickness I saw, or seemed to see,—a Hand! A busy, never-weary Hand, which wrote, wrote, wrote everywhere! The letters it made were the color of bright red coals, and when put together they made the word—“Thief!” Wherever I looked, on the furniture, on the walls, on the ceiling, on the floor, on the bed-clothes, there was the Hand, steadily at work, writing, writing, writing, and always fast, as if not one moment could be lost. It wrote on my flesh. And then the letters burned! O, you may believe that I suffered!

“ ‘Now when I got well, do you suppose I went to that low, secret valley, and dug up those golden things, and sold them? O no, I could not bear to see them. And I stayed there with the shepherd, and helped him watch his flocks by night.

“ ‘And it happened that one day the Queen passed over the mountains with all her train. And she wanted to find a little blue flower, but none of them knew where it grew. Now I had seen some growing far below, on the face of a steep rock, and I let myself down there, and picked a good handful. She liked me very much for doing this, and took me to her own city; and as I pleased her well she gave me first money, next rich presents, and next a fine house, where I made grand parties, and we had music and dancing, and very gay times.

“ ‘But what do you think? The Hand came back! Or seemed to come back. And wrote that same word! Wrote it on the green of the grass, wrote it on the blue of the sky and on the darkness of the night, wrote it on my forehead, and I looked in the looking-glass very often to see if the word showed there. For I thought people could read it. Even in my dreams it was just the same. For then the good Baron himself would seem to stand before me, and hold out a paper, with that word written on it; or else my little girl that died would seem to hold it out to me, and look so mournful!

“ ‘And something else came. A whispering. A low, whispering voice at my ear. Only one word, but it was that same word. I seemed to hear it everywhere. In the streets I heard it, and turned quick to see who was whispering. But no one was there. In the midst of the music and dancing, and in the still hours of the night, I heard it too, and could not sleep. But still I would not take the things and carry them back to the Baron. I shall feel better soon, I said. But I did not feel better.

“ ‘And now what do you think? Shall I tell you what is in this basket? All those golden things are here. One night when I could not sleep I said to myself, I will set off by the early morning light, and I will go to that low, secret valley, and I will dig up those golden presents, and return them to their owner. And from the very moment that I said this to myself I never saw the Hand nor heard the whispering!

“ ‘And now the castle stands before me. But I cannot, O I cannot meet the eye of that old man. Do you know why I have brought you here, and told you this story? To ask you to give these into the Baron’s own hands, and say to him that I will remain until to-morrow night at the “White Horse,” where the officers may find me.’

“Early in the next morning Valentine arrived at the castle, and began walking about the grounds to see what he could see.

“And the first thing he saw was a little spring of water bubbling up, and he dropped his basket, and stepped down to take a drink.

“And while he lay there flat on the grass, sucking in the clear cold water, there came along the stiff-looking steward of the castle, all dressed out in gold lace and ruffles. He touched the basket with his silver-pointed cane, and, when he found it was very heavy, thought he would just peep to see what there was inside.

“Just as he was doing this, Valentine lifted up his head to catch a long breath, and saw somebody meddling with his basket.

“ ‘Don’t meddle with that, sir!’ he cried out.

“ ‘Indeed I shall meddle with that, sir!’ the stiff steward said. For he had found all those golden things, marked with the names of the family. And when Valentine began to tell where he got them, and what he was going to do with them, he laughed at him, and said, ‘Hush up with your silly story! Do you think anybody will believe that?’ Then he searched him, and took away his bag of gold pieces, and the letter marked ‘Private,’ and then shut him up in a cell.

“But when the Baron came home he said, ‘Let me look him in the face! I can tell by his face whether he speaks true or false.’ And when he had looked him in the face, and heard his story, he believed every word of it, and gave back the gold pieces and the square letter.

“ ‘Then send to the “White Horse,” and catch the thief!’ cried the stiff steward.

“But the Baron said, ‘No. That man’s thoughts are the worst punishment he can have.’

“And when he saw that the lad was a smart, likely lad, he offered to employ him; but Valentine said he must go to find the ‘Great Governor Joriando.’

“Then a merchant stepped forward, who had journeyed from a far country, and said that a long time before he had passed the Great Governor Joriando with a troop of soldiers, and that they were marching in haste to the King’s Palace. And also that the King and all his armies were gone to the wars.

“ ‘But keep the letter,’ said the Baron. ‘It may be of use to you.’

“ ‘Yes, keep the letter to the Great Governor Joriando, by all means!’ said the merchant. And he went away.

“So Valentine remained with the Baron, and served him a very long time, and saved a great deal of money.

“And one day as he was sitting all alone in a shady lane, playing on his jews-harp, he looked through the trees and saw a cottage where a lovely girl sat in the doorway, weeping. And he went to find out the reason. The name of this girl was Pauline. She was weeping because the goats had gone astray. For they were her uncle’s goats, and he would be angry with her for their going astray.

“Now Valentine was always ready to do favors; so he ran quickly to find the goats, and drove them home. And the lovely young girl smiled very sweetly through her tears.

“And not long after he walked in the shady lane again, and found the lovely girl sitting in the doorway, weeping for her only brother, who had joined a band of rovers, and gone roving away.

“ ‘Do not weep,’ said Valentine. ‘He will soon come back, and will have many fine tales to tell.’ And then he related to her many things he had seen in his own travels.

“And it happened that every day after this he walked in the shady lane, and every day he saw the lovely girl, and every day she smiled upon him, and they talked pleasantly together.

“But one day Valentine stayed away, and sat down by himself to think. And he thought this: ‘What a pity that I am ill-looking! If it were not so, I would ask Pauline to be my wife. I am very sorry. Yet it must be so, for did they not always say that of me at home? Yet Pauline smiles on me, and Pauline is very lovely. I wonder how it is!’

“The truth was that Valentine had grown up quite tall and manly. His smile was very sweet; and he had a pleasant way which charmed everybody, and charmed Pauline so much, that, when at last Valentine asked, ‘Will you be my wife, and go to dwell with me in my own native country?’ she did not say ‘No,’ but said only, ‘Wait till my brother comes home.’ And then Valentine knew, that, if the brother said ‘yes,’ Pauline would not say ‘no.’ And when the brother came home, he not only said ‘yes,’ but declared that nothing would suit him better than to go too; for that was a part of the world he had never seen.

“O how happy was Valentine then!

“And when Pauline heard about the two old folks, and of the little hut where he was once so sorrowful, she said, ‘Listen, now. I have taken a fancy that our wedding shall be nowhere but in that little hut, where you were once so sad and sorrowful. And after the wedding, we will build a new house for the two old folks and take good care of them; for are you not still their son?’

“ ‘Just as you please,’ said Valentine. And the brother, who was always in haste, began that very hour to buy the wedding clothes.

“Now in the mean time, while Valentine was so far away, the beautiful daughter at home had grown up. And the two old folks said to one another, ‘Now surely some prince will come to marry our beautiful daughter, and will clothe her in royal robes, and place her upon a throne, and we shall sit at her right hand.’

“But the girl was not kind to the two old folks, and was too idle to learn anything, but thought only of her fine looks; and, besides, she was not sweet-tempered, but was quick to get angry. And to the poor beggar women, instead of giving them a kind word or a taste of her bread, she would say, ‘Out of the way with you!’

“And one day a prince came along, and saw this pretty maiden, sitting upon a green bank twining a wreath of flowers. And he said, ‘What a beautiful maiden! I will make her my Princess.’

“But first asked of the neighbors, ‘Is she wise? Is she sweet-tempered?’

“ ‘O no, not at all,’ the neighbors said.

“ ‘Then she’ll not do for me,’ said the Prince. ‘For if she cannot govern her temper she cannot govern people; and to set a dunce upon the throne would be folly. I’ll pass on.’

“The next year a great lord passed by, and saw this pretty maiden, dressed in her finery, all ready for the Ball. And he said, ‘What a beautiful maiden! I will make her my Lady.’

“But first asked of the neighbors, ‘Is she good to her mother?’

“ ‘O no, not at all,’ the neighbors said.

“ ‘Then she will not do for me,’ said the Lord. ‘A girl who is not good to her mother will be good to nobody. I’ll pass on.’

“The next year there came a baron riding by; and he saw this pretty maiden sitting under a tree, stringing beads for a necklace. And he said, ‘O, what a beautiful maiden! I will make her my Baroness.’

“But first asked of the neighbors, ‘Is she kind to the poor?’

“ ‘O no, not at all,’ the neighbors said.

“ ‘Then she will not do for me,’ said the Baron. ‘On my estates are many poor. I’ll pass on.’

“And the next year there came along a merry young farmer, with a round rosy face and wavy locks. And he saw this pretty maiden looking at herself in a clear, still fountain, and braiding her golden hair. Then he watched her through the branches of a green tree, and he said, ‘O, what a beautiful maid! I will make her my wife.’

“But first he asked of the neighbors, ‘Is she industrious?’

“ ‘No, not at all,’ the neighbors said.

“ ‘Then she’ll never do for a farmer’s wife,’ he said; and laughed his merry laugh, and shook his wavy locks, and passed on.

“Thus years slipped away, and the beautiful daughter was left to twine her flowers, and dress, and string her beads, and braid her golden hair by herself, since none cared to marry her. But the older she grew the more disagreeable she became, and caused the two old folks to weep very bitter tears. And this made them remember their long-lost son, who was so patient and so kind.

And one day Jolly Tom came to see if they had any geese feathers to send away; for he was going to a distant country with a company of merchants, to sell wool. Jolly Tom was a wool-dealer now, and lived upon the hill near by, in a fine house of his own.

“And when he came to ask about the geese feathers, there he found the two old folks, sitting in the dim twilight, weeping.

“ ‘What is the matter?’ asked Jolly Tom. ‘And why do you weep?’

“ ‘It is the conduct of our daughter which makes us weep,’ they said; ‘and we are also mourning for our son,—our long-lost son!’

“ ‘Whom we drove away,’ said the father.

“ ‘O, he would not treat us so!’ said the mother. ‘If he would only come back again! He was good to us always. Say, father, did he give us ever one unkind word?’

“ ‘No, dame, no, never. And don’t you remember how ready he was to help?’

“ ‘Ah yes! and so tender-hearted, and so patient!’ said the dame.

“ ‘But we were not kind to him,’ said the father.

“ ‘We broke his heart!’ said the mother. ‘Don’t you remember how sorrowful he looked at us, with the tears in his eyes? O, if he would only come back, how I would throw my old arms around him!’

“ ‘I would fall upon his neck, and weep tears of joy!’ said the father. ‘But O where is he now? Perhaps not alive.’

“ ‘Perhaps drowned in the deep sea,’ said the mother, ‘or buried in some distant land, where strangers walk over his grave, but none cast any flowers there. O how could we drive our child away?’

“ ‘Cheer up, cheer up!’ cried Jolly Tom; ‘I will inquire of all I meet at the Great Fair, where will come merchants from all countries. Who knows but we may get news of him?’

“Now when Jolly Tom returned from the Fair, the two old folks went to ask what news. Alas, there were no tidings of Valentine!

“ ‘But, my good friends,’ said Jolly Tom, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll marry your daughter.’

“ ‘What, marry our daughter!’ cried the two old folks. ‘Don’t; she is vain, and idle, and bad-tempered!’

“ ‘O, I’ll manage all that!’ cried Jolly Tom.

“So they were married. For the pretty daughter wished much to be mistress of a house.

“And whenever Mrs. Jolly Tom got angry or cross, Mr. Jolly Tom would set up a hearty laugh, as loud as he could, and double himself up, and caper, and roll upon the floor, laughing so loud that she was obliged to laugh herself.

“And if Mrs. Jolly Tom sat idle, with folded hands, when there was plenty to do, Mr. Jolly Tom would say, ‘O what a fine wax figure! Pray cover it from the dust! And then he would throw a bit of gauze over her face, or dust her with a feather-duster, as the showmen do; and then set up his laugh, till his wife was glad to go to work.

“And every time that Mrs. Jolly Tom decked herself out in gay gauds, and stood long before the looking-glass, Mr. Jolly Tom presented her with a peacock, so that in a short time the barns and yards were so filled with them that one could scarcely stir for peacocks. But, every day that she behaved well all day, Mr. Jolly Tom allowed one peacock to be killed. And she soon grew so good that very few were left. But he saved the feathers, and hung them over the looking-glass, to make her beware of vanity. And that was the way peacock-feathers began to be hung over looking-glasses.

“Thus it came to pass that this couple lived quite happily.

“And one cold day there came a stranger to the door, and said to Jolly Tom, ‘Sir, I wish to tell you a secret.’

“And Jolly Tom said, ‘Sir, pray be in haste with your secret; for Christmas is near, and we are busy in preparing a Christmas-Tree for our two little boys.’

“Then the stranger took him away into a lonely field, and said, ‘Don’t you know me? Jolly Tom, don’t you know me?’ Then he took out his jews-harp, and played up the tune of ‘Whistling Winds.’

“ ‘Bless me! bless me!’ cried Jolly Tom. ‘You must be our Valentine!’ Then he hugged him, and jumped about, and tumbled down, and picked himself up, laughing away all the time; and at last says he, ‘Well, now, tell me your secret.’

“Then Valentine told him that he wished to do something for the two old folks to surprise them, and begged Jolly Tom to help, and to keep it private. And very soon you shall know what it was.

“On the twenty-fourth day of December, Jolly Tom sent a stout man, with a sled, and plenty of blankets, to invite the two old folks to his house. And the stout man wrapped them up well, and seated them on the sled, and told them to hold fast by the stakes. And for the hand which held the stake was a fur mitten. In this way they were carried to their daughter’s house. She knew all about it, and the little boys knew too.

“Just after dark Jolly Tom came in, and raised the window-curtain, and cried:—

“ ‘Father! mother! look! look out! There’s a bright light in your hut! It looks all ablaze!’ Then he stood behind the door to laugh. But he had to stuff his mitten in his mouth.

“Then everybody ran, and the stout man bundled up the two old folks in their blankets; but this time no one thought of the fur mittens.

“And when they came near the hut, the old man cried out, ‘Do but see what a blaze! All will be lost!’

“ ‘And five silver dollars in the cupboard!’ cried the old dame.

“But Jolly Tom, who stood by, nearly swallowed his pocket-handkerchief to keep himself from laughing.

“Then the stout man burst open the door, and O what a sight! O what a sight! A blaze indeed! And by the light of it what do you think they saw? But first I must tell you where the light came from. In the middle of the room stood a Christmas-Tree, of an elegant shape, blazing with candles, brilliant with gold, and dazzling to behold! For from every little twig hung a bright gold piece! All for the two old folks. A real, golden Christmas-Tree!

“At one end of the room stood a tall, manly youth, with a smiling face, and a bran-new wedding suit. He held by the hand a lovely girl, dressed in pure white, with a long flowing veil. Near by stood the Priest, who was to marry them, in his long black robes. Pauline’s brother was on the other side, dressed in a gay tunic, with buckles on his knees, and a red tasselled cap.

“The two old folks stood in the doorway, and could not speak a word.

“But the tall youth came forward, leading the lovely bride. And they both knelt down before these two old folks, and began kissing their hands.

“ ‘Father, mother, give us your blessing!’ cried the youth. ‘For I am your son, and this dear girl will be your loving daughter!’

“And when they clasped him in their arms, and he felt their warm tears and their kisses, and heard them sob out, ‘Bless you! bless you! our son and our daughter!’ then Valentine bowed down his head, and wept tears of joy!

“And Pauline, when she saw him weeping, bent down, and took his hand, and said loving words to him.

“Then he remembered how one night, when he was a boy, lying there all alone, he dreamed that a bright light filled the hut, and that a beautiful lady, all in white, bent over him, and spoke kindly, and then vanished away, and left him cold and alone.

“And when he remembered this dream he caught Pauline by the hand, and cried out, ‘O, don’t vanish away! don’t vanish away!’

“Then Pauline laughed, and said, ‘My dear, I wouldn’t vanish away for all the world.’

“Then Jolly Tom clapped his hands, and laughed, and capered about, and Mrs. Jolly Tom did the same, and the little Jolly Toms, and threw up their caps. And then Pauline’s brother began, and then the happy couple, and at last the two old folks, and last of all the Priest also; and such a laughing and a clapping and a capering never was known before.

“But at last Valentine said, ‘Sir Priest, will you please to marry us?’

“Then all became quiet, and stood in a circle around the couple; and one little boy peeped out from behind his mother, and the other little boy held his father’s coat-skirts, while the Priest married Pauline and Valentine. And I can tell you that every one kissed the bride!

“And after the wedding supper was eaten, when Jolly Tom began to dance and caper about because he could not keep still, then Valentine sat down in his old back corner, and played up the tune of ‘Whistling Winds,’ while Jolly Tom danced a jig with the bride.

“And after that he went and sat near the two old folks, and told his whole story, while all the people listened. And to prove it he took out the square letter marked ‘Private,’ upon which was written, ‘To the Great Governor Joriando.’

“And years and years after he used to repeat this story to his children, and at the end they would say, ‘Now take out the square letter, father.’

“Then he would take out the letter, quite soiled and yellow, and turn it over, and sigh, and say, ‘One thing troubles me,—that I never saw the “Great Governor Joriando!”’

“But when asked to open the letter, to see what was inside, he would say, ‘Don’t you see it is marked Private?’ ”

Mrs. A. M. Diaz.

“Well, Lawrence,” said the Doctor, one day, shoving his chair back from the dinner-table, “how do you think of spending this afternoon?”

“I think I shall finish this piece of pie the first thing,” said Lawrence. “Then, as I’ve no lessons to learn, I feel as if I should like to have a good time.”

“If you could manage to have what you call a good time, and learn something too, how would that suit you?” Lawrence thought that would suit him better than anything else. “Well,” said the Doctor, “I have business down near the Glass Works; you can go with me, if you like, and perhaps we can learn something about making glass.”

“Hurrah!” said Lawrence, delighted; and his pie went the way of all pie in the hands of boys of fifteen, with more than usual rapidity.

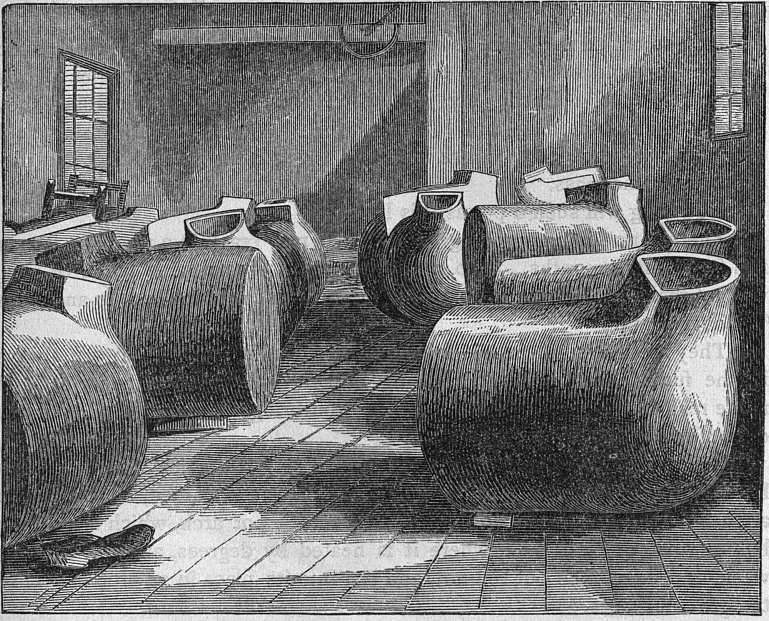

They had just time to walk to the railroad station, and step on board the down train as it stopped. It thundered on again, and in half an hour brought them in sight of a building which the boy knew as the Glass Works, and which he had long wished to peep into. His heart beat quick with curiosity; and he began to wonder (for he had never given the subject much thought before) how such an infinite variety of useful and curious articles—window-panes, mirrors, vases, beads, goblets, lamps, lenses of telescopes and microscopes—were fashioned from so brittle a material, and how the material itself was made.

It was a wide-spreading, irregular pile, with brick walls, and two immense, tapering, tall, round chimneys soaring up into the blue sky above its roofs. The train let them off at a platform near by, and then moved on past the rear of the factory.

“Glass works always like to be near a railroad or a wharf, I find,” said the Doctor.

Lawrence said he supposed they sent off heavy freights.

“Yes, but those are a trifle compared with the freights that come to them. Look! there is a coal train switching off and backing up to the yard. They buy fuel by the cargo, as we do by the ton, and stuff it up those huge chimneys. But what is so heavy when it goes in is light enough when it goes out.” They looked up at the cloud which poured out of one of the great flues, and stretched away horizontally, in a long, black streamer, high over the adjacent city. “Some of it flies off in smoke, which we can see, but more of it in gases, which we cannot see; and the wind might blow away the ashes. Yet,” said the Doctor, as they walked on, “not an atom of the coal is really destroyed; it can’t be destroyed; it only changes form.”

Going around to the front of the factory, they entered a small door beside a large gate, passed through the office, where the Doctor seemed to be acquainted, and thence through rooms full of wonderful things, which Lawrence wished to stop at once and examine. But his uncle said, “No; we shall come around to these in due time. In visiting a place like this, if you really wish to learn much about it, the way is to begin at the beginning. Now let me see.”

They entered the spacious rear yard of the factory from one side, just as the coal train backed into it from the other.

“Ah! there is the gaffer!” said the Doctor. “Do you know what a gaffer is?”

“Laugher, one who laughs; quaffer, one who quaffs; gaffer, one who—gaffs, I guess,” said Lawrence, smiling; “though what gaffing is, I don’t know more than the man in the moon.”

“He sees us; we’ll ask him,” said the Doctor.

A short, solid-looking man, in an easy slouched hat and a loose business-coat, who was giving a gang of men directions about unloading the coal, left them, on seeing the Doctor, and came and shook hands with him very cordially. Somehow the Doctor seemed to know everybody.

“This is my nephew,”—and Lawrence had the honor of shaking hands with a gaffer. “By the way,” added the Doctor, “I have often wondered why it is you are called a gaffer. What is the meaning of the word?”

“I don’t know; it’s a name we’re called by,” said the man. “The foreman of any other factory than glass works is called a foreman or boss,—or superintendent, if you wish to be very smart. But the foreman of a glass-house is always the gaffer,—though I doubt if any one can tell you why.”

“Ah! I have it! I have it!” cried the Doctor, tapping Lawrence on the shoulder with his cane in such a way that the boy suspected he had “had it” all the while,—for he was a knowing old head, and he had a habit of testing other people’s knowledge of a subject before bringing out his own. “But I sha’n’t tell; for if it gets out I shall lose the honor of the discovery. I’ll send the word, with the etymology, to one of the big-dictionary makers. For you won’t find it in any dictionary as a name applied to the foreman of a glass-house. You’ll find ‘Gaffer; an old man,’—gaffer and gamma being ancient abbreviations of grandfather and grandmother.”

“I have it! I have it!” cried Lawrence, in his turn, having caught the bait his uncle threw out; for it was also the Doctor’s habit, in keeping back his knowledge of a question, to let fall hints which should lead his young friends to solve it for themselves, thus developing their thinking faculties, and fixing more securely in their minds what they learned.

“What, young man! have you got my secret away from me? Prove it.”

“Gaffer used to mean grandfather, or old man. Now, in some shops, the boss is called old man. Just so, I suppose, he used to be called gaffer; and the name has stuck to him, even after its original meaning has been forgotten.”

“Very well! capital! But why is it that it is applied only to the glass-house foreman?”

That Lawrence could not explain. But the gaffer himself had an idea on that point, which, coming from one of the name and trade, was certainly entitled to consideration.

“I imagine,” he said, “that generally the foremen of glass-houses were older men than the bosses of other trades, for it takes a man who has spent his life in the business, and grown gray in it, to take the management of it. I believe there is no other trade that requires so much care and experience; that must have been especially the case before our modern improvements in building furnaces. Then again, even if other foremen were called gaffers, they might have lost the name, as it went out of use outside of the shop. But while the men of other trades have changed their habits and expressions to suit the times, glass-makers, until within a few years, never changed anything. That was owing to their exclusiveness. They were a class by themselves. Their art was a wonderful one; it was the most ancient of arts,—it was thought perfect, and not to be improved; they were jealous of having it become known to any that were not regularly initiated into it; and so they kept it shut up from the world, and surrounded by mystery, almost as much as if they had been members of a secret society.”

“Well,” laughed the Doctor, “three heads are better than one; and I think, together, we have sifted out the meaning of the word gaffer pretty thoroughly. And now for getting at the secrets of this mystic order. Gaffer, what have you got to show us? Lawrence, what shall we see first?”

“Let’s see where the coal goes, since we have begun with the coal,” said Lawrence.

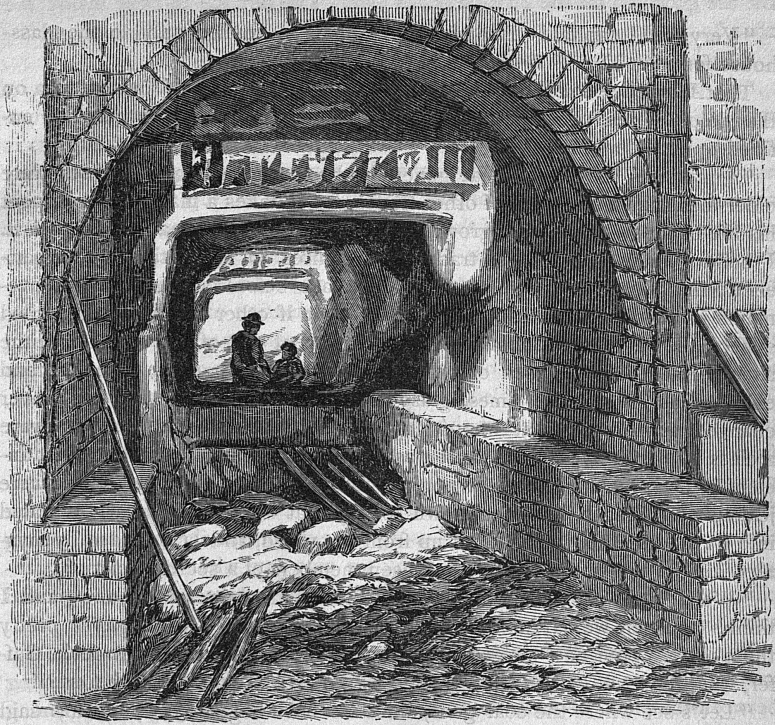

“Then you’d like to see the cave?” said the gaffer.

Lawrence had no more distinct idea of what a glass-house cave was, than he had had of a gaffer. But cave sounded romantic. It suggested the subterranean,—something deep and dark and mysterious. So he said, boldly, that he should like very much to see the cave.

“Come with me,” said the gaffer. “We use coal for various purposes, but the bulk of it goes the way I’ll show you.”

They were going towards one of the great towering chimneys. But, just before reaching it, the gaffer, to Lawrence’s great delight, turned suddenly, and stepped down into a passage that dived (romantically speaking) deep into the earth. The lad and the Doctor followed, leaving daylight and the upper air behind them, and now saw before them a great glow of fire shining in the midst of surrounding darkness. That is to say, in the language of plain fact, they descended a flight of steps into a sort of cellar, from which, I regret to say, daylight was not wholly excluded, and found themselves—But we will let the gaffer speak.

“Here is where we get our draught. We are now under the large chimney,—cone, we call it. It is supported by these piers. Right in the centre, between them, you see that horizontal grate, with the fire from above shining through; that is in the bottom of the furnace,—what we call the eye.”

“It’s an awful, fiery-red eye!” said Lawrence. “Don’t it look like some horrible, one-eyed dragon, shut up there, and glaring down at us through those iron bars?”

“Not at all; not in the least,” said the Doctor, who could be dreadfully prosaic when he saw young people inclined to be too romantic. “It looks to me like a very hot fire. I should think your grates would burn out fast.”

“They last longer than one would suppose,” said the gaffer. “Iron bars like these will stand a couple of years. The draught of cold air rushing up through them, and the dead cinders accumulating, keep them comparatively cool.”

“How do you get rid of the clinkers?” said Lawrence, who remembered his bitter experience cleaning the stoves at home. “I suppose you let the fire go out once in a while.”

“We let this fire go down about once in five or six years,” said the gaffer. “Then it takes three weeks’ steady firing up to get a heat we can work with.”

“Three weeks!” exclaimed Lawrence, astonished. “Then it would hardly pay to let the fire go down for the clinkers!”