* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This ebook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the ebook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the ebook. If either of these conditions applies, please contact a FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. IF THE BOOK IS UNDER COPYRIGHT IN YOUR COUNTRY, DO NOT DOWNLOAD OR REDISTRIBUTE THIS FILE.

Title: Race, Language and Culture

Date of first publication: 1940

Author: Franz Boas

Date first posted: Mar. 4, 2015

Date last updated: Mar. 4, 2015

Faded Page eBook #20150313

This ebook was produced by: Alison Hadwin, Delphine Lettau, David T. Jones, Alex White & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

Transcriber’s Note

This document makes extensive use of special unicode characters, and of unicode combining characters. Some devices and/or fonts may fail to display all characters correctly. It may not be appropriate for reading in either small devices or in text format. Most current browsers render fine.

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA · MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

OF CANADA, Limited

TORONTO

RACE, LANGUAGE

AND CULTURE

By

FRANZ BOAS

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1940

Copyright, 1940,

By FRANZ BOAS

All rights reserved—no part of this book may be

reproduced in any form without permission in writing

from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes

to quote brief passages in connection with a review

written for inclusion in magazine or newspaper.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published February, 1940.

Anthropology, the science of man, is often held to be a subject that may satisfy our curiosity regarding the early history of mankind, but of no immediate bearing upon problems that confront us. This view has always seemed to me erroneous. Growing up in our own civilization we know little how we ourselves are conditioned by it, how our bodies, our language, our modes of thinking and acting are determined by limits imposed upon us by our environment. Knowledge of the life processes and behavior of man under conditions of life fundamentally different from our own can help us to obtain a freer view of our own lives and of our life problems. The dynamics of life have always been of greater interest to me than the description of conditions, although I recognize that the latter must form the indispensable material on which to base our conclusions.

My endeavors have largely been directed by this point of view. In the following pages I have collected such of my writings as, I hope, will prove the validity of my point of view.

The material presented here is not intended to show a chronological development. The plan is rather to throw light on the problems treated. General discussions are followed by reports on special investigations on the results of which general viewpoints are based.

On the whole I have left the statements as they first appeared. Only in the discussion of the problems of stability of races and of growth which extend over many years, has scattered material been combined. In these the mathematical problems have been omitted and diagrams have been substituted for numerical tables. Here and there reviews and controversies have been included where they seemed relevant and of importance for the clearer statement of theories.

The terms “race” and “racial” are throughout used in the sense that they mean the assembly of genetic lines represented in a population.

It is natural that the earlier papers do not include data available at the present time. I have not made any changes by introducing new material because it seemed to me that the fundamental theoretical treatment of problems is still valid. In a few cases footnotes in regard to new investigations or criticisms of the subject matter have been added.

I have included two very early general papers at the end of the book because they indicate the general attitude underlying my later work.

I wish to express my sincere thanks to Dr. Alexander Lesser whose help and advice in the selection of material has been of greatest value.

Franz Boas

Columbia University

November 29, 1939

RACE

| PAGES |

| RACE AND PROGRESS (1931) | 3-17 |

| MODERN POPULATIONS OF AMERICA (1915) | 18-27 |

| REPORT ON AN ANTHROPOMETRIC INVESTIGATION OF THE POPULATION OF THE UNITED STATES (1922) | 28-59 |

| CHANGES IN BODILY FORM OF DESCENDANTS OF IMMIGRANTS (1910-1913) | 60-75 |

| NEW EVIDENCE IN REGARD TO THE INSTABILITY OF HUMAN TYPES (1916) | 76-81 |

| INFLUENCE OF HEREDITY AND ENVIRONMENT UPON GROWTH (1913) | 82-85 |

| THE TEMPO OF GROWTH OF FRATERNITIES (1935). | 86-88 |

| CONDITIONS CONTROLLING THE TEMPO OF DEVELOPMENT AND DECAY (1935) | 89-93 |

| REMARKS ON THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY OF CHILDREN (1912) | 94-102 |

| GROWTH (1892-1939, revised and condensed) | 103-130 |

| STATISTICAL STUDY OF ANTHROPOMETRY (1902) | 131-137 |

| THE HALF-BLOOD INDIAN (1894) | 138-148 |

| REVIEW OF DR. PAUL EHRENREICH, “ANTHROPOLOGISCHE STUDIEN UEBER DIE UREINWOHNER BRASILIENS” (1897) | 149-154 |

| REVIEW OF WILLIAM Z. RIPLEY, “THE RACES OF EUROPE” (1899) | 155-159 |

| REVIEW OF ROLAND B. DIXON, “THE RACIAL HISTORY OF MAN” (1923) | 160-164 |

| SOME RECENT CRITICISM OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY (1899) | 165-171 |

| THE RELATIONS BETWEEN PHYSICAL AND SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY (1936) | 172-175 |

| THE ANALYSIS OF ANTHROPOMETRICAL SERIES (1913) | 176-180 |

| THE MEASUREMENT OF DIFFERENCES BETWEEN VARIABLE QUANTITIES (1922) | 181-190 |

| RACE AND CHARACTER (1932) | 191-195 |

LANGUAGE

| INTRODUCTION TO INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AMERICAN LINGUISTICS (1917) | 199-210 |

| THE CLASSIFICATION OF AMERICAN LANGUAGES (1920) | 211-218 |

| CLASSIFICATION OF AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES (1929) | 219-225 |

| SOME TRAITS OF THE DAKOTA LANGUAGE (1937) | 226-231 |

| METAPHORICAL EXPRESSION IN THE LANGUAGE OF THE KWAKIUTL INDIANS (1929) | 232-239 |

CULTURE

| THE AIMS OF ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH (1932) | 243-259 |

| SOME PROBLEMS OF METHODOLOGY IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES (1930) | 260-269 |

| THE LIMITATIONS OF THE COMPARATIVE METHOD OF ANTHROPOLOGY (1896) | 270-280 |

| THE METHODS OF ETHNOLOGY (1920) | 281-289 |

| EVOLUTION OR DIFFUSION (1924) | 290-294 |

| REVIEW OF GRAEBNER, “METHODE DER ETHNOLOGIE” (1911) | 295-304 |

| HISTORY AND SCIENCE IN ANTHROPOLOGY: A REPLY (1936) | 305-311 |

| THE ETHNOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF ESOTERIC DOCTRINES (1902) | 312-315 |

| THE ORIGIN OF TOTEMISM (1910) | 316-323 |

| THE HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN RACE (1911) | 324-330 |

| ETHNOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN CANADA (1910) | 331-343 |

| RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN NORTH-WEST AMERICA AND NORTH-EAST ASIA (1933) | 344-355 |

| THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE KWAKIUTL (1920) | 356-369 |

| THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE TRIBES OF THE NORTH PACIFIC COAST (1924) | 370-378 |

| THE GROWTH OF THE SECRET SOCIETIES OF THE KWAKIUTL (1896) | 379-383 |

| THE RELATIONSHIP SYSTEM OF THE VANDAU (1922) | 384-396 |

| THE DEVELOPMENT OF FOLK-TALES AND MYTHS (1916) | 397-406 |

| INTRODUCTION TO JAMES TEIT, “THE TRADITIONS OF THE THOMPSON INDIANS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA” (1898) | 407-424 |

| THE GROWTH OF INDIAN MYTHOLOGIES (1895) | 425-436 |

| DISSEMINATION OF TALES AMONG THE NATIVES OF NORTH AMERICA (1891) | 437-445 |

| REVIEW OF G. W. LOCHER, “THE SERPENT IN KWAKIUTL RELIGION: A STUDY IN PRIMITIVE CULTURE” (1933) | 446-450 |

| MYTHOLOGY AND FOLK-TALES OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS (1914) | 451-490 |

| STYLISTIC ASPECTS OF PRIMITIVE LITERATURE (1925) | 491-502 |

| THE FOLK-LORE OF THE ESKIMO (1904) | 503-516 |

| ROMANCE FOLK-LORE AMONG AMERICAN INDIANS (1925) | 517-524 |

| SOME PROBLEMS IN NORTH AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY (1902) | 525-529 |

| ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN THE VALLEY OF MEXICO BY THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, 1911-12 (1912) | 530-534 |

| REPRESENTATIVE ART OF PRIMITIVE PEOPLE (1916) | 535-540 |

| REVIEW OF MACCURDY, “STUDY OF CHIRIQUIAN ANTIQUITIES” (1911) | 541-545 |

| THE DECORATIVE ART OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS (1903) | 546-563 |

| DECORATIVE DESIGNS OF ALASKAN NEEDLECASES: A STUDY IN THE HISTORY OF CONVENTIONAL DESIGNS, BASED ON MATERIALS IN THE U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM (1908) | 564-592 |

| THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE ESKIMO OF EAST GREENLAND (1909) | 593-595 |

| THE IDEA OF THE FUTURE LIFE AMONG PRIMITIVE TRIBES (1922) | 596-607 |

| THE CONCEPT OF SOUL AMONG THE VANDAU (1920) | 608-611 |

| RELIGIOUS TERMINOLOGY OF THE KWAKIUTL (1927) | 612-618 |

MISCELLANEOUS

| ADVANCES IN METHODS OF TEACHING (1898) | 621-625 |

| THE AIMS OF ETHNOLOGY (1888) | 626-638 |

| THE STUDY OF GEOGRAPHY (1887) | 639-647 |

CHANGES IN BODILY FORM OF DESCENDANTS OF IMMIGRANTS

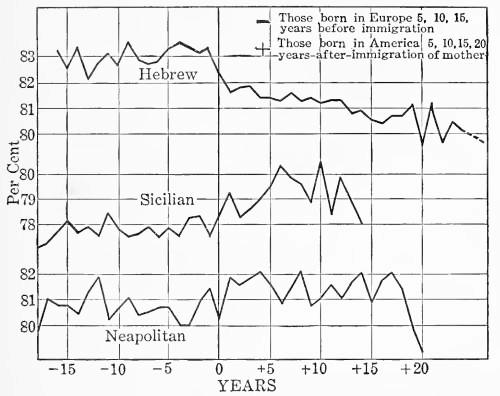

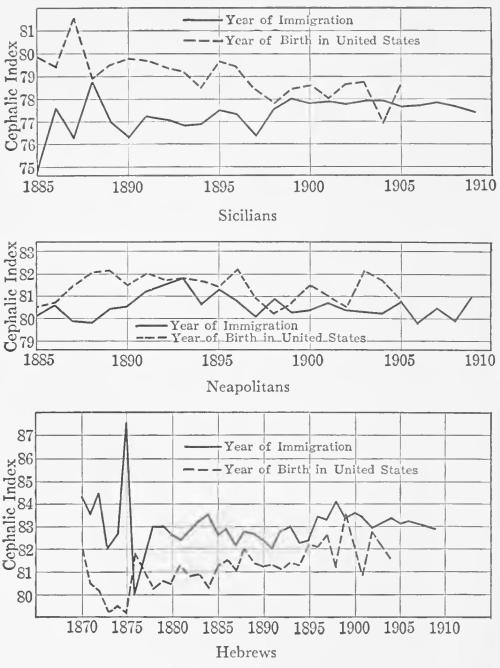

| Fig. 1. | Cephalic index of immigrants and their descendants |

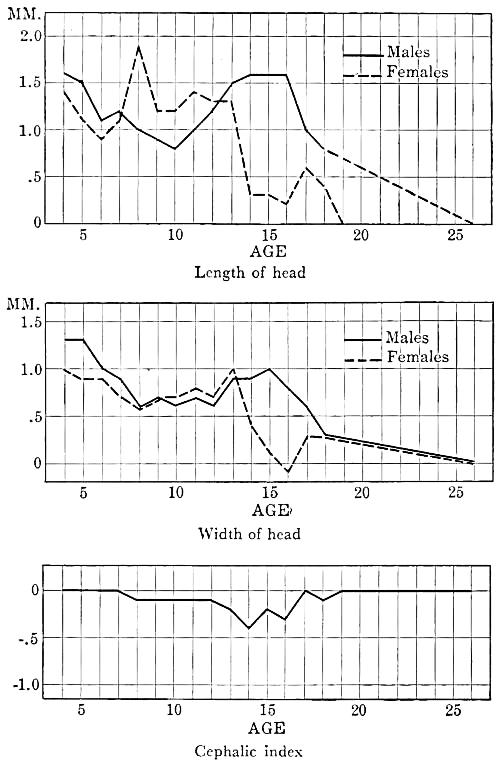

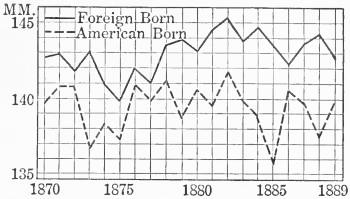

| Fig. 2. | Changes of head measurements during period of growth |

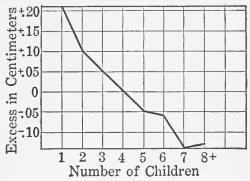

| Fig. 3. | Excess of stature over average stature for families of various sizes |

| Fig. 4. | Cephalic index of individuals born in Europe who immigrated in certain years compared with that of American-born descendants of mothers who immigrated in corresponding years |

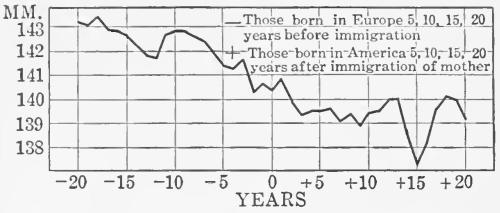

| Fig. 5. | Width of face of adult Bohemian males born in Europe who immigrated in certain years, compared with that of American-born descendants of mothers who immigrated in corresponding years |

| Fig. 6. | Width of face of Bohemians and their descendants |

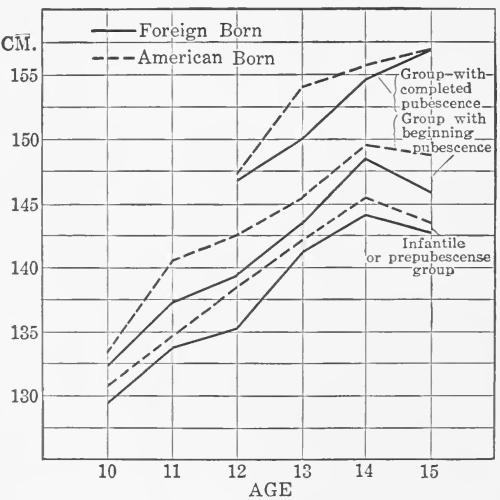

| Fig. 7. | Relation between stature and maturity for foreign-born and American-born boys |

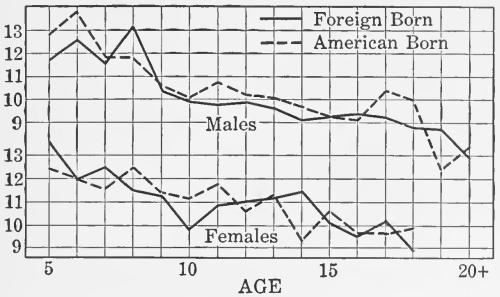

| Fig. 8. | Color of hair of foreign-born and American-born Hebrews, showing the increase of pigmentation with increasing age |

THE TEMPO OF GROWTH OF FRATERNITIES

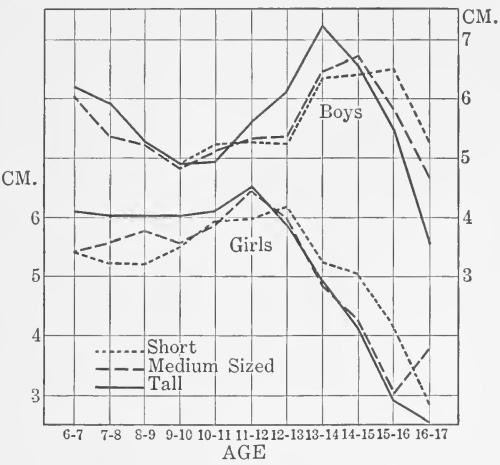

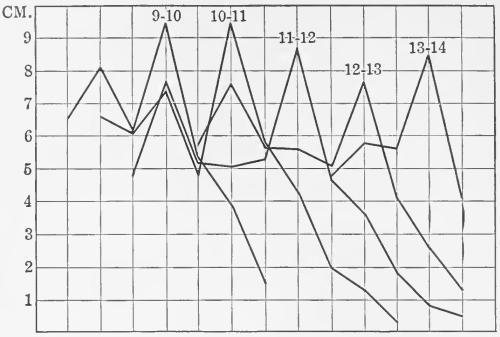

| Fig. 1. | Annual growth of brothers and sisters, tall, medium-sized and short, at the selected ages of 7, 9, 11, and 13 years. Continuous observations. Hebrew Orphan Asylum |

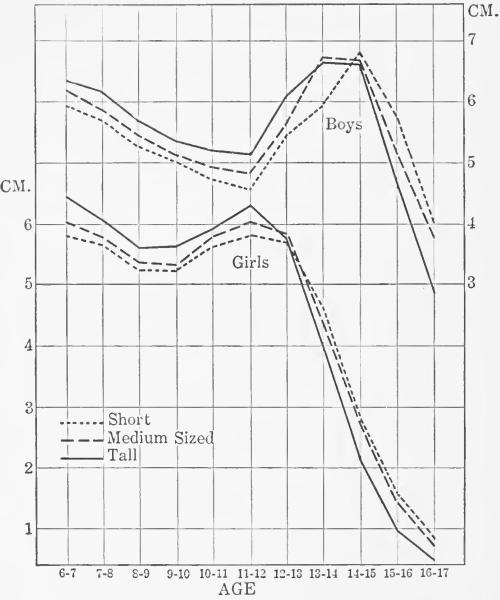

| Fig. 2. | Annual growth of brothers and sisters, tall, medium-sized and short, at the selected ages of 7, 9, 11, and 13 years. Continuous observations. Horace Mann School |

GROWTH

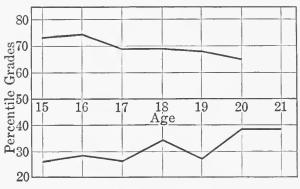

| Fig. 1. | Change in percentile position of individuals starting at 15 years with the percentile grades of 27 and 73 respectively. U. S. Naval Cadets |

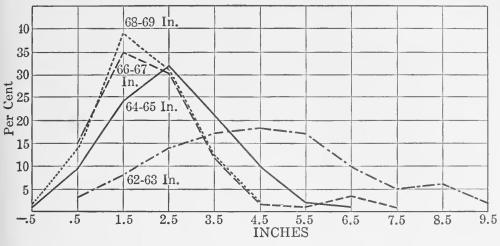

| Fig. 2. | Amount of total growth from 16 years to adult of males of various statures |

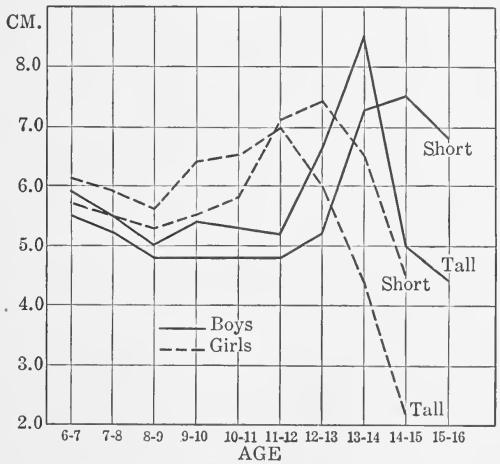

| Fig. 3. | Average amount of growth of tall and short children. Worcester, Massachusetts |

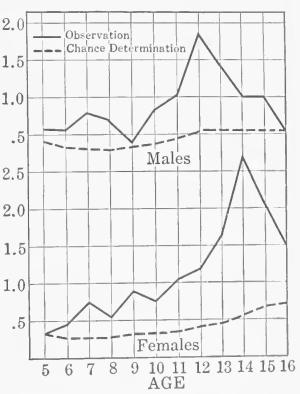

| Fig. 4. | Variability of social and national groups as observed and as expected, if only chance determined the variability |

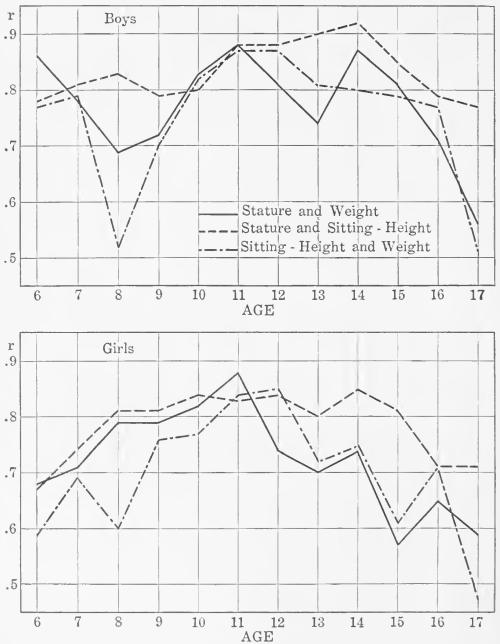

| Fig. 5. | Correlation of measurements during period of growth. Worcester, Massachusetts |

| Fig. 6. | Variability of stature of boys and girls having the same periods of maximum growth, compared with variability of total series. Horace Mann School |

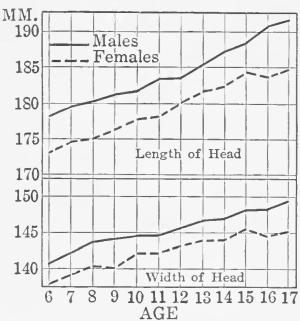

| Fig. 7. | Length and width of head of boys and girls |

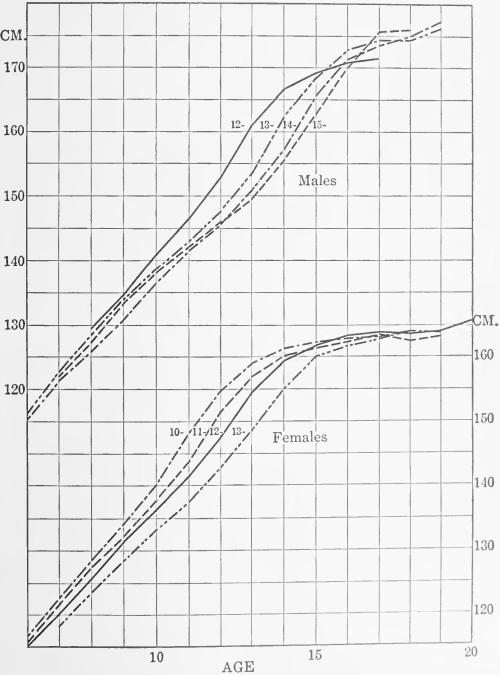

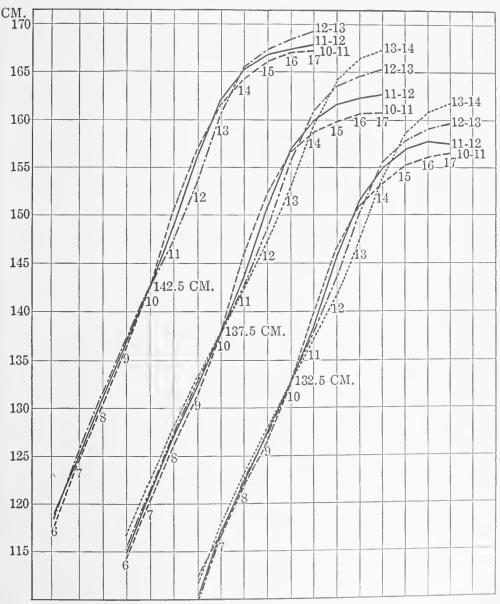

| Fig. 8. | Growth curves of boys and girls for those having maximum rate of growth at the same time. Horace Mann School |

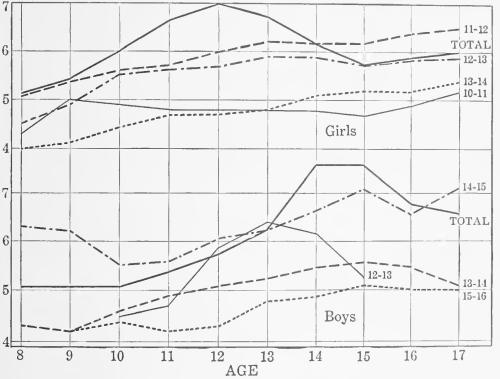

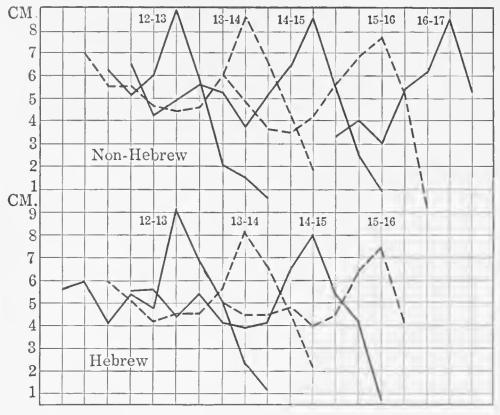

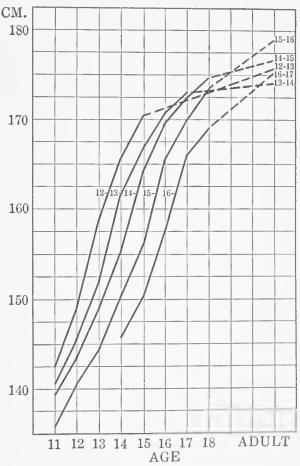

| Fig. 9. | Annual increments for boys who have the same periods of maximum rate of growth. Annual intervals to be read from apex of each curve. Horace Mann School |

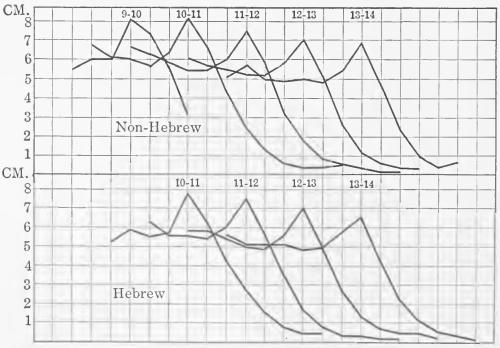

| Fig. 10. | Annual increments for girls who have the same periods of maximum rate of growth. Annual intervals to be read from apex of each curve. Horace Mann School |

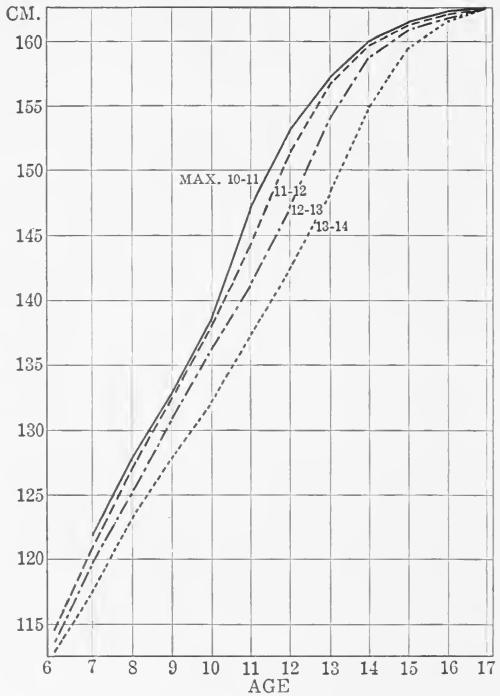

| Fig. 11. | Growth curves of girls who have the same stature at 10 years and the same period of maximum rate of growth. Horace Mann School |

| Fig. 12. | Growth curves of girls who have the same stature at 17 years and the same periods of maximum rate of growth. Horace Mann School |

| Fig. 13. | Growth of boys in the Newark Academy with the same period of maximum rate of growth |

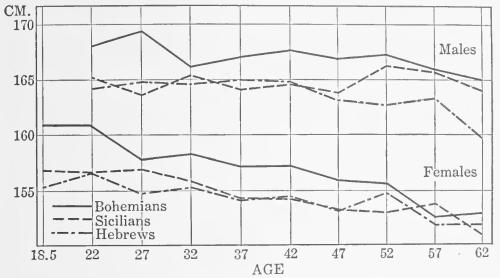

| Fig. 14. | Decrease of stature with increasing age |

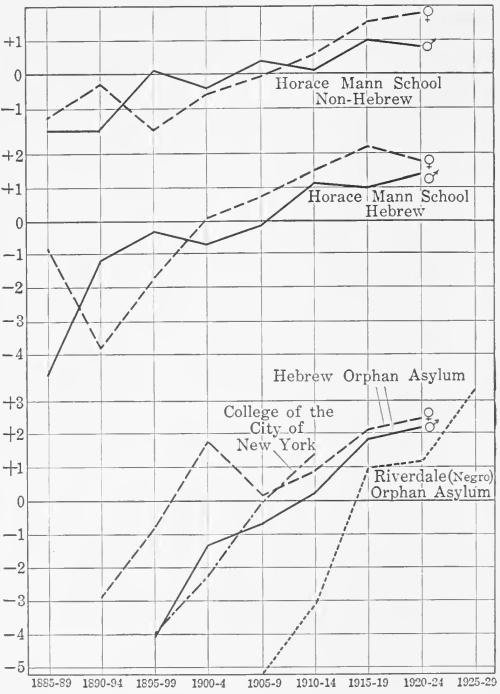

| Fig. 15. | Difference between average stature in centimeters, of a number of total series (regardless of year of birth) and of subgroups of individuals born in quinquennial intervals. All ages combined |

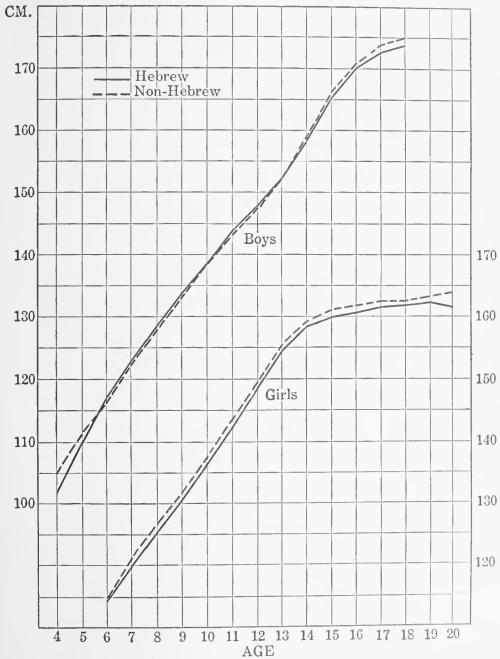

| Fig. 16. | Growth curves for Hebrew boys and girls |

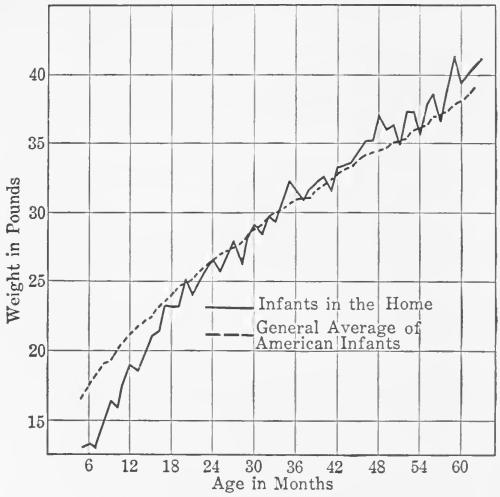

| Fig. 17. | Weights of Hebrew infants in an orphan asylum compared with the weights of infants of the general American population |

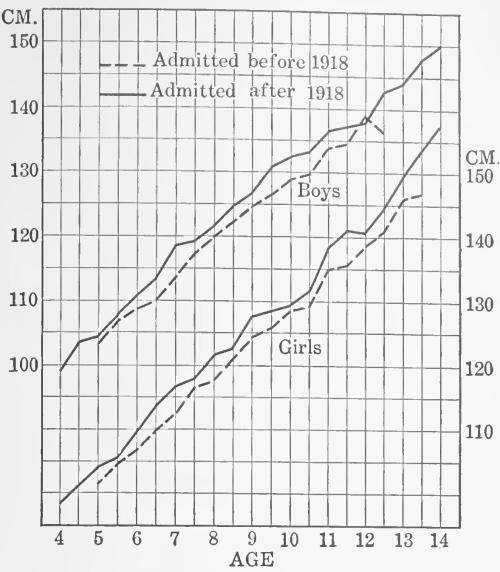

| Fig. 18. | Statures of children admitted to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum before and after 1918 |

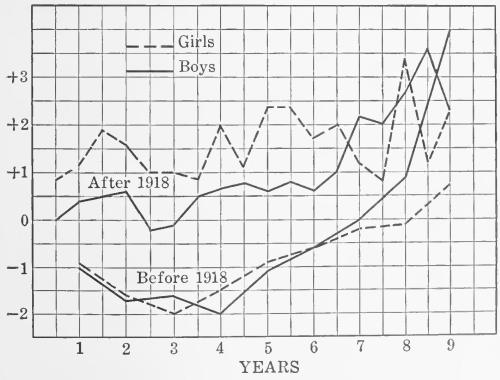

| Fig. 19. | Difference between average statures in centimeters of children of all ages at time of admission to the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, and statures after from 1-9 years of residence |

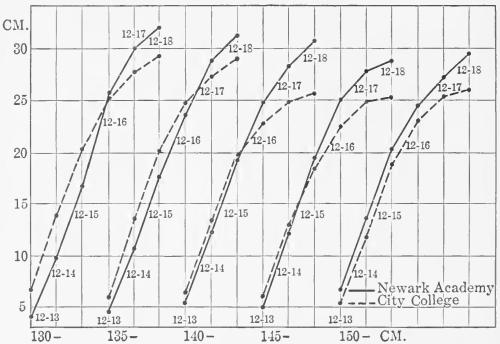

| Fig. 20. | Comparison of growth curves of boys of the same stature at 12 years of age in Newark Academy and in the College of the City of New York. The curves show the amount of growth from 12 years on for boys of statures from 130-150 cm. in 5 cm. groups |

| Fig. 21. | Growth of Non-Hebrew and Hebrew children in Horace Mann School |

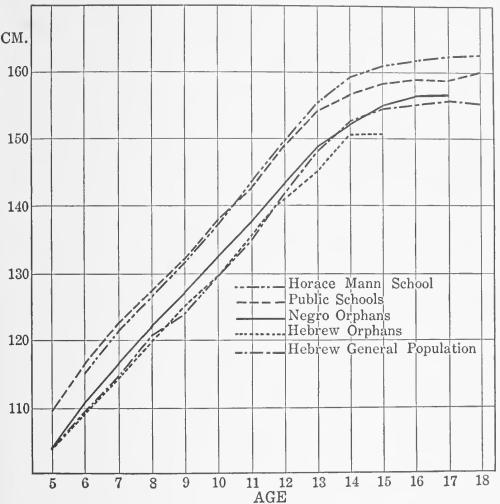

| Fig. 22. | Annual increments for Negro girls having maximum rates of growth at various periods |

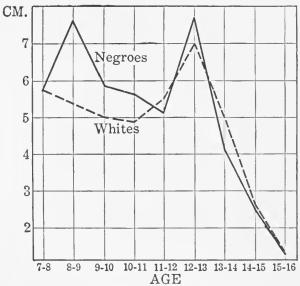

| Fig. 23. | Annual increments of Negro and White girls |

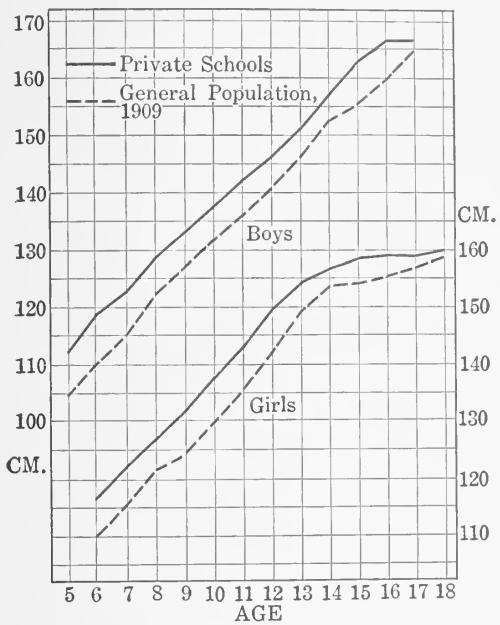

| Fig. 24. | Comparative growth curves of girls |

THE HALF-BLOOD INDIAN

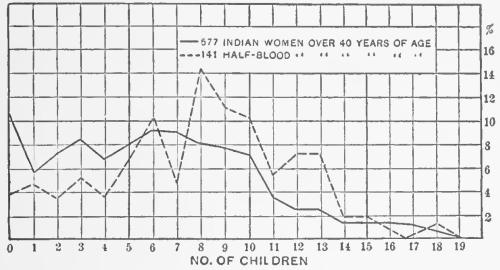

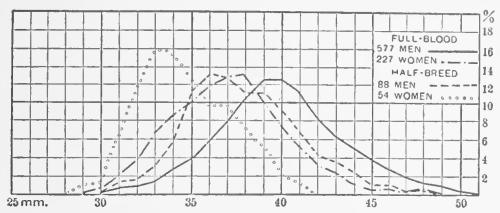

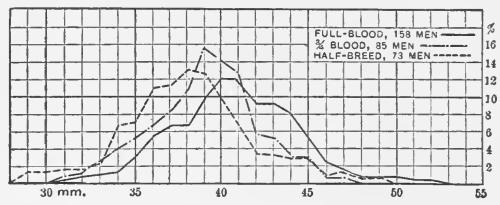

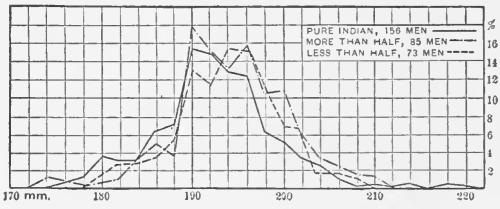

| Fig. 1. | Number of children of Indian women and half-blood women |

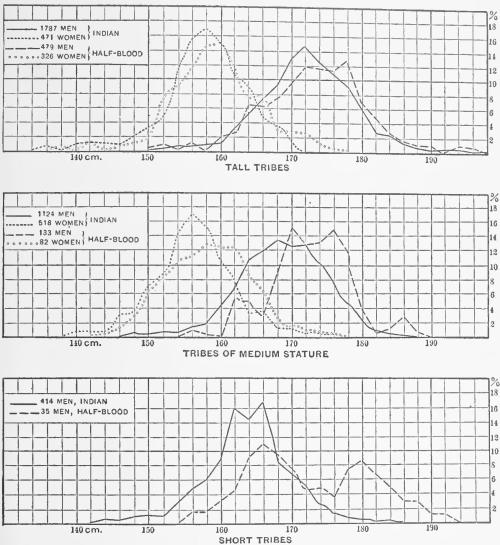

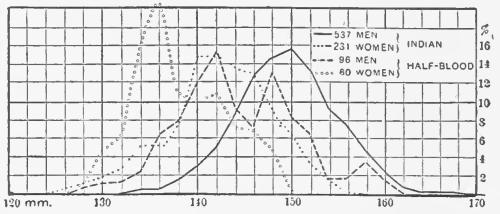

| Fig. 2. | Statures of Indians and of half-bloods |

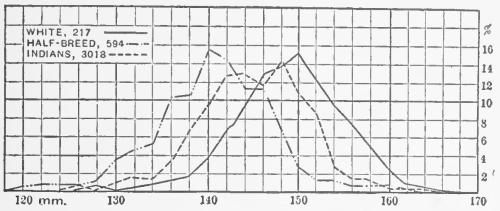

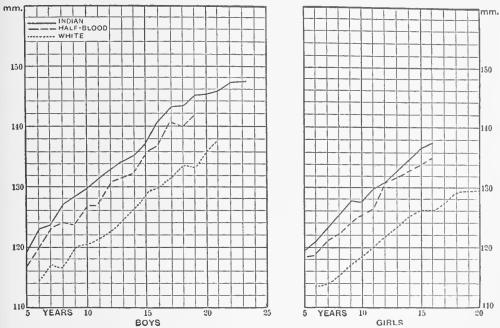

| Fig. 3. | Growth of Indian and half-blood children |

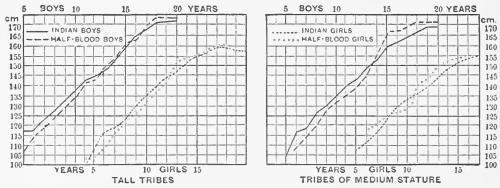

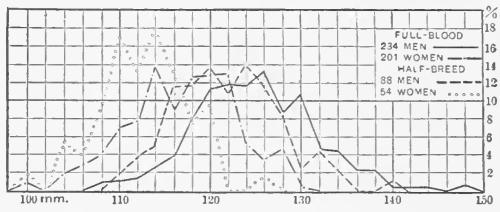

| Fig. 4. | Breadth of face of Indians, half-bloods, and Whites |

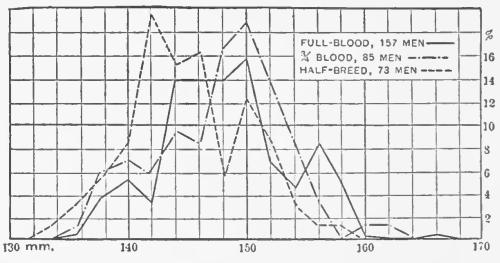

| Fig. 5. | Breadth of face, Sioux |

| Fig. 6. | Breadth of face, eastern Ojibwas |

| Fig. 7. | Breadth of face of Indian, half-blood and White children |

| Fig. 8. | Height of face, Sioux |

| Fig. 9. | Breadth of nose, Sioux |

| Fig. 10. | Breadth of nose, eastern Ojibwas |

| Fig. 11. | Length of head, eastern Ojibwas |

THE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION OF THE KWAKIUTL

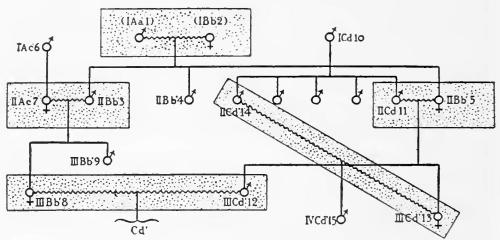

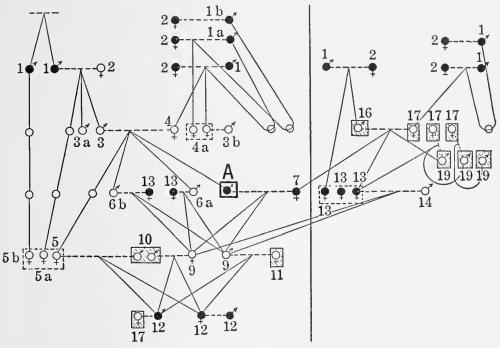

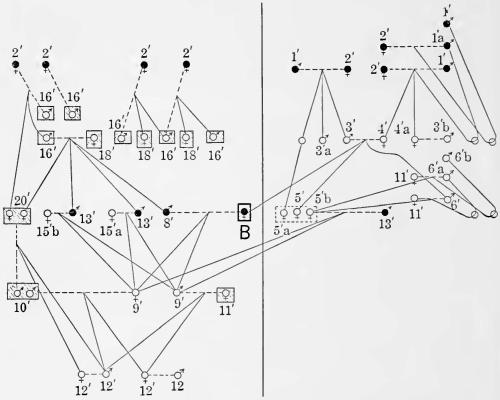

| Fig. 1. | Genealogy illustrating intermarriages |

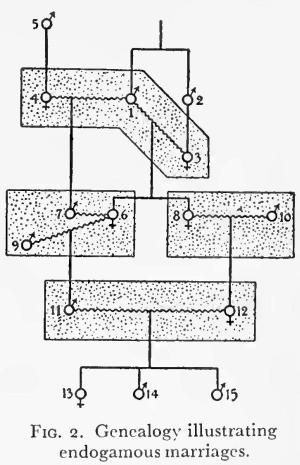

| Fig. 2. | Genealogy illustrating endogamous marriages |

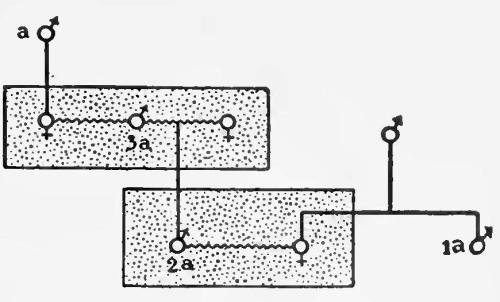

| Fig. 3. | Transfer of position through marriage |

RELATIONSHIP SYSTEM OF THE VANDAU

| Fig. 1. | Relationship system of the Vandau; terms used by man |

| Fig. 2. | Relationship system of the Vandau; terms used by woman |

THE DECORATIVE ART OF THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS

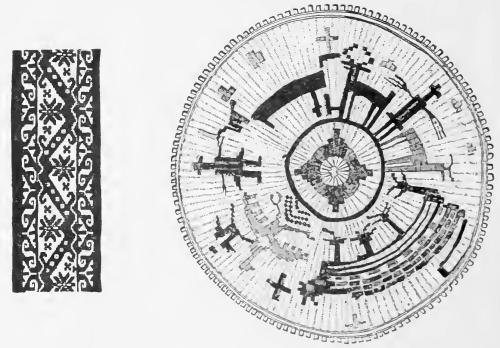

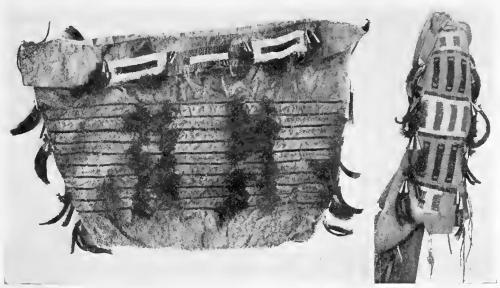

| Fig. 1. | Shaman’s coat. Eskimo, Iglulik |

| Fig. 2. | Man’s costume. Eskimo, Aivilik |

| Fig. 3. | Shaman’s coat. Gold |

| Fig. 4. | Decorated fish skin coat. Gold |

| Fig. 5. | Ceremonial shield and belt for ordinary wear. Huichol. After Lumholtz |

| Fig. 6. | Parfleches. Left, Arapaho; right, Shoshone |

| Fig. 7. | Moccasin |

| Fig. 8. | Embroidered design. Arapaho |

| Fig. 9. | Parfleche. Shoshone |

| Fig. 10. | Embroidered skin bag. Arapaho |

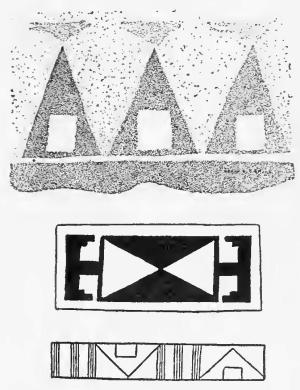

| Fig. 11. | Pueblo patterns. From specimens in the U. S. National Museum |

| Fig. 12. | Quail-tip designs on California and Oregon baskets |

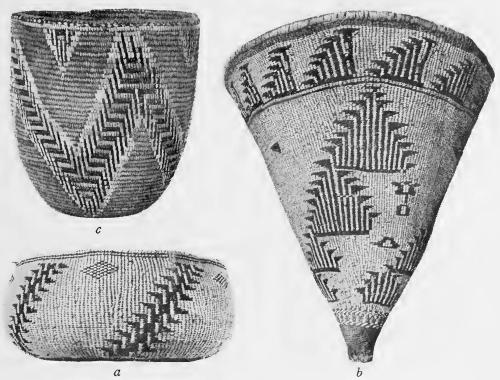

| Fig. 13. | Tlingit baskets. After Emmons |

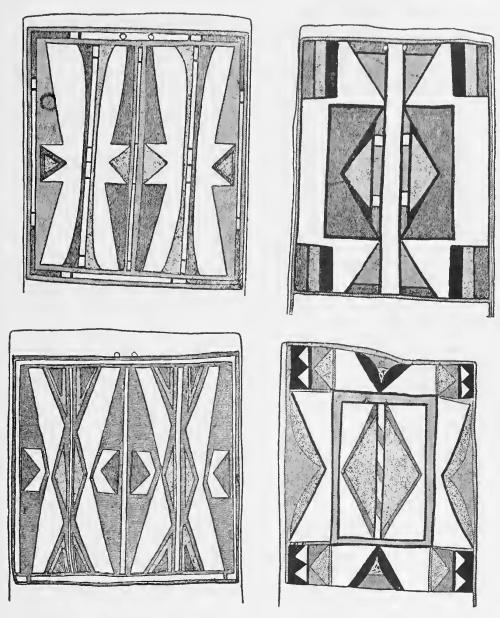

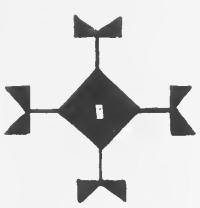

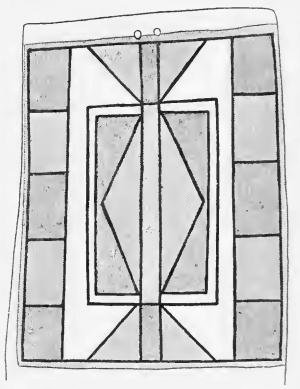

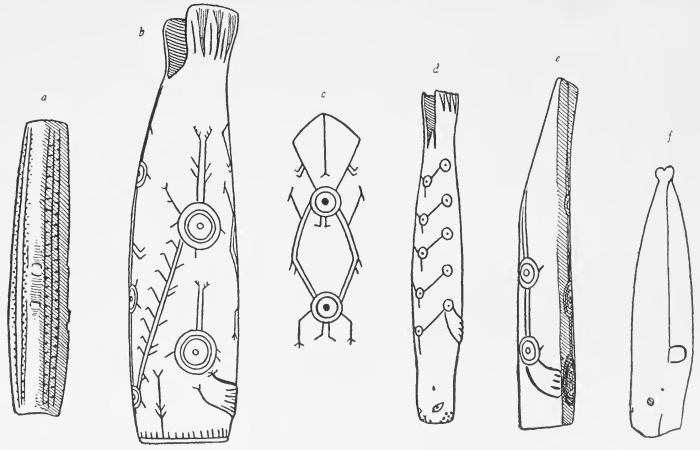

DECORATIVE DESIGNS OF ALASKAN NEEDLECASES

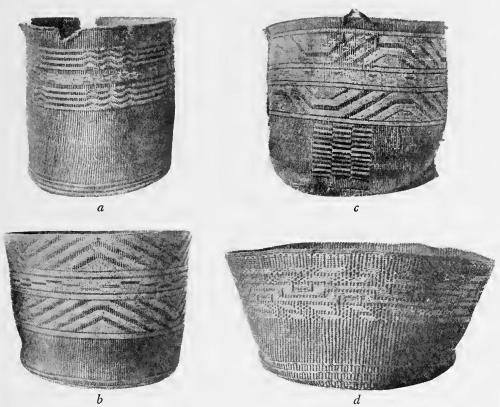

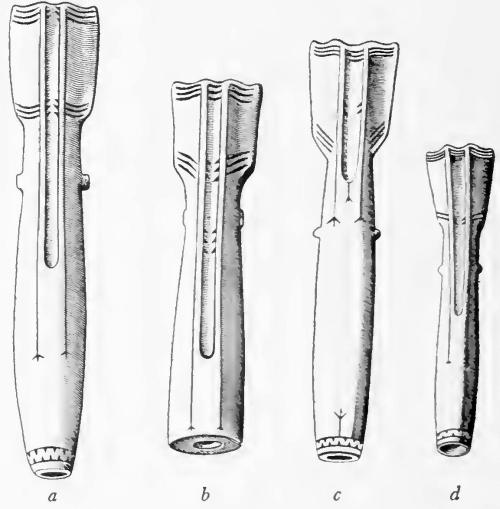

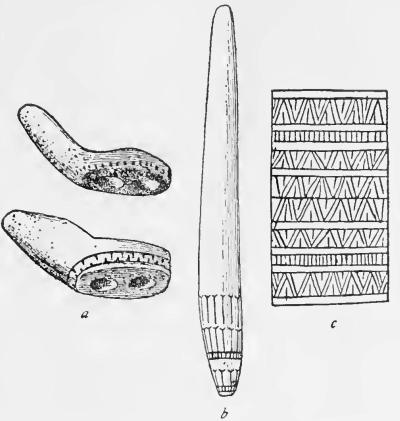

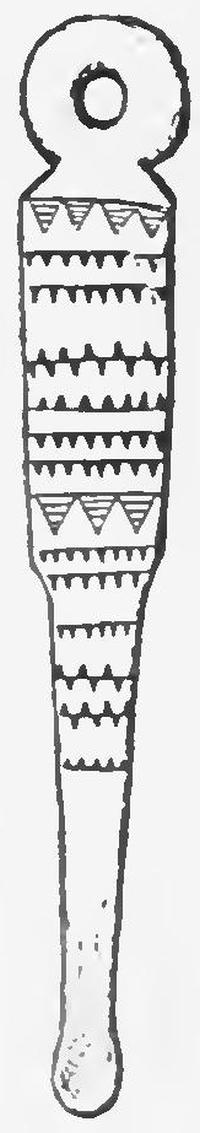

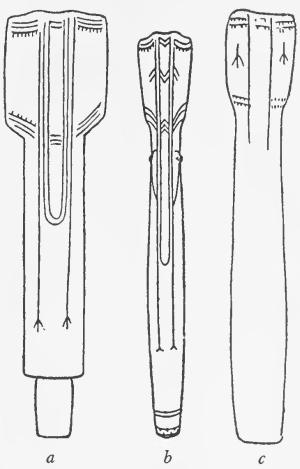

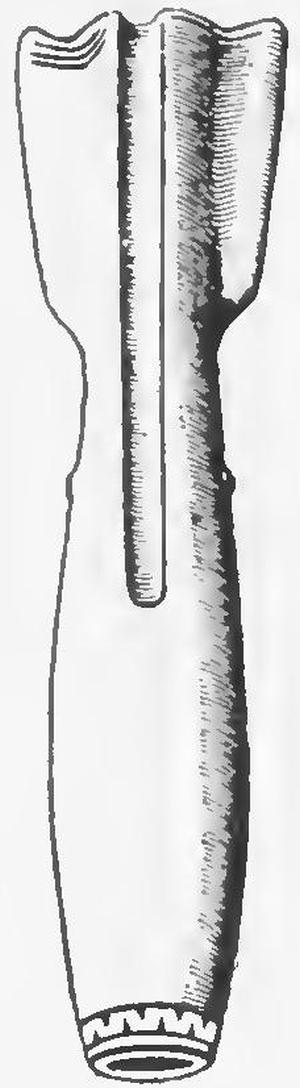

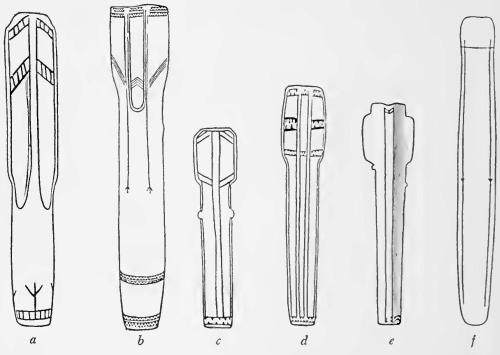

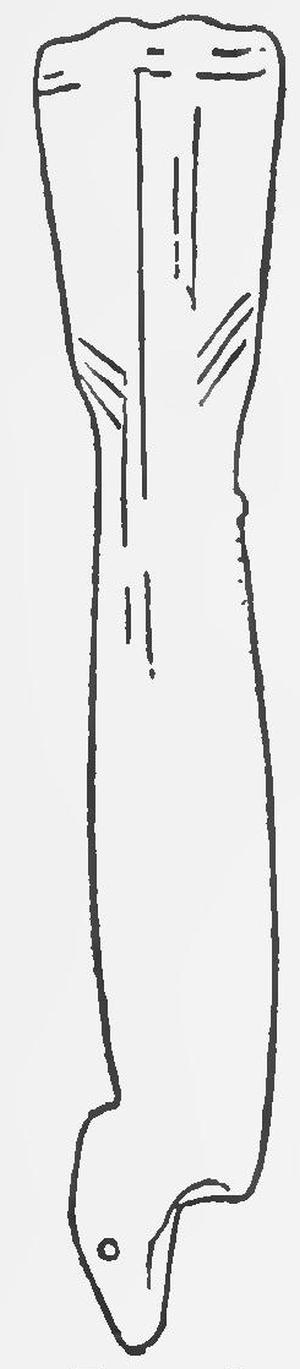

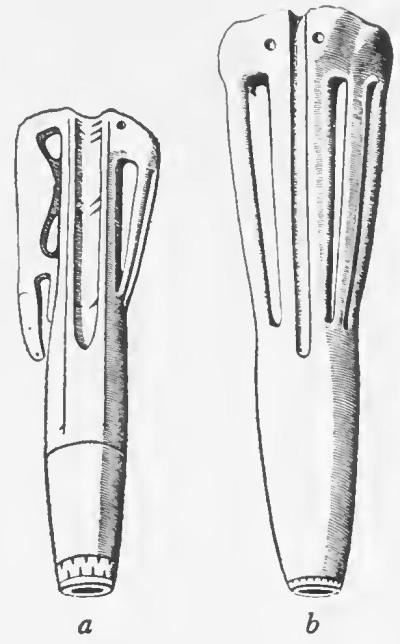

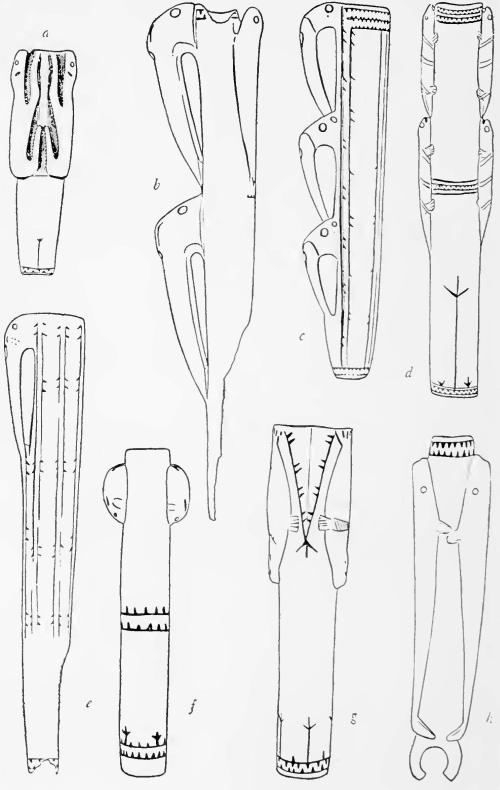

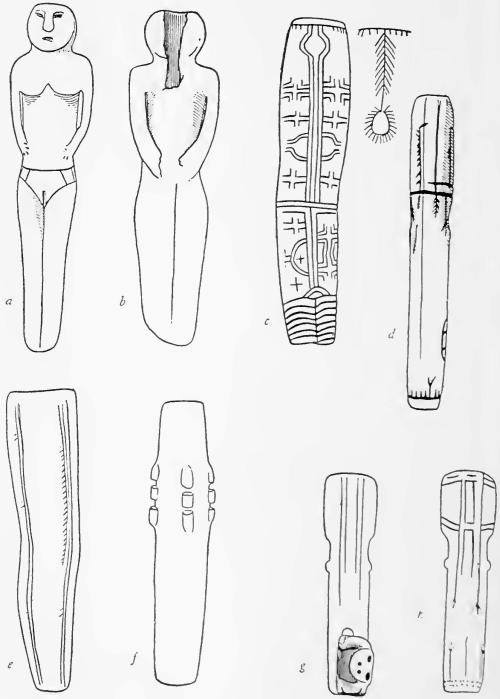

| Fig. 1. | } |

| Fig. 2 and 3. | } Alaskan needlecases |

| Fig. 4 and 5. | } |

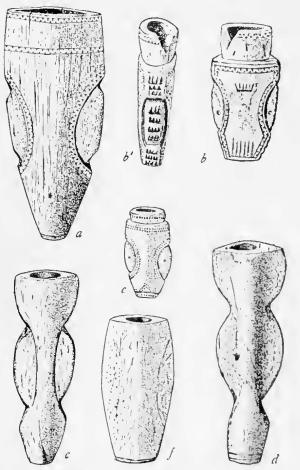

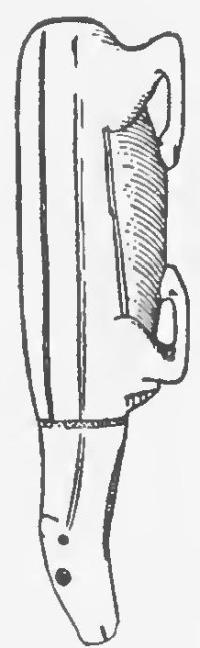

| Fig. 6. | Ivory attachment to line, west coast of Hudson Bay; Creaser, Iglulik; Design of needlecase, King William Land |

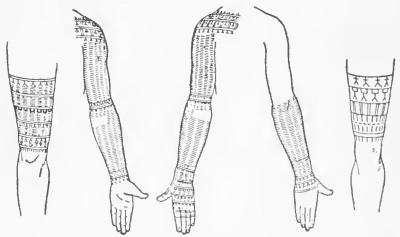

| Fig. 7. | Tattooings from the west coast of Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait |

| Fig. 8. | Ear-spoon, Kamchatka |

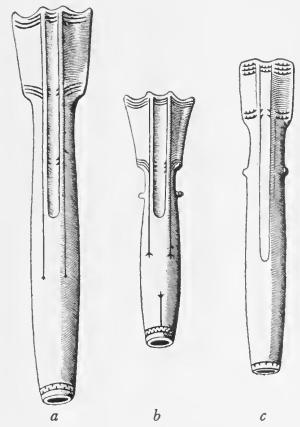

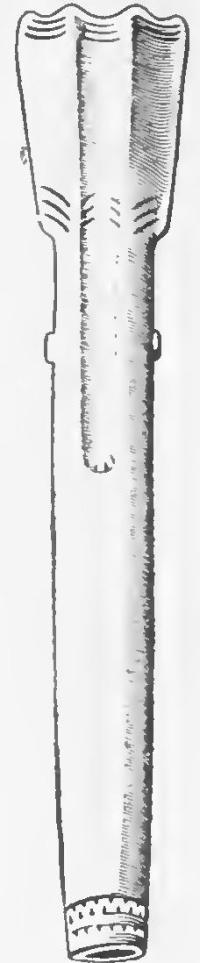

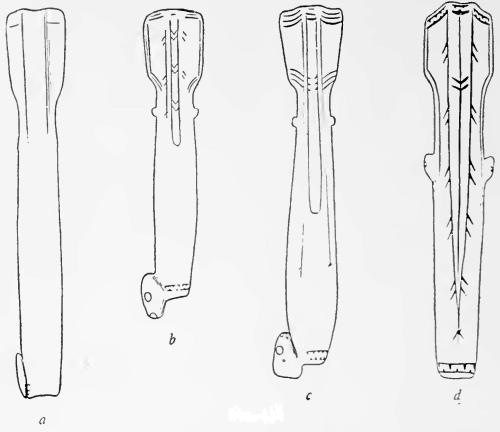

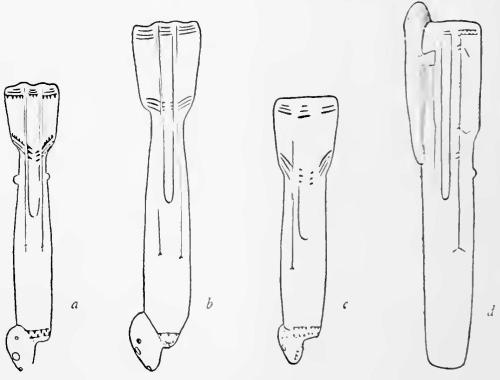

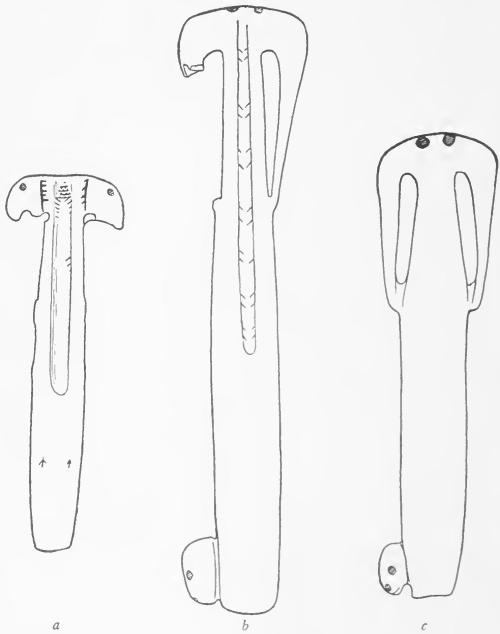

| Fig. 9 and 10. | Alaskan needlecases |

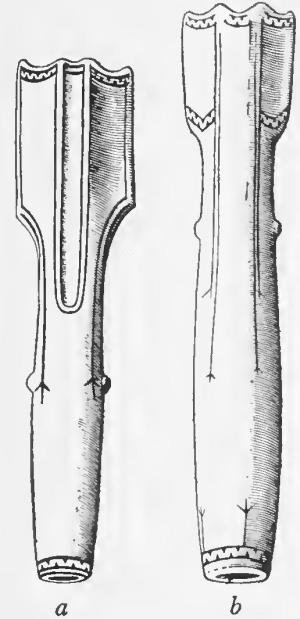

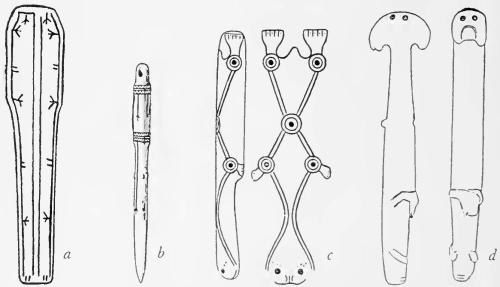

| Fig. 11. | Needlecases from Frozen Strait and Pond’s Bay |

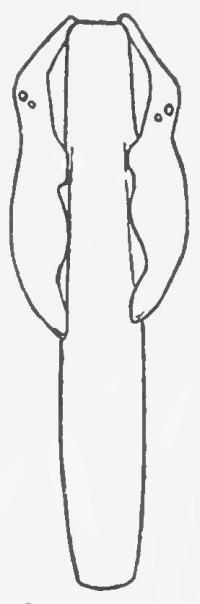

| Fig. 12. | Needlecases from Smith Sound, and Rawlings Bay, west coast of Smith Sound |

| Fig. 13 and 14. | } |

| Fig. 15. | } |

| Fig. 16 and 17. | } |

| Fig. 18 and 19. | } |

| Fig. 20. | } Alaskan needlecases |

| Fig. 21. | } |

| Fig. 22. | } |

| Fig. 23. | } |

| Fig. 24. | } |

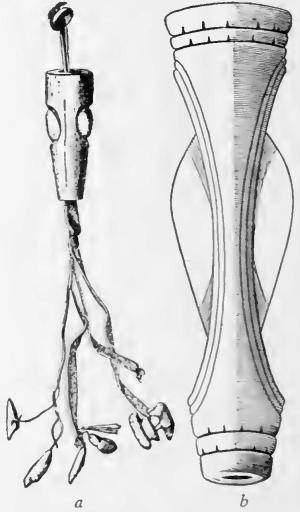

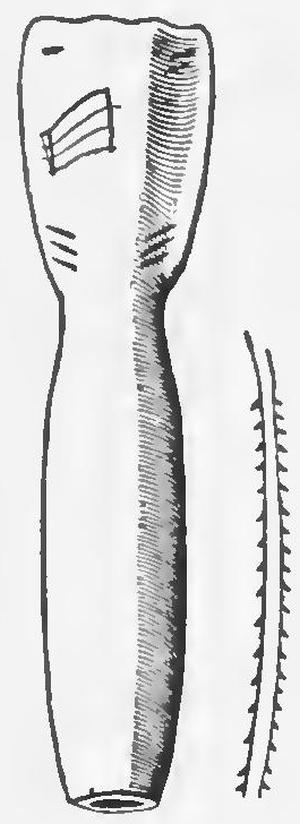

| Fig. 25. | Needlecases and Alaskan awl |

| Fig. 26. | Alaskan needlecases |

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE ESKIMOS OF EAST GREENLAND

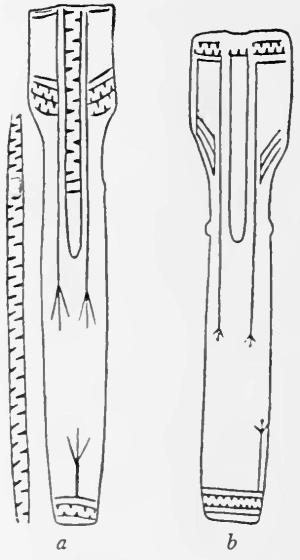

| Fig. 1. | Needlecases, east Greenland |

Permit me to call your attention to the scientific aspects of a problem that has been for a long time agitating our country and which, on account of its social and economic implications, has given rise to strong emotional reactions and has led to varied types of legislation. I refer to the problems due to the intermingling of racial types.

If we wish to reach a reasonable attitude, it is necessary to separate clearly the biological and psychological aspects from the social and economic implications of this problem. Furthermore, the social motivation of what is happening must be looked at not from the narrow point of view of our present conditions but from a wider angle.

The facts with which we are dealing are diverse. The plantation system of the South brought to our shores a large Negro population. Considerable mixture between White masters and slave women occurred during the period of slavery, so that the number of pure Negroes was dwindling continually and the colored population gradually became lighter. A certain amount of intermingling between White and Indian took place, but in the United States and Canada this has never occurred to such a degree that it became an important social phenomenon. In Mexico and many parts of Central and South America it is the most typical case of race contact and race mixture. With the development of immigration the people of eastern and southern Europe were attracted to our country and form now an important part of our population. They differ in type somewhat among themselves, although the racial contrasts are much less than those between Indians or Negroes and Whites. Through Mexican and West Indian immigration another group has come into our country, partly of South European, partly of mixed Negro and mixed Indian descent. To all these must be added the East Asiatic groups, Chinese, Japanese and Filipinos, who play a particularly important rôle on the Pacific Coast.

The first point in regard to which we need clarification refers to the significance of the term race. In common parlance when we speak of a race we mean a group of people that have certain bodily and perhaps also mental characteristics in common. The Whites, with their light skin, straight or wavy hair and high nose, are a race set off clearly from the Negroes with their dark skin, frizzly hair and flat nose. In regard to these traits the two races are fundamentally distinct. Not quite so definite is the distinction between East Asiatics and European types, because transitional forms do occur among normal White individuals, such as flat faces, straight black hair and eye forms resembling the East Asiatic types; and conversely European-like traits are found among East Asiatics. For Negro and White we may speak of hereditary racial traits so far as these radically distinct features are concerned. For Whites and East Asiatics the difference is not quite so absolute, because a few individuals may be found in each race for whom the racial traits do not hold good, so that in a strict sense we cannot speak of absolutely valid hereditary racial traits.

This condition prevails to a much more marked extent among the different, so-called races of Europe. We are accustomed to speak of a Scandinavian as tall, blond and blue-eyed, of a South Italian as short, swarthy and dark-eyed; of a Bohemian as middle-sized, with brown or gray eyes and wide face and straight hair. We are apt to construct ideal local types which are based on our everyday experience, abstracted from a combination of forms that are most frequently seen in a given locality, and we forget that there are numerous individuals for whom this description does not hold true. It would be a rash undertaking to determine the locality in which a person is born solely from his bodily characteristics. In many cases we may be helped in such a determination by manners of wearing the hair, peculiar mannerisms of motion, and by dress, but these are not to be mistaken for essential hereditary traits. In populations of various parts of Europe many individuals may be found that may as well belong to one part of the continent as to another. There is no truth in the contention so often made that two Englishmen are more alike in bodily form than, let us say, an Englishman and a German. A greater number of forms may be duplicated in the narrower area, but similar forms may be found in all parts of the continent. There is an overlapping of bodily form between the local groups. It is not justifiable to assume that the individuals that do not fit into the ideal local type which we construct from general impressions are foreign elements in the population, that their presence is always due to intermixture with alien types. It is a fundamental characteristic of all local populations that the individuals differ among themselves, and a closer study shows that this is true of animals as well as of men. It is, therefore, not quite proper to speak in these cases of traits that are hereditary in the racial type as a whole, because too many of them occur also in other racial types. Hereditary racial traits should be shared by the whole population so that it is set off against others.

The matter is quite different when individuals are studied as members of their own family lines. Racial heredity implies that there must be a unity of descent, that there must have existed at one time a small number of ancestors of definite bodily form, from whom the present population has descended. It is quite impossible to reconstruct this ancestry through the study of a modern population, but the study of families extending over several generations is often possible. Whenever this study has been undertaken we find that the family lines represented in a single population differ very much among themselves. In isolated communities where the same families have intermarried for generations the differences are less than in larger communities. We may say that every racial group consists of a great many family lines which are distinct in bodily form. Some of these family lines are duplicated in neighboring territories and the more duplication exists the less is it possible to speak of fundamental racial characteristics. These conditions are so manifest in Europe that all we can do is to study the frequency of occurrence of various family lines all over the continent. The differences between the family lines belonging to each larger area are much greater than the differences between the populations as a whole.

Although it is not necessary to consider the great differences in type that occur in a population as due to mixture of different types, it is easy to see that intermingling has played an important part in the history of modern populations. Let us recall to our minds the migrations that occurred in early times in Europe, when the Kelts of Western Europe swept over Italy and eastward to Asia Minor; when the Teutonic tribes migrated from the Black Sea westward into Italy, Spain and even into North Africa; when the Slav expanded northeastward over Russia, and southward into the Balkan Peninsula; when the Moors held a large part of Spain, when Roman and Greek slaves disappeared in the general population, and when Roman colonization affected a large part of the Mediterranean area. It is interesting to note that Spain’s greatness followed the period of greatest race mixture, that its decline set in when the population became stable and immigration stopped. This might give us pause when we speak about the dangers of the intermingling of European types. What is happening in America now is the repetition on a larger scale and in a shorter time of what happened in Europe during the centuries when the people of northern Europe were not yet firmly attached to the soil.

The actual occurrence of intermingling leads us to consider what the biological effect of intermixture of different types may be. Much light has been shed on this question through the intensive study of the phenomena of heredity. It is true we are hampered in the study of heredity in man by the impossibility of experimentation, but much can be learned from observation and through the application of studies of heredity in animals and plants. One fact stands out clearly. When two individuals are mated and there is a very large number of offspring and when furthermore there is no disturbing environmental factor, then the distribution of different forms in the offspring is determined by the genetic characteristics of the parents. What may happen after thousands of generations have passed does not concern us here.

Our previous remarks regarding the characteristics of local types show that matings between individuals essentially different in genetic type must occur in even the most homogeneous population. If it could be shown, as is sometimes claimed, that the progeny of individuals of decidedly distinct proportions of the body would be what has been called disharmonic in character, this would occur with considerable frequency in every population, for we do find individuals, let us say, with large jaws and large teeth and those with small jaws and small teeth. If it is assumed that in the later offspring these conditions might result in a combination of small jaws and large teeth a disharmony would develop. We do not know that this actually occurs. It merely illustrates the line of reasoning. In matings between various European groups these conditions would not be materially changed, although greater differences between parents would be more frequent than in a homogeneous population.

The essential question to be answered is whether we have any evidence that would indicate that matings between individuals of different descent and different type would result in a progeny less vigorous than that of their ancestors. We have not had any opportunity to observe any degeneracy in man as clearly due to this cause. The high nobility of all parts of Europe can be shown to be of very mixed origin. French, German and Italian urban populations are derived from all the distinct European types. It would be difficult to show that any degeneracy that may exist among them is due to an evil effect of intermating. Biological degeneracy is found rather in small districts of intense inbreeding. Here again it is not so much a question of type, but of the presence of pathological conditions in the family strains, for we know of many perfectly healthy and vigorous intensely inbred communities. We find these among the Eskimos and also among many primitive tribes among whom cousin marriages are prescribed by custom.

These remarks do not touch upon the problem of the effect of intermarriages upon bodily form, health and vigor of crosses between races that are biologically more distinct than the types of Europe. It is not quite easy to give absolutely conclusive evidence in regard to this question. Judging merely on the basis of anatomical features and health conditions of mixed populations there does not seem to be any reason to assume unfavorable results, either in the first or in later generations of offspring. The mixed descendants of Europeans and American Indians are taller and more fertile than the pureblood Indians. They are even taller than either parental race. The mixed blood Dutch and Hottentot of South Africa and the Malay mixed bloods of the Island of Kisar are in type intermediate between the two races, and do not exhibit any traits of degeneracy. The populations of the Sudan, mixtures of Mediterranean and Negro types, have always been characterized by great vigor. There is also little doubt that in eastern Russia a considerable infusion of Asiatic blood has occurred. The biological observations on our North American mulattoes do not convince us that there is any deleterious effect of race mixture so far as it is evident in anatomical form and function.

It is also necessary to remember that in varying environment human forms are not absolutely stable, and many of the anatomical traits of the body are subject to a limited amount of change according to climate and conditions of life. We have definite evidence showing changes of bodily size. The stature in European populations has increased materially since the middle of the nineteenth century. War and starvation have left their effects upon the children growing up in the second decade of our century. Proportions of the body change with occupation. The forms of the hand of the laborer and that of the musician reflect their occupations. The changes in head form that have been observed are analogous to those observed in animals under varying conditions of life, among lions born in captivity or among rats fed with different types of diet. The extent to which geographical and social environment may change bodily form is not known, but the influences of outer conditions have to be taken into consideration when comparing different human types.

Selective processes are also at work in changing the character of a population. Differential birth-rate, mortality and migration may bring about changes in the hereditary composition of a group. The range of such changes is limited by the range of variation within the original population. The importance of selection upon the character of a population is easily overestimated. It is true enough that certain defects are transmitted by heredity, but it cannot be proved that a whole population degenerates physically by the numerical increase of degenerates. These always include the physically unfit, and others, the victims of circumstances. The economic depression of our days shows clearly how easily perfectly competent individuals may be brought into conditions of abject poverty and under stresses that only the most vigorous minds can withstand successfully. Equally unjustified is the opinion that war, the struggle between national groups, is a selective process which is necessary to keep mankind on the onward march. Sir Arthur Keith, only a week ago, in his rectoral address at the University of Aberdeen is reported to have said that “Nature keeps her human orchard healthy by pruning and war is her pruning hook.” I do not see how such a statement can be justified in any way. War eliminates the physically strong, war increases all the devastating scourges of mankind such as tuberculosis and genital diseases, war weakens the growing generation. History shows that energetic action of masses may be released not only by war but also by other forces. We may not share the fervor or believe in the stimulating ideals; the important point is to observe that they may arouse the same kind of energy that is released in war. Such a stimulus was the abandonment to religion in the middle ages, such is the abandonment of modern Russian youths to their ideal.

So far we have discussed the effects of heredity, environment and selection upon bodily form. We are not so much concerned with the form of the body as with its functions, for in the life of a nation the activities of the individual count rather than his appearance. There is no doubt in my mind that there is a very definite association between the biological make-up of the individual and the physiological and psychological functioning of his body. The claim that only social and other environmental conditions determine the reactions of the individual disregards the most elementary observations, like differences in heart beat, basal metabolism or gland development; and mental differences in their relation to extreme anatomical disturbances of the nervous system. There are organic reasons why individuals differ in their mental behavior.

But to acknowledge this fact does not mean that all differences of behavior can be adequately explained on a purely anatomical basis. When the human body has reached maturity, its form remains fairly stable until the changes due to increasing age set in. Under normal conditions the form and the chemical constitution of the adult body remain almost stable for a number of years. Not so with bodily functions. The conditions of life vary considerably. Our heart beat is different in sleep and in waking. It depends upon the work we are doing, the altitude in which we live, and upon many other factors. It may, therefore, well be that the same individual under different conditions will show quite different reactions. It is the same with other bodily functions. The action of our digestive tract depends upon the quality and quantity of the food we consume. In short, the physiological reactions of the body are markedly adjusted to conditions of life. Owing to this many individuals of different organic structure when exposed to the same environmental conditions will assume a certain degree of similarity of reaction.

On the whole it is much easier to find decided differences between races in bodily form than in function. It cannot be claimed that the body in all races functions in an identical way, but that kind of overlapping which we observed in form is even more pronounced in function. It is quite impossible to say that, because some physical function, let us say the heart beat, has a certain measure, the individual must be White or Negro—for the same rates are found in both races. A certain basal metabolism does not show that a person is a Japanese or a White, although the averages of all the individuals in the races compared may exhibit differences. Furthermore, the particular function is so markedly modified by the demands made upon the organism that these will make the reactions of the racial groups living under the same conditions markedly alike. Every organ is capable of adjustment to a fairly wide range of conditions, and thus the conditions will determine to a great extent the kind of reaction.

What is true of physiological function is equally true of mental function. There exists an enormous amount of literature dealing with mental characteristics of races. The blond North-Europeans, South Italians, Jews, Negroes, Indians, Chinese have been described as though their mental characteristics were biologically determined. It is true, each population has a certain character that is expressed in its behavior, so that there is a geographical distribution of types of behavior. At the same time we have a geographical distribution of anatomical types, and as a result we find that a selected population can be described as having a certain anatomical type and a certain kind of behavior. This, however, does not justify us in claiming that the anatomical type determines behavior. A great error is committed when we allow ourselves to draw this inference. First of all it would be necessary to prove that the correlation between bodily form and behavior is absolute, that it is valid not only for the selected spot, but for the whole population of the given type, and, conversely, that the same behavior does not occur when the types of bodily build differ. Secondly, it would have to be shown that there is an inner relation between the two phenomena.

I might illustrate this by an example taken from an entirely different field. A particular country has a specific climate and particular geological formation. In the same country is found a certain flora. Nevertheless, the character of soil and climate does not explain the composition of the flora, except in so far as it depends upon these two factors. Its composition depends upon the whole historical evolution of plant forms all over the world. The single fact of an agreement of distribution does not prove a genetic relation between the two sets of observations. Negroes in Africa have long limbs and a certain kind of mental behavior. It does not follow that the long limbs are in any way the cause of their mental behavior. The very point to be proved is assumed as proved in this kind of argumentation.

A scientific solution of this problem requires a different line of approach. Mental activities are functions of the organism. We have seen that physiological functions of the same organism may vary greatly under varying conditions. Is the case of mental reactions different? While the study of cretins and of men of genius shows that biological differences exist which limit the type of individual behavior, this has little bearing upon the masses constituting a population in which great varieties of bodily structure prevail. We have seen that the same physiological functions occur in different races with varying frequency, but that no essential qualitative differences can be established. The question must be asked whether the same conditions prevail in mental life.

If it were possible to subject two populations of different type to the same outer conditions the answer would not be difficult. The obstacle in our way lies in the impossibility of establishing sameness of conditions. Investigators differ fundamentally in their opinion in regard to the question of what constitutes sameness of conditions, and our attention must be directed, therefore, to this question.

If we could show how people of exactly the same biological composition react in different types of environment, much might be gained. It seems to me that the data of history create a strong presumption in favor of material changes of mental behavior among peoples of the same genetic composition. The free and easy English of Elizabethan times contrast forcibly with the prudish Mid-Victorian; the Norse Viking and the modern Norwegian do not impress us as the same; the stern Roman republican and his dissolute descendant of imperial times present striking contrasts.

But we need more tangible evidence. At least in so far as intelligent reaction to simple problems of everyday life is concerned, we may bring forward a considerable amount of experimental evidence that deals with this problem. We do not need to assume that our modern intelligence tests give us a clue to absolutely biologically determined intelligence—whatever that may mean—they certainly do tell us how individuals react to simple, more or less unfamiliar, situations. At a first glance it would seem that very important racial differences are found. I refer to the many comparative tests of the intelligence of individuals of various European types and of Europeans and Negroes. North Europeans tested in our country were found as a whole decidedly superior to South Europeans, Europeans as a whole to Negroes. The question arises, what does this mean? If there is a real difference determined by race, we should find the same kind of difference between these racial types wherever they live. Professor Garth has recently collected the available evidence and reaches the conclusion that it is not possible to prove a difference due to genetic factors, that rather all the available observations may be easily explained as due to differences in social environment. It seems to me the most convincing proof of the correctness of this view has been given by Dr. Klineberg, who examined the various outstanding European types in urban and rural communities in Europe. He found that there is everywhere a marked contrast between rural and urban populations, the city giving considerably better results than the country and that furthermore the various groups do not follow by any means the same order in city and country; that the order rather depends upon social conditions, such as the excellence of the school systems and conflicts between home and school. Still more convincing are his observations on Negroes. He examined a considerable number of Negroes in southern cities who had moved to the city from rural districts. He found that the longer they lived in the city the better the results of the tests came to be, so that Negroes who had lived in the city for six years were far superior to those who had just moved to the city. He found the same result when studying Negroes who had moved from the south to New York, an improvement with the time of residence in New York. This result agrees with Brigham’s findings for Italians who had lived for varying periods in the United States. It has often been claimed, as was done in the beginning by Brigham, that such changes are due to a process of selection, that more poorly endowed individuals have migrated to the country in late years and represent the group that has just come to the city. It would be difficult to maintain this in view of the regularity with which this phenomenon reappears in every test. Still, Dr. Klineberg has also given definite evidence that selection does not account for these differences. He compared the records of the migrating groups with those who remained behind. The records collected in Nashville and Birmingham showed that there is no appreciable difference between the two groups. The migrants were even a little below those who stayed at home. He also found that the migrants who came to New York were slightly inferior to those who remained in the South.

I have given these data in some detail, because they show definitely that cultural environment is a most important factor in determining the results of the so-called intelligence tests. In fact, a careful examination of the tests shows clearly that in none of them has our cultural experience been eliminated. City life and country life, the South and the North present different types of cultural background to which we learn to adapt ourselves, and our reactions are determined by these adaptations, which are often so obscure that they can be detected only by a most intimate knowledge of the conditions of life. We have indications of such adaptations in other cases. It would seem that among the Plains Indians the experience of girls with bead work gives to them a superiority in handling tests based on form. It is highly desirable that the tests should be examined with greatest care in regard to the indirect influence of experience upon the results. I suspect strongly that such influences can always be discovered and that it will be found impossible to construct any test in which this element is so completely eliminated that we could consider the results as an expression of purely biologically determined factors.

It is much more difficult to obtain convincing results in regard to emotional reactions in different races. No satisfactory experimental method has been devised that would answer the crucial question, in how far cultural background and in how far the biological basis of personality is responsible for observed differences. There is no doubt that individuals do differ in this respect on account of their biological constitution. It is very questionable whether the same may be said of races, for in all races we find a wide range of different types of personality. All that we can say with certainty is that the cultural factor is of greatest importance and might well account for all the observed differences, although this does not preclude the possibility of biologically determined differences. The variety of response of groups of the same race but culturally different is so great that it seems likely that any existing biological differences are of minor importance. I can give only a few instances. The North American Indians are reputed as stoic, as ready to endure pain and torture without a murmur. This is true in all those cases in which culture demands repression of emotion. The same Indians, when ill, give in to hopeless depression. Among closely related Indian tribes certain ones are given to ecstatic orgies, while others enjoy a life running in smooth conventional channels. The buffalo hunter was an entirely different personality from the poor Indian who has to rely on government help, or who lives on the proceeds of land rented by his White neighbors. Social workers are familiar with the subtle influence of personal relations that will differentiate the character of members of the same family. Ethnological evidence is all in favor of the assumption that hereditary racial traits are unimportant as compared to cultural conditions. As a matter of fact, ethnological studies do not concern themselves with race as a factor in cultural form. From Waitz on, through Spencer, Tylor, Bastian, to our times, ethnologists have not given serious attention to race, because they find cultural forms distributed regardless of race.

I believe the present state of our knowledge justifies us in saying that, while individuals differ, biological differences between races are small. There is no reason to believe that one race is by nature so much more intelligent, endowed with great will power, or emotionally more stable than another, that the difference would materially influence its culture. Nor is there any good reason to believe that the differences between races are so great that the descendants of mixed marriages would be inferior to their parents. Biologically there is no good reason to object to fairly close inbreeding in healthy groups, nor to intermingling of the principal races.

I have considered so far only the biological side of the problem. In actual life we have to reckon with social settings which have a very real existence, no matter how erroneous the opinions on which they are founded. Among us race antagonism is a fact, and we should try to understand its psychological significance. For this purpose we have to consider the behavior not only of man, but also of animals. Many animals live in societies. It may be a shoal of fish which any individuals of the same species may join, or a swarm of mosquitoes. No social tie is apparent in these groups, but there are others which we may call closed societies that do not permit any outsider to join their group. Packs of dogs and well-organized herds of higher mammals, ants and bees are examples of this kind. In all these groups there is a considerable degree of social solidarity which is expressed particularly by antagonism against any outside group. The troops of monkeys that live in a given territory will not allow another troop to come and join them. The members of a closed animal society are mutually tolerant or even helpful. They repel all outside intruders.

Conditions in primitive society are quite similar. Strict social obligations exist between the members of a tribe, but all outsiders are enemies. Primitive ethics demand self-sacrifice in the group to which the individual belongs, deadly enmity against every outsider. A closed society does not exist without antagonisms against others. Although the degree of antagonism against outsiders has decreased, closed societies continue to exist in our own civilization. The nobility formed a closed society until very recent times. Patricians and plebeians in Rome, Greeks and barbarians, the gangs of our streets, Mohammedan and infidel, and our modern nations are in this sense closed societies that cannot exist without antagonisms. The principles that hold societies together vary enormously, but common to all of them are social obligations within the group, antagonisms against other parallel groups.

Race consciousness and race antipathy differ in one respect from the social groups here enumerated. While in all other human societies there is no external characteristic that helps to assign an individual to his group, here his very appearance singles him out. If the belief should prevail, as it once did, that all red-haired individuals have an undesirable character, they would at once be segregated and no red-haired individual could escape from his class no matter what his personal characteristics might be. The Negro, the East Asiatic or Malay who may at once be recognized by his bodily build is automatically placed in his class and not one of them can escape being excluded from a foreign closed group. The same happens when a group is characterized by dress imposed by circumstances, by choice, or because a dominant group prescribe for them a distinguishing symbol—like the garb of the medieval Jews or the stripes of the convict—so that each individual no matter what his own character may be, is at once assigned to his group and treated accordingly. If racial antipathy were based on innate human traits this would be expressed in interracial sexual aversion. The free intermingling of slave owners with their female slaves and the resulting striking decrease in the number of full-blood Negroes, the progressive development of a half-blood Indian population and the readiness of intermarriage with Indians when economic advantages may be gained by such means, show clearly that there is no biological foundation for race feeling. There is no doubt that the strangeness of an alien racial type does play an important rôle, for the ideal of beauty of the White who grows up in a purely White society is different from that of a Negro. This again is analogous to the feeling of aloofness among groups that are characterized by different dress, different mannerisms of expression of emotion, or by the ideal of bodily strength as against that of refinement of form. The student of race relations must answer the question whether in societies in which different racial types form a socially homogeneous group, a marked race consciousness develops. This question cannot be answered categorically, although interracial conditions in Brazil and the disregard of racial affiliation in the relation between Mohammedans and infidels show that race consciousness may be quite insignificant.

When social divisions follow racial lines, as they do among ourselves, the degree of difference between racial forms is an important element in establishing racial groupings and in creating racial conflicts.

The actual relation is not different from that developing in other cases in which social cleavage develops. In times of intense religious feeling denominational conflicts, in times of war national conflicts take the same course. The individual is merged in his group and not rated according to his personal value.

However, nature is such that constantly new groups are formed in which each individual subordinates himself to the group. He expresses his feeling of solidarity by an idealization of his group and by an emotional desire for its perpetuation. When the groups are denominational, there is strong antagonism against marriages outside of the group. The group must be kept pure, although denomination and descent are in no way related. If the social groups are racial groups we encounter in the same way the desire for racial endogamy in order to maintain racial purity.

On this subject I take issue with Sir Arthur Keith, who in the address already referred to is reported to have said that “race antipathy and race prejudice nature has implanted in you for her own end—the improvement of mankind through racial differentiation.” I challenge him to prove that race antipathy is “implanted by nature” and not the effect of social causes which are active in every closed social group, no matter whether it is racially heterogeneous or homogeneous. The complete lack of sexual antipathy, the weakening of race consciousness in communities in which children grow up as an almost homogeneous group; the occurrence of equally strong antipathies between denominational groups, or between social strata—as witnessed by the Roman patricians and plebeians, the Spartan Lacedaemonians and Helots, the Egyptian castes and some of the Indian castes—all these show that antipathies are social phenomena. If you will, you may call them “implanted by nature,” but only in so far as man is a being living in closed social groups, leaving it entirely indetermined what these social groups may be.

No matter how weak the case for racial purity may be, we understand its social appeal in our society. While the biological reasons that are adduced may not be relevant, a stratification of society in social groups that are racial in character will always lead to racial discrimination. As in all other sharp social groupings the individual is not judged as an individual but as a member of his class. We may be reasonably certain that whenever members of different races form a single social group with strong bonds, racial prejudice and racial antagonisms will come to lose their importance. They may even disappear entirely. As long as we insist on a stratification in racial layers, we shall pay the penalty in the form of interracial struggle. Will it be better for us to continue as we have been doing, or shall we try to recognize the conditions that lead to the fundamental antagonisms that trouble us?

|

Address of the president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Pasadena, June 15. Science, N.S., vol. 74 (1931), pp. 1-8. |

I have been asked to speak on the modern populations of America, and I confess that I feel some hesitation in taking up this important subject. The scientific problems involved are of great and fundamental importance; but unfortunately materials for their discussion have hardly been collected at all, and I do not see any immediate prospect of their being gathered on a scale at all adequate.

We may distinguish three distinct types of populations in modern America. The first type includes those that are entirely or almost entirely descendants of European immigrants, such as the population of the northern United States, of Canada, and of the Argentine; a second type is represented by populations containing a large amount of Indian blood, like those of Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia; and a third type includes populations consisting essentially of mixtures of Negroes and other races. In this last group we may again distinguish between populations in which the mixture is essentially Negro and White and those in which we find a strong mixture of Negro and Indian, or Negro, Indian, and White. Examples of these are the populations of the Southern States, of the West Indies, of some districts of Central and South America, like parts of Brazil, and of certain localities on the west coast of South America.

It will easily be recognized that the mixed populations who are descendants of American Indians and Europeans are found essentially in those large areas in which the aboriginal population at the time of the Conquest was dense. This was the case particularly in Mexico and in the Andean highlands. The extermination of the native population has occurred only in those areas in which at the time of the Conquest the Indian population was very sparse or where a dense population lived in a limited territory, as in the West Indies. The Negro populations occur in all those areas in which there was a long-continued importation of African slaves.

The development of these populations depended to a great extent upon the very fundamental difference in the relations between the Anglo-Saxon European immigrants and the Latin American immigrants. While among the former intermarriages or unions between women of European descent and members of the foreign races were rare, intermixture was not so limited in Latin American countries; and unions between European men and women of foreign races, or of European women and men of foreign races, have always been of more nearly equal frequency. The importance of this difference is great, because in the former case the number of individuals with European blood is constantly increasing, because the children of the women of the White population remain White, while the children of the women of the Negro or Indian population have on the average a considerable amount of infusion of White blood. This must necessarily result in a constant decrease of the relative amount of non-European blood in the total population. This phenomenon may be disturbed to a certain extent by differences in fertility or mortality of the mixed populations, but it is not likely that the total result will be influenced by such differences. In those cases, on the other hand, in which White women marry members of foreign races, or at least half-blood descendants of foreign races, a thorough penetration of the two races must occur; and if marriages in both directions are equally frequent, the result must be a complete permeation of the two types. There is very little doubt that the rapid disappearance of the American Indian in many parts of the United States is due to this peculiar kind of mixture. The women of mixed descent are drawn away from the tribes with a fair degree of rapidity, and merge in the general population; while the men of mixed descent remain in the tribe, and contribute to a continued infusion of White blood among the natives.

The claim has been made, and has constantly been repeated, that mixed races—like the American Mulattoes or the American Mestizos—are inferior in physical and mental qualities, that they inherit all the unfavorable traits of the parental races. So far as I can see, this bold proposition is not based on adequate evidence. As a matter of fact, it would be exceedingly difficult to say at the present time what race is pure and what race is mixed. It is certainly true that in the borderland of the areas inhabited by any of the fundamental races of mankind mixed types do occur, and there is nothing to prove that these types are inferior either physically or mentally. We might adduce, as an example, Japan, a country in which the Malay and the Mongol type come into contact; or the Arab types of North Africa, that are partly of Negro, partly of Mediterranean descent; or the nations of eastern Europe, that contain a considerable admixture of Mongoloid blood. In none of these cases will a careful and conscientious investigator be willing to admit any deteriorating effect of the undoubted mixture of different races. It is exceedingly difficult in all questions of this kind to differentiate with any degree of certainty between social and hereditary causes. On the whole, the half-bloods live under conditions less favorable than the pure parental races; and for this reason the social causes will bring about phenomena of apparent weakness that are erroneously interpreted as due to effects of intermixture. This is particularly true in the case of the Mulatto population of the United States. The Mulatto is found as an important element in many of our American cities where the majority of this group form a poor population, which, on the one hand, is not in a condition of social and economic equality with the Whites, while, on the other hand, the desire for improved social opportunity creates a considerable amount of dissatisfaction. It is not surprising that under these conditions the main characteristics of the group should not be particularly attractive. At the same time the poverty that prevails among many of them, and the lack of sanitary conditions under which they live, give the impression of hereditary weakness.

The few cases in which it has been possible to gather strictly scientific data on the physical characteristics of the half-bloods have rather shown that there may be a certain amount of physical improvement in the mixed race. Thus the investigation of half-blood Indians in the United States which I undertook in 1892 showed conclusively that the physical development of the mixed race, as expressed by their stature, is superior to that of both the White and Indian parents. I also found that the fertility of half-blood women was greater than that of the full-blood Indian women who live practically under the same social conditions. The latter conclusion has been corroborated by a much wider investigation, included in the last Census of the United States. Professor Dixon, under whose auspices the data were collated, not only found that the half-blood women were more fertile than the full-blood women, but he also discovered that the number of surviving children of half-blood women was greater than the number of surviving children of full-blood women. This seems to indicate a greater vigor even more clearly than the data found by a study of the stature of the half-blood race. During the present year I have been able to make an investigation of the population of Puerto Rico; and here a similar phenomenon appears in a comparison between the Mulatto population and the White population. In a study of children it was found that the Mulattoes excel in physical development the children of pure Spanish descent, and that their development is more rapid. Evidently the rapidity of development of the Mulatto, and his better physique, are phenomena that are closely correlated.

A number of tests have been made of the mental conditions of Mulatto children. These, however, I do not consider as convincing, because the differences found are slight, and because, furthermore, the retardation of development due to less favorable social conditions has not sufficiently been taken into account. There is also much doubt in regard to the significance of certain differences in the resistance to pathogenic causes that has been observed in different races. Judging from a general biological point of view, it would seem that an unfavorable effect of mixture of races is very unlikely. The anatomical differences between the races of man that we have to consider here are at best very slight, certainly less than those found in different races of domesticated animals. In the case of domesticated animals, no decrease of vigor has been observed when races are crossed as closely allied as races of man. Since man must be considered anatomically as a highly domesticated species, we may expect the same conditions to prevail, and by analogy there is no reason to suppose any unfavorable effects.

Attention should be called here to a peculiar condition of society in all those regions where the old aboriginal population contributes a large amount to the modern population. In all these cases we observe a continuity of tradition that leads back to pre-Columbian times. It may be that the ancient religious ideas and that much of the oral tradition of the people have been lost and that their place has been taken by ideas imported from Europe. Nevertheless a vast amount of the old customs survives. This may be readily seen by a study of the habitations and of the household utensils in Mexico and in Peru. It is quite obvious that in these cases the ancient tradition survives; and this fact is merely an indication of the tremendous force of conservatism that binds the people of modern times to their past. It is no wonder that in these cases the obstacles to the diffusion of modern ideas are much greater than in those populations that derive their origin entirely from European sources. This is so much more the case, since the European immigrant breaks completely with his past, and develops in a new environment and according to new standards of thought.

The investigation of the ideas and beliefs of the American Negroes throws an interesting side-light on these conditions. Unfortunately this subject has received very slight attention, and it is hardly possible to state definitely what the conditions are in various parts of the continent. It is quite clear, however, that the Negroes, owing to their segregation, have retained much of what they brought from Africa. In this case there is no continuity in the material life, because the houses, household utensils, and other objects are all derived from European sources, while many of the old tales and old religious ideas seem to survive, much modified, however, by American conditions. Owing to the fact that the coast tribes of Africa have been long under the influence of Portuguese civilization, a certain assimilation of Negro ideas had developed; and in all probability this accounts for the similarity of ideas found among American Negroes and Indians of Latin America, so far as these have adopted ideas imported by Spaniards and Portuguese of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Another question relating to the physical type of the mixed populations relates to the question of how far a new type results from their intermingling. Of recent years there has been much discussion in regard to this problem. Galton and his adherents maintain that in a mixture of types a new intermediate type will develop analogous to the appearance of the mule as a result of mixture between horse and donkey. Other investigators, following the important observations of Mendel and his successors, claim that no permanent new type develops, but that the so-called “unit” characters of the parents will be segregated in the mixed population. Assuming, for instance, the blue eye of the North European to be a “unit” character, it is assumed that in the mixed type there will always remain a certain group with blue eyes. More specifically it is claimed that among the descendants of couples in which one parent has blue eyes, the other pure brown eyes, one-fourth of the total number from the second generation on will have blue eyes, while the rest will have brown eyes. In order to avoid technicalities, we might perhaps say that in these cases there must be a certain degree of alternating inheritance, in so far as in a mixed population some individuals will resemble in their traits the one parental race, while others will resemble the other. Some investigators claim that the existence of this type of inheritance—so-called “Mendelian” inheritance—has been definitely proved to exist in man.

It is hardly possible at the present time to answer this important problem with any degree of definiteness, although in regard to a number of traits sufficient evidence is available. I pointed out before that in the case of stature the half-blood shows a tendency to exceed both parental types; in other words, that a new distinctive form develops. On the other hand, the investigation of eye-color has shown that while intermediate eye-colors do occur, there is a decided tendency for a number of individuals to reproduce either the blue eyes of northern Europe or the very dark eyes of other races. In regard to skin-color the evidence is not clear. A certain permanence of type has also been found in the head form. Some types of man may be characterized by the ratio of the longitudinal to the transversal diameter of the head. Sometimes both are not very different, while in other cases the head is very narrow and at the same time very long. It has been found that when two types intermingle in which the parental races show material differences in head form, then a great variety of head forms will occur among the descendants, indicating a tendency to revert to the parental types. Whether or not the classical ratios of Mendelian inheritance prevail is a question that it is quite impossible to answer. On the whole, it seems much more likely that we have varying types of alternating inheritance rather than true Mendelian forms.

If further investigation should show that the tendency to such alternating inheritance is found in mixed types throughout, and that the different features belonging to the distinctive parental types have only slight degrees of correlation, it would follow that in a mixed type we may expect the occurrence of a great variety of combinations of parental types; and we may expect, perhaps, a certain loosening of those correlations that are characteristic for the parental races. This question, however, has never been investigated, and cannot be answered with any degree of certainty.

These questions have also a bearing upon the characteristics of the populations of pure European descent that are developing in our country. In earlier times the provenience of the settlers in each particular area was fairly uniform. In the United States we find settlers from England; in the Argentine, those from Spain; but the rapid increase of population in Europe, and the attractiveness of economical conditions in America, have brought it about that the sources of European immigration have become much wider. In the Argentine Republic we find an immigration coming principally from the shores of the Mediterranean. The modern population of the United States is drawn from all parts of Europe, the most recent influx being principally from southeastern, southern, and eastern Europe. The racial composition of the population of Europe is not by any means uniform; but we find distinctive local types inhabiting the various parts of the continent. The differences between a dark-eyed, black-haired, swarthy South Italian, and a blond, tall, blue-eyed Scandinavian and a short-headed, gray-eyed, tall Servian, are certainly most striking. This fact has led to the assertion that nothing like the modern intermixture of European types has ever occurred in the past in any part of Europe.

Attention should be called here to a peculiar difference between the composition of our American population and that of European populations. After individual land-tenure had developed, and agriculture had become the basis of life of all European peoples, a remarkable permanence of habitat developed in all parts of Europe. In place of the waves of migration that marked the end of antiquity, a local development of small village communities set in, which, after they were once established, came to be exceedingly permanent. The members of these communities were only slightly increased from the outside, and thus a period of inbreeding set in that is equaled only by the amount of inbreeding characteristic of small isolated primitive tribes. It is difficult to obtain exact information in regard to this process; but the investigation of genealogies of a few European communities shows that it has been very marked. It is therefore clear that when we compare, let me say, the population of a small Spanish village and that of a South Italian village, we may find in both communities what appears to the observer as the same type; but we find at the same time that the actual lines of descent of these two groups have been quite distinct for many generations. A peculiar result is found wherever this type of inbreeding occurs. Since all the families are interrelated, it is clear that all the families are very much alike, and that practically any family may be selected and considered as the type of the population that is being investigated. Wherever these conditions do not prevail, and where the ancestry of the various parts of the population is quite distinct, a single family can never be considered as representative of the whole population, and we may expect considerable differences to occur between the family lines. This coming together of distinct lines is characteristic of all the industrial districts of Europe and also of the populations of European descent in America. Thus in the Argentine Republic the people of Spanish and of Italian communities will be brought together. In the United States we find side by side families of English, Irish, French, Spanish, German, Russian, and Italian descent, each of which represents the type of the locality from which it comes. In other words, the family lines composing American populations are much more diverse than those found in the rural communities of Europe.

From a biological point of view there is little doubt that this condition must have an effect upon the physical characteristics of the whole population. Observations are not available, except those bearing upon the relation of sexes in the Argentine Republic. According to the last Argentine census, it has been found that the relation of sexes of children found in families of pure Italian or pure Argentine descent shows considerable differences when compared with that found in families of mixed Italo-Spanish descent, and it may very well be that this has to do with the disturbances of the lines of descent which we have just discussed.

No investigations are available on the physical characteristics of individuals of mixed European descent. All we know is that the alternating inheritance referred to before may be observed also in the descendants of a single people. Thus, for instance, it has been shown that when a long-headed Russian Jew marries a short-headed Russian Jewess, the children resemble in part the father, in part the mother, so that here also a certain reversion of type may be noticed. It has also been found that the laws of inheritance of eye-color are similar to those referred to before. There is therefore every reason to assume that the same laws of inheritance prevail in a mixture of European peoples that have been observed in a mixture of different races.

A word should be said in regard to the claim that the mixture of European types that is characteristic of the population of modern America is of a unique character. The events that occurred in prehistoric Europe do not favor this assumption, because the European continent at that time was the scene of constant migration and of constant intermingling of different peoples. The contrast between medieval conditions and ancient conditions appears, for instance, very clearly in Spain. The oldest inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula of which we know were overlaid successively by Phenicians, Romans, Kelts, Teutonic tribes, and Moorish people from northern Africa, which resulted in an enormous infusion of blood from all parts of Europe. With the Spanish victories over the Moors and the driving away of the Jews, a period of inbreeding set in which has lasted up to the present time. Similar conditions obtain in eastern Europe, where waves of migrations of Slavic, Teutonic, Finnish and Mongol peoples may be traced, each of which represented a certain definite local type. In short, the whole early history of Europe is one continued series of shifts of populations, that must have resulted in an enormous mixture of all the different types of the continent.

The important question arises whether the types that come to America remain stable and retain their former characteristics. A number of years ago I investigated this question, and reached the conclusion that a number of definite, although slight, changes are taking place; more particularly, that under American geographical and social conditions the width of the face decreases, and the head form undergoes certain slight changes. My observations are corroborated by the evidence that may be obtained from studies of European city populations. The differences in social environment there are probably the same as those that I have observed in the city of New York; and the observations also indicate a certain difference between the city population and the country population which cannot be explained by mixture or by selection.

Quite recently I investigated this question in Puerto Rico, and found that the type of the modern population does not conform to any of the ancestral types. The population is derived very largely from Spanish sources, so much so that among the individuals whom I measured a large percentage were sons of Spanish-born fathers. Besides this, we find a considerable infusion of Negro blood, and I presume also a certain survival of Indian blood. The ancestral types, except the Indians, are decidedly long-headed. The Indian blood cannot be very considerable; nevertheless we find that the Puerto Ricans of today are as short-headed as the average of the French of the Auvergne. We may therefore conclude that the movement of populations from Europe to our continent is accompanied by certain changes of type, the extent of which cannot be definitely determined at the present time.

I cannot conclude my remarks without at least a brief reference to the modern endeavors to improve the physical type of the people. It has been claimed that the congestion in modern cities and other causes are bringing about a gradual degeneration of our race, which advocates of eugenics desire to counteract by adequate legislative measures. It is certainly right to try to check the spread of hereditary defects by such measures, but the movement as it is now conceived is not free of serious dangers. First of all, it would seem that the fundamental thesis of the degeneracy of our population has never been proved. Our statistics permit us to count the number of defective individuals, which of course appears to increase with the rigidity of examination. On the other hand, our statistics do not allow us to count the individuals of unusual physical or mental development. It is obvious that, even if the method of counting should remain the same, there would be an apparent increase in the number of defectives if the variability of the total population should increase; in other words, if not all should conform to a standard, but a considerable number should be inordinately gifted, another number inordinately deficient. This would not necessarily mean a degeneration of the population, but would merely be an expression of increased variability. More serious is the question whether the principles of eugenics conform to the natural development of the human species. The fundamental motive that prompts us to advocate eugenic measures is perhaps not so much the idea of increasing human efficiency as rather to eliminate human suffering. The humanitarian idea of the elimination of suffering, which conforms so well with our sentiments, seems, however, opposed to the conditions under which species thrive. What is an inconvenience today will be suffering tomorrow; and the effect of an exaggerated humanitarianism may be to make mankind so sensitive to suffering that the very roots of its existence will be endangered. This consideration ought to receive the most careful attention of those who try to predetermine the development of our populations by legislative devices.

|

From Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Americanists, Washington, December, 1915 (Washington, D. C., 1917), pp. 569-575. |

The White population of the United States differs from that of Europe not so much in character as in the mode of assemblage of its component elements. The important theoretical and practical problems that arise in a study of the biological characteristics of our population relate largely to the effects of the recent rapid migrations of the diverse types of Europeans. The problem is further complicated by the presence of a large Negro population, of small remnants of Indian aborigines, and by a slight influx of Asiatics.