* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: The Canadian Settler's Guide

Date of first publication: 1857

Author: Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899)

Date first posted: December 22 2014

Date last updated: December 22 2014

Faded Page eBook #20141247

This eBook was produced by: Marcia Brooks, David Edwards, "goofball" & the Online Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

(This file was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Book Search project.)

Entered according to the Act of the Provincial Legislature, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-five, in the Office of the Registrar of the Province of Canada, and at Stationers Hall, London.

The value attached to this little work may be estimated in some degree by its having already reached a Seventh Edition.

The testimony borne to its worth and utility to actual and intending Settlers, by persons so well entitled to give an opinion of its merits as William Hutton, Esq., Secretary to the Board of Agriculture and statistics; Frederic Widder, Esq., Resident Commissioner of the Canada Company, and A. O. Buchanan and A. B. Hawke, Esqs., The Government Emigration-Agents at Quebec and Toronto, has doubtless given it an importance which it otherwise might not have attained.

The Appendix has been added by the Publisher, who has collated his information from the most authentic and reliable sources.

The matter in the other portion of the book is written by Mrs. Traill, after a residence of twenty-five years in the Colony, a considerable portion of which has been in those "Backwoods of Canada," so vivid and interesting a description of which she gave to the public through the columns of Knight's volumes.

The growing interest felt in Canadian matters at home, and the prospect of an extensive Emigration to this Province in the approaching year, have caused a large demand for the work from Great Britain and other parts of Europe; with a view therefore to make it more useful and acceptable, a very large and valuable addition has been made to it, selected from the works and "endorsed" by the opinions of some of the most eminent authorities in Canada.

The addition made consists of the following articles:

1. The Future of Western Canada.

2. The Railway Policy of Canada.

5. Instructions to Emigrants as to Outfit, Choice of a Vessel, &c., &c. by Vere Foster, Esq.

6. A Description of the Lands in the Free Grants by E. Perry, Esq., Resident Agent at Kaladar.

These various documents comprise an amount of information, the result of actual experience, and bearing the stamp of official authority, upon which the utmost reliance may be placed; and they are published with a view to the instruction and guidance of Settlers of all classes who may contemplate a residence in this thriving Colony, whose onward progress exceeds that of any other dependency of the British Crown.

It is proper to state that the Statistical Information given herein comes up to the last period to which official returns have been rendered, but the progress made in the five years which have elapsed since that time very far exceeds any similar period in every particular.

Then no Railroads were in progress, now there are fifteen hundred miles in full operation, extending from Portland to the extreme western boundary of Upper Canada!

To this brief notice the Publisher will only add his earnest advice and decided opinion that future Emigrants should, on every account, avail themselves of the facilities for reaching Canada by the Canadian Screw-Steamers which hereafter will regularly sail from British Ports to Portland, Quebec or Montreal, from all of which places access can be had to every part of the Province by the Grand Trunk Railway, by the Directors and Officers of which every possible facility will be given for their cheap and expeditious transit to their various destinations, every attention paid to their comforts, and the most reliable information afforded.

The Publisher has carefully abstained from giving any account of the Province more favorable than the one borne out by official returns as to fertility and climate.

The Table of wages inserted in the appendix is rather under than over the prices now readily obtainable.

The prices of labour and provisions are all reckoned in Canada currency. A deduction of one-fifth brings them all as nearly as possible into sterling value.

Toronto, C. W., 1st January, 1857.

N.B. The tariff printed in the Appendix has been considerably modified,

and is not to be relied upon at the present moment.

| Dedication | iv |

| Preface | ix |

| Introductory Remarks | 13 |

| ———— | |

| Ague | 197 |

| Apples, Pears, Cherries | 67, 79 |

| Beer | 136 |

| Bees | 201 |

| Borrowing | 38 |

| Bread-making, &c., &c. | 91 |

| Buckwheat | 109 |

| Cakes, &c. | 101 |

| Carpets, Home-made | 177 |

| Canada, Letters from | 214 |

| Candle-Making, | 168 |

| Cheese do. | 185 |

| Coffee and Tea, Substitutes for | 133 |

| Corn, Indian | 112 |

| Curing of Fish | 158 |

| " Meat | 148 |

| Dairy | 180 |

| Dysentery | 199 |

| Dying Wool, &c. | 172 |

| Fish | 158 |

| Fire | 194 |

| Fruits | 79 |

| Game | 153 |

| Gardening | 60 |

| Knitting | 178 |

| Land, Value of | 49 |

| Letters From Canada | 214 |

| Miscellaneous Matter | 221 |

| Months, Summary of operations in | 202 to 213 |

| Oatmeal | 110 |

| Peaches | 87 |

| Poetry | 22 |

| Poultry | 190 |

| Potatoes | 122 |

| Pumpkins | 127 |

| Property, Security of | 56 |

| Productions, Natural, of Canada | 202 |

| Rice, Indian | 107 |

| Settlement, Description of New | 51 |

| Ship Stores | 41 |

| Soap-Making | 163 |

| Sugar, Making of Maple | 141 |

| Vegetables | 62, 130 |

| Venison | 151 |

| Wild Fruits | 80 |

| Wool | 171 |

| Table to calculate equivalent value of Currency and Cents | 4 | |

| " " Sterling Money and Currency | 5 | |

| " Land Measure | 9 | |

| " Short Weight into Long Weight and Long Weight into Short | 11 | |

| " To buy and sell by the Great Hundred | 11 | |

| " Wages, to Calculate | 12 | |

| " Income and Expenses | 30 | |

| " Length and Breadth of Imperial Acre, | 9 | |

| " Interest Tables | 12 | |

| " Useful Information to Farmers | 7, 13 | |

| Emigrants, Information as to transmitting Moneys to Europe safely | 36 | |

| Crown Lands, Conditions to be Observed | 36 | |

| Deaths and Census of Deaths in the Canadas in 1853 | 12 | |

| Canada, Condition of, Collated from Census Returns | 14 to 24 | |

| Deaths, Comparative Ratio of, in the Canadas and United States | 27 | |

| Wheat, Average Produce of in ditto | 29 | |

| Products Agricultural, Comparison of in ditto | 40 | |

| Temperature and Climate:— | ||

| Comparative Meteorology in Toronto, U. C., and High-field House, Nottingham, England | 37 | |

| Comparative Mean Temperature for the year and different seasons, and also the extremes of Temperature and climatic differences in various parts of Europe and America | 10, 38 | |

| Tariff:— | ||

| New, of Duties, to come into operation first of April, 1855 | 31 | |

| Postage:— | ||

| New Book Regulations | 40 | |

Among the many books that have been written for the instruction of the Canadian emigrant, there are none exclusively devoted for the use of the wives and daughters of the future settler, who for the most part, possess but a very vague idea of the particular duties which they are destined to undertake, and are often totally unprepared to meet the emergencies of their new mode of life.

As a general thing they are told that they must prepare their minds for some hardships and privations, and that they will have to exert themselves in a variety of ways to which they have hitherto been strangers; but the exact nature of that work, and how it is to be performed, is left untold. The consequence of this is, that the females have everything to learn, with few opportunities of acquiring the requisite knowledge, which is often obtained under circumstances, and in situations the most discouraging; while their hearts are yet filled with natural yearnings after the land of their birth, (dear even to the poorest emigrant), with grief for the friends of their early days, and while every object in this new country is strange to them. Disheartened by repeated failures, unused to the expedients which the older inhabitants adopt in any case of difficulty, repining and disgust take the place of cheerful activity; troubles increase, and the power to overcome them decreases; domestic happiness disappears. The woman toils [Pg x] on heart-sick and pining for the home she left behind her. The husband reproaches his broken-hearted partner, and both blame the Colony for the failure of the individual.

Having myself suffered from the disadvantage of acquiring all my knowledge of Canadian housekeeping by personal experience, and having heard other females similarly situated lament the want of some simple useful book to give them an insight into the customs and occupations incidental to a Canadian settler's life, I have taken upon me to endeavor to supply this want, and have with much labour collected such useful matter as I thought best calculated to afford the instruction required.

As even the materials differ, and the method of preparing food varies greatly between the colony and the Mother-country, I have given in this little book the most approved recipes for cooking certain dishes, the usual mode of manufacturing maple-sugar, soap, candles, bread and other articles of household expenditure; in short, whatever subject is in any way connected with the management of a Canadian settler's house, either as regards economy or profit, I have introduced into the work for the benefit of the future settler's wife and family.

As this little work has been written for all classes, and more particularly for the wives and daughters of the small farmers, and a part of it is also addressed to the wives of the labourer and mechanics, I aimed at no beauty of style. It was not written with the intention of amusing, but simply of instructing and advising.

[Pg xi] I might have offered my female friends a work of fiction or of amusing facts, into which it would have been an easy matter to have interwoven a mass of personal adventure, with useful information drawn from my own experience during twenty-two years sojourn in the Colony; but I well knew that knowledge conveyed through such a medium is seldom attended with practical results; it is indeed something like searching through a bushel of chaff to discover a few solitary grains of wheat. I therefore preferred collating my instruction into the more homely but satisfactory form of a Manual of Canadian housewifery, well contented to abandon the paths of literary fame, if I could render a solid benefit to those of my own sex who through duty or necessity are about to become sojourners in the Western Wilderness.

It is now twenty years ago since I wrote a work with the view of preparing females of my own class more particularly, for the changes that awaited them in the life of a Canadian emigrant's wife. This book was entitled "Letters from the Backwoods of Canada," and made one of the volumes in Knight's "Library of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge," and was, I believe, well received by the public; but as I had then been but a short time resident in the country, it was necessarily deficient in many points of knowledge which I have since become aware were essential for the instruction of the emigrant's wife. These deficiencies I have endeavoured to supply in the present work, and must here acknowledge with thanks the assistance that I have received from several ladies of my acquaintance, who have kindly supplied me with hints from their own experience on various matters.

To Mr. W. McKyes, Mrs. McKyes and Miss McKyes I am largely indebted for much useful information; also to Mrs. Stewart of Auburn, Douro, and her kind family; and to Misses A. and M. Ferguson; with many others, by whose instruction I have been largely benefitted; and take the present opportunity of publicly acknowledging my obligations.

Hoping that my little volume may prove a useful guide, I dedicate it with heartfelt good wishes to the Wives and Daughters of the

Before the master of the household fully decides upon taking so important a step as leaving his native land to become a settler in Canada, let him first commune with himself and ask the important question, Have I sufficient energy of character to enable me to conform to the changes that may await me in my new mode of life?—Let him next consider the capabilities of his partner; her health and general temper; for a sickly, peevish, discontented person will make but a poor settler's wife in a country where cheerfulness of mind and activity of body are very essential to the prosperity of the household.

In Canada persevering energy and industry, with sobriety, will overcome all obstacles, and in time will place the very poorest family in a position of substantial comfort that no personal exertions alone could have procured for them elsewhere.

To the indolent or to the intemperate man Canada offers no such promise; but where is the country in which such a person will thrive or grow wealthy? He has not the elements of success within him.—It is in vain for such a one to cross the Atlantic; for he will bear with him that fatal enemy which kept him poor at home. The active, hard-working inhabitants who are earning their bread honestly by the sweat of their brow, or by the exertion of mental power, have no sympathy with such men. Canada is not the land for the idle sensualist. He must forsake the error of his ways at once, or he will sink into ruin here as he would have done had he staid in the old country. But it is not for such persons that our book is intended.

As soon as the fitness of emigrating to Canada has been fully decided upon, let the females of the family ask God's blessing upon their undertaking; ever bearing in mind that "unless the Lord build the house, [Pg 14] their labour is but lost that build it; unless the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain." In all their trials let them look to Him who can bring all things to pass in His good time, and who can guard them from every peril, if they will only believe in His promises, and commit their ways to Him.

As soon, then, as the resolution to emigrate has been fixed, let the females of the house make up their minds to take a cheerful and active part in the work of preparation. Let them at once cast aside all vain opposition and selfish regrets, and hopefully look to their future country as to a land of promise, soberly and quietly turning their attention to making the necessary arrangements for the important change that is before them.

Let them remember that all practical knowledge is highly valuable in the land to which they are going. An acquaintance with the homely art of baking and making bread, which most servants and small housekeepers know how to practice, but which many young females that live in large towns and cities where the baker supplies the bread to the family, do not, is necessary to be acquired.

Cooking, curing meat, making butter and cheese, knitting, dress-making and tailoring—for most of the country-people here make the everyday clothing of their husbands, brothers or sons—are good to be learned. By ripping to pieces any well-fitting old garment, a suitable pattern may be obtained of men's clothes; and many a fair hand I have seen occupied in making garments of this description. For a quarter of a dollar, 1s. 3d., a tailor will cut out a pair of fine cloth trowsers; for a coat they charge more; but a good cloth is always better to have made up by a regular tailor: loose summer coats may be made at home, but may be bought cheap, ready-made, in the stores.

My female friends must bear in mind that it is one of the settler's great objects to make as little outlay of money as possible. I allude to such as come out to Canada with very little available capital excepting what arises from the actual labour of their own hands, by which they must realize the means of paying for their land or the rental of a farm. Everything that is done in the house by the hands of the family, is so much saved or so much earned towards the paying [Pg 15] for the land or building houses and barns, buying stock or carrying on the necessary improvements on the place: the sooner this great object is accomplished, the sooner will the settler and his family realize the comfort of feeling themselves independent.

The necessity of becoming acquainted with the common branches of household work may not at first be quite agreeable to such as have been unaccustomed to take an active part in the duties of the house. Though their position in society may have been such as to exempt them from what they consider menial occupations, still they will be wise to lay aside their pride and refinement, and apply themselves practically to the acquirement of such useful matters as those I have named—if they are destined to a life in a colony—even though their friends may be so well off as to have it in their power to keep servants, and live in ease and comfort. But if they live in a country place, they may be left without the assistance of a female-servant in the house, a contingency which has often happened from sudden illness, a servant's parents sending for them home, which they will often do without consulting either your convenience or their daughter's wishes, or some act on the part of the servant may induce her to be discharged before her place can be filled; in such an emergency the settler's wife may find herself greatly at a loss, without some knowledge of what her family requires at her hands. I have before now seen a ragged Irish boy called in from the clearing by his lady-mistress, to assist her in the mystery of making a loaf of bread, and teaching her how to bake it in the bake-kettle. She had all the requisite materials, but was ignorant of the simple practical art of making bread.

Another who knew quite well how to make a loaf and bake it too, yet knew nothing of the art of making yeast to raise it with, and so the family lived upon unleavened cakes, or dampers, as the Australians call them, till they were heartily tired of them: at last a settler's wife calling in to rest herself, and seeing the flat cakes baking, asked the servant why they did not make raised bread: "Because we have no yeast, and do not know how to make any here in these horrible backwoods," was the girl's reply. The neighbour, I dare say, was astonished at the ignorance of both mistress and maid; but she gave them some hops and a little barm, and told the girl how to [Pg 16] make the yeast called hop-rising; and this valuable piece of knowledge stood them in good stead: from that time they were able to make light bread; the girl shrewdly remarking to her mistress, that a little help was worth a deal of pity. A few simple directions for making barm as it is here practiced, would have obviated the difficulty at first. As this is one of the very first things that the housewife has to attend to in the cooking department, I have placed the raising and making of bread at the beginning of the work. The making and baking of really good household bread is a thing of the greatest consequence to the health and comfort of a family.

As the young learn more quickly than the old, I would advise the daughters of the intending emigrant to acquire whatever useful arts they think likely to prove serviceable to them in their new country. Instead of suffering a false pride to stand in their way of acquiring practical household knowledge, let it be their pride—their noble, honest pride—to fit themselves for the state which they will be called upon to fill—a part in the active drama of life; to put in practice that which they learned to repeat with their lips in childhood as a portion of the catechism, "To do my duty in that state of life, unto which it may please God to call me." Let them earnestly believe that it is by the will of God that they are called to share the fortunes of their parents in the land they have chosen, and that as that is the state of life they are called to by his will, they are bound to strive to do their duty in it with cheerfulness.

There should therefore be no wavering on their part; no yielding to prejudices and pride. Old things are passed away. The greatest heroine in life is she who knowing her duty, resolves not only to do it, but to do it to the best of her abilities, with heart and mind bent upon the work.

I address this passage more especially to the daughters of the emigrant, for to them belongs the task of cheering and upholding their mother in the trials that may await her. It is often in consideration of the future welfare of their children, that the parents are, after many painful struggles, induced to quit the land of their birth and the home that was endeared to them alike by their cares and their joys; and though the children may not know this to be the [Pg 17] main-spring that urges them to make the sacrifice, in most cases it is so; and this consideration should have its full weight, and induce the children to do all in their power to repay their parents for the love that urges them to such a decision.

The young learn to conform more readily to change of country than the old. Novelty has for them a great charm: and then hope is more lively in the young heart than in the old. To them a field of healthy enterprise is open, which they have only to enter upon with a cheerful heart and plenty of determination, and they will hardly fail of reaching a respectable state of independence.

The wives and daughters of the small farmers and of the working class, should feel the difficulties of a settler's life far less keenly than any other, as their habits and general knowledge of rural affairs have fitted them for the active labours that may fall to their lot in Canada. Though much that they have to perform will be new to them, it will only be the manner of doing it, and the difference of some of the materials that they will have to make use of: enured from childhood to toil, they may soon learn to conform to their change of life. The position of servants is much improved in one respect: their services are more valuable in a country where there is less competition among the working class. They can soon save enough to be independent. They have the cheering prospect always before them: It depends upon ourselves to better our own condition. In this country honest industry always commands respect: by it we can in time raise ourselves, and no one can keep us down.

Yet I have observed with much surprize that there is no class of emigrants more discontented than the wives and daughters of those men who were accustomed to earn their bread by the severest toil, in which they too were by necessity obliged to share, often with patience and cheerfulness under privations the most heartbreaking, with no hope of amendment, no refuge but the grave from poverty and all its miseries. Surely to persons thus situated, the change of country should be regarded with hopeful feelings; seeing that it opens a gate which leads from poverty to independence, from present misery to future comfort.

[Pg 18] At first the strangeness of all things around them, the loss of familiar faces and familiar objects, and the want of all their little household conveniences, are sensibly felt; and these things make them uncomfortable and peevish: but a little reasoning with themselves would show that such inconveniences belong to the nature of their new position, and that a little time will do away with the evil they complain of.

After a while new feelings, new attachments to persons and things, come to fill up the void: they begin to take an interest in the new duties that are before them, and by degrees conform to the change; and an era in their lives commences, which is the beginning to them of a better and more prosperous state of things.

It frequently happens that before the poor emigrant can settle upon land of his own, he is obliged to send the older children out to service. Perhaps he gets employment for himself and his wife, on some farm, where they can manage to keep the younger members of the family with them, if there is a small house or shanty convenient, on or near the farm on which they are hired. Sometimes a farmer can get a small farm on shares; but it is seldom a satisfactory mode of rental, and often ends in disagreement. As no man can serve two masters, neither can one farm support two, unless both parties are which rarely happens, quite disinterested and free from selfishness, each exacting no more than his due. It is seldom these partnerships turn out well.

There is an error which female servants are very apt to fall into in this country, which as a true friend, I would guard them against committing. This is adopting a free and easy manner, often bordering upon impertinence, towards their employers. They are apt to think that because they are entitled to a higher rate of wages, they are not bound to render their mistresses the same respect of manners as was usual in the old country. Now, as they receive more, they ought not to be less thankful to those who pay them well, and should be equally zealous in doing their duty. They should bear in mind that they are commanded to render "honor to whom honor is due." A female servant in Canada whose manners are respectful [Pg 19] and well-behaved, will always be treated with consideration and even with affection. After all, good-breeding is as charming a trait in a servant as it is in a lady. Were there more of that kindly feeling existing between the upper and lower classes, both parties would be benefitted, and a bond of union established, which would extend beyond the duration of a few months or a few years, and be continued through life: how much more satisfactory than that unloving strife where the mistress is haughty and the servant insolent.

But while I would recommend respect and obedience on the part of the servant, to her employer I would say, treat your servants with consideration: if you respect her she will also respect you; if she does her duty, she is inferior to no one living as a member of the great human family. The same Lord who says by the mouth of his apostle, "Servants obey your masters," has also added, "and ye masters do ye also the same, forbearing threatening; knowing that your master also is in heaven, and that with him there is no respect of persons."

Your servants as long as they are with you, are of your household, and should be so treated that they should learn to look up to you in love as well as reverence.

If they are new comers to Canada, they have everything to learn; and will of course feel strange and awkward to the ways of the colony, and require to be patiently dealt with. They may have their regrets and sorrows yet rankling in their hearts for those dear friends they have left behind them, and require kindness and sympathy.—Remember that you also are a stranger and sojourner in a strange land, and should feel for them and bear with them as becomes Christians.

Servants in Canada are seldom hired excepting by the month.—The female servant by the full calendar month; the men and boys' month is four weeks only. From three to four dollars a month is the usual wages given to female servants; and two, and two dollars and a half, to girls of fourteen and sixteen years of age, unless they are very small, and very ignorant of the work of the country; then less is given. Indeed, if a young girl were to give her services for a [Pg 20] month or two, with a good clever mistress, for her board alone, she would be the gainer by the bargain, in the useful knowledge which she would acquire, and which would enable her to take a better place, and command higher wages. It is a common error in girls coming direct from the old country, and who have all Canada's ways to learn, to ask the highest rate of wages, expecting the same as those who are twice as efficient. This is not reasonable; and if the demand be yielded to from necessity, there is seldom much satisfaction or harmony, both parties being respectively discontented with the other. The one gives too much, the other does too little in return for high wages.

Very little if any alteration has taken place nominally in the rate of servants' wages during twenty-one years that I have lived in Canada, but a great increase in point of fact.[1] Twenty years ago the servant-girl gave from 1s. 6d. to 2s. 6d. a yard for cotton prints, 10s. and 12s. a pair for very coarse shoes and boots: common white calico was 1s. and 1s. 3d. per yard, and other articles of clothing in proportion. Now she can buy good fast prints at 9d. and 10d., and some as low as 7½d. and 8d. per yard, calicoes and factory cottons from 4½d. to 9d. or 10d.; shoes, light American-made and very pretty, from 4s. 6d. to 7s. 6d., and those made to order 6s. 3d. to 7s. 6d.; boots 10s.; straw bonnets from 1s. 6d., coarse beehive plat, to such as are very tasteful and elegant in shape and quality, of the most delicate fancy chips and straws, proportionably cheap.

Thus while her wages remain the same, her outlay is decreased nearly one-half.

Ribbons and light fancy goods are still much higher in price than they are in the old country; so are stuffs and merinos. A very poor, thin Coburg cloth, or Orleans, fetches 1s. or 1s. 3d. per yard; mousselin de laines vary from 9d. to 1s. 6d. Probably the time will come when woollen goods will be manufactured in the colony; but the time for that is not yet at hand. The country flannel, home-spun, home-dyed and sometimes home-woven, is the sort of material worn in the house by the farmer's family when at work. Nothing can be more suitable to the climate, and the labours of a Canadian settler's wife or daughter, than gowns made of this country flannel: it is very [Pg 21] durable, lasting often two or three seasons. When worn out as a decent working dress, it makes good sleigh-quilts for travelling, or can be cut up into rag-carpets, for a description of which see the article—Rag-Carpets: and for instructions in dyeing the wool or yarn for the flannel see Dyeing. I have been thus minute in naming the prices of women's wearing apparel, that the careful wife may be enabled to calculate the expediency of purchasing a stock of clothes, before leaving home, or waiting till she arrives in Canada, to make her needful purchases. To such as can prudently spare a small sum for buying clothes, I may point out a few purchases that would be made more advantageously in England or Scotland than in Canada: 1st. A stock, say two pairs a piece for each person, of good shoes.—The leather here is not nearly so durable as what is prepared at home, and consequently the shoes wear out much sooner, where the roads are rough and the work hard. No one need encumber themselves with clogs or pattens: the rough roads render them worse than useless, even dangerous, in the spring and fall, the only wet seasons: in winter the snow clogs them up, and you could not walk ten yards in them; and in summer there is no need of them: buy shoes instead; or for winter wear, a good pair of duffle boots, the sole overlaid with india-rubber or gutta percha.

India-rubber boots and over-shoes can be bought from 4s. to 7s. 6d., if extra good, and lined with fur or fine flannel. Gentlemen's boots, long or short, can be had also, but I do not know at what cost. Old women's list shoes are good for the house in the snowy season, or good, strongly-made carpet shoes; but these last, with a little ingenuity, you can make for yourself.

Flannel I also recommend, as an advisable purchase: you must give from 1s. 9d. to 2s. 6d. for either white or red, and a still higher price for fine fabrics; which I know is much higher than they can be bought for at home. Good scarlet or blue flannel shirts are worn by all the emigrants that work on land or at trades in Canada; and even through the hottest summer weather the men still prefer them to cotton or linen.

A superior quality, twilled and of some delicate check, as pale blue, pink or green, are much the fashion among the gentlemen; this [Pg 22] material however is more costly, and can hardly be bought under 3s. 6d. or 4s. a yard. A sort of overshirt made full and belted in at the waist, is frequently worn, made of home-spun flannel, dyed brown or blue, and looks neat and comfortable; others of coarse brown linen, or canvas, called logging-shirts, are adopted by the choppers in their rough work of clearing up the fallows: these are not very unlike the short loose slop frocks of the peasants of the Eastern Counties of England, reaching no lower than the hips.

Merino or cottage stuffs are also good to bring out, also Scotch plaids and tweeds, strong checks for aprons, and fine white cotton stockings: those who wear silk, had better bring a supply for holiday wear: satin shoes are very high, but are only needed by the wealthy, or those ladies who expect to live in some of the larger towns or cities; but the farmer's wife in Canada has little need of such luxuries—they are out of place and keeping.

[1] Since the above statement was written the wages both of men and women have borne a higher rate; and some articles of clothing have been raised in price. See the tables of rates of wages and goods for 1854.

It is one of the blessings of this new country, that a young person's respectability does by no means depend upon these points of style in dress; and many a pleasant little evening dance I have seen, where the young ladies wore merino frocks, cut high or low, and prunella shoes, and no disparaging remarks were made by any of the party. How much more sensible I thought these young people, than if they had made themselves slaves to the tyrant fashion. Nevertheless, in some of the large towns the young people do dress extravagantly, and even exceed those of Britain in their devotion to fine and costly apparel. The folly of this is apparent to every sensible person. When I hear women talk of nothing but dress, I cannot help thinking that it is because they have nothing more interesting to talk about; that their minds are uninformed, and bare, while their bodies are clothed with purple and fine linen. To dress neatly and with taste and even elegance is an accomplishment which I should desire to see practised by all females; but to make dress the one engrossing business and thought of life, is vain and foolish. One thing is certain, that a lady will be a lady, even in the plainest dress; a vulgar minded woman will never be a lady, in the most costly garments. Good sense is as much marked by the [Pg 23] style of a person's dress, as by their conversation. The servant-girl who expends half her wages on a costly shawl, or mantilla, and bonnet to wear over a fine shabby gown, or with coarse shoes and stockings, does not show as much sense as she who purchases at less cost a complete dress, each article suited to the other. They both attract attention, it is true; but in a different degree. The man of sense will notice the one for her wisdom; the other for her folly.—To plead fashion, is like following a multitude to do evil.

Quitting the subject of dress, which perhaps I have dwelt too long upon, I will go to a subject of more importance: the field which Canada opens for the employment of the younger female emigrants of the working class. At this very minute I was assured by one of the best and most intelligent of our farmers, that the Township of Hamilton alone could give immediate employment to five hundred females; and most other townships in the same degree. What an inducement to young girls to emigrate is this! good wages, in a healthy and improving country; and what is better, in one where idleness and immorality are not the characteristics of the inhabitants: where steady industry is sure to be rewarded by marriage with young men who are able to place their wives in a very different station from that of servitude. How many young women who were formerly servants in my house, are now farmers' wives, going to church or the market towns with their own sleighs or light waggons, and in point of dress, better clothed than myself.

Though Australia may offer the temptation of greater wages to female servants; yet the discomforts they are exposed to, must be a great drawback; and the immoral, disjointed state of domestic life, for decent, well-conducted young women, I should think, would more than counterbalance the nominal advantages from greater wages.—The industrious, sober-minded labourer, with a numerous family of daughters, one would imagine would rather bring them to Canada, where they can get immediate employment in respectable families; where they will get good wages and have every chance of bettering their condition and rising in the world, by becoming the wives of thriving farmers' sons or industrious artizans; than form connexions [Pg 24] with such characters as swarm the streets of Melbourne and Geelong, though these may be able to fill their hands with gold, and clothe them with satin and velvet.

In the one country there is a steady progress to prosperity and lasting comfort, where they may see their children become landowners after them, while in the other, there is little real stability, and small prospect of a life of domestic happiness to look forward to. I might say, as the great lawgiver said to the Israelites, "Good and evil are before yon, choose ye between them."

Those whose destination is intended to be in the Canadian towns will find little difference in regard to their personal comforts to what they were accustomed to enjoy at home. If they have capital they can employ it to advantage; if they are mechanics, or artizans they will have little difficulty in obtaining employment as journeymen.—The stores in Canada are well furnished with every species of goods; groceries, hardware and food of all kinds can also be obtained. With health and industry, they will have little real cause of complaint. It is those who go into the woods and into distant settlements in the uncleared wilderness that need have any fear of encountering hardships and privations; and such persons should carefully consider their own qualifications and those of their wives and children before they decide upon embarking in the laborious occupation of backwoodsmen in a new country like Canada. Strong, patient, enduring, hopeful men and women, able to bear hardships and any amount of bodily toil, (and there are many such,) these may be pioneers to open out the forestlands; while the old-country farmer will find it much better to purchase cleared farms or farms that are partially cleared, in improving townships, where there are villages and markets and good roads; by so doing they will escape much of the disappointment and loss, as well as the bodily hardships that are too often the lot of those who go back into the unreclaimed forestlands.

Whatever be the determination of the intended emigrant, let him not exclude from his entire confidence the wife of his bosom, the natural sharer of his fortunes, be the path which leads to them rough or smooth. She ought not to be dragged as an unwilling sacrifice at [Pg 25] the shrine of duty from home, kindred and friends, without her full consent: the difficulties as well as the apparent advantages ought to be laid candidly before her, and her advice and opinion asked; or how can she be expected to enter heart and soul into her husband's hopes and plans; nor should such of the children as are capable of forming opinions on the subject be shut out from the family council; for let parents bear this fact in mind, that much of their own future prosperity will depend upon the exertion of their children in the land to which they are going; and also let them consider that those children's lot in life is involved in the important decision they are about to make. Let perfect confidence be established in the family: it will avoid much future domestic misery and unavailing repining.—Family union is like the key-stone of an arch: it keeps all the rest of the building from falling asunder. A man's friends should be those of his own household.

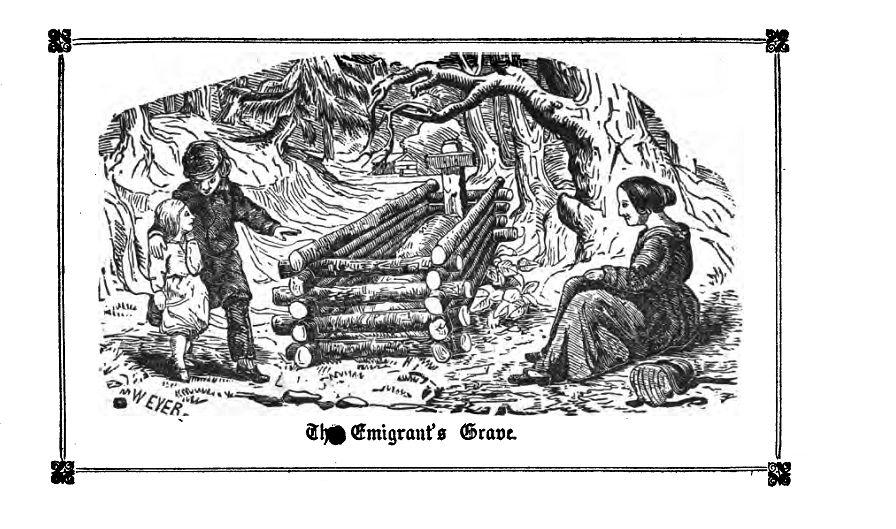

Woman, whose nature is to love home and to cling to all home ties and associations, cannot be torn from that spot that is the little centre of joy and peace and comfort to her, without many painful regrets. No matter however poor she may be, how low her lot in life may be cast, home to her is dear, the thought of it and the love of it clings closely to her wherever she goes. The remembrance of it never leaves her; it is graven on her heart. Her thoughts wander back to it across the broad waters of the ocean that are bearing her far from it. In the new land it is still present to her mental eye, and years after she has formed another home for herself she can still recall the bowery lane, the daisied meadow, the moss-grown well, the simple hawthorn hedge that bound the garden-plot, the woodbine porch, the thatched roof and narrow casement window of her early home. She hears the singing of the birds, the murmuring of the bees, the tinkling of the rill, and busy hum of cheerful labour from the village or the farm, when those beside her can hear only the deep cadence of the wind among the lofty forest-trees, the jangling of the cattle-bells, or strokes of the chopper's axe in the woods. As the seasons return she thinks of the flowers that she loved in childhood; the pale primrose, the cowslip and the bluebell, with the humble daisy and heath-flowers; and what would she not give for one, just one of those old familiar flowers! No wonder that the heart of the emigrant's wife is sometimes sad, and needs to be [Pg 26] dealt gently with by her less sensitive partner; who if she were less devoted to home, would hardly love her more, for in this attachment to home lies much of her charm as a wife and mother in his eyes.—But kindness and sympathy, which she has need of, in time reconciles her to her change of life; new ties, new interests, new comforts arise; and she ceases to repine, if she does not cease to love, that which she has lost: in after life the recollection comes like some pleasant dream or a fair picture to her mind, but she has ceased to grieve or to regret; and perhaps like a wise woman she says—"All things are for the best. It is good for us to be here."

What effect should this love of her old home produce in the emigrant-wife? Surely an earnest endeavour to render her new dwelling equally charming; to adorn it within and without as much as circumstances will permit, not expending her husband's means in the purchase of costly furniture which would be out of keeping in a log-house, but adopting such things as are suitable, neat and simple; studying comfort and convenience before show and finery. Many inconveniences must be expected at the outset; but the industrious female will endeavor to supply these wants by the exercise of a little ingenuity and taste. It is a great mistake to neglect those little household adornments which will give a look of cheerfulness to the very humblest home.

Nothing contributes so much to comfort and to the outward appearance of a Canadian house as the erection of the verandah or stoup, as the Dutch settlers call it, round the building. It affords a grateful shade from the summer heat, a shelter from the cold, and is a source of cleanliness to the interior. It gives a pretty, rural look to the poorest log-house, and as it can be put up with little expense, it should never be omitted. A few unbarked cedar posts, with a slab or shingled roof, costs very little. The floor should be of plank; but even with a hard dry earthen floor, swept every day with an Indian broom, it will still prove a great comfort. Those who build frame or stone or brick houses seldom neglect the addition of a verandah; to the common log-house it is equally desirable; nor need any one want for climbers with which to adorn the pillars.

Among the wild plants of Canada there are many graceful climbers, which are to be found in almost every locality. Nature, as if to invite you to ornament your cottage-homes, has kindly provided so many varieties of shade-plants, that you may choose at will.

First, then, I will point out to your attention the wild grape, which is to be found luxuriating in every swamp, near the margin of lakes and rivers, wreathing the trees and tall bushes with its abundant foliage and purple clusters. The Fox-grape and the Frost-grape[2] are among the common wild varieties, and will produce a great quantity of fruit, which, though very acid, is far from being unpalatable when cooked with a sufficiency of sugar.

From the wild grape a fine jelly can be made by pressing the juice from the husks and seeds and boiling it with the proportion of sugar usual in making currant-jelly, i e., one pound of sugar to one pint of juice. An excellent home-made wine can also be manufactured from these grapes. They are not ripe till the middle of October, and should not be gathered till the frost has softened them; from this circumstance, no doubt, the name of Frost-grape has been given to one species. The wild vine planted at the foot of some dead and unsightly tree, will cover it with its luxuriant growth, and convert that which would otherwise have been an unseemly object into one of great ornament. I knew a gentleman who caused a small dead tree to be cut down and planted near a big oak stump in his garden, round which a young grape was twining: the vine soon ascended the dead tree, covering every branch and twig, and forming a bower above the stump, and affording an abundant crop of fruit.

The commonest climber for a log-house is the hop, which is, as you will find, an indispensable plant in a Canadian garden, it being the principal ingredient in making the yeast with which the household bread is raised. Planted near the pillars of your verandah, it forms a graceful drapery of leaves and flowers, which are pleasing to look upon, and valuable either for use or sale.

[Pg 28] The Canadian Ivy, or Virginian Creeper, is another charming climber, which if planted near the walls of your house, will quickly cover the rough logs with its dark glossy leaves in summer, and in the fall delight the eye with its gorgeous crimson tints.

The Wild Clematis or Traveller's Joy may be found growing in the beaver meadows and other open thickets. This also is most ornamental as a shade-plant for a verandah. Then there is the climbing Fumatory, better known by the name by which its seeds are sold by the gardener, "Cypress vine." This elegant creeper is a native of Canada, and may be seen in old neglected clearings near the water, running up the stems of trees and flinging its graceful tendrils and leaves of tender green over the old grey mossy branches of cedar or pine, adorning the hoary boughs with garlands of the loveliest pink flowers. I have seen this climbing Fumatory in great quantities in the woods, but found it no easy matter to obtain the ripe seeds, unless purchased from a seedsman: it is much cultivated in towns as a shade plant near the verandahs.

Besides those already described I may here mention the scarlet-runner, a flower the humming-birds love to visit. The wild cucumber, a very graceful trailing plant. The Major Colvolvulus or Morning Glory. The wild honeysuckle, sweet pea and prairie-rose. These last-named are not natives, with the exception of the wild or bush honeysuckle, which is to be found in the forest. The flowers are pale red, but scentless; nevertheless it is very well worth cultivating.

I am the more particular in pointing out to you how you may improve the outside of your dwellings, because the log-house is rough and unsightly; and I know well that your comfort and cheerfulness of mind will be increased by the care you are led to bestow upon your new home in endeavouring to ornament it and render it more agreeable to the eye. The cultivation of a few flowers, of vegetables and fruit, will be a source of continual pleasure and interest to yourself and children, and you will soon learn to love your home, and cease to regret that dear one you have left.

I write from my own experience. I too have felt all the painful regrets incidental to a long separation from my native land and my beloved early home. I have experienced all that you who read this book can ever feel, and perhaps far more than you will ever have cause for feeling.

[2] There are many other varieties of wild grapes, some of which have, by careful garden cultivation, been greatly improved. Cuttings may be made early in April, or the young vines planted in September or October.

The emigrants of the present day can hardly now meet with the trials and hardships that were the lot of those who came to the Province twenty years ago, and these last infinitely less than those who preceded them at a still earlier period.

When I listen, as I often do, to the experiences of the old settlers of forty or fifty years standing, at a time when the backwoodsman shared the almost unbroken wilderness with the unchristianized Indian, the wolf and the bear; when his seed-corn had to be carried a distance of thirty miles upon his shoulders, and his family were dependent upon the game and fish that he brought home till the time of the harvest; when there were no mills to grind his flour save the little handmill, which kept the children busy to obtain enough coarse flour to make bread from day to day; when no sabbath-bell was ever heard to mark the holy day, and all was lonely, wild and savage around him. Then my own first trials seemed to sink into utter insignificance, and I was almost ashamed to think how severely they had been felt.

Many a tale of trial and of enterprize I have listened to with breathless interest, related by these patriarchs of the colony, while seated beside the blazing log-fire, surrounded by the comforts which they had won for their children by every species of toil and privation. Yet they too had overcome the hardships incidental to a first settlement, and were at rest, and could look back on their former struggles with that sort of pride which is felt by the war-worn soldier in fighting over again his battles by his own peaceful hearth.

These old settlers and their children have seen the whole face of the country changed. They have seen the forest disappear before the axe of the industrious emigrant; they have seen towns and villages spring up where the bear and the wolf had their lair. They have seen the white-sailed vessel and the steamer plough those lakes and rivers where the solitary Indian silently glided over their lonely waters in his frail canoe. They have seen highways opened out through impenetrable swamps where human foot however adventurous had never trod. The busy mill-wheels have dashed where only the foaming rocks broke the onward flow of the forest stream. They have seen God's holy temples rise, pointing upwards with their glittering [Pg 30] spires above the lowlier habitations of men, and have heard the sabbath-bell calling the Christian worshippers to prayer. They have seen the savage Indian bending there in mute reverence, or lifting his voice in hymns of praise to that blessed Redeemer who had called him out of darkness into his marvellous light. And stranger things he may now behold in that mysterious wire, that now conveys a whispered message from one end of the Province to the other with lightning swiftness; and see the iron railway already traversing the Province, and bringing the far-off produce of the woods to the store of the merchant and to the city mart.

Such are the changes which the old settler has witnessed; and I have noted them for your encouragement and satisfaction, and that you may form some little notion of what is going on in this comparatively newly-settled country; and that you may form some idea of what it is likely to become in the course of a few more years, when its commerce and agriculture and its population shall have increased, and its internal resources shall have been more perfectly developed.

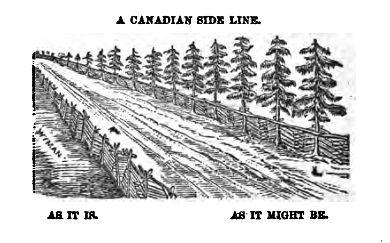

In the long-settled portions of the Province a traveller may almost imagine that he is in England; there are no stumps to disfigure the fields, and but very few of the old log-houses remaining: these have for the most part given place to neat painted frame, brick or stone cottages, surrounded with orchards, cornfields and pastures. Some peculiarities he will notice, which will strike him as unlike what he has been used to see in the old country; and there are old familiar objects which will be missed in the landscape, such as the venerable grey tower of the old church, the ancient ruins, the old castles and fine old manor-houses, with many other things which exist in the old country. Here all is new; time has not yet laid its mellowing touch upon the land. We are but in our infancy; but it is a vigorous and healthy one, full of promise for future greatness and strength.

In furnishing a Canadian log-house the main study should be to unite simplicity with cheapness and comfort. It would be strangely out of character to introduce gay, showy, or rich and costly articles of furniture into so rough and homely a dwelling. A log-house is [Pg 31] better to be simply furnished. Those who begin with moderation are more likely to be able to increase their comforts in the course of a few years.

Let us see now what can be done towards making your log parlour comfortable at a small cost. A dozen of painted Canadian chairs, such as are in common use here, will cost you £2 10s. You can get plainer ones for 2s. 9d. or 3s. a chair: of course you may get very excellent articles if you give a higher price; but we are not going to buy drawing-room furniture. You can buy rocking chairs, small, at 7s. 6d.; large, with elbows, 15s.: you can cushion them yourself. A good drugget, which I would advise you to bring with you, or Scotch carpet, will cover your rough floor; when you lay it down, spread straw or hay over the boards; this will save your carpet from cutting. A stained pine table may be had for 12s. or 15s. Walnut or cherry wood costs more; but the pine with a nice cover will answer at first. For a flowered mohair you must give five or six dollars. A piece of chintz of suitable pattern will cost you 16s. the piece of twenty-eight yards. This will curtain your windows: and a common pine sofa stuffed with wool, though many use fine hay for the back and sides, can be bought cheap, if covered by your own hands. If your husband or elder sons are at all skilled in the use of tools, they can make out of common pine boards the frame-work or couches, or sofas, which look when covered and stuffed, as well as what the cabinet-maker will charge several pounds for. A common box or two stuffed so as to form a cushion on the top, and finished with a flounce of chintz, will fill the recess of the windows. A set of book-shelves stained with Spanish brown, to hold your library.—A set of corner shelves, fitted into the angles of the room, one above the other, diminishing in size, form an useful receptacle for any little ornamental matters, or for flowers in the summer, and gives a pleasant finish and an air of taste to the room. A few prints, or pictures, in frames of oak or black walnut, should not be omitted, if you can bring such ornaments with you. These things are sources of pleasure to yourselves, and of interest to others. They are intellectual luxuries, that even the very poorest man regards with delight, and possesses if he can, to adorn his cottage walls, however lowly that cottage may be.

I am going to add another comfort to your little parlour—a clock: very neat dials in cherry or oak frames, may be bought from 7s. 6d. to $5. The cheapest will keep good time, but do not strike. Very handsome clocks may be bought for ten dollars, in elegant frames; but we must not be too extravagant in our notions.

I would recommend a good cooking-stove in your kitchen: it is more convenient, and is not so destructive to clothes as the great log fires. A stove large enough to cook food for a family of ten or twelve persons, will cost from twenty to thirty dollars. This will include every necessary cooking utensil. Cheap stoves are often like other cheap articles, the dearest in the end: a good, weighty casting should be preferred to a thinner and lighter one; though the latter will look just as good as the former: they are apt to crack, and the inner plates wear out soon.

There are now a great variety of patterns in cooking-stoves, many of which I know to be good. I will mention a few:—"The Lion," "Farmers' Friend," "Burr," "Canadian Hot-Air," "Clinton Hot-Air;" these two last require dry wood; and the common "Premium" stove, which is a good useful stove, but seldom a good casting, and sold at a low price. If you buy a small-sized stove, you will not be able to bake a good joint of meat or good-sized loaves of bread in it.

If you have a chimney, and prefer relying on cooking with the bake-kettle, I would also recommend a roaster, or bachelor's oven: this will cost only a few shillings, and prove a great convenience, as you can bake rolls, cakes, pies and meat in it. An outside oven, built of stones, bricks, or clay, is put up at small cost, and is a great comfort.[3] The heating it once or twice a week, will save you much work, and you will enjoy bread much better and sweeter than any baked in a stove, oven or bake-kettle.

Many persons who have large houses of stone or brick, now adopt the plan of heating them with hot air, which is conveyed by means of pipes into the rooms. An ornamented, circular grating admits [Pg 33] the heated air, by opening or shutting the grates. The furnace is in the cellar, and is made large enough to allow of a considerable quantity of wood being put in at once.

A house thus heated is kept at summer heat in the coldest weather; and can be made cooler by shutting the grates in any room.

The temperature of houses heated thus is very pleasant, and certainly does not seem so unhealthy as those warmed by metal stoves, besides there being far less risk from fire.

Those who wish to enjoy the cheerful appearance of a fire in their sitting room, can have one; as little wood is required in such case.

The poorer settlers, to whom the outlay of a dollar is often an object, make very good washing tubs out of old barrels, by sawing one in half, leaving two of the staves a few inches higher than the rest, for handles. Painted washing-tubs made of pine, iron hooped, cost a dollar; painted water-pails only 1s. 6d. a piece; but they are not very durable. Owing to the dryness of the air, great care is requisite to keep your tubs, barrels and pails in proper order. Many a good vessel of this kind is lost for want of a little attention.

The washing tubs should be kept in the cellar, or with water in them. Those who keep servants must not forget to warn them of this fact.

In fitting up your house, do not sacrifice all comfort in the kitchen, for the sake of a best room for receiving company.

If you wish to enjoy a cheerful room, by all means have a fireplace in it. A blazing log-fire is an object that inspires cheerfulness. A stove in the hall or passage is a great comfort in winter; and the pipe conducted rightly will warm the upper rooms; but do not let the stove supersede the cheering fire in the sitting-room. Or if your house has been built only to be heated by stoves, choose one that, with a grate in front, can be opened to show the fire. A handsome parlour-stove can now be got for twelve dollars. Tanned and dyed sheep-skins make excellent door mats, and warm hearth-rugs. With small outlay of money your room will thus be comfortably furnished.

A delightful easy-chair can be made out of a very rough material—nothing better than a common flour barrel. I will, as well as I [Pg 34] can, direct you how these barrel-chairs are made. The first four or five staves of a good, sound, clean flour barrel are to be sawn off, level, within two feet of the ground, or higher, if you think that will be too low for the seat: this is for the front: leave the two staves on either side a few inches higher for the elbows; the staves that remain are left to form the hollow back: augur holes are next made all round, on a level with the seat, in all the staves; through these holes ropes are passed and interlaced, so as to form a secure seat: a bit of thin board may then be nailed, flat, on the rough edge of the elbow staves, and a coarse covering, of linen or sacking, tacked on over the back and arms: this is stuffed with cotton-wool, soft hay, or sheep's wool, and then a chintz cover over the whole, and well-filled cushion for the seat, completes the chair. Two or three of such seats in a sitting-room, give it an air of great comfort at a small cost.

Those settlers who come out with sufficient means, and go at once on cleared farms, which is by far the best plan, will be able to purchase very handsome furniture of black walnut or cherry wood at moderate cost. Furniture, new and handsome, and even costly, is to be met with in any of the large towns; and it would be impertinent in me to offer advice as to the style to be observed by such persons: it is to the small farmer, and poorer class, that my hints are addressed.

The shanty, or small log-house of the poorer emigrant, is often entirely furnished by his own hands. A rude bedstead, formed of cedar poles, a coarse linen bag filled with hay or dried moss, and bolster of the same, is the bed he lies on; his seats are benches, nailed together; a table of deal boards, a few stools, a few shelves for the crockery and tinware; these are often all that the poor emigrant can call his own in the way of furniture. Little enough and rude enough. Yet let not the heart of the wife despond. It is only the first trial; better things are in store for her.

Many an officer's wife, and the wives of Scotch and English gentlemen, in the early state of the colony have been no better off.—Many a wealthy landowner in Canada was born in circumstances as unfavourable. Men who now occupy the highest situations in the country, have been brought up in a rude log-shanty, little better than an Indian wigwam. Let these things serve to cheer the heart and [Pg 35] smooth the rough ways of the settler's first outset in Canadian life.—And let me add that now there is more facility for the incoming emigrant's settling with comfort, than there was twenty or thirty years ago; unless he goes very far back into the uncivilized portions of the country, he cannot now meet with the trials and privations that were the lot of the first settlers in the Province. And there is no necessity for him to place himself and family beyond the outskirts of civilization. Those who have the command of a little capital can generally buy land with some clearing and buildings; and the working man can obtain good employment for his wife and elder girls or boys, so as to enable them by their united savings, to get a lot of land for themselves, to settle upon. This is more prudent than plunging at once into the bush, without possessing the experience which is necessary for their future welfare, almost for their very existence, in their new mode of life. When they have earned a little money, and some knowledge of the ways of the country, they may then start fair, and by industry and sobriety, in a few years become independent.

To pay for his land by instalments, is the only way a poor man can manage to acquire property: to obtain his deed, is the height of his ambition: to compass this desirable end all the energies of the household are directed. For this the husband, the wife, the sons and the daughters all toil: each contributes his or her mite: for this they endure all sorts of privations, without murmuring. In a few years the battle is won. Poverty is no longer to be feared.

The land is their own: with what pride they now speak of it; with what honest delight they contemplate every blade of wheat, every ear of corn, and the cattle that feed upon their pastures. No rent is now to be paid for it. God has blessed the labours of their hands. Let them not forget that to him is the glory and praise due.

When they have acquired land and cattle, let them not in the pride of their hearts say—"My hand and the power of my arm has gotten me all these;" for it is God that giveth the increase in all these things.

[3] Two men, or a man and a boy will build a common-sized clay oven in a day or less, if they understand the work and prepare the materials beforehand.

With habits of industry long practiced, cheered by a reasonable hope, and with experience gained, no one need despair of obtaining [Pg 36] all the essential comforts of life; but strict sobriety is indispensably necessary to the attainment of his hopes. Let not the drunkard flatter himself that success will attend his exertions. A curse is in the cup; it lingers in the dregs to embitter his own life and that of his hapless partner and children. As of the sluggard, so also may it be said of the intemperate—"The drunkard shall starve in harvest." It is in vain for the women of the household to work hard and to bear their part of the hardships incidental to a settler's life, if the husband gives himself up as a slave to this miserable vice.

I dwell more earnestly upon this painful subject, because unfortunately the poison sold to the public under the name of whiskey, is so cheap, that for a few pence a man may degrade himself below the beasts that perish, and barter away his soul for that which profiteth not; bring shame and disgrace upon his name, and bitterness of heart into the bosom of his family. I have known sad instances of this abhorrent vice, even among the women; and they have justified themselves with saying—"We do it in self-defence, and because our husbands set us the example: it is in vain for us to strive and strive; for everything is going to ruin." Alas that such a plea should ever be made by a wife. Let the man remember that God has set him for the support of the wife: he is the head, and should set an example of virtue, and strength, rather than of vice and weakness. Let both avoid this deadly sin, if they would prosper in life, and steadfastly resist the temptation that besets them on every side. And not to the poor man alone would I speak; for this evil habit pervades all classes; and many a young man of fair expectations is ruined by this indulgence, and many a flourishing home is made desolate by him who founded it. The last state of this man is worse than the first.

It is a matter of surprize to many persons to see the great amount of energy of mind and personal exertion that women will make under the most adverse circumstances in this country. I have marked with astonishment and admiration acts of female heroism, for such it may be termed in women whose former habits of life had exempted them from any kind of laborious work, urged by some unforeseen exigency, [Pg 37] perform tasks from which many men would have shrunk. Sometimes aroused by the indolence and inactivity of their husbands or sons, they have resolutely set their own shoulders to the wheel, and borne the burden with unshrinking perseverence unaided; forming a bright example to all around them, and showing what can be done when the mind is capable of overcoming the weakness of the body.

A poor settler was killed by the fall of a tree, in his fallow. The wife was left with six children, the youngest a babe, the eldest a boy of fourteen. This family belonged to the labouring class. The widow did not sit down and fold her hands in utter despair, in this sad situation; but when the first natural grief had subsided, she roused herself to do what she could for the sake of her infants. Some help no doubt she got from kind neighbours; but she did not depend on them alone. She and her eldest son together, piled the brush on the new fallow; and with their united exertions and the help of the oxen, they managed to log and burn off the Spring fallow. I dare say they got some help, or called a logging Bee, to aid in this work.—They managed, this poor widow and her children, to get two or three acres of wheat in, and potatoes, and a patch of corn; and to raise a few vegetables. They made a brush fence and secured the fields from cattle breaking in, and then harvested the crops in due time, the lad working out sometimes for a week or so, to help earn a trifle to assist them.

That fall they underbrushed a few acres more land, the mother helping to chop the small trees herself, and young ones piling the brush. They had some ague, and lost one cow, during that year; but still they fainted not, and put trust in Him who is the helper of the widow and fatherless. Many little sums of money were earned by the boys shaping axe-handles, which they sold at the stores, and beech brooms: these are much used about barns and in rough work. They are like the Indian brooms, peeled from a stick of ironwood, blue-beech, or oak. Whip-handles of hickory, too, they made. They sold that winter maple sugar and molasses; and the widow knitted socks for some of the neighbours, and made slippers of listing. The boys also made some money by carrying in loads of oak and hemlock bark, to the tanners, from whom they got orders on the stores for groceries, clothes and such things. By degrees their stock increased, [Pg 38] and they managed by dint of care and incessant labour to pay up small instalments on their land. How this was all done by a weak woman and her children, seems almost a miracle, but they brought the strong will to help the weak arm.

I heard this story from good authority, from the physician who attended upon one of the children in sickness, and who had been called in at the inquest that was held on the body of her husband.

Dr. H. often named this woman as an example of female energy under the most trying circumstances; and I give it to show what even a poor, desolate widow may do, even in a situation of such dire distress.

And now I would say a few words about borrowing—a subject on which so much has been said by different writers who have touched upon the domestic peculiarities of the Canadians and Yankees.

In a new settlement where people live scattered, and far from stores and villages, the most careful of housewives will sometimes run out of necessaries, and may be glad of the accommodation of a cupful of tea, or a little sugar; of barm to raise fresh rising, or flour to bake with. Perhaps the mill is far off, and the good man has been too much occupied to take in a grist. Or medicine may be needed in a case of sudden illness.

Well, all these are legitimate reasons for borrowing, and all kindly, well-disposed neighbours will lend with hearty good-will: it is one of the exigencies of a remote settlement, and happens over and over again.

But as there are many who are not over scrupulous in these matters, it is best to keep a true account in black and white, and let the borrowed things be weighed or measured, and returned by the same weight and measure. This method will save much heart-burning and some unpleasant wrangling with neighbours; and if the same measure is meted to you withal, there will be no cause of complaint on either side. On your part be honest and punctual in returning, and then you can with a better face demand similar treatment.

Do not refuse your neighbours in their hour of need, for you also may be [Pg 39] glad of a similar favour. In the Backwoods especially, people cannot be independent of the help and sympathy of their fellow creatures. Nevertheless do not accustom yourself to depend too much upon any one.

Because you find by experience that you can borrow a pot or a pan, a bake-kettle or a washing-tub, at a neighbour's house, that is no good reason for not buying one for yourself, and wearing out Mrs. So-and-so's in your own service. Once in a while, or till you have supplied the want, is all very well; but do not wear out the face of friendship, and be taxed with meanness.

Servants have a passion for borrowing, and will often carry on a system of the kind for months, unsanctioned by their mistresses; and sometimes coolness will arise between friends through this cause. In towns there is little excuse for borrowing: the same absolute necessity for it does not exist.

If a neighbour, or one who is hardly to be so called, comes to borrow articles of wearing apparel, or things that they have no justifiable cause for asking the loan of, refuse at once and unhesitatingly.

I once lived near a family who made a dead set at me in the borrowing way. One day a little damsel of thirteen years of age, came up quite out of breath to ask the loan of a best night-cap, as she was going out on a visit; also three nice worked-lace or muslin collars—one for herself, one for her sister, and the third was for a cousin, a new-arrival; a pair of walking-boots to go to the fair in at ——, and a straw hat for her brother Sam, who had worn out his; and to crown all, a small-tooth comb, "to redd up their hair with, to make them nice."

I refused all with very little remorse; but the little damsel looked so rueful and begged so hard about the collars, that I gave her two, leaving the cousin to shift as she best could; but I told her not to return them, as I never lent clothes, and warned her to come no more on such an errand. She got the shoes elsewhere, and, as I heard they were worn out in the service before they were returned. Now against such a shameless abuse of the borrowing system, every one is justified in making a stand: it is an imposition, and by no means to be tolerated.

[Pg 40] Another woman came to borrow a best baby-robe, lace-cap and fine flannel petticoat, as she said she had nothing grand enough to take the baby to church to be christened in. Perhaps she thought it would make the sacrifice more complete if she gave ocular demonstration of the pomps and vanities being his to renounce and forsake.

I declined to lend the things, at which she grew angry, and departed in a great pet, but got a present of a handsome suit from a lady who thought me very hard-hearted. Had the woman been poor, which she was not, and had begged for a decent dress for the little Christian, she should have had it; but I did not respect the motive for borrowing finer clothes than she had herself, for the occasion.

I give these instances that the new comer may distinguish between the use and the abuse of the system; that they may neither suffer their good nature and inexperience to be imposed upon, nor fall into the same evil way themselves, or become churlish and unfriendly as the manner of some is.

One of the worst points in the borrowing system is, the loss of time and inconvenience that arises from the want of punctuality in returning the thing lent: unless this is insisted upon and rigorously enforced, it will always remain, in Canada as elsewhere, a practical demonstration of the old adage—"Those who go borrowing, go sorrowing;" they generally lose a friend.

There is one occasion on which the loan of household utensils is always expected: this is at "Bees", where the assemblage always exceeds the ways and means of the party; and as in country places these acts of reciprocity cannot be dispensed with, it is best cheerfully to accord your help to a neighbour, taking care to count knives, forks, spoons, and crockery, or whatever it may be that is lent carefully, and make a note of the same, to avoid confusion. Such was always my practice, and I lived happily with neighbours, relations and friends, and never had any misunderstanding with any of them.

I might write an amusing chapter on the subject of borrowing; but I leave it to those who have abler pens than mine, and more lively talents, for amusing their readers.

In the choice of a vessel in which to embark for Canada, those persons who can afford to do so, will find better accommodations and more satisfaction in the steamers that ply between Liverpool and Quebec, than in any of the emigrant ships. The latter may charge a smaller sum per head, but the difference in point of health, comfort and respectability will more than make up for the difference of the charge. The usual terms are five or six pounds for grown persons; but doubtless a reduction on this rate would be made, if a family were coming out. To reach the land of their adoption in health and comfort, is in itself a great step towards success. The commanders of this line of ships are all men of the highest respectability, and the poor emigrant need fear no unfair dealing, if they place themselves and family under their care. At any rate the greatest caution should be practiced in ascertaining the character borne by the captains and owners of the vessels in which the emigrant is about to embark; even the ship itself should have a character for safety, and good speed. Those persons who provide their own sea-stores, had better consult some careful and experienced friend on the subject. There are many who are better qualified than myself, to afford them this valuable information.