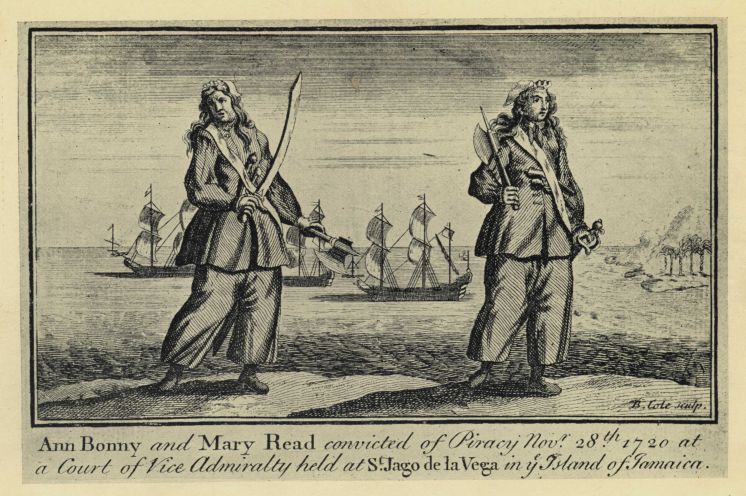

Ann Bonny and Mary Read convicted of Piracy, Nov. 28th, 1720, at a Court

of Vice Admiralty held at St. Jago de la Vega in ye Island of Jamaica.

by

FRANK SHAY

HURST & BLACKETT, LTD.

PATERNOSTER HOUSE, E.C.4

Made and Printed in Great Britain for

Hurst & Blackett, Ltd., Paternoster House, London, E.C.4, at

The Mayflower Press, Plymouth. William Brendon & Son, Ltd.

By the same Author

IRON MEN AND WOODEN SHIPS

MY PIOUS FRIENDS AND DRUNKEN COMPANIONS

HERE'S AUDACITY

INCREDIBLE PIZARRO

etc. etc.

TO

FRANCES EDITH FOLEY

WITH LOVE

The heroine of this book of adventure on the Western Seas is Mary Read, who lived and died in the manner pictured here. Serving first as an officer under many famous buccaneers, she later commanded her own vessel, and led her men in boarding fat Spanish galleons and in the rape of New Orleans. Death came to her in a manner befitting her career. So much as is known of her life is embodied in this tale of her scouring the seas.

I wish to take this opportunity to acknowledge the valuable aid and research of E. Irvine Haines, historian of the period.

F.S.

CONTENTS

BOOK ONE

BOOK TWO

BOOK THREE

BOOK FOUR

BOOK FIVE

THE PEOPLE

Mary Read

Boatswain Jones

Edwin Brangwin, the Governor's Son

Anne Bonney

Mrs. Anne Fulworth

Calico Jack Rackham

Governor Woodes Rogers

INCIDENTAL PEOPLE

Moll Read

John Martell

Captain Skinner

Howell Davis

Charles Bellamy, the socialistic pirate

Stede Bonnet, the hen-pecked pirate

William Fly, the prize-fighter

Charles Vane

Edward Low, the meanest pirate

William Lewis

Edward Teach, alias Blackbeard

Edward England

Kit Winter, the admiral

Captain Sawney, the "governor"

George Lowther

Bartholomew Roberts

Frank Spriggs

Dick Turnley

Will Cunningham, first to refuse the King's Pardon

Jim Fife, the first to accept the King's Pardon

Captain Yeates

and Others

I

The low-ceilinged, long room of The Saylor's True Friende was warm and bright against the black coldness of the November night. Outside the winds blew across the quays of Bristol Town, rattling windows and doors; inside the swarming patrons, shouting and laughing, were fortifying themselves against the short cold trip that would divide them, even to their loyalties, between the two ships standing out in the roadstead. Before dawn they would catch the flood that would carry them to their separate ways.

In one corner of the room sat the august Captain Skinner, master of the Cadagon, snow, out of this very Bristol, with a miscellaneous cargo for trading along the Guinea Coasts and in the Bahamas. If he found those things which he sought he would continue to Charleston, to New York and Boston before turning his ship homeward. About him were grouped his men, two with coddling wenches on their knees, the rest content to coddle their jorums of hot rum. In another corner was Master John Martell of The King's Fancy, brigantine, out of Cardiff. There were more wenches among his company and the men were drinking brandies, Genevas and tots of straight rum, for money was freer among Martell's raffish company.

The staff of the tavern handled the huge throng expertly. Mine host, who answered to the name of Marcus Cribb, presided behind the long oaken counter, passing mugs, tankards and glasses to Moll Read and to her son, Buttons, a stripling of sixteen, whose already roughened hands show he is no stranger to hard work. The lad is straight and fair, his hair caught behind his ears in a tiny pigtail, his cotton shirt buttoned tight to the neck. His breeches and woollen stockings though well worn show that he takes some pride in his personal appearance. At every opportunity he listens to the talk of strange places and stranger people.

The ships' masters were completing their companies and, with the exception of the staff of the tavern, all but one man there had been signed. Skinner's papers lay on the table in front of him, but Martell's were brought out only when a man was ready to sign or put his mark to the articles. To all outward appearances both voyages were on honourable and legal intent, but Martell's price was higher and the first requisite for membership was the possession of a cutlass, one or more pistols and a stout right arm. In days now gone Martell had been a pirate; that was known, but only those who signed his papers could tell that once again he was on the account. Good Captain Skinner's name was above reproach, as every Bristol man well knew.

Pirates ashore? Pirates ashore and rubbing elbows with the very men who with the turn of the tide or shift in the winds might become their next prey? Bad times were upon Old England, and it was only fair that Bristol folk should be alive to their opportunities. King George the First, disliking his chilly realm, and likewise the people whose language he did not speak and whose politics he did not understand, had left for his beloved Hanover, for his full-breasted mistresses and his own people. He had placed the Prince of Wales at the head of the country, temporarily of course, and that worthy, bitterly disliking his father's policies, was busily changing them to suit his own fancy. There was confusion in Britain; no one knew who was master but all were willing to play one against t'other, if there were a profit to it.

"Last chance," announced Master Skinner. "I have room for but two more men. You there, Jorgen, how now? You be a good hand an' you know my snow an' you have the purchase. Or do you sail wi' yon picaroon?"

The man addressed leaned back and waved a happy hand. He was fair drunk or he would have been on his feet, hat in hand, and clutching his forelock.

"Nay, Master Skinner. I vowed a wench to stop over a bit an' I be a man o' my word, as well you know. Nor do I go with yon buccaroon. I may yet change my mind and board the Cadogan before she takes the tide."

Moll Read, mistress of the tavern and of mine host, edged her boy towards Master Skinner.

"Oooee, marster," she cooed. "'Ere's the lad for 'ee. A strong bully, a-feared o' none. Wot'll you gi'e for 'im?"

"Give, Moll, wench? I'm no master that needs to give a bounty to make up his company. I leave that to 'Is Majesty, King George, be he First or Second, and to yon Martell, the picaroon. He might give a pretty penny to fill out his company."

"Martell's arsking fifty guineas," announced an unknown.

Hard times indeed in Old Bristol. Bristol Town's a sailor's town and Bristol women are sailors' women. Time was, before the German took the throne, that would be in Good Queen Anne's reign, that a master must needs put out good gold in advance to win a sailor's services. Now they required their companies to share the dangers of a little freebooting on the side. Skinner, for instance, taking ten guineas from each of twenty-five men and as much as his officers could afford, would place a like total with theirs and use it all in a special trading account. In such a voyage as he now planned the amount would be trebled or even quadrupled and each man would get his fair share. He made his crew partners, at the same time sealing their lips if in his trading he exceeded the bounds of lawful trade. Too, he secured their services without further wage, save the shilling a day they would get from the Admiralty. To make the offer more attractive each man was permitted to trade on his own provided he shared his gains with his master.

"Mister Skinner," called a loud voice from Martell's table. "Mister Skinner, by what token do ye call me pirate?"

The patrons looking in the direction of the speaker saw that it was John Martell himself.

"Ho! Who dares say ye be no pirate? A pirate confessed ye be an' yer head's where it is only because 'Is Majesty's sarvants are a stinking lot of cringing knaves without courage to tighten the rope. If you had your deserts we'd be dropping a cheer as we passed you in chains."

"I've a mind to——" began John Martell.

"Only honest seafarers have minds to do the right thing. Ye no dare to call the watch nor the aldermen either."

The disputants made no attempt to advance upon each other; only Moll Read was active.

"'Ere's a mon for 'ee, Martell, that'll surprise 'ee. Take 'im for ten pound."

"Nay, wench, I'm 'aving a word with Mister Skinner."

But the pirate's opponent had sat down and he was without words. He was not a Bristolman and he was in Bristol only on tolerance. One overt act and the hand of every man, even to the Bristolmen in his own company, would be raised against him. Wisely he took advantage of Moll Read's interruption and resumed his own seat.

"Five, then, an' he's yours for all time. I want 'im out o' the hoose before the sun rises, I'm that sick o' his blokey face."

"Nay, Moll, I pay for no hand. I'll take 'im on for 'alf a share at twenty guineas. It's a bargain an' I do it only for you."

Moll screamed: "But I'm sellin' the fool, d'ye understand?"

"No trade," said the pirate with finality. "I like the lad's looks an' I need such a boy for my cabin. Aye, Moll, m'own, on second thought I'll take 'im for nothin' an' let 'im earn what he can sarving the company."

"Oooee," cooed Moll, "an' will the good marster gi'e me two golden guineas to seal the bargain?"

"Aye, Moll, when The King's Fancy returns to this blighted port. Ha! ha! ha! Keep your devil's brat; he looks like hell's own spit and blood." He rose to his feet. "Be getting along, my bullies, we'll complete our company at Cardiff."

Moll Read screamed another curse upon the master, his vessel and its voyage.

"It'll be strange work that I'll put that lad to before another day's done. I should a done it the week past, more to my own profit." To the lad she hissed, "Make a ship, bastard, elst I'll expose 'ee."

The watch entered at this moment and, striking his staff to the floor to gain attention, cried:

"Twelve is the hour and God's peace be on Old Bristol. To your wessels or to your homes. 'Tis the King's law."

He took up his solemn position near the door and waited as the men filed out, first Martell's company and then Master Skinner's. The wenches hurried off into the night.

Moll Read and mine host left by a back door and only the lad Moll had called Buttons Read and the half-drunken sailor were left.

"Do you go to your lodging, mon?" demanded the watch of the sailor.

"Aye, I'm there. I'm stopping here the night, if it please you, the watch. Is it not so, lad?"

"'Tis so, master," said the youth. "Your bed's above the stairs." He then went about his task of putting out the lanterns that hung about the room.

The watch, convinced that all was in order, went out into the night and to his rounds.

When all the lights but the one above the bar had been extinguished and the lad was waiting the sailor's departure, that worthy demanded another drink. He rose to his feet, it could be seen he was no more drunk than when he entered, and came to the oaken bar.

"A stiff jorum, make it, lad. It's cold the night an' I've to make my way to the High Street."

"Your bed's aloft," the lad began.

The sailor winked broadly.

"Aye, a shilling wasted but there's many a 'alf-empty bed in Bristol that needs warmin' and fillin'."

The lad who a few minutes before had seemed to be but a riverside lout was now all attention.

"You're of Master Skinner's company, I trow. Yet you took lodging here and your vessel leaves before dawn."

"Aye, an' much may happen before dawn. There's five hours that can stand a bit o' improvin'. Why do you stick to this tavern? I heard Moll trying to join you up to either company. Moll has many times the ten guineas Master Skinner asks."

"I'm not ready yet," answered the lad. "My ship'll be a fast one, one that I may be proud to name mine own. One that will go to the Indies, mayhap to Tasman's land and Cathay and Cipango. A privateer or a letter of marque, should my King need me."

"The King's shillin' is poor pay an' a marster must look sharp about 'im to 'old 'is men. Skinner's an honest man, by any way you look on't. But he's not above turnin' an 'appy penny or two by loadin' slaves at some port 'e drifts into. 'Oo's to say 'e's wrong to turn misfortune to an 'andy profit? Take last voyage: we stowed forty blacks in the lazareet an' sailed as proud's you please into Charlestown Harbour, right under the nose o' the King's Governor, if you please, and sold 'em at fifty guineas the 'ead. That's not piracy, nor privateerin' either. Privateerin's but a step to piracy and it's another to Tyburn Hill or Wapping's Execution. Win your beard first, m'lad, afore you tempt the gibbet."

"I'll cheat the gallows——"

"The boast of every rogue, yet most o' them swing afore they've learned to live." The sailor flushed his throat from his tankard.

"Tell me sum'mat more o' Boston Town, marster," pleaded the boy, his arms on the bar.

"It's a bonnie town, a bit o' old Bristol. Indeed, to many it be Bristol beyond the seas and there's many a comely wench there awaiting a likely lad to tell her downright his business with her. 'Zounds, they've a game they call bundling, but your ears are too soft to hear o' it."

The lad blushed.

"Aye," laughed the sailor. "You must have a wench tell you how 'tis played or not learn it at all. There's yet time to join wi' Skinner. Say the word!"

"I'll not say it. My ship's not yet built."

"There'll be a handy profit this time. With a good trading and fair winds there should be ten times ten guineas for each and all."

"To my thinking 'tis no better than piracy," said the lad. "Why not go all the way and join Master Maxell's company?"

"A curse upon the man an' 'is vessel! A-robbin' 'onest British ships an' a-defyin' good King Jarge. I'm no blackbird, m'lad, but only a British s'iling man lookin' to turn an extry penny."

The sailor threw a well-filled purse upon the bar.

"Be having your score from that, lad, an' I'll be about my business." He applied himself to his tankard.

The boy's eyes glistened at the sight of the stout purse and his ears thrilled to the clink of gold coins. His manner changed at once and his eyes, laughing into those of the patron, did not follow his hands as they became engaged beneath the bar.

"Let me be 'freshing up your rum, marster, while you tell me more." The youth was about strange business and needed his eyes as well as his hands. The sailor took a final gulp from his tankard and set it down.

"You must be all o' sixteen, fellow, and weigh upwards o' ten stone, an' it's time for ye to be out o' this swyvin' and crimpin' 'ole. It has a foul name. Tell you what I'll do: I'll go settle wi' yon wench and return here and take you to the Cadogan. What say? I like your trim, lad."

"I'm not wi' the ten guineas, master," answered the youth as he returned the tankard to the drinker. His voice trembled a bit, not in fear of what he had put in the sailor's mug, but that he had bungled. The man was fair game and had Moll Read glimpsed the purse on the bar she would have been doing the same thing. He was sure he had not bungled, he had watched Moll often enough since he had returned from Flanders and Holland.

He had come back to Bristol Town and asked the whereabouts of Moll Read and he had known where to ask and where not to mention her name. So Buttons had hurried to The Saylor's True Friende expecting to be recognized at once. Hopefully he had gone to the tables served by Moll and ordered a tot of rum. And, instead of a greeting, he had been insulted. Because of his youth and apparent insolvency his score had been demanded before he was permitted to put hand to tankard.

He had tossed his purse upon the table and Moll had as quickly changed her manner.

"Ooee, a fine lad," she had cooed, "an' it's a better tot he deserves wi' so much gilt i' his pocket." She had forthwith returned to the bar and drawn him a special dram, "'The Landlord's Own', m'hearty!" and placed it before him with a smirk. The Landlord's Own had proved too much for the lad, and whilst he had lain drugged Moll had filched his purse, unknowing that her victim was her own flesh and blood.

Later on learning his identity, she had taken the incident as a huge joke, had told of her error with great gusto, yet had done nothing towards making amends for it.

If he had his purse now, with its contents, he might hope to buy a station on the Cadogan. But Moll was in no mood for restitution. She'd far rather crimp her own than pay one red farthing towards forwarding his desires.

Now, if the sailor would but drink quickly, he'd still have time for the Cadogan. To make conversation he said:

"I think, marster, I'll go you the Cadogan."

"Aye, that's the gillie. An' I don't mind tellin' you that were it not for the luck o' the last voyage I'd no be able to pay my purchase. But there's fourteen guineas to that pouch an' I'll ha'e me time this night an' sail wi' the tide i' the dawn. Ha'e your duffle but ready an' I'll stop by for 'ee." He placed the tankard to his lips and drank long and deep.

"But," said the lad, "Master Skinner is in bad name along the quays. I heared tell he's a marooner."

"The story's a true one a' that. There's a fine line atween looking for the main chance and goin' on the account and Master Skinner's one who can draw that line. His swivel's never been pointed at any Briton an' never will, if I know my master. It was but last year when one of his company, a Cornishman whose name I no longer recall, lined up nine or ten others with him and demanded the Master go on the account. Master Skinner heared them out and called for a show o' hands. Ten wanted to go pirating and fifteen wanted to see Old Bristol again. So Master Skinner placed the ten in a longboat with one day's provisions and sent them to an island in the Bahamas. There they be to this day, or their bones. There's no fooling with Master Skinner."

"But that shows he be a firm man and one cannot but admire such. I ask only that my first marster be a true man and a brave one."

"Be having your score from that pouch, lad." The sailor took another decisive swig from his tankard and wiped his lips on his sleeve. As he restored the purse to his pocket, it seemed for the moment as if he were about to leave.

"Be in no haste, marster."

"Aye, but there's a wench awaiting me on the High Street and we'll be breakin' bread within half an hour and the laws of good King George in twice that time."

The lad's heart jumped as he saw the man smother a yawn.

"Do you mind if I take my tankard to yon bench?"

The youth smiled his acquiescence. How long, he wondered, would it take the drug to act? And how long would it remain effective? Long enough for him to possess himself of the fat purse. Beyond that he had no plans. He knew, if he thought about it at all, he would have to bolt or else face a charge of robbery; there was none other present who might be made a scapegoat. The sailor found the bench and threw himself down heavily without further attention to his tankard. Slowly his head slumped to his chest and then came a snore, deep and resonant, followed by a complete relaxing of his body.

Silently and with almost catlike cunning the boy came from behind the bar. For a moment he listened at the door that gave on the landlord's room in the rear and then, satisfied that he would not be interrupted from that quarter, continued towards his quarry. For an instant he stood above the sailor and then deliberately kicked one of the outstretched feet to see if any degree of consciousness remained. A grunt was his only answer. Quickly he reached into the pocket containing the purse and his fingers closed around the leathern pouch; cautiously he withdrew them but his inexpert hand was betrayed by nervousness, and when success was all but his he must needs drop it clanking to the floor. As he hurriedly sought to repossess it, he saw the sailor had opened one eye and before he could straighten up the man was upon him.

"How now, my young gossoon? Running a-tick, be you? And no new offender, an old hand, I'll warrant."

The lad easily avoided the clutching hands and stowed the purse in his shirt front.

"Hold now, I say! Let me have my hands on you!" shouted the still groggy man.

The lad's sole thought was to keep out of the way of those tarry, ham-like fists swinging in every direction; one blow of either would have laid him cold upon the floor. He danced about avoiding every attempt to lay hold of him until, unwittingly, he found himself properly cornered. Spreading his arms wide, the big sailor started closing in, and it was only chance that the boy ducked beneath and made a clear escape.

"How now, my bully! I've a trick worth two o' that!"

Once more he closed in on the youth, cornering him this time away from the bar and door and crouching low to prevent another dodge; the boy swung with all his might to the jaw and the heavy sailor went over backwards, losing his balance and stumbling to the floor. The youth let out a strange laugh, a laugh from the belly, and one tinged with neither fear nor relief, but rather triumph. His opponent got slowly to his feet, deciding to make it a real battle, and was met with a rain of blows to the face and body, any two of which should have stopped him in his tracks.

"'Zounds! A fair pair of hands you carry in your pocket. But I'll lead you to the watch yet, my bully."

The boy knew his opponent was slowed considerably by the drug; his only escape from the tarry fists lay in constant action, leaping and feinting, placing a blow wherever he found an opening.

"Stay, now, be still," pleaded the sailor. "Let me but blow you down and have in the watch."

But the boy was not staying to be blowed down. He was intent upon getting near the lantern hanging above the bar; if he could but knock it down he might escape in the darkness. With his body he feinted as if to make for the door then ducked to the opposite direction, but the sailor was not fooled, not completely. As he weaved from one side to the other one of his hairy hands fell afoul the lad's shoulder; fear added agility to the thief's movements and he tore himself from the menacing hand and fell back against the wall, leaving half his shirt in his opponent's clutch. Quickly he tried to cover his breast with his hands but there was too much of the shirt gone and the well-rounded breast lay revealed.

"Hola, by my trow! A wench! A woman!" The heavy mouth went agape, the eyes stared first with unbelief, then with delight. Placing his hands on his hips, the sailor threw back his head and gave voice to a loud and lusty laugh.

"Aye, my own. 'Twas a fine bit of flogging you were in for, I trow, but it's to be a different kind of flogging you'll be getting now. Come, lass, my purse and then to our business. I'll ha'e my way before I call the watch, do mysel' a bonny turn." He held out his hand for the purse and added a single word: "Come!"

The girl, blushing, seeking to cover her breast with the remaining fragment of her shirt, saw the sailor coming toward her and sought to hug the wall. As he neared her she lowered her head and, using the wall as a springboard, hurled herself against his midriff. The hard head caught him in the high stomach and he went down gasping for breath. He saw the youth's shadow pass over his body and then heard the crash of a lantern and hurried footsteps in the dark. A door opened and slammed before he could get his wind back and rise to his feet.

The sailor set up a great hue and cry that brought Moll Read and mine host carrying fresh lanterns, brought the watch and all within sound of his voice. The watch stamped his staff upon the ground and called for silence and the great booby tried to tell of the lad who was no boy but a wench, a cutpurse, if you know, who had made off with his pouch after beating him. The watch listened intently and asked if it was a man or a woman who had beat him and stolen his clink; the sailor said it was neither, but a boy who was to go to sea and whose torn shirt had revealed her a woman. Was it mine host, here, or Moll Read, there, and speak truly? 'Twas neither but a lad who had become a woman, and the watch laughed and so did the crowd. The watch again stamped his staff and demanded silence; then he winked an eye at the proprietor, saying as he turned to go:

"It's a vile brew you sell here. Better be getting back to your berth, sailorman, an' sleep on't. Good night, landlord."

Then he went off into the night and Moll Read and mine host slammed the door in the face of the sailor who had tried to bring disrepute on their honoured tavern.

II

The young cutpurse, her swag safely stowed in her breeches pocket, had snatched a fresh shirt, a leathern jacket and heavy greatcoat from a peg in the passageway and hurried out into the night. On tiptoe she had circled the tavern and taken up a position from which she might observe events without being detected. She had seen the watch come up, followed by idlers, had heard a few words as the door opened and closed, and had seen the watch take his departure and the door slammed in the sailor's face. She knew that no pursuit was contemplated and that the only persons she had to fear were the sailor and her mother. Moll Read would not have tolerated any such invasion of her prerogatives and would have demanded the swag down to the last farthing.

Danger lay in other places. She now had money to purchase a station on Master Skinner's Cadogan, the needed ten guineas to take her on the slave trading venture to Sierra Leone, but should her victim turn up on board her shift would be a short one. If she remained ashore in that fear, the sailor might see her and in pressing his charge make known her true sex to the people of Bristol Town. She thought of Master Martell's sloop, lying out in Bristol Channel, ready to sail on a venture that would not bear too close scrutiny. Had not the sailor said that lacking his purse he would have to ask the occasion of Master Martell? There was danger at every point.

Indecision and the cold night air made her pull her greatcoat closer about her body. The sailor was still standing before the tavern door, muttering imprecations upon the house and its landlord and vowing vengeance. The girl felt she could not move until she had learned his destination or at least the direction he would take. Manifestly, his indecision was as great as her own.

With a final curse for the door he turned and went towards the High Street. As soon as his footsteps had died away, the cutpurse turned in the opposite direction but paused, after a few steps, to let out a hearty laugh. Who was the wench on the High Street who would entertain a penniless sailorman and to what would her honeyed greeting change when she learned her visitor had already been ta'en by a lad who was none other than a wench?

The thief resumed her journey toward the jetty; mayhap she'd learn from a passing sailorman where she might find a berth. Ships stood in the Severn, single riding lights bobbing with the tide. Old Bristol had become a great port since the Navigation Act of Good Queen Anne. Bristol ships and Bristol lads were familiar to every port o' call and a sailorman with a fat purse could easily find a berth, aye and choose his own master.

Arriving at the jetty she paused a moment to take stock of her chances. From the distance she could hear the sailor again hurling imprecations at the door of The Saylor's True Friende and the raucous voice of Moll Read in answer, threatening to call the watch if he continued to annoy honest folk. The sailor, she was sure, had been to see his wench and his frame of mind had not been improved by her reception; soon he would be returning to the jetty. As his footsteps came closer, the young thief looked about her for a place to hide. An upturned smallboat belonging to one of the ships in the roadstead lay but a few paces away. Pitching it over on one side, the girl crawled under and let it roll back. Here she was safe for the moment and could see what happened. The sailor, she judged he was her man by his footsteps, came down the jetty, still muttering and cursing and stamping his feet in a great rage. Her heart stopped as he paused beside the smallboat to kick it but then he quieted down and sat himself on the upturned bottom.

He sat thus for the better part of fifteen minutes, from time to time breaking out noisily and indignantly against the treatment he had received and vowing vengeance. The girl underneath gradually recovered her poise as she realized her victim was ignorant of her proximity. The night was a cold one, but she was used to the rigours of outdoor life and could spend the night where she was without great discomfort. Before long she heard other footsteps coming down the jetty. The newcomer came directly towards the boat under which she was hiding.

"Aye, Master Skinner," said the sailor, rising to his feet. "It's a misfortune I've had, master."

"How, now, Jorgen? A misfortune, eh?"

"Aye, master. At The Saylor's True Friende, the tavern beyond, if you will. A cutpurse fouled my tankard, and made off with my pouch."

"'Tis a misfortune, Jorgen, an' my heart to you. Are you joinin' the Cadogan snow[1]?"

"I would, master, but my purchase was in my purse an' 'tis gone!"

"Then, my man, you're out! You are a fair hand and I'll ha'e to look sharp to find another as good. 'Tis bad at this late hour."

[1] Snow: a large two-masted vessel with a short mizzen mast which was removable. She, the snow, could make fair headway under a trysail.

"But, marster, could I but go wi' the Cadogan an' let my purchase be ta'en by three from the return?" There was a whine in the sailor's plea.

"No. Not at all. What if there be no return? Who's to pay then?" Captain Skinner's voice was harsh and indicated no yielding.

"Please to you, marster." The sailor sank to his knees, his voice rising shrilly.

"Nay, an' that's all," thundered the captain. "'Ere's a shillin' for you, an' get you gone before I call the watch. Off wi' you!"

The sailor got to his feet and accepted the captain's shilling and scuttled off; he had had enough of the watch for one night. When he was alone, the captain sat down on the boat and called for the boatswain who should have been on duty beside it.

"Aye, 'e's another I'll be losin' if 'e's no more wits about 'im than that other."

"Ho, boatswain," he shouted and almost leaped into the Severn when he heard the answer come from beneath him.

"Here, marster," and the boat was tilted to permit a young fellow to emerge. Still on his hands and knees, he continued, "Your mon's drunk an' he told me off to 'wait you, marster."

"'Nother? Take me to the Cadogan snow an' be quick. If they be not there at sailing, we sail wi'out 'em."

"Aye, marster, so I told 'im. 'E said for me to go i' 'is place. 'E was a-spendin' of his purchase money an' I have mine."

There was a pause.

"Make a light," ordered the captain, "that I may see who I speak."

"Nay, marster, I 'ave no light."

"Well, let's have this smallboat i' the water and time enough on the Cadogan snow."

Together they put their hands to the smallboat and in a moment both lowered themselves from the jetty. The youth took the single pair of oars and put his weight against them, sturdily pulling for dear life. Out into the stream shot the boat, the captain shouting directions from the stern. When he had her going as he wanted her, the captain said:

"Your name, lad? Your name and where do you hail?"

"Buttons, worship. Buttons Read, son of Simon Read of good memory."

"Aye, I remember Simon well, a good man, a true one he was, too. An' you be 'is spit, eh? You pull a steady oar. I'll not say the word till I get you under lantern light."

For ten minutes the youth pulled on the oars, never looking about to see the direction, leaving all to the captain. The smallboat grated along the side of the Cadogan and Skinner ordered the lad to make it fast.

Later, on deck and in the glare of a riding light, Skinner looked at his latest recruit.

"Let me feel your muscle. I need none but a strong lad."

The girl flexed her forearm to meet the captain's demands and she helped his decision by pulling the stolen purse from her pocket and jingling it to show she had the purchase money.

"Aye, a sturdy lad and a good sailor, too, I'll trow. If you truly be Simon Read's lad, consider yourself engaged."

"A mercy on you, marster," passing him her purse. "Take what you will."

"Where's your chest, Buttons?" asked Captain Skinner.

"On my back, marster. If you go south to the Guinea Coast, I'll have no need for more."

"Nor will you, but we may go to Tasman's land before we see Bristol Town again."

Buttons did not know it, but this remark was made for the benefit of one lurking in the shadow behind the poop.

"Then I'll make my purchase as we go, marster."

"Look sharp, there, Howell Davis," shouted the Captain to the one in the shadow. "Go below an' remain quiet!"

The man in the shadow disappeared.

"Think twice, lad, those two left behind may be the lucky ones. This cruise may yet end on a length of tarry rope."

"I'll cheat the gallows, marster."

"Aye, if you be Simon Read's spit, you will that. Go below and be quiet."

III

Buttons went below to the forecastle and as she entered a voice greeted her.

"Sime Read's lad, eh?"

"Aye, mate, 'is own spit and blood. An' who be you?"

"Howell Davis, o' Milford Haven. I be second to command. Should any mishap occur to that cuckold above I'd be marster o' the snow. It's a word to you, lad, to 'ware your course. Do I make myself clear, son o' Sime Read?"

"Aye, sir, that you do."

Buttons selected a bunk far from the companionway. Her secret was still her own and with her greatcoat she prepared for sleep. All about her were snoring men, her mates as long as her sex remained undiscovered, but men who upon learning the truth would fall upon her like ravening wolves. She had heard of Howell Davis, the Blackbird of Milford Haven; a dark character feared by all who had had dealings with him yet a good trader and a fearless mate, he was a strict disciplinarian and one needed by Captain Skinner in his dealings with slave merchants.

Even though she had had a hard day and was not afraid of her situation, Buttons found sleep difficult to achieve. She had been far and seen much in her seventeen years, but this was her first voyage as a sailor. Of her own early life she remembered little, but her mother, Moll Read, had been a mouthy piece and able to keep no secrets. What she did know of her early life, when she thought of it, was in the words of her mother, ribald and raucous. She did not like to think of her mother; always since she had been aware she had feared the woman and she knew the woman feared her. From whose loins she had sprung was a mystery to all but Moll and she could be counted on not to tell the truth. That her father had been a seaman was evident. Simon Read, whose name she bore, was a privateer when he took Moll to his mother's cot back of Bristol and said she was his bride. Moll was with child and if Simon was ready to admit it was his, that was enough for the parent. Whilst Simon was still in port a son was born to him and he had bestowed his own name upon the young squaller and then had gone off to sea, admonishing his parent that he had done well by her and expected her to do well by his. Simon's first venture was interrupted by a Spanish ball that carried him overboard and the battle was too fast and furious to permit a search for the pieces.

Moll's grief was short-lived. Within a few months she was again with child. Fearing her mother-in-law's wrath she took what money she had with her son and had journeyed to France. There, as Moll tells it, a daughter who was to be named Mary was born and there it was young Simon was buried. Moll had wished it the other way about, as she often said, but wishes were not always won.

When her money gave out Moll found that France and Flanders were not highly remunerative fields for her line of endeavour and thought to try London. Engaging a passage across the Channel was a coy business and the light and airy widow waited long before she found a master gullible enough to let her share his couch. From birth Mary had worn her dead half-brother's clothes and Moll now found it to her advantage to pass as the mother of a lad rather than the protector of a girl child.

London, too, proved a bad field even for a comely widow and, after several threats to drop the daughter into the Thames so that her harlot's progress might not be impeded, Moll learned that the lot of those without children was no better. Even the finest of the courtesans was compelled to stoop to petty thievery to eke out a living and it was indeed petty thievery. The professionals were highly organized and were not at all abashed at turning an interloper over to the watch and then appearing before the magistrate to make complaint, thereby leading a Thieves' Parade to Newgate Prison. Moll quickly learned that if she was to survive she must beat the professionals at their own game and open up a new field of knavery.

Into this world she introduced her daughter whom she had nicknamed Buttons, making the child an accomplice and doing very well by herself until by her endeavours she had changed the fashions of the nobs and swells. It is not a long story.

It was custom's fancy for the ladies to pile their coiffures high upon their heads, decorating these creations with semi-precious jewels, expensive ribbons and even spending great sums upon the wigs themselves. The dandies were no less vain and met their ladies' modes with jewelled hats and expensive perukes and periwigs. These were high above the reach of the average thief and it was only because of her superior imagination that Moll Read was enabled to prey on them. Secreting her child in a huge basket she lifted the wicker to her head and carefully balancing it walked the streets. At a given signal the child would lift the cover and snatch whatever came to her hand, quickly lowering the lid and remaining quiet. This act, of course, required much practice and could succeed only when done with great speed. Brooches and decorations, wigs, hats and shawls all disappeared into Moll Read's capacious basket and, as the child became more agile and adept, the two were able to go further afield, even to the exclusive Mall.

Soon other thieves purloined the idea and the wary Londoner learned to put little of value upon his head; when necessity compelled him to appear upon the streets in full hair dress, he tied it there with a scarf.

New vigilance on the part of the gulled and competition from those who had adopted her methods forced Moll Read to take up other callings. These were numerous and faulty and none of them brought her the thieves' acclaim and all were but steps toward Newgate and Tyburn. Moll's associates had taught her the necessity of working close to those who could not, for reasons best known to themselves, call the guard; a bit of blackmail was harmful to no one, they argued, and quite profitable to one with imagination. Unfortunately, Moll Read had no knowledge of the misdeeds of the wealthy and was compelled to work closer to home. Indeed, the only person she knew with money was her mother-in-law and in her straits she remembered that her late husband had consigned her and her child to his parent's mercies. With what was left from her thievings she engaged passage on the Bristol coach for herself and three-year-old son.

The old lady gazed upon the child and said:

"He's a fine lad, the spit o' his father. I'll ta'e 'im and rear 'im as m'own, but I'll ha'e no trollop in my cot. Leave the lad nigh me an' I'll gi'e 'im of my own bread and bed. Aye, that I will."

Moll Read would have none of that; there would be nothing in it but grief for her. Tearfully she refused to be parted from her own dear son; if she was not welcome, it could only mean he was not wanted either.

"Go to your trade," stormed the old woman, "but leave Simon's lad to me."

"Nay, mither, I'll not be parted from mine own son."

The old woman was firm until she saw her grandchild being led from the house; then she had both of them back. If Moll would keep her skirts straight and bring no ill fame on the name of Read she should have two crowns a week against the lad's support. Moll tried to wheedle a whole guinea and even came down to two and one, but ten shillings was as high as the old 'un would go and she had to be content with the modest living it would provide. She took a small house on a quiet street and Buttons played with the boys of the neighbourhood. It was several years before Buttons learned the difference between boys and girls; during this period all she knew was that some children wore breeches and some skirties and she was one of the former.

Buttons, as she lay warm in her bunk, thought of these things in her own way and did not let the raucous and ribald manner of Moll enter her reminiscences. It was only ten days gone that she had heard the first of these events recited to the landlord. Moll had gone on to tell of how when Buttons was nine the grandmother had died and the two crowns ceased to come and she had sold her daughter to a French lady as a house-boy. There had been a pause in the telling for the grand laugh of how the French lady had taken it when she learned of the deception, but Buttons could have told them, then and there, that before discovery had come she had deserted her menial post and had joined the army as a powder boy.

Moll Read's story of deception and deceit ended there. Buttons knew that if she were to remain at The Saylor's True Friende Moll would not hesitate to sell her again, either as a boy or girl, to whoever offered the highest price. Indeed, the mother had suggested that the deception was no longer necessary and that Buttons might take her rightful place among the belles of Bristol Town.

"An' a girl 'ere's no worse off than those in Lunnon," she had averred. Indeed, thought Buttons, she was better, by far.

Buttons smiled to herself in the dark of her bunk. Little enough did her mother know of her life after she had left the service of the French lady. For two years the girl had served without distinction with the soldiers of the Crown, accepted as a male and fighting as such. Her comrade had been a youth of eighteen, a comely lad who had taken her fancy and with whom she had shared her blankets. Each night they lay in each other's arms for warmth and camaraderie and all had been well until he had discovered her sex. He was delighted to know he might ameliorate the rigours of the campaign with a mistress, but Buttons would have none of it; marriage it would be or nothing. Her comrade, now deeply in love with her, could deny her nothing and together they appeared before the commandant and asked for permission to marry.

There was great merriment as word quickly spread about the camp that two of the King's men were determined to marry and many came to see the curious couple. Later it occurred to the commandant to inform his wife of the phenomenon and this good woman undertook a little investigation of her own. For purposes of record Buttons was required to resume her right name and to promise to wear feminine apparel at the ceremony; a promise that was broken later when Mary with her lad appeared before the chaplain in nothing but her breeks and jerkin. The commander's gifts were honourable discharges from the service and the initiative in forming a purse to be given the happy couple on which to begin their lives. So generous were their comrades, every friend they had being in the army, that they decided to open a tavern solely for soldiers. The Three Horseshoes they called it and located it at Breda, where it was to stand for over two hundred years, ever a monument to the thirst of military men.

To the young husband the whole affair was a lark and he tended bar while Mary, still in men's clothes since the mystery of bustles and skirts was too great for her, waited on the tables. There was much coarse jesting at the expense of the young proprietor and many attempts by love-hungry soldiers to seduce the young wife. She quickly learned to defend herself with her fists, and many a comrade with decorations for valour found himself lying in a corner of the tavern, while a deft hand removed his score from his pocket.

The tavern was a success from the start and in every way. The couple prospered in love and finance, but the young landlord could not forgo the idea that his duties were a continuation of the wedding party. Toasts he drank with each patron besides taking great joy in watching his wife protect her honour. The strain was too much for his frail years and he succumbed, happily it is said, in his bed beside his wife within six months of the marriage. Mary Read had been made bride and widow in her sixteenth year. She buried her husband in the cemetery outside Breda and started back to Bristol Town to see her mother.

At Calais, whilst awaiting the Channel boat that was to take her to England, she listened to a recruiting speech made by a sergeant of cavalry and, liking his looks and the thought of travelling a-horseback with him, she had enlisted. It had been the sergeant she had liked and not the living with her horse; after a few months she had deserted and resumed her journey Bristolward, the same Bristol from which she was now retreating. She had come with fewer than twenty golden guineas from the proceeds of the sale of The Three Horseshoes, only to be robbed of them by her own mother.

IV

Three days later the Cadogan, outward bound for Sierra Leone and the Guineas, stood off the Scillys. A trim, sleek vessel, white from the shrouds to the water-line, she took the winds gracefully, scudding along like a clean piece of paper before the Southern trades. In her hold she carried a general cargo, manufactured metal wares, woollens, boots and shoes, china from the kilns of Staffordshire, hoops for casks and other goods of interest and necessity to the colonists of the far-flung empire. She was an easy-riding ship, the pride of her master's eye and the only rift was that she was over-manned. Fifteen men could have measured her in any weather but there were that many and ten more, so that Buttons was assigned to the cabin when such a captain rated no such factotum in the usual course.

Buttons' duties were anything but onerous; she had much time on her hands and spent the better part of it playing cards and throwing dice with the men in the forecastle and the aftercastle. Master Skinner had taken his toll from the stolen purse and with the few coins left she was able to wager small sums against needed clothing and equipment. She was no gull at games of chance and her winnings included an extra pair of boots, breeches and stockings, shirts, blankets and mufflers and a chest to stow them in. She was accepted by the crew, easily and completely, sharing their lives and their rough, masculine intimacies. She experienced no great difficulty in concealing her sex from them; most sailors slept in their clothes, removing only their boots and greatcoats and, save in the tropics, keeping well covered at all times. There was a degree of privacy for the individual, a small lazaretto being set aside for the usual ablutions and, far forward, the head.

As the vessel bore southward and the winds became warmer the crew stowed their heavy outer clothing and went about in shirts and breeches, barelegged or in wide, breechy pantaloons. Buttons kept her shirt buttoned to the neck, a device regarded by the others merely as a personal idiosyncrasy. For sixteen years she had worn male attire and it had become as natural for her as for her brother seamen; a woman's garments would have been her undoing.

In her role of cabin-boy Buttons had access not only to the sailors' quarters forward and after, but to the master's cabin and the mate's house, and she early became aware of the formation of certain lines of loyalties. Howell Davis dominated the forecastle and had, secretly, forbade his men having any truck with the afterwatch, Captain Skinner's, of which Buttons was nominally a member. The two officers seldom met on deck; when they did they did not speak save in the line of duty. It was rumoured among the crew that Davis' share in the venture equalled that of the master.

That more was amiss than over-manning would not be apparent to the former powder-boy of the King's Forces in Flanders. There were two swivels, one forward and the other aft, and regular drills were held each morning and afternoon, "for purpose of defence." These small cannon, so mounted that either of them might be trained upon any possible target, might indicate that the voyage was not to be an entirely peaceable one. It took but a single well-directed ball to bring the largest merchantman back on his heels, but Captain Skinner was to trade in dangerous waters, and both he and his chief officer conducted their drills along defensive lines. Buttons, idling before the companionway, could see that Howell Davis' gun was pointed at the captain's cabin as often as at an imaginary enemy. Indeed, when the piece was not in use, it was invariably found to be trained upon the master's quarters.

Once, in an unguarded moment, Captain Skinner said to his cabin-boy:

"Ah, Buttons, m'lad, all's not well aboard the Cadogan. If ye hear aught spoken against your master, do you tell me. Hear ye?"

"Aye, master, that I will."

As far as Buttons could determine there had been no other ears present at the time, yet within the hour, having business in the forecastle, she had passed Howell Davis and heard him hiss in her ear:

"Sime Read's spit's a pimp, I trow."

"Pimp? Nay, Master Howell, a loyal man."

"An' to whom? To 'is father's memory? Or to that pantaloon who calls 'isself captain?"

Buttons had hurried on with her task without answering. She did not care for Howell Davis and if asked, at the moment, whose cause she would espouse in case a decision was demanded would have promptly answered that she had but one master and he was also the Cadogan's.

In the aftercastle there seemed to be less whispering, less hugging the shadows and a more outspoken honesty among that watch. One sailorman had summed up the attitude of his fellows:

"The master's a righteous man and a brave one. Where 'e goes, there go I."

The vessel passed Funchal early in January, but did not put in for water or news, continuing on to the more favourable Las Palmas, in the Canaries. Here the ship hove to and the master called for his smallboat and quartermasters to take him ashore. Another ship's boat was to take in the casks for fresh water. As the master went to the rail he summoned Buttons.

"Arm thyself, lad, and stand fast. Let no man enter my cabin whilst I'm away. No man, whatever his rank or his business."

"Aye, marster," saluted the girl.

Captain Skinner lowered himself into his boat and his crew of four bullies quickly pulled for the shore. As the second boat left with the casks Buttons saw Howell Davis order one of the starboard smallboats to be made ready for his own use, and before the master reached the shore four other bullies were pulling the mate towards Las Palmas, but to another point. Buttons stood guard for two hours before she saw the mate's boat returning and another before the captain's left the shore.

"Send Master Davis to me," bellowed Skinner as he came on deck. The chief officer sauntered up and stood before his master.

"Winter, the pirate, is in these waters, Howell Davis. The scoundrel's ta'en several ships. Do you ken that?"

"Now that you've told me," drawled Davis.

"One report has it he's gone south, another westerly," went on the captain.

"Aye, an' which do you ken? If I know the man I'd say he's gone westerly, the better the hunting," said the mate.

"An' you know him well enough, I'll warrant." He looked levelly and directly into the eyes of the second in command. "I shall continue to the Guineas."

Howell Davis' glance did not waver.

"Aye, master. You did not plan—otherwise. You do not wish to pass Rum Cay again, I take it, master." His voice dropped to almost a whisper: "There were ten men, master, ten who may now be ghosts, living or dead."

"Have done! Enough o' that," growled Skinner. "The Cadogan goes to my pleasure."

"Aye, sir, that I know full well."

"An' for reasons best known to mysel', I'll set her course for the Guineas. Call your watch!"

There was a sinister smile about the hard lips of Howell Davis as he turned to call his men. He gave his commands in a manner satisfactory to the most exacting master, and before night fell Las Palmas was far astern.

What either of the officers had heard ashore was not made known to the cabin-boy. Captain Skinner showed he did not like the news he had had ashore, nor did Howell Davis dislike his information. That the infamous Winter was in these waters meant more to Davis than it did to Skinner seemed apparent. The men in the forecastle received a double rum ration that night and on the following morning Captain Skinner ordered the drills at the swivel guns to be resumed. This time, however, he divided his own watch into two gun crews and ordered Howell Davis to do likewise. If fear of treason dictated this move he did not say it, leaving the impression that one watch might work the ship while the other defended it. If Howell Davis had any misgivings about the master's designs he said nothing and continued his duties with his usual efficiency.

Late in February they dropped anchor off Moyamba, off the Guinea coast, under the protecting wings of a bark flying the Royal Ensign, an eight-gun vessel obviously placed for the protection of all British traders. Captain Skinner ran up his own ensign and called across the water for the latest news. Almost immediately a smallboat put out from the warship and rowed towards the Cadogan, seemingly a gesture of courtesy. Captain Skinner, in his best silk breeches and a small sword at his side, went to the rail to greet his visitor. Buttons, standing discreetly behind her master, observed that every one of the stranger's eight guns was manned and that the men on deck all carried muskets.

As the smallboat came within speaking distance the eight-gun bark quickly hauled down the Royal Ensign and ran up in its stead the dreaded Black Peter, the skull and cross-bones in red on a black field. A shot was fired across the Cadogan's deck to enforce the new ensign's mandate.

"Man the swivels, afterwatch!" cried the master. "Load and prepare to fire." After a moment's pause, he ordered, "Fire!" But no shots answered the pirate's shot. Buttons ran from her post at the aftergun to announce to her master:

"The swivels are spiked, marster."

"Place Howell Davis under arrest," began the Captain, but his order was cut short by one from the smallboat.

"Snow Cadogan! Stand and deliver!"

Skinner lifted his two hands high above his head to show he was unarmed and planned no further defence of his ship. The smallboat brushed the side of the snow and the officer and six men leaped to the Cadogan's waist. The pirate officer barked a single order:

"Below, men, and search."

Turning to Skinner he said:

"Who are you and what do you carry, mister?"

Captain Skinner gave his name and stated his cargo, adding that he was here for a bit of trading on his way to Boston Town where he was engaged to carry masts for His Majesty's Navy.

"You be Captain Winter, I take it," said Skinner.

"Nay, mister. England's my name, i' the sarvice of Captain Winter. I was told there was one Howell Davis, a Welshman, in your company."

Howell Davis stepped forward.

"I be he," he announced, proudly.

"Captain Winter bespoke my mercy for you, but I do not care for your face," said England. "To your station."

"Master Davis is a traitor and under arrest," said Skinner. "For spiking yon swivels."

"I would a word wi' you, master," said Davis to the pirate. Howell Davis spoke in whispers to Captain England, who, from time to time, nodded his acquiesence. When Davis had finished the pirate said:

"Nor do I care more for your voice, now, fellow. To your station and take your chances wi' the rest."

Howel Davis seemed to be on the point of sinking to his knees to plead his cause, but thought the better of it and obeyed the order.

Captain Skinner stood alone and unregarded with only Buttons at his side. One of the pirate's men came up to the master and thrust a hairy face into that of the captain.

"How, now, mister! Do you not recognize me? An' Jeems 'ere, an' Toby there. Aye, that you do, I can see. Eh, Toby, 'ere's our artful marster who marooned us on Rum Cay. What serves us must sarve im. Eh, Jeems?" He spat full and plentiful into Skinner's face.

"'Ere, now, none o' that!" called Edward England.

"'E's our pleasure, marster. 'E did us a turn last year an' now's come ours. Eh, mates?"

"'Ear! 'Ear!" called both. Then all three fell upon their former captain and bore him to the deck, pummelling him and rending his clothes.

"'Ere, now," said the first speaker. "Let's have 'im right. To the capstan, mates!"

In a moment they had dragged the unfortunate man to the windlass and triced him to it. One of the men who had gone below to search came on deck with his arms filled with bottles of rum. These he passed to the three who were tormenting and humiliating the Cadogan's master.

"Back to the bark an' bring the others," ordered the spokesman. "This is their fun as 'tis ours."

One man detached himself from the mêlée and went to the smallboat.

"Out o' the way, lad," said the bottle bearer to Buttons, "an' mind your 'ands."

Buttons would have liked to help her master, but as none of the men of her own watch lifted their hands she could not do otherwise than follow their example. Howell Davis' watch stood apart, as if detached from the whole spectacle.

The men about the Captain broached several bottles and passed them around. The pirates lost interest in everything save the rum, and their captain, in and out of the master's cabin, was busily completing his survey of the prize.

"Aye, Skinner, and how to you. How's Bristol Town and Moll Read? Would you like a dram o' your own fine rum?"

Shortly thereafter the smallboat returned with the other men who had been marooned on Rum Cay and more bottles were brought up and passed about. Each of the newcomers passed Skinner offering him some new indignity and injury. The crew of the Cadogan were now sharply divided into two camps, the one laughing uproariously at the antics of their captors, the other sullenly defiant and helpless. The latter knew only too well that at the first sign of resistance their heads would pay the cost and they obeyed on the double every order uttered by any pirate.

Captain England ordered the crew of the Cadogan to assemble on the poop just as one of Skinner's tormentors hurled an empty bottle at the unfortunate man's head, hitting him above the eyes. Buttons hesitated a moment and found herself urged along by a kick from one of the pirate crew. When the crew was mustered aft England looked them over carefully, studying their faces and physique, and examining the garments they wore. He looked so long and intently at the cabin-boy that Buttons, for the first time, feared that her sex would be discovered and the thought sent a cold chill over her. But the inspection ended without further comment.

"Now, m'hearties," said England. "I'll have you know with whom you're dealing. I am Captain Edward England, in the sarvice of the dread Captain Winter. We are on the account and in yon bark lies the booty o' many a proud ship. Who amongst you wants to join our company? It's an easy way an' there's no standing watch, no labouring when you do not feel for it. There is rum for all and in great plenty. Come, m'hearties, decide quickly."

One man stepped forward. He was Howell Davis, of Milford Haven. A look of distaste and displeasure passed over the pirate's face, but his voice did not betray him.

"Aye, the first," shouted England with the forced enthusiasm of a recruiting sergeant. "Who'll follow this brave man? I make him captain of this sloop and the very next shall be the mate. Come, quick, hearties."

One by one the men of Howell Davis's watch stepped up beside the head of their crew.

"Twelve in all. We need three more," announced England.

At this point the attention of all was drawn to the plight of Captain Skinner by a scream. His tormentors were now breaking the empty bottles before they hurled them at him and his face was already bleeding from a dozen gashes. One pirate was drunkenly chanting:

"If I swing by a string

I will hear the bells ring,

An' that will be the end o' poor Tommy."

Buttons had heard Moll Read sing it often, the song of the thieves of London. She was sure that were Moll here on the Cadogan's deck she would become one of the cut-throat crew.

Now the pirates about the captain were on their feet, circling about the almost unconscious master, throwing rum into his wounds and tearing aside his shirt to make a larger target for their missiles. Above the din they made Buttons could hear Skinner's groans and screams of pain.

"We are," went on England boastfully, "on the grand account. With these two ships and all you brave bullies we go to take the Don, a Spanish ship. On the Don are many beautiful wenches, Spanish ladies the like o' which would not talk to you men, and these brave lads who have already joined shall have first choice. Come, decide quickly. A warm Spanish lady for each man o' you. Plenty o' fine Spanish wines and brandies to quicken your pulses, and rum, too, for them as likes it."

England, for a moment, watched his men torturing the master. Sotto voce, he muttered: "Aye, there go the fine breeches and the sword that I'd picked for mysel'."

Buttons shivered again at the thought of the Spanish women who would be thrown to these fellows and of her own fate at their hands should her sex be revealed. No, she would not risk discovery by joining them. Far better to be marooned and to take her chances with the men she knew. She was, she knew, the match of any man aboard the Cadogan so she would cast her lot with them.

The men torturing her captain had now joined hands and were dancing a saraband about their almost unconscious victim, singing a bawdy street song. One called for music and forgot it the next breath, others cried for rum and these did not forget.

"Have done, down there," shouted England. "Do you hear?"

"Aye, marster." The singing and dancing were silenced and the men applied themselves to their bottles.

"Fine clothes and much gold shall be ours. When we take a rich ship anything you see is to be yours, even to the captain's breeches or his shirt. Take what you will and all gold doubloons are to be divided, so and so, according to station. Eh, you there, lad. Come join us and the youngest virgin shall be yours, the finest breeches and silken shirts. Hey, now, what say?"

But Buttons' eyes were on her former master. She saw the pirates put their heads together and talk in tones too low to be heard. Then one of them detached himself from the crowd and went to the captive.

"'E was a good marster, 'e was, for all 'is bad ways, and I'll not see him done wrong. 'E's entitled to an 'onerable death and I propose to give it him." The speaker drew a pistol from his belt and examined the priming and set a match to it. Then, quite deliberately he took hold of the captain's nose and lifted it high until the torn and bleeding mouth gaped awide. Then he shoved the pistol as far into the captain's throat as it would go and awaited its firing. When his task was finished he turned to his mates and said:

"Aye, 'e was a good marster according to 'is lights and 'e dies like the brave man 'e was." A loud cheer greeted his announcement.

There was a retching sensation in Mary Read's stomach, the first she could recall; she was cold and sweaty behind her knees and she wished she were back in Bristol Town, even though it meant Moll Read's questionable protection. She had seen violent death often enough, but nothing approaching the barbarity of these pirates. A thousand maroonings would she choose before she would join with them.

Captain England turned from the gruesome spectacle with a laugh.

"That, m'hearties, is how we treat with traitors."

The pirates who had tortured Captain Skinner now turned to other interests and Buttons saw one of the Bristol men who had steadfastly refused to join the corsairs pulled down from the poop and stripped of his clothes. Clothes, she learned, were in demand among the picaroons and considered a part of the prize. The naked man hurried to hide behind the shadows and the pirates, sensing more fun, were after him and belabouring his hide with their cutlasses.

Howell Davis, now designated captain of the Cadogan, stood beside England, who turned on him.

"I tell you, Davis, I've no stomach for a man who'll not fight for his vessel, come what may. But Captain Winter knows you for the traitor you are and I can only obey my master's orders. You have but twelve men to sail the sloop, can you manage?"

"With such a twelve I can," answered Howell Davis.

"Last chance," announced Edward England, "to join with my brave lads. Last chance!"

But no other Bristol man, none from the afterwatch, came forward and in a burst of temper the pirate chief shouted:

"Very well. Every one of you strip to the buff; my men need your garments."

An anguished look crossed Mary Read's face. It was only by keeping hold of herself that she was able to save herself from fainting.

I

Mary watched her shipmates of the Cadogan as they began removing their clothes. A blush crept to her cheeks and her heart sickened with a great fear as she began unbuttoning her jerkin. Indeed, one of the pirates from the Sparrowhawk was already before her, one hand grasping the hem, ready to claim it for himself. Abruptly she pushed the man aside and placed herself before Captain England.

"I'd like to join you on second thought, marster, but I want no part of yon yellow bastard, Howell Davis by name. I'd like to go along wi' you in the Sparrowhawk." She had some difficulty in keeping her voice from betraying her sex.

"Ah," laughed England, regarding Buttons appraisingly, "a lad o' fine bottom. Nor would I consent to serve under one who stinks as he does. Get your chest, lad, and wait me near the cockboat." Turning to the new master of the Cadogan, he went on: "More's the pity you could not hold the loyalty o' such a lad, Davis."

"A snipe, and useless among birds of prey," said Davis.

England watched the crew gingerly removing their clothes.

"What do you do with these others?" he asked.

"I be o' two minds, mister. The first be to silence for ever their tongues lest they return to Bristol and inform against me. The other be to sarve them as Skinner sarved his men, maroon them. What think you?"

"I think as Captain Winter directs, as any loyal man would. To my mind these twelve who refuse to go on the account with you are too valuable to be wasted either in death or marooning. Captain Winter did not speak his mind about manning the Cadogan snow and I may not be exceeding my orders if I place on your decks the very men that Skinner marooned. Aye, 'tis a good idea. You saw how they did for him? Aye, I shall do it, damme! It will sarve you as a constant reminder o' the way o' traitors and hold you to the mark o' honour. Those of your watch will man the snow with the lads from Rum Cay."

The pirate chief turned to the naked men and summoned them before him. Each of them, seeking to cover his exposure with his hands, obeyed with alacrity.

"Here's another chance for you men. I do not question whether you act from unwillingness to go on the account wi' us or from your dislike of Mister Howell Davis. That be your own thought and no man can take it from you. Let it be known that, speaking as I am for the gallant Captain Winter, none shall pay wi' his blood; the worst that can befall you will be marooning and at as convenient a place as our activities will permit. If any of you wish to follow the brave lad nigh the cockboat and join us i' the Sparrowhawk he may enter the company wi' a full share and receive his clothes and gear. Now, what say you, my merries?"

Three men reconsidered and held up their hands. The others, ten in all, held to their purpose, preferring to be marooned on a lonely shore without clothes to cover them or food for their bellies, strangers on a more strange strand. But these were Bristol men and Bristol men were of their own minds. And they were true.

Howell Davis' hand went to his newly acquired cutlass and he made as if to unsheath it and lay about among these men who held to their own opinion. Edward England smiled at him mockingly; it seemed to those who watched the two men that the pirate wished Howell Davis might commit an overt act so that he might rid the sea of him.

The three who had reconsidered were getting into their clothes and the ten nude men were ordered to uncover the hatches and prepare to tranship the goods wanted for the Sparrowhawk, to lower and man the smallboats. Already their shoulders were beginning to show the effects of the Guinea Coast sun and England hoped its rays would compel some of them to change their stout minds.

Buttons got her first lesson in piracy then and there. An impulse to aid in uncovering the hatches was met by a sharp command to stand aside. Then it was explained to her that while prisoners were on board all menial tasks were done by them, that those who elected to throw their lot with the pirates were spared all unnecessary labour.

Two of the pirates were told off to sew the remains of Captain Skinner in sailcloth and to bury them with whatever ceremony they thought fit.

England carried on his inspection of the cargo of the snow and those articles he needed or could find use for were sent on deck; cases and casks of wines and liquors, clothing, boots and shoes and much of the Staffordshire ware. Then, selecting two men from his own crew, the pirate went to the former master's cabin and looted it of everything of value. Skinner's little leathern case, copper-bound and brass-locked, containing his purchase money was among the things he took. An hour later England stood on the quarterdeck with Howell Davis.

"Make up your company, Davis, and have them sign the articles. Your share of the loot will be carried to Captain Winter. There are enough goods on board for you and your crew. At dawn to-morrow ship your anchor and make for Mariaguana, in the Bahamas, and report to Captain Winter. I'll expect you there when I arrive; I go by another route. That is all, sir."

Howell Davis saluted and saw his superior to the cockboat. Edward England, whether from contempt or a mere lack of interest, did not look back after giving the order to cast off.

Buttons' first taste of piracy seemed scarcely as terrible as she had imagined. Save for the murder of Captain Skinner, which had little or nothing to do with the actual act of piracy, she had seen no violence save the stripping of the members of the company. Edward England was, by her way of taking stock, a far better man than Howell Davis and she felt she might find him an even better master than Skinner. She saw that he was observing her closely.

"I'd make ye my cabin-boy but you seem bully enough to go on your own and I have a boy to do for me. What manner o' man is this Howell Davis? Know you him well?"

"Nay, marster; but that we were shipmates I'd not know him at all. An unsavoury fellow to my mind, sir."

"I saw to that. Well, he's his orders and if he fails to report to Captain Winter, it's none o' my concern. You will go in the first watch. Know you the cutlass?"

"Nay, marster, only the sabre. But with that my right arm is a true one."

The bark was a large, commodious vessel and, like all her kind, heavily overmanned. Buttons was consigned to the forward castle where she found the bunks wide and comfortable with the booty from many vessels. Seeking one still unoccupied, she was informed that the crew slept two to a bunk and that she would have to share with one of the older men.

"What! Better far a marooning than to lay the night through with one o' you."

"'Tis bonny i' these waters, lad, the nights be that chill."

"I lay on the deckhead then," decided Buttons. "Methinks you want for a touch o' water." She wrinkled her nose in distaste. At that moment a young fellow of twenty entered, a blond chap of cleanly habits who seemed to find as much to dislike in the forecastle as she. Buttons appraised him by and large and said, "I might share a bunk with yon lad."

The young fellow looked at her closely. Then, pointing his finger, he said:

"Yon bunk's mine. Stow your gear, lad."

"What's your name, mate?"

"Jones, and none other. Seaman Jones. An' yours?"

"Buttons Read, the bloody spit o' Sime Read, a man for men and beyond the ken o' these."

Buttons stowed her stuff, roughly tossing it into the bunk, and then swaggered out on deck. She wanted to seek another place to lay her head before Jones could discover her imposition. The naked men from the Cadogan were busily scrubbing the decks, urged on by pricks from the boatswain's cutlass. All about her was an air of expectancy; men lolled about the deck looking hungrily at the quarterdeck and cabin. Then the boatswain forgot his charges and blew a shrill blast on his pipe, summoning all hands to the mainmast. Captain England, supported by three other officers, appeared on the quarterdeck and held up his hand for silence.

"Four new men to our goodly company. One has been sent to the forward watch, the other three to the after. As soon as the prize is distributed they will report to the mate and sign the articles. The prize, Cadogan snow, out of Bristol, taken this morning, yielded but a small quanto of rum and wines and some eleven hundred guineas. One half to our gallant master and his humble servants, the balance share and share alike to one and all you brave lads. Five golden guineas and a fine bottle o' rum for each."

The men formed in line and accepted their share of the prize, jingling the gold coins in their hands and holding the rum against the sun to determine its quality and strength.

In the forecastle Buttons sold her rum to another for a guinea and then brought out her dice. The stakes were larger than she was accustomed to playing for but this was due to the lack of small coins among the crew. She won steadily, forgetting the noon meal in her ardour for gaming and pausing only to take a swig of the bombo that was being passed about.

At the evening meal she remembered she had not located a place on deck for sleeping and went about seeking it at once. But on the Guinea Coast the night descends like a blanket and the deck was dark. Then her boatswain ordered her on watch. Though she was tired from the day's excitements, Buttons was glad to accept the duty. When she came forward at midnight her bunkmate went on and, for the first night at least, her problem was solved.

But not entirely. She threw herself on the bunk and fell asleep almost at once. When she awoke her bunkmate was already off duty and was snoring his head off beside her. Buttons managed to get in a few more winks before it was time to rise. To her great pleasure and relief she found that Jones suspected nothing, but she resolved to find that spot on deck before another night.

II

Buttons was early ordered to the crow's nest, high above the crosstrees of the topgallant, to scrutinize the horizon. To the east was green Africa; after that only the Cadogan snow broke the slender threadlike line over which came prey and danger alike to such as she now was. A bright lookout was kept on any ship but the man in the pirate's crow's nest was picked for alertness and clarity of vision. And the long glass Buttons held in her hand could send that horizon far distant or bring it close. She swept it again and again with her glass and then put it up.

Below her on the deck men were struggling with the anchors. In a minute they would be flocking to the rigging, all about her, above and below. Across the narrow strip of water she saw Howell Davis on his quarterdeck and wondered, curiously, how long he would tread it. She heard England's order to unclew the sails and make fast and ten minutes later the Sparrowhawk was running before the wind, on a course south by west, the little sunburnt town of Moyamba dropping quickly behind. Soon the town itself was out of sight; soon, too, the Cadogan was hull down on the horizon, following truly the course set for it by Captain England.

At noon Buttons gave up her post to her bunkmate, a little saddened that he went on duty as she came off, but happy in knowing that by such an arrangement she could have the bunk safely to herself. She went below to get her pannikin and then to the galley for her food, a composition of dried meat, beans and grain, all cooked together, and a handful of hard ship-biscuit. She ate the unsavoury mess, liking the pirate life less than ever. Seeing her dislike for the food, one of her mates assured her that in the evening they would have a rare treat of conkie, a soup made of conch clams.

Two whole days' journey down the African coast the Sparrowhawk hove to and the prisoners were ordered to the boats to be marooned on the shore. Captain England gave them one more chance to join up but none accepted the offer and Buttons, watching them from her station aloft, knew that if it had not been necessary to expose her body, she would now be with them. Five prisoners and four pirates to each boat, a few bottles of water and a bag of ship-biscuit. It was only half a league to the shore but the pirates would go no further than necessary; the prisoners could swim the rest of the way. The spot had been picked for its loneliness.