* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Florence Vol 1 of 2

Date of first publication: 1901

Author: Grant Allen

Date first posted: Sep. 12, 2014

Date last updated: Sep. 12, 2014

Faded Page eBook #20140917

This eBook was produced by: David Edwards, Ron Tolkien & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

| Travel Lovers’ Library | |

|

Each in two volumes, profusely illustrated |

|

| Florence | $3.00 |

| By Grant Allen | |

| Romance and Teutonic Switzerland | 3.00 |

| By W. D. McCrackan | |

| The Same.—Unillustrated | 1.50 |

| Old World Memories | 3.00 |

| By Edward Lowe Temple | |

| Paris | 3.00 |

| By Grant Allen | |

| Feudal and Modern Japan | 3.00 |

| By Arthur May Knapp | |

| The Same.—Unillustrated | 1.50 |

| The Unchanging East | 3.00 |

| By Robert Barr | |

| Venice | 3.00 |

| By Grant Allen | |

| Gardens of the Caribbees | 3.00 |

| By Ida M. H. Starr | |

| Belgium: Its Cities | 3.00 |

| By Grant Allen | |

| Rome | 3.00 |

| By Walter Taylor Field | |

| Romantic Ireland | 3.00 |

| By M. F. and B. McM. Mansfield | |

| China and Her People | 3.00 |

| By Hon. Charles Denby, LL. D. | |

| Cities of Northern Italy | 3.00 |

| By Grant Allen and George C. | |

| Williamson | |

| L. C. PAGE & COMPANY | |

| (INCORPORATED) | |

| New England Building | |

| Boston, Mass. | |

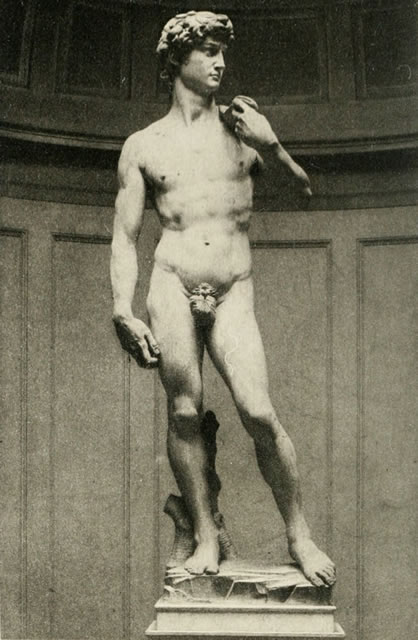

MICHAEL ANGELO.—DAVID.

The object and plan of this book is somewhat different from that of any other guides at present before the public. It does not compete or clash with such existing works; it is rather intended to supplement than to supplant them. My purpose is not to direct the stranger through the streets and squares of an unknown town toward the buildings or sights which he may desire to visit; still less is it my design to give him practical information about hotels, cab fares, omnibuses, tramways, and other everyday material conveniences. For such details, the traveller must still have recourse to the trusty pages of his Baedeker, his Joanne, or his Murray. I desire rather to supply the tourist who wishes to use his travel as a means of culture with such historical and antiquarian information as will enable him to understand, and therefore to enjoy, the architecture, sculp[x]ture, painting, and minor arts of the towns he visits. In one word, it is my object to give the reader in a very compendious form the result of all those inquiries which have naturally suggested themselves to my own mind during thirty-five years of foreign travel, the solution of which has cost myself a good deal of research, thought, and labour, beyond the facts which I could find in the ordinary handbooks.

For several years past I have devoted myself to collecting and arranging material for a book to embody the idea I had thus entertained. I earnestly hope it may meet a want on the part of tourists, especially Americans, who, so far as my experience goes, usually come to Europe with an honest and reverent desire to learn from the Old World whatever of value it has to teach them, and who are prepared to take an amount of pains in turning their trip to good account which is both rare and praiseworthy. For such readers I shall call attention at times to other sources of information.

The general plan pursued will be somewhat as follows. First will come the inquiry why a town ever gathered together at all at this particular spot—what induced the aggregation[xi] of human beings rather there than elsewhere. Next, we shall consider why this town grew to social or political importance and what were the stages by which it assumed its present shape. Thirdly, we shall ask why it gave rise to that higher form of handicraft which we know as Art, and toward what particular arts it especially gravitated. After that, we shall take in detail the various strata of its growth or development, examining the buildings and works of art which they contain in historical order, and, as far as possible, tracing the causes which led to their evolution. In particular, we shall lay stress upon the origin and meaning of each structure as an organic whole, and upon the allusions or symbols which its fabric embodies.

A single instance will show the method upon which I intend to proceed better than any amount of general description. A church, as a rule, is built over the body or relics of a particular saint, in whose special honour it was originally erected. That saint was usually one of great local importance at the moment of its erection, or was peculiarly implored against plague, foreign enemies, or some other pressing and dreaded misfortune. In dealing with such[xii] a church, then, I endeavour to show what were the circumstances which led to its erection, and what memorials of these circumstances it still retains. In other cases it may derive its origin from some special monastic body—Benedictine, Dominican, Franciscan—and may therefore be full of the peculiar symbolism and historical allusion of the order who founded it. Wherever I have to deal with such a church, I try as far as possible to exhibit the effect which its origin had upon its architecture and decoration; to trace the image of the patron saint in sculpture or stained glass throughout the fabric; and to set forth the connection of the whole design with time and place, with order and purpose. In short, instead of looking upon monuments of the sort mainly as the product of this or that architect, I look upon them rather as material embodiments of the spirit of the age—crystallisations, as it were, in stone and bronze, in form and colour, of great popular enthusiasms.

By thus concentrating attention on what is essential and important in the town, I hope to give in a comparatively short space, though with inevitable conciseness, a fuller account than is usually given of the chief architectural[xiii] and monumental works of the principal art-cities. Whatever I save from description of the Cascine and even of the beautiful Viale dei Colli (where explanation is needless and word-painting superfluous), I shall give up to the Bargello, the Uffizi, and the Pitti Palace. The passing life of the moment does not enter into my plan; I regard the town I endeavour to illustrate mainly as a museum of its own history.

For this reason, too, I shall devote most attention to what is locally illustrative, and less to what is merely adventitious and foreign. I shall deal rather with the Etruscan remains, with Giotto and Fra Angelico, with the Duomo and the Campanile, than with the admirable Memlincks and Rubenses of the Uffizi and the Pitti, or with the beautiful Van der Goes of the Hospital of Santa Maria. I shall assign a due amount of space, indeed, to the foreign collections, but I shall call attention chiefly to those monuments or objects which are of entirely local and typical value.

As regards the character of the information given, it will be mainly historical, antiquarian, and, above all, explanatory. I am not a connoisseur—an adept in the difficult modern[xiv] science of distinguishing the handicraft of various masters, in painting or sculpture, by minute signs and delicate inferential processes. In such matters, I shall be well content to follow the lead of the most authoritative experts. Nor am I an art-critic—a student versed in the technique of the studios and the dialect of the modelling-room. In such matters, again, I shall attempt little more than to accept the general opinion of the most discriminative judges. What I aim at rather is to expound the history and meaning of each work—to put the intelligent reader in such a position that he may judge for himself of the æsthetic beauty and success of the object before him. To recognise the fact that this is a Perseus and Andromeda, that a St. Barbara enthroned, the other an obscure episode in the legend of St. Philip, is not art-criticism, but it is often an almost indispensable prelude to the formation of a right and sound judgment. We must know what the artist was trying to represent before we can feel sure what measure of success he has attained in his representation.

For the general study of Christian art, alike in architecture, sculpture, and painting, no trea[xv]tises are more useful for the tourist to carry with him for constant reference than Mrs. Jameson’s “Sacred and Legendary Art,” and “Legends of the Madonna.” For works of Italian art, both in Italy and elsewhere, Kugler’s “Italian Schools of Painting” is an invaluable vade-mecum. These books should be carried about by everybody everywhere. Other works of special and local importance will occasionally be noticed under each particular city, church, or museum.

Wherever in the text paintings or other objects are numbered, the numbers used are always those of the latest official catalogue. Individual works of merit are distinguished by an asterisk; those of exceptional interest and merit have two asterisks.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

|

|

Introduction | ix | |

| I. | Origins of Florence | 1 | |

| II. | Santa Croce and the Franciscan | ||

| Quarter | 10 | ||

| III. | The Sacristy and the Chapels | 24 | |

| IV. | Santa Maria Novella and the First | ||

| Dominican Quarter | 38 | ||

| V. | The Spanish Chapel | 59 | |

| VI. | The Old Cathedral | 73 | |

| VII. | The New Cathedral | 94 | |

| VIII. | The Second Dominican Quarter: San | ||

| Marco | 111 | ||

| IX. | The Fra Angelicos of San Marco | 123 | |

| X. | The Belle Arti | 141 | |

| XI. | The Halls of Perugino and Botticelli | 154 | |

| XII. | The Tuscan Galleries | 175 | |

| XIII. | The Hall of Fra Angelico | 199 |

| PAGE | |

| Michael Angelo.—David (see page 151) | Frontispiece |

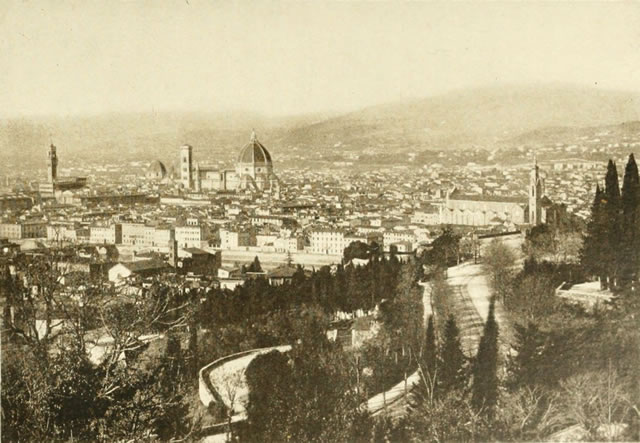

| General View of Florence | 6 |

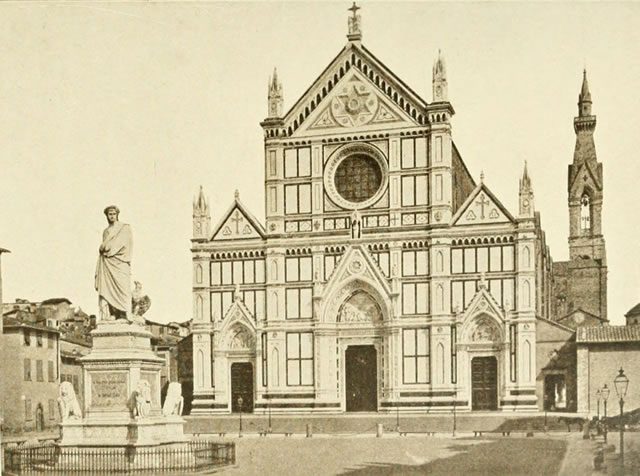

| Church of Santa Croce and Statue of | |

| Dante | 12 |

| Interior of Santa Croce | 16 |

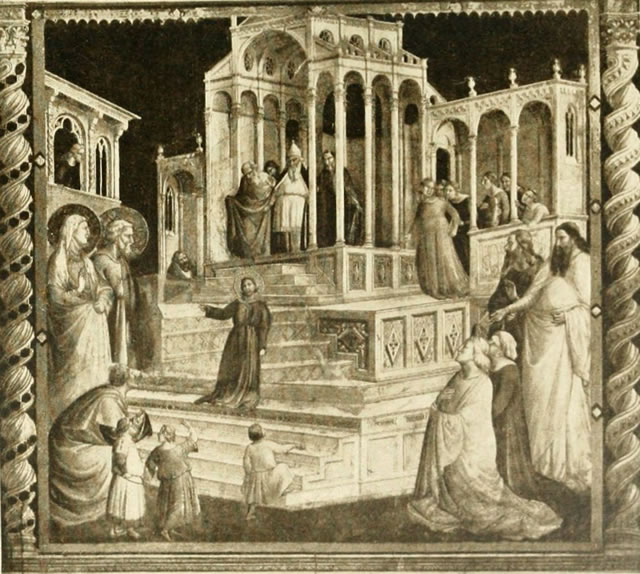

| Taddeo Gaddi.—Presentation of the Virgin | 19 |

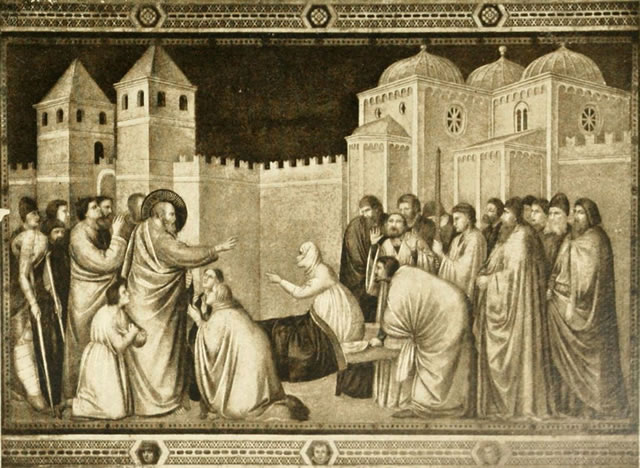

| Giotto.—Raising of Drusiana | 28 |

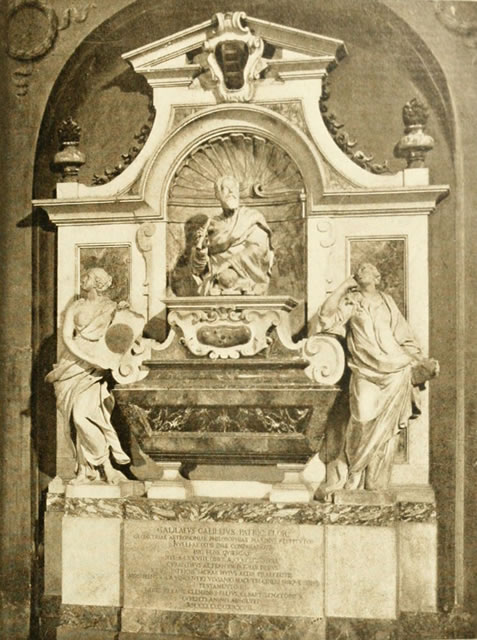

| Tomb of Galileo Galilei | 34 |

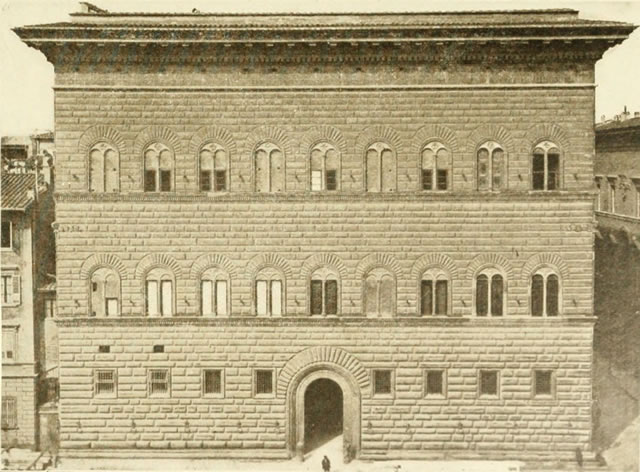

| Strozzi Palace | 39 |

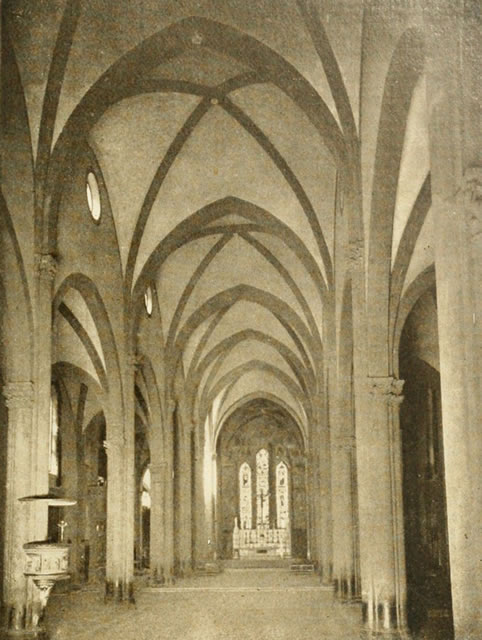

| Interior of Santa Maria Novella | 44 |

| Filippino Lippi.—Raising of Drusiana | 48 |

| Ghirlandajo.—Birth of John the Baptist | |

| (Detail) | 53 |

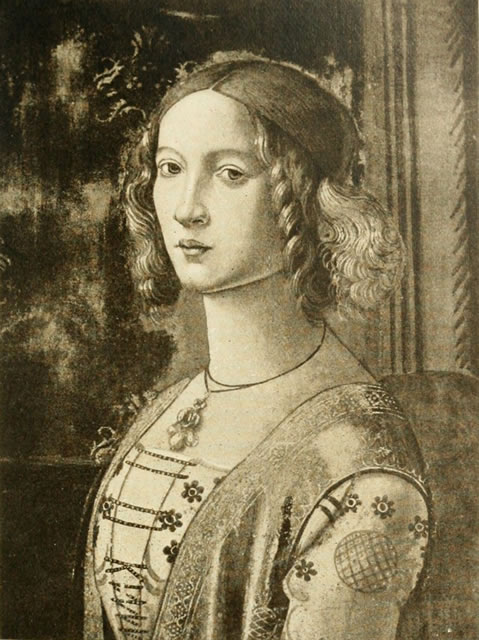

| Green Cloister in Santa Maria Novella | 61 |

| Simone Martini.—Church Militant (Detail) | 64 |

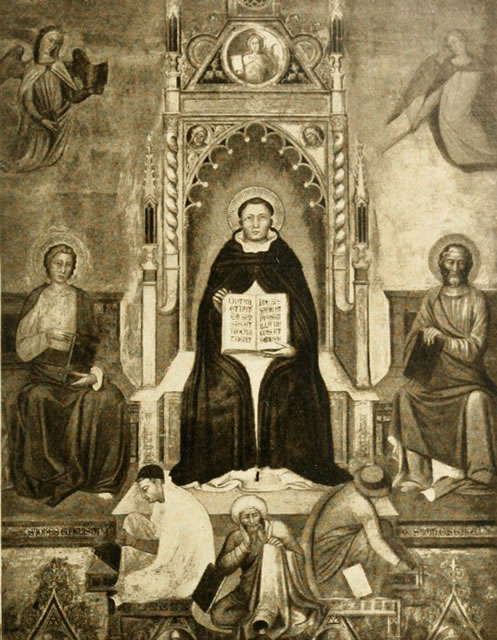

| Taddeo Gaddi.—Glory of St. Thomas | |

| Aquinas (Detail) | 68 |

| [xx] | |

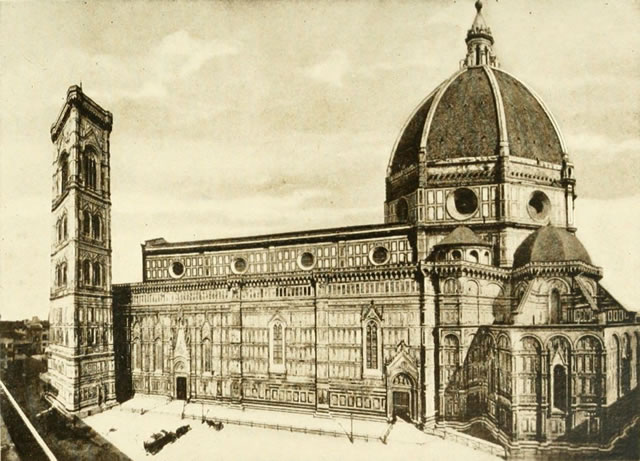

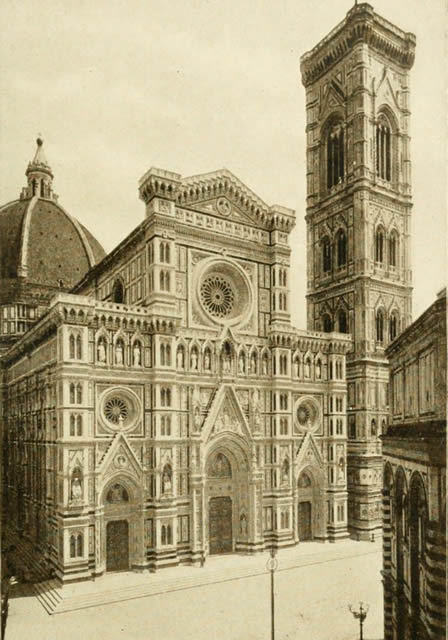

| The Cathedral | 76 |

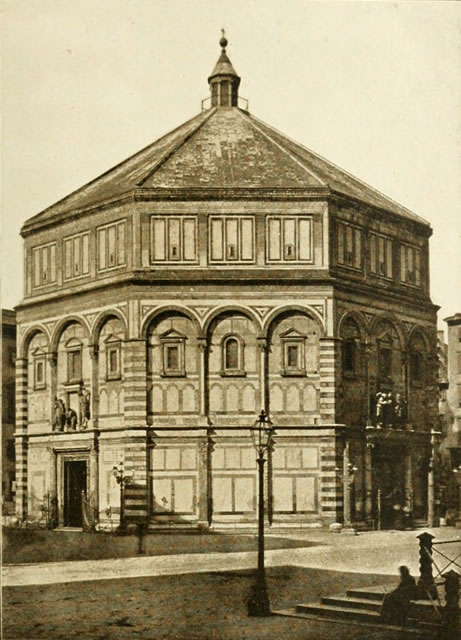

| Baptistery | 80 |

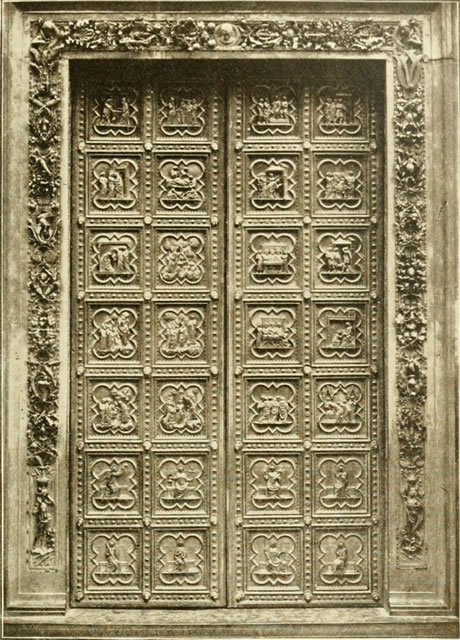

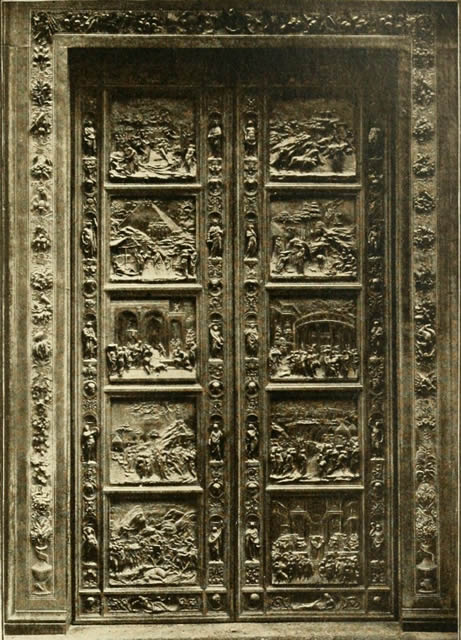

| Andrea Pisano.—Bronze Doors of the | |

| Baptistery | 82 |

| Lorenzo Ghiberti.—Bronze Doors of the | |

| Baptistery | 88 |

| Façade of the Cathedral | 94 |

| Interior of the Cathedral | 99 |

| The Campanile | 110 |

| Piazza and Church of San Marco | 114 |

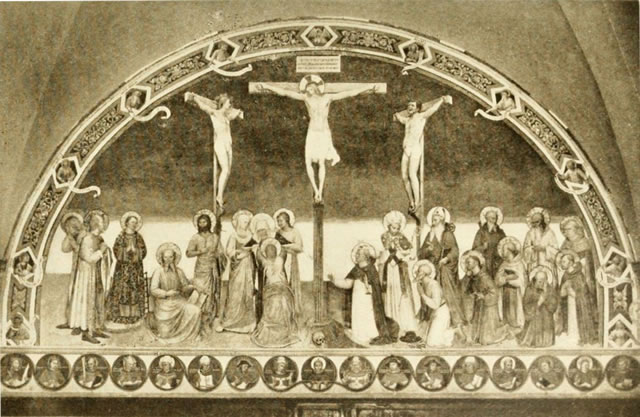

| Fra Angelico.—Great Crucifixion | 116 |

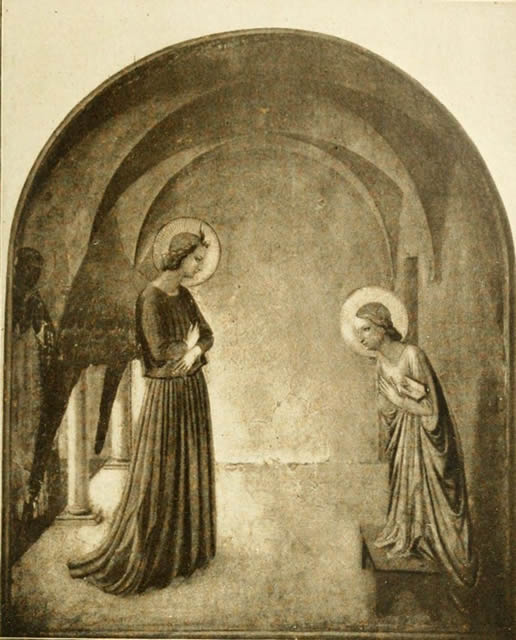

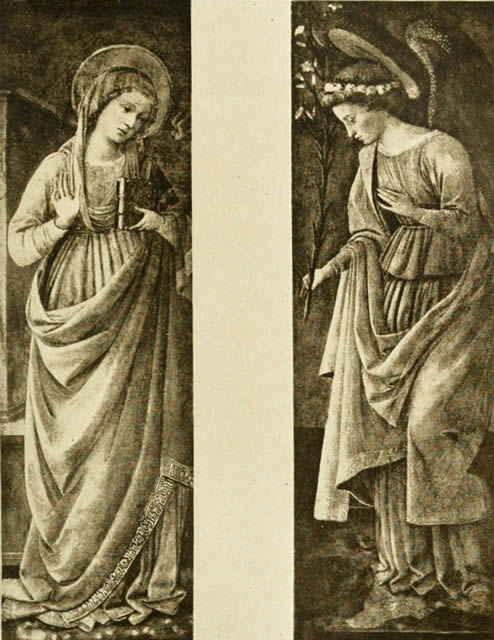

| Fra Angelico.—Annunciation | 124 |

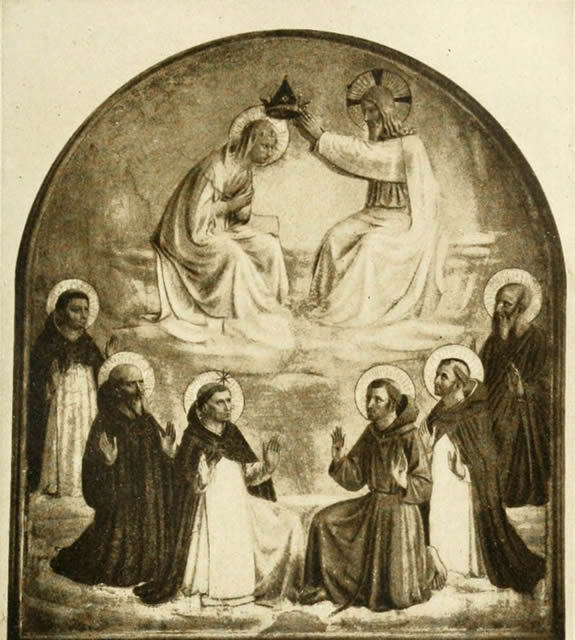

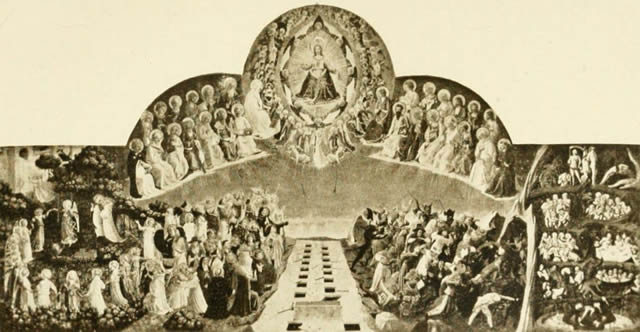

| Fra Angelico.—Coronation of the Virgin | 128 |

| Benozzo Gozzoli.—Portrait of Lorenzo | |

| the Magnificent (Detail of the Journey of | |

| the Three Kings to Bethlehem) | 138 |

| Cimabue.—Madonna | 144 |

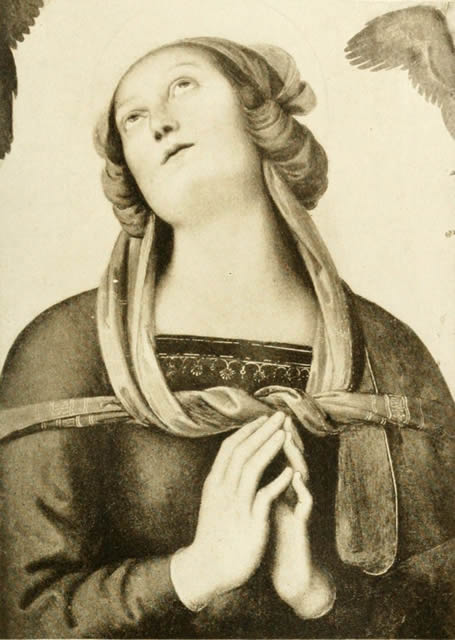

| Perugino.—Assumption of the Virgin (Detail) | 154 |

| Filippo Lippi.—Coronation of the Virgin | 160 |

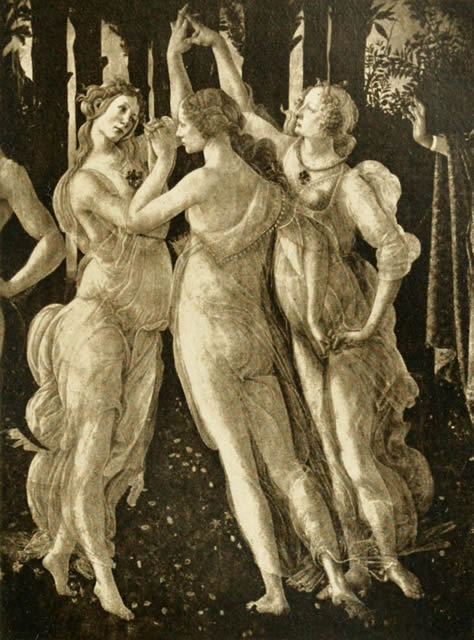

| Botticelli.—Three Graces (Detail of the | |

| Primavera) | 162 |

| Botticelli.—Coronation of the Virgin | 167 |

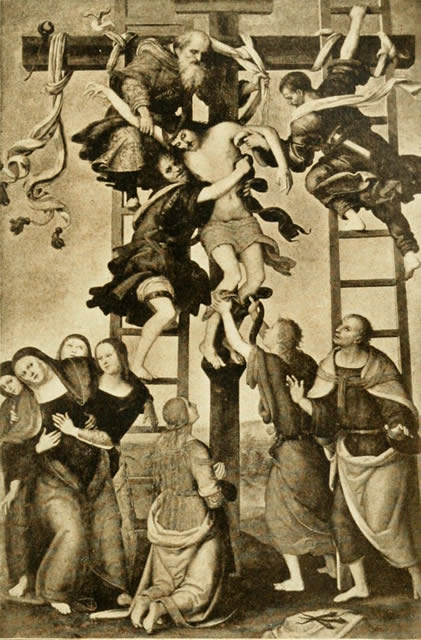

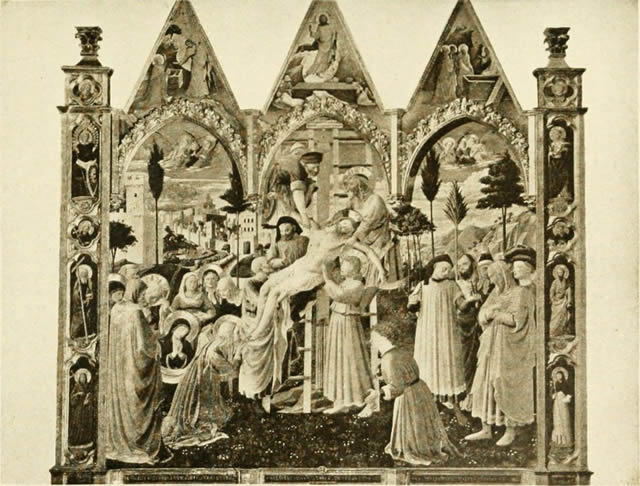

| Filippino Lippi and Perugino.—Descent | |

| from the Cross | 170 |

| Gentile da Fabriano.—Adoration of the | |

| Magi | 176 |

| Fra Angelico.—Descent from the Cross | 178 |

| Giotto.—Adoration of the Magi | 185 |

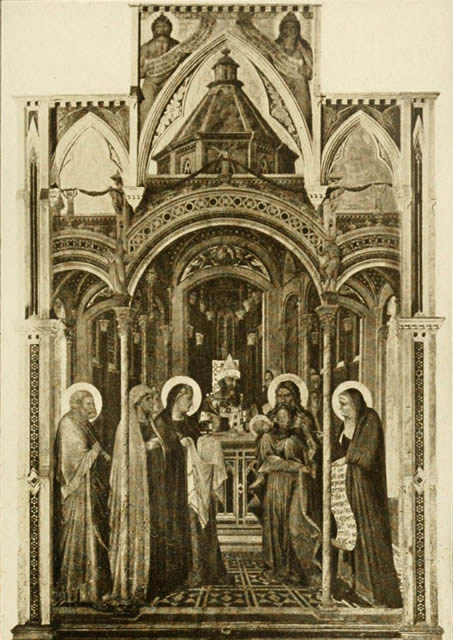

| [xxi]Lorenzetti.—Presentation in the Temple | 188 |

| Carlo Dolci.—Eternal Father | 197 |

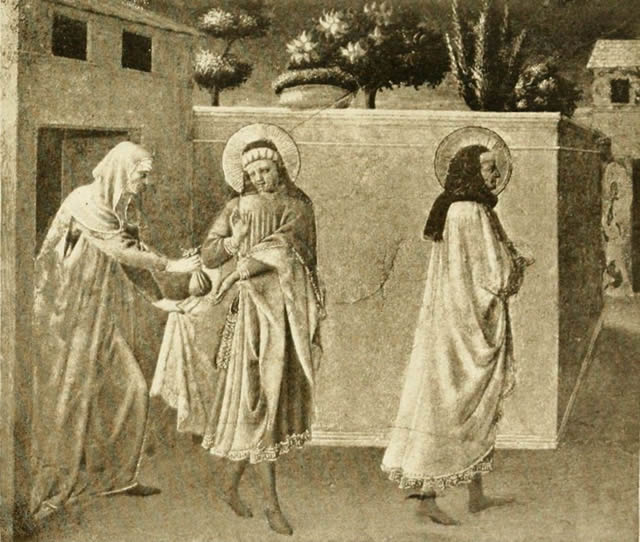

| Fra Angelico.—St. Cosimo and St. Damian | 202 |

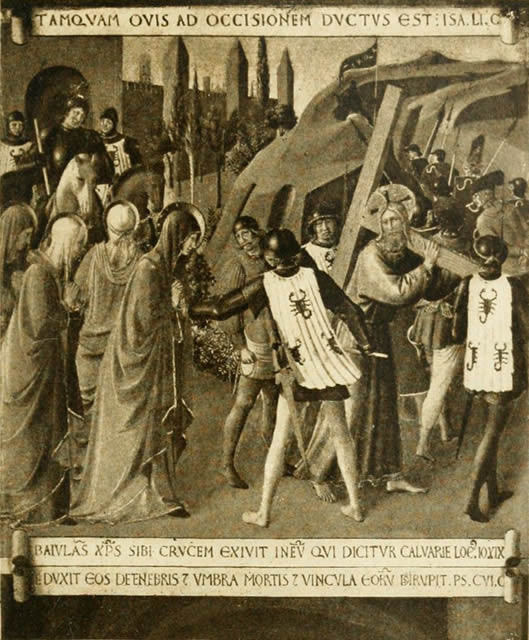

| Fra Angelico.—Way to Calvary | 205 |

| Fra Angelico.—Last Judgment | 208 |

| Filippo Lippi.—Annunciation | 212 |

Only two considerable rivers flow from the Apennines westward into the Mediterranean. The Tiber makes Rome; the Arno makes Florence.

In prehistoric and early historic times, the mountainous region which forms the basin of these two rivers was occupied by a gifted military race, the Etruscans, who possessed a singular assimilative power for Oriental and Hellenic culture. Intellectually and artistically, they were the pick of Italy. Their blood still runs in the veins of the people of Tuscany. Almost every great thing done in the Peninsula, in ancient or modern times, has been done by[2] Etruscan hands or brains. The poets and painters, in particular, with few exceptions, have been, in the wide ethnical sense, Tuscans.

The towns of ancient Etruria were hill-top strongholds. Florence was not one of these; even its neighbour, Fiesole (Faesulae), did not rank among the twelve great cities of the Etruscan league. But with the Roman conquest and the Roman peace, the towns began to descend from their mountain peaks into the river valleys; roads grew important, through internal trade; and bridges over rivers assumed a fresh commercial value. Florence (Florentia), probably founded under Sulla as a Roman municipium, upon a Roman road, guarded the bridge across the Arno, and gradually absorbed the population of Fiesole. Under the later empire, it was the official residence of the “Corrector” of Tuscany and Umbria. During the Middle Ages, it became for all practical purposes the intellectual and artistic capital of Tuscany, inheriting in full the remarkable mental and æsthetic excellences of the Etruscan race.

The valley of the Arno is rich and fertile, bordered by cultivable hills, which produce the[3] famous Chianti wine. It was thus predestined by nature as the seat of the second city on the west slope of Italy. Florence, however, was not always that city. The seaport of Pisa (now silted up and superseded by Leghorn) first rose into importance; possessed a powerful fleet; made foreign conquests; and erected the magnificent group of buildings just outside the town which still form its chief claim upon the attention of tourists. But Florence with its bridge commanded the inland trade, and the road to Rome from Germany. After the destruction of Fiesole in 1125, it grew rapidly in importance; and, Pisa having sustained severe defeats from Genoa, the inland town soon rose to supremacy in the Arno basin. Nominally subject to the Emperor, it became practically an independent republic, much agitated by internal quarrels, but capable of holding its own against neighbouring cities. Its chief buildings are thus an age or two later than those of Pisa; it did not begin to produce splendid churches and palaces, in emulation of those of Pisa and Siena, till about the close of the thirteenth century. To the same period belongs the rise of its literature, under Dante,[4] and its painting under Giotto. This epoch of rapid commercial, military, and artistic development forms the main glory of early Florence.

The fourteenth century is chiefly interesting at Florence as the period of Giottesque art, finding its final crown in Fra Angelico. With the beginning of the fifteenth, we get the dawn of the Renaissance—the age when art set out once more to recover the lost perfection of antique workmanship. In literature, this movement took the form of humanism; in architecture and sculpture, it exhibited itself in the persons of Alberti, Ghiberti, Della Robbia, and Donatello; in painting, it showed itself in Lippi, Botticelli, Ghirlandajo, and Verrocchio. I shall not attempt to set forth here the gradual stages by which these arts advanced to the height at length attained by Leonardo, Michael Angelo, and Raphael; I shall take it for granted that my readers will read up such questions for themselves in Kugler and Layard or other high-class authorities. Nor shall I endeavour to trace the rise of the dynasty of the Medici, whose influence was so great upon the artistic expression of their country; the limits of space which I have imposed upon myself here ren[5]der such treatment impossible. I will rather proceed at once to my detailed examination of the chief existing monuments of Florence in roughly chronological order, leaving these other facts to exhibit themselves piecemeal in their proper place, in connection with the buildings or pictures of the city. For in Florence more than elsewhere I must beg the reader to excuse the needful brevity which the enormous mass of noble works to be explained in this richest of art-cities inevitably entails upon me.

We start, then, with the fact that up to nearly the close of the thirteenth century (1278) Florence was a comparatively small and uninteresting town, without any buildings of importance, save the relatively insignificant Baptistery; without any great cathedral, like Pisa and Siena; without any splendid artistic achievement of any kind. It consisted at that period of a labyrinth of narrow streets, enclosing huddled houses and tall towers of the nobles, like the two to be seen to this day at Bologna. In general aspect, it could not greatly have differed from Albenga or San Gimignano in our own time. But commerce[6] was active; wealth was increasing; and the population was seething with the intellectual and artistic spirit of its Etruscan ancestry. During the lifetime of Dante, the town began to transform itself and to prepare for becoming the glorious Florence of the Renaissance artists. It then set about building two immense and beautiful churches—Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella—while, shortly after, it grew to be ashamed of its tiny San Giovanni (the existing Baptistery), and girded itself up to raise a superb Cathedral, which should cast into the shade both the one long since finished at maritime Pisa, and the one then still rising to completion on the height of Siena.

GENERAL VIEW OF FLORENCE.

Florence at that time extended no further than the area known as Old Florence, extending from the Ponte Vecchio to the Cathedral in one direction, and from the Ponte alla Carraja to the Grazie in the other. Outside the wall lay a belt of fields and gardens, in which one or two monasteries had already sprung up. But Italy at that moment was filled with religious enthusiasm by the advent of the Friars, both great orders of whom, the Franciscans and the Dominicans, had already established[7] themselves in the rising commercial city of Florence. Both orders had acquired sites for monastic buildings in the space outside the walls, and soon began to erect enormous churches. The Dominicans came first, with Santa Maria Novella, the commencement of which dates from 1278; the Franciscans were a little later in the field, with Santa Croce, the first stone not being placed till 1294. Nevertheless, though the Dominican church is thus a few years the earlier of the two, I propose to begin my survey of the town with its Franciscan rival, because the paintings and works of art of Santa Croce are older on the whole than those of Santa Maria, and because the tourist is thus better introduced to the origins and evolution of Florentine art.

Remember, in conclusion, that Florence in Dante’s day was a small town, with little beauty, and no good building save the (since much embellished) Baptistery; but that during Dante’s lifetime the foundations were laid of Santa Maria, Santa Croce, and the great Cathedral. We shall have to trace the subsequent development of the town from these small beginnings.

The Roman name Florentia passed into Fiorenza in mediæval times, and is now Firenze.

From a very early date, St. John the Baptist (to whom the original Cathedral was dedicated) has been the patron saint of Florence. Whenever you meet him in Florentine art, he stands for the city, as St. Mark does for Venice, or the figure of Britannia for our own island.

St. Cosimo and St. Damian, the holy doctors, and therefore patron saints of the Medici family, and especially of Cosimo de’ Medici, also meet us at every turn. They represent the ruling family, and may be recognised by their red robes and caps, and their surgical instruments. Saint Lawrence is also a great Medici saint: in early works, he represents Lorenzo de’ Medici the elder, the brother of Cosimo (1395-1440); in later ones, he stands for Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492). Observe for yourself which of the two the dates in each case show to be intended.

Santa Reparata, the old patroness of the city, and San Zanobi, its sainted bishop, are also frequent objects in early painting and sculpture in Florence.

If you visit the various objects in the order[9] here enumerated, you will get a better idea of the development of Florence and of Florentine art than you could possibly do by haphazard sightseeing. Also, you will find the earlier steps explain the later. But there can be no harm in examining the picture-galleries side by side with the churches, especially if dark or wet days confine you; provided always you begin with the Belle Arti, which contains the A B C of Tuscan and Umbrian panel-painting. From it you can go on to the Uffizi and the Pitti.

St. Francis of Assisi, the Apostle of the Poor, died in 1226, and was promptly canonised in 1228. His followers spread at once over every part of Italy, choosing in each town the poorest quarters, and ministering to the spiritual and temporal needs of the lowest classes. They were representatives of Works, as the Dominicans of Faith. In 1294,—some sixteen years later than the Dominicans at Santa Maria Novella,—they began to erect a church at Florence, outside the walls, on the poorer side of the city, close by their monastery. It was dedicated under the name of Santa Croce, and shortly adorned by Giotto and his pupils with beautiful frescoes, the finest works of art yet seen in Italy. Two things must thus be specially borne in mind about this church: it is a church of the Holy Cross, whose image and[11] history meet one in it at every turn; and it is a Franciscan church, and therefore it is largely occupied with the glorification of St. Francis and of the order he founded. Their coarse brown robes appear in many of the pictures. Look out for their great saints, Bernardino of Siena, Louis of Toulouse, Antony of Padua, etc.

The Franciscans were a body of popular preachers. Hence, in their church, the immense nave, which includes the pulpit, was especially important. It was designed to accommodate large numbers of hearers. But its width and empty spaces also gave free room for many burials; whence Santa Croce became one of the principal churches in Florence for interments. In time, it grew to be the recognised Pantheon or “Westminster Abbey” of the town, where men of literary, scientific, or political importance were laid to rest: and its numerous monuments have thus a sentimental interest for those who care for such memorials. But it would be a great mistake to regard Santa Croce entirely or even mainly from the point of view of a national Walhalla, as is too often done by tourists. Its real interest lies rather in the two points noted above, and in the admi[12]rable works of art with which it is so abundantly supplied, especially in the chapels of the various great families who favoured the order.

The general design is by Arnolfo di Cambio, who at the same time was employed in designing the Cathedral. Begun, 1294; finished, 1442. It is the best museum for the Florentine art of the fourteenth century.

See it by morning light. Choose a bright morning; go past the Cathedral and the Signoria, and then dive down the narrow Borgo de’ Greci, through the tangled streets of the Old Town,—which note as characteristic,—till you arrive at the Piazza Santa Croce. In the centre of the square stands a modern statue of Dante, turning his back on the church which he never really saw. Its walls were only rising a few feet high when the poet was banished from Florence.

CHURCH OF SANTA CROCE AND STATUE OF DANTE.

Proceed first to the north side of the church, to view the exterior of the mediæval building, now much obscured by the later Renaissance loggia. Little of the primitive design is at present visible. Notice the bare brick architecture, intended to be later incased in marble. Observe also the smallness, infrequency, and[13] height from the ground of the windows, and the extreme difference in this respect from the vast stained-glass-containing arches of northern Gothic. Here, the walls themselves support most of the weight, instead of leaving it to buttresses as in France and England. This wealth of wall, however, with the smallness of the windows, permits of the large development of fresco-painting within, which is characteristic of Italian buildings: it also allows room for the numerous monuments. Note at the same time the short transept and small rose window.

Now, go around again to the front. The façade, long left unfinished, was encrusted with marble in 1857, by the munificence of Mr. Sloane, an Englishman, after a Renaissance design, said to be by Cronaca, modified by the modern architect, N. Matas. The nave and aisles have separate gables. Notice, throughout, the frequent occurrence of the Holy Cross, sustained over the main gable by two angels; flanked, on the two lesser gables, by the Alpha and Omega; and reappearing many times elsewhere in the general decoration. The modern reliefs over the doors represent, on the left, the Discovery of the True Cross (Sarrocchi); in[14] the centre, the Adoration of the Cross (Dupré); on the right, the Cross appearing in Heaven to Constantine, and so imposing itself as the symbol of the official religion of the Roman Empire, (Zucchi). Observe the fine Renaissance work of the doorways, with the Alpha and Omega again displayed. High up on the front, over the rose window, is the monogram IHS, introduced by the great Franciscan saint, San Bernardino di Siena. His original example is preserved within. The right side of the church is enclosed by the former buildings of the monastery.

Now, enter the church. The interior is at first sight bare and simple to the degree of positive disappointment. The Franciscans, vowed to poverty, were not a wealthy body. Begin by walking up the centre of the nave, to observe the simple aisles (with no side chapels), the short transepts, the impressive but by no means large Gothic choir (of Arnolfo’s period), and the ten chapels, built out from the transept, as in continuation or doubling of the choir, all of which are characteristic features of this age of Italian Gothic. Each of these chapels was the property of some great mediæval family,[15] such as the Bardi or the Peruzzi. Observe also the plain barn-like wooden roof, so different from the beautiful stone vaulting of northern cathedrals. Architecturally, this very simple interior is severe but interesting.

Now, go down again to the door by which you entered, and proceed along the right aisle, to observe the various objects it contains in detail.

I will dwell upon the monuments very briefly, as mere excrescences upon the original building.

Michael Angelo Buonarotti is buried below on the right; died at Rome, 1564. The general design of the monument is by Vasari; bust by Battista Lorenzi; figure of Architecture by Giovanni dell’Opera; Painting by Lorenzi; Sculpture by Cioli. Pretentious and feeble.

By the pillar on the left, a *Madonna and Child (Madonna del Latte), part of the monument of Francesco Nori, by Antonio Rossellino, fifteenth century, is extremely beautiful.

On the right is Dante’s cenotaph. The poet is buried at Ravenna.

To the left, on a column, stands the famous *pulpit, by Benedetto da Majano, said to be the[16] most beautiful in Italy, though far inferior in effect to that of Niccolò Pisano at Pisa. Its supports are of delicate Renaissance work. The subjects of the reliefs (Franciscan, of course) are, the Confirmation of the Franciscan order, the burning of immoral books, St. Francis receiving the Stigmata, Death of St. Francis, and Martyrdom of Franciscan Saints. Notice the hand holding out the Holy Cross from the pulpit, here more appropriate than elsewhere. The statuettes beneath represent Faith, Hope, Charity, Courage, and Justice.

On the right, opposite it, is the monument of Alfieri, erected for his mistress, the Countess of Albany, by Canova.

Here also are memorials of Macchiavelli, died 1527: monument erected in 1787; and Lanzi, the historian of art.

A fresco, by Andrea del Castagno, with St. John the Baptist, as patron saint of Florence, and St. Francis, as representing the present church and order, alone now remains of all the frescoes of the nave, cleared away by the Goths of the seventeenth century.

INTERIOR OF SANTA CROCE.

Near it is an exquisite **Annunciation by Donatello, of pietra serena, gilt, in a charming[17] Renaissance frame; perhaps the most beautiful object in the whole church. Notice the speaking positions of the angel and Our Lady, the usual book and prie-dieu, and the exquisite shrinking timidity of the Madonna’s attitude. This is worth all the tombs put together.

Over the door is the Meeting of St. Francis and St. Dominic. Compare with the Della Robbia at the Hospital of San Paolo, near Santa Maria Novella.

A beautiful Renaissance tomb of Leonardo Bruni, by Bernardo Rossellino, presents a model afterward much imitated, especially at Venice.

Turn the corner into the right transept. The first chapel on your right, that of the Holy Sacrament, is covered with much-defaced frescoes by Agnolo Gaddi. Recollect that this church is the great place for studying the early Giottesque fresco-painters: first, Giotto; then his pupil, Taddeo Gaddi; next, Taddeo’s pupils, Agnolo Gaddi and Giovanni da Milano. (See Kugler.) On the right wall are represented the lives of St. Nicholas (first bay) and St. John the Baptist (second bay). The most distinct of these frescoes are, first, St. Nicholas appearing in a storm at sea (or, restoring the nobleman[18] his drowned son); and, second, the Baptism of Christ; but some of the others can be faintly recognised, as at the top, the figure of St. Nicholas throwing the three purses of gold as dowries into the window of the poor nobleman with three starving daughters. (See Mrs. Jameson.) The walls here show well the way in which these frescoes were defaced by later additions. On the left wall are frescoed the lives of St. John the Evangelist and St. Anthony, also by Agnolo Gaddi. The scene of the Temptation of St. Anthony is the best preserved of these. Against the pilasters stand life-sized terra-cotta statues of our Franciscan lights, St. Francis and St. Bernardino, by the Della Robbia. On the left wall is the monument of the Countess of Albany.

TADDEO GADDI.—PRESENTATION OF THE VIRGIN.

At the end wall of the right transept is a good Gothic monument of the fourteenth century with reliefs of Christ, the Madonna and St. John, and a Madonna and Child in fresco above, and exquisite little *sculptured angels of the school of Pisa. The chapel of the right transept, known as the Cappella Baroncelli, contains admirable **frescoes from the life of the Virgin, by Taddeo Gaddi. These should[19] all be carefully studied. On the left wall, beginning from above (as always here), in the first tier, Joachim is expelled by the High Priest from the temple, his offering being rejected because he is childless; watching his flocks, he perceives the angel who foretells the birth of the Virgin. Notice the conventional symbolical open temple. (Read the legend later in Mrs. Jameson.) In the second tier, on the left, is the meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate; the servant behind carries, as usual, the rejected offering. On the right is the Birth of the Virgin, the child, as always, being washed in the foreground. Observe closely the conventional arrangement, which will reappear in later pictures. In the third tier, on the left, is the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple by St. Joachim and St. Anna; the young Madonna stands on a single flight of steps (wrongly restored above). Carefully study all the details of this fresco, with its Romanesque or early Gothic architecture and round arches, for comparison with the Giovanni da Milano of the same subject, which we will see later. (At three years old, the Virgin was consecrated to the service of God by Joachim and Anna.) On[20] the right is the Marriage of the Virgin; the High Priest joining her hand to Joseph’s, whose staff has budded, in accordance with the legend. (All were placed in the Holy of Holies, as in the case of Aaron; and he whose staff budded was to wed the Virgin.) Observe the disappointed suitors breaking their staffs, etc. All the incidents are stereotyped. This picture should be carefully noted for comparison both with the Giovanni da Milano here, and with other representations of the Sposalizio elsewhere (e. g. the Raphael at Milan). I strongly advise very long and close study of these frescoes (some of which are imitated directly from Giotto’s in the Madonna dell’Arena at Padua), for comparison both with those originals and with the later imitations by Giovanni da Milano. They cast a flood of light upon the history and evolution of art. Each figure and detail will help you to understand other pictures you will see hereafter. It is a good plan to get photographs of the series, published by Alinari in the Via Tornabuoni, and look at the one series (Gaddi’s), with the photographs of the other (Giovanni’s) in your hands. You cannot over-estimate the importance of such comparison.[21] In the two Presentations, for example, almost every group is reproduced exactly.

On the window wall, above, is an Annunciation on the left; on the right is a Visitation; notice the loggia in the background. These are also most illustrative compositions. In the second tier, on the left, the angel appears to the shepherds; on the right is the Nativity. In the third tier, on the left, the Star appears to the Wise Men; on the right is the Adoration of the Magi. Notice the ages of the Three Kings, representing, as always, the three ages of man, and also the three old continents—Europe, Asia, Africa. Observe the very Giottesque Madonna and Child. This fresco should be compared with the Giotto at Padua.

On the right wall is a fresco by Mainardi: the Madonna ascending in a mandorla, escorted by angels from her tomb, which is filled with roses, drops the Sacred Girdle (Sacra Cintola), now preserved at Prato, to St. Thomas below. (Go to Prato to see it, in order to understand the numerous Sacra Cintola pictures in Florence; and read in Mrs. Jameson, under head, St. Thomas.)

To the left of this chapel is the door leading[22] to the Sacristy. At the end of the corridor is the Cappella Medici, erected by Michelozzo for Cosimo de’ Medici. It contains many beautiful objects. On the right wall is a *marble ciborium, by Mino da Fiesole, with charming angels and an inscription: “This is the living bread which came down from heaven;” also a Giottesque Coronation of the Virgin with four saints—conspicuous among them, Peter and Lawrence. Over the tomb of Lombardi are a beautiful *Madonna and angels of the school of Donatello. On the end wall is our patron, St. Francis with the Stigmata. Over the altar is an exquisite **terra-cotta of the school of Della Robbia, attributed to Luca, a Madonna being crowned by angels, and attended on the left by St. John the Baptist as representing Florence, and on the right by St. Lawrence (for Lorenzo de’ Medici), St. Francis (for this Franciscan church), and St. Louis of Toulouse, the great Franciscan bishop. On the left wall is a famous Coronation of the Virgin, by Giotto, tender in execution, but in his stiffest panel style. It is regarded as a touchstone for his critics. Very graceful faces; crowded composition. Beyond it, notice the Madonna and Child by the Della[23] Robbia, and, over the doorway, a Pietà, by the same, in a frame of fruit. Notice these lovely late fifteenth century majolica objects, frequent in Florence. All the works in this very Franciscan chapel of the Medici, indeed, deserve close inspection. Notice their coat of arms (the pills) over the arch of the altar and elsewhere. It will meet you often in Florence.

Returning along the corridor, to the right, you come to the Sacristy, containing many curious early works, all of which should be noted, such as the Crucifix bowing to San Giovanni Gualberto as he pardons the murderer of his brother, in the predella of an altar-piece by Orcagna, to the left as you enter. The right wall has frescoes of the Passion, by Niccolò di Pietro Gerini, of which the Resurrection, with its sleeping soldiers, mandorla (or almond-shaped glory), and red cross on white banner, is highly typical. Study all these for their conventional features. Notice also the fine roof, and the intarsia-work of the seats and boxes.

A beautiful iron railing of 1371 separates the Sacristy from the Cappella Rinuccini, containing on the left wall, *frescoes of the life of the Madonna by Giovanni da Milano, the close[25] similarity of which to those by his master, Taddeo Gaddi, already observed, should be carefully noticed. The subjects are the same; the treatment is very slightly varied, but pointed arches replace the round ones. At the summit is Joachim expelled from the Temple. In the second tier, on the left, the angel appears to Joachim, and Joachim and Anna meet at the Golden Gate; on the right is the Birth of the Virgin; study the attitudes and note the servant bringing in the roast chicken, St. Anne washing her hands, etc., of all which motives (older by centuries) imitations occur in such later representations of the same scene as Ghirlandajo’s at Santa Maria Novella. In the third tier on the left, is the Presentation in the Temple, with Gothic instead of Romanesque arcade and the steps indicating how those in the Taddeo Gaddi originally ran. (Do not omit to compare these two by means of photographs.) On the right is the Marriage of the Virgin. These two last are specially favourable examples for observing the close way in which Giottesque painters reproduced one another’s motives. I advise you to spend some hours at least in studying and comparing the frescoes of this chapel and the Baroncelli.

On the right wall are scenes from the life of Mary Magdalen, to whom this chapel is dedicated. At the summit she washes the feet of Christ; notice the seven devils escaping from the roof. In the second tier, on the left, is Christ in the house of Mary and Martha; observe Martha’s quaintly speaking attitude; on the right is the Resurrection of Lazarus. In the third tier, on the left, are Christ and the Magdalen in the garden, with the women and angels at the tomb; on the right is a miracle of the Magdalen in Provence (see Mrs. Jameson): she restores to life the wife of a nobleman of Marseilles—a very long story. This fresco is to my mind obviously by another hand: it lacks the simplicity and force of Giovanni. Observe also the fine altar-piece, with the Madonna and Child, flanked by St. John the Baptist and St. Francis, as representing Florence and the Franciscan order; then, St. John the Evangelist, and Mary Magdalen, patroness of the chapel; and, in the predella, scenes from their lives.

Emerge from the Sacristy. Now take the chapels in line with the choir. The first chapel contains faded frescoes, said to be of the age[27] of Cimabue (more likely by a pupil of Giotto), representing the combat of St. Michael and the Devils, which seem to have suggested the admirable Spinello Aretino of the same subject in the National Gallery in London.

The second chapel is uninteresting; the third chapel, of the Bonaparte family, tawdry.

The fourth chapel, the Cappella Peruzzi (called, like the others, after the family of the owners), contains the famous frescoes by Giotto, from the lives of the two St. Johns. On the left wall is the life of St. John the Baptist, the patron of Florence. In the upper tier, the angel appears to Zacharias. In the second tier, on the right, is the Birth of the Baptist; on the left he is presented to Zacharias, who writes down “His name is John.” In the third tier, Herodias’s daughter receives his head, and presents it to her mother. The attitude of the player, and the arrangement of the king’s table reappear in many later compositions. Look out for them hereafter. On the right wall is the life of St. John the Evangelist. At the summit he has the vision of the Apocalypse in a quaintly symbolical isle of Patmos. In the second tier he raises Drusiana, an admirable[28] opportunity for the study of Giotto’s style of drapery. The St. John in this fresco already contains premonitions of Masaccio and even of Raphael. In the third tier, he is taken up into heaven by Christ in clouds, accompanied by the Patriarchs: a magnificent dramatic composition. These frescoes, which represent the maturest work of Giotto’s manhood, should be closely studied in every detail. Spend many hours over them. Though far less attractive than his naïve earlier work in the Madonna dell’Arena at Padua, they yet display greater mastery of drawing and freedom of movement. Do not let one visit suffice for them. Compare them again and again with photographs from the Arena, and look out for imitations by later painters. Do not overlook the altar-piece, by Andrea del Sarto. It represents the two great plague-saints—San Rocco and St. Sebastian. The Franciscans were great nursers of the plague-stricken, and this altar was one where vows were offered for recovery.

GIOTTO.—RAISING OF DRUSIANA.

The fifth chapel, the Cappella Bardi, contains other frescoes, also by Giotto (unfortunately over-restored), of the life of St. Francis. These were once the chief ornament of this[29] Franciscan church. On the left wall, at the summit, he divests himself of his clothing and worldly goods, and leaves his father’s house, to be the spouse of Poverty. In the second tier he appears suddenly at Arles, to Sant’Antonio of Padua, while preaching. (Read up all these subjects in Mrs. Jameson’s Monastic Orders.) In the third is the Death of St. Francis; his soul is seen conveyed by angels to heaven. This picture, which formed the model for many subsequently saintly obsequies, should be compared at once with the Ghirlandajo of the same theme in the Santa Trinità in Florence. On the right, at the summit, St. Francis receives the confirmation of the rules of his order from Pope Innocent III. In the second tier is his trial of faith before the Sultan. In the third tier are his miracles (appearance to Guido d’Assisi: a dying brother sees his soul leaping toward heaven). Consult parts I. and III. of Ruskin’s “Mornings in Florence,” on the subject of these frescoes, but do not be led away by his too positive manner. On the ceiling are St. Francis in Glory, and his three great virtues, Poverty, Chastity, Obedience. Note also the figures of the chief Franciscan luminaries, St.[30] Louis of Toulouse, St. Louis of France, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, and St. Clara (foundress of the Franciscan female order of Poor Clares), round the windows. The whole is thus an epic of Franciscanism. Study it fully. The curious ancient altar-piece of this chapel deserves attention.

On the archway, above this chapel, outside, is St. Francis receiving the Stigmata, by Giotto—resembling the altar-piece of the same subject in the Louvre, painted by Giotto for San Francesco at Pisa. I recommend long observation of all these Giottos. Go later to Assisi, the town of St. Francis, and compare them with the Giottos in the parent monastery. The choir, which is, of course, the central point of the whole church, usually bears reference to the name and dedication: here, it is naturally adorned by the History of the Holy Cross, depicted in fresco on its walls by Agnolo Gaddi. These frescoes, however, are so ill seen, owing to the railing, and the obstacles placed in the way of entering, that I will merely give a brief outline of their wild legend as here represented.

On the right wall, in the first fresco, Seth[31] receives from an angel a branch from the Tree of Knowledge. He is told to plant it in Adam’s heart, with an admonition that when it bears fruit, Adam will be restored to life again.

In the second fresco, the Tree, cut down by Solomon for use in the Temple, and found unsuitable, is seen in passing by the Queen of Sheba, who beholds a vision of the crucified Saviour, and falls down to worship it.

In the third, the Tree is found floating in the Pool of Bethesda, and is taken out to be used as the Cross of the Saviour.

In the fourth, the Holy Cross, buried for three hundred years, is discovered by the Empress Helena, who distinguishes it by its powers in healing sickness.

On the left wall, in the fifth fresco, Helena carries the Holy Cross in procession amid public rejoicing.

In the sixth, Chosroes, King of Persia, takes Jerusalem, and carries off a part of the Holy Cross which was still preserved there.

In the seventh, Heraclius, Emperor of the East, conquers and beheads Chosroes, and rescues the Holy Cross from the heathen.

In the eighth, Heraclius brings the Holy[32] Cross in triumph to Jerusalem, and carries it barefoot on his shoulders into the city.

In the first chapel, beyond the choir, is an interesting altar-piece.

The second and third chapels contain nothing noteworthy.

The fourth chapel, of St. Stephen and St. Lawrence, contains frescoes by Bernardo Daddi, an early Giottesque. On the left are the Trial and Martyrdom of St. Stephen, on the right the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence, with the usual boy blowing the bellows. The scene is caught at the famous moment when the Saint is saying, “Turn me over; this side is done.” (Jam versa: assatus est.) To the left and right of the windows are St. Stephen and St. Lawrence, with their palms of martyrdom. (These two deacon saints are usually painted in couples. They similarly share Fra Angelico’s chapel in the Vatican.) Over the altar is a somewhat vulgarly coloured relief of the Madonna and Child, with angels; St. John the Evangelist, holding his symbol, the cup and serpent, and St. Mary Magdalen, with the alabaster box of ointment. Notice the Annunciation and the little saints in the predella of this work. Their order from[33] left to right is: St. Dominic with his star; St. Lucy with her eyes in a dish; St. Catherine of Alexandria with her wheel; and St. Thomas Aquinas with his open book. A Dominican work in this Franciscan church, placed here, no doubt, by some Dominican-minded donor.

The fifth chapel, of St. Sylvester, contains frescoes by Giottino or Maso di Banco. On the left, over the tomb of Uberto de’ Bardi, is the Last Judgment, with the dead man rising solitary. Over the next tomb,—this is more probably by Taddeo Gaddi,—the Entombment, all the attitudes in which are characteristically Giottesque, and should be carefully noted. On the right wall is the Conversion of Constantine, and the miracles of St. Sylvester, greatly faded (exorcism of a dragon, etc.). Notice, in the lower tier, two dead men restored to life, naïvely represented in the usual fashion, the dead bodies below, the living rising out of them. Similar scenes will meet you elsewhere.

The end chapel of the left transept contains no work of importance. Observe from its steps the general view of the building.

In the chapel beyond transept are modern monuments and paintings.

Return by the left aisle, passing a monument of Raphael Morghen, and a **monument of Carlo Marsuppini, by Desiderio da Settignano, an exquisite specimen of Renaissance work, with lovely decorative framework, and charming boy-angels holding the coat of arms of the deceased. Every portion of the decoration of this exquisite tomb should be examined in detail. Observe in particular the robe and tassels. It is a masterpiece of its period.

Many of the late altar-pieces in this aisle are worth passing attention as specimens of the later baroque painting.

Notice also the tomb of Galileo Galilei, died 1642, and, over the holy water stoup, St. Francis with the Stigmata.

TOMB OF GALILEO GALILEI.

On the entrance wall of the nave, in the rose window, is a Descent from the Cross, thus completing the series of the Holy Cross, from a design by Ghiberti; beneath it, the original IHS, from the design of St. Bernardino of Siena, the holy Franciscan, who placed it with his own hands on the old façade. Over the central door stands a statue of St. Louis of Toulouse, the other great Franciscan saint, by Donatello; beneath his feet, the crown which he[35] refused in order to accept the monastic profession. Study well all these Franciscan memorials, and observe their frequent allusiveness to the Holy Cross.

The reader must not suppose that in this brief enumeration I have done anything more than hastily touch upon a point of view for the chief objects of interest in this most important church. He must come here over and over again, and study the various chapels and their frescoes in order. I have passed over endless minor works whose meaning and interest will become more and more apparent on further examination. Regard Santa Croce as a museum of the early Giottesque fresco-painters, and recollect that only in Florence, with Assisi and Padua, can you adequately study these great artists. If the study attracts you, read up in Layard’s Kugler the portion relating to Giotto, Taddeo Gaddi, and Giovanni da Milano; and also in Mrs. Jameson the legends of the chief saints here commemorated. Then return to correct and enlarge your first impressions. Afterward go on to Assisi and Padua. It is impossible to estimate the Giottesques outside Italy.

Through the cloisters of the Franciscan monastery, to the right, outside the church (designed by Arnolfo), you gain access to the Cappella de’ Pazzi, founded by the great family whose name it bears, the chief rivals of the Medici. It is a splendid work by Brunelleschi, the architect of the dome of the Cathedral. The beautiful frieze of angels’ heads without is by Donatello and Desiderio de Settignano. You can thus study here these two early Renaissance sculptors. Within are terra-cotta decorations by Luca della Robbia: the twelve Apostles and the four Evangelists. The shape of the roof is characteristic.

To the right of the cloisters on entering is the old refectory of the convent, on the end wall of which, as on most refectories, is painted in fresco the Last Supper, attributed to Giotto, more probably by Taddeo Gaddi. This Cenacolo should be carefully studied as the one from which most later representations are gradually derived. Notice the position of Judas in the foreground, long maintained in subsequent paintings. I advise you to get photographs of this work for comparison with the Ghirlandajo at San Marco, the Cenacolo di Fuligno, etc. The[37] Crucifixion, above, has near it a Genealogical Tree of the Franciscan order; close by, St. Francis receiving the Stigmata, History of St. Louis of Toulouse, and the Magdalen at the feet of Christ in the house of the Pharisee. All these, again, should be noted for comparison; they are probably the work of a pupil of Taddeo’s. Do not omit to observe the Franciscan character here, too, nor the frequency of the outcast figure of the Magdalen. The Franciscans—the Salvation Army of their day—ministered especially to the poor and sinful.

St. Dominic of Castile, the great contemporary and friendly rival of St. Francis, died in 1221. The order which he founded (distinguishable in art as in life by its black and white robes) soon spread over Italy. The Dominicans constituted themselves the guardians of Faith, as the Franciscans were the apostles of Works; they protected the faithful against heresy, and extirpated heretics. The Holy Inquisition grew out of their body. They were also, incidentally, the leading teachers of scholastic philosophy; they posed as the learned order. As preachers, they chiefly expounded the doctrines of the Church, and preserved its purity.

STROZZI PALACE.

The Dominicans were the earliest builders of any important monumental church at Florence.[39] In 1278 (some sixteen years before the Franciscans at Santa Croce), they began to erect a splendid edifice on the west side of the town, in the garden belt outside the narrow walls of the earliest precinct. It served as chapel to their monastery. The design for this church, in pure Tuscan Gothic, was prepared by two Dominican monks, Fra Sisto and Fra Ristoro; and the building was finished (except the façade) about 1355. The façade itself is a later Renaissance addition to the original building.

Before examining Santa Maria Novella, however, I strongly advise the visitor to begin by inspecting the Strozzi Palace, in the Via Tornabuoni. This massive Tuscan residence forms a typical example of the solid and gloomy Florentine palaces—half fortress, half mansion. It was built, as a whole, in 1489 (long after Santa Maria), by Benedetto da Majano, for his patron, Filippo Strozzi, the chief rival of the Medici in the later fifteenth century. The beautiful cornice which tops its exterior on the side next the Via Strozzi was added later by Cronaca. But it is well to inspect (from without) this magnificent house before visiting Santa Maria, because both Filippo Strozzi and Benedetto da[40] Majano will meet us again more than once in the church we are about to consider. Observe that the solid Tuscan palaces of which this is the type are designed like fortresses, for defence against civic foes, with barricaded windows high up on the ground floor, and a castle-like front; while they are only accessible by a huge gate (readily closed) into a central courtyard, lighter and airier, on which the principal living-apartments open. (These palaces incidentally give you the clue to the Cour du Louvre.) Note the immense blocks of stone of which the wall is composed, and the way they are worked; observe also the windows, doorways, corner-lanterns, and rings or link-holders of the exterior; then walk into the court, whose front was added somewhat later by Cronaca. Contrast these fortress town-houses of the turbulent Florentine nobles with the relatively free and open mansions of the mercantile Venetians, among whom (under the strong rule of the Doges and the oligarchy) internal peace was so much earlier secured. Remember finally that the Strozzi were among the chief patrons of Santa Maria Novella.

From the Strozzi Palace, again, walk just[41] around the corner into the Via della Vigna Nuova, and inspect the exterior of the slightly earlier Rucellai Palace. The family who built it were the pillars of Santa Maria and of the Dominican order. It was designed by Leon Battista Alberti, the first of the famous Renaissance architects; it is remarkable for the pilasters which here first intervene between the so-called rustica work of the masonry. These two palaces give you a good idea of the Tuscan houses. If you wish to learn more of Alberti’s style inspect also the dainty little (blocked-up) arcade or loggia opposite; as also the Rucellai Chapel in the Via della Spada, which encloses an imitation by Alberti of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem. And now you are in a position to understand Santa Maria, the façade of which this same Alberti designed.

Recollect then, in the first place, that it is a Dominican church, full of the glory of the Dominicans, and of their teaching function, as well as of their great philosophic saints, in particular, St. Thomas Aquinas—look out for their black-and-white robes; and, in the second place, that it is the church of the Rucellai, the Strozzi, the Tornabuoni, and other wealthy and noble[42] Florentine families. Earlier in date than Santa Croce as to its fabric, I place it later in the order of our tour, because its contained works of art are of later date, and its style less uniform.

Choose a very sunny day; go into the Piazza Santa Maria Novella. Observe the church, and the opposite hospital of San Paolo; there is a good relief of the Meeting of St. Dominic and St. Francis, by the Della Robbia, in the right corner of the latter, under the loggia. Then, walk around the right corner of the church into the Piazza dell’Unità Italiana, where stand by the obelisk to examine the exterior of the mediæval portion of the building, with its almost windowless nave and aisles, and its transept with small rose window. This part was designed for the Rucellai by two Dominican monks about 1278. Afterward, proceed toward the railway station, so as to observe the architecture of the end of the church, and the interesting campanile. This is all part of the primitive building.

Now, return to the much later Renaissance façade, erected by Leon Battista Alberti in 1456 for Giovanni Rucellai. This façade is well worth[43] close notice, as a specimen of early Renaissance architecture. Observe first the earlier Gothic arcades (avelli), in black and white marble, which surround the corner. These were used as burial vaults, and contain, below, the coats-of-arms of the various noble families interred there. Those to the right have been over-restored; but on the lower tier of the façade itself, and to the left by the monastery buildings, they still remain in their original condition. The two lateral doorways are also early and Gothic. The central doorway, however, and the rest of the façade, in black and white marble, and serpentine,—at least, the part above the first cornice,—belongs to the later Renaissance design added by Alberti. If you go around to the front of the neighbouring church of San Lorenzo, you will see the way in which such façades were often left incomplete for ages in Italy. Notice the contrast between the later and earlier portions; also the handsome green pilasters. At Santa Croce, the nave and aisles have separate gables; here, only the nave has a visible gable-end, while the apparently flat top of the aisles is connected with it by a curl or volute, which does not answer to the interior[44] architecture. Beneath the pediment runs the inscription: “Iohannes Oricellarivs, Pav[li] Fil[ivs] An[no] Sal[vationis] Mcccclxx”; that is to say, “Giovanni Rucellai, son of Paolo, in the Year of Salvation, 1470.” Look out within for more than one memorial of these same Rucellai, the great joint patrons of Santa Maria Novella.

Enter the church. The interior, a fine specimen of Tuscan Gothic, consists of a nave and aisles, with vaulted roof (about 1350), and a transept somewhat longer than is usual in Italian churches.

Walk up the centre of the nave to the junction of the transepts (mind the two steps half way) in order to observe the internal architecture in general, and the position of the choir and chapels, much resembling that of Santa Croce: only, the transepts end here in raised chapels.

INTERIOR OF SANTA MARIA NOVELLA.

Then, return to the right aisle, noticing, on the entrance wall, to the right of the main door, a beautiful little Annunciation of the fifteenth century, where the position of the Madonna and angel, the dividing wall, prie-dieu, bed in the background, etc., are all highly character[45]istic of this interesting subject. Beneath it, three little episodes, a Baptism, an Adoration of the Magi, and a Nativity, closely imitated after Giotto. To the left of the doorway is a Holy Trinity, with saints and donors, much injured, but still a fine work by Masaccio. The altar-pieces in the right aisle are of the seventeenth century, and mostly uninteresting. One is dedicated to St. Thomas à Becket.

In the right transept is a bust of St. Antoninus, the Dominican Bishop of Florence. (The Dominicans make the most of their saints here, as the Franciscans did at Santa Croce.)

Beyond the doorway is the Tomb of Joseph, Patriarch of Constantinople, who came to the Council of Ferrara (afterward at Florence) in order to arrange a basis of reunion for the Eastern and Western Churches, and then died here, 1440. (The beautiful fresco of the Journey of the Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli at the Riccardi Palace, which you will visit later, contains his portrait as the Eldest King.)

Above this is the early Gothic Tomb of Aldobrandino (1279), with Madonna and Child, added, by Nino Pisano. To the right is another tomb (Bishop Aliotti of Fiesole, died 1336)[46] with recumbent figure, Ecce Homo, etc., best viewed from the steps to the end chapel: this is probably by Tino da Camaino. Note these as specimens of early Tuscan sculpture.

Ascend the steps to the Rucellai Chapel. (Remember the family.) Over the altar is Cimabue’s famous Madonna, with attendant angels superimposed on one another. This celebrated picture, the first which diverged from the Byzantine (or rather barbaric Italian) style, is best seen in a very bright light. It forms the starting-point for the art of Tuscany. A replica, with slight variations, can be studied with greater ease in the Belle Arti. This famous work is the one which is said to have been borne in triumph from the painters studio to the church by the whole population. Note the greater freedom in the treatment of the angels, where Cimabue was less bound by rigid custom than in Our Lady and the Divine Child. On the right wall is a characteristic Giottesque Annunciation, where the loggia and the position of the angel should be noted; on the left wall is St. Lucy, with her eyes in a dish, by Ridolfo Ghirlandajo. The tomb of the Beata Villana (with angels, as often, drawing the cur[47]tains) is by Bernardo Rossellino. The Martyrdom of St. Catherine is by Bugiardini. Come again to this chapel to study the Cimabue after you have seen the copy in the Belle Arti.

Notice outside the chapel, as you descend the stairs, the Rucellai inscriptions, including the Tomb of Paolo, father of Giovanni, who erected the façade.

Now, turn to the Choir Chapels, extending in a line to the left as you descend. And observe here that, just as the exterior belongs to two distinct ages, Mediæval and Renaissance, so also do the frescoes. The Orcagnas and the paintings of the Spanish Chapel are Giottesque and Mediæval; the Filippino Lippis and the Ghirlandajos are Renaissance. We come first upon the later series.

FILIPPINO LIPPI.—RAISING OF DRUSIANA.

The first chapel is uninteresting.

The second chapel, of the Strozzi family, the other great patrons of Santa Maria Novella, was formerly, as the Latin inscriptions relate, dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, but was afterward made over by Filippo Strozzi (builder of the Strozzi Palace) to his family patrons, St. Philip and St. James. The same powerful nobleman employed Filippino Lippi to deco[48]rate it with **frescoes, which rank among the finest work of that great Renaissance master. Here you come for the first time upon a famous Florentine painter of the fifteenth century. Contrast his frescoes with the Giottesque types at Santa Croce, and observe the advance they mark in skill and knowledge. The left wall contains scenes from the life of the (dispossessed) St. John the Evangelist, as compensation for disturbance. Below, St. John raises Drusiana, a legendary subject which we saw at Santa Croce. Observe here, however, the Roman architecture, the attempts at classical restoration, and the admirable dramatic character of the scene, especially visible in the strange look of wonder on the face of the resuscitated woman herself, and the action of the two bier-bearers. The group of women, mourners, and children to the right should be carefully studied as typical of Filippino Lippi’s handiwork (about 1502). Above is St. John in the caldron of boiling oil. Observe again the classical tone in the lictors with fasces and other Roman insignia. The right wall is devoted to the legendary history of St. Philip, the namesake of both patron and[49] painter. Below, St. Philip exorcises a dragon which haunted a temple at Hierapolis in Phrygia, and killed by its breath the king’s son. Here again the dramatic action is very marked, both in the statue of Mars, the priest, the mourning worshippers, and the dragon to the left, and the dying prince in the arms of his courtiers to the right of the picture. Above is the Martyrdom of St. Philip, who is crucified by the outraged priests of the dragon. These frescoes, though marred by restoration, deserve attentive study. Their exaggerated decorative work is full of feeling for the antique. They are characteristic but florid examples of the Renaissance spirit before the age of Raphael. (Good accounts in Layard’s Kugler, and Mrs. Jameson.) Note, however, that while excellent as art they are wholly devoid of spiritual meaning—mere pleasant stories. On the window wall is the tomb of Filippo Strozzi by Benedetto da Majano, the architect of the Strozzi palace. (Notice throughout this constant connection of certain painters and sculptors with families of particular patrons, and also with churches of special orders.) The Madonna and Child, flying angels, and framework, are all exquisite[50] examples of their artist’s fine feeling. The bust of Filippo Strozzi, from this tomb, is now in the Louvre. The window above, with Our Lady, and St. Philip and St. James, is also after a design by Filippino Lippi. Observe likewise the admirable Sibyls and other allegorical figures of the window wall. Not a detail of this fine Renaissance work should be left unnoticed. Do not forget the Patriarchs on the ceiling, each named on a cartolino or little slip of paper. Return more than once to a chapel like this, reading up the subjects and painters meanwhile, till you feel you understand it.

Enter the choir, noticing, as you pass, the marble high altar, which covers the remains of the Dominican founder, the Beato Giovanni di Salerno.

The **frescoes on the walls were originally by Orcagna, but in 1490 Giovanni Tornabuoni commissioned Domenico Ghirlandajo to paint them over with the two existing series, representing, on the right wall, the life of St. John the Baptist, the patron saint of the city, and, on the left wall, the history of the Virgin, the patron saint of Santa Maria Novella. (Here,[51] therefore, as usual, the Choir contains direct reference to the dedication.)

The upper scenes on either side are so much damaged as to be hardly recognisable, but the lower ones are as follows:

On the left wall, in the second tier to the left, is the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, which should be compared with similar scenes by earlier Giottesque painters, in Santa Croce; on the right, the Marriage of the Virgin; observe again the positions of Joseph, Mary, the High Priest, the attendant Virgins of the Lord, and the disappointed suitors, breaking their staffs, etc. (Recall or compare with photograph of Raphael’s Sposalizio at Milan.) In the lowest tier, on the left, is the Expulsion of Joachim from the Temple (because he is childless) where the spectators (introduced as if viewing the facts) are contemporary Florentine portraits of the painter and his brother, and the family and friends of the Tornabuoni. Contrast the details with the Giottesques at Santa Croce: noble figures of the High Priest and St. Joachim. On the right is the Birth of the Virgin, with St. Anne in bed, the washing of the infant, and a group of Florentine ladies[52] as spectators: conspicuous among them, Lodovica, daughter of Giovanni Tornabuoni; in the background, the Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate. In all these pictures, the survivals and modifications of traditional scenes should both be noted; also, the character of the architecture and the decorative detail in which Ghirlandajo delighted. He had been trained as a goldsmith, and retained through life his love of goldsmith-like handicraft. The introduction of portraits of contemporaries as spectators is highly characteristic both of age and artist. Ghirlandajo was in essence a portrait-painter, who used sacred scenes as an excuse for portraiture.

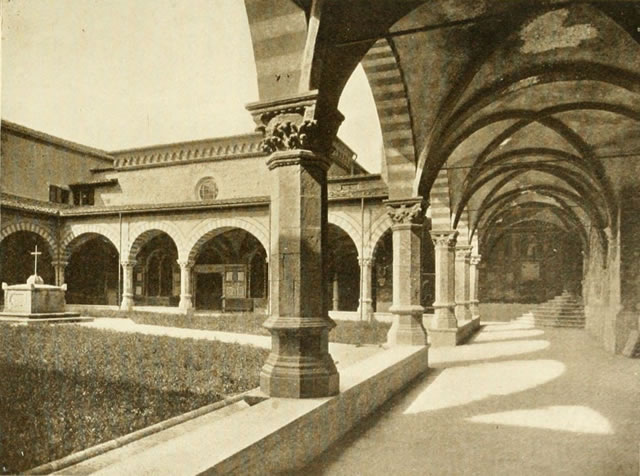

GHIRLANDAJO.—BIRTH OF JOHN THE BAPTIST (DETAIL).

On the right wall, in the lower tier, to the left, is the Visitation, where the positions of the Madonna and St. Elizabeth should be noted, as those on which later pictures by Mariotto Albertinelli, Pacchiarotto, etc., are based, and also as derived from earlier examples. Here, also, notice the contemporary portraits. The lady, standing very erect, in a stiff yellow gown, is Giovanni Tornabuoni’s stepdaughter, Giovanna Albizi, the same person of whom a portrait by Ghirlandajo (a study for this picture)[53] exists in the National Gallery in London, and who is also introduced in the two frescoes by Botticelli at the head of the principal stairs in the Louvre. On the right is the Angel appearing to Zacharias, where a group of contemporary portraits of distinguished Florentines is particularly celebrated; Baedeker names them; I will not, as you will have his book with you. In the second tier, on the left, Zacharias writes “His name is John.” On the right is the birth of the Baptist. Sit on the seats a long time, and study au fond these typical and important frescoes.

On the window wall are ill seen and defaced frescoes, also by Ghirlandajo, of St. Francis before the Sultan, and St. Peter Martyr killed by assassins; the Annunciation, and St. John the Baptist in the desert; and, below all, Giovanni Tornabuoni and his wife, the donors of these frescoes. Observe here in the choir, which is, as it were, the focus of the church, that almost everything refers to the Blessed Virgin, the patroness of this building, or to St. John the Baptist, the patron of the town in which it is situated.

I cannot too strongly recommend close study[54] of these late Renaissance pictures of the age immediately preceding that of Raphael. Do not be satisfied with noting the few points I mention: look over them carefully as specimens of an epoch. Specially characteristic, for example, is the figure of the nude beggar in the scene of the Presentation of the Virgin, on the left wall, showing the growing Renaissance love for nude anatomy. On the other hand you will find in the same picture the positions of St. Jerome and St. Anna, of the two children, and of the two men in the foreground, as well as that of the Madonna pausing half-way up the steps, exactly equivalent to those in the Taddeo Gaddi and the Giovanni da Milano. Photographs of all these should be compared with one another, and also with the famous Titian at Venice. I have tried to give some hints on this subject in an article on the Presentation in the Temple contributed to the Pall Mall Magazine in 1895.

The first chapel beyond the choir is uninteresting. It contains, however, a famous crucifix by Brunelleschi, which would seem to show that a crucifix, by whomsoever designed, is still a crucifix.

The second chapel, of the Gaddi, contains good bas-reliefs by Bandini.

Under the steps which lead to the elevated Strozzi Chapel (the second belonging to the family in this church) is a tomb with Gothic figures and a Giottesque Entombment, attributed to Giottino.

Ascend the steps to the Strozzi Chapel, the altar of which covers the remains of a “Blessed” member of the family, the Beato Alessio dei Strozzi. This chapel contains some famous Giottesque frescoes by the brothers Orcagna.

On the window wall is the Last Judgment, by Andrea Orcagna, with Angels of the Last Trump, the twelve apostles, the rising dead, and other conventional elements. Conspicuous just below the figure of the Saviour are, to the left, Our Lady, patroness of this church, and to the right St. John the Baptist, patron of this city. On the right of the Saviour are the elect; to the left of him, the damned. Every one of the figures of the rising dead, saints, and apostles, with the angels bearing the instruments of the Passion, deserve close attention. Most of them will recur in many later pictures. Com[56]pare the similar scene in the Campo Santo at Pisa.

On the left wall is the Paradise, also by Andrea, a famous and most beautiful picture, with Christ and the Madonna enthroned, and an immense company of adoring saints and angels. As many as possible of these should be identified by their symbols. Return from time to time and add to your identifications. The tiers represent successively Seraphim and Cherubim, Apostles, Prophets, Patriarchs, Doctors of the Church, Martyrs, Virgins, Saints, and Angels. Notice the suitability of this dogmatic arrangement in a Dominican church, belonging to the stewards and guardians of orthodoxy. The painting unites Florentine grandeur with Sienese tenderness.

On the right wall is a very ugly Inferno, attributed to Orcagna’s brother, Bernardo, and divided into set divisions, in accordance with the orthodox mediæval conception, which is similarly crystallised in Dante’s poem. The various spheres are easily followed by students of the “Divina Commedia.”

Do not omit to observe the very beautiful altar-piece, also by Orcagna. Its chief subject[57] is Christ giving the keys, on the one hand, to Peter, and the book, on the other hand, to the great Dominican saint and philosophical teacher, St. Thomas Aquinas. The allegorical meaning is further accentuated by the presence of the Madonna and St. John, patrons of this church and city. We have thus St. Thomas placed almost on a plane of equality with the Papacy. The other figures are St. Michael the Archangel, St. Catherine with her wheel, St. Lawrence with his gridiron, and St. Paul with his sword. In the predella beneath are subjects taken from the stories of the same saints. The most interesting is the struggle for the soul of the Emperor Henry II. (See Mrs. Jameson.) The Emperor is seen dying; then, devils go to seize his soul; a hermit sees them; St. Michael holds the scales to weigh the souls; the devils nearly win, when, suddenly, St. Lawrence descends, and places in the scale a gold casket which the Emperor had presented to him (once at Bâle, now in the goldsmiths’ room at the Musée de Cluny); the scale bends down, and the devils in a rage try to seize St. Lawrence. A quaint story, with an obvious moral, well told in this predella with spirit and vigour.

This chapel as a whole is one of the best smaller examples now remaining of a completely decorated Giottesque interior. Not a single element of its frescoes and Dominican symbolism should pass without notice. Observe, before you leave, St. Thomas Aquinas on the arch, in four characters, as Prudence, Justice, Courage, and Temperance. The Strozzi Chapel again is one to which you must pay frequent visits.

Descend the steps. The door in front leads to the Sacristy. The most interesting object in it is a lavatory in marble and terra-cotta of the school of Della Robbia. The pictures of Dominican saints with which it is adorned have little more than symbolical interest.

The left aisle contains no object of special interest.

This completes a first circuit of the church itself; but you have still to see the most interesting object within its walls—the Spanish Chapel. Do not attempt, however, to do it all in one day. Return a second bright morning, between ten and twelve, and pay a visit to this gem of early architecture and painting.

A door to the right of the raised Strozzi chapel, in the left transept, leads into the cloisters. It is locked. You must get the sacristan to open it. He is usually to be found in the Sacristy.

The first cloister which you enter, known as the Sepolcreto, and containing numerous mediæval or modern tombs, has faded Giottesque frescoes, two of which, in the bay to the right as you descend the steps, pretty enough in their[60] way, have been made famous (somewhat beyond their merits) by Mr. Ruskin. That on the left, in a curiously shaped lunette, represents, with charming naïveté, the Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate. Observe the conventional types of face and dress in the two saints, and the angel putting the heads of the husband and wife together; also, the servant carrying the rejected offering, all of which are stereotyped elements in the delineation of this subject. The fresco to the right represents the Birth of the Virgin, and may be instructively compared with the Ghirlandajo up-stairs, and also with the Taddeo Gaddi and the Giovanni da Milano at Santa Croce. The simplicity of the treatment is indeed reminiscent of Giotto’s manner, but few critics, I fancy, will agree with Mr. Ruskin in attributing these works to the actual hand of the master. Remember, too, that Giotto is always simple, because he is early; later times continually elaborated and enriched his motives. On the side walls, to the left, the angel appears to Joachim and Anna simultaneously; on the right is the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple. Compare these naïve works with the frescoes in[61] the Madonna dell’Arena at Padua, and other examples.

GREEN CLOISTER IN SANTA MARIA NOUVELLA.

This cloister also contains a vulgarly coloured and somewhat coarse terra-cotta relief of Christ as the Gardener and the Magdalen in the Garden. I will not further particularise, but several hours may be spent in examining the objects in this single courtyard alone, many of which are extremely interesting. From the base of the oratory containing this relief is also obtained one of the best views of the church and campanile.

The second cloister, known as the Chiostro Verde, is decorated with very faded frescoes, in shades of green, representing the history of Genesis. There is a good general view of the church and campanile from the farther end of this cloister.