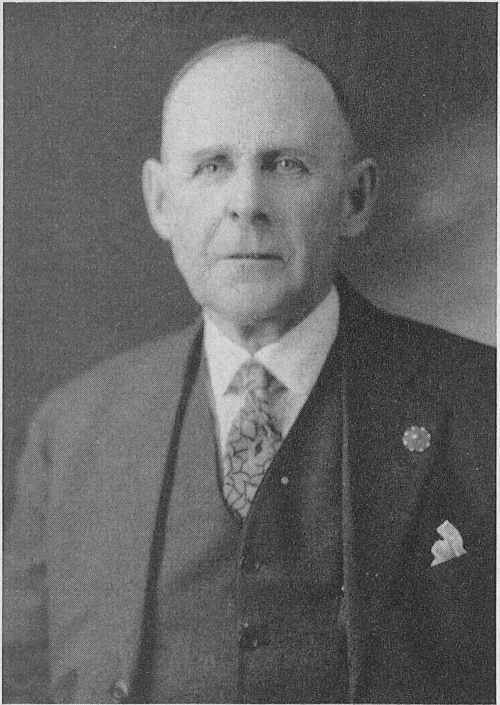

WM. BLEASDELL CAMERON

* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Blood Red the Sun

Date of first publication: 1926

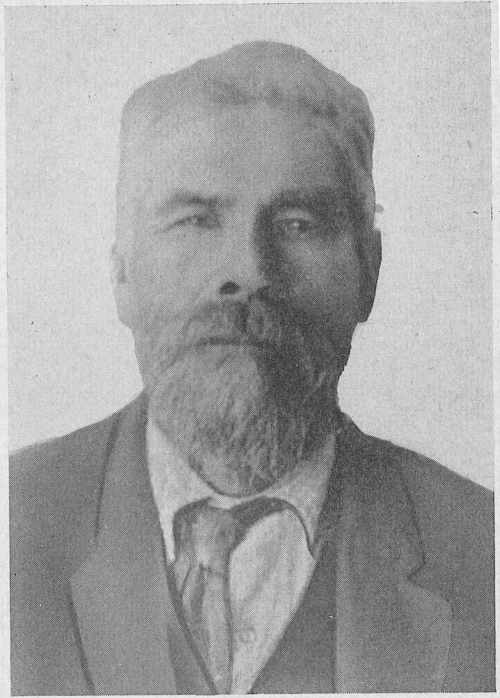

Author: William Bleasdell Cameron (1862-1951)

Date first posted: December 11 2012

Date last updated: Decemeber 11 2012

Faded Page eBook #20121217

This eBook was produced by: Stephen Hutcheson, Ron Box & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

WM. BLEASDELL CAMERON

by

WILLIAM BLEASDELL CAMERON

Author of When Fur Was King, etc.

With a Foreword by

OWEN WISTER

PUBLISHED BY

KENWAY PUBLISHING COMPANY

CALGARY, ALBERTA, CANADA

COPYRIGHT, 1926,

by

WILLIAM BLEASDELL CAMERON

FIRST PUBLISHED, 1926

SECOND EDITION, REVISED, 1927

THIRD EDITION (AMERICAN), 1928

REVISED EDITION, 1950

Printed by

The Wrigley Printing Company, Limited

1112 Seymour Street, Vancouver, Canada

To the Memory of

MY MOTHER

The point about this thrilling story is that it is truth well told.

Mr. Cameron is a trained writer, whose frontier hero, Jim Vue, led me a good thirty years ago to welcome his fiction. This time he narrates his own terrific adventure. When he asks while his fate hangs in the balance—

“Can anyone realize how sweet life really is until he comes near to losing it?”—he is recalling what he felt when his dead friends lay about, and Wandering Spirit exclaimed in the council tent:

“Ah-ha! He has done me favors, too,” and saw the chief hold out his hand.

Suspense lasts up to the trial, and the final moments of Wandering Spirit. This Indian, in his fashion, struck for his own, as the white man has often struck in his fashion.

Much truth that lay in the West, ready for competent tongues, has been stuttered; much of the brief, wild life of Canada and the United States has fallen into the hands of quack writers, who daily delight a legion of quack readers. Happily, we are not all quacks, and many will find Mr. Cameron’s account of this deadly uprising an absorbing footnote to history by the only man who escaped with his life.

OWEN WISTER.

Philadelphia, 1929.

That wide and splendid land, dominated only yesterday by the elements, but now in thrall to the use of man, the pioneer West, has been the stage for many a grim and stirring drama. This is the story of one of them, the record of an event known today as the Frog Lake Massacre.

I was present at the Frog Lake Massacre and escaped by the slim margin of one hundred paces the fate that overtook my hapless fellows. For months afterward the unexpected report of a gun put my heart in my mouth, painted savages plunged in my dreams at early dawn through belts of dark firs upon my flying footsteps, bullets sang in my ears or found their mark in my flesh, and I awoke gasping and unable in the first few seconds of consciousness to convince myself that it was not all a horrible reality. Looking back on that now distant date and thinking over the flow of perilous turns in events piling swiftly one on another, the more clearly than ever before I see how close was my brush with death and wonder that I came through it and lived.

The story is a plain one and it will be told plainly. And if the dramatic setting, the romantic atmosphere of a wild and lonely land, the smoke of teepees and the native eloquence of men, naked and brown as leaves in autumn, do not invite the seeker of the sensational and melodramatic in literature, the tale is not for him. And first, a word about the setting.

Frog Lake, a shimmering expanse of blue water, lies ten [xii] miles north of the North Saskatchewan river, with which it is connected by a creek bearing the same name, in what is now the province of Alberta. The settlement—to dignify it by the name—lay at the foot of the lake. There were the buildings of government Indian agency, the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post, the Roman Catholic mission, and the store of a “free” trader named Dill. On the creek, two miles away, a dam under construction marked the site of a small grist mill waiting to be built for the Canadian Indian Department. The contractor, John C. Gowanlock, lived with his young wife in a log house on the bank of the creek nearby, and his clerk, William C. Gilchrist, lodged with his employer.

Clustering about the lake were the reserves of several bands of Indians. The Cree nation is divided into two branches, Wood and Plains Crees. The former—whose property these reserves were—differed widely in character and mode of life from their brethren of the plains. They were solitary hunters and trappers afoot, the mainstay of the Saskatchewan valley fur trade, and they had lived for generations at peace with the white traders and the missionaries. Their hunting territory was the wooded country north of the North Saskatchewan river and they seldom ventured on the plains to the south among their more truculent kinfolk.

The Plains Crees, on the other hand, pitched their lodges in the great open territory between the North and South Saskatchewans, where in companies and mounted they ran buffalo and waged incessant war against their hereditary foes, the Blackfoot. But their hands were against those of almost every neighboring tribe as well and they made frequent raids into the lands of these enemies and were in turn raided by them. They were better orators, more crafty, savage and daring than were their relatives of the woods.

Still farther to the north lay the territory of yet another [xiii] race of fur hunters and trappers, the Chippewyans. These Indians, while, like the Apaches, of the widely-distributed Athapascan stock, had none of the aggressive characteristics of that formidable tribe; they were a timid people who would do anything but fight and they were in subjection to the Crees.

This book was originally named The War Trail of Big Bear, a title I have long since recognized as inappropriate and misleading. In this fourth edition it has therefore been given a new title, Blood Red the Sun, one which fits, as will be seen in the development of the narrative.

The foregoing particulars will be an aid to the readier understanding of what follows.

W. B. C.

Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan,

February 1, 1950.

On a bright morning in October, 1884, the Plains Cree Indians of Big Bear’s band were in camp on the high bank of the North Saskatchewan river above Fort Pitt. They were assembled to receive their annuities, which would be paid at Pitt on the 20th of that month. Under the treaty the chiefs received twenty-five, councillors fifteen, and all others—men, women and children—five dollars in each year “while grass grew and water ran.”

Fort Pitt was an old and important trading post of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 150 miles east of Fort Edmonton and 35 miles southeast of Frog Lake. George Dill and I had made the rounds of the payments at the various reservations with a trading outfit in competition with other traders for a share of the Indians’ crisp new notes. Now our tents were pitched near the Indian lodges in readiness for the business that would follow the last and largest payment, that to Big Bear and his band. The Indian’s day of affluence is soon past; his money is gone almost as soon as he receives it.

A new prophet and champion had arrived in the band. I had met Little Poplar a few days before. He had come from Pitt to Frog Lake with an order on John Delaney, farming instructor there, for provisions. I learned later how [2] he had obtained it. On the trail he had met the government inspector of Indian agencies. The following dialogue ensued:

Little Poplar: “Who are you?”

Inspector: “I am an officer of the Great White Mother, and I come from the Pile of Bones—Regina. Each year I go around all the reserves to see how fast the Indians are learning the white man’s road—how to make things grow on the land so that they soon will have plenty to eat. They should, of course, also get help when they are sick or in need; flour, kookoosh. I look into these things. I’m an inspector.”

Little Poplar: “Hai! I’m glad to hear that. I’m an inspector, too, and it is meewassin when we two inspectors meet. I’ve just come from the country of the Long Knives to see how my people are treated by the officers of the Great White Mother and the first thing I see is that they are hungry. Some are sick. I think you don’t look very good; your eyes maybe they don’t see good. Give me a musinagan to the man at Frog Lake who is teaching them to grow things—a paper. Write in it that he will give me, Kah-meet-u-sis, 30 bags of flour, ten bags of bakin, tea and sugar for my hungry and ailing people. That will be good medicine!”

Inspector Tomah was not accustomed to being addressed in such arrogant fashion by the government’s red wards and he was not pleased. He picked up the reins and spoke to his horses. The Indian put an arresting hand on the reins.

“No, don’t go yet. First give me the musinagan. And keepah—hurry!”

The objection of the inspector to being delayed prevented an immediate eruption of wrath and Little Poplar got the order.

I was standing beside Farming Instructor Delaney at Frog Lake when Little Poplar drove up with his Crow brother-in-law. He was a handsome Indian. Above medium height, with clean square-cut features, full jaw, long plaited black [3] hair, quick tongue and cool aggressive manner; his whole appearance stamped him at a glance as a savage with whom a white man, to deal successfully, must possess exceptional tact and assurance. A fancy blanket belted at the waist draped his erect, muscular figure and beneath it he wore profusely beaded leggings and moccasins and a wide leather belt from which hung a heavy buffalo knife and a Colt revolver. On his head was a broad Stetson hat encircled by a brass band with an eagle plume stuck in the side and on his wrists brass bands and in his ears huge brass rings.

He made no mention of the order, but stepping up to Delaney he said curtly: “I want 30 bags of flour, ten bags of bakin, ten pounds of tea and 50 pounds of sugar.”

Delaney looked at him curiously. “I don’t know you,” he said; “don’t even know whether you are in treaty. We don’t give provisions even to treaty Indians whenever they take a notion to ask for them. To strange Indians and those not in treaty, we give none at all.”

Little Poplar’s lower lip stuck out; “Why doesn’t the Great White Mother send us agents who are brave enough or strong enough to do things? It is men like you”—he looked insolently at Delaney—“who cause trouble between the Indians and the police like the near-fight at Poundmaker’s last summer.”

He drew from under his blanket the inspector’s order and handed it to Delaney. “Now, do I get the provisions?” he sneered.

Of course he got them. Intensely irritated though he was, Delaney nevertheless was obliged to obey instructions. The supplies were loaded into the carts that had trailed Little Poplar and he returned to Pitt. T. T. Quinn, the Indian agent, followed a day or two later with the cash for the payment to Big Bear’s band—and here the story is back to the point at which it began.

Little Poplar has been introduced thus early in order to [4] show the class of men who led what had long been recognized as the most turbulent and aggressive band of savages in the Canadian Northwest, and because his influence and that of other chiefs served to foment the discontent and restlessness in their followers which was so soon to culminate in one of the most shocking tragedies in the record of the Canadian government’s relations with its Indian wards.

On October 19th Agent Quinn sent word to Big Bear that he would pay the band at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post in the morning.

The Indians arrived promptly. They filled the office in the big fort building where Quinn was seated; they packed the hall, the stairs, the doors and the open windows and trailed away into the square between the buildings outside. All were painted and carried guns concealed under their blankets.

Little Poplar was first to speak. He had come, he said, from across the Line, come to see his people, do something for them. He had heard that they were hungry. That was so. The Americans treated their Indians better; gave them more to eat, more clothing. He would not speak much now. He would hear the others. After that he would speak.

Wandering Spirit, war chief, spoke next. He lamented the disappearance of the buffalo, the red man’s one friend, and the Indians’ destitution, contrasting it with the abundance of the past. Other leaders followed, speaking in the same train.

Then Little Poplar rose again and walking out in front of Quinn asked loudly: “Are you Kapwatamut?”

Quinn raised his eyes. “That’s what they call me.”

“May I look at you?” the Indian went on.

Quinn got to his feet. Six and a half feet tall, spare, athletic, broad-shouldered, exceedingly active, Thomas Trueman Quinn was a splendid figure of a man. A native of Minnesota, notwithstanding his mixed Sioux and Irish-French [5] blood, he was well educated, exceptionally intelligent, and had served with distinction in a Wisconsin regiment throughout the American civil war. Afterward he had seen many exciting adventures while employed as a scout with the regular army in frontier Indian campaigns. It was from his knowledge of the Sioux language that he had received from the Crees his name of Kapwatamut or The Sioux Speaker.

He rose leisurely, turned completely round before Little Poplar and sat down again. He looked at the Indian. “Seen all you want?” he asked.

The Indian scowled. “I have heard of you!” he retorted. “Away over the other side of the Missouri river, I heard of you. I started to come this way and the farther I came the more I heard. You’re the man the government sent up here to say ‘No!’ to everything the Indians asked you!”

Little Poplar bent over and shot the last sentence at Quinn like a slug from a catapult. There was intense silence in the room. The agent signed to him to proceed.

“Now, I am going to ask you something. I will ask it three times before I sit down. It is long since the buffalo went away. My people are hungry and would like to eat fresh meat again. Will you kill an ox before the treaty money is paid?”

Quinn shook his head. “The government gives cattle to the Indians for work and milk, but not to kill. There’s no beef for you.”

Little Poplar went on: “I crossed the Line and travelled north. After a time I came to where the grass had been torn up, and two iron lines had been laid down and stretched away east and west as far as I could see. I said to myself, ‘What is this?’ I thought for a moment; then I said: ‘Hai, yes; I know! This is the pewabisko meskano, the iron road that the government has made to carry food and clothing in their big wagons to the poor starving Indians.’ And I [6] want them to bring money out the same way in the big wagons and to throw it out on both sides of the iron road so that everybody can have plenty of it!” He turned again to Quinn. “For the second time I ask: ‘Will you give us beef?’”

“I’ve answered that question. You heard what I said,” replied the agent.

“’Namoya,’ itwayo! ‘No,’ he says. Akwusee keeam! Very well!” Little Poplar raised his voice. “We will have the government make a telegraph line from here to Battleford, and”—he raised the lash in his hand—“I will whip the wires as they do and we will have him taken away from here! I will have a new man sent in his place before the moon grows old again. I know the government has given orders that beef is to be given us, but he won’t follow them. . . . I look around me,” he went on, “and of all the leaders who stayed when we went south, how many are left? I see one old man!” He placed a hand on the white head of Chief Keeheewin, then faced the agent. “For the third and last time I ask—and when you answer, speak loud so that every Indian in this house can hear you: Will you give us beef?”

“No!” came the reply in the deep voice of the agent.

Instantly Little Poplar faced about. “Go!” he shouted, raising his arms. “Let him keep his pikoonta money! Neeuk!”

And with yells of defiance the whole band swept out of the house, across the square and up the hill, firing their guns in the air as they went.

That afternoon the Indians danced the war dance and Big Bear made a speech. He attacked the government and the Hudson’s Bay Company and, ignoring the other whites present, walked up to Captain Francis J. Dickens, son of the novelist, commanding the North West Mounted Police at Fort Pitt, and held out his hand.

“You are a man,” cried Big Bear, “whom Manito made to [7] be a chief! We like you; your heart is good. As for that man”—he pointed at Quinn—“his heart is made of stone. He may go back to Frog Lake. When the governor made the treaty with us, we were told we should have beef to eat at every payment.” He placed his hands, fingers extended, on either side of his head and turned fiercely on the agent. “You want my head—take it!” he cried, flinging his open hands in the agent’s face as though delivering it to him.

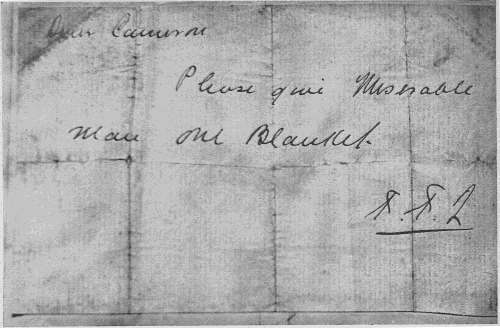

“When I am hungry this winter and ask for food,” Miserable Man said to Quinn, “if you don’t give it to me . . .”

Quinn smiled good-humoredly. He had heard Indians talk before. He did not mind such trifles as their threats.

Big Bear apologized later to everyone for his harsh words, but for two days the band danced the war dance and refused to be paid. The Mounted Police were kept constantly under arms in anticipation of trouble, and Quinn sent his half-breed interpreter to notify the chiefs that unless they came to terms he would return the following afternoon to Frog Lake.

Meanwhile the Hudson’s Bay Company officer, in charge at Pitt, Angus McKay, having made large advances to the band, grew anxious about his debts. He ordered a steer to be slaughtered and sent as a gift to the Indian camp. This mollified the Indians; still, they objected, the beef had not come from the government. They would compromise matters, they said, by accepting the money at their camp instead of at the fort. Quinn decided to humor them and sent word that he would pay them there next morning.

During these days of “strained diplomacy” Dill and I had nothing to do but mind our tent store, fry our bacon, watch the Indian youngsters’ deft archery and try otherwise to kill time while awaiting developments. The Indians did not molest us. They came, talked, examined blankets, knives, print, shawls, handkerchiefs, rings—all our stock, but without money they could not buy. We were glad to hear a truce declared.

At 8:30 next morning two constables came with the pay tent and pitched it about a hundred yards from our quarters. They were followed in twenty minutes by Quinn, who notified Big Bear by messenger that he was ready to begin the payment. The band was in council. After waiting for some time, Quinn walked over to our tent.

“In twenty minutes it will be ten o’clock,” he said, looking at his watch. “If they don’t show up before then they get no money.”

He returned to the pay tent. A little later he passed our place carrying under his arm a box sealed with red wax. It contained the annuity money—seven thousand dollars.

He had scarcely disappeared in the direction of the fort when Big Bear, Wandering Spirit, Little Poplar and other chiefs came rapidly toward our tent. They were talking excitedly and stopped a moment to ask what had become of the agent. We told them he had got tired waiting and had probably gone to dinner. Gesticulating angrily and with exaggerated expressions of amazement, they went on. They overtook him before he reached the fort and persuaded him to return and make the payment.

For the next two days I was busy at the store. The Indians danced and feasted and I went once or twice at night with Stanley Simpson to the dancing lodge and heard Little Poplar count his coups and tell how, using me occasionally and not altogether to my liking, as he swung his heavy Colts pistol in my direction, as representing the enemy, he had taken Blackfoot scalps. Then Dill went to Battleford, 90 miles away, to deposit our funds and bring back a fresh stock of goods, while I returned to Frog Lake and put up a log building for our winter trading quarters. Soon after Dill’s return, by mutual agreement, we dissolved partnership. He continued what had been our business and I accepted a position with the Hudson’s Bay Company at Frog Lake.

Let me go back a step to the reservation, on the Battle River south-east of Pitt, of Chief Poundmaker, where Big Bear was then in camp, and relate a happening there three months earlier that throws a yet more significant light on the attitude of these Indians than the events just recorded. I did not witness this, being a few miles away, and I am indebted to Major Fred A. Bagley, a veteran of the N.W.M.P., and to Mr. William McKay, of the Hudson’s Bay Company, both of whom were active participants on the ground, for the details of what at more than one critical juncture threatened to end in a bloody debacle.

Kahweechetwaymot, a member of Big Bear’s band, went to John Craig, farm instructor on the reserves of Chiefs Poundmaker and Little Pine, and asked for provisions for a sick child. The government furnished supplies to be issued when the need was evident to sick and destitute Indians, but Kahweechetwaymot did not get any. This was hardly surprising to anyone knowing Craig and the Indian. The one was a phlegmatic easterner; the other a pestiferous and not particularly intelligent savage. Anyway, Craig was doubtless following instructions; the Indian did not belong on Poundmaker’s reserve—though some of the more politic [10] of the government’s agents were wise enough on occasion to forget them.

Kahweechetwaymot went off, but he was back in no time—with two aides. One was his brother. The other was a well-seasoned hickory axe-helve.

With these reinforcements, Kahweechetwaymot had no difficulty in obtaining all the provisions he required, which was considerably more than he would have been satisfied with in the first place. Craig arrived at the police barracks in Battleford some hours later, sore from the top down, inside and out, and gave Kahweechetwaymot a very bad name. Superintendent Crozier of the N.W.M.P., commanding at Battleford, sent Corporal Sleigh to bring in Kahweechetwaymot. He wanted to explain to him that the Queen felt much annoyed because of his course in instituting a self-administered code of rewards and punishments.

The Indians were holding their annual Thirst Dance on Little Pine’s reserve—making braves. They were there in hundreds, many from distant points. It was a big fete. Kahweechetwaymot was taking a prominent part. His prestige was high. On the strength of his recent disciplining of a white farming instructor, he was by way of being regarded admiringly by the young men at the dance as an example of the real thing in braves.

Kahweechetwaymot scoffed at Sleigh. In fact, backed by public opinion in the form of the assembled tribesmen, he affected an indignant astonishment. How, he asked, was it that a policeman had the nerve to come there thinking to put him under arrest? “Go back,” said he to Sleigh, “and tell the Big Police Chief what I said.”

Sleigh sent a man to town to report and Crozier realized that the situation was one demanding the personal attention of the Big Police Chief. It was beneath the dignity of Poundmaker and his fellow chiefs, he concluded, at such a time to discuss matters of any moment with his subordinates.

So at an early hour next day, Crozier appeared with twenty-five men—of whom Bagley, then a sergeant, was one—at Poundmaker’s. They brought with them an Indian, met on the trail, who appeared entirely too ingenuous to be at large. Once they were safely in camp on the reserve, he was liberated. As a matter of fact, he was a spy, sent out by Poundmaker to learn what the police were doing, as Crozier had guessed.

The tents up, Crozier took the police half-breed interpreter, Louis Laronde, and one or two troopers and went to the Thirst Dance camp, three miles away, demanding to know why Poundmaker and the other chiefs had refused to deliver up to his men Kahweechetwaymot, who had offended the Queen by striking one of her servants with an axe-helve.

Poundmaker temporized. He was a most deliberate and dignified personage. He told the big police chief not to be hasty. The sun would not go out; it was still high. It was best that matters of this sort be dealt with in calm discussion.

So all day long, while the big drum boomed and ambitious young braves skewered through loops cut in their chests to rawhide thongs reaching to the top of the big centre-pole of the Thirst Dance lodge, flung themselves frenziedly backward in efforts to break their fleshly bonds and prove worthy to be counted warriors, and while other young men capered round on horseback, singing and shouting war-cries, Poundmaker and his brother chiefs gravely discussed the offence and the offender, while the police chief fumed and fought to control his temper.

The outcome of the deliberations was a compromise, the chiefs agreeing that at about noon next day they would produce Kahweechetwaymot for trial if court were held, not at Battleford, but at a plateau some four hundred yards from the position in which the police had made their camp. The [12] selection of this site was a manoeuvre engineered by the police officer to bring the negotiations under the guns of the improvised fort he intended throwing up.

Following the parley, Crozier dispatched a courier to Battleford, thirty miles away, with instructions to Inspector Antrobus to come with speed and all available men remaining in barracks to Poundmaker’s. A little later Crozier and his force departed for the government warehouses on Little Pine’s reserve, adjoining Poundmaker’s, six or seven miles to the west.

These warehouses contained all the stores, bacon and flour chiefly, on the two reserves. Crozier was decidedly against these stores falling by any chance into the hands of the Indians in their present mood. With four loaded ox-teams he started back to his camp at Poundmaker’s.

The Thirst Dance camp straddled the trail, part of the two or three hundred lodges being pitched on either side of it. To avoid the Indians, Crozier detoured to the south of the trail with the wagons.

The Indians were watching him. When opposite the camp a hundred young bucks, mounted and singing, burst suddenly upon him, circling the wagons and firing their guns over the heads of the little force. The idea of the police marching off with the provisions did not please them. Doubtless they had had these in mind themselves. The position was an uncomfortable one, but the police ignored the warlike demonstration staged for their benefit and marched on. At dusk they reached the camp at Poundmaker’s with their loads.

Here were some old log buildings. The men were tired, the night was suffocating, the mosquitoes were a plague and the commissary had fallen down on its job—without the wagons they would have had little to eat—but there was no rest for the little company. Crozier ordered all buildings but one to be torn down. Of the logs so obtained he directed [13] the construction of two rough bastions, abutting on the remaining building. The night dragged but toward morning the job was finished, the sacks of bacon and flour had been piled in tiers behind the log walls to serve as breastworks and the weary men stretched themselves on the ground for a few minutes’ sleep. The completed fort was in this form:

| Log Building | ||

| Bastion | Bastion |

A deep slough behind the fort afforded protection from that quarter.

Inspector Antrobus and Sergeant-major Kirk with the reinforcements, totalling some sixty men, and including a number of Battleford civilians, reached Poundmaker’s about eleven o’clock next morning and shortly after noon Poundmaker and his fellow chiefs arrived in accordance with their agreement at the plateau. Crozier assigned ten men to each of the bastions and leaving the others to await orders, covered by the twenty rifles and taking with him Interpreter Laronde, Constable Campbell Young and another man, went out to meet the chiefs and try Kahweechetwaymot.

Just a month previous the Crees had held a begging dance in the town of Battleford. Those old aboriginal dances were novel and spectacular; they interested us and we all—the whole town, or most of it—looked on. Poundmaker, wearing a breechclout and a vest studded with brass nails, his long legs streaked with white mud, on his head a small cap formed from the dried skin of a bird, was there. Big Bear was there, mounted on a white horse, a rusty black coat on his back and a battered black soft felt hat on his head. The old chief rode up and down before the stores, proclaiming loudly to the world at large that it was meewassin—“good”—here, at Battle River; that it was not “hard” here, when the traders [14] brought out sacks of flour, sides of bacon, packages of tea and sugar and thick plugs of tobacco and piled the gifts on the ground beside the dancing warriors.

Inspector Antrobus came past, riding a tall police horse. Imasees and Okemow Peeaysis, sons of Big Bear, galloped furiously across the prairie directly at the inspector. They carried in their hands folded umbrellas. As they reached Antrobus they jerked their ponies to a stand and the umbrellas flashed open. The police horse snorted, swerved violently, the officer’s pith helmet rose in the air and sailed away over the grass and his startled mount bolted wildly with him for the barracks.

The Indians, looking on, grinned delightedly. Evidently they regarded the incident as a rattling fine joke. The inspector on the contrary could see nothing at all humorous in it.

An hour later the dance was over and the Indians had gone to their camp on the hill south of the Battle River, when Inspector Antrobus, accompanied by William McKay, manager for the Hudson’s Bay Company at Battleford, appeared among the lodges asking for the head chief. Poundmaker indicated Big Bear. The inspector was intensely angry; he trembled with rage.

“I have not much to say,” he announced wrathfully, “and my message is for the head chief alone. Let no one else speak.” He turned to Big Bear. “What are you doing here? You have no business in town. Unless you are packed and on the trail back to the reserves in half an hour, I will put you chiefs under arrest and lock you up.”

Amazement for the moment held the Indians. Then Poundmaker, his dark face flushing, jumped to his feet.

“There will be a bullet here,” he declared loudly, a hand at his throat, “before you arrest one of us! When we are ready we will leave; not sooner.”

An old man got up. “He says no one must speak but Big [15] Bear!” he cried. “Well, I am speaking. Let him stop me! Look at him,” pointing at the officer’s legs. Their unsoldierly shaking must have been mortifying in the extreme to Antrobus, who was anything but a timid man, but he could not stop it. Rage exacts its penalties. “And he tells us this!” The old man snorted contemptuously. “’Wus!”

The Indians looked and once more they laughed at the inspector. Antrobus was beside himself. He could not trust his tongue to further words. He climbed into his buckboard and clattered off.

Two hours passed. The Cree camp was still on the hill south of the Battle, but no arrest had been made.

When Crozier went out to meet the chiefs, there was still some difficulty he found about Kahweechetwaymot’s trial. The Indian, backed by the young men, declined to give himself up. They were all wild, said Poundmaker, and it was hard to do anything with them. At another time it might be done, but, Poundmaker pointed out, their pride revolted against a surrender in the face of such a great gathering of their people, many from distant reserves. So the unending talk went on. The police seemed to be getting nowhere. The prestige of the scarlet-coated upholders of the law was at stake. If they gave way it would be many a day before it could be completely regained. The last would never be heard of it. So long as an Indian present remained alive, he would boast and acclaim to his listeners about the camp fire at night of the time they bluffed the police.

Crozier’s patience was exhausted. He quitted the council abruptly and returned to the fort.

William McKay had arrived from Battleford about noon. The McKays had been Hudson’s Bay Company officers for generations. They had been given by the Indians the family name of Little Bearskin. They were known to every Indian along the Saskatchewan. A Little Bearskin to these Indians [16] was a man to be trusted. The McKays possessed their confidence.

Poundmaker rose. “I am going to the fort,” he said. “If I can prevent it there will be no bloodshed. Since this man will not give himself up, I will offer to take his place.”

Big Bear ran after Poundmaker. “N’chawamis,” he cried, “you will not be left to face the danger alone. If you go, Big Bear goes also.”

Together the chiefs entered the fort, but came out a moment later. Crozier would not accept a substitute, they told McKay; he would take only Kahweechetwaymot. The three seated themselves on the grass before the fort to smoke and endeavor to find a way of surmounting the difficulty. Crozier sent a messenger to McKay, asking him to detain the chiefs.

“Tell Major Crozier I’m no policeman. If he wants the chiefs, let him hold them himself,” was the Hudson’s Bay man’s answer. He was not pleased.

Big Bear was taking little part in the discussion. He watched the fort. Suddenly he exclaimed. “Something is going to happen. Look!”

The police had emerged. They were buckling on their sidearms and saddling their horses. Poundmaker rose hurriedly.

“If there is to be trouble, my place is with my men,” he declared, and followed by Big Bear he ran back up the slope.

The police advanced slowly, the sun flashing on their polished carbines, their scarlet coats aglow. They lined up before the Indians, a soldierly and formidable-looking company. That they could be relied on to give a good account of themselves was not to be doubted.

Sergeant Bagley had been assigned to one of the bastions. He glanced over at the corral, and saw “’Andsome ’Arry,” the solitary remaining horse, Bagley’s trooper.

“You’re in command here,” he told the corporal beside [17] him; “I’m resigning,” and disregarding orders he slipped over to the corral, mounted and joined the line out in front.

Crozier confronted the tall chief, to whom the Indians were looking as their spokesman. This was his land; Big Bear was taking no prominent part. At the officer’s request, McKay acted as interpreter.

“Poundmaker,” he announced, “I came out for this man and I am going to take him.”

The Indian thrust out his long face. His black eyes kindled, passion shook him and Bagley, watching, saw him strike, seemingly unconscious of what he did, with the sharp points of the knife-blades in his pukamakin, at his right leg. Blood welled out and flowed down the legging. His cloak of friendliness, for apparently it was a cloak, fell away and he stood revealed, a hostile among the hostiles.

“He won’t be given up!” he declared vehemently, stamping his foot. “You say you are going to take him?” He lifted a tapering forefinger and tapped his chest. “Take me first—if you dare!”

Antrobus stood near. He glanced at the chief and passed a slighting remark. It was not understood by Poundmaker but he guessed its import. He was infuriated. He had not forgotten the inspector or his threat at the begging dance the month before. He lost for the moment his accustomed restraint. Raising his pukamakin, he rushed upon Antrobus. The three knife-blades in the end glittered above the officer’s helmet.

“Redcoat dog!” he hissed.

But Constable Prior poked his carbine in the tall chief’s face and the deadly pukamakin dropped slowly to his side.

Suspense gripped the Indians. A deep hush had fallen. Now the reaction came. The excitement rose to an uproar.

“Plenty blood will be spilled on the banks of the Cut-Knife to-day!” shouted Imasees.

Some minor chiefs, peaceably disposed, appalled by the [18] impending explosion, rode among the mob, waving green branches, imploring the aggressors to be reasonable, to consider before it was too late. Their example had some effect; the storm sank to a murmurous undercurrent. But in a moment it rose again, more violently than ever. The hostiles surged around, jeering, whooping, raising their guns threateningly, goading the police with taunts and epithets.

Wandering Spirit, who in the war dance counted thirteen Blackfoot scalps, rushed out and seized McKay by the wrist, endeavoring to drag him over to the Indians’ side.

“Come!” he urged frenziedly. “You are crazy. You will be killed!”

McKay pulled away.

Little Pine, amiable and friendly always, sitting his horse, addressed the mob. They were wrong, he told his people, to defy the police. He was a notable chief, a warrior as well as an orator of parts, and he spoke forcibly and at some length. But they heard him with impatience. They had reached the stage where pacific words were almost an offence. Little Pine died shortly after the trouble. Rumor had it that poison was responsible; that he paid with his life for the stand he took that day in opposing the more turbulent among the bands.

Sergeant-major Kirk sat like a statue on his horse in front of the line, gazing stonily ahead. At his horse’s muzzle stood Wandering Spirit, muscles tense, dark eyes agleam, thin lips working, his lean claw-like hands gripping a Winchester. When the din was at its peak, Bagley saw the Indian strain and lift as though struggling under some ponderous weight and the rifle came up. Bagley held his breath.

“Now it’s coming! Now old John’s going to get it!”

The words said themselves over and over in the sergeant’s mind.

The blood-lust burned in the war chief’s eyes, dull red pools glowing murkily in their sultry sockets. The seconds passed. What was restraining him?

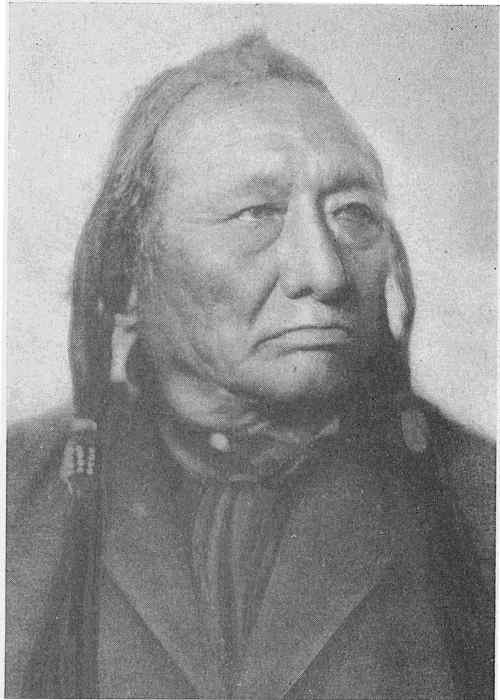

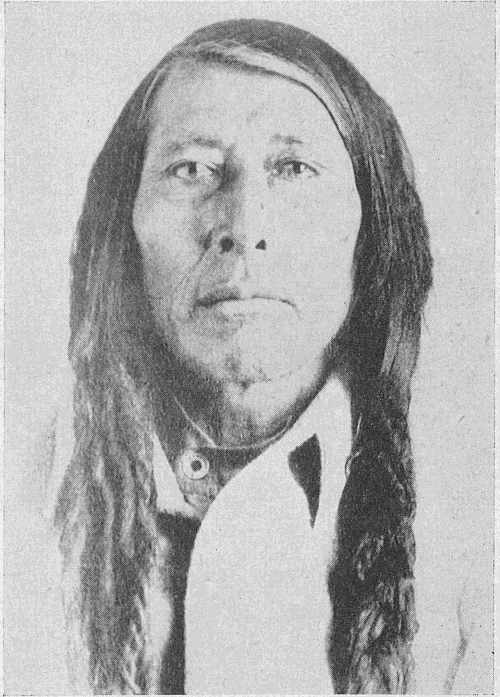

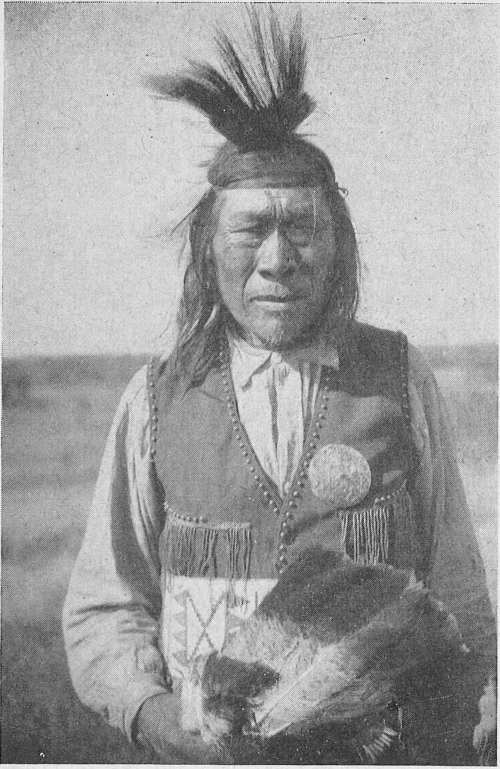

BIG BEAR,

Chief of the Plains Crees.

The sullen tide beating against the tough barrier that had so far contained it—the counsel of leaders able and tried, accustomed to being deferred to—might at any moment burst through. The pressure of a finger, red or white, against a trigger and a flood would descend that would drench that sunlit slope in waves of crimson death.

It was as if the war chief were stretched on a rack of conflicting emotions—the hunger to kill that was his consuming passion and a foreboding that made him pause. Should he be the one? Dare he take upon himself that sinister responsibility? Did he see confronting him the vision of a day of reckoning some time to come, a day when the white man would exact the ultimate price?

The old police warrior never flickered an eyelash. And when the lull came the rifle was lowered again. Bagley breathed once more. Then came the renewed uproar and again the menacing rifle lifted.

Miserable Man rode round behind Kirk. “I will fight with the police!” he declared loudly. But he had no intention of fighting on the side of the police. Miserable Man was a dissembler. His purpose was to make sure that, between himself and Wandering Spirit, the sergeant-major should not escape. To take the scalp of an officer would be greater glory than to tuck under his belt that of an ordinary policeman.

An Indian rode over to the depression on the left of the police line. “Keep quiet, there!” Bagley heard him say. And it came to the sergeant then that all along he had been conscious of a droning murmur of women’s and youthful voices and he sensed the grim menace that lurked in the wooded hollow.

The clamor fell and rose once more and once more the threatening rifle of the war chief came up. But again it came down unfired. Why, as will be evident before this narrative is ended, is an eternal riddle.

Crozier turned to Laronde. “Which is him—the man we want?” he asked.

A tall Indian, a sneer on his evil face, Cree words of contempt on his lips, danced and cavorted in the van of the mob. The interpreter pointed.

“That’s him.” And as the Indian, noticing, dived suddenly among the others: “There he goes!” he added.

McKay called to him and the Indian came out. Said the Hudson’s Bay Company officer:

“Tell the police okemow you will surrender. You will get a fair trial. You may be punished but they can’t hang you. If trouble starts the police will not be the only ones to suffer. Many of you will die also. Do you want to see that? Be a man! Give yourself up!”

“I won’t!” returned Kahweechetwaymot surlily.

Twin Wolverine, Big Bear’s eldest son, pushed his horse into the police line beside Constable Campbell Young. “I am going to fight against you!” he shouted to his fellow-tribesmen. Unlike Miserable Man, the Twin Wolverine meant what he said.

McKay turned to Crozier. “Arrest your man,” he advised.

“Think we’d better do it now?” queried the officer.

“Yes. The longer it is put off, the greater the danger. There has been too much talk already.”

“The two men afoot on the right, fall out and seize that fellow!” came the command.

Kahweechetwaymot wheeled to run. “Nab him!” McKay prompted Laronde. The interpreter rushed and seized Kahweechetwaymot. The two policemen followed. Before the Indian realized how it had all happened, Constable Warrent Kerr—“Sligo” to the force—had Kahweechetwaymot by the long plaits of his black hair and had landed him with a swing that had nothing gentle about it among the policemen on foot. They closed about the prisoner and his captors. The horsemen quickly encircled them and the whole [21] body began to move off, the men in the rear facing backward with their carbines ready for instant action.

McKay paced evenly up and down between the two rows of levelled rifles.

Bedlam broke loose. The Indians went wild. “Shoot them, shoot the red coat dogs!” they howled. “Why do we wait? Now—now was the time we agreed on to wipe out the dog chemoginusuk!”

But the cooler men among the redskins frantically fought the outcries of the hotheads. “No—no! Be careful! Wait! Let the red coats shoot first!” And, referring to McKay, walking coolly up and down between the opposed forces: “Shame! Would you kill a Little Bearskin?”

They brushed past the Hudson’s Bay official and charged the retreating ranks, jostling the men, snatching at their clothing, stabbing their horses with the points of their knives, hoping to stampede them. One man, cut off from the others, was stripped, his tunic and sidearms forcibly appropriated. Poundmaker himself wrested away his carbine.

But the horses, like their riders, held firm. And no Indian fired. Neither did a policeman. Because the police, disciplined and obedient to orders, could not and would not under no matter how aggravated provocation, be first to breach the peace. But if, even by accident under the tension, a single shot had sounded——! What would have followed, no man present during those pregnant moments cares to contemplate.

Maddened over the successful coup of the police, a dozen of the most truculent braves seized Laronde and, powerful though he was, rushed him off through the poplar bluffs. That he, a half-breed with their own blood in his veins, should have aided the enemy—that, above all, he should have pointed out to the police okemow, and later stopped Kahweechetwaymot—incensed them beyond anything else. Laronde’s chances of living seemed exceedingly remote.

The police flung their horses against the ring of passion-distorted faces and at length pushed through and reached the fort. The Indians crowded them, with jeers and epithets, to the walls. Kahweechetwaymot was shoved through an opening into the waiting hands of the men inside and the police followed. The Indians stormed about outside.

McKay drew Major Crozier aside and spoke to him in an undertone.

“Throw out the bacon and the flour!”

The men doubted whether they had heard aright. Pull down their defences, their breastworks? He could not mean it.

“Throw out the bacon and flour!” There could be no doubt about the command this time. “Look alive, men!” the commandant added.

The heavy sacks went over. The effect was magical. The angry clamor died. The camp was a huge one, its food supply scant. The Indians were hungry. In the surprise of sudden abundance they forgot their quarrel with the redcoats. They pounced upon the sacks, each struggling to secure a share before he was too late. The women and boys came from their place of concealment and joined their men in the raid. They lugged the stuff off through the bluffs to their lodges. The suggestion had been McKay’s and his strategy was a winner. He knew Indian character.

And while the Indians, unheeding, fought over the spoil, the police bundled a most subdued and crestfallen brave into a wagon and in half an hour were on their road with him to Battleford.

After all an Indian, take him by and large, is nothing but a grown-up child.

Laronde turned up as they were leaving. Again McKay had intervened. “Let him go!” he had insisted. “Don’t blame him; he’s paid to do this work. That’s how he makes his living. If you want a prisoner, why don’t you take the police okemow?”

McKay knew that he was safe in making what at this stage was a perfectly impractical suggestion.

Before the police left, McKay hunted up Poundmaker.

“You must surrender the rifle you took from the policeman,” he told him.

Poundmaker’s quick temper flared again. “I will not!” he exploded. “He was going to use it against us!”

“Now, see here.” McKay talked patiently to the handsome red man as he might have done had he been explaining some puzzling matter to an angry boy. “You must not look at this thing in that way. The gun did not belong to the policeman. It does not belong to the police at all. It belongs to the Queen.”

Poundmaker pondered this. Three years before he had guided the Marquis of Lorne, Governor-General of Canada, three hundred miles across the plains from Battleford to the Blackfoot Crossing. Poundmaker was an unusual Indian. He was the typical chief as one has been accustomed to picture him from the literature of his youth—tall, dignified, deliberate in speech and manner, his striking face framed in a setting of raven-black hair hanging in two immense plaits far below his waist, with a certain native air of courtliness and distinction that impressed all who met him. No wonder that Lord Lorne had made much of the stately red man. Perhaps that was why Poundmaker held the governor-general in some respect. He did not wish to displease the noble lord’s mother-in-law, the Queen. So in the end the gun was surrendered.

Half a dozen of us, civilians, were on our way from Battleford to Poundmaker’s reserve. The parley out there had lasted three days. We had heard in Battleford that the situation was critical. The addition of a few rifles might be acceptable to the police, we thought.

The afternoon was intensely hot. We had off-saddled half-way out to breathe our laboring horses and enjoy the [24] poplared shade and clear cold water of Medicine Drum Creek. A horseman hove in sight, coming from the direction of Poundmaker’s. He came up.

“The fun’s all over, fellows,” he told us. “They’re on their way in with their man. You might as well go home.”

In this and the preceding chapter I have endeavored to show Big Bear’s band in a characteristic attitude of hostility to the government. The leaven of mischief was already at work; they were prepared to start, with all the inherent cruelty of the savage, on a course of rapine and bloodshed at the first favorable opportunity. How soon that opportunity was to arise the handful of white men who had made their way into that primitive corner of the far North-west beyond the Saskatchewan could then have small conception.

When in the year 1875 the Saskatchewan Indians met the commissioners appointed to treat with them for the cession of their rights, the only chief of importance to refuse the proposals made by the government was Big Bear. Acceding probably to the demands of the more unruly element in his following, he gave as a reason his objection to the white man’s law which permitted hanging. He also wished, he said, to see how the promises made to the tribes would be kept by the government.

The action of Big Bear in thus declining to subscribe to the document surrendering his country and his liberties to the white man’s dominion gathered about him the independent spirits among his people and he soon came to be recognized as the most powerful chief of the Cree nation.

While the buffalo continued plentiful the band lived much as they had done before emissaries had come from the Big White Mother to buy their heritage. They became a band of nomads and drifted south, across the line into Montana. The buffalo, mercilessly hunted for their robes by white men, soon disappeared; Big Bear and his followers became a menace to the ranchmen of the Treasure State and were driven back into Canadian territory. Reduced to the [26] extremity of want and wretchedness, in 1879 at Sounding Lake, Big Bear at length affixed his mark to the treaty.

But though they had come into treaty, Big Bear’s band obstinately deferred following the example of the others and selecting a reservation. They excused their tardiness on the plea that there were so many fine locations it was hard for them to agree on a choice. Thus while reservation Indians when in need—as often happened—got help from the government, for Big Bear there was no such provision. During the first winter—1883-4—they did, as a matter of fact, get a few supplies from the Indian agent, but this was in payment for work done. With the advances they received from the Hudson’s Bay Company on account of their treaty money and furs and game they killed, they managed to live through the winter.

The following summer, as has been seen, found them at Poundmaker’s reserve, where the incident just related—the flare-up precipitated by the ruffianly Kahweechetwaymot—occurred. Shortly after this affair Big Bear’s band returned to Fort Pitt for the payments already described, and this brings the story to the winter of 1884-5. During the spring of 1884 while trading on my own account among the Saskatchewan reservations I had spent some time at Frog Lake. I was, therefore, no stranger to these Indians when I returned the following New Year to take up residence in their territory in a new capacity.

The months of January and February passed uneventfully. Big Bear and his band were camped in the timber along Frog Creek not far from the mill site. They cut wood for the police detachment, freighted for the Hudson’s Bay Company and got some occasional help from Indian Agent Quinn.

The old chief often had dinner with me; thus I had frequent opportunities to study his deeply-lined, intelligent face. Big Bear was then perhaps sixty years of age. He had an amazing voice and when he talked, as he often did, with [27] his right arm free and the left holding the blanket folded across his broad chest, with the dramatic gestures and inflections natural to him, he reminded me of an imperial Caesar and was one of the most eloquent and impressive speakers I have ever listened to.

On my trips to Pitt during this period I spent several days with Mr. W. J. McLean, chief officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company for the district, and his hospitable family. We played cards, danced, sang, took snowshoe tramps, organized rabbit hunts. I made the round of his trapline across the big river from the fort once or twice with Stanley Simpson and helped him to bring in seven foxes.

About March the first rumors reached us of impending trouble between the government and the French half-breeds at Duck Lake. Louis Riel, who had incited the rebellion among these people in 1870 and been outlawed for his action, was again their leader. We had, in fact, known earlier that half-breed runners from Duck Lake had visited Big Bear’s band, but had not anticipated any serious outcome. The half-breeds claimed their title in the country had never been extinguished and professed to believe they were to be dispossessed of their land holdings. They were ripe for hostilities and sought the co-operation of the Indians.

Andre Nault, a French half-breed cousin of Riel, was arrested at Fort Pitt while on his way early in March from Duck Lake to Frog Lake and detained, on suspicion of being the bearer of incendiary messages from Riel to Big Bear, for several days by Captain Dickens. On being liberated he boasted openly that he would soon be in a position to revenge himself on the police. How successfully the rebel Riel, through specious promises, had drawn Big Bear’s lawless followers into a league with him against the whites was shortly to appear. The half-breeds had a logging camp at Moose Creek, twenty miles west of Frog Lake. I have always believed that Nault was a Riel spy.

On the evening of March 28th I closed the trading shop early and, with my skates under my arm, walked over to Frog Creek, intending to skate down to Gowanlock’s. Gowanlock lived in a house near the dam, with his wife and a clerk named William Gilchrist.

The weather had been mild for some days and there was much water on the ice. I had not skated two miles before I was thoroughly wet and decided to go ashore and walk back to the settlement.

The trail took me through Big Bear’s camp. The band was in council. The smoke-blackened tops of the lodges stood among the naked poplars, through the ugly, swinging limbs of which the raw north wind swept in fitful gusts, soughing dismally. Underneath, the rumpled snow softened in the first clasp of spring. The stars hid behind the cheerless grey curtain of clouds overhead. In and out between the lodges slunk stealthy, starving curs, snapping viciously at one another over bones long picked clean.

I noticed the tense, serious looks on the faces of the warriors smoking the long stone pipe round the fire in its centre as I entered the lodge. I saw at once that this was no ordinary social affair. I pulled once or twice at the pipe [29] when it came to me in its course round the circle and I heard and understood, though the talk—in the Cree tongue—was guarded, to make it clear that subdued excitement burned in the breasts of the Indians—that they were contemplating some eventful step.

The talk was of “news”. Wandering Spirit, the war chief, rose and spoke earnestly in his low, impassioned voice and with that transfixing look in his dark eyes that I have never seen in those of any other Indian. Then he drew his shirt over his head and presented it to Longfellow, brother to a Wood Cree chief. Longfellow followed, and he in turn handed his shirt to Wandering Spirit. And all the while the calumet of compact continued to pass from mouth to mouth round the circle. Big Bear’s band, it was evident, was making proposals of some kind to the Wood Crees.

Big Bear was away, hunting in the mountains to the north of Frog Lake with his two sons. Little Poplar, with his family, was at Battleford.

I knew all the Indians well, for I had met them almost daily at the trading post during the winter. But I saw that I was not altogether welcome and I soon left. As I walked home through the slush in the dull and lonely night, I had a premonition of evil days at hand and I felt uneasy and depressed.

It was three days later that we got the “news” the Indians were evidently expecting. I strolled into the mounted police barracks at eleven o’clock at night and found Constable Billy Anderson just arrived with the report of the half-breed rising at Duck Lake. He had ridden the thirty-five miles from Fort Pitt in a little over three hours, through the darkness and the melting snow, across the slippery, hilly country, and his horse steamed sweat. He had brought dispatches from Captain Dickens for the corporal in charge of the Frog Lake detachment, R. B. Sleigh.

The police at Fort Carlton and the Prince Albert Volunteers, [30] said the dispatches, had met the rebels under Riel and Dumont and after a sharp engagement had been compelled to retreat, with a loss of thirteen men killed and many wounded. The Captain suggested that the Indian agent and the other white residents at Frog Lake should come into Fort Pitt. He added that he was ready to come with his men to Frog Lake, however, if we thought that the better plan. The Fort Pitt garrison numbered about twenty.

Anderson had brought mail for the settlement. I was postmaster and walked over to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s post to assort it. Indian Agent Quinn dropped in on his way to the Roman Catholic mission to tell the priest. He asked me to accompany him.

“Well, Cameron, we’ll be pulling out of here before daylight. I suppose you’ll be ready?” he said as we walked along.

I had not considered going, and I told him so.

“There’s a lot of furs and stores on hand here. My chief’s at Pitt and I’m in charge. If he’d wanted me to go in he’d have written. I’m hardly at liberty to leave without orders.”

Quinn stopped abruptly and faced me. “Don’t be a fool, Cameron!” he exploded. “You don’t know Indians as I know them. You’re not obliged to wait for orders to save your life.”

His vehemence surprised me, but I answered stubbornly: “If I felt like that about it, I wouldn’t hesitate; I’d go. But I don’t. These Indians aren’t going to kill me, whatever happens. I’m not trying to influence anybody, though. Anyone who doesn’t feel safe, should leave, I’m thinking.”

Secretly, I hoped they all would leave. I should feel safer alone with the Indians. And I smelled adventure, something that appealed to me. I was young. But as Quinn had said, I did not know Indians. I only thought I did. I realized this a day or two later.

Quinn did not try further to persuade me and we went together to the mission. Pere Fafard was in bed, but he [31] came down and opened the door at our knock. An old man named Williscraft, staying with the priest, was present while we discussed the situation and Quinn proposed to the priest that we join the other whites and leave Frog Lake.

The missionary at once demurred. We should, he said, show that we had confidence in the Indians, now trouble was come.

Because, I suppose, he was a Roman Catholic, the priest’s views upset Quinn’s own better judgment. “Oh, all right, Father,” he said; “if that’s how you feel, I’ll stay, too, though I did think that to go to Pitt would be wisest for us all.”

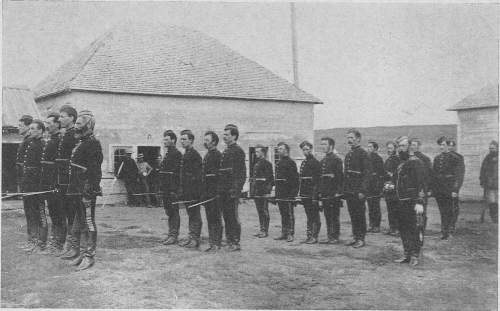

We went in a body to Delaney’s. Besides the farming instructor and his wife, Corporal Sleigh, Mr. and Mrs. Gowanlock, Gilchrist and George Dill were present. The question was debated anew. Father Fafard again voiced his views, and at length it was decided that, with the exception of the police, we should all remain at Frog Lake. In view of the recent reverse at Duck Lake and the known sympathy of the Indians with their kinsmen, the half-breeds, while refraining from advising the others as to their course, I advocated the departure of the police. Six policemen would be no possible protection to us in the event of an outbreak against the overwhelming numbers of the Indians, while if Big Bear’s band was evilly disposed they would begin the trouble by picking a quarrel with the redcoats. Sleigh was ready to go or to stay, as we wished.

Quinn agreed with me. “And, since you’re going, Corporal,” he said, “I wouldn’t lose any time in getting away. If the Indians learned of it—there’s no telling. They might take it into their heads to stop you.”

I said to Sleigh: “I’ve two kegs of powder and eighty pounds of ball over at the shop. It would be as well out of the way. If you’re not too heavily loaded—“.

“Sure,” he said. “We can take it, all right.”

He sent Constable Loasby with me and we brought the [32] ammunition to the barracks. I kept a little powder and a few loose balls were left scattered about the floor. I reasoned that if the Indians rose and asked me for ammunition, it would not conduce to their friendliness to be told that I had none. Either they would suspect me of lying or of having made away with it.

Just before daybreak a double police sleigh slipped out of Frog Lake and disappeared among the hills across the chain of lakes opposite. And I had taken my last leave of Corporal Sleigh, as true a gentleman as ever wore the Queen’s uniform.

When I went to my room at the post to throw myself on the bed for a little sleep, I glanced out of the window. An Indian in a red blanket, rubbing his eyes, hurried along the deserted road in the track of the departed sleigh. Here was fresh “news” for Big Bear’s band.

At nine o’clock I was up again, had had breakfast and gone to the trading shop. It was the first of April. A Big Bear Indian came in. Wandering Spirit was at the farming instructor’s house, he said, and sent word that Agent Quinn wanted to see me. I closed the shop and walked over.

Wandering Spirit grinned as I entered. He wore his war bonnet and seemed in excellent humor. “Big-Lie Day!” he exclaimed. The other Indians present laughed. So did Quinn. I joined them. There were more dupes than one there, that first of April morning, and they were not the Indians.

Imasees, Big Bear’s son, said to the agent:

“Sioux Speaker, we have had bad advice from the half-breeds this winter. They said they would spill much blood in the spring. They wished us to join them. They have already risen; we knew about it before you. They have beaten the soldiers in the first fight, killing many. We do not wish to join the half-breeds, but we are afraid. We wish to stay here and prove ourselves the friends of the white men. Tell us all the news that comes to you and we will tell you all we hear. The soldiers will come, perhaps, and want to fight us. We want you to protect us, to speak for us to their chief when they come.”

Quinn replied: “You make good talk, Imasees. I am glad you wish to remain friends with us. The fighting is far from here. Stay on the reservation and no one will bother you. I will see that you do not want for food.”

Miserable Man joked the agent about his threat in the fall. They shook hands as they passed out.

“I’m glad Wandering Spirit seems friendly,” remarked Quinn. “He has a great reputation as a warrior among the tribes and as war chief is most to be feared. So long as he stays quiet we have nothing to worry about.”

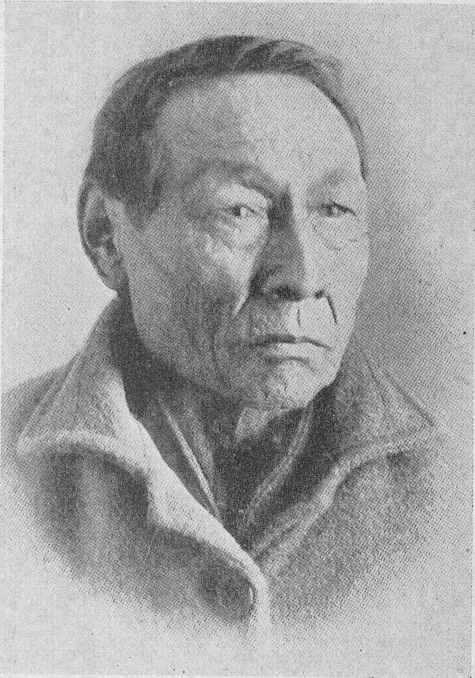

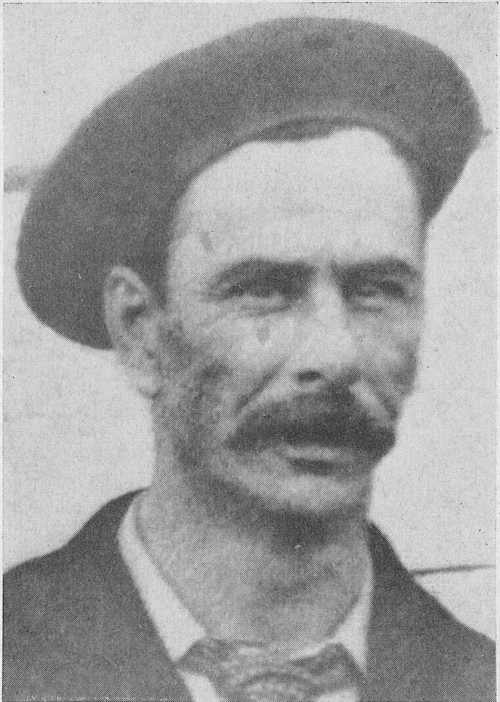

Perhaps it was because I came to know him so well and witnessed the ferocity of his wild, complex nature when roused, that Wandering Spirit has always filled the first place in my memory among the many Indian chiefs I have met. Tall, lithe, active, perhaps forty years of age, of a quick, nervous temperament which transformed him at a stroke in moments of excitement into a mortal fiend, he was a copper Jekyll and Hyde—a savage no more to be trusted than a snake. An odd thing about him was his hair. Whereas the hair of the ordinary Indian is as straight as falling water, the plaits of the war chief, while long and black like any other Indian’s, stood out about his head in thick curls, forming a sombre background for his dark, piercing eyes. And those eyes! Shall I ever forget them? I can see them yet, in all their burning intensity, flashing here and there, seeing everything, as though it were yesterday. His nose was long and straight, his mouth wide and lips thin and cruel. He had a prominent chin, deep sunken cheeks and features darkly bronzed and seamed about the eyes and mouth with sharply-cut lines. His voice was usually soft and intriguing; when he spoke in council it rose gradually until it rang through the camp. It had a smooth, velvet quality that reminded me always, somehow, of the panther he so much resembled in other ways, and of its soft, caressing paw—with the claws of steel beneath the velvet.

“He was never much to steal horses,” Four-Sky Thunder said to me one day later in the camp, when he called with a present of tobacco and we sat smoking in the lodge. “His greatest pleasure was in fighting, and he has killed more [35] Blackfeet than any warrior among us, not excepting Big Bear.”

First councillor, head soldier, war chief, cruel as the grave, a hunter of men, as proud of his record as any gold-laced general of his decorations—Kahpaypamahchakwayo, the Wandering Spirit.

In the evening I walked over to Quinn’s house, dropping on the way into Delaney’s. I found there Gowanlock and his wife, Gilchrist and Dill. They asked me whether Mr. Simpson, my chief at Frog Lake, had returned from Pitt and on my replying in the negative, jokingly remarked that he must be afraid to come out. I answered that if we all had as little to fear as my chief I should feel easier; he had known and traded with Big Bear and his band for twenty-five years and he and the old chief were great friends. I felt, I suppose, unreasonably irritated. Plainly these people did not sense the gravity of our position. It seemed to me no time for flippant talk. True, the Indians had not as yet given us cause for apprehension, but we were at the mercy of their every whim and who could say that a situation of deadly peril and anxiety might not develop at any moment?

I went on to Quinn’s. Crossing a ploughed field beside the house, I almost stepped in the darkness on an Indian. He crawled away at my approach. They were guarding the agent’s house, then! He was not to be allowed to escape as the police had done.

Quinn was seated in his office, just off the front hall. Big Bear, Imasees and one or two others of the band were with him. Imasees gave me his chair, passing a common Indian joke about me, at which all laughed excepting Big Bear. The chief had returned that afternoon from his hunt. His striking face was dark and swollen from the cold and the smoke of many camp-fires and he looked weary and troubled. He was speaking of “Uneeyen”—Riel—the half-breed rebel leader, and went on:

“He said to me, ‘Big Bear, much blood will flow.’ He was [36] trading whisky on the Missouri River and wanted the Crees to help him make war.

“When I was in the Long Knives’ (Americans’) country I had a dream, an ugly dream. I saw a spring shooting up out of the ground, I covered it with my hand, trying to smother it, but it spurted up between my fingers and ran over the back of my hand. It was a spring of blood, Kapwatamut!”

Imasees left the house. His father’s talk seemed to trouble him. The old chief rose. “Good night, Kapwatamut,” he said. He extended his hand, and there was deep concern in his voice as he looked into the agent’s eyes and repeated: “Good night!”

After they were gone, Quinn said: “They seem friendly. Guess they’re going to be all right.”

I answered: “Something’s troubling Big Bear; he behaves queerly. I’m sure no harm’s to be anticipated from him personally. I’d like to feel as sure of the others.”

I remained with Quinn until eleven. He told me of the Minnesota Massacre in the ’60’s, when his father, an Irishman and a noted scout for the United States troops, had been ambushed and killed by the Sioux. Also of his own narrow escape at that time, when the hostiles at grey dawn raided the small frontier town where he was employed in a trading business and he had jumped in an empty barrel and worked it under the counter with his fingers. The Indians had missed him when they sacked the store and he had got away that night. Half starved, after several perilous days and nights he had at length reached a military post. He said to me as I was leaving:

“Well, Cameron, they might kill me, but they can’t scare me.”

Poor Quinn! I wonder if he guessed how soon his courage and his boast would be put to the proof?

Lone Man and Sitting Horse, the uncle and brother of Quinn’s wife, a Cree woman, went to him in the night with horses and offered to see him well on the way to Fort Pitt.

Quinn would not go.

“Pom-pom-pom-pom!”

What is there in man that responds so extraordinarily to the measures of that most barbaric of sound instruments, the drum? Why should the reverberations from a hollow cylinder beaten on its skin-covered top with a stick so powerfully influence the feelings of sophisticated human beings with supposedly disciplined emotions? Is it a legacy from the dim past, this mysterious response, an inheritance from forebears who lived in dens, danced under the moon and doubtless fashioned drums in their first rude assays at achieving melody? Or is it maybe the rhythm, the persistently-recurring thump, the steady staccato monotone impinging with inescapable and hammerlike precision on the chords of that most sensitive human keyboard, the nerves?

We hear in the distance the smart strains of a marching band, the even boom of the drum dominating, setting the pace, and are instantly thrilled. Our pulses quicken, our shoulders lift and almost automatically we stiffen our stride to step in time with the stirring lilt of the music. Or we view the slow passage of a military funeral and listen with bowed heads to the solemn measures of “The Dead March in Saul,” while the leaden thud of the drum falls, like a clod on a [38] coffin, with a grim echo of finality at the end of each stanza, and are profoundly moved.

But of all sounds I have heard that had their source in the drum, none have so moved me as those winging like bats through the heavy air as I walked home from Quinn’s office that memorable first of April night.

It was mild and moist, with thick dark clouds overhead and sullen unrelieved murk beneath. An oil lamp burned dimly, I noticed, in Delaney’s house; save for this, nowhere was sign or sound of human life discernible in the lonely settlement. Impenetrable blackness, a mantle of obscurity and silence, the deep brooding silence of the wilderness—these enveloped and overspread all.

Then from the Plains Cree camp far down at the foot of the lake, the muffled note of an Indian drum stabbed like a bullet.

I was strangely affected. There was something sinister, foreboding, in that reverberant boom. I remembered my call a few evenings before at the big dancing lodge on the creek and the suppressed excitement of which I had been the conscious though uncomprehending witness. I had heard the war chief speaking with subdued passion in his soft, vibrant tones, had seen the smothered fire in his sultry, impelling eyes, and I recalled the presage of approaching disaster borne in upon me then. And now as I listened to the throb of the drum I saw it all again: Wandering Spirit speaking and the naked, bronzed warriors with bated breath, their black eyes ashine, hanging in the intervals of the war dance on his burning words. The little settlement might sleep; in Big Bear’s camp few slumbered on this pregnant April night.

I recovered myself with a start. What was I dreaming about? I was a fool, as Quinn had said. Weren’t the Indians friendly? Hadn’t they shown it that day? We, too, had been friendly; there was no reason on earth why their attitude [39] toward us should change. Why should I distrust their professions of good will—feel alarm, this presentiment of evil? I would do so no longer. I was done with forebodings.

But, suddenly—once more—the drum! There had come a lull in the measured beat. Now it had begun again. And immediately I was assailed afresh, and even more rigorously by my mad misgivings. It was one thing, I found, to dismiss one’s worries and another to be quit of them. I knew then that so long as I was aware of the throb of the drum my gloomy premonitions would persist.

If only we had guessed the depths of impending woe that ominous drumbeat portended! If . . ! It might not have been too late; we might still perhaps have stolen out—escaped to the comparative security of Fort Pitt. But—we did not know.

I felt my way in the dark up to my room at the post on the old trading company and tumbled into bed. Big Bear and his tale of the spring of blood came to me. At last I slept, with the steady stroke of the distant drum in my ears and upon my spirit like a pall the prescience of dreadful things close at hand which I was powerless either to mitigate or avert.

Big Bear, as I learned from him long afterward, went straight to his lodge when he returned to camp and went to sleep, for he was tired. Imasees, Wandering Spirit and others of the leaders were in secret council. At midnight the war chief gave an order and four of those in the lodge stepped out quietly and vanished in the gloom.

Isadore Mondion was a minor chief of the Wood Crees with a house on the reservation. He had Iroquois blood in his veins. His father as a young man had paddled his canoe from the St. Lawrence to the Saskatchewan, a voyageur in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Mondion was strong, intelligent and fearless and a friend of the whites. He did not care for these councils of Big Bear’s band; no good was to be expected from them, he thought.

Soon after midnight the door of his house opened and four of Big Bear’s warriors filed silently in. They seated themselves on the floor, and Mondion rose and extended the usual Indian hospitalities. He blew the dull coals in the mud chimney into a blaze and hung the copper pail over it for tea.

“The night is dark,” he said. The visitors nodded “It is warm.” Yes, it was warm, Little Bear agreed. There was a long pause. “You visit late. For what do you come to see me?”

Bare Neck spoke. “Wandering Spirit sent us. You are not a true Cree. Already the police have gone. He does not wish the other whites to leave. He does not trust you.”

Mondion’s eyes flashed. “Wandering Spirit is wise; also he is very brave, and he must think his followers very brave, too, that he sends four to guard a single man!”

Little Bear lowered his rifle threateningly. Mondion struck it up. They clinched and rocked back and forth across the room, until they went down, Little Bear under. The others drew knives and threw themselves on Mondion. They dragged him away and bound him. Not until near daylight did they release him.

Meanwhile Wandering Spirit had not slept. Spies lay about the agent’s house. It was still dark at four o’clock when Imasees and Chaquapocase entered noiselessly through a window and crept upstairs to Quinn’s room. His wife was awake and sprang between the would-be assassins and her husband. Lone Man and Sitting Horse, her brother, flung into the room and confronted the others, guns in their hands.

“Dogs!” cried Lone Man. “Is not his wife a Cree woman and my niece? Let him alone!”

They departed, scowling. “Wandering Spirit will deal with you,” muttered Imasees.

Lone Man was brave and influential, a son-in-law of Big Bear.

“Who is Wandering Spirit,” he sneered. “Tell him Kapayagwan Napaowit protects Kapwatamut!” They remained in the agent’s room. Soon daylight began to filter through the windows. Wandering Spirit forced the front door and entered the office. He took down the three guns hanging there.

“Kapwatamut!” he called. “Come down!”

“Do not go, Kapwatamut!” Lone Man urged. “We will stay and defend you.”

Quinn laughed mirthlessly. “It is useless,” he said. “And [42] never will they be able to say Kapwatamut was afraid to face them!”

He reached the foot of the stairs to find himself surrounded. Wandering Spirit placed a hand on his shoulder. “You are my prisoner,” said the war chief.

I was sleeping soundly in my room at the Hudson’s Bay post. I awoke with a start. A hand, clutching my shoulder, was shaking me roughly. It was just sunrise. I sat up. Walking Horse, a Wood Cree employed about the post, stood beside the bed. His eyes were ablaze with excitement.

“Waniska! Get up!” he cried in Cree. “I think it will be ‘bad’ to-day!”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“They’ve taken the horses from the government stables, already,” he replied. “They say, the half-breeds, but I believe it is Big Bear’s men.”

I needed no further urging. I dressed quickly and went down stairs.

Immediately, Imasees entered, followed by twenty of the younger bucks. Their faces were daubed with vermilion and they carried rifles. Usually, the chief’s son greeted me with some pleasantry, but there was nothing of friendliness on his unsmiling features this morning. He stopped in front of me.

“Have you any ammunition?” he asked curtly.

I thought I was fortunate to be able to tell him that I had.

“Well, we want it.”

He knew the regulations as well as I did. “Where is your order from the agent? You can’t get it without that.”

He leaned forward, his face close to mine. “This is no time for idle talk! If you don’t give it to us, we’ll break the shop open and take it.”

My bluff had not worked. “Oh, if that’s how you put it, I’ll open the shop. If you’re bound to have it I can’t prevent you. I don’t want the lock broken.”

Opening the shop, I called my friend, Yellow Bear, behind the counter. “Hand that keg out,” I told him. “I won’t touch it.”

I had, as has been seen, sent the bulk of the powder to Pitt with the police. They divided what I had kept—perhaps two pounds—among them. Miserable Man leaped over the counter, elbowed me roughly aside and gathered up the scattered bullets on the floor. Others reached across the counter and helped themselves to the long butcher-knives on the shelves, and files with which they began to sharpen them. Big Bear pushed his way in.

“Don’t touch anything in here without leave!” he commanded sternly. “Ask him for it,” indicating me with a wave of his hand. He left the shop again.

Yellow Bear stepped out among them. The old man scowled at the young bucks, shouldering them toward the door. “You have got what you wanted. Neeuk! Go!”

He closed the door and stepped back behind the counter. He picked up a muskrat spear. “I’ll take this,” he said. “I might want to use it, I have no gun.”

Big Bear’s men had already secured all our weapons.