* A Distributed Proofreaders Canada eBook *

This eBook is made available at no cost and with very few restrictions. These restrictions apply only if (1) you make a change in the eBook (other than alteration for different display devices), or (2) you are making commercial use of the eBook. If either of these conditions applies, please check with an FP administrator before proceeding.

This work is in the Canadian public domain, but may be under copyright in some countries. If you live outside Canada, check your country's copyright laws. If the book is under copyright in your country, do not download or redistribute this file.

Title: Montrose

Date of first publication: 1929

Author: John Buchan (1875-1940)

Date first posted: April 2 2012

Date last updated: April 2 2012

Faded Page eBook #20120402

This eBook was produced by: David T. Jones, Ross Cooling, Al Haines & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

In September 1913 I published a short sketch of Montrose, which dealt chiefly with his campaigns. The book went out of print very soon, and it was not reissued, because I cherished the hope of making it the basis of a larger work, in which the background of seventeenth-century politics and religion should be more fully portrayed. I also felt that many of the judgments in the sketch were exaggerated and hasty. During the last fifteen years I have been collecting material for the understanding of a career which must rank among the marvels of our history, and of a mind and character which seem to me in a high degree worthy of the attention of the modern reader. The manuscript sources have already been diligently explored by others, and I have been unable to glean from them much that is new; but I have attempted to supplement them by a study of the voluminous pamphlet literature of the time. My aim has been to present a great figure in its appropriate setting. In a domain, where the dust of controversy has not yet been laid, I cannot hope to find for my views universal acceptance, but they have not been reached without an earnest attempt to discover the truth. J. B.

| Introductory: The Early Seventeenth Century | 15 |

| I. Youth | 33 |

| II. The Strife in Scotland | 44 |

| III. The First Covenant Wars | 77 |

| IV. Montrose and Argyll | 106 |

| V. The Rubicon | 136 |

| VI. The Curtain Rises | 167 |

| VII. Tippermuir | 178 |

| VIII. Aberdeen and Fyvie | 198 |

| IX. Inverlochy | 213 |

| X. The Retreat from Dundee | 229 |

| XI. Auldearn and Alford | 240 |

| XII. Kilsyth | 261 |

| XIII. The War on the Border | 273 |

| XIV. After Philiphaugh | 291 |

| XV. The Years of Exile | 317 |

| XVI. The Last Campaign | 347 |

| XVII. The Curtain Falls | 361 |

| XVIII. "A Candidate for Immortality" | 382 |

| Appendix: Montrose on "Sovereign Power" | 397 |

| Index | 409 |

Montrose (after the portrait painted by Honthorst for the Queen of Bohemia, in the Collection of the Earl of Dalhousie)

Frontispiece

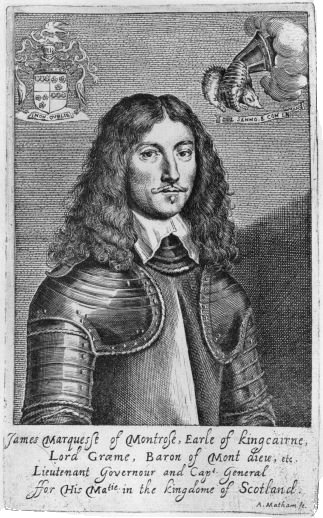

Montrose (from an engraving by A. Matham, forming the frontispiece to the 1647 Hague translation of Wishart)

facing page 274

The cross and motto on the cover of the book are copied from the Declaration issued by Montrose at the beginning of his campaign in 1644, preserved among the papers of the Napier family.

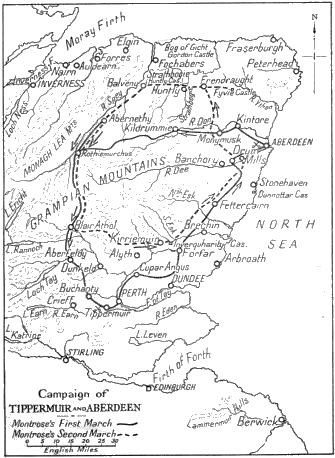

| 1. Campaign of Tippermuir and Aberdeen | 190 |

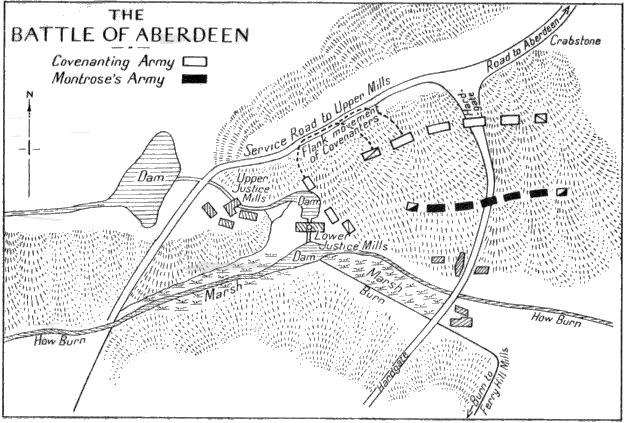

| 2. Battle of Aberdeen | 200 |

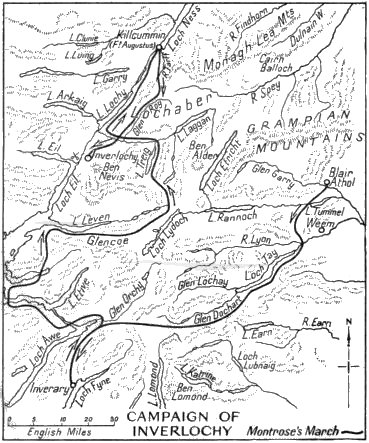

| 3. Campaign of Inverlochy | 218 |

| 4. Campaign of Dundee and Auldearn | 238 |

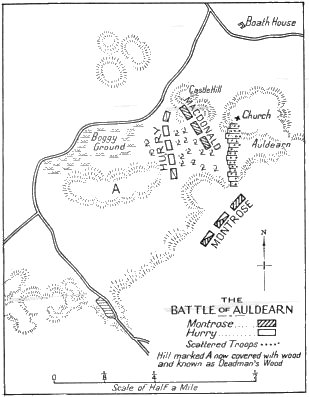

| 5. Battle of Auldearn | 246 |

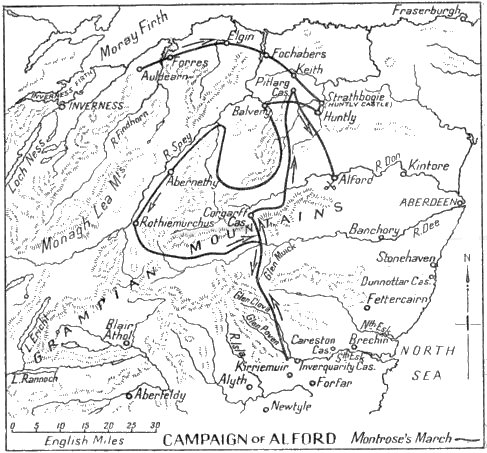

| 6. Campaign of Alford | 252 |

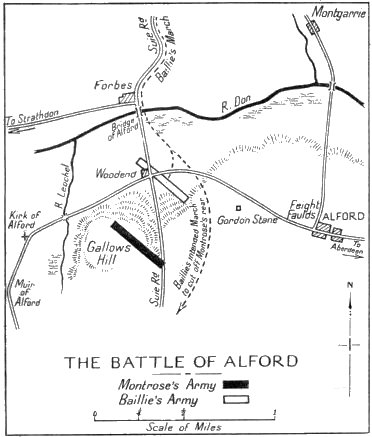

| 7. Battle of Alford | 256 |

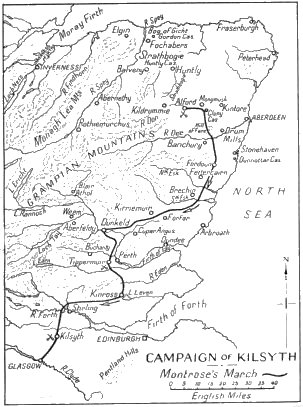

| 8. Campaign of Kilsyth | 262 |

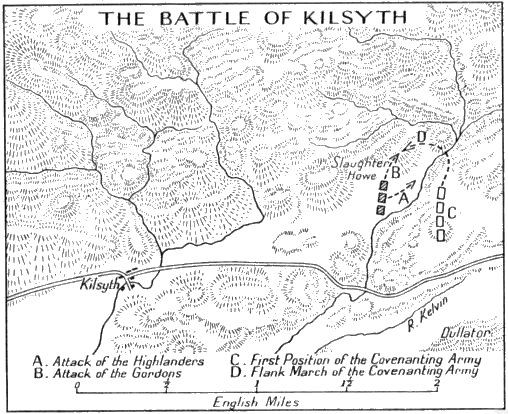

| 9. Battle of Kilsyth | 270 |

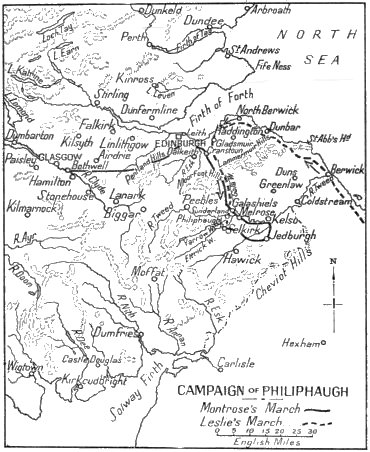

| 10. Campaign of Philiphaugh | 282 |

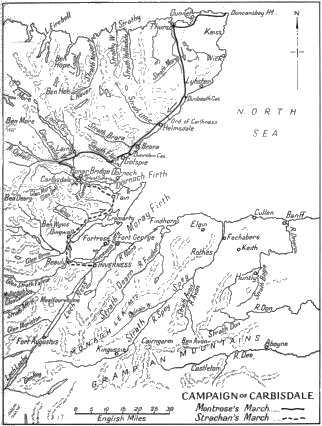

| 11. Campaign of Carbisdale | 352 |

| A. P. S. | Acts of the Parliaments of Scotland. 12 vols., 1834-75. |

| Army of the Covenant | Papers relating to the Army of the Solemn League and Covenant (1643-47). 2 vols. (S. H. S.), 1917. |

| Baillie | Letters and Journals of the Rev. Robert Baillie. 3 vols., 1841. |

| Balfour | Historical Works (Annales) of Sir James Balfour. 4 vols., 1824-25. |

| Burnet, Mem. of the Hamiltons | The Memoirs of James and William, Dukes of Hamilton, by Gilbert Burnet, 1677. |

| Calderwood | History of the Kirk of Scotland (1524-1625), by David Calderwood (Wodrow Society). 8 vols., 1842-59. |

| Cal S. P., Dom. | Calendar of State Papers, Domestic. |

| Clanranald MSS. | The narrative of Alasdair Macdonald's campaign, by a shanachie of Clanranald in the "Black Book of Clanranald." It is translated in Cameron's Reliquiæ Celticæ, II., 138-209 (Inverness, 1894), and the Gaelic text has been edited by Joseph Lloyd, with an historical introduction by Professor Eoin McNeill, in Alasdair Mac Colla (Dublin, 1914). |

| Clarendon, Hist. | History of the Rebellion, by Edward, Earl of Clarendon (ed. Macray), 1888. |

| Firth | Cromwell's Army, by Sir C. H. Firth, 1902. |

| Forbes Leith | Memoirs of Scottish Catholics during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, by William Forbes Leith, S.J. 2 vols., 1909. |

| Gardiner | History of England, by S. R. Gardiner. 10 vols., 1886. |

| Gardiner, Civil War | History of the Great Civil War, by S. R. Gardiner. 4 vols., 1910. |

| Gordon of Rothiemay | History of Scots Affairs, by James Gordon (Spalding Club). 3 vols., 1841. |

| Gordon of Ruthven | Britane's Distemper, by Patrick Gordon (Spalding Club), 1844. |

| Gordon of Sallagh | Continuation (by Gilbert Gordon of Sallagh) of A History of the Earldom of Sutherland, by Sir Robert Gordon of Gordonstoun, 1813. |

| Guthry | Memoirs of Henry Guthry, Bishop of Dunkeld. 2nd edition, Glasgow, 1747. |

| Gwynne | Military Memoirs of the Great Civil War, by John Gwynne (ed. Sir W. Scott), 1822. |

| Hist. MSS. Comm. | Reports of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. |

| Lang | History of Scotland, by Andrew Lang. 4 vols., 1900-6. |

| M. & S. | Editorial matter in edition of Wishart by Murdoch and Simpson. |

| Mem. of M. | Memorials of Montrose and his Times, ed. by Mark Napier (Maitland Club). 2 vols., 1848-50. |

| Monteith | The History of the Troubles of Great Britain, etc., by Robert Monteith of Salmonet. Eng. trans., 1738. The French original, Histoire des Troubles de la Grande Bretagne, was published in Paris in 1661. |

| Napier | Memoirs of the Marquis of Montrose, by Mark Napier. 2 vols., 1856. |

| P.C.R. | Register of the Privy Council of Scotland. 2nd series, 8 vols., 1899-1908. |

| Rothes | Relation of Proceedings concerning the Affairs of the Kirk of Scotland, by John, Earl of Rothes (Bannatyne Club), 1830. |

| Row | History of the Kirk of Scotland (1558-1637), by John Row (Wodrow Society), 1842. |

| Rushworth | Historical Collections of Private Passages of State, etc., by John Rushworth. 8 vols., London, 1721. |

| S.H.R. | Scottish Historical Review. |

| Spalding | The History of the Troubles and Memorable Transactions in Scotland and England (1624-45), by John Spalding (Bannatyne Club). 2 vols., 1828. |

| Spottiswoode | History of the Church and State of Scotland (203-1625), by John Spottiswoode (Spottiswoode Society). 3 vols., 1851. |

| Wardlaw MS. | Chronicles of the Frasers: the Wardlaw MS., by James Fraser (S. H. S.), 1905. |

| Wariston | Diary of Sir Archibald Johnston of Wariston, Vol. I., 1632-39 (S. H. S.), 1911; Vol. II., 1650-54, 1919. |

| Wigton Papers | "Documents from the Archives of the Earls of Wigton, 1520-1650," in Miscellany of the Maitland Club, Vol. II., 1840. |

| Wishart | The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose, by the Rev. George Wishart, edited by Alexander Murdoch and H. F. Morland Simpson, 1893. [Wishart's narrative is referred to by its chapters, and when a page is indicated the reference is to the Latin text in this edition.] |

In a famous letter Keats has expounded life under the similitude of Chambers. There is first the Thoughtless Chamber, when man lives only for sensation; then comes the Chamber of Maiden Thought, when he consciously rejoices in the world of sense, and from this happy illumination acquires insight into the human heart; thence open many doors—"but all dark, all leading to dark passages." The simile applies not only to individual experience, but to the corporate life of peoples. There come epochs when a nation seems to move from the sun into the twilight, when the free ardour of youth is crippled by hesitations, when the eyes turn inward and instinct gives place to questioning.

Such a period commonly follows an age of confidence and exuberant creation. We can see the shadows beginning to lengthen in the early years of Elizabeth's successor, and they do not lift till the garish dawn of the Restoration. It is dangerous to generalize about an epoch, but the first half of the seventeenth century has a character so distinct that it is permissible to separate certain elements in its intellectual atmosphere, which affected the minds of all who dwelt in it, whatever their creeds or parties. Whether we study it in the record of its campaigns and parliaments, or in the careers of its protagonists, or in the books of its great writers, three facts are patent in contrast with its predecessor.

"Is not this world a catholic kind of place?" Carlyle has [16]written. "The Puritan gospel and Shakespeare's plays: such a pair of facts I have rarely seen saved out of one chimerical generation." The greatness of the Elizabethan age was that it was catholic; that is, a number of potent, and usually conflicting, forces were held for a brief season in equilibrium. The Reformation had broken certain seals of thought, but it had not destroyed the integrity of the Church. The Middle Ages, in the monarchy and in much of the law and custom of the people, co-existed with the new learning and the adventurous temper of the Renaissance. England could conquer strange worlds and yet maintain intact her ancient domestic life. The national mood was one of confidence and ardour, so intent upon present duties and enjoyments that it could permit the latent antagonisms to slumber. But in the first decade of the seventeenth century the mutterings in sleep became a restless awaking. The monarchy, when the great figure of Elizabeth passed, was seen to be a mediæval anomaly, and prerogatives hitherto unchallenged were soon a matter of hot debate. The ecclesiastical compromise which created the Anglican Church found many critics, and even those who accepted the fact were at odds about the theory. Sanctions, which had seemed imperishable, began to tilt and crack. The old world was crumbling, and there was no unanimity about the new.

Following upon this loss of harmony in institutions came a change in the national mood, which may be described, perhaps, as a failure of nerve. The forthright enjoying temper of the Elizabethans had gone; the world was no longer so simple and so spacious; the stage had become full of questioning Hamlets. It is a mood familiar to students of classical antiquity, and may be found in high relief during the first centuries of our era. The weakening of the social fabric, and consequently of the protective power of society, increases the strain on the personality. The hopefulness of youth is succeeded by a sad acquiescence, if not by despondency: the eye looks inward; the soul is disillusioned with the world, and seeks refuge elsewhere. It is the preparatio evangelica, for it [17]turns the mind to God. In such a mood religion comes to birth, for the worldliness of youth rejoicing to run its course is exchanged for the spirituality of those who find here no continuing city. Life seems no longer a thing to be shaped by man's endeavour, and in every creed, from the predestination of the Calvinist to the mystical Platonism of the scholar, it is conceived as a puppet-play moved by the hand of Omnipotence. Metaphysic has broken into a secure world, and with it have come a sense of sin, a constant dwelling upon death, a haunting consciousness of eternity.

Something of this temper soon became dominant in the land. Robust spirits might reject it and recover the pagan standpoint; wise men might struggle through it to certainty and peace; but the shadow of it was universal, even in the defiance of the pagan. There was everywhere a quickening and intensifying of certain spiritual emotions, a sense of man's littleness and dependence upon the unseen, a movement away from humanism towards mysticism, a clouding of horizons which had once been so bright and clear. The congregations which listened to Donne's analysis of sin and his pictures of the "various and vagabond heart of the sinner" thronged to St. Paul's because the preacher was in tune with their own thoughts. Death was so much with them that they found comfort in envisaging its terrors. There was satisfaction in the belittling of life: "We have a winding-sheet in our mother's womb, which groweth with us from our conception, and we come into the world wound up in that winding-sheet, for we come to seek a grave."[1] The unthinkableness of eternity hag-rode their imagination. "Methusalem with all his hundreds of years was but a mushroom of a night's growth to this Day, and all the four Monarchies with all their thousands of years, and all the powerful Kings and all the beautiful Queens of this world, were but as a bed of flowers, some gathered at six, some at seven, some at eight, all in one morning, in respect of this Day."[2]

[18]A consequence of such a mood was that men believed, as in the days of St. Cyprian, that the youth of the world had gone, and that they were living in its old age. The new science, the new astronomy, assisted the mood by breaking down the old comfortable, concentric universe. "There prevailed in his (Milton's) time an opinion that the world was in its decay, and that we have had the misfortune to be produced in the decrepitude of Nature. It was suspected that the whole creation languished, that neither trees nor animals had the height or bulk of their predecessors, and that everything was daily sinking by gradual diminution."[3] We find the belief in Raleigh: "The long day of mankind draweth fast towards an evening, and the world's tragedy and time are near at an end."[4] "Think not thy time short in this world," wrote Sir Thomas Browne, "since the world itself is not long."[5] It is everywhere in the sermons of the divines. Man is "an aged child, a grey-headed infant," and but a ghost of his own youth.[6] "As the world is the whole frame of the world, God hath put into it a reproof, a rebuke, lest it should seem eternal, which is a sensible decay and age in the whole frame of the world and every piece thereof. The seasons of the year irregular and distempered; the sun fainter and languishing; men less in stature and shorter lived. No addition, but only every year new sorts, new species of worms and flies and sicknesses, which argue more and more putrefaction of which they are engendered."[7] "This is the world's old age; it is declining; albeit it seems a fine and beautiful thing in the eyes of them that know no better, and unto those who are of yesterday and know nothing it looks as if it had been created yesterday, yet the truth is, and a believer knows, it is near the grave."[8] "The world's span-length of time is drawn now to less than half an inch, and to the point of the evening of the day of th[19]is old grey-haired world."[9] The result of such a belief was to cheapen the value of human endeavour, to show human greatness as trivial against the vastness of eternity. "Jezebel's dust is not amber, nor Goliah's dust terra sigillata, medicinal; nor does the serpent, whose meat they are both, find any better value in Dives dust than in Lazarus."[10] There was but one paramount duty in life, to save the soul. "These are the two great works which we are to do in this world: first to know that this world is not our home, and then to provide us another home whilst we are in this world."[11] "Build your nest upon no tree here," Samuel Rutherford wrote to Lady Kenmure, "for ye see God hath sold the forest to death." These are more than the commonplaces of theology; they are the expression of a temper which, by the year 1630, had become a background to thought, an atmosphere which insensibly coloured every man's outlook.[12]

In an age of uncertainty and change there is inevitably a craving for definition and discipline. Even if this or that law is dubious, Law itself is regarded as more than ever essential; in Hooker's famous panegyric her seat is in the bosom of God, her voice the harmony of the world, and she is the mother of all peace and joy. To live at all, man must make rules and keep them, and in the prevalent flux he hankers after rigidity. The more doubtful the political outlook the fiercer will be the dogmas which men create and contend for; the more the foundations of the Church are shaken the more high-flying and arbitrary will be the conflicting creeds. It is an old trait of human nature, when in the mist, to be very sure about its road. In such an era a religious faith tends to become a complete philosophy of life, governing also the minutest details of the sec[20]ular world. Man cries for guidance and authority, and if he rejects one sanction he will invent others more compelling than the old. Having shaken himself loose from history, he tends to an abstract idealism. The English polity had been built up piecemeal by many compromises, but its seventeenth-century critics were apt to forget this, and to devise, like Milton, a brand-new symmetrical structure, unrelated to the past.[13] But Milton had the supreme merit that he always believed in the free and rational soul of man. "He who wisely would restrain the reasonable soul of man within due bounds, must first himself know perfectly how far the territory and dominion extends of just and honest liberty. As little must he offer to bind that which God hath loosened as to loosen that which He hath bound. The ignorance and mistake of this high point hath heaped up one huge half of all the misery that hath been since Adam." The human reason was not commonly valued so high by Milton's contemporaries, and they readily bent themselves before authority—of king or parliament, of bishop, Bible or congregation, or of personal revelation. Differences, which should have been discretionary, were elevated into matters of essential principle, and men were ready to stake body and soul on the finest points of dogma in Church and State.

Happily these troubles of the spirit, so far as England was concerned, befell in a society nicely integrated and fundamentally stable. Men of quick conscience and fine intelligence, who are the shaping spirits in any era, felt their impact, but there were in the land strong stabilizing forces which were for long untouched by them, and which made it certain that change would come by slow degrees. There was not, as on the continent of Europe, a gulf fixed between the nobility and the commonalty; the nobles were no more than the topmost class of a great body of gentry which in the lower ranges came very near to the yeomanry, and embraced what we know to-day as the middle and[21] professional classes. Even at the summit, the grandees of Plantagenet and Tudor origin found themselves compelled to mix with the new creations of James I. A family of Norman descent would apprentice a younger son to a trade, and marry a daughter to some new City knight or young lawyer from the Temple. Boys of ancient houses sat side by side on the grammar-school benches with the sons of farmers and tradesmen. The land was organized locally for defence and administration; an unpaid magistracy enforced the king's mandates and administered the new poor law; the ordinary citizen was the only soldier, the mediæval levy had not yet disappeared, and on the Marches manorial tenants armed with broadswords still met the judges of assize. There was little rigidity among classes, but the intensity of provincial feeling gave immense power to those local leaders who had a long tradition of popularity, so that the Lancashire gentry were accustomed to wear the Stanley livery. Shire, parish, and town were living organisms, managing their affairs with little outside interference, and to buttress their honest particularism there was a mass of hoar-ancient custom and tradition which gave a man of Gloucestershire a different outlook from a man of Devon or Kent. England still stood in the old ways, and in her affection for them lay a vast latent conservative power. But with this conservatism was joined a high measure of independence. The progress of enclosures was bringing the yeoman and the tenant-farmer into greater importance, and if each locality had its special patriotism, so had each class its own stubborn loyalties. So far as we can judge, it was on the whole a comfortable society, full of ancestral jollities, and secure, for in most parts of England a century had elapsed since the tramp of armies had echoed in their fields.

North of the Tweed the case was different. Scotland had for centuries been emptied from vessel to vessel, and civil war was in the memories of living men. In the Highlands the clan system still held together a primitive society, but its Border variant had[22] broken down, and elsewhere no settled order of life had been developed. The Scottish nobles had not laid aside their ancient turbulence; whereas in England the duel was coming into fashion (a step towards civilization), they still held by bravos and the "killing affray."[14] All classes were miserably poor; the gentry lived squalidly in their little stone towers, the peasant was half-starved and half-clad, and rural life had few of the English amenities. The land was strewn with the relics of mediævalism, and amid this lumber the spirit of the Knoxian Reformation burned furiously, destroying much that was ill and not a little that was good. In a later chapter we shall consider more closely the condition of Scotland; here it is sufficient to note that the land was far readier for violent change than its southern neighbour. Its conservatism was a thing of private sentiment and passion rather than of fidelity to proved institutions; its history had given it a noble patriotism, but few things to cherish beyond a savage independence, and the cataclysmic breach with the ancient Church had predisposed it to other breaches. At the same time the Union of the Crowns had brought it into close relations with England, its nobility frequented the court, its civil and ecclesiastical policies were affected by Westminster. No overt act, no spiritual mood of England could be without its reactions in the north, and a flame which burned slowly amid the lush meadows and green hedgerows might run like wildfire among the dry heather.

An era of unrest produces a thousand types, but in the long run they range themselves in two parties, for human nature—especially English human nature—tends always to a dualism. It is not easy to find a definition for either Cavalier or Puritan which shall embrace on the one hand Suckling and Traherne, Laud and Clarendon, Rupert and Falkland: on the other Hampden and Barebone, Bunyan and Milton, Ireton and Lilburne. From the one party we may exclude the mere roysterers—Milton's "sons of Belial, flown with insolence and wine"—and from the other th[23]e hypocrites and the crack-brains; every great cause has its unworthy camp-followers. The division was not a social one, for the Puritans had many of the old nobility and some of the best of the country gentry in their ranks; and the Cavaliers had the bulk of the peasantry and a share of the trading and professional classes. The two factors in the situation were the crumbling of old things and the need of substitutes, the questioning and the demand for certainty; the problem was how to define the fundamentals, and where to find authority. Men of the same party answered it in different and often inconsistent ways.

The stream of the Cavalier temperament was fed by many distant springs. There was the punctilio of honour, the devotion to a master, which made royalists of simple and chivalrous souls: men like Hopton and Capel, Sunderland and Sir Bevil Grenville; men like Sir Edmund Verney, the knight marshal, from whose dying hand the standard dropped at Edgehill, though his creed was not that of the king. There were the lovers of Old England like Clarendon, its old Church, its folk religion, "its old good manners, its old good humour, and its old good nature"—things like to be destroyed by rash hands which could only offer a drab alternative. There were the believers in a central authority, and in the domain of law as against anarchy—liberal thinkers for the most part, and zealous reformers, who stood as firmly as Milton for the freedom of the human spirit, but resisted an iconoclasm which they held to be the path to servitude. Such were Falkland—who has given true conservatism its motto: "When it is not necessary to change, it is necessary not to change"—and Sidney Godolphin, who, like his friend, fell early on the battlefield.[15] There were the opportunists as against the dogmatists, the men who held with Donne that truth is not found by the straight road of an easy revelation, but must be sought by a spiral course, and[24] that, as Cosin put it, "faith is not on this side knowledge, but beyond it." There were the scholars, full of the classical Renaissance; and the Platonists, who were not content to make the Bible the one source of truth or to condemn as carnal what they held to be divine. And there were the poets, who refused to narrow the world which God had made, and, like Herbert and Vaughan and Traherne, found everywhere "bright shoots of everlastingness"; in such men mysticism does not reject humanism, but enfolds and transcends it.

In this medley of types there was infinite room for difference—Laud's theory of church government, for example, was antipathetic to most of the party—but under the pressure of their opponents they found common ground, and a temperament was hardened into a creed. That creed was, shortly, the need of preserving a central authority in the kingship. Men who had hotly criticized Charles's policy, who had no love for Laud and his ways, who had sympathized with Hampden and Eliot, found themselves ranged beside country squires who had few ideas beyond ale and foxes. Just as Oxford's treasures of Renaissance plate were melted down to provide current coin for the troops, so far-reaching doctrines were given a partial and popular statement, and philosophies were reduced to formulas and watchwords. In the Middle Ages treason was held the rankest of crimes, because so little was needed to wreck the brittle mechanism of the State. So now, with change and anarchy in the air, lovers of order stood by the one well-sanctioned existing authority—the king.

In the Puritan party we find less variety of type and a simpler temperament, but here also is diversity. The basis was in the first instance religion.[16] The original Puritan was one who desired to purify the Church from all taint of Romanism, and to the end there were Puritans who remained Churchmen. But[25] presently, as the difficulties of the task became apparent, criticism of liturgical forms and of the extravagances of episcopal power hardened with many into an opposition to all hierarchical church government, and the acceptance of the Presbyterian doctrine of the "priesthood of all believers" and the polity of the reformed churches in France, Switzerland, and Scotland. This ecclesiastical preference was extended into secular affairs, and the Puritan added to his creed a passion for civic freedom. There were also the sectaries who had been persecuted since the early days of Elizabeth, and who were distasteful alike to Anglican and Presbyterian—men who were extreme individualists in church matters, and regarded the congregation as the divinely appointed organism.

Puritanism was neither an ecclesiastical system nor a theological creed. Calvinism, with its doctrine of "exclusive salvation," was, at first, the belief of Anglican and Presbyterian alike, and it remained the prevailing creed of the Puritan party as of the bulk of their opponents—rejected only by Laud's Arminian school, and by sects like the Baptists and the Quakers. The most powerful statement of Puritan theology will be found in Anglican divines like Donne; no Scottish Covenanter ever dwelt more terribly upon original sin, the torments of hell, and the awe of eternity.[17] Nor was the Puritan either a very learned and subtle theologian, or a profound expositor of his own ecclesiastical tastes. When a man of Milton's genius embarks upon doctrinal questions[18] he is "in wandering mazes lost," like the evil spirits in Paradise Lost, who sat on a hill and debated predestination. For wisdom, breadth of knowledge, and logical acumen, no Puritan champion can vie with Hooker, Chillingworth, John Hales, and Jeremy Taylor—few even reach the standard of Laud.[26]

Puritanism was above all things the result of a profound spiritual experience in the Puritan. It is to John Bunyan and George Fox that we must go if we would learn the strength of the faith. The questioning of the epoch resulted for such men in an overwhelming sense of sin and an overpowering consciousness of God; their knowledge, in Cromwell's famous words, was not "literal and speculative, but inward and transforming the mind to it." Unless we realize this primary fact we cannot explain why so many diverse creeds were ultimately conjoined to form one conquering temperament. Inevitably the faith and the practice narrowed and hardened. Sunday, the day on which Calvin played bowls and John Knox gave supper parties, became the Jewish Sabbath, and the Mosaic law in many of its most irrelevant details was incorporated with the Christian creed. Toleration was impossible for men who saw life as a narrow path through a land shaken by the fires of hell; only kindred communions were tolerated, save by those few sects who, from hard experience, had learned a gentler rule. A limited number inclined to a complete separation of Church and State, but the majority desired a purified State, which would be the ally and the servant of the Church. They rejected the world of sense, for there could be no innocency in what had been corrupted by Adam's sin, and their eyes were fixed austerely upon their own souls. The strength of Puritanism lay in its view of the direct relation of God and man; its weakness in the fact that this relation was narrowly and often shallowly construed. The Puritan became, by his severe abstraction, a dangerous element in society and the State, since human institutions are built upon half-truths, opportunisms, and compromises. He was pre-eminently a destructive force, for he was without the historical sense,[19] and sought less to erect and unite than to pull down and separate. Milton's words might be taken as his creed: "By His divorcing command the world first rose out of chaos; nor can be renewed again out of[27] confusion but by the separating of unmeet consorts."[20]

With the Puritans, as with the Cavaliers, many streams from remote wells were in the end canalized into a single channel. The mood of those who accepted the natural world as the gift of God was set against that which saw that world as conceived in sin and shapen in iniquity: the ancient institutions of the realm, which to the mind of the Cavalier should be reformed, but in substance retained, were opposed to a clean page on which men could write what they pleased; the conception of the State as a thing of balances and adjustments was met by a theory of government as an abstract ideal to be determined mainly by the half-understood words of an old book: the free exercise of men's conscience in religion was confronted with a denial of freedom except to those of a certain way of thinking. The truth is that the Puritan was hampered both in civil and ecclesiastical statesmanship by that intense individualism which was also his strength. His creed was not social or readily communicable—

To him, as to Newman in his youth, the world was narrowed to "two, and two only, supreme and luminously self-evident beings"—himself and his Creator.

If we put the contrast thus, it would seem that generosity and enlightenment were predominantly on the side of the Cavaliers. But it must not be forgotten that, owing to the spiritual atmosphere of the age and the tendency in such a conflict to narrower and yet narrower definition, the common creed of Puritanism did not fairly represent the best men in its ranks. Had Hampden and Falkland ever argued on fundamentals they might well have found themselves in substantial agreement. The difference, as the struggle progressed, came to lie far less in creeds than in the moods behind them, and the Puritan mood, solemn under[28] the Almighty's eye, austere, self-centred, unhumorous, unbending, was more formidable and more valuable than their crude apologetics. Its spiritual profundity was as rich a bequest to the future as the saner and sunnier temper of the Cavalier. The difference between the best men of the two parties was a fine one—the exact border-line between the king's prerogative and popular liberties in Church and State; but most great contests in the world's history have been fought on narrow margins. And in practice the narrowness disappeared, and the divergence was glaring. For the Cavalier, with his reasoned doctrine of a central authority based on historical sanctions, had to define that authority as the king, and that king not an ideal monarch, but an actual person then living in Whitehall. The Puritan, who might have dissented reluctantly from the abstract argument, was very ready to differ about Charles.

The conflict which we call the Civil War took place under the shadow which overhung the thought of the first half of the seventeenth century. In that gloom, as we have seen, men were predisposed to define arbitrarily and fly to rigid dogma as to a refuge, for in such a constriction they found peace and strength. Those who maintained the integrity of the spirit, and refused to blindfold their minds, cloistered themselves, or, if they ventured on a life of action, were as a rule Verneys or Falklands, heartsick, distracted, "ingeminating Peace." The effective protagonists were those Cavaliers whose loyalty knew no doubts, and those Puritans who were strong in the confidence of their Lord.

It is the purpose of this book to trace the career of one whose campaigning ground was Scotland, where antagonisms were fiercer and blinder than in the south; one who did not drug his soul with easy loyalties, but faced the problem of his times unflinchingly, and reached conclusions which had to wait for nearly two hundred years till they could be restated with some hope of acceptance; one who, nevertheless, had that[29] single-hearted gift for deeds which usually belongs to the man whose vigour is not impaired by thought. Montrose has been called by Carlyle the noblest of the Cavaliers, yet clearly he was no ordinary Cavalier; for at the start he was a Covenanter and in rebellion against the king—rebellion of which he never saw reason to repent, and to his dying day he remained a convinced Presbyterian.

George Herbert.

The Highland Line in the Scottish mainland, though variously determined at times by political needs, has been clearly fixed by nature. The main battlement of the hills runs with a north-easterly slant from Argyll through the Lennox, and then turns northward so as to enclose the wide carselands of Tay. Beyond lie the tangled wildernesses stretching with scarcely a break to Cape Wrath; east and south are the Lowlands proper—on the east around Don and Dee and the Forfarshire Esks: on the south around Forth and Clyde, and embracing the hills of Tweed and Galloway. Scotland had thus two Borderlands—the famous line of march with England, and the line, historically less notable but geographically clearer, which separated plain from hill, family from clan, and for centuries some semblance of civilization from its stark opposite. The northern Border may be defined in its more essential part as the southern portion of Dumbarton and Lennox, the shire of Stirling, and the haughs of the lower Tay. There for centuries the Lowlander looked out from his towns and castles to the blue mountains where lived his ancestral foes. Dwelling on a frontier makes a hardy race, and from this northern Border came famous men and sounding deeds. Drummonds, Murrays, Erskines, and Grahams[34] were its chief families, but most notably the last. What the name of Scott was in the glens of Teviot, the name of Graham was in the valleys of Forth and Earn. Since the thirteenth century they had been the unofficial wardens of the northern marches.

The ancient nobility of Scotland does not show well on the page of history. The records of the great earldoms—Angus, Mar, Moray, Buchan—tell too often an unedifying tale of blood and treason, and, after the day of the Good Lord James, St. Bride of Douglas might have wept for her children. But the family of Graham kept tolerably clean hands, and played an honourable part in the national history. Sir John the Graham was the trusted friend of Wallace, and fell gloriously at Falkirk. His successors fought in the later wars of independence, thrice intermarried with the royal blood, and gave Scotland her first primate. In 1451 the family attained the peerage. The third Lord Graham was made Earl of Montrose, when the short-lived Lindsay dukedom lapsed, and the new earl died with his king in the steel circle at Flodden. A successor fell at Pinkie; another became Chancellor and then Viceroy of Scotland when James the Sixth mounted the English throne. The Viceroy's son, the fourth earl, apart from a famous brawl in the High Street of Edinburgh, lived the quiet life of a county laird till, shortly before his death he, too, was appointed Chancellor. He was a noted sportsman, a great golfer, and a devotee of tobacco. His wife was Lady Margaret Ruthven, a daughter of the tragically-fated house of Gowrie, who bore him six children, and died when her only son was in his sixth year. The family was reasonably rich as the times went, for the home-keeping Earl John had conserved his estate. They owned broad lands in Stirling, Perth, and Angus, and wielded the influence which the chief of a house possesses over its numerous cadets. They had three principal dwellings—the tower of Mugdock in Strathblane; the fine castle of Kincardine in Perthshire, where the Ochils slope to the Earn; and the house of Old Montrose, which Robert[35] Bruce had given to a Graham as the price of Cardross on Clyde.

James Graham, the only son of the fourth earl and Margaret Ruthven, was born in the year 1612, probably in the month of October[21]—according to tradition, in the town of Montrose. The piety of opponents has surrounded his birth with omens; his mother is said, with the hereditary Ruthven love of necromancy, to have consulted witches, and his father to have observed to a neighbour that this child would trouble all Scotland.[22] Like Cromwell, he was the only boy in a family of girls. Of his five sisters, the two eldest were married young—Lilias to Sir John Colquhoun of Luss, and Margaret to a wise man of forty, the first Lord Napier of Merchiston. Their houses were open to him when he tired of catching trout in the little water of Ruthven, or wearing out horseshoes on the Ochils, an occupation to which the extant bills of the Aberuthven blacksmith testify. There was much in the way of adventure to be had at Rossdhu, Lady Lilias's new dwelling, and there the boy may have learned, from practising on the roebuck and wild goats of Lochlomondside, the skill which made him in after years a noted marksman.

At the age of twelve Lord Graham was entrusted to a certain William Forrett, master of arts, to be prepared for the college of Glasgow. Thither he journeyed with a valet, two pages in scarlet, a quantity of linen and plate, a selection from his father's library, and his favourite white pony. He lived in the house of Sir George Elphinstone of Blythswood, the Lord Justice Clerk; it stood near the Townhead, and may have been one of the old manses of the canons of the Cathedral. The avenues to learning must have been gently graded, for he retained a happy memory o[36]f those Glasgow days and of Master Forrett, who in later years became the tutor of his sons. He seems to have read in Xenophon and Seneca, and an English translation of Tasso; but his favourite book, then and long afterwards, was Raleigh's History of the World, the splendid folio of the first edition.

In the second year of Glasgow study the old earl died, and Lord Graham posted back to Kincardine, arriving two days before the end. Thither came the whole race of Grahams for the funeral ceremonies, which lasted the better part of three weeks. Prodigious quantities of meat and drink were consumed, for each neighbour and kinsman brought his contribution in kind—partridges and plovers from Lord Stormont, moorfowl from Lawers, a great hind from Glenorchy—the details are still extant, with the values of woodcock and wild geese, capercailzie and ptarmigan, meticulously set down. If such mourning had its drawbacks, at any rate it introduced the new head of the family to those of his name and race. He did not return to Glasgow (though five years later he showed his affection for the place by making a donation to the building of the new college library), and presently was entered at St. Salvator's College, St. Andrews, of which one of his forbears had been a founder. Master Forrett brought his possessions from Glasgow, and the laird of Inchbrakie bestowed these valuable items, the books, in a proper cabinet.

We have ample documents to illustrate his St. Andrews' days.[23] The university, the oldest and then the most famous in Scotland, had among its alumni in the first half of the seventeenth century men so diverse as Montrose and Argyll and Rothes, Mr. Donald Cargill and Sir George Mackenzie. His secretary was a Mr. John Lambie, and Mr. Lambie's accounts reveal the academic life in those days of a gentleman-commoner. In sport his tastes were catholic. He golfed, like James Melville a century before, and paid five shillings Scots for each golf ball. His rooms at St. Salvator's were[37] hung round with bows, and in his second year he won the silver medal for archery, which to the end of his college course he held against all comers. Argyll, who was some years his senior, had carried off the same trophy. He was an admirable horseman, and he seems to have hunted regularly; it is recorded in the accounts that after a day with hounds his horse was given a pint of ale. He was fond of hawking, and he went regularly to Cupar races, handing over, according to the excellent statute of 1621, his winnings beyond one hundred marks to the local kirk session for the relief of the poor. His chief friends of his own order seem to have been Wigton, Lindsay of the Byres, Kinghorn, Sinclair, Sutherland, and Colville, and he varied his residence at St. Andrews with visits to his brother-in-law (the hills of Rossdhu, complains his steward, wore the boots off his feet), the cadet gentry of his name, and Cumbernauld, Glamis, Kinnaird, Balcarres, and the other country-houses of his friends. In October 1628 he gave a great house-warming at Kincardine, which lasted for three days. In the March following he visited Edinburgh, where he appeared in gilt spurs and a new sword, and was lent the Chancellor's carriage. The picture which has come down to us of the undergraduate is that of a boy happy and well-dowered, popular with all, eager to squeeze the juice from the many fruits of life. Nor was he above youthful disasters. When his sister Dorothea married Sir James Rollo, there was huge feasting in Edinburgh and Fife, and the young earl returned to college only to fall sick. Two doctors were summoned, who charged enormous fees, and prescribed a rest cure—strict diet, and no amusements but cards and chess. The barber shore away his long brown curls, and "James Pett's dochter" attended to the invalid's food. The régime seems high feeding for what was probably an attack of indigestion—trout, pigeons, capons, "drapped eggs," calf's-foot jelly, grouse (out of season), washed down by "liquorice, whey, possets, aleberry, and claret."[38]

From the accounts preserved we can trace something of his progress in learning. He began to study Greek, and continued his reading in the Latin classics, his favourites now being Cæsar and Lucan, in his copies of which he made notes. He can never have been an exact scholar, and it is probable that the wide knowledge of classical literature which he showed later was largely acquired from translations. For it was the day of great translators, and at St. Andrews he had at his service North's Plutarch, Philemon Holland's Livy and Suetonius, Thomas Heywood's Sallust, and the Tacitus of Sir Henry Savile and Richard Grenewey. Nor did he neglect romances, and he made his first essays in poetry. To this stage may belong the lines ascribed to him by family tradition, in which the ambitious boy writes his own version of a popular contemporary conceit; but he does not end, like the other versions, on a note of pious quietism:

He had a touch of the bibliophile, for he had his copies of Buchanan and Barclay's Argenis specially bound. To poor authors he was a modest Mæcenas. The accounts show a payment of fifty-eight shillings Scots to "ane Hungarian poet, who made some verses to my lord." He subscribed for the travels of the fantastical William Lithgow, and was good-humoured enough to read and advise upon a poem in manuscript by the same hand which bore the unsavoury title of "The Gushing Tears of Godly Sorrow."[25]

[39]In those days the business of life crowded fast upon boyhood. After the university came marriage as the next step in a gentleman's education. Not far from Old Montrose stood the castle of Kinnaird, where Lord Carnegie[26] dwelt with six pretty daughters. There Montrose had often visited, and there he fell in love with Magdalen, the youngest girl. The match was too desirable for opposition either from the Carnegies or from the young lord's guardians, and the children—Montrose was only seventeen—were married in the parish church of Kinnaird on November 10, 1629. In the marriage contract Lord Carnegie bound himself "to entertain and sustain in house with himself, the said noble earl and Mistress Magdalene Carnegie, his promised spouse, during the space of three years next after the said marriage."[27] Accordingly the young couple remained at Kinnaird for a little over three years, until Montrose came of age, and there two of their four sons were born.[28] They were years of quiet study, the leisurely preparation which is all too rare in youth for the necessities of manhood; and they were the only season of peaceful domestic life which Montrose was fated to enjoy. The famous Jameson portrait, given by Graham of Morphie as a wedding gift to the young countess, shows him in those years of meditation, when he was scribbling his ambitions in his copy of Quintus Curtius. It is a charming head of a boy, with its wide, curious, grey eyes, the arched, almost fantastic, eyebrows, the delicate mobile lips. Life was to crush out the daintiness and gaiety, armour was to take the place of lace collar and silken doublet; but one thing the face of Montrose never lost—it had always an air of hope, as of one seeking for a far country.

In June 1633 Charles came to Scotland to be crowned. Such an occasion was well suited for the introduction of a young nobleman to the court, for in that year Montrose attained his majority, his father-in-law was high in the royal favour, and his brother-in-law Napier was one of the four peers chosen to hold the canopy over the king's head. That the world expected his presence is shown by his friend William Lithgow's recommendation of his merits in the preposterous poem, "Scotland's Welcome to her Native Son and Sovereign Lord, King Charles." But when midsummer came he was on a foreign shore. The reason may be traced in the scandal connected with his sister's husband, Sir John Colquhoun, which in the beginning of that year was the talk of Scotland. The laird of Luss, in company with a German necromancer of the name of Carlippis, had fled from his lawful wife, carrying with him his sister-in-law, the little Lady Katherine, who had for a time been Montrose's companion in his Glasgow lodgings. The malefactor was outlawed and excommunicated, returning fourteen years later to be received into grace by Church and State; the unhappy girl disappears from history. With such a family horror on his mind, Montrose sought the anodyne of new scenes and fresh faces.

We know little of his travels. He started probably in the beginning of 1633, accompanied by his secretary of St. Andrews days, John Lambie, and young Graham of Morphie. According to Burnet, his travelling companion was Basil Fielding, Denbigh's son and Hamilton's brother-in-law, who flung in his fortunes later with the Puritan party. He financed his journey by drawing bills on William Dick of Braid through the latter's "factors" in Paris. The winter of 1633-34 was spent at Angers, where he no doubt was a pupil of the famous school of arms. In the old library at Innerpeffray there is still preserved a French Bible which he bought on his travels, scribbled throughout with mottoes which had caught his fancy, such as "Honor mihi vita potior" and "Non crescunt sine spinis." In Rome he met Lord Angus, the future Marquis of Douglas, and others of the Scots nobility, and dined with them at the English College there. He studied all the while—"as mu[41]ch of the mathematics as is required of a soldier," wrote his faithful adherent Thomas Saintserf, "but his great study was to read men and the actions of great men." It is a phrase which aptly describes the attitude of high dedication in which the young man passed his youth. He went gravely about the business of life, and already had made certain of renown, though careless enough of happiness. Long afterwards, to foreign observers like the Cardinal de Retz, he seemed like one of the heroes of Plutarch, and there was something even in his boyish outlook of the high Roman manner. It was at this time that his interests began to move strongly towards the military art. Europe was in the throes of the Thirty Years' War, half its gentry were in arms, the great Gustavus was but two years dead, and in court and college the talk was all of leaguers and campaigns.

The descriptions of his person and habits at this date are familiar; of middle stature and gracefully built, chestnut hair, a clear fresh colour, a high-bridged nose, keen grey eyes; an accomplished horseman, and an adept at every sport which needed a lithe body and a cool head.[29] On his manner all accounts are agreed, and most accounts are critical. He was very stately and ceremonious, even as a young man, in no way prepared to forget that he was a great noble, except among his intimates. To servants and inferiors he was kindly and thoughtful, to equals and superiors a little stiff and hard. Burnet says of him that he was "a young man well learned, who had travelled, but had taken upon him the port of a hero too much."[30] "He was exceedingly constant and loving," a friend wrote, "to those who did adhere to him, and very affable to such as he knew; though his carriage, which indeed was not ordinary, made him seem proud." One is reminded of Sir Walter Ralei[42]gh, whose "næve," says Aubrey, "was that he was damnable proud." Adventurous and imaginative youth is rarely free from the fault; its sensitive haughtiness is both defensive armour and a defiance; it believes itself destined for great deeds, and a boyish stateliness is its advertisement to the world of the part it has set itself to play.

Montrose returned home in 1636, in his twenty-fourth year—a figure of intense interest to the Scottish faction-leaders, and of some moment to the king's court. He was altogether too remarkable to please the Marquis of Hamilton, who was the interpreter of Scottish business to the royal ear, and for the first time he came into conflict with one with whom he was to fight many battles. James, third Marquis, and soon to be first Duke, of Hamilton, was not the least futile of the many schemers of his day. A vain, secret being, a diligent tramper of backstairs, and a master of incompetent intrigue, he is throughout his career the sheep in wolf's clothing. He looks at us from the canvas of Vandyck, a martial figure, grasping a baton, but in his face we can detect what Sir Philip Warwick noted—"such a cloud on his countenance that Nature seems to have impressed aliquid insigne"—something crack-brained, uncertain and tortuous, a warning that this was no man to ride the ford with. The royal blood in his veins gave him high ambitions, and his fierce old mother, Ann Cunningham of Glencairn, strongly coloured these ambitions, so that he was for ever halting between King and Covenant, dreaming now of winning Scotland for his master, and now of reigning himself in some theocratic millennium. His life was one long pose, but the poses were many and contradictory, and the world came to regard as a knave one who was principally a fool. Burnet, the Hamilton champion, has done his best for his memory, but the verdict of history has been written by Clarendon, who was no ill-wisher to his house. "His natural darkness and reservation in his discourse made him to be thought a wise man, and his having been in command under the King of Sweden,[43] as his continual discourse of battles and fortifications, made him to be thought a soldier. And both these mistakes were the cause that made him to be looked upon as a worse and a more dangerous man than in truth he deserved to be."[31]

When Montrose reached London he appeared at court, and naturally asked Hamilton to be his sponsor, announcing his wish "to put himself into the king's service." Hamilton did his best to dissuade him by representing Charles as the foe of Scottish rights, and then promptly sought out the king to tell him that Montrose, by reason of his royal descent, was a danger to the royal interests, and should be discouraged. The upshot was that the traveller was received by Charles with marked coldness. The king spoke a few chilly words, gave him his hand to kiss, and turned away. It was enough to discourage the most ardent loyalist, and the rebuff made it certain that personal affection for his monarch would play no part in determining the young man's conduct on his return to his own country.

It is bad policy to represent a political system as having no charm but for robbers and assassins, and no natural origin but in the brains of fools or madmen, when experience has proved that the great danger of the system consists in the peculiar fascination it is calculated to exert upon noble and imaginative spirits.

Coleridge, The Friend.

To understand the decision with which Montrose was confronted on his return, we must examine the elements of the storm which was now gathering to a head in the north, and to this end cast our eyes back over a tangled century of Scottish history.

The Reformation in Scotland has been often misconceived as a sudden and universal turning from an old way of life, and as sudden a birth of Presbytery fully matured in creed, discipline, and constitution. In reality it was a slow and halting process, where at the start only one thing was determined—the breach with Rome; and the positive structure suffered long delays and hesitations. The masculine genius of Knox was better fitted for action than for constructive thought; he knew when to defy and when to yield, for, in F. W. Maitland's phrase, a shrewd worldly wisdom underlay his Hebraic frenzies; but he was nobly inconsistent, his views passed through baffling permutations, and, in spite of the acumen of his mind, the fabric he reared was neither well planned nor soundly masoned. But on the negative side his work was final. The old building had been razed to the ground, so that in Scotland there was at no time the remotest chance of a cou[45]nter-Reformation. The faults of the pre-Reformation Scottish Church have doubtless been too darkly painted. In many ways its rule was beneficent, and it was rarely oppressive, but it had little hold upon the mind of a people which, in the Middle Ages, was notably careless about Rome. When Scotland found religion, she found it in a form which made her historic Church seem the flat opposite of the commands of Omnipotence. Moreover, the Renaissance came to her mainly through the Reformation, and, besides the religious impulse, there were stirrings towards democracy and freedom of thought which were satisfied by her new creed. Also there was her ancient dislike of foreign meddling. Rome became a hissing and a reproach, though men might differ hotly about what should take its place. When Knox thundered against the "diabolical," "rotten," and "stinking" ritual which had once been a familiar and comforting part of the people's life, when he declared that the mass was more odious in God's sight than murder, he had the assent of the bulk of the nation. "They think it impossible to lose the way to Heaven," wrote Sir Anthony Weldon of the Scots, "if they can but leave Rome behind them." On the destructive side the work was complete.

We may date the Scottish Reformation from the first "Band" of December 1557, which denounced the abuses of Rome and demanded the introduction of the English Prayer-book; but it was not till the Edinburgh Parliament of 1560 that we see the dawnings of Presbytery. Presbyterianism, as we understand the word to-day, is distinguished by its theory of church government, its ritual, and its creed. In each domain its special principles were slow to establish themselves.

Take the matter of church government. The cardinal doctrine of the priesthood of all believers was no doubt there in germ from the beginning, but at first there was little besides. The Presbyterian belief in the equality of ministers came neither from Calvin nor from Knox; Knox's "superintendents," as diocesan chiefs, were strangely like bishops, and the first refor[46]med Scottish Church was a limited episcopacy. It was Andrew Melville who introduced the doctrine of ministerial parity, and made bishops an offence not only against the Scriptural conception of the Church, but against the new notion of democracy. "Ye may have bishops here," the minister of Dunfermline told King James, "but ye must remember to make us all equal; make us all bishops, else will ye never content us."[32] The first Book of Discipline of 1561 accepted a hierarchy; the second Book of Discipline twenty years later swept it away. But the battle was not won; its fortunes seesawed during the reign of James, according as the monarch felt his power, for he had reached the firm conclusion that a hierarchy was a necessary protection for the throne against the potential anarchy of Presbytery. In 1584 came the Black Acts, and a short-lived royal triumph; in 1592 the king was forced to accept a full Presbyterian polity; by 1600 he had won again, and bishops sat in Parliament. His accession to the English throne gave him a new authority, the Melvilles were exiled, and, by means of packed ecclesiastical conventions, which he called General Assemblies, he had the Act of 1592 repealed and episcopacy established by law. But it was no more than a parliamentary episcopacy, scarcely affecting the life of the people, since kirk sessions, presbyteries, and synods continued to meet, and a staunch Presbyterian could write in 1616: "At that time I observed little controversy in religion in the Kirk of Scotland, for though there were bishops, yet they took little upon them."[33] In the early years of the reign of Charles I. the familiar Presbyterian régime was the rule in Scotland, with bishops affixed to it as a meaningless adminicle.

In the same way the General Assembly—that palladium of the new Church—was slow to come to maturity. When it was introduced in 1560, it was a copy of the national synod of the French Church. It was not a gathering of ecclesiastics, but repres[47]entative of the whole religious life of the people, containing both clergy and laity popularly elected. From the start it possessed a representative authority which was lacking in the Scottish Parliament, and it presently became its rival. In the confused early years of James it wielded great powers and interfered much in secular policy—not without reason, for at the time every political problem had a religious connotation. But after the king's victory in 1597 its influence declined, and before the end of his life it became an instrument in his hands. Andrew Melville had stated its claims so high that the civil authority could not choose but oppose them. "Thair is twa Kings and twa Kingdoms in Scotland," he had told his master. "Thair is Chryst Jesus the King and his Kingdom the Kirk, whase subject King James the Saxt is, and of whase Kingdom nocht a King nor a Lord nor a heid but a member. And they whom Chryst has callit and commandit to watch over the Kirk and govern his spirituall Kingdom has sufficient power of him and authoritie sa to do." This might seem a reasonable statement of spiritual independence, were it not that the particular Assembly to which James objected had been called to discuss a question of secular politics.

We see, indeed, through the whole period between 1560 and 1638 the hardening and the magnifying of the claims of the new Church in other than legitimate matters of spiritual doctrine and discipline. It was this arrogance that made James and Charles desire a system which would bring the ecclesiastical leaders directly into the body politic, and so make them responsible to their sovereign; the trouble was that the real leaders saw that their power lay in being detached from King and Parliament, the chiefs of an imperium in imperio. There is no warrant for this separation to be found in Calvin. A preacher at Nîmes took to overthrowing images and altars, declaring that it was a matter of conscience. "God," said Calvin, "never commands any one to overthrow idols, except every man in his own house, and, in public, those whom He has armed with authority.[48] Let that firebrand show me by what title he is lord of the land where he has been burning things."[34] This was also the view of Knox, though he spoke at different times with different voices. He bade his Berwick congregation give due obedience to magistrates, however ungodly, without tumult or sedition, and "not to pretend to defend God's truth and religion, ye being subjects, by violence or sword, but patiently suffering what God shall please be laid on you for constant confession of your faith and belief"; seven years later he was advising the faithful in England that "a prince who erects idolatry . . . must be adjudged to death." But his considered view seems to have been that in a Christian state the last word, even in religion, lay with the civil authority. "The ordering and reformation of religion doth especially appertain to the Civil Magistrate. . . . The King taketh upon him to command the Priests."[35] The true father of the doctrine of the divine right of Presbytery was Andrew Melville, and under his influence the new presbyter became, in the extravagance of his claims, but too like the old priest. When ministers, called to account before the Privy Council for preaching civil sedition, declared that they could only appear before a Church court, they were laying down a principle, ancient indeed, but none the less destructive of civil society. Elizabeth in England saw what was coming, and in 1590 counselled her brother of Scotland: "Let me warn you that there is risen, both in your realm and mine, a sect of perilous consequence, such as would have no kings but a presbytery, and take our place while they enjoy our privileges, with a shade of God's Word, which none is judged to follow right without by their censure they be so deemed."[36] The comparative impotence of the Scottish Kirk in the early years of Charles I. should not blind us to the fact that in the minds of some of its ablest divines there was developing a perilous doctrine of spiritual despotism[49].

The question of ritual was also unsettled. The first reformers in Scotland had no objection to the use of settled forms in public worship: none of them would have understood the objection of later Covenanting extremists even to the Lord's Prayer. In 1557 the Second Book of Edward VI. had been recommended, and was generally used in churches, till Knox secured its supersession by the Genevan Book of Common Order. The abhorrence of prescript prayer came into Scotland from the English Puritans. Knox disliked many things in the English Prayer-book, for it was his business to magnify differences between the old worship and the new, so as to stimulate Protestant fervour. He objected to kneeling at communion, because he believed—without historical warrant—that the first disciples sat, but he told his Berwick congregation that they might kneel if the magistrates commanded it, and made it clear that it was not retained for "maintenance of any superstition," like "the adoration of the Lord's Supper." Later his attitude stiffened, and he considered that kneeling at the Lord's table, responses, singing of the litany, services on saints' days, and the use of the cross in baptism were "diabolical inventions." But these were personal opinions; he disliked equally the imposition of hands at the ordination of ministers, which has long been a settled Presbyterian usage. The Scottish Kirk was content to have a liturgy, but it wanted its own Genevan version, and had the authorities been wise they might have found a method of reuniting the worship of both sides of the Tweed by some such eirenicon as John Hales dreamed of—a public form of service embracing only those things upon which all Christians were agreed.[37] Scotland was willing to accept a ritual, but it must not be too suggestive of the Roman, and it must be her own and not an imposition from England. The five Articles of Perth, ratified by Parliament in 1621, enjoined kneeling at communion, the private administration of the sacrament to the dying, baptism in private houses, the confirmation of the young, and[50] the keeping of certain church festivals—all English practices and foreign to the Genevan code: Scotland disliked them, but when they became law there was no further trouble, and, since they were not strictly enforced, they might soon have perished from desuetude. James, indeed, seems to have regarded the Perth Articles as the most he was prepared to demand, and to have guaranteed no increase of English innovations.[38] Scotland had, therefore, a legal ritual, which was imperfectly observed[39] because it was out of tune with the spirit of the Kirk, but not overtly opposed, because it had been established by means of her own law. The real strife would begin if the monarch should arbitrarily impose further Anglican forms upon her, for that would call to arms not only the Genevan purism of the Kirk, but the sleepless nationalism of the people.

At the time which we are now considering only one of the Kirk's foundations had been securely built—her dogmatic creed, which was the Calvinism of Knox's Confession of Faith, accepted by the reforming Parliament of 1560. That stood without cavil, though in the interpretation of its articles there was considerable difference of emphasis. For the rest, the Kirk was a nominal episcopacy, but the bishops were impotent, and the discipline was in substance Presbyterian: her General Assembly was in abeyance owing to royal encroachments, but it was an integral and established part of her, so that at the right moment it could be revived; she had moved far from the moderate Erastianism of Knox, and had come to regard herself as a self-governing commonwealth, wholly independent in all things which by any stretch of language could be called spiritual, and entitled to interfere even in secular politics; her worship was in the main according to the Genevan form, but not universally regular owing to James's ill-obeyed decrees. She was a living organism, the only institution which commanded the loyalty of the majority of the people, and she was a national thing—for she was[51] neither Genevan, Gallican, nor Anglican, but Scottish.[40] Among the mediæval lumber of Parliament, Lords of the Articles and Privy Council, the Kirk stood out like a throbbing power-house among tombs. Whether the land were ill or wisely guided, the chief part of the guiding must be hers.

The ecclesiastical structure is much, but we must look closer at that more vital thing, the spirit which inspired it.

The essence of the Reformation was simplification. The great organism of the Catholic Church, with all its intricate accretions of fifteen centuries, was exchanged for a simple revelation—God speaking through His Word to the individual conscience. The Bible was its palladium, but the question presently arose as to how the Bible was to be construed, once the authority of the Church had been rejected. If the individual soul was the basis of the new creed, so apparently must be the individual judgment. That way lay anarchy and anabaptism, and it was necessary, before the Reformed Church could come into being, to establish some canon of interpretation, otherwise Protestantism would go to pieces. The liberal theologians of the seventeenth century held that the Bible was subject to the ultimate tests of conscience and reason. "The authority of man," said Hooker, "is the key which openeth the door of entrance into the knowledge of the Scriptures." To him the Bible was not a cyclopædia of all knowledge and all truth. "Admit this and mark, I beseech you, what follows. God, in delivering Scripture to His church, should claim to have abrogated amongst them the law[52] of nature, which is an infallible knowledge imprinted in the minds of all the children of men, whereby both general principles for directing of human action are comprehended, and conclusions derived from them; upon which conclusions groweth in particular the choice of good and evil in the daily affairs of this life. Admit this, and what shall the Scriptures be but a snare and a torment to weak consciences, filling them with infinite perplexities, scrupulosities, doubts insoluble, and extreme despairs."[41] This was the creed of Laud and Chillingworth, of John Hales and Jeremy Taylor, and from it followed the view that, if human reason were the ultimate guide to interpretation, diversity of opinion was inevitable and indeed essential. But such a foundation was too insecure on which to found a militant church. Calvin took a bolder course. We know that the Bible is God's Word, not because of the authority of an historic church, but because of the revelation of the Holy Spirit. This revelation must be systematized and made explicit by God's servants, so that the wayfaring man may understand. From this it is a short step to the foundation of a church which is the direct medium of the Holy Spirit, and a repository of inspired interpretation. The second edition of Calvin's Institutes—he was only thirty when it was published—definitely claims to be the canon of Scripture teaching; from it alone the reader may learn what Scripture means. Already the Bible is in a secondary place, and we are not far from Tertullian's doctrine that the regula fidei is not Scripture but the creed of a church.

Calvin was perhaps the most potent intellectual force in the world between St. Thomas Aquinas and Voltaire. Though he rejected in his system whatever the Bible did not warrant, and not, like Luther, only what the Bible expressly forbade, he was in many ways nearer to Catholicism than the German reformer. Like most great men, he was greater than the thing he created. He was a profounder statesman than his[53] followers, and far less of a formalist. He could be so inconsistent as to be accused of heresy: he saw the dangers into which his church might drift, and declared that he had no desire to introduce "the tyranny that one should be bound, under pain of being held a heretic, to repeat words dictated by some one else"; a man to whom Plato was of all philosophers religiosissimus et maxime sobrius, had more affinities with humanism than is commonly believed. But a law-giver must be dogmatic, and the founder of a church must narrow his sympathies. He faced the eternal antinomies of thought—the reign of law and the freedom of human spirit—and provided not a solution but a practical compromise. He begins with the conceptions of an omnipotent God of infinite purity and wisdom, of man cradled in iniquity, and of salvation only through God's grace. The sinner is foreordained—since God orders all things—alike to sin and to destruction. It is the omnipotence of God that he stresses, rather than the fatherhood, for he faces the problem from another angle than Luther: the triviality of the created and the majesty of the creator; the eternal damnation of man unless lifted out of the pit by God's election.

These doctrines and this angle of vision were not new. Origen and Gregory of Nyssa might preach a milder code, but they were the orthodox creed of the Fathers of the Church. Men like Tertullian exulted in contemplating the tortures of the damned. Unbaptized infants, a span long, would burn for ever in hell, in spite of the fact that their creation and death were the direct acts of their Maker. It was the universal mediæval belief, in spite of the questioning of a Socinus; it was the common doctrine of all the Reformers except Zuinglius. "This is the acme of faith," said Luther, "to believe that He is merciful who saves so few and who condemns so many; that He is just who, at His own pleasure, has made us necessarily doomed to damnation. . . . If by any effort of reason I could conceive how God could be merciful and just who shows so much anger and iniquity, there would be no n[54]eed for faith."[42] On such a view man's reason and man's moral sense must alike be discarded as temptations of the devil.

This was the creed of Augustine, stated by him more passionately and harshly than by any Reformer; from him Calvin largely derived his dogmas, but he took the doctrine and discarded Augustine's church. Its central principle, the inexorableness of law, the impossibility of free will, has been held by many secular thinkers from Spinoza to Mill, who would have rejected its theological implications. It was the creed of William the Silent and Coligny and Cromwell, of Donne and Milton and Bunyan—men in whom both conscience and intellect were quick. Only by a noble inconsistency and a tacit forgetfulness could it be a worthy rule of life, and this was in fact what happened. Calvin was greater than Calvinism, and the Calvinist was a humaner and a wiser man than his creed. But with all its perversities it put salt and iron into human life. It taught man his frailty and his greatness, and brought him into direct communion with Omnipotence. It preached uncompromisingly the necessity of a choice between two paths; in Bunyan's words the mountain gate "has room for body and soul, but not for body and soul and sin." It taught a deep consciousness of guilt, and a profound sense of the greatness of God, so that they who feared Him were little troubled by earthly fears. Historically its importance lay in its absoluteness, for a religion which becomes a "perhaps" will not stand in the day of battle. It claimed to be truth, the whole truth, when everything else was a conjecture or a lie. "In God's matters," said Samuel Rutherford, "there be not, as in grammar, the positive and comparative degrees; . . . there are not here true, and more true, and most true. Truth is an indivisible line which hath no latitude and cannot admit of splitting."[43] It brigaded men into serried battalions; the free-lance disappeared; Mr. Haughty, in the Holy War, who declared "th[55]at he had carried himself bravely, not considering who were his foes, or what was the cause in which he was engaged," was duly hanged by the men of Mansoul. A creed which was fighting for its life could not afford to be liberal. "On such subjects, and with common men, latitude of mind means weakness of mind. There is but a certain quantity of spiritual force in any man. Spread it over a broad surface, the stream is shallow and languid."[44]

Calvin's fame rests rather on the church which he created than on the creed which he gave it, for he was a greater legislator than a theologian. It was not in belief alone that safety was to be found, but in belief within a church; in his own words, "Beyond the bosom of the Church no remission of sins is to be hoped for nor any salvation"—a strange return to the ecclesiasticism which he had rejected. He might have said, in the words of a recent Vatican decree, "La Chiesa non è un credo; la Chiesa è un impero, una disciplina." John Knox considered the Genevan Church "the most perfect School of Christ that ever was on earth since the days of the Apostles," and this was the view taken by his successors of the quasi-Genevan edifice which he erected in Scotland. It was divine, guided and inspired by God, and not to be judged by human standards. It could not err, though that fallible thing the human conscience might regard certain of its actions as immoral.[45] It was a complex legal machine, for it was not for nothing that Calvin, like Knox and Donne, was bred to the law, and legal phraseology became the fashion among the divines.[46] Wielding the most awful powers and penalties, acting under the most august sanctions, inspired by a narrow and absolute creed, cunningly articulated so that the whole nation was embodied under its dominion, the Kirk in Scotland[56] was well able to speak with its adversaries in the gate.