| chapter | page | |

| X | THE First Laurier Ministry | 3 |

| XI | The Flood Tide of Imperialism | 59 |

| XII | The United States: 1896-1903 | 119 |

| XIII | The Master of the Administration | 161 |

| XIV | Schools and Scandals | 220 |

| XV | Nation and Empire | 284 |

| XVI | Reciprocity | 346 |

| XVII | In the Shades of Opposition | 384 |

| XVIII | The Great War | 426 |

| XIX | The Closing Years | 491 |

| Appendix | 556 | |

| Index | 559 |

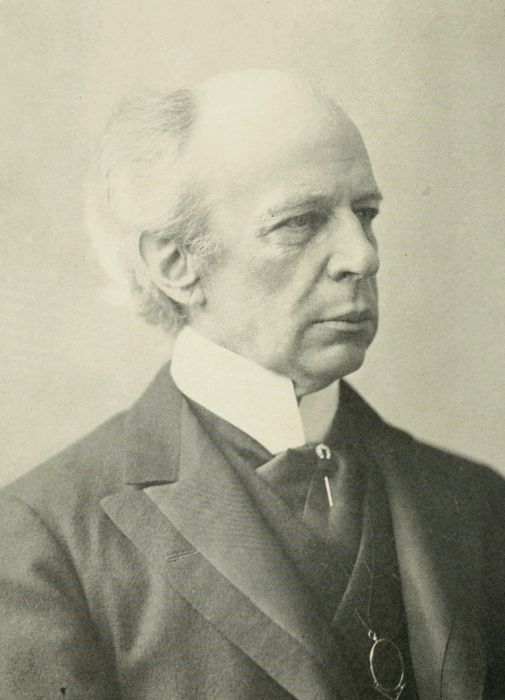

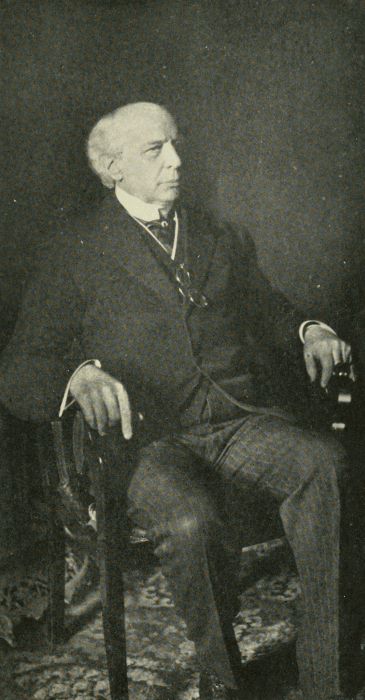

| Wilfrid Laurier | Frontispiece |

| facing page | |

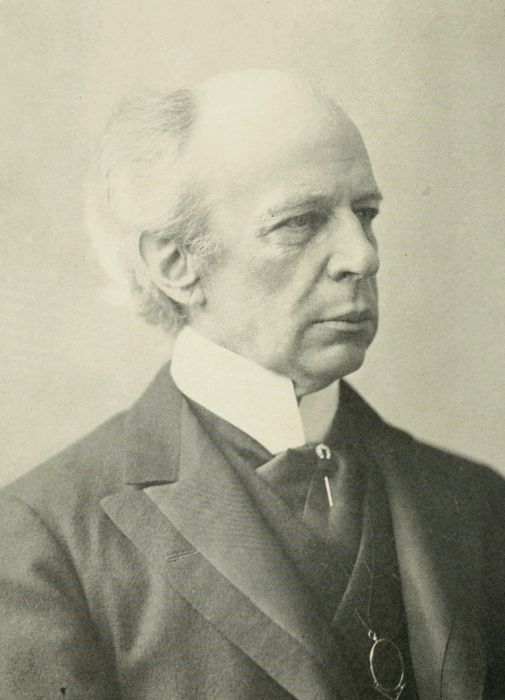

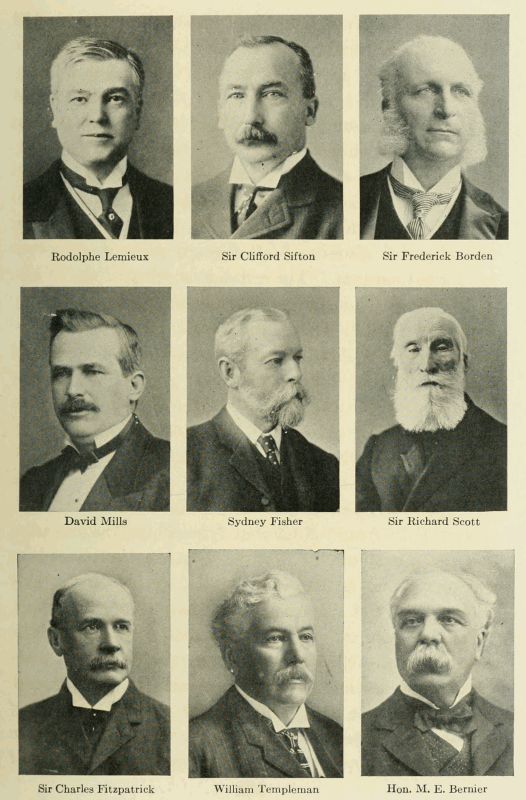

| Group of Ministers | 32 |

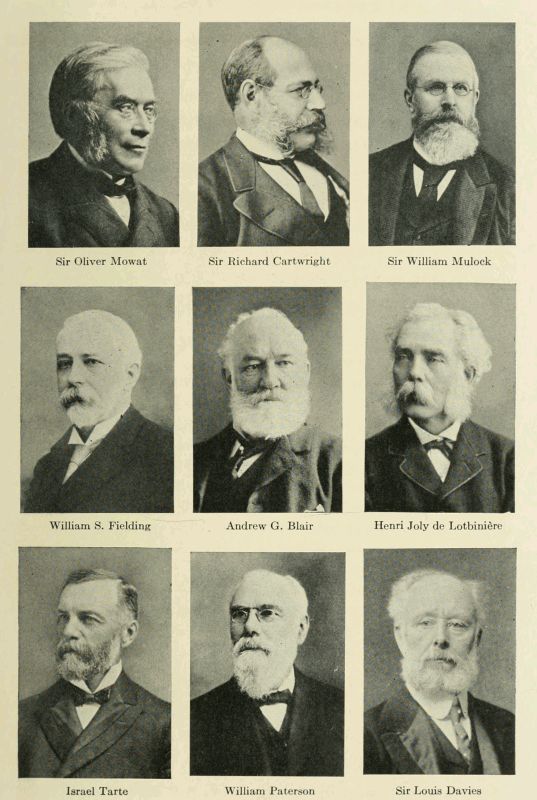

| Mr. Joseph Chamberlain and his Colonial Premiers | 64 |

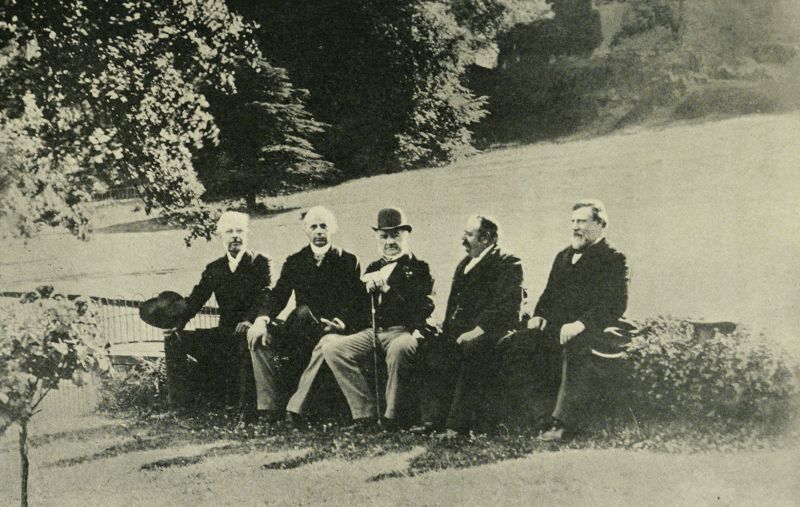

| A Pilgrimage to Hawarden | 80 |

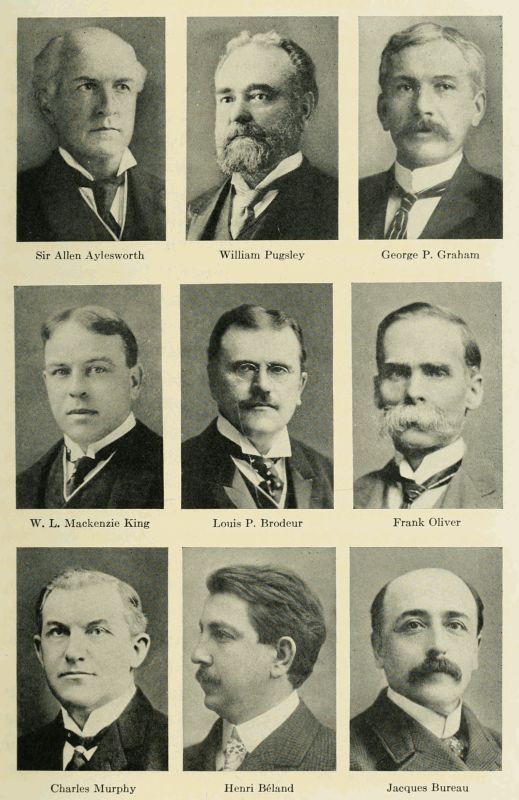

| Group of Ministers | 128 |

| Cartoon by Henri Julien | 192 |

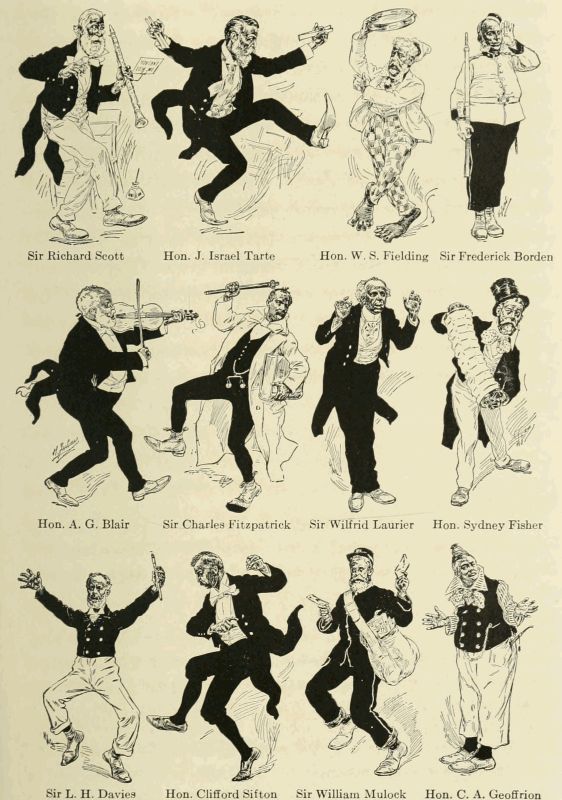

| Henri Julien's "By-Town Coons" | 208 |

| Group of Ministers | 256 |

| Lady Laurier | 272 |

| Laurier's Last Imperial Conference | 304 |

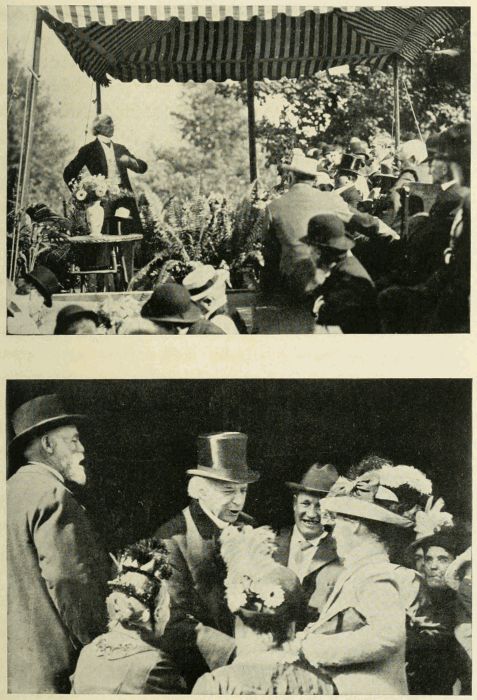

| Campaigning in Western Ontario | 352 |

| Campaigning in Quebec | 368 |

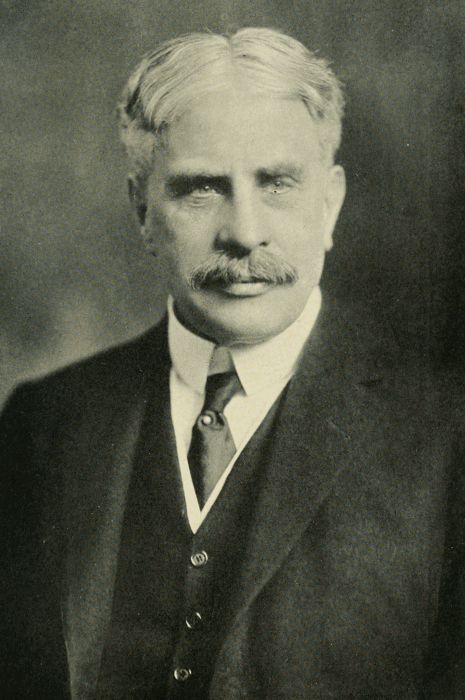

| Sir Robert Borden | 400 |

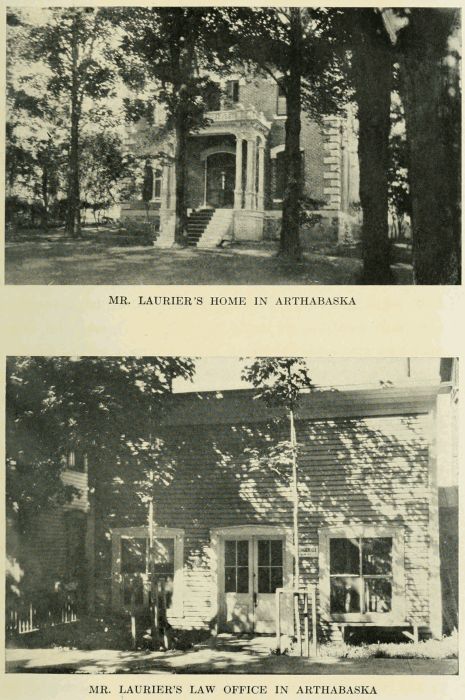

| Mr. Laurier's Home in Arthabaska | 432 |

| Mr. Laurier's Law Office in Arthabaska | 432 |

| Their Golden Wedding Day | 528 |

| Sir Wilfrid Laurier | 544 |

Speeding the Parting Guest—Forming the Ministry—The Laurier-Greenway Settlement—An Episcopal Challenge—An Appeal to Rome—The Beginning of Prosperity—The Opening of the West—The British Preference.

After eighteen years' wandering in the wilderness of opposition, for half the time under Wilfrid Laurier's leadership, the Liberal party had come to power. For fifteen years, the longest unbroken stretch of authority in the country's annals, Mr. Laurier was destined to remain prime minister of Canada. They were to be years crowded with opportunity and with responsibility, a testing-time sufficient to search out every strength and every weakness of the leader or of his administration. It was Mr. Laurier's fortune, and Canada's, that he was to be in control of the country's affairs at the most creative and formative period in its history, in the years when the Dominion was attaining at once industrial maturity and national status.[4]

In June, 1896, these things lay hidden in the future. The immediate question was, when would the defeated ministry resign? Since Mackenzie's resignation in 1878, it had been accepted doctrine that in the event of a decisive defeat a ministry would not await the assembling of parliament and a formal vote of want of confidence, but would resign at once. Sir Charles Tupper made no undue haste in retiring. It was necessary to wind up the work of the departments. It was still more necessary to use the vanishing powers of appointment to reward past service and to buttress future positions. A long list of new senators, judges, Queen's Counsel, revising officers, inland-revenue collectors, was drawn up and presented to the governor-general, Lord Aberdeen, for his formal approval. Lord Aberdeen hesitated to sanction the more important nominations. As the last parliament had voted supplies only until June 30, and as Sir Charles Tupper had not formed his government until after parliament had prorogued, "the acts of the present administration," the governor-general held, "are in an unusual degree provisional." The Senate, after twenty-four years of Conservative and five of Liberal appointments, was overwhelmingly Conservative, and to fill all the remaining vacancies with Sir Charles's nominees would not only keep the scales loaded against the new government for many a year, but would embarrass it seriously at the very outset, blocking Sir Oliver Mowat's accession to the cabinet. The Bench, again, would be overwhelmingly Conservative. On this ground the governor-general, using the[5] discretion the constitution gave him, finally declined to accept his advisers' advice. Sir Charles, after a vigorous protest against this "unwarranted invasion of responsible government," and an endeavour to buttress up his position by appeals to Todd's authority and Mackenzie's example, treated the governor-general's refusal to sign the appointments as an indication of want of confidence; on July 8 he resigned the seals of office, but he never forgave the speeding of the parting guest. The next day Lord Aberdeen called upon Mr. Laurier to form a new administration.

It was not a difficult task to find sufficient cabinet timber. The difficulty was rather an embarrassment of riches. There were many potential ministers, and few portfolios,—fewer, alas, than might have been, had not Liberals in the unrecking days of opposition denounced as extravagant the creation of every new department.[1] There were many interests to weigh.

[6]Mr. Laurier had to hold the balance fairly between his own parliamentary followers and the men in the provincial administrations, between the old Liberal war horses and the eleventh-hour converts, between past service and future capacity, between debating skill and executive power, between province and province and between section and section, alloting Quebec its English-speaking Protestant minister and Ontario its Irish Catholic minister. But the range of choice had been closely narrowed before the election, and it was only necessary now to make some last-moment shifts because of election fatalities or personal idiosyncracies. By July 13 all the new ministers but three had been sworn in.

Mr. Laurier, profiting by the experience of Mackenzie and of Macdonald, determined not to take charge of a department. That would have meant that either, as in Mackenzie's day, the work of policy shaping and party guiding or, as in Macdonald's day, the work of the department would often go undone. As President of the Council, he would be free to give to all the tasks of the government the general supervision he had planned.

For the important portfolios of Justice, Finance, and Railways, Mr. Laurier turned to the provinces. Sir Oliver Mowat, appointed to the senatorial vacancy which Sir Charles Tupper had sought to preëmpt, be[7]came Minister of Justice. Thirty-three years before, young Oliver Mowat had joined the short-lived Sandfield Macdonald-Dorion ministry as Postmaster-General. It was a strange turn of the wheel that brought him back to the central government after a generation's work in other fields, and stranger still the lot which gave him charge of the department against which he had waged so many persistent and so many successful constitutional battles. Though he no longer had the force or the interest in affairs which had marked his prime, Sir Oliver was still full of sage counsel. In the cabinet, his half-century's experience and his shrewd knowledge of men helped a dozen strong ministers of individual ways and training to become a team; while to the Scotch Presbyterian voters, his presence in the ministry was unimpeachable proof of its thorough soundness and respectability. William Stevens Fielding, for twenty years a Halifax newspaper man, for another ten premier and unquestioned master in his native province, gave up his Nova Scotia post to become Minister of Finance. In central and western Canada he was not well known, but it was not long before his caution and efficiency in administration and his hard-hitting power in debate had given him a foremost place in parliament and in party council. Andrew George Blair, premier of New Brunswick, who had been equally at home in Liberal and in coalition ministries, was a more uncertain quantity, shrewd, undoubtedly experienced in all the ways and wiles of the most efficient school of politics (New Brunswick) in America, and as a Maritime-prov[8]ince man, he was thoroughly familiar with the traffic and patronage potentialities of the Intercolonial, now assigned to his charge as Minister of Railways and Canals. From the West it was understood that a member of the Manitoba administration might be chosen to take charge of the Department of the Interior, but for the time the post was left unfilled.

From his Quebec followers in parliament, Mr. Laurier chose three men for portfolios. Israel Tarte, defeated in Beauharnois, but elected later by acclamation in St. Johns-Iberville, took charge of the largest spending department, Public Works, the department which he had assailed and exposed in his Langevin charges. Henri Joly de Lotbinière, member-elect for Portneuf, premier of Quebec for a brief space after the Letellier coup d'état, leader of the provincial Liberals until Mercier's union with the Castors in the Riel days, a Protestant who had won the confidence of a Catholic province, a seigneur who embodied the finest traditions of courtesy and honour of his order, a man for whom Wilfrid Laurier had profound respect and natural sympathy, became Controller of Inland Revenue. Sydney Fisher, one of the few men of leisure in Canadian politics, who had followed his university training by public service in politics and in progressive farming in the Eastern Townships, was now back in parliament after a term's absence spent largely in the political organization of Quebec. Though labelled by his critics "gentleman farmer," he was still a farmer, and immensely better fitted for his new post as Min[9]ister of Agriculture than the lawyers and doctors and brewers and near-farmers who had preceded him. Two members joined the cabinet without portfolio: C. A. Geoffrion, a leader of the Montreal bar, and professor of civil law in McGill, fellow office-bearer with Wilfrid Laurier thirty years before in L'Institut Canadien, brother of the Felix Geoffrion who had been his colleague in Mackenzie's ministry, and son-in-law of Antoine Aimé Dorion, and R. R. Dobell, head of the well-known Quebec lumbering firm, who had been half detached from the Conservative party by the McGreevy scandals, and had fully accepted the Liberal platform on the trade and school issues in the late election. Charles Fitzpatrick, another citizen of old Quebec who had won fame as counsel for Riel in 1885, and for Mercier and for McGreevy and Connolly in later days, and had held a seat in the provincial house from 1890, when he had declined a post in the De Boucherville Conservative ministry, until 1896, took the Solicitor-Generalship, which by custom formed part of the ministry but not of the inner cabinet where general policy was determined.

Among Ontario members of the federal party, Sir Richard Cartwright stood foremost in service and repute. It had been assumed by many that upon a Liberal victory he would return to his old post of Finance. But he had made many enemies. Though it was not true, as rumour ran, that a deputation of bankers had protested to Laurier against his reappointment, in the eyes of the business world he was identified, rightly or wrongly, with a policy of doctrinaire and ruthless free[10] trade. In determining to offer the portfolio of Finance to Fielding rather than to Cartwright, Laurier was influenced not so much by the desire to reassure the business world as by his conviction that for this most important of all the ministry's tasks, the tried administrative capacity and balanced judgment and the younger years of William Fielding were the qualities most needed. Mr. Fielding's acceptance was contingent on Sir Richard's assent. To Sir Richard the post of Minister of Trade and Commerce was offered. He took the post, and gave loyal service to the country and to the party for many a year, but never again with the old joy and confidence in combat, and never with complete confidence in all his colleagues. William Mulock, Toronto lawyer and York farmer, known at election times as "Farmer Bill," the most vigorous and able of the Ontario group, a good fighter, a good hater, of dominating will and high ambition, became Postmaster-General. Richard W. Scott, member of Assembly and Commons and Senate since 1857, and famed as the maker of the Act of 1863 which firmly established Upper Canada's separate schools, and of the Act of 1878 which gave counties local option to prohibit the retail sale of liquor, was chosen Secretary of State. William Paterson, a successful manufacturer who had coined the cry which had done much service, "Has the N. P. made you rich?" a speaker of stentorian power, slashing in debate, but too kindly ever to leave a smarting wound, became Controller of Customs. His post, like Sir Henri Joly's, was not of cabinet rank, representing, as it did, Thompson's[11] experiment in under-secretaryship, but at the first session both were made full ministerial and cabinet positions.

From the Maritime provinces, besides Fielding and Blair, two ministers were chosen. Louis H. Davies, lawyer, bank president, premier in the Island, member at Ottawa since 1882, had been for many sessions the foremost Maritime Liberal, and so predestined for the portfolio of Marine and Fisheries. Frederick Borden, doctor, banker, militia surgeon, had held a seat in every parliament but one since 1874, and by his long interest in military matters had qualified for new honours as Minister of Militia and Defence.

When all the posts were filled, there were seventeen ministers, including two without portfolio, or one ministerial place for every seven Liberal members. Even so, many men of outstanding ability and service could not be included. Of the Quebec members, many were young, and were yet to earn their spurs. From Ontario there were men of experience and personality, John Charlton, James Sutherland, James Lister, George E. Casey, George Landerkin, M. C. Cameron, John Macmillan, W. C. Edwards, Thomas Bain, who continued to give effective service as whips or private members. James D. Edgar, one of the most aggressive of the Ontario delegation, was elected Speaker of the Commons. One expected name was missing,—that of David Mills. His long service, his rank as the senior Ontario member and his mastery of constitutional issues, had marked him out for cabinet rank again. But[12] he had been defeated in his old riding. It would have been possible to find a seat for him in the Senate, as was done for Sir Oliver, or in the Commons, as was done for William Paterson, who also had gone down in his home constituency, if Mills had been deemed indispensable. As it was, assurance was given of a cabinet post later; and when in November, 1897, Oliver Mowat resigned to become Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario, David Mills was appointed Minister of Justice. Perhaps more serious, for the party's future, was the inability to find cabinet place for Dr. Benjamin Russell or for D. C. Fraser, of the Nova Scotia contingent. One very interesting experiment was blocked by death. D'Alton McCarthy, to whom in earlier days the French tongue and the Catholic religion had been anathema, had in time so broadened and mellowed that he came to look forward with pride to serving under a French-speaking and Catholic premier. It had just been arranged, in 1898, that he should enter the Laurier government, as Minister of Justice, when his death, resulting from a runaway accident, ended an alliance which might have had a material bearing on the future of Liberalism in Ontario.[2]

As it was, the ministry was an extraordinarily able one,—none so strong before or since. In individuality, [13]in varied ability, in administrative capacity, in constructive vision, in internal unity and in integrity, it could safely challenge comparison. Time was to dull the edge of zeal, to emphasize differences, to sap moral resistance, in more than one case, but that was in the twilight hour; the morning was full of high promise.

The cabinet's first task was to settle the Manitoba school question. Until this was done, there could be no peace, no opportunity for constructive work. The eleventh-hour negotiations between Ottawa and Winnipeg and the result of the elections had made clear the bounds within which agreements must be sought. It was clear that a federal remedial law was out of the question except as an absolutely last resort; that relief for the minority must come by provincial legislation; that the province would not consider for a moment the re-establishment of separate schools, but that there was a possibility of securing provision for separate religious teaching and similar adjustments within the framework of the existing system. Preliminary discussions with Mr. Greenway and Mr. Sifton indicated the possibility of agreement, and accordingly it was considered unnecessary to appoint the commission of inquiry suggested when the two governments stood apart.

In August, after some preliminary correspondence, Messrs. Sifton, Watson and Cameron, of the Manitoba government, came to Ottawa, and there threshed out the solution with a sub-committee of the cabinet. It became apparent that the three points upon which con[14]cession might be made were: separate religious exercises, a teacher of the minority's faith, and the use of the French language in the schools. To reach agreement upon details, as for example, whether the minimum attendance essential to secure the first two privileges should be sixty, as the province proposed, or a smaller number, and to debate the possibility of further concessions as to text-books, teachers' licenses, and administration, weeks of consideration were required. It was not until the middle of November that a settlement was effected.

In the meantime the question had arisen as to how far the minority could be brought into the agreement. It was desirable to secure their assent to an agreement made in their behalf; yet it was plain that so far as their ecclesiastical spokesmen were concerned they would not formally assent to anything short of the impossible. Whether consulted or not consulted, they would make trouble. One of the leading representatives of the minority, Mr. Prendergast, who had resigned his post in the Greenway cabinet when the measures of 1890 were passed, was consulted, and agreed that the compromise proposed was the best attainable. Through Israel Tarte, Mgr. Langevin was sounded, with results less happy than the sanguine Minister of Public Works foretold:

My Dear Mr. Laurier:

. . . This is how things stand: Archbishop Langevin stands firm for the right to organize Catholic school districts. In[15] other words, he demands the re-establishment of separate schools, which, as you know, is out of the question. I have not shown him the agreement, for I believe that he would immediately have taken advantage of it to raise a row. The priests who surround him are fanatical and full of prejudice. The Archbishop, however, seems to me to be coming back to a more moderate position, and I do not think he will make a disturbance. Our relations have been very cordial. I have tried to learn his views and to pacify him, by making him realize more clearly the unfortunate side of the present situation for Catholics. In fact, half the French schools are closed and about 1500 French-Canadian children are to-day without instruction.

Prendergast and the most intelligent among the French-Canadians will support our arrangement. I enclose an interview prepared by Mr. Prendergast which should be given to the press the day of the publication of the agreement—not before.

A long habit of absolute submission to the clergy has made my mission here very difficult. Everyone is scared. Further, we have no support in the Catholic press of Manitoba, and our friends are left to the mercy of the "Manitoba" and of the "North-West Review," which is edited by Father Drummond and is extremely violent. . . .

In brief, the position is this: The French Liberals, guided by Prendergast, will support us, and within a year at latest, practically the whole community will have accepted the situation effected by the present agreement.

Mr. Tarte found it necessary also to keep an eye on the provincial ministers. He writes the next day:

I have just telegraphed you not to adopt any order-in-council regarding the Manitoba schools until I return. I hope you will adopt my suggestion. It is in fact essential to the success of the work of conciliation which we have undertaken and which above everything calls for good faith. If the proposed amendments are put into effect in a spirit of[16] friendship and good will, all will go well. If, on the contrary, they are enforced in a niggardly spirit, nothing good will come of them. I have met all the ministers, including Mr. Greenway, and they seem to me to realize the necessity of understanding and conciliatory action.

There is no reason why the Federal government should express satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Let the legislature adopt the proposed amendments; let them be put in force. If, as I have no doubt, the Catholics express themselves as satisfied, the last word will have been said. But it would be extremely imprudent to tie ourselves now, and thereby to give our adversaries in parliament ground for attack. Our rôle hitherto has been to act as amici curiæ. Let us stick to that. This is the position which I have taken with the Catholics here. I have promised them to continue our good offices in the application of the law. . . . Sifton will ask you for an order-in-council approving the settlement. Let him wait, telling him that it will not be advisable to do anything before my return. . . .

The settlement embodied three concessions. First, religious teaching was to be carried on between half-past three and four o'clock, by any Christian clergyman or his deputy, when authorized by a resolution of the local board of trustees or requested by the parents of ten children in a rural or twenty-five in an urban school. Different days or different rooms might be allotted different denominations; no children were to attend unless at the parents' desire. Secondly, at least one duly certificated Roman Catholic teacher was to be employed in urban schools, where the average attendance reached forty and in village and rural schools where it reached twenty-five, if required by parents' petition; similarly, non-Roman Catholic teachers were to be employed[17] when requested by a non-Catholic minority. Thirdly, "when ten of the pupils in any school speak the French language or any language other than English, as their native language, the teaching of such pupils shall be conducted in French, or such other language, and English upon the bilingual system." The provincial government also agreed that fair Catholic representation in advisory council, inspectorships and examining boards would be kept in mind in the administration of the act. In essence, the agreement left the system of public schools intact, but secured for the minority distinct religious teaching, and, where numbers warranted, teachers of their own faith and the maintenance of the French tongue. The language clause was framed in general terms by the provincial authorities in order to make it apply to the German Mennonites as well as to the French Catholics.

The question at once arose,—how had the settlement been effected? Which side had given way? Had the Manitoba government played politics and made concessions to Wilfrid Laurier which it had refused to Mackenzie Bowell? Had the Laurier government accepted for the minority less than the Bowell government would have secured for them? The fact was that the terms, as was inevitable, were a compromise, but a compromise consistent with the essential principles of both parties to the negotiation. The Manitoba government was doubtless readier to negotiate with a Liberal than with a Conservative government, and with exponents of sunny ways than with the wielders of "big[18] sticks." Yet it had adhered to its essential position, refusing to agree either to the restoration of a Catholic school system wholly separate and independent in organization, as the Remedial Bill had provided, or to the establishment, as the Dickey proposals involved, of a system within a system, the segregation of Catholic children, in towns and cities, in separate school buildings or rooms, for secular as well as religious purposes. This agreed, it had assented to all the other concessions for which the Dickey delegation had stood out, and which others now proposed. The Laurier government believed that the agreement was of more real value to the minority than any which could previously have been secured. The Remedial Bill would have been unworkable; the Dickey proposals in part were equally impracticable, while in important details they fell short of what was now secured. Definite religious teaching in the tenets of the Roman Catholic or any other faith was made possible in the only way compatible with unity in secular instruction, by optional instruction at the close of the day. The representation in practice, though not by statute, of Roman Catholics on administrative bodies, and an understanding as to text-books, were common ground. The provision for a Roman Catholic teacher was a modification of one of the Dickey proposals. The new agreement went beyond the Dickey proposals in providing that Roman Catholic children might in all cases be exempted from the standard religious exercises. It added the provision, arising, curiously enough, out of an amendment to the Remedial[19] Bill moved by D'Alton McCarthy himself, for instruction in French.

The announcement of the settlement, on November 19, met very wide approval. Mr. Prendergast, in the interview to which Mr. Tarte refers, pointed out that fifty-one Catholic schools were closed, some since one, some since two, some since four years; that twenty-five others had come under the Public Schools Act, with its standardized religious instruction; and that of the thirty-two schools supported by private contributions as parish schools, half would have to be abandoned or turned into public schools within a year; the new agreement, while not all that could be desired, was worth a fair and honest trial; much would depend upon the spirit of its administration. The Anglican archbishop of Rupert's Land, an upholder of denominational teaching, agreed the settlement was the best that could be made. Dr. Bryce, Isaac Campbell, R. T. Riley and other leading Winnipeggers endorsed it. In Ontario, D'Alton McCarthy and E. F. Clarke spoke for the Conservative opponents of the Remedial Bill in approving it as a reasonable and satisfactory compromise: "Laurier has kept faith," Mr. Clarke declared. "La Patrie" welcomed the passing of evil days. From East to West the overwhelming opinion was approval of a settlement reasonably fair in itself and likely to ensure peace at last.

But approval was far from unanimous. As usual, extremes met. The Grand Orange Lodge of Manitoba denounced the settlement as a betrayal of the[20] national schools, an insidious recognition of denominational pretensions. Senator Bernier and A. C. LaRivière, leaders of the French-Canadian Conservatives of Manitoba, at a mass meeting in St. Boniface attacked it as a wholesale and disgraceful surrender of the minority's rights; no settlement could be accepted which had not previously been approved by the archbishop. Father Cherrier, of St. Boniface, declared that the Church was not content with half an hour for God. Archbishop Langevin sounded a call to arms: "I tell you there will be a revolt in Quebec which will ring throughout Canada and these men who to-day are triumphant will be cast down. The settlement is a farce. The fight has only begun." The next week he opened ten parish schools. In the far East, Archbishop O'Brien, whose flock enjoyed privileges much less extensive, attacked "the cynical injustice ... of this feeble compact of unscrupulous expediency." In Quebec, Archbishop Begin, in a circular letter, declared:

No bishop wants nor can approve the so-called settlement of the Manitoba school question, which, in a word, is based upon the indefensible abandonment of the best established and most sacred rights of the Catholic minority. His Grace the Archbishop of St. Boniface has sounded an immediate and energetic protest against this agreement; in so doing he has done nothing but fulfil his duty as a shepherd and followed the directions of the Holy See. He could not but defend his flock.

"La Semaine Religieuse," the official organ of the[21] Archbishop of Montreal, voiced the prevailing ecclesiastical opinion:

The Manitoba school question is not settled; it merely enters a new phase.... In Manitoba, Catholics and French-Canadians are not beggars nor strangers, to be content with crumbs. We will demand the Catholic school, school districts, books, teachers, and exemption from taxes. All constitutional and legal means of defence will be used before consenting to the rising generation being led into religious and national apostasy. There is no danger of His Eminence the Holy Father assenting: the signal for retreat will never come from Rome.

To one bishop of moderate views Mr. Laurier addressed a reasoned defence of the settlement:

30 November, 1896.

Monseigneur:

. . . Your Grace may perhaps tell me that these concessions

do not go far enough. Was it possible to secure more?

That is the first point to determine.

In the first place, I must meet the objection so often urged, that it is not a question of knowing whether it was possible to secure more: "the constitution as interpreted by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council declared that the Catholics had the right to the complete re-establishment of separate schools." I submit that on this point there is complete misunderstanding, and I believe this will be easy to demonstrate.

. . . The text of the judgment authorises merely an amendment to the existing law, and not the abrogation of that law. It is clear that separate schools could not have been re-established without as a preliminary repealing the Act of 1890, of which the express purpose was to put an end to the system of denominational schools. The text of the judgment states explicitly that in order to remedy the grievance of which[22] Catholics complained it was not essential to give them back all the rights which had been taken away from them, but simply to add to the existing law provisions sufficient to protect the conscience of Catholics.

. . . But that is not all. Even supposing that the judgment of the Privy Council had declared that Catholics were entitled to the restoration of separate schools, was it possible to attain this result by a federal law? . . . Three things are indispensable in what is understood by separate schools: 1° exemption from public school taxes; 2° a distinct school organization; 3° a proportionate share in the appropriations voted by the legislature for education. These three conditions were found in the remedial order, but as your Grace knows, they were not found in the bill. The bill did not ensure a cent from the public grants for education. What was the reason for this retreat? Why after having declared in 1895 that separate were, like public schools, entitled to a grant from the provincial treasury, did the same government leave the separate schools which it pretended to re-establish without this grant? The reason given by Mr. Dickey, the Minister of Justice, was that there were very serious doubts as to the power of the federal parliament to appropriate the moneys of a provincial legislature. In other words, the Bowell government did not recognize this power as existing in the federal government.

Even assuming that the government had this nominal power, I submit to your Grace that in the state of opinion, in face of the steadily growing feeling in favour of provincial autonomy, there is not now and there never will be any government strong enough to induce parliament to lay violent hands on the treasury of a province. . . .

. . . Now, to pretend to re-establish separate schools without a public grant, would be simply a fraud.

This being the situation, I submit to your Grace that the concessions offered by the government of Manitoba will be infinitely more effective than the so-called remedial bill could ever have been, if it had become law.

As amended, the Manitoba law will give, not separate schools[23] n name—for that matter they were called public schools before 1890—but an equivalent which I believe acceptable. It will give us Catholic schools, taught by Catholic teachers, in all the districts where the number of Catholic pupils is forty in the city and twenty-five in the country, and these schools will be aided by the government like all other public schools. Further, the law as amended will provide Catholic teaching for Catholic pupils in schools where the teachers are not Catholics, at certain fixed hours.

So much for the amendments to the law. The questions of control and administration remain. I have undertaken to deal with them also, and have secured from the Manitoba government an undertaking to grant Catholics fair representation in the educational staff, the inspectors and the examining boards. With this representation, if good understanding and harmony are re-established, as I hope, and if the agreement which has been effected is carried out in the loyal and broad spirit which has been promised, the Catholics can easily reach a good understanding with the majority as to the qualification of teachers and the school curriculum.

I am ready to admit that the concessions made by the government of Manitoba do not include all that the Catholics looked for, but to seek to re-establish separate schools by federal intervention and to carry things through by main force, is a task which six years of agitation, of struggle, of bitterness, seem to me to have rendered impossible. Without dwelling on this point, I ask your Grace to consider the situation of the country, taking into account its races, its creeds, the inevitable passions, and the nobler sentiments which make provincial autonomy the foundation of our political system, and I believe that your Grace will come to the same conclusion as myself.

Religious teaching should be re-established in the schools. On this point, there is no doubt. I do not believe that it can be re-established by a federal law, and I am sure that it can be by mutual concessions, to which the provincial legislature will give its sanction.

Even admitting that it might be possible to obtain from[24] the existing parliament, or from another to be elected by the people, a law completely restoring separate schools, which would be better, such a law administered by a hostile government, or a law less perfect, but passed by the provincial legislature itself, and administered by a government which, from being hostile, had become friendly?

The proverb, dictated by popular common sense, that the worst agreement is better than the best law-suit, may be applied with as much force to political as to private affairs. It seems to me on every ground that in this case more than ever conciliation will be more effective than compulsion.

I have presented to you briefly, Monseigneur, the considerations which, as it seems to me, determine this burning question.

My colleague, M. Tarte, with the same end in view has at my request visited his Grace of St. Boniface. His mission has not been successful.

. . . I do not ask your Grace to express satisfaction with the proposed arrangement. I simply ask you to consider whether it will not be better to give the arrangement a loyal trial.

I could not ask his Grace of St. Boniface to renounce the rights which he believes are guaranteed by the constitution, but there is ground for hoping that a trial of the new régime of conciliation will give him the most complete satisfaction, reserving the right to renew the struggle, to break the truce, if these hopes prove baseless.

I ask your Grace to consider that in our system of government there are two principles perpetually in antagonism—the principle of centralization and the principle of provincial autonomy. Do you not think, as I do, that the safety of Confederation, the interests particularly of the province of Quebec, lie in the firm maintenance of provincial autonomy? Not that federal intervention should never be exercised, but only as a last resort, when every other means has been exhausted, and when all hope of conciliation and of understanding with the provincial authorities has been found vain. . . .

Accept, Monseigneur, etc.

W. L.

While some members of the episcopacy were convinced of the soundness of Mr. Laurier's contention, others continued to denounce him and all his works. The months that followed brought not calm, but rising storm. It was not surprising that to men of ultramontane views or uncompromising temper, the situation was not acceptable. Firmly persuaded of the right and duty of the Church to direct the political actions of Catholic voters and legislators, convinced that an intolerable wrong had been done their coreligionists in Manitoba and that the constitution provided a complete remedy, if only statesmen had the will to use it, surprised and angered by the disregard of their edicts shown by the electors of Quebec, they determined to use every means to reassert their authority and crush all opposition. A reign of ecclesiastical terror began, particularly in the archdiocese of Quebec, in the east of the province. Armand Tessier, editor of a Liberal journal, "Le Protecteur du Saguenay," was called to the episcopal palace of Chicoutimi, given his choice between making an abject apology for publishing articles questioning the right of the bishops to intervene in politics and having his newspaper put under the ban; he signed the apology. The leading Liberal journal of the province, "L'Electeur," of Quebec, still edited by the Ernest Pacaud of the Baie de Chaleurs episode, was not given this choice. Despite the fact that in earlier days, when Mercier was in his prime, Pacaud had received the blessing of the Pope to the third generation, "L'Electeur" was banned by bell,[26] book and candle. In a pastoral signed by Archbishop Begin of Quebec, Bishop Laflèche of Three Rivers, Bishop Gravel of Nicolet, Bishop Blais of Rimouski, and Bishop Labrecque of Chicoutimi, and read in every church in the archdiocese in the last week of December, "L'Electeur" was condemned for its denial of the episcopal right of intervention in politics, its "abusive, fallacious and insulting" comments on the action of certain bishops during the elections, its reprinting of the David pamphlet, and particularly, for an article published in November, which denied the bishops the right to decide what amount of religious instruction should be given in schools or to forbid children to attend mixed schools; all Catholics were therefore "forbidden formally and under pain of grievous error and refusal of the sacraments, to read the journal, 'L'Electeur,' to subscribe for it, to collaborate with it, to sell it, or to encourage it in any way whatsoever." Pacaud evaded the issue: that day "L'Electeur" ceased to appear, and next day "Le Soleil" was issued from the same press. Again, when Mr. L. O. David, a lifelong and intimate friend of Mr. Laurier, published a pamphlet, "The Canadian Clergy, their Mission and their Work," in which, after a solemn profession of his Catholic faith, he criticized the policy of the episcopate from the days of their opposition to the Patriotes of '37 down to their arbitrary stand on the school question, the five bishops of eastern Quebec sent it post haste to Rome, charging that it was undermining their authority at a moment when the Church had need of[27] all its power. Early in January, Mgr. Begin was able to announce in a circular letter that the offending pamphlet had been condemned by the Sacred Congregation of the Index Expurgatorius, that "each and every believer is held, under pain of grave disobedience to the Holy See, to destroy this book, or remit it to his confessor, who will do so," and that the author had, like a good Christian, submitted without reserve to this decree.

This high assertion of episcopal authority was a challenge not merely to the Liberal party but to the self-respect of individuals and the liberty of the State. How was it to be met in its political hearings? There were some Liberals who wished to bow before the storm, and await whatever crumbs of future favour the clergy might give. In counties where there were not a score of Protestants, where the parish was the community, it was not easy to face a condemnation which virtually meant ostracism, a barring of social intercourse and of public service.[3] On the other hand, there were some old Rouges who were more than ready to take up the challenge and to fight to a finish. Ex-Mayor Beaugrand of Montreal declared in his [28]journal, "La Patrie," that Quebec was the Spain of America; the episcopal attack was the beginning of a struggle to the death between the hierarchy and the government; no compromise was possible, and if "L'Electeur" was too cowardly or too poor to continue the struggle others would do so for it: "We have had our victories of June 23, as our fathers had the victories of St. Denis, St. Charles, St. Eustache, in spite of the threats of the religious authorities. I fight not for myself but for poltroons who do not dare to raise their heads."

Laurier faced the crisis squarely. He would not submit, and he would not be led into a war against the Church. Once more, as twenty years earlier, he determined to uphold the right of Catholics to be at once free citizens and faithful sons of the Church. In parliament, before the public, and at Rome itself, this was the policy he and his colleagues had already pursued, and it was the policy they determined to continue.

In parliament there was surprisingly little discussion of the issue. The government urged its followers not to taunt the losers, and to give the parties concerned in the settlement an opportunity to work it out in quiet. On occasion, however, their position was made clear beyond question. Israel Tarte put it with his usual frankness and lucidity in a debate in March, 1897:

Some of our honourable friends opposite do not seem to realize the currents of public opinion. The days are gone by when the people of Quebec could be deceived and treated as my honourable friends opposite would wish them to be[29] treated. I say that more progress in the ideas of liberty and freedom has been made in the province of Quebec in the past ten years than in any other province of the Dominion. When I started out from my parents' farm I entertained then and entertained later many of the doctrines now held by many of my Roman Catholic friends in the clergy, and it is on that account I forgive them many things. Sir, the Roman Catholic clergy of the province of Quebec is composed of good men, of moral men, there is not a more moral body of men than the priests of the province of Quebec, but I am bound to add at the same time that those men have been brought up, as it were, within closed walls, and some of them have become the unwilling tools of such men as those who sit on the opposite side of the House.

The Conservatives were quite as reluctant to make the settlement a party issue. The Conservative survivors from Quebec still demanded "justice, not a sham," and taunted the Liberal members who had signed the bishops' pledge, but the Conservatives from other provinces washed their hands of the whole question. The bishops had not delivered the goods in the last election; why worry further? Sir Charles Tupper frankly refused to pull any more episcopal chestnuts out of the fire; while denying that he had made any compact with the bishops of Quebec, he admitted he had naturally expected more support than he had received:

I am free to confess that I entirely overrated the importance of this question. . . . I find there has not been that deep importance attached to this question by a very large part of that denomination that I had previously supposed. I make this admission frankly to the House, and I cannot but feel that it is not unlikely that it will be much more difficult in the future than it was in the past . . . to induce gentlemen[30] to sacrifice their own judgment to some extent, and the feelings of their constituents to some extent, to maintain a policy which when subjected to the test of actual experience, is not found to have the importance attached to it that was previously supposed. . . . I am glad to know that the responsibility rests no longer on my shoulders, but upon those of the gentleman who is now the First Minister of the Crown.

In Quebec, the Liberals stood to their guns. They pressed to a successful conclusion their protest against the election of Dr. Marcotte in Champlain, on the ground of undue influence of curés who had declared it a mortal sin to vote for a Liberal. When in a byelection in Bonaventure in March, 1897, Mgr. Blais asked both candidates to sign a pledge to vote in the House against the Laurier-Greenway settlement or any other settlement not approved by the bishops, and to forbid their fellow-campaigners "to speak one single word in favour of the Laurier-Greenway settlement or of giving it a trial," the Conservative candidate agreed, but the Liberal candidate, Mr. J. F. Guite, flatly refused: he would like to see still better terms for his compatriots, but must use his own judgment as to the best means: "I am a Catholic, and in all questions of faith and morals I am ready to accept without restriction the decisions of the Church. In all political questions I claim the freedom enjoyed by every British subject. . . . I cannot before God and my conscience renounce the freedom of exercising my privilege as a member, to the best of my judgment." He was elected by double the previous Liberal majority,—though possibly the prospect of government railway extension[31] through the country had some influence on the result.

At the height of the crisis Mr. Laurier made his own position clear. At a banquet held by the Club National in Montreal, on December 30, a few days after "L'Electeur" had been banned, he defended the school settlement as the best practicable solution, and then, in terms which revealed the strain and tension of the hour, referred to the clerical crusade:

I have devoted my career to the realization of an idea. I have taken the work of Confederation where I found it when I entered political life, and determined to give it my life. Nothing will deter me from continuing to the end in my task of preserving at all cost our civil liberty. Nothing will prevent me from continuing my efforts to preserve that state of society conquered by our fathers at the price of so many years and so much blood. It may be that the result of my efforts will be the Tarpeian Rock, but if that be the case, I will fall without murmur or recrimination or complaint, certain that from my tomb will rise the immortal idea for which I have always fought. . . .

It is to you, my young friends, that I particularly address myself. You are at the outset of your career. Let me give you a word of good counsel. During your career you will have to suffer many things which will appear to you as supreme injustice. Let me say to you that you should never allow your religious convictions to be affected by the acts of men. Your convictions are immortal. Their foundation is eternal. Let your convictions be always calm, serene and superior to the inevitable trials of life. Show to the world that Catholicism is compatible with the exercise of liberty in its highest acceptation; show that the Catholics of the country will render to God what is God's, to Cæsar what is Cæsar's.

While defending himself resolutely from attack,[32] Laurier was strongly opposed to any counter campaign. He wanted no anti-clerical movement of the European model. With some difficulty he restrained the ardour of Mr. Beaugrand and his fellow-stalwarts, some of whom were in close touch with affairs on the Continent and were quite ready to follow Continental Liberalism in its attitude to the Church. In 1897, as in 1877, Wilfrid Laurier interpreted Liberalism otherwise. In a letter to Mr. Beaugrand he refers to the difficulties he met in making his policy prevail:

Ottawa, February 8, 1897.

My Dear Beaugrand:

. . . Let me say how much I thank you for all you say in

your letter. I cannot adequately express to you how deeply

I was touched by the interview I had with you. Between such

friends as we are, there cannot be a break, though there may

be differences. I am a Liberal, like yourself, but we do not

belong to the same school. I am a disciple of Lacordaire.

I regret that on one or two occasions I expressed my disagreement

with you in terms much too strong. Now that we have

frankly threshed the matter out, our old friendship will only

be the better for it.

I am pleased to see that the sale of "La Patrie" has gone off well,[4] and that, now that you are freed of the press of business you are going to be able to give your health all the attention that it requires. . . .

But it was not enough to take this stand before his countrymen. It had become essential to take it in Rome as well. It was necessary to appeal from those who spoke in the name of Rome to Rome itself, to ask [33]the head of their church whether Catholicism involved a loss of political independence, to avert by timely information action from Rome supporting the aggressive bishops in their stand. A steady stream of ecclesiastical visitors from Canada had presented at Rome their side of the case; the laity had not been heard. Immediately after the general elections, therefore, a group of Quebec Liberals determined to state their case. Abbé Proulx of St. Lin des Laurentides, who had supported the Liberals on the school issue, and Chevalier Drolet, who had been a member of the crusader band of Zouaves who had rallied to the defence of the papacy nearly thirty years before, were despatched to Rome. A semi-private letter from Mr. Laurier to M. L'Abbé Proulx provided his credentials:

My dear M. Proulx: The attitude taken during the recent elections by Mgr. Laflèche and some other members of the episcopate, was, in my opinion, a great mistake. It seems to me certain that this violent intervention of the ecclesiastical authorities in the electoral arena cannot but have harmful consequences for the position that Catholics hold in the Confederation, and that it is equally likely to trouble the consciences of the faithful.

It may seem unseemly on my part to speak thus. I persist, however, in believing that the attitude which my political friends and I have taken in the question which was then submitted to the electors was much more in conformity with the ideas frequently expressed by his Holiness Leo XIII than the attitude of Mgr. Laflèche and of those who acted with him.

It is not, I think, presumptuous to believe that if the[34] question is submitted to the pontifical authorities at Rome, we may expect a statement of doctrine which would have the effect of bringing regrettable abuses to an end, maintaining peace and harmony in our country and reassuring the consciences of Catholics.

As you are about to sail for Rome, you will render a great service to the Catholics of this country who unfortunately have incurred the disfavour of certain members of the episcopate, because of their political opinions and for no other reason, if you would state their case and represent to the pontifical authorities that all they seek in this country is to exercise their duties as citizens in accord with the recognized principles of the British Constitution, principles recognized equally by his Holiness Leo XIII.

In a more personal letter of the same date Mr. Laurier gave further suggestions for guidance:

I am sending you herewith a private letter not intended for publicity, but which may however be shown as a credential. Mr. Drolet will leave shortly for Rome. My colleagues in the House of Commons are sending him as their advocate and interpreter to state their case officially before the pontifical authorities. I would like you to keep in touch with him, in order to inform him as to all useful steps that should be taken to attain the end in view.

In a short time I shall send you a memorandum relative to the settlement of the school question, but the first thing to do is to make the pontifical authorities understand that we are Catholics and that we wish to remain Catholics but that in a constitutional country such as ours the attitude taken by Mgr. Laflèche and certain other members of the episcopate, if approved at Rome, would place us in a position of inferiority such that a Catholic could never become prime minister nor even form part of a government like the Canadian, in which[35] Protestants are necessarily in a majority, since the Protestants are in a majority in the country.

I must repeat to you also what I have said already, that while disapproving the conduct of members of the episcopacy, to which I have just referred, it is not the intention of any of us to expose them to the slightest humiliation. If you consider it advisable that a delegate should be appointed for Canada, you will please inform me. I need not say to you that the selection of such a delegate would be of very great importance.

Accept my best wishes for your voyage.

The two envoys made their way to Rome, finding "half ecclesiastical Canada there before us or on the way." In Rome, progress was slow. The affairs of all the ends of the earth met there; rules of etiquette and audience were stiff; there were so many personages to see. "The impossibility of making rapid progress," writes Mr. Drolet, "often the necessity of making no progress at all, with the Congregations, with this Black monde, jealous, oh so jealous, meddling, old, old above all." In moments of despair he was prepared to believe Zola's "Rome" not wholly false. It was not easy to convince Rome that Bishops were in error and laymen right. The bishops had long had the ear of Cardinal and Congregation. Had not the Queen in Council commanded that separate schools be restored? Had not Protestant Tupper tried to restore them and had not Catholic Laurier resisted? Was not this Laurier a bad Catholic, a Free Mason?[5] And perhaps the [36]good Mr. Drolet was not the most tactful of envoys, unduly suspicious and belligerent, laying emphasis on his long dossier containing two hundred charges of intimidation against this bishop and that curé, rather than on the danger of the recoil to the Church itself. "The old gentleman is rather a light weight," wrote a critic, "a kind of Monsieur Tartaran, who got on the wrong track from the first and among the wrong set."

[37]He fared somewhat better when he turned from Cardinal Ledochowski, head of the Propaganda, and thus the champion of the bishops under his charge, to the Secretary of State, Cardinal Rampolla.

Whatever the reason, progress was slow. It became necessary to take more direct and more effective steps. It was decided to make a formal and collective statement of the case, to send other representatives to Rome, and to press for the appointment of an apostolic delegate. These conclusions were not reached without debate. Tarte opposed Laurier's suggestion of a joint petition to his Holiness, as likely to be twisted or misconstrued by Protestants, but when Laurier made it clear that it was not the political question, not the settlement of the school issue, but the conflict within the Catholic Church in Canada that the Pope was to be asked to consider, he became an ardent supporter of the plan. Forty-five members of the Commons and the Senate, Wilfrid Laurier's name leading, signed a petition and protest.[6] There was also some question as [39] to the coming of a papal legate. True, the visit of Cardinal Satolli to the United States in 1892, and the visit of Mgr. Conroy to Canada in 1876 had brought peace and liberty, but much depended on the man. An Ontario bishop foresaw Protestant denunciations of Papal interference, and feared "that a delegate sent from Rome or France who, being prepossessed, as all Continental ecclesiastics are, with the idea that Liberalism in politics is synonymous with infidelity, could not grasp the idea that Liberalism here bore no relation to what is known by that name on the Continent." Yet the risk seemed worth running. The new envoys were Charles Fitzpatrick and Charles Russell, son of Lord Russell of Killowen, whose family spent the winters in Rome. Fortified by a strong statement from Edward Blake, counsel for the minority, that the Judicial Committee could not, and did not, command the restoration of the schools as they were before 1890, and that the terms of the Laurier-Greenway settlement were more advantageous to the Catholic minority than any remedial bill which it was in the power of the parliament of Canada to force on the province of Manitoba, and with letters from Cardinal Vaughan and the Duke of Norfolk, the envoys went to Rome. At once progress was rapid. Mr. Russell's wit and knowledge of Anglo-Roman politics opened many doors. Mr. Fitzpatrick's piety was "the wonder and the awe of Rome." With the Secretary of State, Cardinal Rampolla, with all the other cardinals who were likely to be consulted, Cardinals Vannutelli, Vicenti, Jacobini, Ferratta, [40] Ledochowski, Gotti, and Mazella,—of whom only Mgr. Ledochowski refused a fair hearing, all the others impressing the visitors as "men of strong intelligence and judgment who were anxious to learn the truth,"—with Mgr. Merry del Val, the Pope's companion and attendant, and finally in an audience with His Holiness himself, the case was urged. It was necessary to make it clear not merely that the judgment of the Privy Council had no mandatory effect, but that Canada was not, as seemed to be assumed in Rome, a predominantly Catholic country, and that not all the bishops, but only six out of twenty-nine had committed themselves to the war against the Liberal party. The promise to make full inquiry through a special commission of cardinals was readily given. The appointment of an apostolic delegate, Mgr. Merry del Val, followed a few weeks later.

Mgr. Raphael Merry del Val was then only thirty-two, but he had already made his mark in Europe. In the household of his father, a Spanish nobleman of Irish descent who was ambassador in turn to London, to Brussels and to Rome; in schools in England and in Brussels; in the Papal Court, where he soon became confidential chamberlain, Mgr. Merry del Val proved his ability and his judgment. His striking presence,—"the most truly prince-like man, I ever met," Mr. Laurier afterward termed him, his searching but kindly eye, his polished but somewhat reserved address, his mastery of European tongues, his shrewdness, thoroughness, and, above all, the complete confidence[41] he inspired, made him a diplomat predestined to success. He arrived in Canada late in March; in the next few months he met the bishops and many of the clergy of Quebec and Ontario, and leading Catholic and Protestant laymen. It did not take long for him to realize how dangerous a policy Mgr. Laflèche and his friends had been pursuing. Archbishop Walsh and the majority of the Ontario bishops strongly confirmed his reading of the situation. Not least, the instant friendship and confidence which developed between Mgr. Merry del Val and Mr. Laurier contributed to a firm understanding. He issued no mandement, made no public rebuke, but gradually agitation ceased, and Mgr. Merry del Val returned to Rome.

After hearing the apostolic delegate's report, and after consulting further with members of the Canadian episcopacy, including the new Archbishop of Montreal, Mgr. Paul Bruchesi, the Pope issued an encyclical, given at Rome on December 8, 1897, and read in Canadian pulpits a month later. The encyclical noted with regret the obstacles which had been placed in the way of the Church's efforts in a country which owed to it the first glimpse of Christianity and civilization, and emphasized the importance of morals in education, and the necessity of grounding morals in religion. The bishops had therefore been right in protesting against the Manitoba law, which struck a blow at Catholic education; the laity should have sunk differences of party and stood united for justice. True, something had recently been done to alleviate the grievances; no[42] doubt these efforts had been inspired by laudable intentions and a love of equity, but the fact remained that "the law which has been enacted for the purpose of reparation is defective, imperfect, insufficient." The concessions stopped far short of justice; they might not be carried out effectively, when local circumstances changed. Complete justice must be sought. However, there was room for difference of opinion as to the best tactics to follow; "let no one therefore lose sight of the rules of moderation, of meekness and of brotherly charity." Meanwhile, "until it shall be granted them to obtain the full triumph of all their claims, let them not refuse partial satisfaction. Wherever the law or the situation or the friendly disposition of individuals offer them some means of lessening the evil, and of better averting its dangers, it is altogether becoming and useful that they make use of these means and draw from them the utmost possible advantage." The greatest care should be taken to improve the quality of teachers and the scope of the work of the schools; the Catholic schools should rival the most flourishing in methods and efficiency: "from the standpoint of intellectual culture and the progress of civilization there is nothing but what is great and noble in the plan conceived by the Canadian provinces of developing public instruction, of raising its standards constantly, and making it something higher and ever more perfect; there is no kind of study, no advance in human knowledge, which cannot be made to harmonize with Catholic doctrine."[43]

In this moderate and enlightened utterance, both sections of opinion within the Church in Canada found ground for satisfaction, but the general effect was distinctly in support of the moderates' position. The Laurier-Greenway settlement had been pronounced imperfect and inadequate as a final settlement, but its acceptance as an instalment of justice had been commended, moderation and a recognition of the good-will of its framers enjoined, and emphasis laid on the quality of instruction to be given in the schools. Nothing further could have been expected in a public statement, and Mr. Laurier and his Quebec friends had not desired more. The school question was by no means yet ended, but the ecclesiastical war was halted, and the political tension eased. Once again, as a score of years before, the firmness and moderation of Wilfrid Laurier and the Catholic Liberals of Quebec, and the sagacity and fairness of the highest authorities in the Church, had averted a struggle which would have involved both Church and country in difficulty and disaster.

The failure of the crusade was made evident when in the spring of 1897, the time came for the provincial elections in Quebec. The Conservative government of Hon. E. J. Flynn, who had become premier when Mr. Taillon had entered the Tupper administration, absolutely declined to make the school question an issue in the local contest. The prestige of Laurier's name and the rout of the Conservatives in the federal contest gave an overwhelming victory to the Liberal leader,[44] Felix Gabriel Marchand, a man lacking the oratorical gifts and the personal magnetism of many of his predecessors but shrewd and solid, trusted of all men, and firmly progressive in his policies. When, however, Mr. Marchand endeavoured to put educational reform in the forefront of his legislative programme, and to reverse the policy adopted twenty years before, which had taken control of the schools from a government department and entrusted it wholly to denominational committees, Catholic and Protestant, he found himself blocked. The truce was held to bind both parties. The Archbishop of Montreal, Mgr. Paul Bruchesi, who kept in close touch with Wilfrid Laurier, soon proved that sunny ways and personal pressure would go further than the storms and the thunderbolts of the doughty old warrior of Three Rivers.

The settlement of the Manitoba school controversy made it possible to concentrate attention upon policies of economic development. For years the country had marked time. The depression which had set in with the "nineties" had not yet passed. The prices of farm products were low, farms hard to sell and burdened with mortgages. Railways, banks, wholesale houses, retailers had to scratch hard for custom. Factories stimulated by the N. P. found the home market too small and sought remedy in combines and selling agreements. Foreign trade advanced slowly and uncertainly. Few immigrants came and fewer remained; the exodus of the native-born to the United States bled the[45] country white. Homestead entries in the West had fallen to four thousand a year in the early "nineties," and to eighteen hundred in 1896; in that year only five hundred and seventy Canadians had sufficient faith in their own country to seek a Western homestead. West of Lake Superior there were only some three hundred thousand people, one-third of them Indians. "The trails from Manitoba to the States," declared a Western Conservative newspaper, "were worn bare and brown by the wagon wheels of departing settlers."

The causes of this economic stagnation were not wholly Canadian. World-wide factors had played a part. World peace and rapid railway-building had opened vast areas of new lands to settlement,—the western United States, Argentina, Australia, Russia,—and had flung their products on a falling market. Canada's severe and testing climate, exaggerated in foreign repute, and perhaps her subordinate colonial status, had played a part in deterring settlers. But there were other causes more readily removed: a protective tariff which sought to isolate and make self-sufficient a population too sparse and scattered for the experiment; racial and religious bickerings (for which both parties had a share of responsibility) draining and distracting energy; and a government weak and divided in cabinet council and permeated with dry-rot in the general administration.

The turn of the tide after 1896 was of course not due solely to the change of government. World-wide forces played a part in revival as in depression. The[46] filling up of other new lands, the growth of urban as against rural population, the rapid increase in the world's gold supply, raised prices of all goods and particularly of farm products. Within Canada, again, forces beyond the government's control made for betterment. Most notable were the development of the gold-copper and silver-lead ores of Southern British Columbia (the prospector, it is true, being helped by the building of the Canadian Pacific), and particularly the discovery of fabulously rich placer-mines in the Klondike in 1896 and the stampede from all corners of the world which followed in 1897 and 1898. Perhaps less wealth was taken out of the ground than was put in, but these discoveries at least primed the pump of prosperity, and arrested the world's attention long enough to make evident the more enduring wealth that lay beyond.

Yet the new government were not merely "flies on the wheel," as Sir Richard Cartwright had once rashly rated the Mackenzie cabinet during the depression of the seventies. They had confidence in Canada and in themselves, energy, constructive vision. The policies they developed in the next few years were real and indispensable factors in the new prosperity. They did not create the opportunity; they did seize it when it offered. The immigration policy, the land policy, the railway policy, the tariff and fiscal policy of the Laurier administration were essential elements in making Canada what Mr. Laurier was soon to term it, in a quota[47]tion now as hackneyed as "Hamlet,"—"the country of the twentieth century."

The land and immigration policy of the administration was developed by its youngest and sole Western member, Clifford Sifton. He had entered the government as Minister of the Interior, in November, 1896, as soon as agreement had been reached between Ottawa and Winnipeg on the school question, securing election for Brandon by acclamation. He knew the West; he was ambitious for himself and for his country; his shrewd insight, his administrative capacity, his power of quick decision, were qualities rare at Ottawa. In dealing with the public lands of the prairie provinces, the chief action taken was to end at once, as Liberal policy had long demanded, the lavish grants of land to railways. Before 1896 some fifty-six million acres had been voted and some thirty-two million acres earned as railway subsidy; after 1896, not an acre was voted. Homestead regulations were eased and simplified. Then a campaign for settlers began, unparalleled in Canada or elsewhere. From Continental Europe the Doukhobor and the Ruthenian were brought or welcomed, filling Western wastes but creating difficult problems of social or national harmony. From the United States came the immigrants most immediately helpful in themselves, farmers as most were, with no little capital, skilled in the ways of Western land, and most effective in advertising to the rest of the world the fact that Canada had now more to offer the settler than[48] any other country. Advertisements in six thousand weekly newspapers in the United States, agents and sub-agents stationed in every likely centre, exhibits at autumn fairs and free excursions for pressmen and farmer delegates, ready aid in land-seeking and home-shifting, soon set going a migration that rejoiced Canada, puzzled the States and aroused Europe. From seven hundred in 1897 the settlers from the South rose to fifteen thousand in 1900,—and one hundred thousand in 1911. Then Mr. Sifton turned to the United Kingdom, the schools, the press, the patriots who wanted Britons kept within the Empire; the British tide mounted more slowly, but soon surpassed the Continental and American movements,—thirty thousand in 1904, a hundred and twenty thousand in 1911. The exodus to the more dazzling city opportunities of the United States, the return to Europe of the men who had not found gold lying in the streets of their New Jerusalem, continued, but were far outbalanced by the incoming tide. Homestead entries leaped to seven thousand eight hundred by 1900, twenty-two thousand by 1902, and forty-one thousand by 1906.

In Canada, it had become accepted doctrine that the State should not merely aid settlement, but should aid in developing the means of communication. No great new railway was built in these early years; the country was still growing up to the Canadian Pacific. Three minor and supplementary projects were given aid. In the East the government, in 1897, sought to extend the Intercolonial, by lease and purchase, from the wayside[49] village of Pointe Levi to the natural terminus at Montreal; the details of Mr. Blair's plan were open to criticism, but some such policy was an obvious business necessity. In the West, the discovery of coal, copper, gold, silver, and lead in southern British Columbia and Alberta, called for railway service, and none the less so when "Jim" Hill thrust a spur of the Great Northern up into the boundary country. General opinion favoured an independent road, but in 1897 the government concluded the most feasible policy was to seek an extension of the Canadian Pacific. A subsidy of eleven thousand dollars a mile was voted to its Crow's Nest Pass branch, from Lethbridge to Nelson; in return, freight rates on the main line were cut substantially, and one-fifth of the coal lands granted improvidently by the British Columbia government were transferred to the Dominion. Western hostility to the Canadian Pacific, Eastern suspicion of Toronto capitalists interested alike in Crow's Nest coal and in the Toronto "Globe," the foremost advocate of extension, led to wide criticism, but the bargain was carried through. A third project, brought forward in 1898 for the building of a railway from the Stikine River to Teslin Lake, and thus giving access to the Klondike through Canadian territory instead of through the Alaskan panhandle, involved a grant of twenty-five thousand acres of Yukon lands per mile to the enterprising contracting firm of Mackenzie and Mann, now first coming into public fame. In the light of Eldorado visions, the land grant seemed extravagant, and the Senate felt sufficient public backing to[50] throw out the government's measure. The completion of the St. Lawrence canal system to a fourteen-foot level was less controversial, and the abolition of all canal tolls was welcomed on all sides, not least in the Maritime provinces where it furnished a precedent for demands for low rates on government railways. The Post-Office Department, hitherto inefficient and a source of large deficits, was transformed under the management of William Mulock, one of the strongest administrators in the cabinet; a great improvement in service and a reduction of postal rates by one-third were justified by increased business and steadily rising surpluses.

As regards state aid to production, little had been done directly for the fisherman, the lumberman or the miner. Fishing-grounds had been conserved by close seasons, restocking, protection against outside poachers; now, instruction in curing and packing, and later cold-storage and fast-shipping facilities were added. The lumberman and the miner had shared the benefits of railway facilities and the two-edged gift of tariff protection; now fresh efforts were made to open foreign markets and to lessen tariff burdens on mine and mill machinery. The farmer had been aided by experimental farms; now, under Sydney Fisher's direction, the work of experiment and instruction was greatly widened, and, with the co-operation of the Saunders, James Robertson and J. A. Ruddick, the Eastern farmer was aided in that shift from wheat and barley to cheese and bacon which has transformed Canadian agriculture.[51]

One great field of state aid to production remained, and that the most controversial. The use of the tariff to stimulate and protect industry, particularly manufacturing, had been the most distinctive of Conservative policies for nearly twenty years. What was the Liberal policy to be? In the Ottawa convention in 1893, in repeated speeches, notably during Mr. Laurier's Western tour in 1894, and in open letters exchanged on the eve of the general election between Mr. Laurier and a Toronto manufacturer, George H. Bertram,—a grandson of his old friend of New Glasgow days, John Murray,—the policy of the Liberals had been declared. They denounced protection, urged the reduction of the tariff to bear lightly on the necessaries of life and "to promote freer trade with the whole world, particularly with Great Britain and the United States," reiterated the demand for "a fair and liberal reciprocity treaty with the United States," and set as their goal "a tariff for revenue only." There was a distinct revival of low-tariff sentiment in the "nineties," following the failure of protection to protect, and on this current even an "incidental protectionist" like Mr. Laurier was once swept on to prophesy that "free trade as they have it in England" would be Canada's ultimate goal, while Mr. Davies denounced protection as bondage, robbery, a system accursed of God and man. Yet Mr. Laurier made it plain, particularly in the Bertram correspondence, that change must be gradual; there would be no tariff revolution; one advantage of a tariff primarily for revenue, would be its stability.[52]

The first step of the new administration created confidence. Instead of meeting protected manufacturers secretly in "Red Parlours," the government appointed a committee—Sir Richard Cartwright, Mr. Fielding, and Mr. Paterson—to hear in public all who had views to present. Sittings were held in the leading centres; not many others but manufacturers gave evidence, but their demands were made in the open.

Mr. Fielding brought down his first budget in April, 1897, in a speech which revealed his power of lucid statement and readiness in debate. It was a modest budget, as budgets go nowadays. In the first twenty years of Confederation, the ordinary expenditure had grown threefold, from the original thirteen millions, and then for ten years had stood stationary. Mr. Fielding forecast for 1897-98 an ordinary expenditure of $39,000,000, and a total outlay of $45,000,000.[7] To raise this amount, it was still customary to rely almost wholly on tariff and excise duties. Mr. Fielding stiffened the excise duties on spirits and tobacco, but the main interest lay in the customs changes. The tariff revision was substantial and comprehensive. Important additions were made to the free list, notably corn, fence wire, binder twine, cream separators, mining machinery; reductions were made in sugar, flour, farm implements, and coal-oil. The schedules were simplified and specific duties largely changed to ad valorem. Power was taken to abolish duties on goods [53]produced by trusts or combines. The duties on iron and steel were lowered, but in compensation the bounties on pig-iron, puddled iron bars and steel billets were increased, and made to apply to iron manufactured in Canada from foreign ore. Most important, the principle of a maximum and minimum tariff, with special reference to Great Britain, was introduced.

The first Fielding budget was a masterly achievement. It was a careful and informed endeavour to harmonize and reduce the tariff. It was not wholly consistent: the increase of the iron and steel bounties and the retention of the duty on coal, in face of Mr. Laurier's declaration after the election that raw materials such as coal and iron would be free, revealed the pressure of Nova Scotia interests. It left the tariff still protectionist; and while Sir Charles Tupper declared that the tariff would ruin and paralyze the industries of the country, and the columns of the Montreal "Gazette" were filled with announcements from manufacturers that their mills would be forced to close, Mr. Foster insisted that "the Liberal party has embalmed the principle of protection in the tariff" and that "there is to-day, in this parliament, as between the two sides, practically no difference upon the expediency of the principle of protection as the guiding principle of our fiscal system." John Ross Robertson, a sturdy independent Conservative who had broken from his party on the school question, but was a confirmed protectionist, gave a middle view when he declared that while the Liberals might be considered half-seas-over on the[54] way to protection, he feared their gradual attack as the most dangerous strategy and could not fully trust them even if they did steal the Opposition's clothes: "the Opposition is the mother of protection and loves the policy for its own sake; the government is a sort of nurse that takes protection and suckles it in order to earn a living for its party." Yet the weight of contemporary opinion and later experience have stamped the Fielding tariff as a sound and moderate revision.